Microfluidic Concentration Manipulation via Controllable AC Electroosmotic Flow

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Formulation

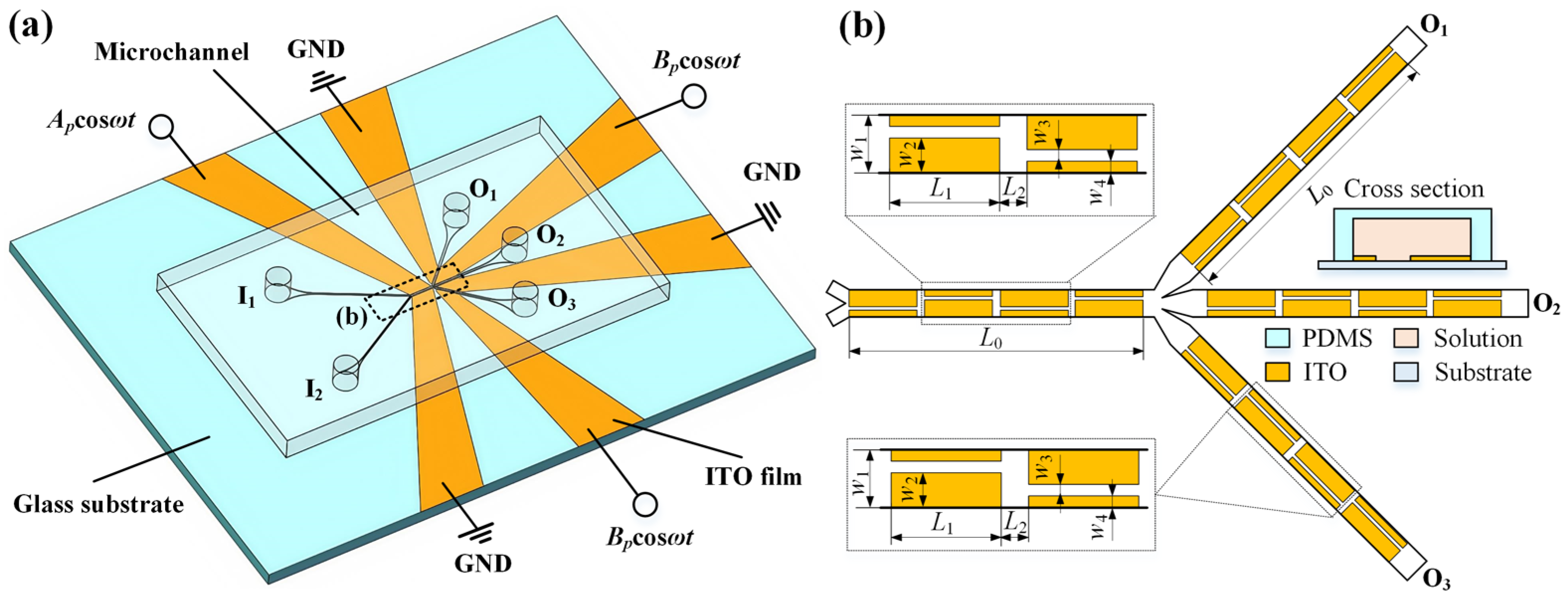

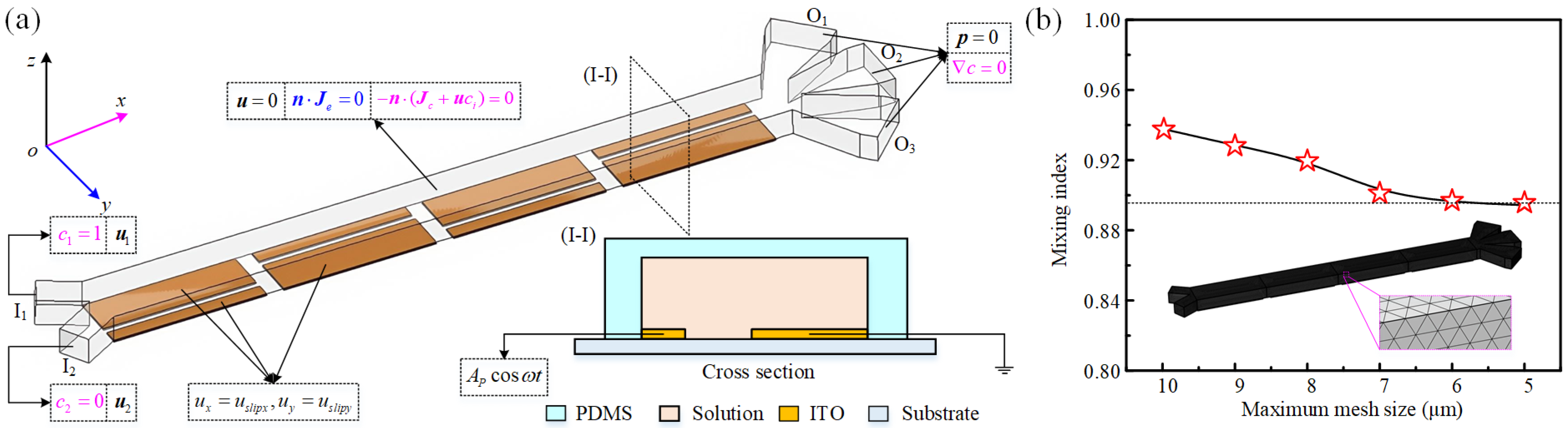

2.1. Problem Description

2.2. Theoretical Background

2.3. Solution Methodology

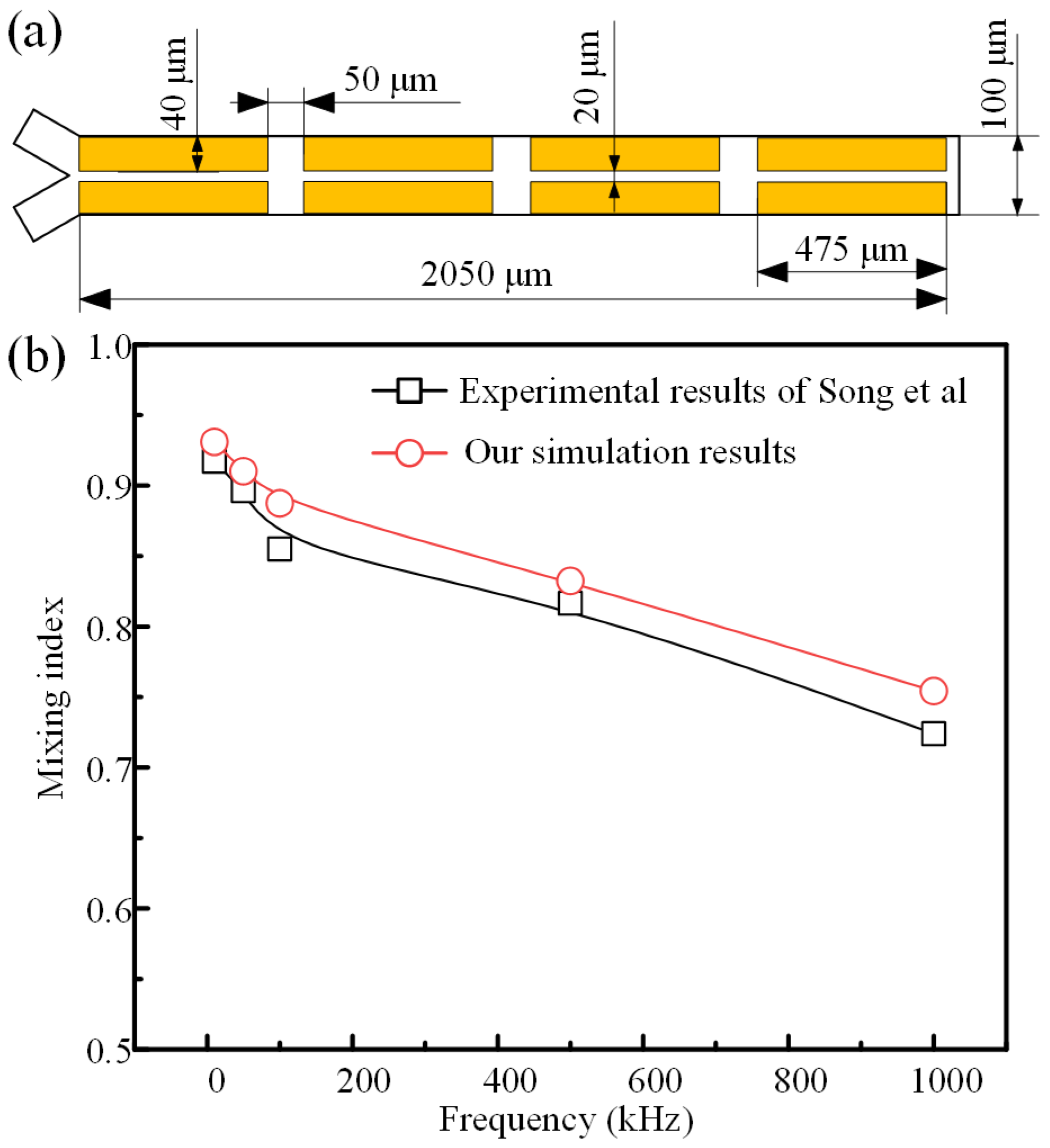

3. Results and Discussion

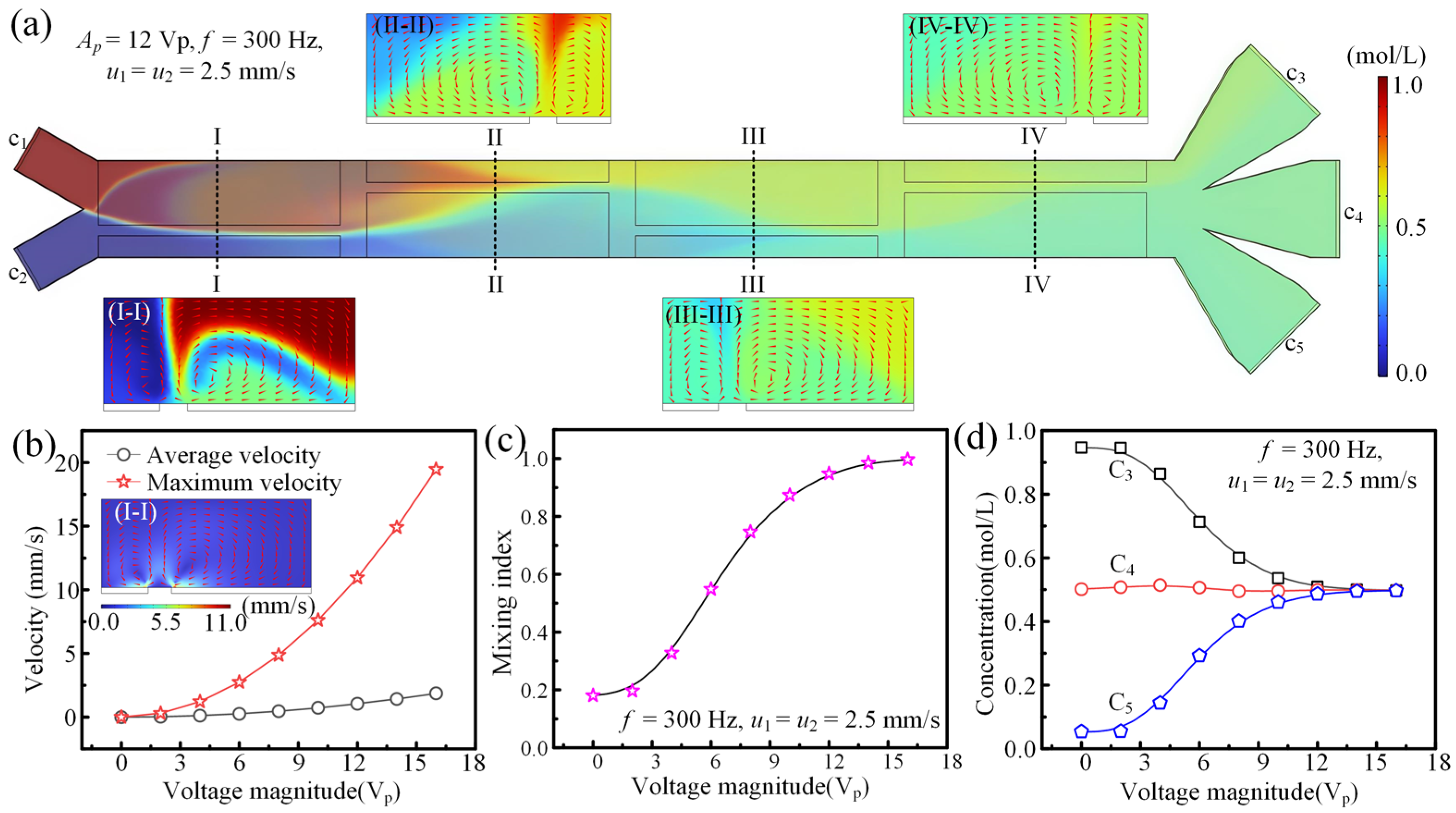

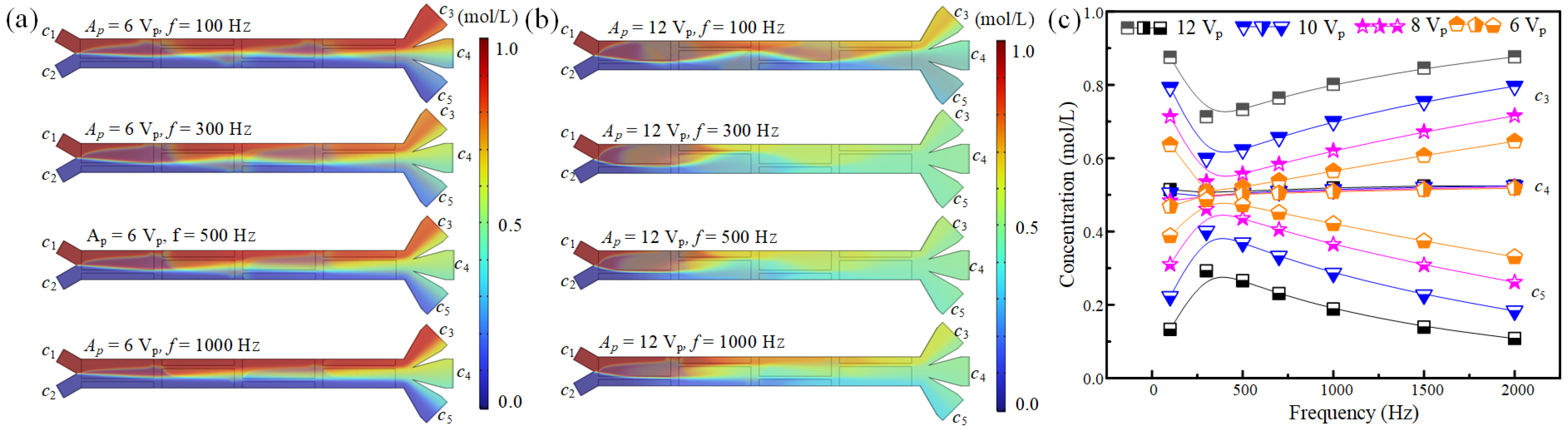

3.1. The Effect of Electric Driving Signal on Fluid Concentration Modulation

3.2. The Effect of Fluid Properties on Concentration Modulation

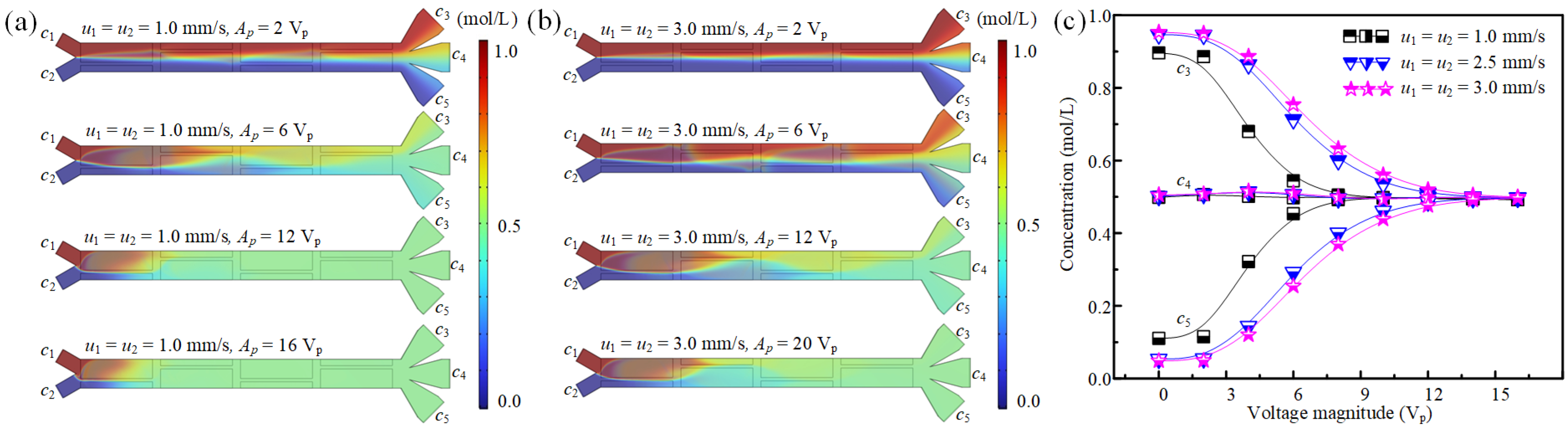

3.3. The Effect of Fluid Velocity on Concentration Modulation

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Battat, S.; Weitz, D.A.; Whitesides, G.M. An outlook on microfluidics: The promise and the challenge. Lab A Chip 2022, 22, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moragues, T.; Arguijo, D.; Beneyton, T.; Modavi, C.; Simutis, K.; Abate, A.R.; Baret, J.-C.; deMello, A.J.; Densmore, D.; Griffiths, A.D. Droplet-based microfluidics. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xing, F.; Liu, J.; Xie, Z. Flexible on-chip droplet generation, switching and splitting via controllable hydrodynamics. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1229, 340363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeren, S.; Pereira, I.F.; Wang, T.; Toonder, J.D.; Wang, Y. On-demand microfluidic mixing by actuating integrated magnetic microwalls. Lab A Chip 2023, 23, 1524–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cai, C.; Sun, H.; Wu, Y.; Xie, Z. Flexible Modulation of Droplet Concentrations via AC Electrothermal Flow for Fabrication of Crystalline Drug Particles. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 444, 138486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Hu, S.; Qian, X.; Yan, W.; Li, Y. Synthetic biology-based engineering cells for drug delivery. Exploration 2025, 5, 20240095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; He, X.; Du, Q.; Xu, L.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, D.; Liu, Y.; et al. Metal-based Smart Nanosystems in Cancer Immunotherapy. Exploration 2024, 4, 20230134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, H.; Xu, H.; Dai, W.; Xu, L.; Du, H.; Zhang, D. A review on the development and application of microfluidic concentration gradient generators. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 072014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. Machine-learning-enabled design and manipulation of a microfluidic concentration gradient generator. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Pang, Y. Concentration gradient generation methods based on microfluidic systems. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 29966–29984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Tomeh, M.A.; Ye, S.; Zhang, P.; Lv, S.; You, R.; Wang, N.; Zhao, X. Novel microfluidic swirl mixers for scalable formulation of curcumin loaded liposomes for cancer therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 622, 121857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.H.; Ping, C.H.; Sun, Y.S. Design of christmas-tree-like microfluidic gradient generators for cell-based studies. Chemosensors 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cai, C.; Sun, H.; Jia, N.; Liu, J.; Xie, Z. Flexible concentration control of Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids in a microfluidic device via AC electrothermal flow. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 380, 116043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Cai, Y.; Song, Q. An overview on state-of-art of micromixer designs, characteristics and applications. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1279, 341685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Xu, F.; Chen, G. Effective mixing in a passive oscillating micromixer with impinging jets. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhai, J.; Chen, X. A novel micromixer based on coastal fractal for manufacturing controllable size liposome. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 112009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shourabi, A.Y.; Kashaninejad, N.; Saidi, M.S. An integrated microfluidic concentration gradient generator for mechanical stimulation and drug delivery. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2021, 6, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; He, B.S.; Ruan, X.L.; Zhu, J.; Hu, R.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.-H.; Liu, M.-L. An integrated microfluidics platform with high-throughput single-cell cloning array and concentration gradient generator for efficient cancer drug effect screening. Mil. Med. Res. 2022, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ren, Y.; Ji, J.; Guo, Y.; Sun, X. A novel concentration gradient microfluidic chip for high-throughput antibiotic susceptibility testing of bacteria. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.D.; Zheng, H.; Guo, W.; Gañán-Calvo, A.M.; Ai, Y.; Tsao, C.-W.; Zhou, J.; Li, W.; Huang, Y.; Nguyen, N.-T.; et al. Active droplet sorting in microfluidics: A review. Lab A Chip 2017, 17, 751–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, S.N.; Raveshi, M.R.; Nosrati, R.; Bhardwaj, R.; Neild, A. Droplet splitting in microfluidics: A review. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 051304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenje, M.; Fornell, A.; Ohlin, M.; Nilsson, J. Particle manipulation methods in droplet microfluidics. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.P.; Lata, J.; Chen, C.; Mai, J.; Guo, F.; Tian, Z.; Ren, L.; Mao, Z.; Huang, P.H.; Li, P.; et al. Digital acoustofluidics enables contactless and programmable liquid handling. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Mirzajani, H.; Evans, B.; Greenbaum, E.; Wu, J. A disposable bulk-acoustic-wave microalga trapping device for real-time water monitoring. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 304, 127388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, R.; Lin, R.; Yan, C.; Bao, F. Microfluidic encapsulation of soluble reagents with large-scale concentration gradients in a sequence of droplets for comparative analysis. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 655, 130227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Gao, Y.; Ghaznavi, A.; Zhao, W.; Xu, J. AC electroosmosis micromixing on a lab-on-a-foil electric microfluidic device. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 359, 131611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenburg, G.; Hernández-Alpízar, H.; Lesser-Rojas, L.; Chou, C.-F. Nanoscale AC Electroosmotic Flow and the Frequency–Size Scaling Observed beyond the Charge Relaxation Regime. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 13128–13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, J.-C.; Lin, H.; Li, K.; Yi, F.-T. Study on ethanol driven by alternating current electroosmosis in microchannels. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2023, 351, 114174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terao, K.; Kondo, S. AC-electroosmosis-assisted surface plasmon resonance sensing for enhancing protein signals with a simple Kretschmann configuration. Sensors 2022, 22, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Ding, H.; Zhong, X.; Yin, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, T. Mixing mechanism of microfluidic mixer with staggered virtual electrode based on light-actuated AC electroosmosis. Micromachines 2021, 12, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavari, T.; Meamardoost, S.; Sepehry, N.; Akbarzadeh, P.; Nazari, M.; Hashemi, N.N.; Nazari, M. Effects of 3D electrodes arrangement in a novel AC electroosmotic micropump: Numerical modeling and experimental validation. Electrophoresis 2023, 44, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Zhu, C.; Dai, C.; Ye, X.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, S.; Ashraf, G.; Wei, D.; Chen, H. An alternating current electroosmotic flow-based ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescence microfluidic system for ultrafast monitoring, detection of proteins/mirnas in unprocessed samples. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2307840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, B.; Racic, M.; Tona, A.; Rao, M.V.; Gaitan, M.; Forry, S.P. Dielectrophoretic capture of mammalian cells using transparent indium tin oxide electrodes in microfluidic systems. Electrophoresis 2008, 29, 5047–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Sun, M.; Jia, N.; Xing, F.; Xie, Z. Electrically-Controlled Multifunctional Double-Emulsion Droplet Carrier Manipulation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e10679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ren, Y.; Hou, L.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, H. An efficient micromixer actuated by induced-charge electroosmosis using asymmetrical floating electrodes. Microfluid. Nanofluid 2018, 22, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Kim, M.; Oh, S.; Lee, D.B.; Lee, S.-G.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, K.H.; Song, J.; Lee, C.-S. Characterization of passive microfluidic mixer with a three-dimensional zig-zag channel for cryo-EM sampling. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 281, 119161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.T.; An, S.H.; Jeong, H.H. Microfluidic Tesla mixer with 3D obstructions to exceptionally improve the curcumin encapsulation of PLGA nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Hu, B.; Ma, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Generation of droplets with adjustable chemical concentrations based on fixed potential induced-charge electro-osmosis. Lab A Chip 2022, 22, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.O.; Song, S. Effects of multiple electrode pairs on the performance of a micromixer using dc-biased ac electro-osmosis. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2012, 22, 115034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | w1 | w2 | w3 | w4 | w5 | L0 | L1 | L2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (μm) | 180 | 120 | 20 | 40 | 40 | 1950 | 450 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, J.; Pei, Y.; Sun, J. Microfluidic Concentration Manipulation via Controllable AC Electroosmotic Flow. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111288

Lv J, Pei Y, Sun J. Microfluidic Concentration Manipulation via Controllable AC Electroosmotic Flow. Micromachines. 2025; 16(11):1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111288

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Jingliang, Yulong Pei, and Jianqi Sun. 2025. "Microfluidic Concentration Manipulation via Controllable AC Electroosmotic Flow" Micromachines 16, no. 11: 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111288

APA StyleLv, J., Pei, Y., & Sun, J. (2025). Microfluidic Concentration Manipulation via Controllable AC Electroosmotic Flow. Micromachines, 16(11), 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111288