Design and Validation of a Brain-Controlled Hip Exoskeleton for Assisted Gait Rehabilitation Training

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Structural Design and Modeling Analysis

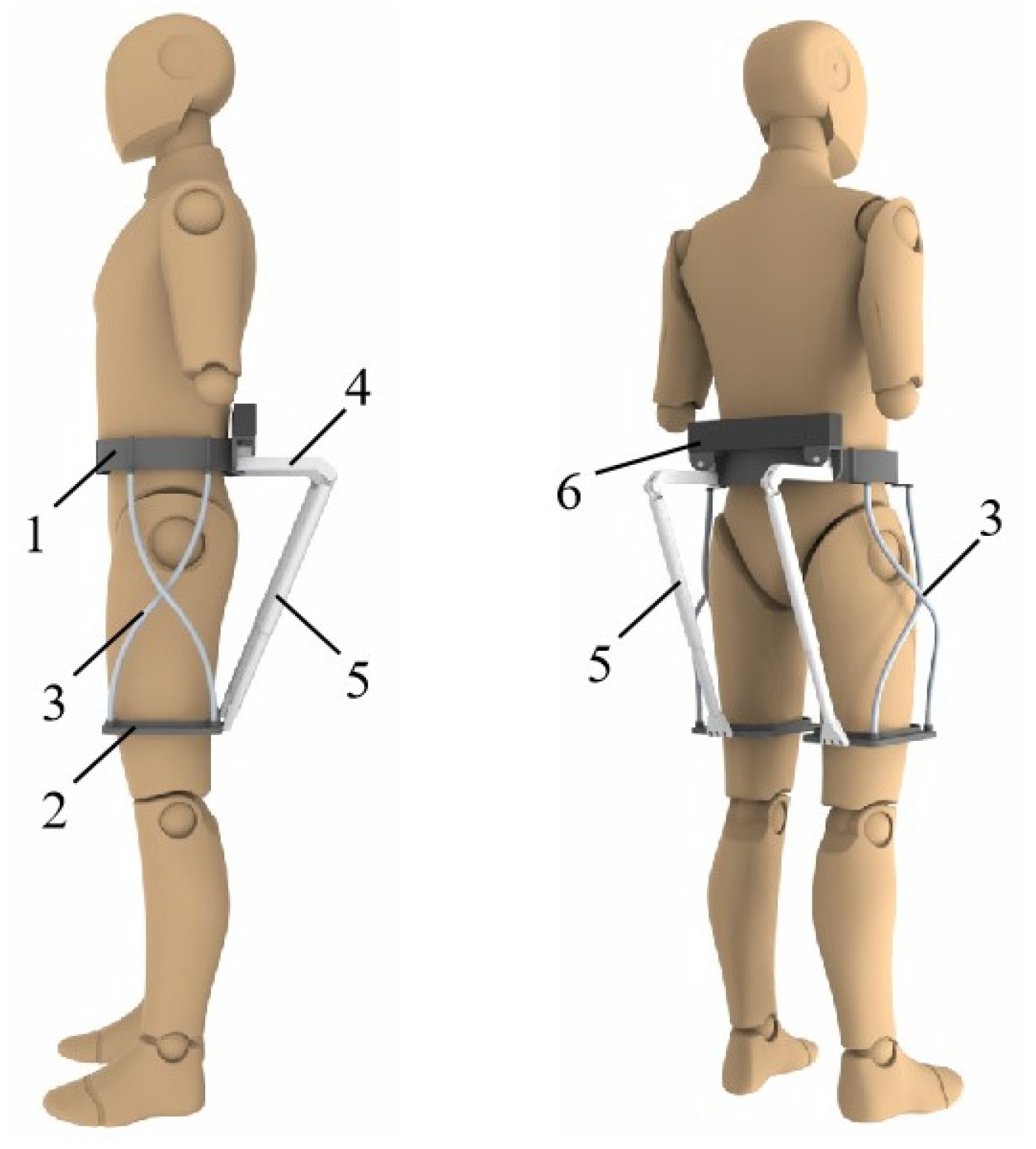

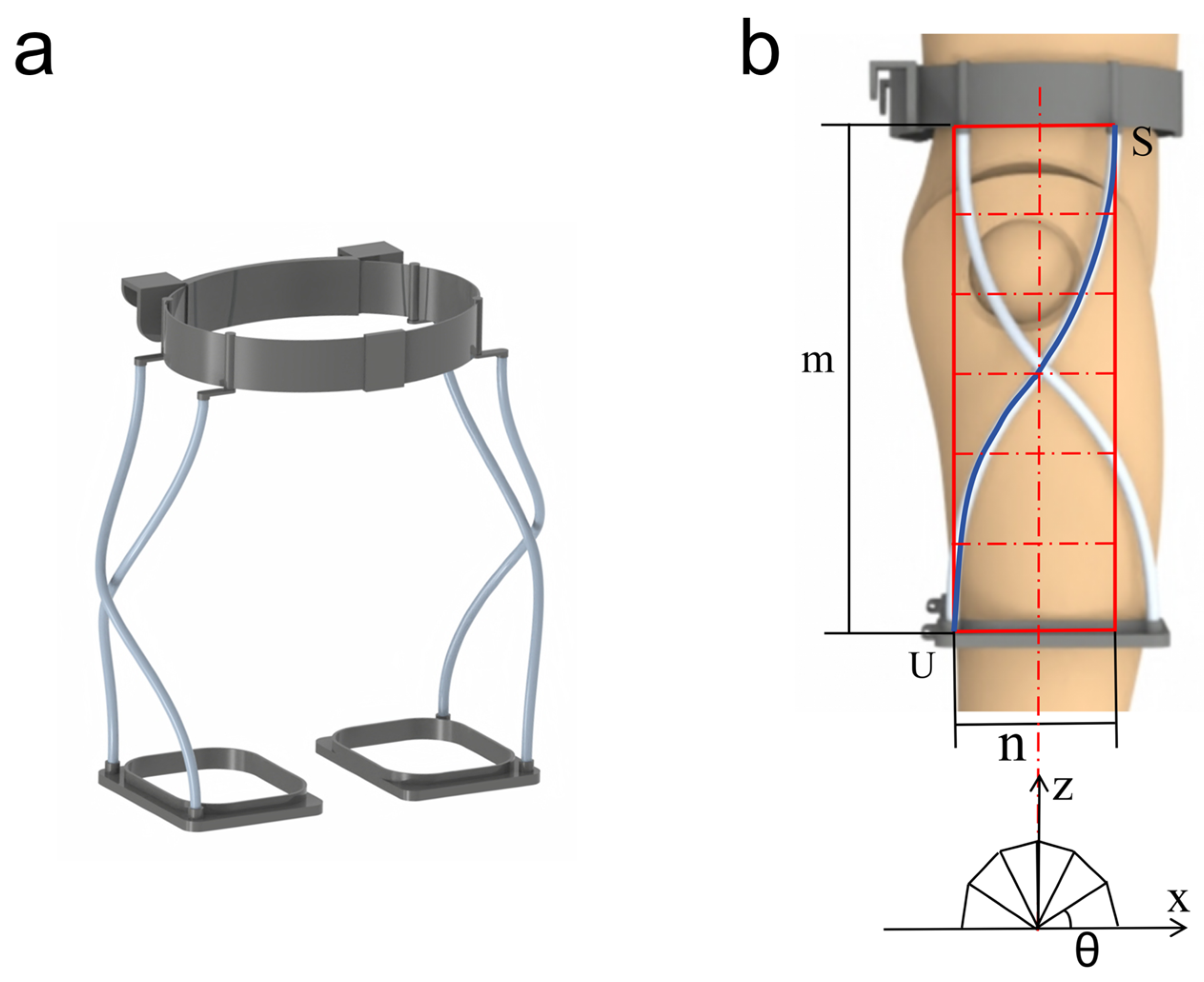

2.1. Exoskeletal Structure

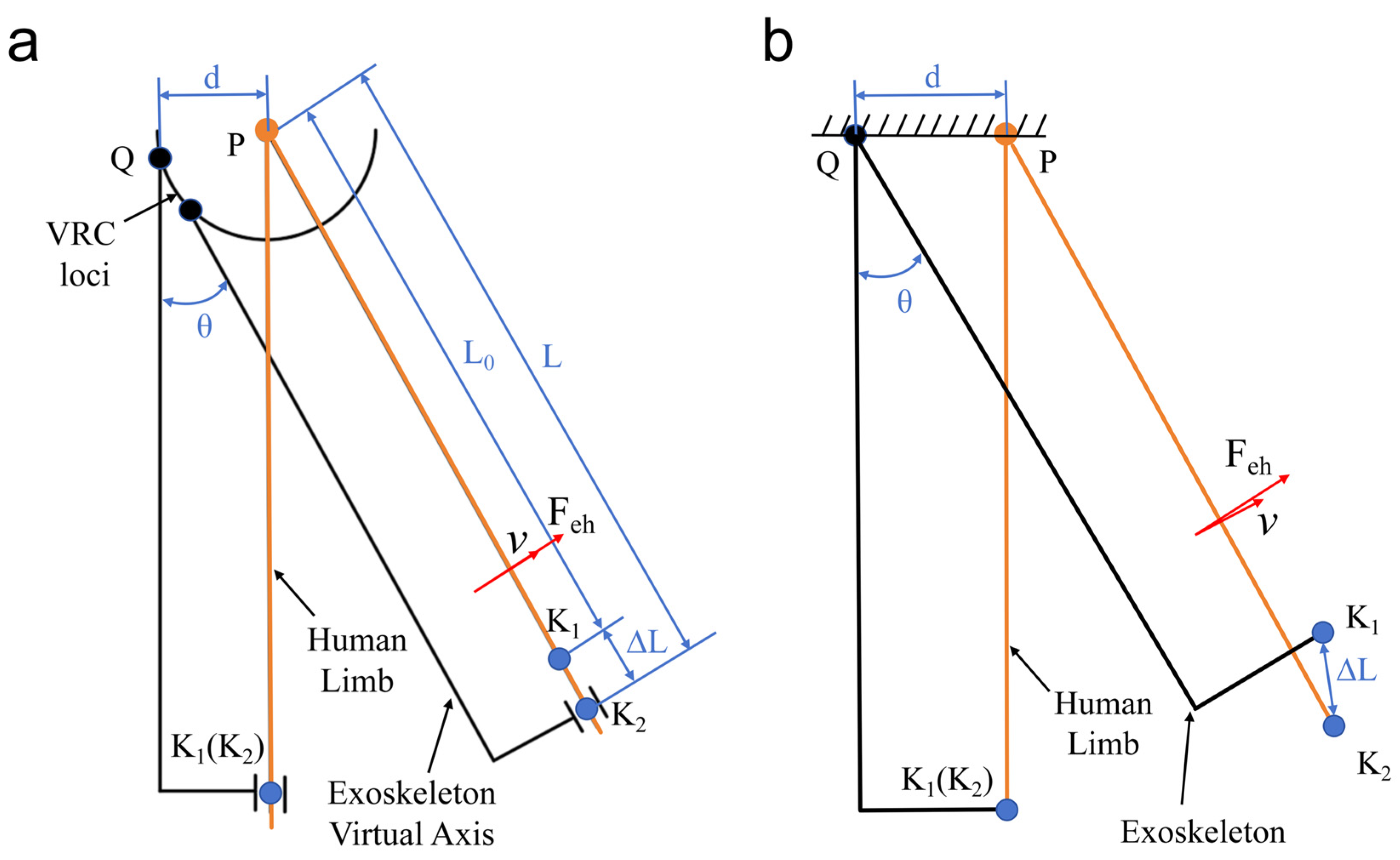

2.2. Kinematic Analysis and Quantitative Misalignment

2.3. Human–Machine Interaction

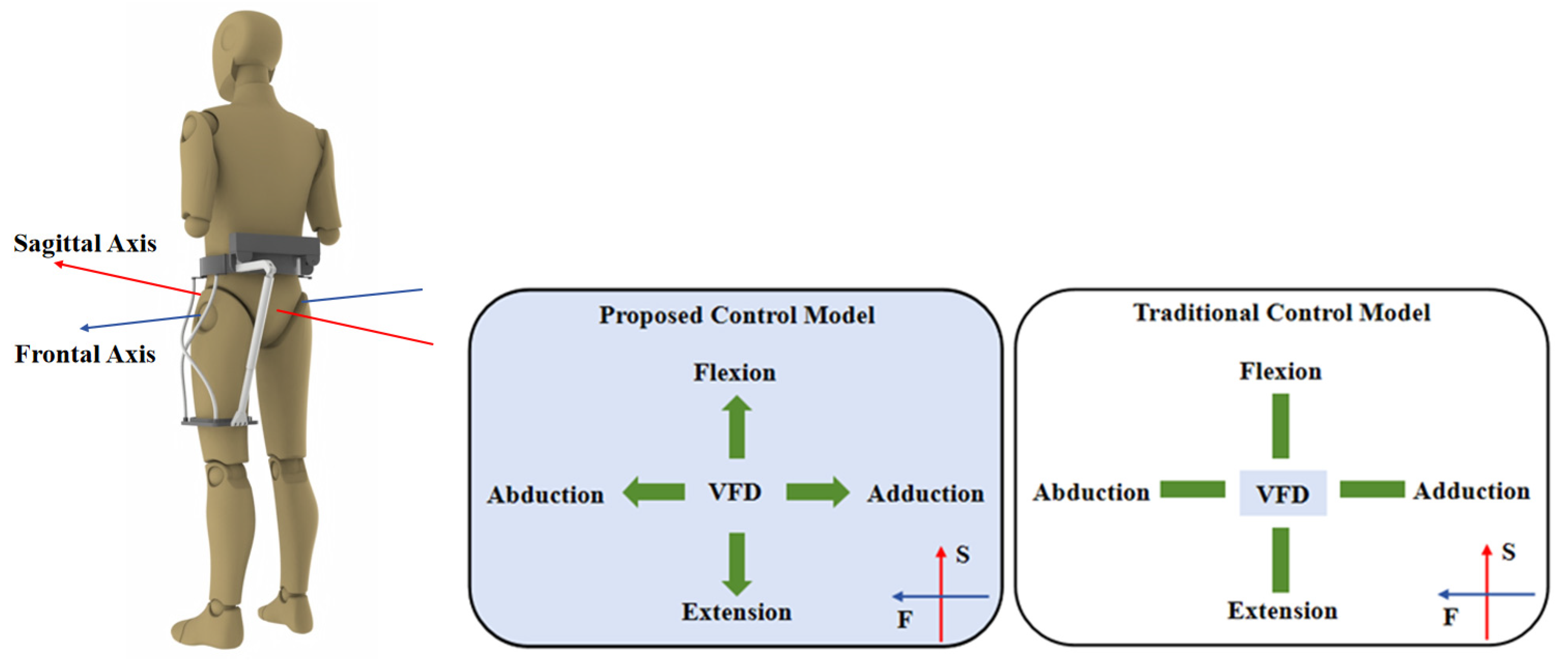

3. Design of a Brain-Controlled Hip Exoskeleton System

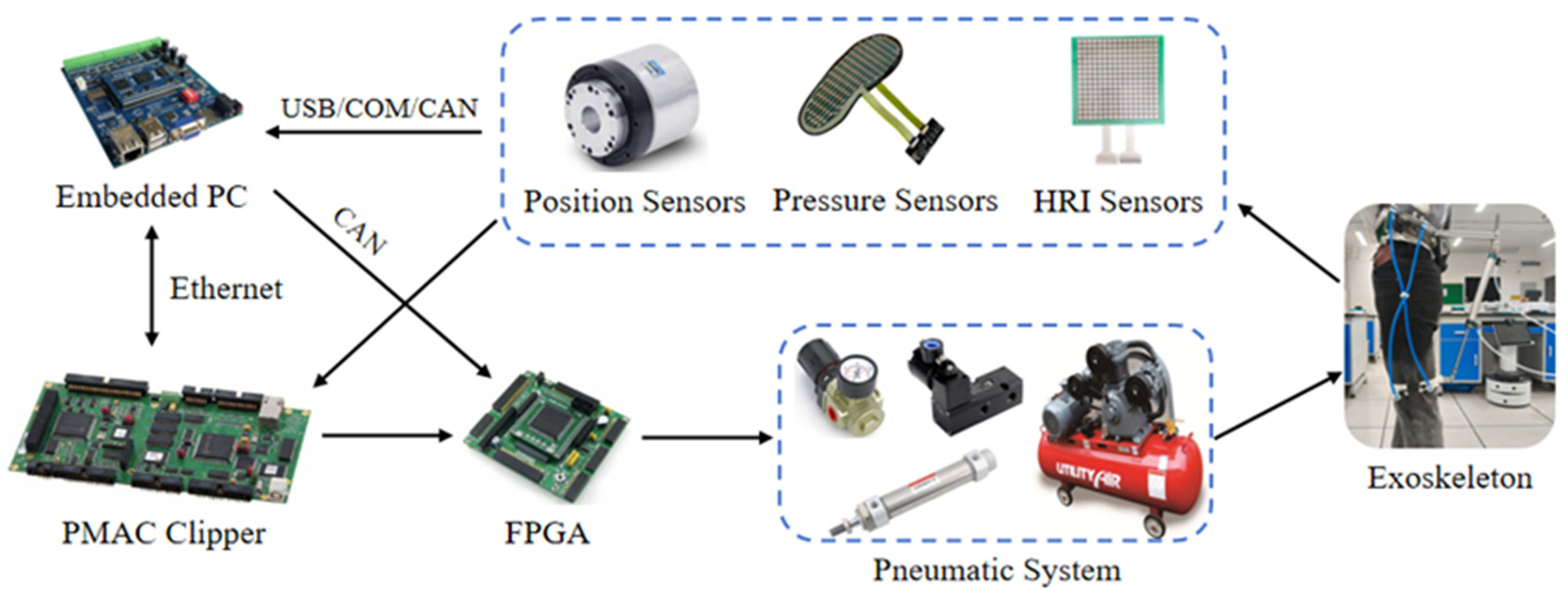

3.1. System Description

3.2. AR-VS Paradigm Module

3.3. BMI Module

3.4. Robot Module

4. Experiment and Results

4.1. Experimental Equipment

4.2. Experimental Steps

4.3. Data Processing

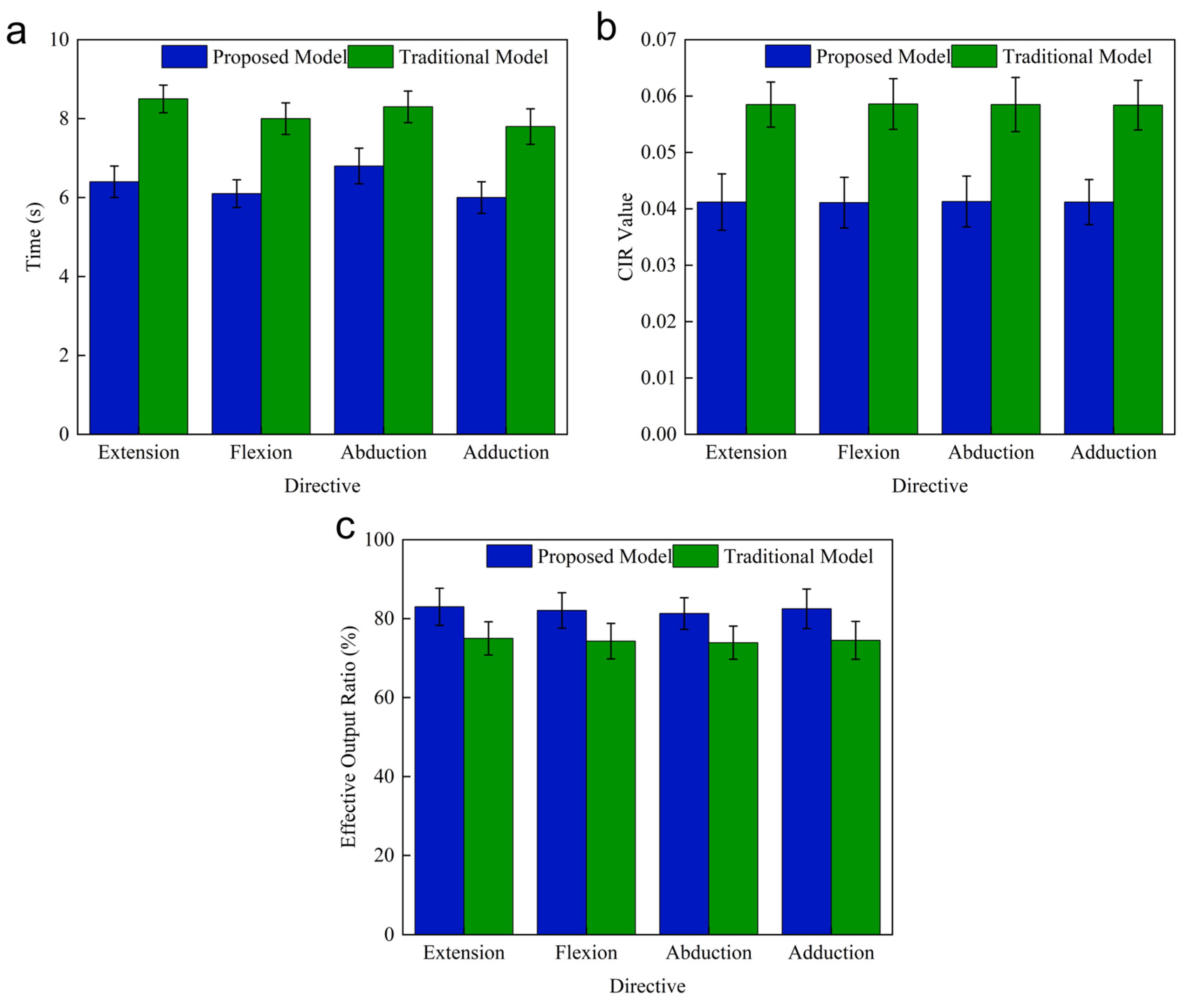

4.4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGovern, E.; Pringsheim, T.; Medina, A.; Cosentino, C.; Shalash, A.; Sardar, Z.; Fung, V.S.; Kurian, M.A.; Roze, E.; Pediatrics, M.T.F.O. Transitional care for young people with neurological disorders: A scoping review with a focus on patients with movement disorders. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Fang, Y.; Yao, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, L.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y. Burden of common neurologic diseases in Asian countries, 1990–2019: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Neurology 2023, 100, e2141–e2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, A.S.; Mogharbel, G.H.; Aljohani, S.A.; Surrati, A.M.; Surrati, A. Predictive factors and interventional modalities of post-stroke motor recovery: An overview. Cureus 2023, 15, e35971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wu, B.; Liu, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Anderson, C.S.; Sandercock, P.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Cui, L. Stroke in China: Advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Dai, A.; Feng, S.; Zhu, T.; Liu, M.; Shi, J.; Wang, D. Immediate neural effects of acupuncture manipulation time for stroke with motor dysfunction: A fMRI pilot study. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1297149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, L.; Li, R.; Wang, Z.; Hou, X.; Gu, W.; Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Xu, D. Stroke increases the risk of hip fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 3149–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, A.; Lawson, B.; Goldfarb, M. A controller for guiding leg movement during overground walking with a lower limb exoskeleton. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 34, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Su, C.-Y. Human-in-the-loop control of a wearable lower limb exoskeleton for stable dynamic walking. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 26, 2700–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Ji, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, W. A wearable lower limb exoskeleton: Reducing the energy cost of human movement. Micromachines 2022, 13, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Rajabi, N.; Taleb, F.; Yang, Q.; Kragic, D.; Li, Z. Shaping high-performance wearable robots for human motor and sensory reconstruction and enhancement. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, S.; Qu, B.; Bai, S. Design and experimental verification of a hip exoskeleton based on human–machine dynamics for walking assistance. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2022, 53, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.-T.; Kang, I.; Joh, J.; Kim, P.; Herrin, K.R.; Kesar, T.M.; Sawicki, G.S.; Young, A.J. Effects of bilateral assistance for hemiparetic gait post-stroke using a powered hip exoskeleton. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 51, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Ning, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, M. Design and validation of a lightweight hip exoskeleton driven by series elastic actuator with two-motor variable speed transmission. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 2456–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Ning, C.; Zeng, B. Development and adaptive assistance control of the robotic hip exoskeleton to improve gait symmetry and restore normal gait. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 21, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessler-Etten, J.; Schaake, L.; Prange-Lasonder, G.B.; Buurke, J.H. Assessing effects of exoskeleton misalignment on knee joint load during swing using an instrumented leg simulator. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; He, Y.; Yang, J.; Cao, W.; Wu, X. Design and analysis of a novel 12-DOF self-balancing lower extremity exoskeleton for walking assistance. Mech. Mach. Theory 2022, 167, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh Gonabadi, A.; Antonellis, P.; Dzewaltowski, A.C.; Myers, S.A.; Pipinos, I.I.; Malcolm, P. Design and evaluation of a bilateral semi-rigid exoskeleton to assist hip motion. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J. Reconfigurable exomuscle system employing parameter tuning to assist hip flexion or ankle plantarflexion. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Chen, C.; Shi, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X. A time division multiplexing inspired lightweight soft exoskeleton for hip and ankle joint assistance. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Jackson, T.M.; Natividad, R.F.; Lim, D.Y.L.; Hernandez-Barraza, L.; Ambrose, J.W.; Yeow, R.C.-H. A wearable soft robotic exoskeleton for hip flexion rehabilitation. Front. Robot. AI 2022, 9, 835237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.D.; Cooper, M.; Eckert-Erdheim, A.; Orzel, D.; Walsh, C.J. A soft exosuit assisting hip abduction for knee adduction moment reduction during walking. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 7439–7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Guo, M.; Hui, C.; Li, S.; Ji, X.; Yang, Y.; Luo, X.; Xia, D. Learning-based repetitive control of a bowden-cable-actuated exoskeleton with frictional hysteresis. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Dong, D.; Chen, X.; Bai, L. From sensing to control of lower limb exoskeleton: A systematic review. Annu. Rev. Control. 2022, 53, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhou, P.; Wang, S.; Chang, H. Tracking control with active and passive training cycle switching for rehabilitation training walker. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 185, 104887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, C.; He, Y.; Wang, D.; Wu, X. Biomechanical and physiological evaluation of a multi-joint exoskeleton with active-passive assistance for walking. Biosensors 2021, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, C.; Ye, C.; Fu, R. Passive and Active Training Control of an Omnidirectional Mobile Exoskeleton Robot for Lower Limb Rehabilitation. Actuators 2024, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, J.; Dwivedy, S.K. Towards neuro-fuzzy compensated PID control of lower extremity exoskeleton system for passive gait rehabilitation. IETE J. Res. 2023, 69, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovrenovic, Z.; Doumit, M. Development and testing of a passive walking assist exoskeleton. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 39, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, D.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Adaptive neural fault-tolerant prescribed performance control of a rehabilitation exoskeleton for lower limb passive training. ISA Trans. 2024, 151, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Huang, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiong, C.-H.; Mohammed, S. Echo state network-enhanced super-twisting control of passive gait training exoskeleton driven by pneumatic muscles. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 5107–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Wang, F.; Wen, Y.; Hu, F.; Han, S. A real-time CNN–BiLSTM-based classifier for patient-centered AR-SSVEP active rehabilitation exoskeleton system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Ossaba, A.; Tejada, J.C.; Rúa, S.; Núñez, J.D.; Peña, A. Myoelectric model reference adaptive control with adaptive kalman filter for a soft elbow exoskeleton. Control. Eng. Pract. 2024, 142, 105774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ma, Y.; Shao, K.; Yi, Z.; Cao, W.; Yin, M.; Xu, T.; Wu, X. The Human–Machine Interface Design Based on sEMG and Motor Imagery EEG for Lower Limb Exoskeleton Assistance System. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 6502914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.-I.; Takeya, R.; Tanaka, M. Neural signals regulating motor synchronization in the primate deep cerebellar nuclei. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Gao, X. Control of a 7-DOF robotic arm system with an SSVEP-based BCI. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2018, 28, 1850018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.; Meng, J.; Mai, X.; Zhu, X. BCI control of a robotic arm based on SSVEP with moving stimuli for reach and grasp tasks. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 3818–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Marcucci, G.; Peters, B.; Braidotti, M.C.; Muckli, L.; Faccio, D. Human-centred physical neuromorphics with visual brain-computer interfaces. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Flor, H.; Gurve, D.; Floriano, A.; Delisle-Rodriguez, D.; Mello, R.; Bastos-Filho, T. CCA-based compressive sensing for SSVEP-based brain-computer interfaces to command a robotic wheelchair. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 4010510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Reyes, F.A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Narayan, A.; Han, S.; Seyram, O.; Yu, H. A Novel Back-Support Exoskeleton With a Differential Series Elastic Actuator for Lifting Assistance. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 40, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, A.; Carrasquillo, C.; Carlson, J.; Park, J.; Iyengar, D.; Herrin, K.; Young, A.J.; Mazumdar, A. Design and validation of a versatile high torque quasidirect drive hip exoskeleton. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2023, 29, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X. A novel pump-valve coordinated controlled hydraulic system for the lower extremity exoskeleton. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 2020, 42, 2872–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Han, T.; Dong, F.; Liu, H.; Han, J. Adaptive robust force control of an underactuated walking lower limb hydraulic exoskeleton. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 2023, 45, 940–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhu, A.; Tu, Y.; Zou, J.; Zhang, X. Cable-driven and series elastic actuation coupled for a rigid–flexible spine-hip assistive exoskeleton in stoop–lifting event. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2023, 28, 2852–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Feng, K.; Zeng, B.; Gong, Z. Design and validation of a lightweight soft hip exosuit with series-wedge structures for assistive walking and running. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2021, 27, 2863–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Pei, W.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y. An open dataset for human SSVEPs in the frequency range of 1-60 Hz. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, S.; Jung, T.-P.; Gao, X. Filter bank canonical correlation analysis for implementing a high-speed SSVEP-based brain–computer interface. J. Neural Eng. 2015, 12, 046008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, T.R.; Kothe, C.A.; Chi, Y.M.; Ojeda, A.; Kerth, T.; Makeig, S.; Jung, T.-P.; Cauwenberghs, G. Real-time neuroimaging and cognitive monitoring using wearable dry EEG. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 62, 2553–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, M.; Zhang, D.; Ming, Z.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Ma, L.; Luo, J.; Zhang, J.; Suo, D. Brain-Controlled Hand Exoskeleton Based on Augmented Reality-Fused Stimulus Paradigm. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 29, 2932–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Gao, F.; Pan, D. State classification and motion description for the lower extremity exoskeleton SJTU-EX. J. Bionic Eng. 2014, 11, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora-Millan, J.S.; Moreno, J.C.; Rocon, E. Coordination between partial robotic exoskeletons and human gait: A comprehensive review on control strategies. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 842294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Du, Z.-j.; Dong, W.; Wang, W.-D. Human gait trajectory learning using online Gaussian process for assistive lower limb exoskeleton. In Wearable Sensors and Robots: Proceedings of International Conference on Wearable Sensors and Robots 2015; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCarthy, M.; Heyn, P.; Tagawa, A.; Carollo, J. Walking speed and patient-reported outcomes in young adults with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Kim, J.; Panizzolo, F.; Zhou, Y.M.; Baker, L.; Galiana, I.; Malcolm, P.; Walsh, C. Reducing the metabolic cost of running with a tethered soft exosuit. Sci. Robot. 2017, 2, eaan6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, D.; Yan, Z.; Yu, L.; Gui, L.; Yang, C.; Yang, W. Optimizing exoskeleton assistance: Muscle synergy-based actuation for personalized hip exoskeleton control. Actuators 2024, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.; Zhao, G. Hip Exoskeleton for Cycling Assistance. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Ryu, J.; Lee, G.; Yu, J.; Kang, S.W.; Kim, Y.Y. Single-Actuator Hip Exoskeleton Mechanism Design With Actuation in Frontal and Sagittal Planes: Design Methodology and Experimental Validation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 136630–136642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, K.; Lee, B.-H.; Kim, Y.-H. Effect of exercise using an exoskeletal hip-assist robot on physical function and walking efficiency in older adults. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratticò, D.; Carlo, D.D.; Silipo, G.; Laganà, F. Hybrid FEM-AI Approach for Thermographic Monitoring of Biomedical Electronic Devices. Computers 2025, 14, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, L.; Cucchi, M. Virtual reality enhanced biofeedback: Preliminary results of a short protocol. In International Symposium on Pervasive Computing Paradigms for Mental Health; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Green, C.S.; Bavelier, D. Action video game modifies visual selective attention. Nature 2003, 423, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hip | Exoskeleton Max. | Human Max. | Human Walking Max. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion/Extension | 54°/−54° | ≥54°/30° | 32°/22° |

| Abduction/Adduction | 57°/−35° | 54°/30° | 8°/6.5° |

| Model | Proposed Model | Conventional Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | |||

| Time | 37.94 s | 46.63 s | |

| CIR value | 0.0428 | 0.0597 | |

| Effective output ratio | 82.17% | 74.81% | |

| Comparison Terms | This Study | Literature [55] | Literature [40] | Literature [56] | Literature [57] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control methods | EEG + AR-VS paradigm + hybrid control | Crank-angle-triggered + HITL optimization | Quasi-stiffness Impedance control | Admittance control | Delayed Output Feedback Control |

| Driver design | Parallel drive + flexible support units | Parallel quasi-direct drive | Parallel quasi-direct drive | Single-actuator 6-bar Stephenson-III mechanism | Single actuator per hip |

| Kinematic properties | Redundant self-aligning design (parasitic force decrease 82%) | High backdrivability for low resistance | High backdrivability and trans-parency | 3-DOF spherical motion with 1-DOF actuator | Fixed structure with mechanical stoppers |

| Gait-assisted strategies | Periodic segmented hybrid control | Phase-based torque profile (Extension/Flexion) | Task-specific impedance (Walking and Lifting) | Frontal and sagittal plane assistance | Assistance/Resistance torque at hip joint in sagittal plane |

| Sensor fusion | EEG + IMU + force feedback | Motion capture + Motor encoder | IMU + Encoder | Torque sensor + IMU + Strain gauges (3-axis) | IMU + Hip joint angle/velocity sensors |

| Experimental effect | Gait symmetry increase 30% | Net metabolic cost decrease 31.4% | Metabolic cost decrease 16.7% (Lifting), decrease 19.4% (In-cline walk) | Bench validation of moment direction tracking | Gait speed, balance, muscle strength, metabolic efficiency increase |

| User adaptability | AR calibration (10 min) | Human-in-the-loop optimization (20 min) | Manual task selection and preference tuning | Multi-objective optimization (NSGA-II) | Therapist-controlled settings |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Cheng, B.; Tang, Q.; Wu, R.; Li, H. Design and Validation of a Brain-Controlled Hip Exoskeleton for Assisted Gait Rehabilitation Training. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121364

Wang C, Cheng B, Tang Q, Wu R, Li H. Design and Validation of a Brain-Controlled Hip Exoskeleton for Assisted Gait Rehabilitation Training. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121364

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chengjun, Biao Cheng, Qiang Tang, Renyuan Wu, and Huanyu Li. 2025. "Design and Validation of a Brain-Controlled Hip Exoskeleton for Assisted Gait Rehabilitation Training" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121364

APA StyleWang, C., Cheng, B., Tang, Q., Wu, R., & Li, H. (2025). Design and Validation of a Brain-Controlled Hip Exoskeleton for Assisted Gait Rehabilitation Training. Micromachines, 16(12), 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121364