Preclinical Assessment of a New Polyvalent Antivenom (Inoserp Europe) against Several Species of the Subfamily Viperinae

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

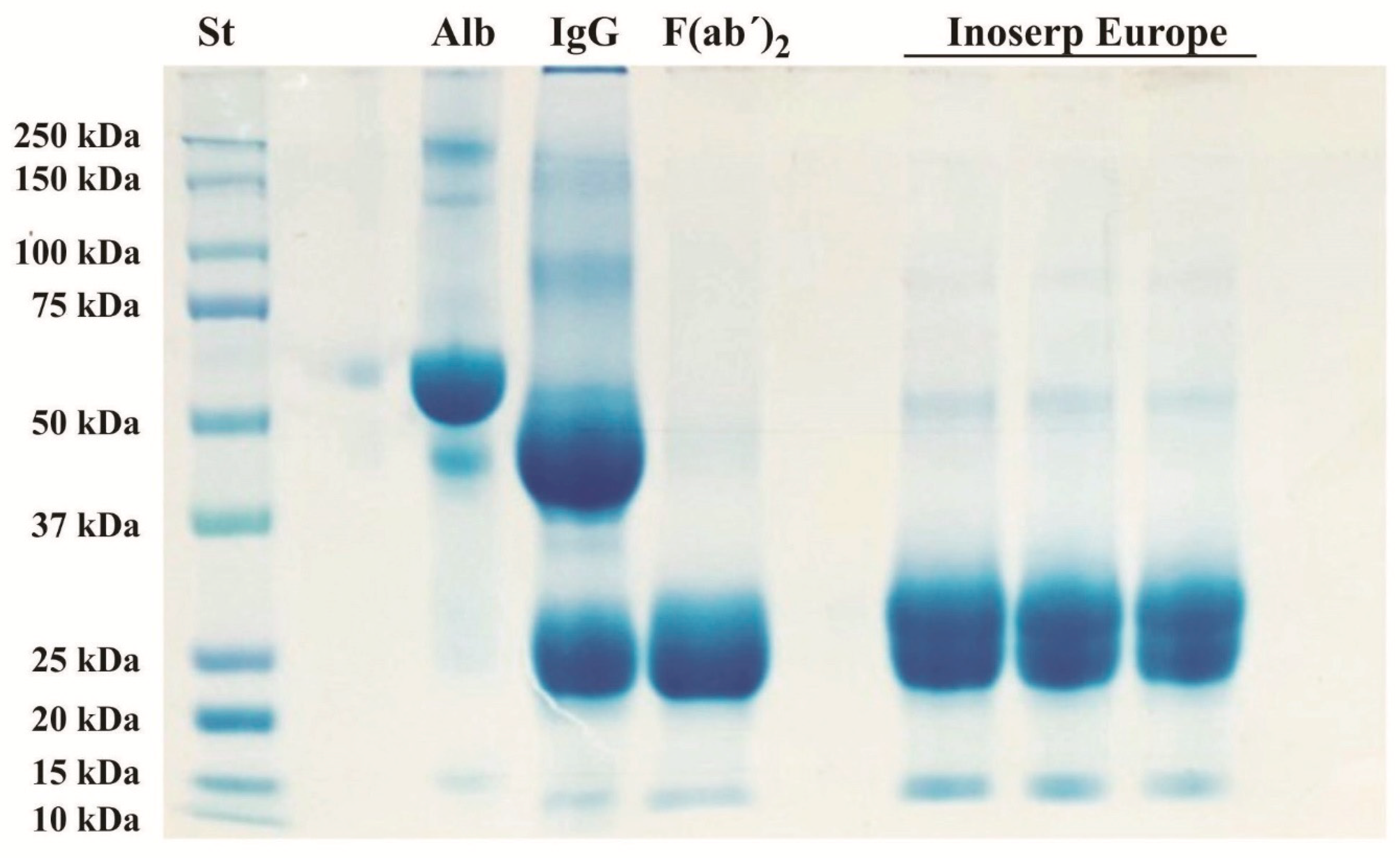

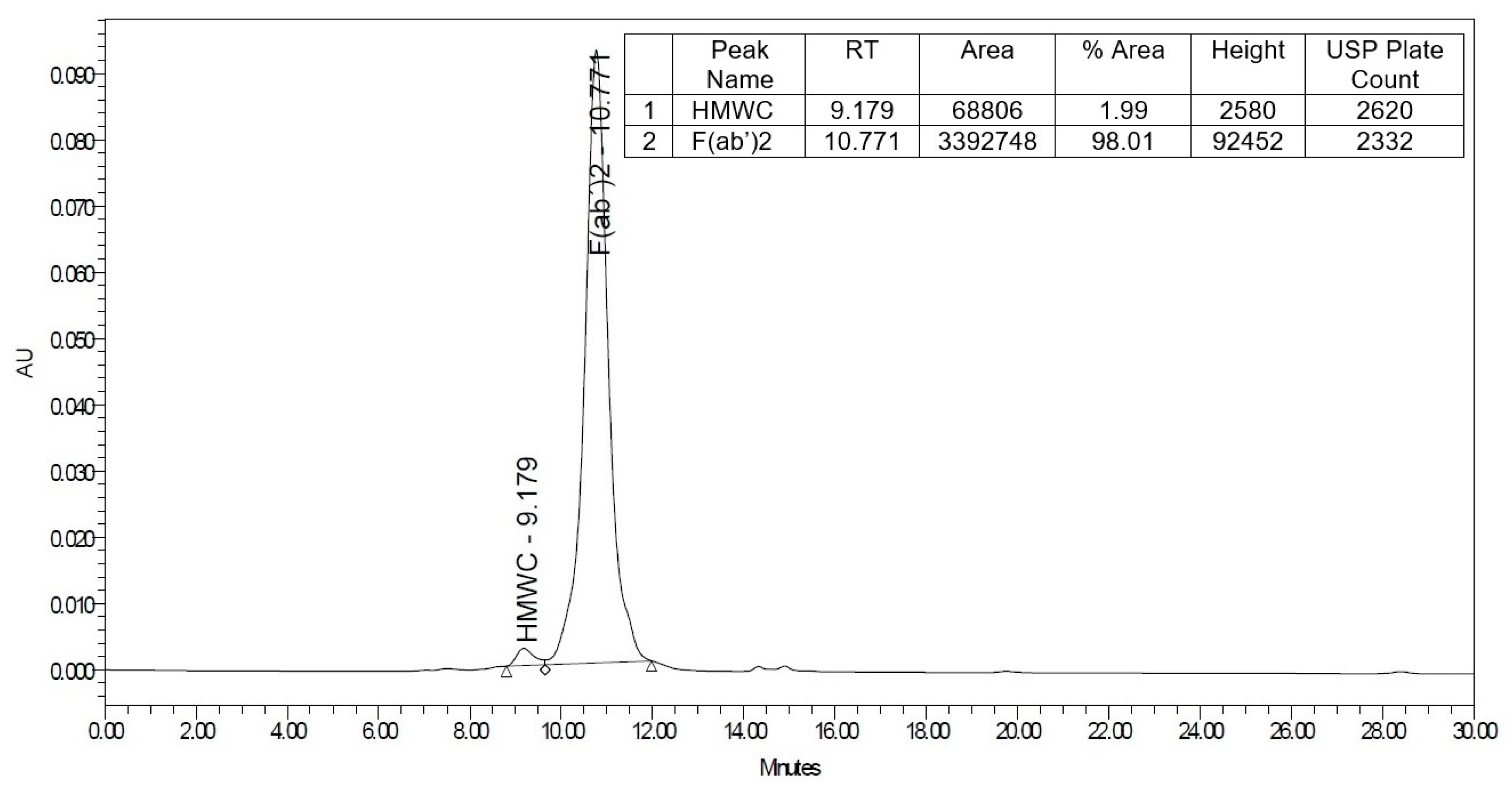

2.1. Physicochemical and Biochemical Characteristics of the Antivenom

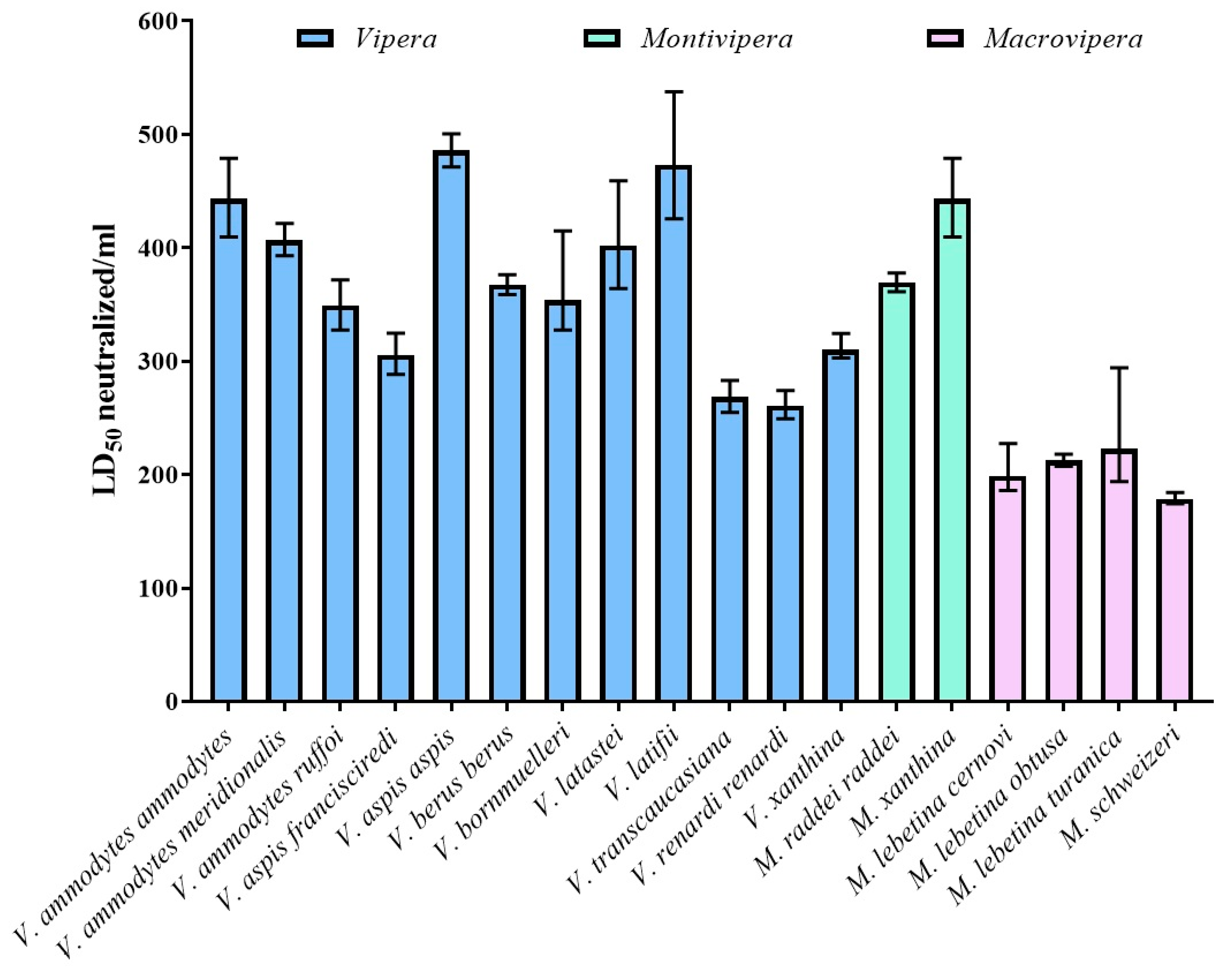

2.2. Neutralization of Lethality (Paraspecificity Evaluation)

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Venoms

5.2. Animal Handling

5.3. Antivenom Production

5.4. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

5.5. Analysis by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

5.6. Neutralization of Lethality (Paraspecificity Evaluation)

5.7. Data Analysis and Statistics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Venomous Snakes Distribution and Species Risk Categories. Available online: http://apps.who.int/bloodproducts/snakeantivenoms/database/ (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins. Annex 5. WHO Tech. Ser. 2017, 204, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J. Epidemiology of Snakebites in Europe: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Toxicon 2012, 59, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabuva, S.; Vrkić, I.; Brizić, I.; Ivić, I.; Lukšić, B. Venomous Snakebites in Children in Southern Croatia. Toxicon 2016, 112, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesaretli, Y.; Ozkan, O. Snakebites in Turkey: Epidemiological and Clinical Aspects between the Years 1995 and 2004. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2010, 16, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, R.; Sula, B.; Cakır, G.; Aktar, F.; Deveci, Ö.; Yolbas, I.; Çelen, M.K.; Bekcibasi, M.; Palancı, Y.; Dogan, E. Comparison of Snakebite Cases in Children and Adults. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 2711–2716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Latinović, Z.; Leonardi, A.; Šribar, J.; Sajevic, T.; Žužek, M.C.; Frangež, R.; Halassy, B.; Trampuš-Bakija, A.; Pungerčar, J.; Križaj, I. Venomics of Vipera Berus Berus to Explain Differences in Pathology Elicited by Vipera Ammodytes Ammodytes Envenomation: Therapeutic Implications. J. Proteom. 2016, 146, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Zahran, T.; Kazzi, Z.; Chehadeh, A.A.-H.; Sadek, R.; El Sayed, M.J. Snakebites in Lebanon: A Descriptive Study of Snakebite Victims Treated at a Tertiary Care Center in Beirut, Lebanon. J. Emerg. Trauma. Shock 2018, 11, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audebert, F.; Sorkine, M.; Bon, C. Envenoming by Viper Bites in France: Clinical Gradation and Biological Quantification by ELISA. Toxicon 1992, 30, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audebert, F.; Sorkine, M.; Robbe-Vincent, A.; Bon, C. Viper Bites in France: Clinical and Biological Evaluation; Kinetics of Envenomations. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1994, 13, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boels, D.; Hamel, J.F.; Deguigne, M.B.; Harry, P. European Viper Envenomings: Assessment of ViperfavTM and Other Symptomatic Treatments. Clin. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenta, J.; Stach, Z.; Stříteský, M.; Michálek, P. Common Viper Bites in the Czech Republic—Epidemiological and Clinical Aspects during 15 Year Period (1999–2013). Prague Med. Rep. 2014, 115, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jollivet, V.; Hamel, J.F.; de Haro, L.; Labadie, M.; Sapori, J.M.; Cordier, L.; Villa, A.; Nisse, P.; Puskarczyk, E.; Berthelon, L.; et al. European Viper Envenomation Recorded by French Poison Control Centers: A Clinical Assessment and Management Study. Toxicon 2015, 108, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, T.; de Haro, L.; Lonati, D.; Brvar, M.; Eddleston, M. Antivenom for European Vipera Species Envenoming. Clin. Toxicol. 2017, 55, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, M.; Abd-Elsalam, M.A.; Al-Ahaidib, M.S. Pharmacokinetics of 125I-Labelled Walterinnesia Aegyptia Venom and Its Distribution of the Venom and Its Toxin versus Slow Absorption and Distribution of IGG, F(AB’)2 and F(AB) of the Antivenin. Toxicon 1998, 36, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, S.P.; Ruha, A.-M.; Seifert, S.A.; Morgan, D.L.; Lewis, B.J.; Arnold, T.C.; Clark, R.F.; Meggs, W.J.; Toschlog, E.A.; Borron, S.W.; et al. Comparison of F(Ab’) 2 versus Fab Antivenom for Pit Viper Envenomation: A Prospective, Blinded, Multicenter, Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Toxicol. 2015, 53, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, V. Antivenom Therapy: Efficacy of Premedication for the Prevention of Adverse Reactions. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luksić, B.; Bradarić, N.; Prgomet, S. Venomous Snakebites in Southern Croatia. Coll. Antropol. 2006, 30, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karabuva, S.; Brizić, I.; Latinović, Z.; Leonardi, A.; Križaj, I.; Lukšić, B. Cardiotoxic Effects of the Vipera Ammodytes Ammodytes Venom Fractions in the Isolated Perfused Rat Heart. Toxicon 2016, 121, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanetti, G.; Duregotti, E.; Locatelli, C.A.; Giampreti, A.; Lonati, D.; Rossetto, O.; Pirazzini, M. Variability in Venom Composition of European Viper Subspecies Limits the Cross-Effectiveness of Antivenoms. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón, L.; Lomonte, B.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Tarkowski, A.; Hanson, L.A. Biological and Biochemical Activities of Vipera Berus (European Viper) Venom. Toxicon 1993, 31, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, B.; Roeggla, G. Vipera Berus Bite in a Child, with Severe Local Symptoms and Hypotension. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2009, 20, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czajka, U.; Wiatrzyk, A.; Lutyńska, A. Mechanism of Vipera Berus Venom Activity and the Principles of Antivenom Administration in Treatment. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2013, 67, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malina, T.; Krecsak, L.; Warrell, D.A. Neurotoxicity and Hypertension Following European Adder (Vipera Berus Berus) Bites in Hungary: Case Report and Review. QJM 2008, 101, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malina, T.; Babocsay, G.; Krecsák, L.; Erdész, C. Further Clinical Evidence for the Existence of Neurotoxicity in a Population of the European Adder (Vipera Berus Berus) in Eastern Hungary: Second Authenticated Case. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2013, 24, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malina, T.; Krecsák, L.; Westerström, A.; Szemán-Nagy, G.; Gyémánt, G.; M-Hamvas, M.; Rowan, E.G.; Harvey, A.L.; Warrell, D.A.; Pál, B.; et al. Individual Variability of Venom from the European Adder (Vipera Berus Berus) from One Locality in Eastern Hungary. Toxicon 2017, 135, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocian, A.; Urbanik, M.; Hus, K.; Łyskowski, A.; Petrilla, V.; Andrejčáková, Z.; Petrillová, M.; Legath, J. Proteome and Peptidome of Vipera Berus Berus Venom. Molecules 2016, 21, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halassy, B.; Brgles, M.; Habjanec, L.; Balija, M.L.; Kurtović, T.; Marchetti-Deschmann, M.; Križaj, I.; Allmaier, G. Intraspecies Variability in Vipera Ammodytes Ammodytes Venom Related to Its Toxicity and Immunogenic Potential. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2011, 153, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, F.M.S.; Casewell, N.R.; Al-Abdulla, I.; Landon, J. Production and Assessment of Ovine Antisera for the Manufacture of a Veterinary Adder Antivenom. Vet. Rec. 2014, 174, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archundia, I.G.; de Roodt, A.R.; Ramos-Cerrillo, B.; Chippaux, J.-P.; Olguín-Pérez, L.; Alagón, A.; Stock, R.P. Neutralization of Vipera and Macrovipera Venoms by Two Experimental Polyvalent Antisera: A Study of Paraspecificity. Toxicon 2011, 57, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casewell, N.R.; Al-Abdulla, I.; Smith, D.; Coxon, R.; Landon, J. Immunological Cross-Reactivity and Neutralisation of European Viper Venoms with the Monospecific Vipera Berus Antivenom ViperaTAb. Toxins 2014, 6, 2471–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Venom | Origin | LD50 in µg/Mouse (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Vipera ammodytes ammodytes ** | Albania | 8.07 (7.48–8.54) |

| Vipera ammodytes meridionalis ** | Greece | 7.34 (6.20–8.16) |

| Vipera ammodytes ruffoi ** | Italy | 8.29 (7.14–8.95) |

| Vipera aspis francisciredi ** | Switzerland | 12.78 (10.51–14.05) |

| Vipera aspis aspis * | France | 8.42 (7.65–9.38) |

| Vipera berus berus * | Turkey | 5.28 (5.06–5.48) |

| Vipera bornmuelleri * | Lebanon | 11.32 (11.14–11.52) |

| Vipera latastei * | Spain | 8.17 (7.09–9.01) |

| Vipera latifii * | Iran | 5.52 (4.88–6.16) |

| Vipera transcaucasiana ** | Turkey | 8.13 (6.94–9.03) |

| Vipera renardi renardi ** | Romania | 11.84 (10.91–12.70) |

| Vipera xanthina * | Turkey | 7.03 (6.85–7.16) |

| Montivipera raddei raddei ** | Turkey | 4.08 (3.21–4.59) |

| Montivipera xanthina ** | Turkey | 7.17 (5.87–8.10) |

| Macrovipera lebetina cernovi * | Turkmenistan | 19.71 (18.34–20.60) |

| Macrovipera lebetina obtusa * | Azerbaijan | 16.32 (15.73–16.93) |

| Macrovipera lebetina turanica * | Russia | 18.36 (17.17–19.30) |

| Macrovipera schweizeri ** | Greece | 17.32 (16.87–18.11) |

| Venom | ED50 in µL (95% c.i.) | ED50 in mg/mL (95% CI) | ED50 in mg/vial (95% CI) | LD50 Neutralized/vial (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vipera ammodytes ammodytes | 11.28 (10.44–12.21) | 3.58 (3.30–3.86) | 35.77 (33.05–38.65) | 4432.6 (4095.0–4789.3) |

| Vipera ammodytes meridionalis | 12.29 (11.86–12.72) | 2.99 (2.89–3.09) | 29.86 (28.85–30.94) | 4068.3 (3930.8–4215.9) |

| Vipera ammodytes ruffoi | 14.32 (13.45–15.26) | 2.89 (2.72–3.08) | 28.95 (27.16–30.82) | 3491.6 (3276.5–3717.5) |

| Vipera aspis francisciredi | 16.35 (15.39–17.33) | 3.91 (3.69–4.15) | 39.08 (36.87–41.52) | 3058.1 (2885.2–3248.9) |

| Vipera aspis aspis | 10.29 (9.99–10.61) | 4.09 (3.97–4.22) | 40.94 (39.70–42.18) | 4859.1 (4712.5–5006.0) |

| Vipera berus berus | 13.61 (13.29–13.94) | 1.94 (1.89–1.98) | 19.38 (18.92–19.85) | 3673.8 (3586.8–3762.2) |

| Vipera bornmuelleri | 14.14 (12.05–15.26) | 4.00 (3.71–4.70) | 40.03 (37.09–46.97) | 3536.1 (3276.5–4149.4) |

| Vipera latastei | 12.44 (10.89–13.73) | 3.28 (2.98–3.75) | 32.84 (29.75–37.51) | 4019.3 (3641.7–4591.4) |

| Vipera latifii | 10.57 (9.30–11.75) | 2.61 (2.35–2.97) | 26.12 (23.50–29.69) | 4730.4 (4255.3–5376.9) |

| Vipera transcaucasiana | 18.63 (17.66–19.65) | 2.18 (2.07–2.30) | 21.82 (20.73–23.02) | 2683.8 (2549.7–2831.3) |

| Vipera renardi renardi | 19.15 (18.23–20.06) | 3.09 (2.95–3.25) | 30.91 (29.51–32.47) | 2611.0 (2492.5–2742.7) |

| Vipera xanthina | 16.13 (15.41–16.51) | 2.18 (2.13–2.28) | 21.78 (21.28–22.80) | 3099.8 (3028.5–3244.5) |

| Montivipera raddei raddei | 13.53 (13.23–13.84) | 1.51 (1.47–1.54) | 15.08 (14.74–15.42) | 3695.5 (3612.7–3779.3) |

| Montivipera xanthina | 11.28 (10.44–12.21) | 3.18 (2.94–3.43) | 31.78 (29.36–34.34) | 4432.6 (4095.0–4789.3) |

| Macrovipera lebetina cernovi | 25.14 (21.99–26.87) | 3.92 (3.67–4.48) | 39.20 (36.68–44.82) | 1988.9 (1860.8–2273.8) |

| Macrovipera lebetina obtusa | 23.53 (22.94–24.11) | 3.47 (3.38–3.56) | 34.68 (33.84–35.57) | 2124.9 (2073.8–2179.6) |

| Macrovipera lebetina turanica | 22.42 (16.99–25.78) | 4.09 (3.56–5.40) | 40.95 (35.61–54.03) | 2230.2 (1939.5–2942.9) |

| Macrovipera schweizeri | 27.96 (27.13–28.66) | 3.10 (3.02–3.19) | 30.97 (30.22–31.92) | 1788.3 (1744.6–1843.0) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Arredondo, A.; Martínez, M.; Calderón, A.; Saldívar, A.; Soria, R. Preclinical Assessment of a New Polyvalent Antivenom (Inoserp Europe) against Several Species of the Subfamily Viperinae. Toxins 2019, 11, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11030149

García-Arredondo A, Martínez M, Calderón A, Saldívar A, Soria R. Preclinical Assessment of a New Polyvalent Antivenom (Inoserp Europe) against Several Species of the Subfamily Viperinae. Toxins. 2019; 11(3):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11030149

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Arredondo, Alejandro, Michel Martínez, Arlene Calderón, Asunción Saldívar, and Raúl Soria. 2019. "Preclinical Assessment of a New Polyvalent Antivenom (Inoserp Europe) against Several Species of the Subfamily Viperinae" Toxins 11, no. 3: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11030149

APA StyleGarcía-Arredondo, A., Martínez, M., Calderón, A., Saldívar, A., & Soria, R. (2019). Preclinical Assessment of a New Polyvalent Antivenom (Inoserp Europe) against Several Species of the Subfamily Viperinae. Toxins, 11(3), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11030149