Potential Health-modulating Effects of Isoflavones and Metabolites via Activation of PPAR and AhR

Abstract

1. Introduction

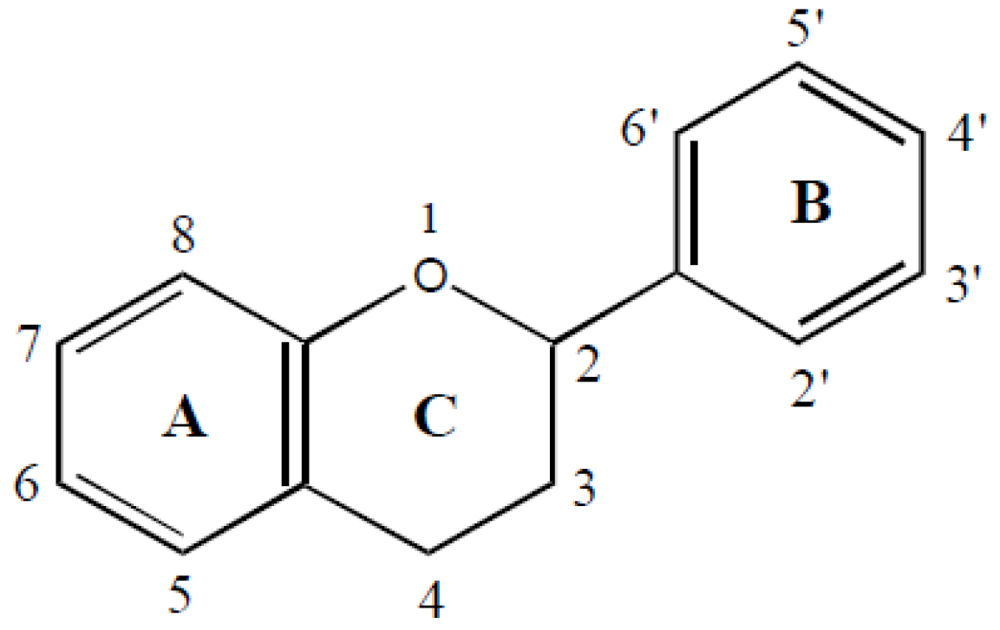

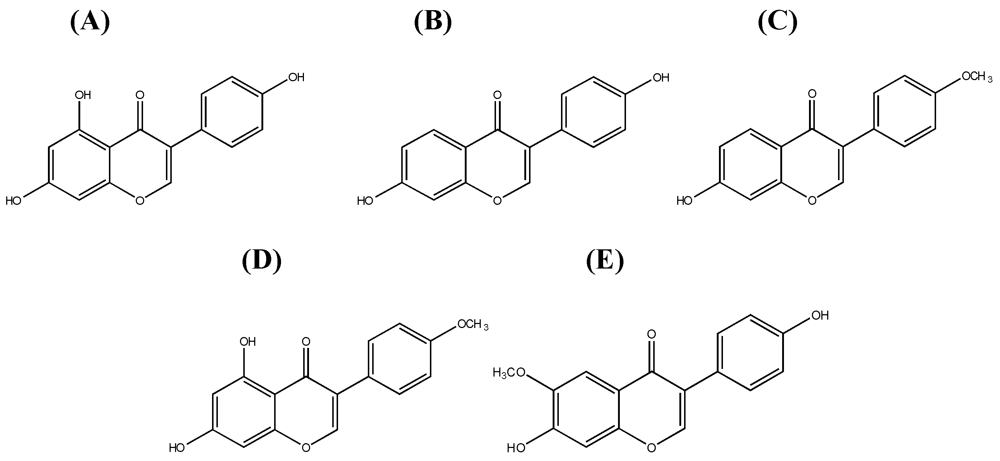

1.1. Systematics of Isoflavones

1.2. Dietary Sources and Intake of Isoflavones

1.3. Metabolism and Bioavailability of Isoflavones

1.4. Metabolic Diseases

1.4.1. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and γ

1.4.2. Inflammation and Atherosclerosis

1.4.3. PPAR Activation in in vitro Assays

| PPARα Transactivation | PPARγ Ligands | PPARγ Transactivation | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| biochanin A, genistein, daidzein, equol | [116] | ||

| genistein | genistein | [117] | |

| daidzein | daidzein | [118] | |

| genistein | [119] | ||

| daidzein | [120] | ||

| genistein, daidzein | genistein, daidzein | [121] | |

| biochanin A, genistein, daidzein, equol, ODMA, 6-hydroxydaidzein, 3´-hydroxygenistein, 6´-hydroxy-ODMA, angolensin, dihydrogenistein, dihydrobiochaninA, dihydroformononetin, dihydrodaidzein, p-ethylphenol | biochanin A, genistein, daidzein, equol, ODMA, 6-hydroxydaidzein, 3´-hydroxygenistein, 6´-hydroxy-ODMA, dihydrogenistein, dihydrodaidzein | [115] | |

| biochanin A, genistein, daidzein, ODMA, 6-hydroxydaidzein, 3´-hydroxygenistein | [114] | ||

| genistein, daidzein | genistein, daidzein, glycitein | [122] | |

| daidzein, equol | [123] | ||

| biochanin A, formononetin, genistein | biochanin A, genistein, daidzein | biochanin A, formononetin, genistein | [124] |

| Compounds | Cell line | Downregulated pro-inflammatory mediators | Upregulated anti-inflammatory mediators | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| genistein, equol | RAW 264.7 | NO, PGE2 | [136] | |

| genistein, | RAW 264.7 | TNFα, IL-6, iNOS, NFκB | IL-10 | [114] |

| daidzein, | TNFα, IL-6, iNOS, NFκB | |||

| formononetin | iNOS | |||

| biochanin A | TNFα, IL-6, iNOS, NFκB, Cox-2 | IL-10 | ||

| equol | TNFα, IL-6, COX-2 | |||

| ODMA | TNFα, IL-6 | |||

| genistein | HBMEC | TNFα, IL-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, IL-8, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 | [137] | |

| genistein, daidzein | murine J774 macrophages | iNOS, NO | [138] | |

| genistein | Human chondrocytes | COX-2, NO | [139] | |

| biochanin A | MC3T3-E1 cells | TNFα, IL-6, NO | [140] | |

| genistein | PBLs | TNFα, IL-8 | [141] | |

| genistein | mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures | TNFα, NO, superoxide | [142] | |

| daidzein, formononetin | mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures | TNFα, NO, superoxide | [143] | |

| biochanin A | mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures | TNFα, NO, superoxide | [144] | |

| genistein | alveolar macrophages | TNFα | [145] | |

| daidzein | PBMC | higher concentrations reduced IL-10 and IFN-γ levels | low concentration increased IL-2, IL-4,and IFN-γ | [146] |

| genistein | IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ mRNA and protein | |||

| genistein | RAW 264.7 | NO, PGE2 | [147] | |

| genistein | RAW 264.7 | PGE2, iNOS, COX-2 | [148] | |

| genistein, daidzein, glycetein | RAW 264.7 | NO, iNOS | [149] | |

| genistein, daidzein, equol | MCF-7 cells | COX-2 | [150] |

1.4.4. PPAR activation by isoflavones and its health effects

1.5. Xenobiotic Metabolism and Cell Cycle Control

1.5.1. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor

1.5.2. AhR in vitro assays

| Agonistic effects | Antagonistic effects | Assay | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dai(+)* | Dai(-), Gen(-) | Gel mobility shift assay (agonistic effects) | [220] |

| LBA (rat hepatic cytosol) (antagonistic effects) | |||

| Dai(-), Gen(+), Gly(-), Equ(+) | LBA (mammalian liver cell cytosol) | [218] | |

| Dai(+), Gen(+), Gly(+), Equ(-) | CALUX (mouse hepatoma cells) | [217] | |

| Gen(-) | LBA (rat hepatic cytosol) | [224] | |

| Dai(+)*,Gen (-) Dai(-),Gen (-) | SW-ELISA (Hepa-1c1c7) | [225] | |

| Dai(+)*,Gen (-) Dai(-),Gen (-) | CALUX (HepG2 cells) | ||

| Dai(+), Gen(+) | Transactivation assay (Hepa-1 cells) | [190] | |

| Dai(-), Gen(-) | Transactivation assay (HepG2 cells) | ||

| Dai(-), Gen(-) | Transactivation assay (MCF-7 cells) | ||

| Dai(-), Gen(-) | LBA (rat hepatic cytosol) | [191] | |

| Dai(+)*, Gen(+)* | Dai(+), Gen(+) | CYP1A1 expression in HepG2 cells | [226] |

| Bio(+) | Bio(+) | CYP1A1 expression in MCF-7 cells | [227] |

| LBA (rat hepatic cytosol) | |||

| Bio(+)* | Bio(+) | CALUX (MCF-7 cells) | [228] |

| CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 expression in MCF-7 cells | |||

| Bio(+)#, Dai(-), Equ(+)*, For(+)#, Gen(-) | Transactivation assay (yeast) | [189] |

1.5.3. Cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP1A1

1.5.4. Cell cycle control

| Effect on cell cycle(cell type) | Further effects | Tested isoflavone (concentration) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| G2/M arrest(colon cancer)a | Genistein (111 µM) | [258] | |

| G2/M arrest(prostate cancer)b | Concomitant decrease of cyclin B | Isoflavones from soybean cake; genistein most efficient (30–50 µM) | [259] |

| G2/M arrest(bladder cancer)c | Inhibition of cdc2 kinase activity | Genistein (37 or 185 µM) | [260] |

| Direct induction of apoptosis without alteration of cell cycle distribution | Daidzein (39.3 or 196.7 µM) and biochanin A (35.2 or 175.9 µM) | ||

| Suppression of tumor growth in vivo (xenograft model; mice) | Genistein and combined isoflavones | ||

| G2/M arrest(prostate cancer)d | Genistein (18.5–74 µM) | [261] | |

| G2/M arrest(breast cancer cells overexpressing Bcl-2)e1 | Genistein (50 µM) | [262] | |

| G0/G1 arrest(control breast cancer cells)e2 | Genistein (50 µM) | ||

| G2/M arrest(bladder cancer)f | Reduction of tumor volume in vivo (xenograft model; mice) | Genistein (50 µM) | [263] |

| G2/M arrest(androgen-insensitive prostate cancer)g1 | Induction of tumor suppressor gene expression (p21, p16) | Genistein (10 or 25 µM) | [264] |

| G0/G1 arrest(androgen-sensitive prostate cancer)g2 | Induction of apoptosis(only in androgen-insensitive cells) | Genistein (10 or 25 µM) | |

| G2/M arrest(liver cancer)h | Induction of tumor suppressor genes expression (p21),Accumulation of p53 protein | Genistein (37–111 µM) | [265] |

| G2/M arrest(leukemia cells)i | Stimulates Raf-1 activation, Decreases Akt activation, Induction of p21 and cyclin B expression, Induction of apoptosis | Genistein (10 or 25 µM) | [266] |

| G2/M arrest(prostate cancer)j | Increased p21 expression, Decreased cyclin B expression, Decreased NFκB activity | Genistein (15 or 30 µM) | [267] |

| G1 cell arrest(androgen-sensitive prostate cancer)k | Increased p27 and p21 expression | Genistein (≤20 µM) | [268] |

| Induction of apoptosis | Genistein (40–80 µM) | ||

| G2/M arrest(non-tumorigenic breast cells)l | Enhanced expression of p21 and p53, but not p27 | Genistein (30 µM) | [269] |

| G2/M arrest(prostate cancer)m | Genistein (20–100 µM) | [270] | |

| G2/M arrest(B cell leukemia)n | Decreased IL-10 secretion, Upregulation of IFNγ | Genistein (7.5–60 µM) | [271] |

| G2/M arrest(breast cancer)o | Increased cyclin B | Genistein (15 or 30 µM) | [272] |

| G2/M arrest(eye cancer; choroidal melanoma)p | Induction of p21, but not required for cell cycle arrest | Genistein (30 or 60 µM) | [273] |

| G2/M arrest(eye cancer; choroidal melanoma)q | Upregulation of CDK1 and p21, but no effect of CDK2 and p27 | Genistein (30 µM) | [274] |

| G1 cell arrest(eye cancer; choroidal melanoma)q | Upregulation of CDK2 and weakly p21 and p27 | Daidzein (150 µM) | |

| G2/M arrest(eye cancer; choroidalmelanoma)r | Impairment of CDK1 dephosphorylation, Weak accumulation of p53 protein | Genistein (60 µM) | [275] |

| G2/M arrest(metastatic melanoma)s | Genistein (60 µM) | [276] | |

| G2/M arrest(gastric cancer)t | Genistein (25 or 60 µM) | [277] | |

| G1 cell arrest(gastric cancer)t | Daidzein (25 or 60 µM) | ||

| G2/M arrest(metastatic melanoma)u | Genistein (60 µM) | [278] | |

| S phase arrest(metastatic melanoma)u | Daidzein (60 µM) | ||

| G0/G1 arrest(colon cancer)v | Biphasic effect on cell growth | Daidzein (5–100 µM) | [279] |

1.5.5. AhR activation by isoflavones and health effects

2. General Conclusion

References

- Haslam, E. Practical Polyphenolics: from Structure to Molecular Recognition and Physiological Action; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; Volume XV, p. 422. [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo, G.; Mascolo, N.; Izzo, A.A.; Capasso, F. Flavonoids: old and new aspects of a class of natural therapeutic drugs. Life Sci. 1999, 65, 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.; Dwyer, J. Flavonoids: Dietary occurrence and biochemical activity. Nutrition Res. 1998, 18, 1995–2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, W.; Adlercreutz, H. Overview of naturally occurring endocrine-active substances in the human diet in relation to human health. Nutrition 2000, 16, 654–658. [Google Scholar]

- Liggins, J.; Bluck, L.J.; Runswick, S.; Atkinson, C.; Coward, W.A.; Bingham, S.A. Daidzein and genistein content of fruits and nuts. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2000, 11, 326–331. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, J.T.; Goldin, B.R.; Saul, N.; Gualtieri, L.; Barakat, S.; Adlercreutz, H. Tofu and soy drinks contain phytoestrogens. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1994, 94, 739–743. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Albrecht, D.; Bomser, J.; Schwartz, S.J.; Vodovotz, Y. Isoflavone profile and biological activity of soy bread. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7611–7616. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D.B.; Bailey, V.; Lloyd, A.S. Determination of phytoestrogens in dietary supplements by LC-MS/MS. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2008, 25, 534–547. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, E.; Beck, V.; Medjakovic, S.; Mueller, M.; Jungbauer, A. Comparison of hormonal activity of isoflavone-containing supplements used to treat menopausal complaints. Menopause 2009, 16, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Arai, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Kimira, M.; Shimoi, K.; Mochizuki, R.; Kinae, N. Dietary intakes of flavonols, flavones and isoflavones by Japanese women and the inverse correlation between quercetin intake and plasma LDL cholesterol concentration. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 2243–2250. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.S.; Kwon, C.S. Estimated dietary isoflavone intake of Korean population based on national nutrition survey. Nutr. Res. 2001, 21, 947–953. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.A.; Wen, W.; Xiang, Y.B.; Barnes, S.; Liu, D.; Cai, Q.; Zheng, W.; Xiao, O.S. Assessment of dietary isoflavone intake among middle-aged Chinese men. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Sun, J.; Liu, C.; Zeng, Q.; Huang, J.; Yu, B.; Huo, J. Intake of soy foods and soy isoflavones by rural adult women in China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 13, 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Surh, J.; Kim, M.J.; Koh, E.; Kim, Y.K.L.; Kwon, H. Estimated intakes of isoflavones and coumestrol in Korean population. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 57, 325–344. [Google Scholar]

- Takata, Y.; Maskarinec, G.; Franke, A.; Nagata, C.; Shimizu, H. A comparison of dietary habits among women in Japan and Hawaii. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Wakai, K.; Egami, I.; Kato, K.; Kawamura, T.; Tamakoshi, A.; Lin, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Wada, M.; Ohno, Y. Dietary intake and sources of isoflavones among Japanese. Nutr. Cancer 1999, 33, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boker, L.K.; Van der Schouw, Y.T.; De Kleijn, M.J.J.; Jacques, P.F.; Grobbee, D.E.; Peeters, P.H.M. Intake of dietary phytoestrogens by Dutch women. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 1319. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, O.K.; Chung, S.J.; Song, W.O. Estimated dietary flavonoid intake and major food sources of U.S. adults. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Kleijn, M.J.J.; Van der Schouw, Y.T.; Wilson, P.W.F.; Adlercreutz, H.; Mazur, W.; Grobbee, D.E.; Jacques, P.F. Intake of dietary phytoestrogens is low in postmenopausal women in the United States: The framingham study. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1826. [Google Scholar]

- Horn-Ross, P.L.; John, E.M.; Canchola, A.J.; Stewart, S.L.; Lee, M.M. Phytoestrogen intake and endometrial cancer risk. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan, A.A.; Welch, A.A.; McTaggart, A.A.; Bhaniani, A.; Bingham, S.A. Intakes and sources of soya foods and isoflavones in a UK population cohort study (EPIC-Norfolk). Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Setchell, K.D.R.; Brown, N.M.; Zimmer-Nechemias, L.; Brashear, W.T.; Wolfe, B.E.; Kirschner, A.S.; Heubi, J.E. Evidence for lack of absorption of soy isoflavone glycosides in humans, supporting the crucial role of intestinal metabolism for bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Richelle, M.; Pridmore-Merten, S.; Bodenstab, S.; Enslen, M.; Offord, E.A. Hydrolysis of isoflavone glycosides to aglycones by beta-glycosidase does not alter plasma and urine isoflavone pharmacokinetics in postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 2587–2592. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, V.; Lee, S.O.; Murphy, P.A.; Hendrich, S.; Verbruggen, M.A. The apparent absorptions of isoflavone glucosides and aglucons are similar in women and are increased by rapid gut transit time and low fecal isoflavone degradation. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2534. [Google Scholar]

- Zubik, L.; Meydani, M. Bioavailability of soybean isoflavones from aglycone and glucoside forms in American women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Izumi, T.; Piskula, M.K.; Osawa, S.; Obata, A.; Tobe, K.; Saito, M.; Kataoka, S.; Kubota, Y.; Kikuchi, M. Soy isoflavone aglycones are absorbed faster and in higher amounts than their glucosides in humans. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1695–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, M.; Takayanagi, T.; Harada, K.; Sawada, S.; Ishikawa, F. Bioavailability of isoflavones after ingestion of soy beverages in healthy adults. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2291–2296. [Google Scholar]

- de Pascual-Teresa, S.; Hallund, J.; Talbot, D.; Schroot, J.; Williams, C.M.; Bugel, S.; Cassidy, A. Absorption of isoflavones in humans: effects of food matrix and processing. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006, 17, 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda, N.; Pomeroy, S.; Nestel, P. Absorption in humans of isoflavones from soy and red clover is similar. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 2199. [Google Scholar]

- Day, A.J.; Dupont, M.S.; Rhodes, M.J.C.; Morgan, M.R.A.; Williamson, G.; Ridley, S.; Rhodes, M. Deglycosylation of flavonoid and isoflavonoid glycosides by human small intestine and liver β-glucosidase activity. FEBS Lett. 1998, 436, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Akaza, H.; Miyanaga, N.; Takashima, N.; Naito, S.; Hirao, Y.; Tsukamoto, T.; Fujioka, T.; Mori, M.; Kim, W.J.; Song, J.M.; Pantuck, A.J. Comparisons of percent equol producers between prostate vancer patients and controls: Case-controlled studies of isoflavones in Japanese, Korean and American residents. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 34, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Akaza, H.; Miyanaga, N.; Takashima, N.; Naito, S.; Hirao, Y.; Tsukamoto, T.; Mori, M. Is daidzein non-metabolizer a high risk for prostate cancer? A case-controlled study of serum soybean isoflavone concentration. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 32, 296–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, D.; Sanders, K.; Kolybaba, M.; Lopez, D. Case-control study of phyto-oestrogens and breast cancer. Lancet 1997, 350, 990–994. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, A.M.; Merz-Demlow, B.E.; Xu, X.; Phipps, W.R.; Kurzer, M.S. Premenopausal equol excretors show plasma hormone profiles associated with lowered risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2000, 9, 581–586. [Google Scholar]

- Marugame, T.; Katanoda, K. International comparisons of cumulative risk of breast and prostate cancer, from Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Vol. VIII. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 36, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althuis, M.D.; Dozier, J.M.; Anderson, W.F.; Devesa, S.S.; Brinton, L.A. Global trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality 1973-1997. Intern. J. Epidem. 2005, 34, 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, C.; Kawakami, N.; Shimizu, H. Trends in the incidence rate and risk factors for breast cancer in Japan. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1997, 44, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.C.; Chang, C.J.; Hsu, C.; Cheng, C.C.; Chiu, C.F.; Cheng, A.L. Significant difference in the trends of female breast cancer incidence between Taiwanese and Caucasian Americans: implications from age-period-cohort analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14, 1986–1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, K.S.; Reilly, M.; Tan, C.S.; Lee, J.; Pawitan, Y.; Adami, H.O.; Hall, P.; Mow, B. Profound changes in breast cancer incidence may reflect changes into a Westernized lifestyle: a comparative population-based study in Singapore and Sweden. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 113, 302–306. [Google Scholar]

- Adlercreutz, H.; Honjo, H.; Higashi, A.; Fotsis, T.; Hamalainen, E.; Hasegawa, T.; Okada, H. Urinary excretion of lignans and isoflavonoid phytoestrogens in Japanese men and women consuming a traditional Japanese diet. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Blakesmith, S.J.; Samman, S.; Lyons-Wall, P.M.; Joannou, G.E.; Petocz, P. Urinary isoflavonoid excretion is inversely associated with the ratio of protein to dietary fibre intake in young women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 284. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M.C.; O'Brien, B.; McCormack, T. Equol producer status, salivary estradiol profile and urinary excretion of isoflavones in Irish Caucasian women, following ingestion of soymilk. Steroids 2007, 72, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedlund, T.E.; Maroni, P.D.; Ferucci, P.G.; Dayton, R.; Barnes, S.; Jones, K.; Moore, R.; Ogden, L.G.; Wähälä, K.; Sackett, H.M.; Gray, K.J. Long-term dietary habits affect soy isoflavone metabolism and accumulation in prostatic fluid in Caucasian men. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1400–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.J.W.; Anderson, K.E. Sex and long-term soy diets affect the metabolism and excretion of soy isoflavones in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 1500S–1504S. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, C.; Iwasa, S.; Shiraki, M.; Ueno, T.; Uchiyama, S.; Urata, K.; Sahashi, Y.; Shimizu, H. Associations among maternal soy intake, isoflavone levels in urine and blood samples, and maternal and umbilical hormone concentrations (Japan). CCC 2006, 17, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rafii, F.; Davis, C.; Park, M.; Heinze, T.M.; Beger, R.D. Variations in metabolism of the soy isoflavonoid daidzein by human intestinal microfloras from different individuals. Arch. Microbiol. 2003, 180, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Setchell, K.D.R.; Maynard Brown, N.; Zimmer-Nechimias, L.; Wolfe, B.; Creutzinger, V.; Heubi, J.E.; Desai, P.B.; Jakate, A.S. Bioavailability, disposition, and dose-response effects of soy isoflavones when consumed by healthy women at physiologically typical dietary intakes. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Song, K.B.; Atkinson, C.; Frankenfeld, C.L.; Jokela, T.; Wähälä, K.; Thomas, W.K.; Lampe, J.W. Prevalence of daidzein-metabolizing phenotypes differs between Caucasian and Korean American women and girls. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1347–1351. [Google Scholar]

- Todaka, E.; Sakurai, K.; Fukata, H.; Miyagawa, H.; Uzuki, M.; Omori, M.; Osada, H.; Ikezuki, Y.; Tsutsumi, O.; Iguchi, T.; Mori, C. Fetal exposure to phytoestrogens - The difference in phytoestrogen status between mother and fetus. Environ. Res. 2005, 99, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.S.; Kwak, H.S.; Lim, H.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kang, Y.S.; Choe, T.B.; Hur, H.G.; Han, K.O. Isoflavone metabolites and their in vitro dual functions: They can act as an estrogenic agonist or antagonist depending on the estrogen concentration. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 101, 246–253. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, A.; Hanley, B.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Isoflavones, lignans and stilbenes - Origins, metabolism and potential importance to human health. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, S.M.; Hoikkala, A.; Wähälä, K.; Adlercreutz, H. Metabolism of the soy isoflavones daidzein, genistein and glycitein in human subjects. Identification of new metabolites having an intact isoflavonoid skeleton. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003, 87, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joannou, G.E.; Kelly, G.E.; Reeder, A.Y.; Waring, M.; Nelson, C. A urinary profile study of dietary phytoestrogens. The identification and mode of metabolism of new isoflavonoids. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995, 54, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, T.; Price, W.E.; Astheimer, L. The key importance of soy isoflavone bioavailability to understanding health benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 538–552. [Google Scholar]

- Espin, J.C.; Garcia-Conesa, M.T.; Tomas-Barberan, F.A. Nutraceuticals: facts and fiction. Phytochemi. 2007, 68, 2986–3008. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, I.L.; Williamson, G. Review of the factors affecting bioavailability of soy isoflavones in humans. Nutr. Cancer 2007, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, A. Factors affecting the bioavailability of soy isoflavones in humans. J. AOAC Int. 2006, 89, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrich, S. Bioavailability of isoflavones. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed Life Sci. 2002, 777, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Fact sheet No. 317. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/index.html (accessed: July 8th, 2009).

- Hajer, G.R.; Van Haeften, T.W.; Visseren, F.L.J. Adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity, diabetes, and vascular diseases. Europ. Heart J. 2008, 29, 2959–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalesin, K.C.; Franklin, B.A.; Miller, W.M.; Peterson, E.D.; McCullough, P.A. Impact of Obesity on Cardiovascular Disease. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2008, 37, 663–684. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, G.; Zimmet, P.; Shaw, J.; Grundy, S.M. The IDF Consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. 2006. Available online: http://www.idf.org/home/index.cfm?node=1429 (accessed: July 8th,2009).

- Gurnell, M.; Chatterjee, V.K.K.; O'Rahilly, S.; Savage, D.B. The metabolic syndrome: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and its therapeutic modulation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 2412–2421. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, B.V.; Criqui, M.H.; Curb, J.D.; Rodabough, R.; Safford, M.M.; Santoro, N.; Wilson, A.C.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Risk factor clustering in the insulin resistance syndrome and its relationship to cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander women. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2003, 52, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lakka, H.-M.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Lakka, T.A.; Niskanen, L.K.; Kumpusalo, E.; Tuomilehto, J.; Salonen, J.T. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 288, 2709–2716. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, A.M.; Rosamond, W.D.; Girman, C.J.; Golden, S.H.; Schmidt, M.I.; East, H.E.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Heiss, G. The metabolic syndrome and 11-year risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Ridker, P.M.; Buring, J.E.; Cook, N.R.; Rifai, N. C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular events: an 8-year follow-up of 14 719 initially healthy American women. Circulation 2003, 107, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fain, J.N.; Madan, A.K.; Hiler, M.L.; Cheema, P.; Bahouth, S.W. Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Shargill, N.S.; Spiegelman, B.M. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: Direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 1993, 259, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmouni, K.; Mark, A.L.; Haynes, W.G.; Sigmund, C.D. Adipose depot-specific modulation of angiotensinogen gene expression in diet-induced obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2004, 286, E891–E895. [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura, I.; Funahashi, T.; Takahashi, M.; Maeda, K.; Kotani, K.; Nakamura, T.; Yamashita, S.; Miura, M.; Fukuda, Y.; Takemura, K.; Tokunaga, K.; Matsuzawa, Y. Enhanced expression of PAI-1 in visceral fat: Possible contributor to vascular disease in obesity. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 800–803. [Google Scholar]

- Combs, T.P.; Wagner, J.A.; Berger, J.; Doebber, T.; Wang, W.J.; Zhang, B.B.; Tanen, M.; Berg, A.H.; O'Rahilly, S.; Savage, D.B.; Chatterjee, K.; Weiss, S.; Larson, P.J.; Gottesdiener, K.M.; Gertz, B.J.; Charron, M.J.; Scherer, P.E.; Moller, D.E. Induction of adipocyte complement-related protein of 30 kilodaltons by PPARγ agonists: A potential mechanism of insulin sensitization. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 998–1007. [Google Scholar]

- You, T.; Nicklas, B.J.; Ding, J.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Bauer, D.C.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Harris, T.B.; Kritchevsky, S.B. The metabolic syndrome is associated with circulating adipokines in older adults across a wide range of adiposity. J. Gerontol.- Series A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008, 63, 414–419. [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Thummel, C.; Beato, M.; Herrlich, P.; Schütz, G.; Umesono, K.; Blumberg, B.; Kastner, P.; Mark, M.; Chambon, P.; Evans, R.M. The nuclear receptor super-family: The second decade. Cell 1995, 83, 835–839. [Google Scholar]

- Fajas, L.; Auboeuf, D.; Raspe, E.; Schoonjans, K.; Lefebvre, A.M.; Saladin, R.; Najib, J.; Laville, M.; Fruchart, J.C.; Deeb, S.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Flier, J.; Briggs, M.R.; Staels, B.; Vidal, H.; Auwerx, J. The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARgamma gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 18779–18789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Braissant, O.; Foufelle, F.; Scotto, C.; Dauca, M.; Wahli, W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): Tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology 1996, 137, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinetti, G.; Fruchart, J.C.; Staels, B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): Nuclear receptors at the crossroads between lipid metabolism and inflammation. Inflamm. Res. 2000, 49, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Chinetti, G.; Griglio, S.; Antonucci, M.; Torra, I.P.; Delerive, P.; Majd, Z.; Fruchart, J.C.; Chapman, J.; Najib, J.; Staels, B. Activation of proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma induces apoptosis of human monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 25573–25580. [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer, S.A.; Sundseth, S.S.; Jones, S.A.; Brown, P.J.; Wisely, G.B.; Koble, C.S.; Devchand, P.; Wahli, W.; Willson, T.M.; Lenhard, J.M.; Lehmann, J.M. Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and γ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94, 4318–4323. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.M.; Lenhard, J.M.; Oliver, B.B.; Ringold, G.M.; Kliewer, S.A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma are activated by indomethacin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 3406–3410. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, B.M.; Chen, J.; Evans, R.M. Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94, 4312–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, B.M.; Tontonoz, P.; Chen, J.; Brun, R.P.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Evans, R.M. 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPARgamma. Cell 1995, 83, 803–812. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.M.; Moore, L.B.; Smith-Oliver, T.A.; Wilkison, W.O.; Willson, T.M.; Kliewer, S.A. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma). J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 12953–12956. [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire, F.M.; Smas, C.M.; Sul, H.S. Understanding adipocyte differentiation. Physiol. Rev. 1998, 78, 783–809. [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz, P.; Hu, E.; Spiegelman, B.M. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPARgamma2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell 1994, 79, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Ting, A.T.; Seed, B. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature 1998, 391, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamon, J.; Waki, H.; Terauchi, Y.; Kubota, N.; Hara, K.; Mori, Y.; Ide, T.; Murakami, K.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Ezaki, O.; Akanuma, Y.; Gavrilova, O.; Vinson, C.; Reitman, M.L.; Kagechika, H.; Shudo, K.; Yoda, M.; Nakano, Y.; Tobe, K.; Nagai, R.; Kimura, S.; Tomita, M.; Froguel, P.; Kadowaki, T. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 941–946. [Google Scholar]

- Kallen, C.B.; Lazar, M.A. Antidiabetic thiazolidinediones inhibit leptin (ob) gene expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 5793–5796. [Google Scholar]

- Takata, Y.; Kitami, Y.; Yang, Z.H.; Nakamura, M.; Okura, T.; Hiwada, K. Vascular inflammation is negatively autoregulated by interaction between CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-δ and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Circ. Res. 2002, 91, 427–433. [Google Scholar]

- Steppan, C.M.; Bailey, S.T.; Bhat, S.; Brown, E.J.; Banerjee, R.R.; Wright, C.M.; Patel, H.R.; Ahima, R.S.; Lazar, M.A. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature 2001, 409, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Laplante, M.; Festuccia, W.T.; Soucy, G.; Gelinas, Y.; Lalonde, J.; Berger, J.P.; Deshaies, Y. Mechanisms of the depot specificity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma action on adipose tissue metabolism. Diabetes 2006, 55, 2771–2778. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, H.P.; Yong, L.; Jensen, M.V.; Newgard, C.B.; Steppan, C.M.; Lazar, M.A. A futile metabolic cycle activated in adipocytes by antidiabetic agents. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, B.L.; Hebbachi, A.; Hauton, D.; Brown, A.M.; Wiggins, D.; Patel, D.D.; Gibbons, G.F. A role for PPARalpha in the control of SREBP activity and lipid synthesis in the liver. Biochem. J. 2005, 389, 413–421. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka, T.; Shimano, H.; Yahagi, N.; Amemiya-Kudo, M.; Yoshikawa, T.; Hasty, A.H.; Tamura, Y.; Osuga, J.; Okazaki, H.; Iizuka, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Sone, H.; Gotoda, T.; Ishibashi, S.; Yamada, N. Dual regulation of mouse Delta(5)- and Delta(6)-desaturase gene expression by SREBP-1 and PPARalpha. J. Lipid Res. 2002, 43, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Desvergne, B.; Wahli, W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: nuclear control of metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 1999, 20, 649–688. [Google Scholar]

- Schoonjans, K.; Peinado-Onsurbe, J.; Lefebvre, A.M.; Heyman, R.A.; Briggs, M.; Deeb, S.; Staels, B.; Auwerx, J. PPARalpha and PPARgamma activators direct a distinct tissue-specific transcriptional response via a PPRE in the lipoprotein lipase gene. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 5336–5348. [Google Scholar]

- Staels, B.; Vu-Dac, N.; Kosykh, V.A.; Saladin, R.; Fruchart, J.C.; Dallongeville, J.; Auwerx, J. Fibrates downregulate apolipoprotein C-III expression independent of induction of peroxisomal acyl coenzyme A oxidase. A potential mechanism for the hypolipidemic action of fibrates. J. Clin. Invest. 1995, 95, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu-Dac, N.; Schoonjans, K.; Kosykh, V.; Dallongeville, J.; Fruchart, J.C.; Staels, B.; Auwerx, J. Fibrates increase human apolipoprotein A-II expression through activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. J. Clin. Invest. 1995, 96, 741–750. [Google Scholar]

- Vu-Dac, N.; Schoonjans, K.; Laine, B.; Fruchart, J.C.; Auwerx, J.; Staels, B. Negative regulation of the human apolipoprotein A-I promoter by fibrates can be attenuated by the interaction of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor with its response element. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 31012–31018. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, R. Atherosclerosis - An inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Davignon, J.; Ganz, P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation 2004, 109, III27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, G.; Bendszus, M. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: Novel insights into plaque formation and destabilization. Stroke 2006, 37, 1923–1932. [Google Scholar]

- Laine, P.; Kaartinen, M.; Penttila, A.; Panula, P.; Paavonen, T.; Kovanen, P.T. Association between myocardial infarction and the mast cells in the adventitia of the infarct-related coronary artery. Circulation 1999, 99, 361–369. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, P.K.; Falk, E.; Badimon, J.J.; Fernandez-Ortiz, A.; Mailhac, A.; Villareal-Levy, G.; Fallon, J.T.; Regnstrom, J.; Fuster, V. Human monocyte-derived macrophages induce collagen breakdown in fibrous caps of atherosclerotic plaques. Potential role of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases and implications for plaque rupture. Circulation 1995, 92, 1565–1569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fuster, V.; Moreno, P.R.; Fayad, Z.A.; Corti, R.; Badimon, J.J. Atherothrombosis and high-risk plaque: Part I: Evolving concepts. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 46, 937–954. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, N.; Duez, H.; Fruchart, J.C.; Staels, B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and atherogenesis: Regulators of gene expression in vascular cells. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Xu, H.; Pan, L.; Wen, J.; Liao, W.; Chen, K. Rosiglitazone promotes atherosclerotic plaque stability in fat-fed ApoE-knockout mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 590, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, N.; Sukhova, G.; Murphy, C.; Libby, P.; Plutzky, J. Macrophages in human atheroma contain PPARgamma: Differentiation-dependent peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) expression and reduction of MMP-9 activity through PPARgamma activation in mononuclear phagocytes in vitro. Am. J. Pathol. 1998, 153, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.C.; Binder, C.J.; Gutierrez, A.; Brown, K.K.; Plotkin, C.R.; Pattison, J.W.; Valledor, A.F.; Davis, R.A.; Willson, T.M.; Witztum, J.L.; Palinski, W.; Glass, C.K. Differential inhibition of macrophage foam-cell formation and atherosclerosis in mice by PPARalpha, beta/delta, and gamma. J. Clin. Invest. 2004, 114, 1564–1576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Lan, D.; Chen, W.; Matsuura, F.; Tall, A.R. ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cellular cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 9774–9779. [Google Scholar]

- Chinetti, G.; Lestavel, S.; Bocher, V.; Remaley, A.T.; Neve, B.; Torra, I.P.; Teissier, E.; Minnich, A.; Jaye, M.; Duverger, N.; Brewer, H.B.; Fruchart, J.C.; Clavey, V.; Staels, B. PPAR-alpha and PPAR-gamma activators induce cholesterol removal from human macrophage foam cells through stimulation of the ABCA1 pathway. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Souissi, I.J.; Billiet, L.; Cuaz-Perolin, C.; Slimane, M.N.; Rouis, M. Matrix metalloproteinase-12 gene regulation by a PPAR alpha agonist in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 3405–3414. [Google Scholar]

- Jeanpierre, E.; Le Tourneau, T.; Zawadzki, C.; Van Belle, E.; Mouquet, F.; Susen, S.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Staels, B.; Jude, B.; Corseaux, D. Beneficial effects of fenofibrate on plaque thrombogenicity and plaque stability in atherosclerotic rabbits. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2009, 18, 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, M.; Jungbauer, A. Red clover extract – a source for substances that activate PPARalpha and ameliorate cytokine secretion profile of LPS-stimulated macrophages. Menopause 2010. In press.. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, M.; Jungbauer, A. Red clover extract: A putative source for simultaneous treatment of menopausal disorders and the metabolic syndrome. Menopause 2008, 15, 1120–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Chacko, B.K.; Chandler, R.T.; D'Alessandro, T.L.; Mundhekar, A.; Khoo, N.K.H.; Botting, N.; Barnes, S.; Patel, R.P. Anti-inflammatory effects of isoflavones are dependent on flow and human endothelial cell PPARgamma. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Z.C.; Audinot, V.; Papapoulos, S.E.; Boutin, J.A.; Lowik, C.W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma ) as a molecular target for the soy phytoestrogen genistein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 962–967. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Z.; Löwik, C.W.G.M. The balance between concurrent activation of ERs and PPARs determines daidzein-induced osteogenesis and adipogenesis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 853–861. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Shin, H.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, M.O. Genistein enhances expression of genes involved in fatty acid catabolism through activation of PPARalpha. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2004, 220, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.I.; Vattem, D.A.; Shetty, K. Evaluation of clonal herbs of Lamiaceae species for management of diabetes and hypertension. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 15, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mezei, O.; Banz, W.J.; Steger, R.W.; Peluso, M.R.; Winters, T.A.; Shay, N. Soy isoflavones exert antidiabetic and hypolipidemic effects through the PPAR pathways in obese Zucker rats and murine RAW 264.7 cells. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ricketts, M.L.; Moore, D.D.; Banz, W.J.; Mezei, O.; Shay, N.F. Molecular mechanisms of action of the soy isoflavones includes activation of promiscuous nuclear receptors. A review. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2005, 16, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.W.; Lee, O.H.; Banz, W.J.; Moustaid-Moussa, N.; Shay, N.F.; Kim, Y.C. Daidzein and the daidzein metabolite, equol, enhance adipocyte differentiation and PPARgamma transcriptional activity. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009.

- Shen, P.; Liu, M.H.; Ng, T.Y.; Chan, Y.H.; Yong, E.L. Differential effects of isoflavones, from Astragalus Membranaceus and Pueraria Thomsonii, on the activation of PPARalpha, PPARgamma, and adipocyte differentiation in vitro. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yeh, W.C.; Cao, Z.; Classon, M.; McKnight, S.L. Cascade regulation of terminal adipocyte differentiation by three members of the C/EBP family of leucine zipper proteins. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 168–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.B.; Spiegelman, B.M. ADD1/SREBP1 promotes adipocyte differentiation and gene expression linked to fatty acid metabolism. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.T.; Lane, M.D. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha is sufficient to initiate the 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994, 91, 8757–8761. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J.; Della-Fera, M.A.; Hausman, D.B.; Rayalam, S.; Ambati, S.; Baile, C.A. Genistein inhibits differentiation of primary human adipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Phrakonkham, P.; Viengchareun, S.; Belloir, C.; Lombès, M.; Artur, Y.; Canivenc-Lavier, M.C. Dietary xenoestrogens differentially impair 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation and persistently affect leptin synthesis. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 110, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Ikeda, K.; Xu, J.W.; Yamori, Y.; Gao, X.M.; Zhang, B.L. Genistein suppresses adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells via multiple signal pathways. Phytotherapy Res. 2009, 23, 713–718. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Q.C.; Li, Y.L.; Qin, Y.F.; Quarles, L.D.; Xu, K.K.; Li, R.; Zhou, H.H.; Xiao, Z.S. Inhibition of adipocyte differentiation by phytoestrogen genistein through a potential downregulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 activity. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 104, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.T.; Park, I.J.; Shin, J.I.; Lee, Y.K.; Lee, S.K.; Baik, H.W.; Ha, J.; Park, O.J. Genistein, EGCG, and capsaicin inhibit adipocyte differentiation process via activating AMP-activated protein kinases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 338, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K.; Nelson-Dooley, C.; Della-Fera, M.A.; Yang, J.Y.; Zhang, W.; Duan, J.; Hartzell, D.L.; Hamrick, M.W.; Baile, C.A. Genistein decreases food intake, body weight, and fat pad weight and causes adipose tissue apoptosis in ovariectomized female mice. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hanada, T.; Yoshimura, A. Regulation of cytokine signaling and inflammation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002, 13, 413–421. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, S.S. NF-kappaB as a therapeutic target in chronic inflammation: recent advances. Mol. Med. Today 2000, 6, 441–448. [Google Scholar]

- Blay, M.; Espinel, A.E.; Delgado, M.A.; Baiges, I.; Bladé, C.; Arola, L.; Salvadó, J. Isoflavone effect on gene expression profile and biomarkers of inflammation. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010, 51, 382–390. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.W.; Lee, W.H. Protective effects of genistein on proinflammatory pathways in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2008, 19, 819–825. [Google Scholar]

- Hämäläinen, M.; Nieminen, R.; Vuorela, P.; Heinonen, M.; Moilanen, E. Anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids: Genistein, kaempferol, quercetin, and daidzein inhibit STAT-1 and NF-kB activations, whereas flavone, isorhamnetin, naringenin, and pelargonidin inhibit only NF-?B activation along with their inhibitory effect on iNOS expression and NO production in activated macrophages. Med. Inflamm. 2007, 2007, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hooshmand, S.; Soung, D.Y.; Lucas, E.A.; Madihally, S.V.; Levenson, C.W.; Arjmandi, B.H. Genistein reduces the production of proinflammatory molecules in human chondrocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2007, 18, 609–614. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.H.; Choi, E.M. Biochanin A stimulates osteoblastic differentiation and inhibits hydrogen peroxide-induced production of inflammatory mediators in MC3T3-E1 cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 1948–1953. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, N.; Porath, D.; Radspieler, A.; Schwager, J. Effects of resveratrol, piceatannol, triacetoxystilbene, and genistein on the inflammatory response of human peripheral blood leukocytes. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Ma, G.; Ye, M.; Lu, G. Genistein protects dopaminergic neurons by inhibiting microglial activation. NeuroReport 2005, 16, 267–270. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.Q.; Wang, X.J.; Jin, Z.Y.; Xu, X.M.; Zhao, J.W.; Xie, Z.J. Protective effect of isoflavones from Trifolium pratense on dopaminergic neurons. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 62, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.Q.; Jin, Z.Y.; Li, G.H. Biochanin A protects dopaminergic neurons against lipopolysaccharide-induced damage through inhibition of microglia activation and proinflammatory factors generation. Neurosci. Letters 2007, 417, 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, P.E.; Olmstead, L.E.; Howard-Carroll, A.E.; Dickens, G.R.; Goltz, M.L.; Courtney-Shapiro, C.; Fanti, P. In vitro and in vivo effects of genistein on murine alveolar macrophage TNFα production. Inflammation 1999, 23, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Y.C.; Wu, C.C.; Chan, K.C.; Lin, Y.G.; Liao, J.W.; Wang, M.F.; Chang, Y.H.; Jeng, K.C. Nanonized black soybean enhances immune response in senescence-accelerated mice. Intern. J. Nanomed. 2009, 4, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Dia, V.P.; Berhow, M.A.; De Mejia, E.G. Bowman-birk inhibitor and genistein among soy compounds that synergistically inhibit nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 pathways in lipopolysaccharide-induced macrophages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11707–11717. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.C.; Huang, Y.T.; Tsai, S.H.; Lin-Shiau, S.Y.; Chen, C.F.; Lin, J.K. Suppression of inducible cyclooxygenase and inducible nitric oxide synthase by apigenin and related flavonoids in mouse macrophages. Carcinogenesis 1999, 20, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Sheu, F.; Lai, H.H.; Yen, G.C. Suppression effect of soy isoflavones on nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 Macrophages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1767–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, T.Y.; Leung, L.K. Soya isoflavones suppress phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced COX-2 expression in MCF-7 cells. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bitto, A.; Altavilla, D.; Bonaiuto, A.; Polito, F.; Minutoli, L.; Di Stefano, V.; Giuliani, D.; Guarini, S.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F. Effects of aglycone genistein in a rat experimental model of postmenopausal metabolic syndrome. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 200, 367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.M.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, M.H.; Jung, M.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Song, J. Effects of dietary genistein on hepatic lipid metabolism and mitochondrial function in mice fed high-fat diets. Nutrition 2006, 22, 956–964. [Google Scholar]

- Ae Park, S.; Choi, M.S.; Cho, S.Y.; Seo, J.S.; Jung, U.J.; Kim, M.J.; Sung, M.K.; Park, Y.B.; Lee, M.K. Genistein and daidzein modulate hepatic glucose and lipid regulating enzyme activities in C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. Life Sci. 2006, 79, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Jayagopal, V.; Albertazzi, P.; Kilpatrick, E.S.; Howarth, E.M.; Jennings, P.E.; Hepburn, D.A.; Atkin, S.L. Beneficial effects of soy phytoestrogen intake in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1709–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, T.; Uesugi, T.; Toda, T.; Miura, Y.; Yagasaki, K. Hypolipidemic action of the soybean isoflavones genistein and genistin in glomerulonephritic rats. Lipids 2002, 37, 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Roghani, M. Chronic administration of genistein improves aortic reactivity of streptozotocin-diabetic rats: Mode of action. Vascular Pharm. 2008, 49, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.S.; Kwon, S.J.; Na, S.Y.; Lim, S.P.; Lee, J.H. Genistein supplementation inhibits atherosclerosis with stabilization of the lesions in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2004, 19, 656–661. [Google Scholar]

- Asgary, S.; Moshtaghian, J.; Naderi, G.; Fatahi, Z.; Hosseini, M.; Dashti, G.; Adibi, S. Effects of dietary red clover on blood factors and cardiovascular fatty streak formation in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 768–770. [Google Scholar]

- Yamakoshi, J.; Piskula, M.K.; Izumi, T.; Tobe, K.; Saito, M.; Kataoka, S.; Obata, A.; Kikuchi, M. Isoflavone aglycone-rich extract without soy protein attenuates atherosclerosis development in cholesterol-fed rabbits. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1887–1893. [Google Scholar]

- Howes, J.B.; Tran, D.; Brillante, D.; Howes, L.G. Effects of dietary supplementation with isoflavones from red clover on ambulatory blood pressure and endothelial function in postmenopausal type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2003, 5, 325–332. [Google Scholar]

- Howes, J.B.; Sullivan, D.; Lai, N.; Nestel, P.; Pomeroy, S.; West, L.; Eden, J.A.; Howes, L.G. The effects of dietary supplementation with isoflavones from red clover on the lipoprotein profiles of post menopausal women with mild to moderate hypercholesterolaemia. Atherosclerosis 2000, 152, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lissin, L.W.; Oka, R.; Lakshmi, S.; Cooke, J.P. Isoflavones improve vascular reactivity in post-menopausal women with hypercholesterolemia. Vasc. Med. 2004, 9, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Taku, K.; Umegaki, K.; Sato, Y.; Taki, Y.; Endoh, K.; Watanabe, S. Soy isoflavones lower serum total and LDL cholesterol in humans: a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.; Higginbotham, A.; O'Connor, T.; Moustaid-Moussa, N.; Tebbe, A.; Kim, Y.C.; Cho, K.W.; Shay, N.; Adler, S.; Peterson, R.; Banz, W. Soy protein and isoflavones influence adiposity and development of metabolic syndrome in the obese male ZDF rat. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 51, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, L.A.; Chedraui, P.A.; Morocho, N.; Ross, S.; San Miguel, G. The effect of red clover isoflavones on menopausal symptoms, lipids and vaginal cytology in menopausal women: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2005, 21, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Sohn, I.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, Y.S. Hepatic gene expression profiles are altered by genistein supplementation in mice with diet-induced obesity. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, T.H.; Wu, W.M.; Hung, C.F.; Wu, W.B.; Chen, B.H. Anti-inflammatory effects of isoflavone powder produced from soybean cake. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 11068–11079. [Google Scholar]

- Fanti, P.; Asmis, R.; Stephenson, T.J.; Sawaya, B.P.; Franke, A.A. Positive effect of dietary soy in ESRD patients with systemic inflammation--correlation between blood levels of the soy isoflavones and the acute-phase reactants. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2006, 21, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar]

- Seibel, J.; Molzberger, A.F.; Hertrampf, T.; Laudenbach-Leschowski, U.; Diel, P. Oral treatment with genistein reduces the expression of molecular and biochemical markers of inflammation in a rat model of chronic TNBS-induced colitis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2009, 48, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, S.; He, D.; Zhao, S.; Liu, S. Genistein modulate immune responses in collagen-induced rheumatoid arthritis model. Maturitas 2008, 59, 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Verdrengh, M.; Jonsson, I.M.; Holmdahl, R.; Tarkowski, A. Genistein as an anti-inflammatory agent. Inflamm.n Res. 2003, 52, 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Kalhan, R.; Smith, L.J.; Nlend, M.C.; Nair, A.; Hixon, J.L.; Sporn, P.H.S. A mechanism of benefit of soy genistein in asthma: Inhibition of eosinophil p38-dependent leukotriene synthesis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2008, 38, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bloedon, L.T.; Jeffcoat, A.R.; Lopaczynski, W.; Schell, M.J.; Black, T.M.; Dix, K.J.; Thomas, B.F.; Albright, C.; Busby, M.G.; Crowell, J.A.; Zeisel, S.H. Safety and pharmacokinetics of purified soy isoflavones: single-dose administration to postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Adlercreutz, H.; Markkanen, H.; Watanabe, S. Plasma concentrations of phyto-oestrogens in Japanese men. Lancet 1993, 342, 1209–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Shimba, S.; Wada, T.; Tezuka, M. Arylhydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is involved in negative regulation of adipose differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells: AhR inhibits adipose differentiation independently of dioxin. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 2809–2817. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, D.; Qin, C.; Smith, R., 3rd; Safe, S. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated inhibition of LNCaP prostate cancer cell growth and hormone-induced transactivation. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 88, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safe, S.; Wormke, M. Inhibitory aryl hydrocarbon receptor-estrogen receptor α cross-talk and mechanisms of action. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003, 16, 807–816. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, M.E.; Karchner, S.I.; Shapiro, M.A.; Perera, S.A. Molecular evolution of two vertebrate aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptors (AHR1 and AHR2) and the PAS family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94, 13743. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Iii, C.A. Expression of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex in yeast. Activation of transcription by indole compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 32824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidel, S.D.; Winters, G.M.; Rogers, W.J.; Ziccardi, M.H.; Li, V.; Keser, B.; Denison, M.S. Activation of the Ah receptor signaling pathway by prostaglandins. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2001, 15, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Schaldach, C.M.; Riby, J.; Bjeldanes, L.F. Lipoxin A4: a new class of ligand for the Ah receptor. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 7594–7600. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, D.; Winter, G.M.; Rogers, W.J.; Lam, J.C.; Denison, M.S. Activation of the Ah receptor signal transduction pathway by bilirubin and biliverdin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 357, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara, K.; Kitamura, S.; Yamada, T.; Okayama, T.; Ohta, S.; Yamashita, K.; Yasuda, M.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Saeki, K.; Matsui, S.; Matsuda, T. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated induction of microsomal drug-metabolizing enzyme activity by indirubin and indigo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 318, 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi, J.; Mori, Y.; Matsui, S.; Takigami, H.; Fujino, J.; Kitagawa, H.; Matsuda, T.; Miller Iii, C.A.; Kato, T.; Saeki, K. Indirubin and Indigo are Potent Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Ligands Present in Human Urine. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 31475. [Google Scholar]

- Oesch-Bartlomowicz, B.; Huelster, A.; Wiss, O.; Antoniou-Lipfert, P.; Dietrich, C.; Arand, M.; Weiss, C.; Bockamp, E.; Oesch, F. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation by cAMP vs. dioxin: Divergent signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 9218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jinno, A.; Maruyama, Y.; Ishizuka, M.; Kazusaka, A.; Nakamura, A.; Fujita, S. Induction of cytochrome P450-1A by the equine estrogen equilenin, a new endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 98, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.D.; Bergander, L.; Rannug, U.; Rannug, A. Regulation of CYP1A1 transcription via the metabolism of the tryptophan-derived 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 383, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pohjanvirta, R.; Korkalainen, M.; McGuire, J.; Simanainen, U.; Juvonen, R.; Tuomisto, J.T.; Unkila, M.; Viluksela, M.; Bergman, J.; Poellinger, L.; Tuomisto, J. Comparison of acute toxicities of indolo[3,2-b]carbazole (ICZ) and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in TCDD-sensitive rats. Food. Chem. Toxicol. 2002, 40, 1023. [Google Scholar]

- Medjakovic, S.; Jungbauer, A. Red clover isoflavones biochanin A and formononetin are potent ligands of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 108, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Qin, C.; Safe, S.H. Flavonoids as aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists/antagonists: Effects of structure and cell context. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1877. [Google Scholar]

- Ashida, H. Suppressive effects of flavonoids on dioxin toxicity. BioFactors 2000, 12, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Iii, C.A. A human aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway constructed in yeast displays additive responses to ligand mixtures. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1999, 160, 297. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Bunce, N.J. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers as Ah receptor agonists and antagonists. Toxicol. Sci. 2003, 76, 310–320. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Bunce, N.J. Interaction between halogenated aromatic compounds in the Ah receptor signal transduction pathway. Environ. Toxicol. 2004, 19, 480–489. [Google Scholar]

- Poland, A.; Glover, E.; Kende, A.S. Stereospecific, high affinity binding of 2,3,7,8 tetrachlorodibenzo p dioxin by hepatic cytosol. Evidence that the binding species is receptor for induction of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 4936–4946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mukai, M.; Tischkau, S.A. Effects of tryptophan photoproducts in the circadian timing system: searching for a physiological role for aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 95, 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Heath-Pagliuso, S.; Rogers, W.J.; Tullis, K.; Seidel, S.D.; Denison, M.S.; Cenijn, P.H.; Brouwer, A. Activation of the Ah receptor by tryptophan and tryptophan metabolites. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 11508. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, B.J.; Bradfield, C.A. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is activated by modified low-density lipoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 1412–1417. [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich, F.P.; Martin, M.V.; McCormick, W.A.; Nguyen, L.P.; Glover, E.; Bradfield, C.A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor response to indigoids in vitro and in vivo. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 423, 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, E.C.; Bemis, J.C.; Henry, O.; Kende, A.S.; Gasiewicz, T.A. A potential endogenous ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor has potent agonist activity in vitro and in vivo. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 450, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Clagett-Dame, M.; Peterson, R.E.; Hahn, M.E.; Westler, W.M.; Sicinski, R.R.; DeLuca, H.F. A ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor isolated from lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 14694. [Google Scholar]

- Savouret, J.F.; Antenos, M.; Quesne, M.; Xu, J.; Milgrom, E.; Casper, R.F. 7-ketocholesterol is an endogenous modulator for the arylhydrocarbon receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 3054–3059. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.M.; Huang, D.Y.; Liu, G.F.; Zhong, J.C.; Du, K.; Li, Y.F.; Song, X.H. Inhibitory effects of vitamin A on TCDD-induced cytochrome P-450 1A1 enzyme activity and expression. Toxicol. Sci. 2005, 85, 727–734. [Google Scholar]

- Nebert, D.W.; Karp, C.L. Endogenous functions of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR): intersection of cytochrome P450 1 (CYP1)-metabolized eicosanoids and AHR biology. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 36061–36065. [Google Scholar]

- Schlecht, C.; Klammer, H.; Jarry, H.; Wuttke, W. Effects of estradiol, benzophenone-2 and benzophenone-3 on the expression pattern of the estrogen receptors (ER) alpha and beta, the estrogen receptor-related receptor 1 (ERR1) and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in adult ovariectomized rats. Toxicology 2004, 205, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.J.; Van Overmeire, I.; Goeyens, L.; Denison, M.S.; De Vito, M.J.; Clark, G.C. Analysis of Ah receptor pathway activation by brominated flame retardants. Chemosphere 2004, 55, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Saeki, K.I.; Kato, T.A.; Yamada, K.; Mizutani, T.; Miyata, N.; Matsuda, T.; Matsui, S.; Fukuhara, K. Activation of the human Ah receptor by aza-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their halogenated derivatives. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 26, 448. [Google Scholar]

- Abnet, C.C.; Tanguay, R.L.; Heideman, W.; Peterson, R.E. Transactivation activity of human, zebrafish, and rainbow trout aryl hydrocarbon receptors expressed in COS-7 cells: greater insight into species differences in toxic potency of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin, dibenzofuran, and biphenyl congeners. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1999, 159, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Till, M.; Riebniger, D.; Schmitz, H.J.; Schrenk, D. Potency of various polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as inducers of CYP1A1 in rat hepatocyte cultures. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1999, 117, 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Safe, S.; Wang, F.; Porter, W.; Duan, R.; McDougal, A. Ah receptor agonists as endocrine disruptors: Antiestrogenic activity and mechanisms. Toxicol. Lett. 1998, 102-103, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharat, I.; Saatcioglu, F. Antiestrogenic effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin are mediated by direct transcriptional interference with the liganded estrogen receptor: Cross-talk between aryl hydrocarbon- and estrogen-mediated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 10533–10537. [Google Scholar]

- Navas, J.M.; Segner, H. Antiestrogenicity of beta-naphthoflavone and PAHs in cultured rainbow trout hepatocytes: evidence for a role of the arylhydrocarbon receptor. Aquat. Toxicol. 2000, 51, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, O.; Oishi, S.; Yoneyama, M.; Ogata, A.; Kamimura, H. Antiestrogenic effect of paradichlorobenzene in immature mice and rats. Arch. Toxicol. 2007, 81, 505–517. [Google Scholar]

- Swedenborg, E.; Ruegg, J.; Makela, S.; Pongratz, I. Endocrine disruptive chemicals: mechanisms of action and involvement in metabolic disorders. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- McDougal, A.; Gupta, M.S.; Morrow, D.; Ramamoorthy, K.; Lee, J.E.; Safe, S.H. Methyl-substituted diindolylmethanes as inhibitors of estrogen-induced growth of T47D cells and mammary tumors in rats. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2001, 66, 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Safe, S.; Qin, C.; McDougal, A. Development of selective aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulators for treatment of breast cancer. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 1999, 8, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Amakura, Y.; Tsutsumi, T.; Sasaki, K.; Maitani, T.; Nakamura, M.; Kitagawa, H.; Fujino, J.; Toyoda, M.; Yoshida, T. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by some vegetable constituents determined using in vitro reporter gene assay. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 26, 532. [Google Scholar]

- Amakura, Y.; Tsutsumi, T.; Sasaki, K.; Maitani, T.; Yoshida, T. Screening of the inhibitory effect of vegetable constituents on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated activity induced by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p- dioxin. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 26, 1754. [Google Scholar]

- Amakura, Y.; Tsutsumi, T.; Sasaki, K.; Nakamura, M.; Yoshida, T.; Maitani, T. Influence of food polyphenols on aryl hydrocarbon receptor-signaling pathway estimated by in vitro bioassay. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 3117–3130. [Google Scholar]

- Ashida, H.; Fukuda, I.; Yamashita, T.; Kanazawa, K. Flavones and flavonols at dietary levels inhibit a transformation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor induced by dioxin. FEBS Lett. 2000, 476, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, I.; Sakane, I.; Yabushita, Y.; Sawamura, S.; Kanazawa, K.; Ashida, H. Black tea extract suppresses transformation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor induced by dioxin. BioFactors 2004, 21, 367. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, I.; Yabushita, Y.; Kodoi, R.; Nishiumi, S.; Kanazawa, K.; Ashida, H.; Sakane, I.; Kakuda, T.; Sawamura, S.I. Pigments in Green Tea Leaves (Camellia sinensis) Suppress Transformation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Induced by Dioxin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 2499. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiumi, S.; Hosokawa, K.; Mukai, R.; Fukuda, I.; Hishida, A.; Iida, O.; Yoshida, K.; Ashida, H. Screening of indigenous plants from Japan for modulating effects on transformation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2006, 7, 208–220. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, I.; Mukai, R.; Kawase, M.; Yoshida, K.i.; Ashida, H. Interaction between the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its antagonists, flavonoids. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 359, 822–827. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, M.; Satsu, H.; Natsume, Y.; Nishiumi, S.; Fukuda, I.; Ashida, H.; Shimizu, M. TCDD-induced CYP1A1 expression, an index of dioxin toxicity, is suppressed by flavonoids permeating the human intestinal Caco-2 cell monolayers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8891–8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shertzer, H.G.; Puga, A.; Chang, C.; Smith, P.; Nebert, D.W.; Setchell, K.D.; Dalton, T.P. Inhibition of CYP1A1 enzyme activity in mouse hepatoma cell culture by soybean isoflavones. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1999, 123, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Han, E.H.; Ji, Y.K.; Hye, G.J. Effect of biochanin A on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and cytochrome P450 1A1 in MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2006, 29, 570–576. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, H.Y.; Wang, H.; Leung, L.K. The red clover (Trifolium pratense) isoflavone biochanin A modulates the biotransformation pathways of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 90, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, E.C.; Rucci, G.; Gasiewicz, T.A. Characterization of multiple forms of the Ah receptor: comparison of species and tissues. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 6430–6440. [Google Scholar]

- Bergander, L.; Wincent, E.; Rannug, A.; Foroozesh, M.; Alworth, W.; Rannug, U. Metabolic fate of the Ah receptor ligand 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2004, 149, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Nebert, D.W.; Petersen, D.D.; Fornace, A.J., Jr. Cellular responses to oxidative stress: the [Ah] gene battery as a paradigm. Environ. Health Perspect. 1990, 88, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, S.P.; Wang, F.; Saarikoski, S.T.; Taylor, R.T.; Chapman, B.; Zhang, R.; Hankinson, O. A novel promoter element containing multiple overlapping xenobiotic and hypoxia response elements mediates induction of cytochrome P4502S1 by both dioxin and hypoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 10881–10893. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, T.P.; Dieter, M.Z.; Matlib, R.S.; Childs, N.L.; Shertzer, H.G.; Genter, M.B.; Nebert, D.W. Targeted knockout of Cyp1a1 gene does not alter hepatic constitutive expression of other genes in the mouse [Ah] battery. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 267, 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Uno, S.; Dalton, T.P.; Derkenne, S.; Curran, C.P.; Miller, M.L.; Shertzer, H.G.; Nebert, D.W. Oral exposure to benzo[a]pyrene in the mouse: detoxication by inducible cytochrome P450 is more important than metabolic activation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004, 65, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Nowack, R. Review article: cytochrome P450 enzyme, and transport protein mediated herb-drug interactions in renal transplant patients: grapefruit juice, St John's Wort - and beyond! Nephrology (Carlton) 2008, 13, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backlund, M.; Johansson, I.; Mkrtchian, S.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Signal transduction-mediated activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in rat hepatoma H4IIE cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 31755–31763. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, H.Y.; Leung, L.K. A potential protective mechanism of soya isoflavones against 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene tumour initiation. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 90, 457–465. [Google Scholar]

- Kasai, A.; Hiramatsu, N.; Hayakawa, K.; Yao, J.; Kitamura, M. Blockade of the dioxin pathway by herbal medicine Formula Bupleuri Minor: identification of active entities for suppression of AhR activation. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 838–846. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, H.; Hossain, A. Signal transduction-mediated CYP1A1 induction by omeprazole in human HepG2 cells. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 1999, 51, 342–346. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, G.; Modi, D.R.; Singh, M.P. The involvement of secondary signaling molecules in cytochrome P-450 1A1-mediated inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in benzo(a)pyrene-treated rat polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Life Sci. 2007, 81, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire, G.; Delescluse, C.; Pralavorio, M.; Ledirac, N.; Lesca, P.; Rahmani, R. The role of protein tyrosine kinases in CYP1A1 induction by omeprazole and thiabendazole in rat hepatocytes. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 2265–2278. [Google Scholar]

- Helsby, N.A.; Williams, J.; Kerr, D.; Gescher, A.; Chipman, J.K. The isoflavones equol and genistein do not induce xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes in mouse and in human cells. Xenobiotica 1997, 27, 587–596. [Google Scholar]

- Kishida, T.; Nagamoto, M.; Ohtsu, Y.; Watakabe, M.; Ohshima, D.; Nashiki, K.; Mizushige, T.; Izumi, T.; Obata, A.; Ebihara, K. Lack of an inducible effect of dietary soy isoflavones on the mRNA abundance of hepatic cytochrome P-450 isozymes in rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004, 68, 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Helsby, N.A.; Chipman, J.K.; Gescher, A.; Kerr, D. Inhibition of mouse and human CYP 1A- and 2E1-dependent substrate metabolism by the isoflavonoids genistein and equol. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1998, 36, 375–382. [Google Scholar]

- Shon, Y.H.; Park, S.D.; Nam, K.S. Effective chemopreventive activity of genistein against human breast cancer cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 39, 448–451. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.J.; Kim, T. Daidzein modulates induction of hepatic CYP1A1, 1B1, and AhR by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene in mice. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2008, 31, 1115–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, L.M.; Durant, P.; Leone-Kabler, S.; Wood, C.E.; Register, T.C.; Townsend, A.; Cline, J.M. Effects of prior oral contraceptive use and soy isoflavonoids on estrogen-metabolizing cytochrome P450 enzymes. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 112, 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Spink, D.C.; Spink, B.C.; Cao, J.Q.; DePasquale, J.A.; Pentecost, B.T.; Fasco, M.J.; Li, Y.; Sutter, T.R. Differential expression of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 in human breast epithelial cells and breast tumor cells. Carcinogenesis 1998, 19, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, P.H.; Lin, Y.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Hou, H.H.; Hsu, S.P.; Juan, S.H. Molecular mechanisms of p21 and p27 induction by 3-methylcholanthrene, an aryl-hydrocarbon receptor agonist, involved in antiproliferation of human umbilical vascular endothelial cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2008, 215, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Zhang, L.; Hoagland, M.S.; Swanson, H.I. Lack of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor leads to impaired activation of AKT/protein kinase B and enhanced sensitivity to apoptosis induced via the intrinsic pathway. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 320, 448–457. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, W.R.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, J.E.; Hong, Y.P.; Chun, Y.J.; Park, Y.C.; Oh, S.; Yoo, K.S.; Yoo, Y.H.; Kim, J.M. Abundance of aryl hydrocarbon receptor potentiates benzo[a]pyrene-induced apoptosis in Hepa1c1c7 cells via CYP1A1 activation. Toxicology 2007, 235, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, M.C.; Lapierre, I.; Brault, K.; Raymond, M. Aromatic hydrocarbon receptor (AhR).AhR nuclear translocator- and p53-mediated induction of the murine multidrug resistance mdr1 gene by 3-methylcholanthrene and benzo(a)pyrene in hepatoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 4819–4827. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schreck, I.; Chudziak, D.; Schneider, S.; Seidel, A.; Platt, K.L.; Oesch, F.; Weiss, C. Influence of aryl hydrocarbon- (Ah) receptor and genotoxins on DNA repair gene expression and cell survival of mouse hepatoma cells. Toxicology 2009, 259, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pru, J.K.; Kaneko-Tarui, T.; Jurisicova, A.; Kashiwagi, A.; Selesniemi, K.; Tilly, J.L. Induction of proapoptotic gene expression and recruitment of p53 herald ovarian follicle loss caused by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Reprod. Sci. 2009, 16, 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.D.; Murray, I.A.; Flaveny, C.A.; Kusnadi, A.; Perdew, G.H. Ah receptor represses acute-phase response gene expression without binding to its cognate response element. Lab. Invest. 2009, 89, 695–707. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Jarrard, D.F.; Bjorling, D.E. Roles of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in modulating urothelial cell proliferation. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2008, 15, 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Fu, M.; D'Amico, M.; Albanese, C.; Zhou, J.N.; Brownlee, M.; Lisanti, M.P.; Chatterjee, V.K.; Lazar, M.A.; Pestell, R.G. Inhibition of cellular proliferation through IkappaB kinase-independent and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-dependent repression of cyclin D1. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 3057–3070. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.C.; Donovan, S.M. Genistein at a concentration present in soy infant formula inhibits Caco-2BBe cell proliferation by causing G2/M cell cycle arrest. J Nutr 2004, 134, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.F.; Wang, J.S.; Lu, J.F.; Kao, T.H.; Chen, B.H. Antiproliferation effect and mechanism of prostate cancer cell lines as affected by isoflavones from soybean cake. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.J.; Yeh, T.M.; Lei, H.Y.; Chow, N.H. The potential of soybean foods as a chemoprevention approach for human urinary tract cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, K. Synergistic effects of thearubigin and genistein on human prostate tumor cell (PC-3) growth via cell cycle arrest. Cancer Lett. 2000, 151, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Tophkhane, C.; Yang, S.; Bales, W.; Archer, L.; Osunkoya, A.; Thor, A.D.; Yang, X. Bcl-2 overexpression sensitizes MCF-7 cells to genistein by multiple mechanisms. Int. J. Oncol. 2007, 31, 867–874. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.R.; Mukherjee, P.; Gugger, E.T.; Tanaka, T.; Blackburn, G.L.; Clinton, S.K. Inhibition of murine bladder tumorigenesis by soy isoflavones via alterations in the cell cycle, apoptosis, and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 5231–5238. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, S.; Kikuno, N.; Nelles, J.; Noonan, E.; Tanaka, Y.; Kawamoto, K.; Hirata, H.; Li, L.C.; Zhao, H.; Okino, S.T.; Place, R.F.; Pookot, D.; Dahiya, R. Genistein induces the p21WAF1/CIP1 and p16INK4a tumor suppressor genes in prostate cancer cells by epigenetic mechanisms involving active chromatin modification. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 2736–2744. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.L.; Kung, M.L.; Chow, N.H.; Su, S.J. Genistein arrests hepatoma cells at G2/M phase: involvement of ATM activation and upregulation of p21waf1/cip1 and Wee1. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 67, 717–726. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, Y.; Amran, D.; de Blas, E.; Aller, P. Regulation of genistein-induced differentiation in human acute myeloid leukaemia cells (HL60, NB4) Protein kinase modulation and reactive oxygen species generation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009, 77, 384–396. [Google Scholar]

- Raffoul, J.J.; Wang, Y.; Kucuk, O.; Forman, J.D.; Sarkar, F.H.; Hillman, G.G. Genistein inhibits radiation-induced activation of NF-kappaB in prostate cancer cells promoting apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle arrest. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.C.; Klein, R.D.; Wei, Q.; Guan, Y.; Contois, J.H.; Wang, T.T.; Chang, S.; Hursting, S.D. Low-dose genistein induces cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and G(1) cell-cycle arrest in human prostate cancer cells. Mol. Carcinog. 2000, 29, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, R.S.; Li, J.; Singletary, K.W. Effects of genistein on cell proliferation and cell cycle arrest in nonneoplastic human mammary epithelial cells: involvement of Cdc2, p21(waf/cip1), p27(kip1), and Cdc25C expression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 61, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oki, T.; Sowa, Y.; Hirose, T.; Takagaki, N.; Horinaka, M.; Nakanishi, R.; Yasuda, C.; Yoshida, T.; Kanazawa, M.; Satomi, Y.; Nishino, H.; Miki, T.; Sakai, T. Genistein induces Gadd45 gene and G2/M cell cycle arrest in the DU145 human prostate cancer cell line. FEBS Lett. 2004, 577, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, A.; McCarthy, B.; Schwander, S.K.; Chang, V.; Kotenko, S.; Donepudi, S.; Lee, J.; Raveche, E. Genistein induces G2 arrest in malignant B cells by decreasing IL-10 secretion. Cell Cycle 2004, 3, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelletti, V.; Fioravanti, L.; Miodini, P.; Di Fronzo, G. Genistein blocks breast cancer cells in the G(2)M phase of the cell cycle. J. Cell Biochem. 2000, 79, 594–600. [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande, F.; Darbon, J.M. p21CIP1 is dispensable for the G2 arrest caused by genistein in human melanoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2000, 258, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande, F.; Darbon, J.M. Effects of structurally related flavonoids on cell cycle progression of human melanoma cells: regulation of cyclin-dependent kinases CDK2 and CDK1. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 61, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Darbon, J.M.; Penary, M.; Escalas, N.; Casagrande, F.; Goubin-Gramatica, F.; Baudouin, C.; Ducommun, B. Distinct Chk2 activation pathways are triggered by genistein and DNA-damaging agents in human melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 15363–15369. [Google Scholar]

- Rauth, S.; Kichina, J.; Green, A. Inhibition of growth and induction of differentiation of metastatic melanoma cells in vitro by genistein: chemosensitivity is regulated by cellular p53. Br. J. Cancer 1997, 75, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa, Y.; Marui, N.; Sakai, T.; Satomi, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Nishino, H.; Aoike, A. Genistein arrests cell cycle progression at G2-M. Cancer Res. 1993, 53, 1328–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, L.P.; Yu, X.Y.; Zhang, R.Q. Effects of genistein and daidzein on the cell growth, cell cycle, and differentiation of human and murine melanoma cells(1). J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.M.; Xiao, B.X.; Liu, D.H.; Grant, M.; Zhang, S.; Lai, Y.F.; Guo, Y.B.; Liu, Q. Biphasic effect of daidzein on cell growth of human colon cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004, 42, 1641–1646. [Google Scholar]

- Tijet, N.; Boutros, P.C.; Moffat, I.D.; Okey, A.B.; Tuomisto, J.; Pohjanvirta, R. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates distinct dioxin-dependent and dioxin-independent gene batteries. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, C.Y.; Park, M.; Kim, B.H.; Park, J.Y.; Park, M.S.; Jeong, Y.K.; Kwon, H.; Jung, H.K.; Kang, H.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, B.J. Gene expression profile by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in the liver of wild-type (AhR+/+) and aryl hydrocarbon receptor-deficient (AhR-/-) mice. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2006, 68, 663–668. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, K.W.; Köhle, C. Ah receptor: Dioxin-mediated toxic responses as hints to deregulated physiologic functions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miniero, R.; De Felip, E.; Ferri, F.; di Domenico, A. An overview of TCDD half-life in mammals and its correlation to body weight. Chemosphere 2001, 43, 839–844. [Google Scholar]

- Kerger, B.D.; Leung, H.W.; Scott, P.; Paustenbach, D.J.; Needham, L.L.; Patterson, D.G., Jr.; Gerthoux, P.M.; Mocarelli, P. Age- and concentration-dependent elimination half-life of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in Seveso children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1596–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, K.A.; Lockhart, C.A.; Huang, G.; Elferink, C.J. Sustained aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity attenuates liver regeneration. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, N.V.; Andersson, P.; Gradin, K.; Stein, P.; Dieckmann, A.; Pettersson, S.; Hanberg, A.; Poellinger, L. The dioxin/aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediates downregulation of osteopontin gene expression in a mouse model of gastric tumourigenesis. Oncogene 2005, 24, 3216–3222. [Google Scholar]

- Moennikes, O.; Loeppen, S.; Buchmann, A.; Andersson, P.; Ittrich, C.; Poellinger, L.; Schwarz, M. A constitutively active dioxin/aryl hydrocarbon receptor promotes hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 4707–4710. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, P.; McGuire, J.; Rubio, C.; Gradin, K.; Whitelaw, M.L.; Pettersson, S.; Hanberg, A.; Poellinger, L. A constitutively active dioxin/aryl hydrocarbon receptor induces stomach tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 9990–9995. [Google Scholar]