Fructose and Sucrose Intake Increase Exogenous Carbohydrate Oxidation during Exercise

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Pretesting

2.3. Diet and Activity before Testing

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Protocol

2.6. Analyses

2.7. Calculations

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

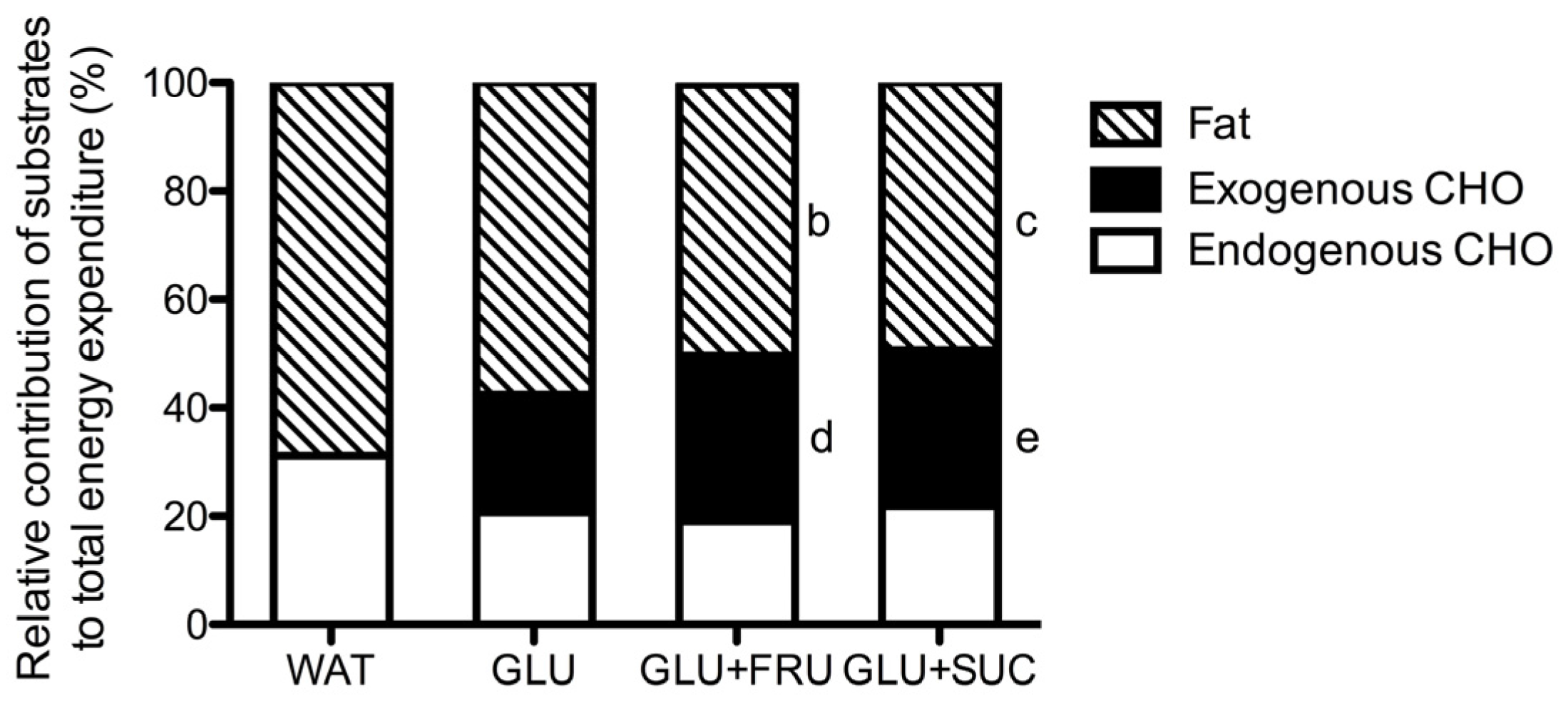

3.1. Indirect Calorimetry

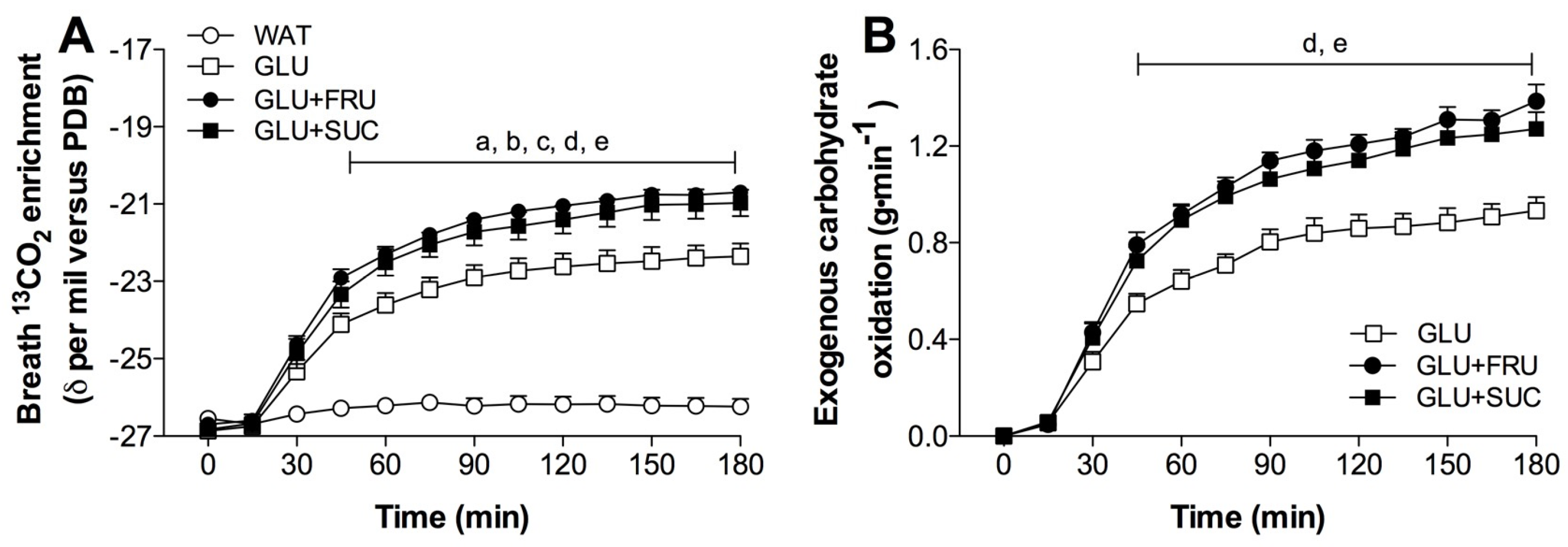

3.2. Stable-Isotope Measurements

3.3. Exogenous and Endogenous Carbohydrate Oxidation Rates

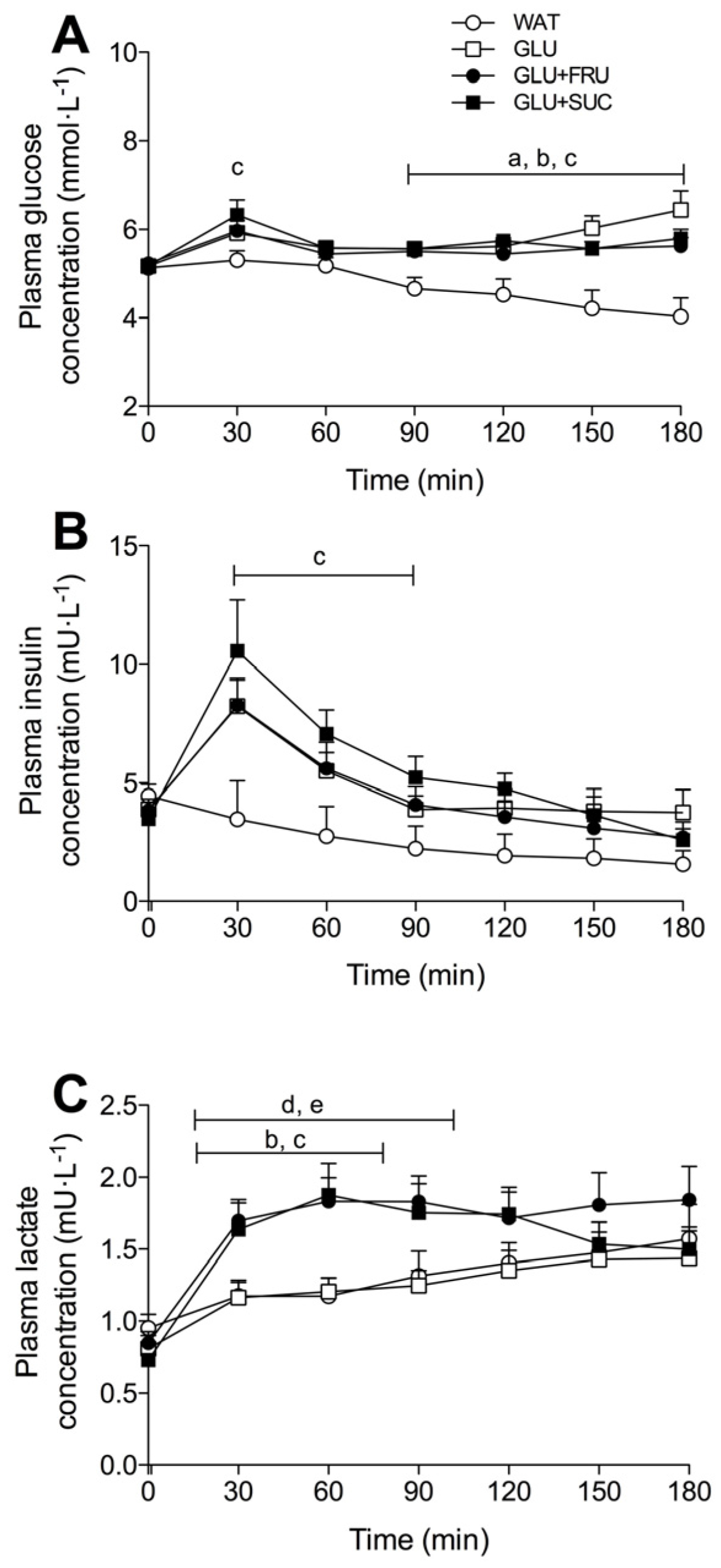

3.4. Plasma Metabolites

3.5. Gastrointestinal Distress and Rating of Percieved Exertion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coyle, E.F.; Coggan, A.R.; Hemmert, M.K.; Ivy, J.L. Muscle glycogen utilization during prolonged strenuous exercise when fed carbohydrate. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 1986, 61, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.W.; Zachwieja, J.J.; Peronnet, F.; Passe, D.H.; Massicotte, D.; Lavoie, C.; Pascoe, D.D. Fuel selection and cycling endurance performance with ingestion of [13C]glucose: Evidence for a carbohydrate dose response. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2010, 108, 1520–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellingwerff, T.; Cox, G.R. Systematic review: Carbohydrate supplementation on exercise performance or capacity of varying durations. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coggan, A.R.; Coyle, E.F. Reversal of fatigue during prolonged exercise by carbohydrate infusion or ingestion. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 1987, 63, 2388–2395. [Google Scholar]

- Jeukendrup, A.E.; Wagenmakers, A.J.; Stegen, J.H.; Gijsen, A.P.; Brouns, F.; Saris, W.H. Carbohydrate ingestion can completely suppress endogenous glucose production during exercise. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, E672–E683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeukendrup, A.E.; Jentjens, R. Oxidation of carbohydrate feedings during prolonged exercise: Current thoughts, guidelines and directions for future research. Sports Med. 2000, 29, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeukendrup, A.E. Carbohydrate and exercise performance: The role of multiple transportable carbohydrates. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2010, 13, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentjens, R.L.P.G.; Moseley, L.; Waring, R.H.; Harding, L.K.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Oxidation of combined ingestion of glucose and fructose during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2004, 96, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, R.E.; Leese, H.J. Sucrose absorption by the rat small intestine in vivo and in vitro. J. Physiol. 1977, 267, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraris, R.P.; Diamond, J. Regulation of intestinal sugar transport. Physiol. Rev. 1997, 77, 257–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sandle, G.I.; Lobley, R.W.; Warwick, R.; Holmes, R. Monosaccharide absorption and water secretion during disaccharide perfusion of the human jejunum. Digestion 1983, 26, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBosch, B.J.; Chi, M.; Moley, K.H. Glucose transporter 8 (GLUT8) regulates enterocyte fructose transport and global mammalian fructose utilization. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 4181–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leturque, A.; Brot-Laroche, E.; Le Gall, M.; Stolarczyk, E.; Tobin, V. The role of GLUT2 in dietary sugar handling. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2005, 61, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowlands, D.S.; Houltham, S.; Musa-Veloso, K.; Brown, F.; Paulionis, L.; Bailey, D. Fructose-Glucose Composite Carbohydrates and Endurance Performance: Critical Review and Future Perspectives. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1561–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Summers, R.W.; Schedl, H.P.; Flanagan, S.W.; Chang, R.; Gisolfi, C.V. Effects of carbohydrate type and concentration and solution osmolality on water absorption. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1995, 27, 1607–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, G.A.; Rowlands, D.S.; Shaw, C.; Jentjens, R.L.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Oxidation of Combined Ingestion of Maltodextrins and Fructose during Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, G.A.; Wittekind, A. Is there a specific role for sucrose in sports and exercise performance? Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2013, 23, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likely, R.; Johnson, E.; Ahearn, G.A. Functional characterization of a putative disaccharide membrane transporter in crustacean intestine. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2015, 185, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentjens, R.L.; Shaw, C.; Birtles, T.; Waring, R.H.; Harding, L.K.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Oxidation of combined ingestion of glucose and sucrose during exercise. Metabolism 2005, 54, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentjens, R.L.; Venables, M.C.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Oxidation of exogenous glucose, sucrose, and maltose during prolonged cycling exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2004, 96, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentjens, R.L.; Jeukendrup, A.E. High rates of exogenous carbohydrate oxidation from a mixture of glucose and fructose ingested during prolonged cycling exercise. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.D.; Tarpey, M.D.; Kass, L.S.; Tarpey, R.J.; Roberts, M.G. Assessing a commercially available sports drink on exogenous carbohydrate oxidation, fluid delivery and sustained exercise performance. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wijck, K.; Lenaerts, K.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Peters, W.H.M.; Buurman, W.A.; Dejong, C.H.C. Exercise-induced splanchnic hypoperfusion results in gut dysfunction in healthy men. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wijck, K.; Lenaerts, K.; Grootjans, J.; Wijnands, K.A.P.; Poeze, M.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Dejong, C.H.C.; Buurman, W.A. Physiology and pathophysiology of splanchnic hypoperfusion and intestinal injury during exercise: Strategies for evaluation and prevention. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G155–G168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.C.; Coatney, R.W. Nutrient-induced changes in intestinal blood flow in the dog. Br. Vet. J. 1994, 150, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilcore, D.; Nair, N.S.; Vanis, L.; Rayner, C.K.; Meyer, J.H.; Hausken, T.; Horowitz, M.; Jones, K.L. Comparative effects of oral and intraduodenal glucose on blood pressure, heart rate, and splanchnic blood flow in healthy older subjects. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 297, R716–R722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermak, N.M.; Gibala, M.J.; van Loon, L.J.C. Nitrate supplementation’s improvement of 10-km time-trial performance in trained cyclists. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2012, 22, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, G. Ratings of perceived exertion and heart rates during short-term cycle exercise and their use in a new cycling strength test. Int. J. Sports Med. 1982, 3, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wijck, K.; Wijnands, K.A.P.; Meesters, D.M.; Boonen, B.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Buurman, W.A.; Dejong, C.H.C.; Lenaerts, K.; Poeze, M. l-Citrulline Improves Splanchnic Perfusion and Reduces Gut Injury during Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 2039–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frayn, K.N. Calculation of substrate oxidation rates in vivo from gaseous exchange. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 1983, 55, 628–634. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, H. Isotopic standards for carbon and oxygen and correction factors for mass-spectrometric analysis of carbon dioxide. Geochim. Cosmoch. Acta 1957, 12, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnay, F.; Lacroix, M.; Mosora, F.; Luyckx, A.; Lefebvre, P. Glucose oxidation during prolonged exercise evaluated with naturally labeled [13C]glucose. J. Appl. Physiol. 1977, 43, 258–261. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, J.J.; Koziet, J.; Chauvet, D.; Darmaun, D.; Desjeux, J.F.; Young, V.R. Use of 13C-labeled glucose for estimating glucose oxidation: Some design considerations. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 1987, 63, 1725–1732. [Google Scholar]

- Pallikarakis, N.; Sphiris, N.; Lefebvre, P. Influence of the bicarbonate pool and on the occurrence of 13CO2 in exhaled air. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1991, 63, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenmakers, A.J.; Brouns, F.; Saris, W.H.; Halliday, D. Oxidation rates of orally ingested carbohydrates during prolonged exercise in men. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 1993, 75, 2774–2780. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands, D.S.; Wallis, G.A.; Shaw, C.; Jentjens, R.L.P.G.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Glucose polymer molecular weight does not affect exogenous carbohydrate oxidation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 1510–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentjens, R.L.; Achten, J.; Jeukendrup, A.E. High oxidation rates from combined carbohydrates ingested during exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughlin, M.R. Normal roles for dietary fructose in carbohydrate metabolism. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3117–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, J.T.; Fuchs, C.J.; Smith, F.E.; Thelwall, P.E.; Taylor, R.; Stevenson, E.J.; Trenell, M.I.; Cermak, N.M.; van Loon, L.J.C. Ingestion of glucose or sucrose prevents liver but not muscle glycogen depletion during prolonged endurance-type exercise in trained cyclists. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 309, E1032–E1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecoultre, V.; Benoit, R.; Carrel, G.; Schutz, Y.; Millet, G.P.; Tappy, L.; Schneiter, P. Fructose and glucose co-ingestion during prolonged exercise increases lactate and glucose fluxes and oxidation compared with an equimolar intake of glucose. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baur, D.A.; Schroer, A.B.; Luden, N.D.; Womack, C.J.; Smyth, S.A.; Saunders, M.J. Glucose-fructose enhances performance versus isocaloric, but not moderate, glucose. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 1778–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currell, K.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Superior endurance performance with ingestion of multiple transportable carbohydrates. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowlands, D.S.; Swift, M.; Ros, M.; Green, J.G. Composite versus single transportable carbohydrate solution enhances race and laboratory cycling performance. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 37, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, G.A.; Dubouchaud, H.; Brown, M.; Sicurello, J.P.; Butz, C.E. Role of mitochondrial lactate dehydrogenase and lactate oxidation in the intracellular lactate shuttle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappy, L.; Egli, L.; Lecoultre, V.; Schneider, P. Effects of fructose-containing caloric sweeteners on resting energy expenditure and energy efficiency: A review of human trials. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trommelen, J.; Fuchs, C.J.; Beelen, M.; Lenaerts, K.; Jeukendrup, A.E.; Cermak, N.M.; Van Loon, L.J.C. Fructose and Sucrose Intake Increase Exogenous Carbohydrate Oxidation during Exercise. Nutrients 2017, 9, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9020167

Trommelen J, Fuchs CJ, Beelen M, Lenaerts K, Jeukendrup AE, Cermak NM, Van Loon LJC. Fructose and Sucrose Intake Increase Exogenous Carbohydrate Oxidation during Exercise. Nutrients. 2017; 9(2):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9020167

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrommelen, Jorn, Cas J. Fuchs, Milou Beelen, Kaatje Lenaerts, Asker E. Jeukendrup, Naomi M. Cermak, and Luc J. C. Van Loon. 2017. "Fructose and Sucrose Intake Increase Exogenous Carbohydrate Oxidation during Exercise" Nutrients 9, no. 2: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9020167

APA StyleTrommelen, J., Fuchs, C. J., Beelen, M., Lenaerts, K., Jeukendrup, A. E., Cermak, N. M., & Van Loon, L. J. C. (2017). Fructose and Sucrose Intake Increase Exogenous Carbohydrate Oxidation during Exercise. Nutrients, 9(2), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9020167