Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Outcomes in Older Australian Adults—Results from the Randomized Controlled D-Health Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

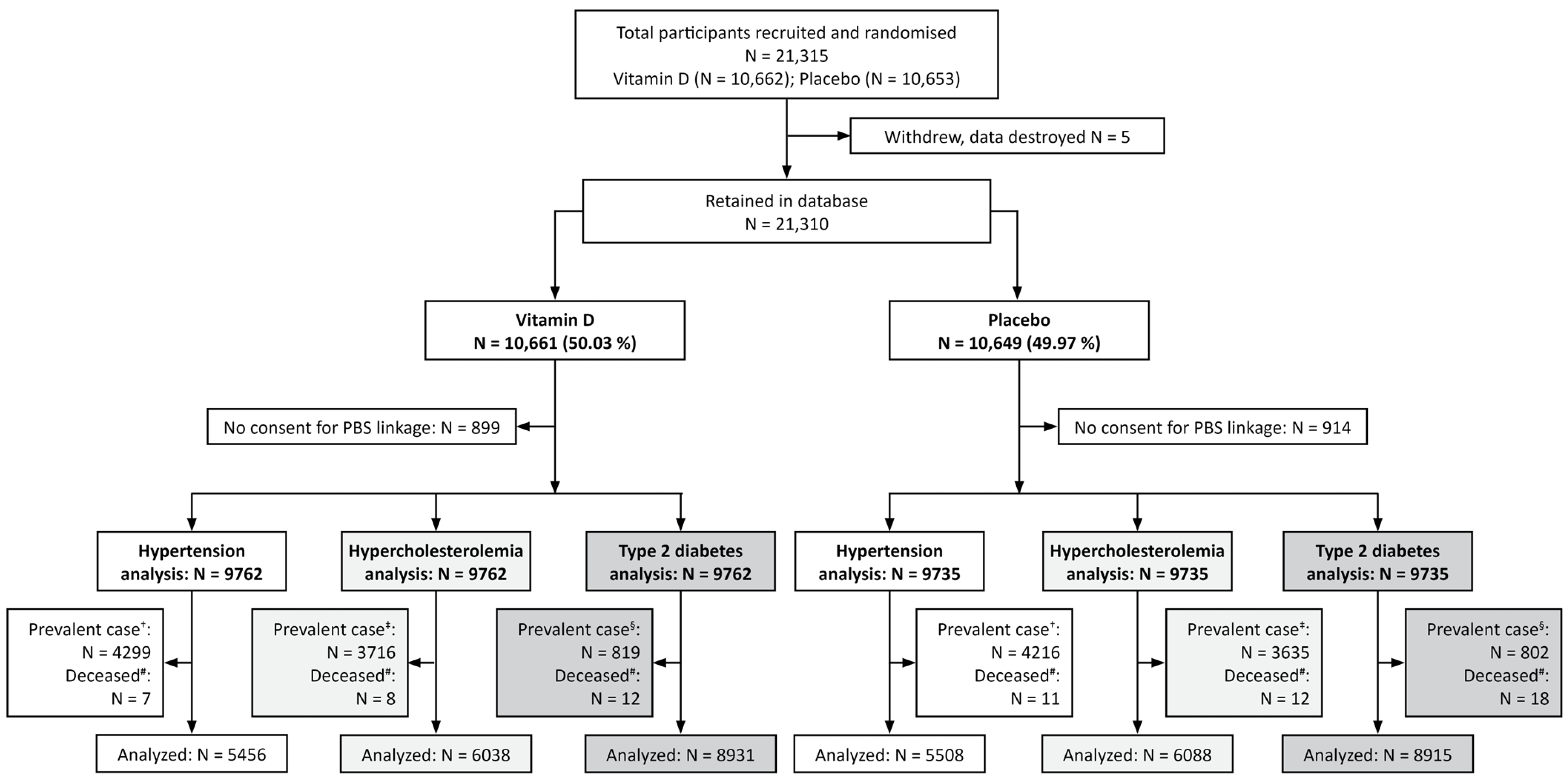

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design, Participants, and Intervention

2.2. Baseline Characteristics

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Follow-Up and Eligibility

2.5. Monitoring Adherence and Adverse Events

2.6. Blinding

2.7. Statistical Methods

2.8. Subgroup Analyses

2.9. Sensitivity Analysis

2.10. Ethics Approval and Trial Registration

2.11. Role of the Funding Source

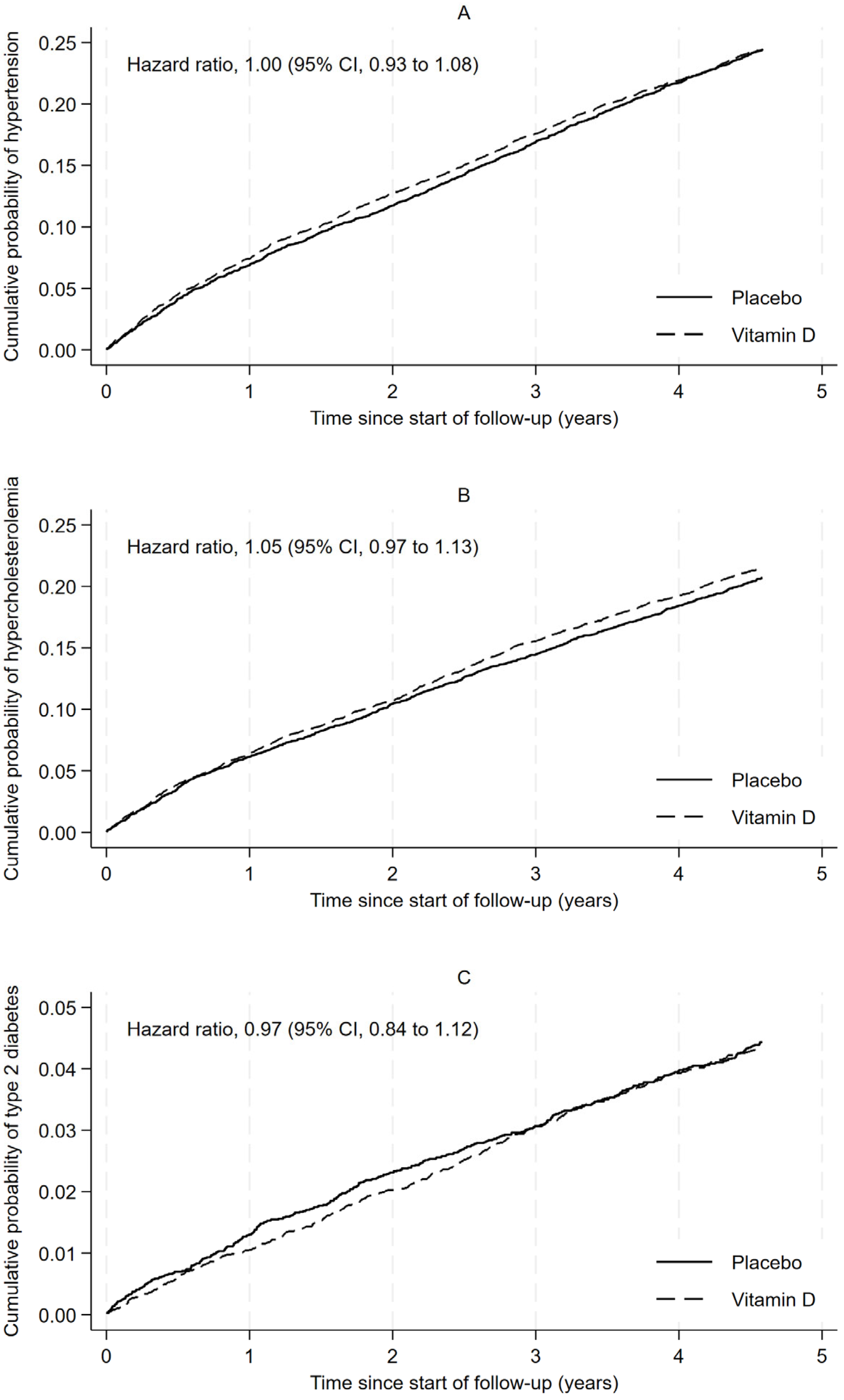

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 25(OH)D | 25-hydroxyvitamin D |

| ATC | anatomic therapeutic classification |

| BMI | body mass index |

| FPSM | flexible parametric survival model |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| IU | International unit |

| PBS | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| T2D | type 2 diabetes |

References

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Amann, M.; Anderson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; Aryee, M.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2224–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. Urgent Action Needed as Global Diabetes Cases Increase Four-Fold over Past Decades. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-11-2024-urgent-action-needed-as-global-diabetes-cases-increase-four-fold-over-past-decades (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Argano, C.; Mirarchi, L.; Amodeo, S.; Orlando, V.; Torres, A.; Corrao, S. The Role of Vitamin D and Its Molecular Bases in Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and Cardiovascular Disease: State of the Art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, S.; Tomaschitz, A.; Ritz, E.; Pieber, T.R. Vitamin D status and arterial hypertension: A systematic review. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2009, 6, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, L.; Watanabe, M.; Ryoden, Y.; Usuda, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Khambu, B.; Takashima, M.; Sato, S.I.; Sakai, J.; Nagasawa, K.; et al. Vitamin D Metabolite, 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, Regulates Lipid Metabolism by Inducing Degradation of SREBP/SCAP. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Atkins, A.; Downes, M.; Wei, Z. Vitamin D in Diabetes: Uncovering the Sunshine Hormone’s Role in Glucose Metabolism and Beyond. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Apekey, T.A.; Steur, M. Vitamin D and risk of future hypertension: Meta-analysis of 283,537 participants. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 28, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadorpour, S.; Hajhashemy, Z.; Saneei, P. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and dyslipidemia: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 81, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, L.; Pittas, A.G.; Del Gobbo, L.C.; Zhang, C.; Manson, J.E.; Hu, F.B. Blood 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels and incident type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1422–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimaleswaran, K.S.; Cavadino, A.; Berry, D.J.; Jorde, R.; Dieffenbach, A.K.; Lu, C.; Alves, A.C.; Heerspink, H.J.; Tikkanen, E.; Eriksson, J.; et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: A mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, X.M.; Videm, V.; Sheehan, N.A.; Chen, Y.; Langhammer, A.; Sun, Y.Q. Potential causal associations of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D with lipids: A Mendelian randomization approach of the HUNT study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Bennett, D.A.; Millwood, I.Y.; Parish, S.; McCarthy, M.I.; Mahajan, A.; Lin, X.; Bragg, F.; Guo, Y.; Holmes, M.V.; et al. Association of vitamin D with risk of type 2 diabetes: A Mendelian randomisation study in European and Chinese adults. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Yu, S.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, X. Effect of vitamin D on blood pressure and hypertension in the general population: An update meta-analysis of cohort studies and randomized controlled trials. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radkhah, N.; Zarezadeh, M.; Jamilian, P.; Ostadrahimi, A. The Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Lipid Profiles: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 1479–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, H.; Tang, J.; Li, J.; Chong, W.; Hai, Y.; Feng, Y.; Lunsford, L.D.; Xu, P.; Jia, D.; et al. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes in Patients with Prediabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittas, A.G.; Kawahara, T.; Jorde, R.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Vickery, E.M.; Angellotti, E.; Nelson, J.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Balk, E.M. Vitamin D and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes in People with Prediabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Individual Participant Data From 3 Randomized Clinical Trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, D.K.; Pradhan, A.D.; Duran, E.K.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Buring, J.E.; Cook, N.R.; Mora, S.; Manson, J.E. Vitamin D supplementation vs. placebo and incident type 2 diabetes in an ancillary study of the randomized Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Li, X. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Glucose and Insulin Homeostasis and Incident Diabetes among Nondiabetic Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 2018, 7908764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, R.E.; Baxter, C.; Duarte Romero, B.; McLeod, D.S.A.; English, D.R.; Armstrong, B.K.; Ebeling, P.R.; Hartel, G.; Kimlin, M.G.; O’Connell, R.; et al. The D-Health Trial: A randomised controlled trial of the effect of vitamin D on mortality. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Waterhouse, M.; English, D.R.; McLeod, D.S.; Armstrong, B.K.; Baxter, C.; Duarte Romero, B.; Ebeling, P.R.; Hartel, G.; Kimlin, M.G.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation and major cardiovascular events: D-Health randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2023, 381, e075230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, R.E.; Armstrong, B.K.; Baxter, C.; Duarte Romero, B.; Ebeling, P.; English, D.R.; Kimlin, M.G.; McLeod, D.S.; RL, O.C.; van der Pols, J.C.; et al. The D-Health Trial: A randomized trial of vitamin D for prevention of mortality and cancer. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2016, 48, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, M.; Baxter, C.; Duarte Romero, B.; McLeod, D.S.A.; English, D.R.; Armstrong, B.K.; Clarke, M.W.; Ebeling, P.R.; Hartel, G.; Kimlin, M.G.; et al. Predicting deseasonalised serum 25 hydroxy vitamin D concentrations in the D-Health Trial: An analysis using boosted regression trees. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 104, 106347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, M.; English, D.R.; Armstrong, B.K.; Baxter, C.; Duarte Romero, B.; Ebeling, P.R.; Hartel, G.; Kimlin, M.G.; McLeod, D.S.A.; O’Connell, R.L.; et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation for reduction of mortality and cancer: Statistical analysis plan for the D-Health Trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2019, 14, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saul, B. Smd: Compute Standardized Mean Differences. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=smd (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Hypertension and High Measured Blood Pressure. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/hypertension-and-measured-high-blood-pressure/latest-release (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. High Cholesterol. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/high-cholesterol/latest-release (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Diabetes. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/diabetes/2022#characteristics-of-people-with-diabetes (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: First Results 2014-15—Australia. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4364.0.55.0012014-15?OpenDocument (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Lujic, S.; Simpson, J.M.; Zwar, N.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Jorm, L. Multimorbidity in Australia: Comparing estimates derived using administrative data sources and survey data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkiss, S.; Keegel, T.; Vally, H.; Wollersheim, D. Estimates of drug treated diabetes incidence and prevalence using Australian administrative pharmaceutical data. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 2021, 6, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkiss, S.F.; Keegel, T.; Vally, H.; Wollersheim, D. A comparison of Australian chronic disease prevalence estimates using administrative pharmaceutical dispensing data with international and community survey data. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 2020, 5, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.; Bauman, A.; Ding, D. Association between lifestyle risk factors and incident hypertension among middle-aged and older Australians. Prev. Med. 2019, 118, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, K.L.; Ray, R.M.; Van Horn, L.; Manson, J.E.; Allison, M.A.; Black, H.R.; Beresford, S.A.; Connelly, S.A.; Curb, J.D.; Grimm, R.H., Jr.; et al. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on blood pressure: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial. Hypertension 2008, 52, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scragg, R.; Stewart, A.W.; Waayer, D.; Lawes, C.M.M.; Toop, L.; Sluyter, J.; Murphy, J.; Khaw, K.T.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Effect of Monthly High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiovascular Disease in the Vitamin D Assessment Study: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczyk, M.K.; Zheng, J.; Davey Smith, G.; Gaunt, T.R. Systematic comparison of Mendelian randomisation studies and randomised controlled trials using electronic databases. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Biomedical Results for Nutrients, 2011–2012. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/australian-health-survey-biomedical-results-nutrients/latest-release#data-download (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index 2025. Available online: https://atcddd.fhi.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

| Incident Hypertension ≈ | Incident Hypercholesterolemia ◎ | Incident Type 2 Diabetes ✻ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||||||

| Characteristic | Placebo (N = 5508) | Vitamin D (N = 5456) | SMD | Placebo (N = 6088) | Vitamin D (N = 6038) | SMD | Placebo (N = 8915) | Vitamin D (N = 8931) | SMD |

| Age (years) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| 60–64 | 1659 (30.1) | 1600 (29.3) | 1796 (29.5) | 1771 (29.3) | 2237 (25.1) | 2215 (24.8) | |||

| 65–69 | 1596 (29.0) | 1598 (29.3) | 1740 (28.6) | 1718 (28.5) | 2475 (27.8) | 2486 (27.8) | |||

| 70–74 | 1373 (24.9) | 1344 (24.6) | 1502 (24.7) | 1495 (24.8) | 2399 (26.9) | 2416 (27.1) | |||

| ≥75 | 880 (16.0) | 914 (16.8) | 1050 (17.2) | 1054 (17.5) | 1804 (20.2) | 1814 (20.3) | |||

| Sex | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Men | 2844 (51.6) | 2824 (51.8) | 3110 (51.1) | 3080 (51.0) | 4746 (53.2) | 4792 (53.7) | |||

| Women | 2664 (48.4) | 2632 (48.2) | 2978 (48.9) | 2958 (49.0) | 4169 (46.8) | 4139 (46.3) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||

| <25 | 1998 (36.3) | 2051 (37.6) | 2063 (33.9) | 2105 (34.9) | 2756 (30.9) | 2877 (32.2) | |||

| 25 to <30 | 2362 (42.9) | 2295 (42.1) | 2613 (42.9) | 2490 (41.2) | 3897 (43.7) | 3795 (42.5) | |||

| ≥30 | 1118 (20.3) | 1089 (20.0) | 1384 (22.7) | 1418 (23.5) | 2218 (24.9) | 2225 (24.9) | |||

| Missing | 30 (0.5) | 21 (0.4) | 28 (0.5) | 25 (0.4) | 44 (0.5) | 34 (0.4) | |||

| Predicted 25(OH)D concentration (nmol/L) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||

| <50 | 1291 (23.4) | 1215 (22.3) | 1446 (23.8) | 1394 (23.1) | 2122 (23.8) | 2039 (22.8) | |||

| ≥50 | 4217 (76.6) | 4241 (77.7) | 4642 (76.2) | 4644 (76.9) | 6793 (76.2) | 6892 (77.2) | |||

| Highest qualification obtained | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | ||||||

| None | 438 (8.0) | 479 (8.8) | 506 (8.3) | 520 (8.6) | 826 (9.3) | 855 (9.6) | |||

| School or intermediate certificate | 857 (15.6) | 868 (15.9) | 973 (16.0) | 985 (16.3) | 1445 (16.2) | 1492 (16.7) | |||

| Higher school or leaving certificate | 802 (14.6) | 716 (13.1) | 862 (14.2) | 804 (13.3) | 1279 (14.3) | 1184 (13.3) | |||

| Apprenticeship or certificate | 1825 (33.1) | 1759 (32.2) | 2029 (33.3) | 1935 (32.0) | 2985 (33.5) | 2896 (32.4) | |||

| University degree or higher | 1537 (27.9) | 1575 (28.9) | 1662 (27.3) | 1736 (28.8) | 2282 (25.6) | 2416 (27.1) | |||

| Missing | 49 (0.9) | 59 (1.1) | 56 (0.9) | 58 (1.0) | 98 (1.1) | 88 (1.0) | |||

| Self-rated overall health | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Excellent or very good | 3440 (62.5) | 3420 (62.7) | 3686 (60.5) | 3674 (60.8) | 5084 (57.0) | 5108 (57.2) | |||

| Good | 1642 (29.8) | 1647 (30.2) | 1936 (31.8) | 1866 (30.9) | 3054 (34.3) | 3045 (34.1) | |||

| Fair or poor | 343 (6.2) | 300 (5.5) | 382 (6.3) | 401 (6.6) | 649 (7.3) | 631 (7.1) | |||

| Missing | 83 (1.5) | 89 (1.6) | 84 (1.4) | 97 (1.6) | 128 (1.4) | 147 (1.6) | |||

| Self-rated quality of life | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Excellent or very good | 3898 (70.8) | 3832 (70.2) | 4220 (69.3) | 4151 (68.7) | 6074 (68.1) | 6027 (67.5) | |||

| Good | 1241 (22.5) | 1265 (23.2) | 1455 (23.9) | 1485 (24.6) | 2217 (24.9) | 2262 (25.3) | |||

| Fair or poor | 257 (4.7) | 245 (4.5) | 292 (4.8) | 278 (4.6) | 443 (5.0) | 453 (5.1) | |||

| Missing | 112 (2.0) | 114 (2.1) | 121 (2.0) | 124 (2.1) | 181 (2.0) | 189 (2.1) | |||

| Prevalent hypertension † | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||||||

| No | 5508 (100) | 5456 (100) | 4267 (70.1) | 4155 (68.8) | 5336 (59.9) | 5266 (59.0) | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1821 (29.9) | 1883 (31.2) | 3579 (40.1) | 3665 (41.0) | |||

| Prevalent hypercholesterolemia ‡ | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||

| No | 4267 (77.5) | 4155 (76.2) | 6088 (100) | 6038 (100) | 5925 (66.5) | 5857 (65.6) | |||

| Yes | 1241 (22.5) | 1301 (23.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2990 (33.5) | 3074 (34.4) | |||

| Prevalent diabetes § | 0.02 | 0.02 | <0.01 | ||||||

| No | 5336 (96.9) | 5266 (96.5) | 5925 (97.3) | 5857 (97.0) | 8915 (100) | 8931 (100) | |||

| Yes | 172 (3.1) | 190 (3.5) | 163 (2.7) | 181 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Smoking history | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Never | 3106 (56.4) | 3092 (56.7) | 3433 (56.4) | 3431 (56.8) | 4915 (55.1) | 4918 (55.1) | |||

| Ex-smoker | 2092 (38.0) | 2109 (38.7) | 2324 (38.2) | 2337 (38.7) | 3538 (39.7) | 3610 (40.4) | |||

| Current | 266 (4.8) | 217 (4.0) | 280 (4.6) | 231 (3.8) | 388 (4.4) | 344 (3.9) | |||

| Missing | 44 (0.8) | 38 (0.7) | 51 (0.8) | 39 (0.6) | 74 (0.8) | 59 (0.7) | |||

| Alcohol consumption (drinks/week) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||

| <1 | 1250 (22.7) | 1226 (22.5) | 1379 (22.7) | 1390 (23.0) | 2020 (22.7) | 1993 (22.3) | |||

| 1 to 7 | 2471 (44.9) | 2468 (45.2) | 2709 (44.5) | 2669 (44.2) | 3887 (43.6) | 3839 (43.0) | |||

| >7 to 14 | 964 (17.5) | 1002 (18.4) | 1066 (17.5) | 1109 (18.4) | 1579 (17.7) | 1677 (18.8) | |||

| >14 | 615 (11.2) | 574 (10.5) | 703 (11.5) | 658 (10.9) | 1106 (12.4) | 1108 (12.4) | |||

| Missing | 208 (3.8) | 186 (3.4) | 231 (3.8) | 212 (3.5) | 323 (3.6) | 314 (3.5) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Duarte Romero, B.L.; Armstrong, B.K.; Baxter, C.; English, D.R.; Ebeling, P.R.; Hartel, G.; Kimlin, M.G.; Na, R.; McLeod, D.S.A.; Pham, H.; et al. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Outcomes in Older Australian Adults—Results from the Randomized Controlled D-Health Trial. Nutrients 2026, 18, 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020357

Duarte Romero BL, Armstrong BK, Baxter C, English DR, Ebeling PR, Hartel G, Kimlin MG, Na R, McLeod DSA, Pham H, et al. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Outcomes in Older Australian Adults—Results from the Randomized Controlled D-Health Trial. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):357. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020357

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuarte Romero, Briony L., Bruce K. Armstrong, Catherine Baxter, Dallas R. English, Peter R. Ebeling, Gunter Hartel, Michael G. Kimlin, Renhua Na, Donald S. A. McLeod, Hai Pham, and et al. 2026. "Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Outcomes in Older Australian Adults—Results from the Randomized Controlled D-Health Trial" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020357

APA StyleDuarte Romero, B. L., Armstrong, B. K., Baxter, C., English, D. R., Ebeling, P. R., Hartel, G., Kimlin, M. G., Na, R., McLeod, D. S. A., Pham, H., Ross, T., van der Pols, J. C., Venn, A. J., Webb, P. M., Whiteman, D. C., Neale, R. E., & Waterhouse, M. (2026). Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Outcomes in Older Australian Adults—Results from the Randomized Controlled D-Health Trial. Nutrients, 18(2), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020357