Numerical Investigation of Crack Suppression Strategies in Ultra-Thin Glass Substrates for Advanced Packaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

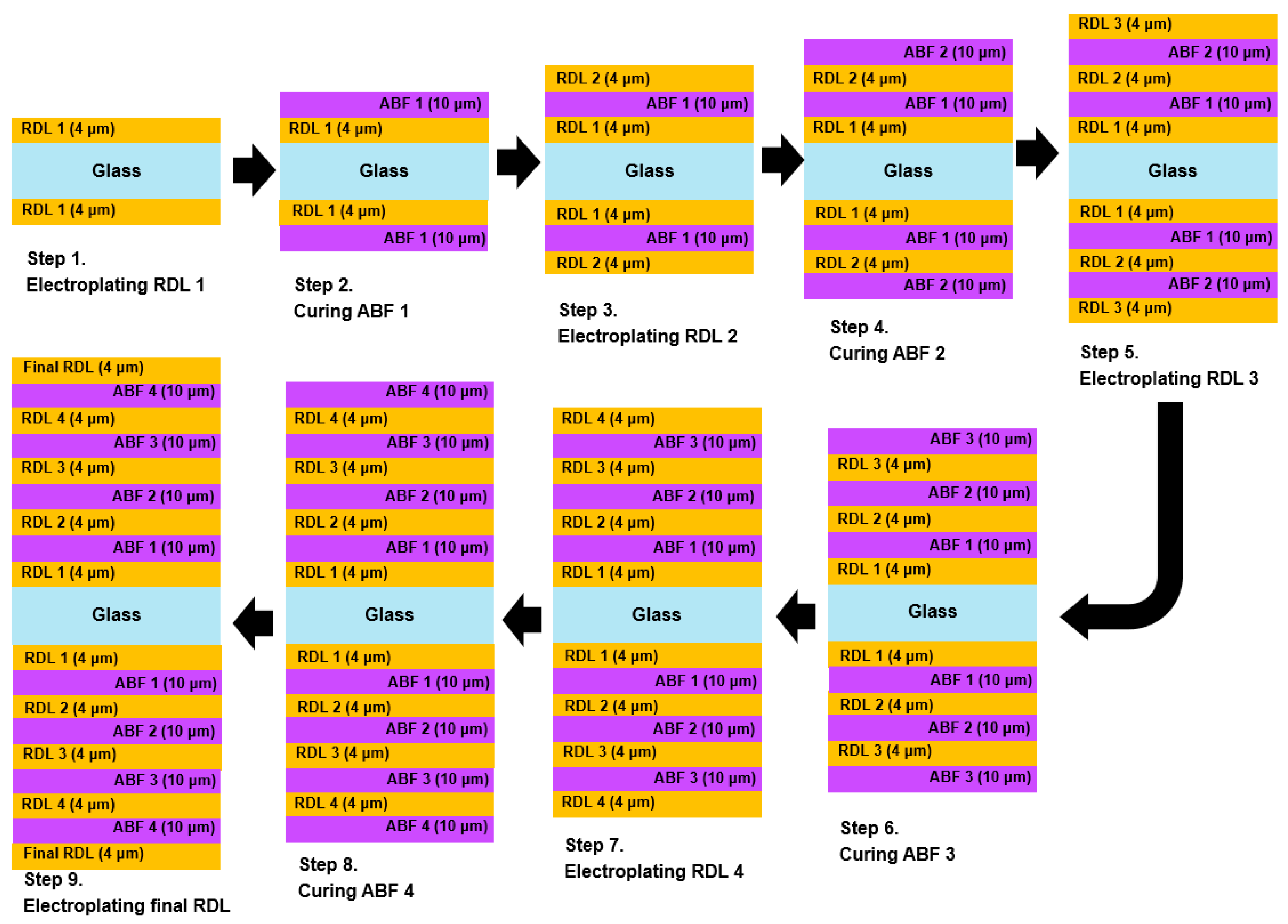

2. Simulation Modeling and Boundary Condition

2.1. Equivalent RDL Architecture and Material Properties

2.2. Mesh Modeling and Edge Crack Definition

2.3. Process-Oriented Simulation of RDL Fabrication

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Crack Location and the Number of RDLs on the Risk of Crack Propagation

3.2. Effect of Glass Thickness and Glass Materials on Risk of Crack Propagation

3.3. Effect of ABF Materials and Cu Content on Risk of Crack Propagation

3.4. Effect of Edge-Clearance on Risk of Crack Propagation in Glass Panel

4. Conclusions

- Top-edge cracks near the RDL/glass interface pose the greatest risk compared to center-edge cracks. The risk of crack propagation increases linearly with the number of RDLs, with four-layer structures exceeding the fracture threshold.

- Thinner glass panels only slightly increase the risk of crack propagation; however, at 100 µm thickness, the trend becomes pronounced, and the glass is highly vulnerable to cracking.

- The choice of glass material has a pronounced impact on crack suppression. High-CTE glasses, including D263, Gorilla, and ceramic glass, effectively mitigate the risk of propagation.

- Selecting appropriate ABF materials is also crucial for crack resistance. GZ-41 is a superior candidate for suppressing cracking due to their favorable combination of low CTE and moderate Young’s modulus.

- Reducing edge clearance markedly increases the risk of edge crack propagation, whereas maintaining a clearance of at least 300 µm from Cu vias to the glass edge is essential for effective crack suppression.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lau, J.H. Recent advances and trends in advanced packaging. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 12, 228–252. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Chen, Q.; Suzuki, Y.; Kumar, G.; Sundaram, V.; Tummala, R.R. Modeling, fabrication, and characterization of low-cost and high-performance polycrystalline panel-based silicon interposer with through vias and redistribution layers. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 4, 2035–2041. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Le, X.B.; Choa, S.H. Assessment of the Risk of Crack Formation at a Hybrid Bonding Interface Using Numerical Analysis. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, V.; Chen, Q.; Wang, T.; Lu, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Smet, V.; Kobayashi, M.; Pulugurtha, R.; Tummala, R. Low cost, high performance, and high reliability 2.5D silicon interposer. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 63rd Electronic Components and Technology Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 28–31 May 2013; pp. 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran, V.; Kumar, G.; Ramachandran, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Demir, K.; Sato, Y.; Tummala, R.R. Design, fabrication, and characterization of ultrathin 3-D glass interposers with through package-vias at same pitch as TSVs in silicon. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 4, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, B.M.; Suzuki, Y.; Furuya, R.; Nair, C.; Huang, T.C.; Smet, V.; Panayappan, K.; Sundaram, V.; Tummala, R. Design and demonstration of a 2.5-D glass interposer BGA package for high bandwidth and low cost. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 7, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, K.; Armutlulu, A.; Sundaram, V.; Raj, P.M.; Tummala, R.R. Reliability of copper through-package vias in bare glass interposers. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 7, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Gao, J. The adhesion of copper films coated on silicon and glass substrates. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2000, 14, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, X.B.; Choa, S.H. A comprehensive numerical analysis for preventing cracks in 2.5 D glass interposer. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 3027–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, S.R.; Sato, Y.; Sundaram, V.; Tummala, R.R.; Sitaraman, S.K. Study of cracking of thin glass interposers intended for microelectronic packaging substrates. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 65th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 26–29 May 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, F.; Sundaram, V.; McCann, S.; Smet, V.; Tummala, R. Empirical investigations on die edge defects reductions in die singulation processes for glass-panel based interposers for advanced packaging. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 65th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 26–29 May 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-C.; Chang, C.-P.; Huang, P.-C. Development and demonstration on process-oriented warpage simulation methodology of fan-out panel-level package in multilevel integration. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 13, 2016–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Wang, C.-W.; Chen, C.-Y. Comparison of mechanical modeling to warpage estimation of RDL-first fan-out panel-level packaging. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 12, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Wang, C.-W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Lee, H.-C.; Chou, T.-S. Warpage estimation of heterogeneous panel-level fan-out package with fine line RDL and extreme thin laminated substrate considering molding characteristics. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 71st Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 1–4 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-C.; Liou, Y.-Y.; Huang, P.-C.; Hsu, F.; Lin, P.B.; Ko, C.-T.; Chen, Y.-H. Comprehensive investigation on warpage management of FOPLP with multi embedded ring designs. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 69th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 28–31 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.Y.; Lin, P.B.; Ko, C.T.; Wang, C.W.; Chuang, O.; Lee, C.C. A novel warpage reinforcement architecture with RDL interposer for heterogeneous integrated packages. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 70th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Orlando, FL, USA, 3–30 June 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.-C.; Lin, Y.-M.; Liu, H.-N.; Lee, C.-C. Process-induced warpage and stress estimation of through glass via embedded interposer carrier with ring-type framework. Microelectron. Reliab. 2022, 129, 114476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, S.; Singh, B.; Smet, V.; Sundaram, V.; Tummala, R.R.; Sitaraman, S.K. Process innovations to prevent glass substrate fracture from RDL stress and singulation defects. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2016, 16, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, S.; Lee, T.; Gandhi, J.; Ramalingam, S. Core Cracking in Advanced Organic Substrates Due to Free Edge Effect at Cold Temperatures. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 11, 1917–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, S.; Sato, Y.; Ogawa, T.; Tummala, R.R.; Sitaraman, S.K. Use of birefringence to determine redistribution layer stresses to create design guidelines to prevent glass cracking. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2017, 17, 585–592. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, S.; Sato, Y.; Sundaram, V.; Tummala, R.R.; Sitaraman, S.K. Prevention of cracking from RDL stress and dicing defects in glass substrates. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2015, 16, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunohara, M.; Yoshiike, J.; Taneda, H.; Nakabayashi, Y.; Shimizu, N. Development of Glass Core Build-up Substate with TGV. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 75th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Dallas, TX, USA, 27–30 May 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-C.; Chang, C.-P.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lee, H.-C.; Chen, G.C.-F. Warpage estimation and demonstration of panel-level fan-out packaging with Cu pillars applied on a highly integrated architecture. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 13, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Pan, K.; Park, S. Thermo-mechanical reliability of glass substrate and Through Glass Vias (TGV): A comprehensive review. Microelectron. Reliab. 2024, 161, 115477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.H. Recent advances and trends in multiple system and heterogeneous integration with TSV interposers. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 13, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Fang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Q. Research progress of interfacial adhesion force of copper plating on Ajinomoto build-up films for chip substrates. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, S.; Fujishima, S.; Sakauchi, H. Advanced build-up materials for high speed transmission application. Int. Symp. Microelectron. 2018, 2018, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbalkar, P.; Bhaskar, P.; Kathaperumal, M.; Swaminathan, M.; Tummala, R.R. A review of polymer dielectrics for redistribution layers in interposers and package substrates. Polymers 2023, 15, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCHOTT AG. SCHOTT BOROFLOAT® Glass—Technical Details. SCHOTT Website. Available online: https://www.schott.com/ko-kr/products/borofloat-p1000314/downloads (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Anderson, T.L.; Anderson, T.L. Fracture Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, S.; Smet, V.; Sundaram, V.; Tummala, R.R.; Sitaraman, S.K. Experimental and theoretical assessment of thin glass substrate for low warpage. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 7, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, S. Design for Mechanical Reliability of Redistribution Layers for Ultra-Thin 2.5 D Glass Packages. Ph.D. Dissertation, George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Birman, V. Plates and shells. In Encyclopedia of Aerospace Engineering; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 15, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, O.; Jalilvand, G.; Pollard, S.; Okoro, C.; Jiang, T. The interfacial reliability of through-glass vias for 2.5 D integrated circuits. Microelectron. Int. 2020, 37, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCHOTT, AG. SCHOTT D 263® Glass—Technical Details. SCHOTT Website. Available online: https://www.schott.com/en-gb/products/d-263-p1000318/technical-details (accessed on 28 October 2025).

| Materials | E (GPa) | ν | α (ppm/°C) | Stress-Free Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | 91.7 | 0.34 | 17.6 | 110 |

| ABF GX-92 | 5 | 0.3 | 39 | 180 |

| Borofloat 33 glass | 64 | 0.2 | 3.25 | 25 |

| Ex (GPa) | Ez (GPa) | νxy | νxz | Gxy (GPa) | Gxz (GPa) | αxy (ppm/°C) | αxz (ppm/°C) | Stress-Free Temperature (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDL | 10.21 | 48.35 | 0.316 | 0.32 | 3.64 | 18.07 | 31.15 | 18.71 | 117 |

| Materials | E (GPa) | ν | α (ppm/°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fused silica | 73 | 0.16 | 0.57 |

| Borofloat 33 | 64 | 0.2 | 3.25 |

| D 263 | 72.9 | 0.21 | 7.2 |

| Gorilla | 71.5 | 0.21 | 8.14 |

| Ceramic | 67 | 0.29 | 9.3 |

| ABF Materials | E (GPa) | ν | α (ppm/°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GL-102 | 13 | 0.3 | 20 |

| GX-92 | 5 | 0.3 | 39 |

| GZ-22 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 31 |

| GZ-41 | 9 | 0.3 | 20 |

| Cu Content (%) | Ex (GPa) | Ez (GPa) | νxy | νxz | Gxy (GPa) | Gxz (GPa) | αxy (ppm/°C) | αxz (ppm/°C) | Stress-Free Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 5.83 | 13.67 | 0.386 | 0.304 | 2.12 | 5.51 | 37.5 | 24.6 | 147 |

| 20 | 6.59 | 22.34 | 0.356 | 0.308 | 2.37 | 8.38 | 36.7 | 21.4 | 132 |

| 30 | 7.49 | 31.01 | 0.338 | 0.312 | 2.68 | 11.61 | 35.3 | 20.2 | 125 |

| 40 | 8.65 | 39.68 | 0.325 | 0.316 | 3.09 | 14.84 | 33.8 | 19.2 | 121 |

| 50 | 10.21 | 48.35 | 0.316 | 0.32 | 3.64 | 18.07 | 31.15 | 18.71 | 117 |

| 60 | 12.43 | 57.02 | 0.308 | 0.324 | 4.43 | 21.3 | 28.5 | 18.4 | 115 |

| 70 | 15.88 | 65.69 | 0.303 | 3.28 | 5.21 | 24.5 | 25.8 | 18.1 | 113 |

| 80 | 21.93 | 74.36 | 0.298 | 3.32 | 6.12 | 27.3 | 23.1 | 17.9 | 112 |

| 90 | 35.41 | 83.03 | 0.294 | 0.36 | 7.15 | 30.75 | 20.3 | 17.7 | 111 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le, X.-B.; Yoo, K.-Y.; Choa, S.-H. Numerical Investigation of Crack Suppression Strategies in Ultra-Thin Glass Substrates for Advanced Packaging. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111256

Le X-B, Yoo K-Y, Choa S-H. Numerical Investigation of Crack Suppression Strategies in Ultra-Thin Glass Substrates for Advanced Packaging. Micromachines. 2025; 16(11):1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111256

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe, Xuan-Bach, Kee-Youn Yoo, and Sung-Hoon Choa. 2025. "Numerical Investigation of Crack Suppression Strategies in Ultra-Thin Glass Substrates for Advanced Packaging" Micromachines 16, no. 11: 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111256

APA StyleLe, X.-B., Yoo, K.-Y., & Choa, S.-H. (2025). Numerical Investigation of Crack Suppression Strategies in Ultra-Thin Glass Substrates for Advanced Packaging. Micromachines, 16(11), 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111256