A Methodological Framework for Aggregating Branded Food Composition Data in mHealth Nutrition Databases: A Case Presentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

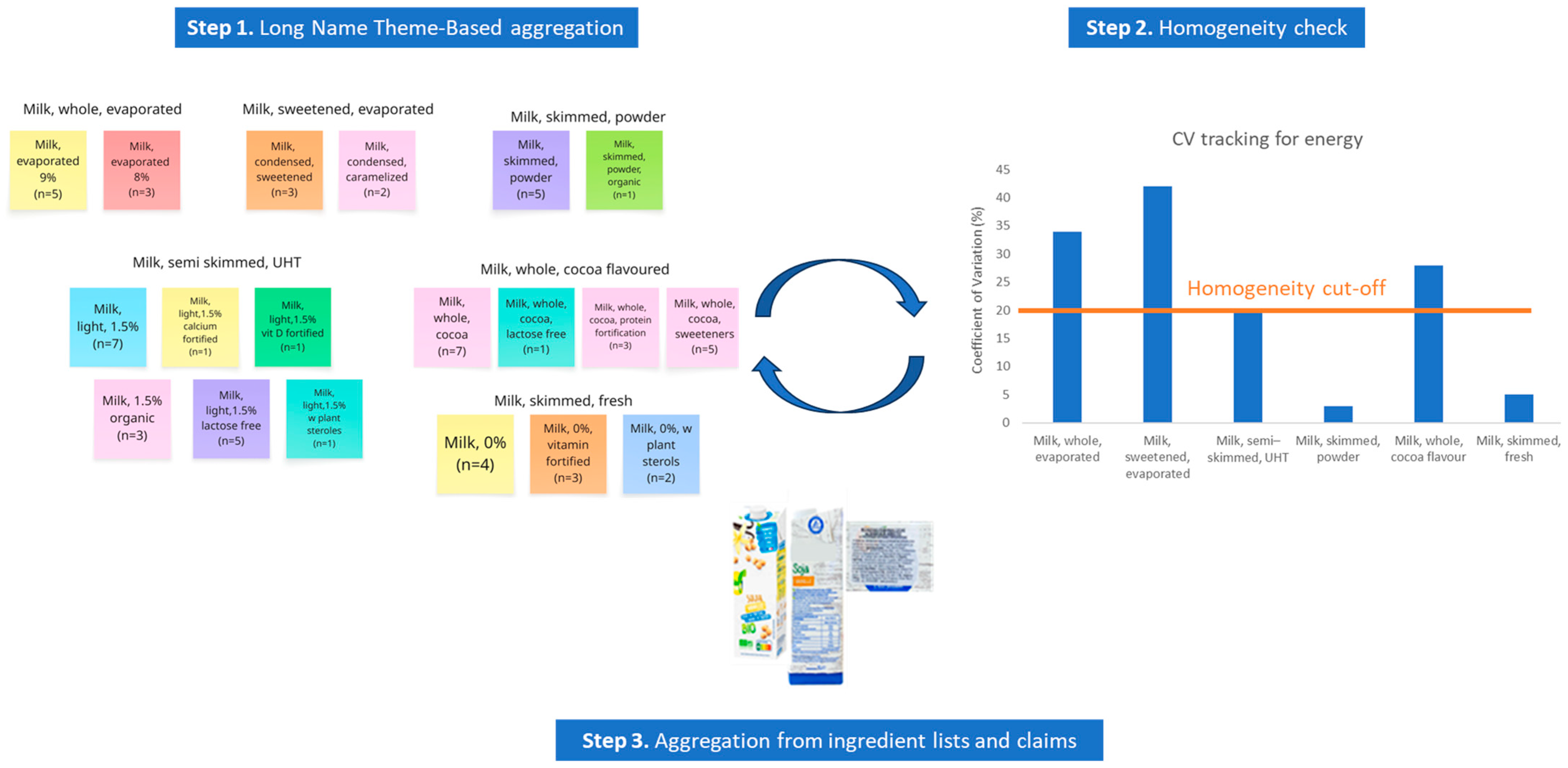

2.2. Methodology of Aggregated Value Derivation

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

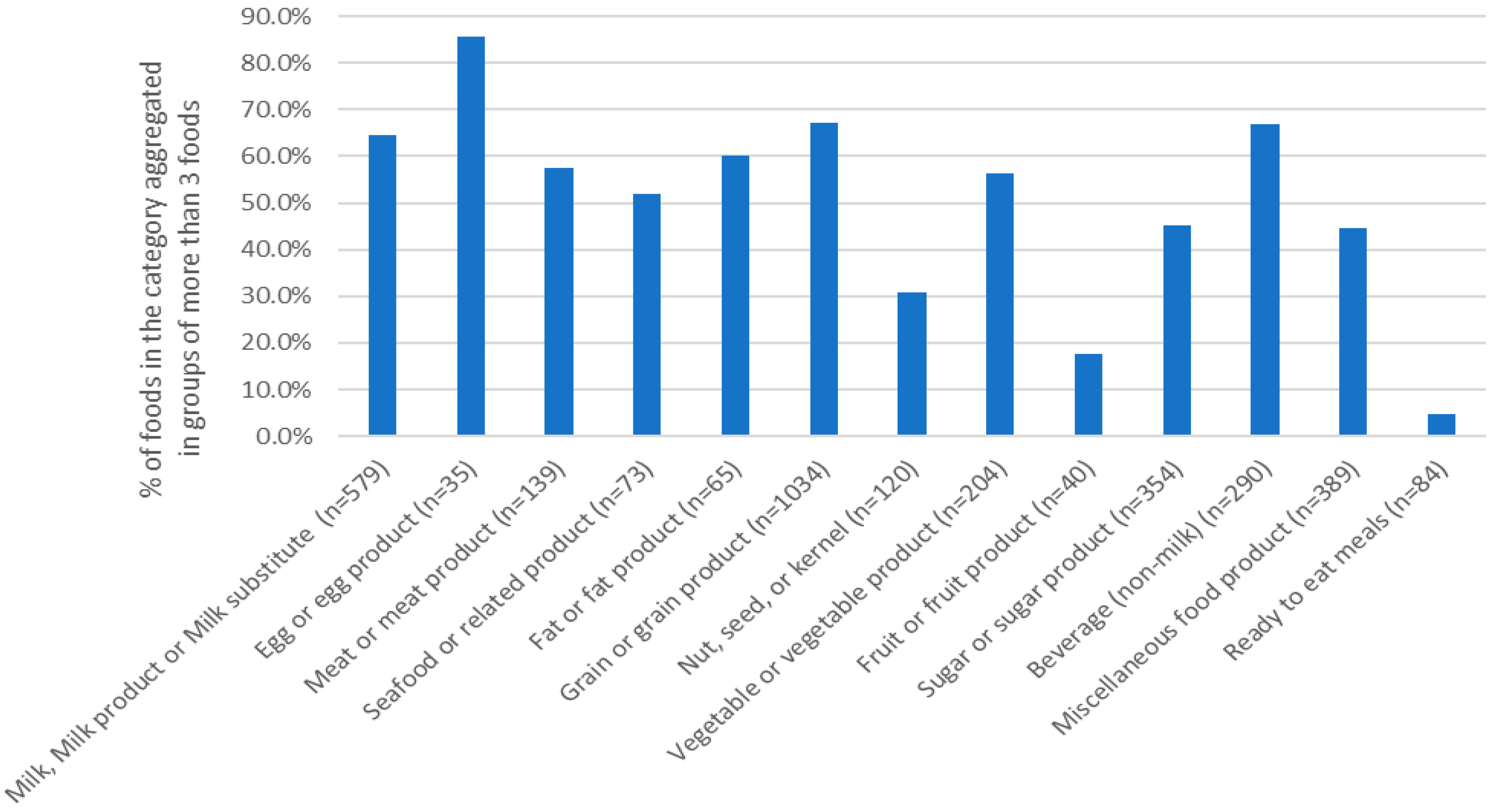

3.1. Data Aggregation to Derive Generic Food Names from Branded Data

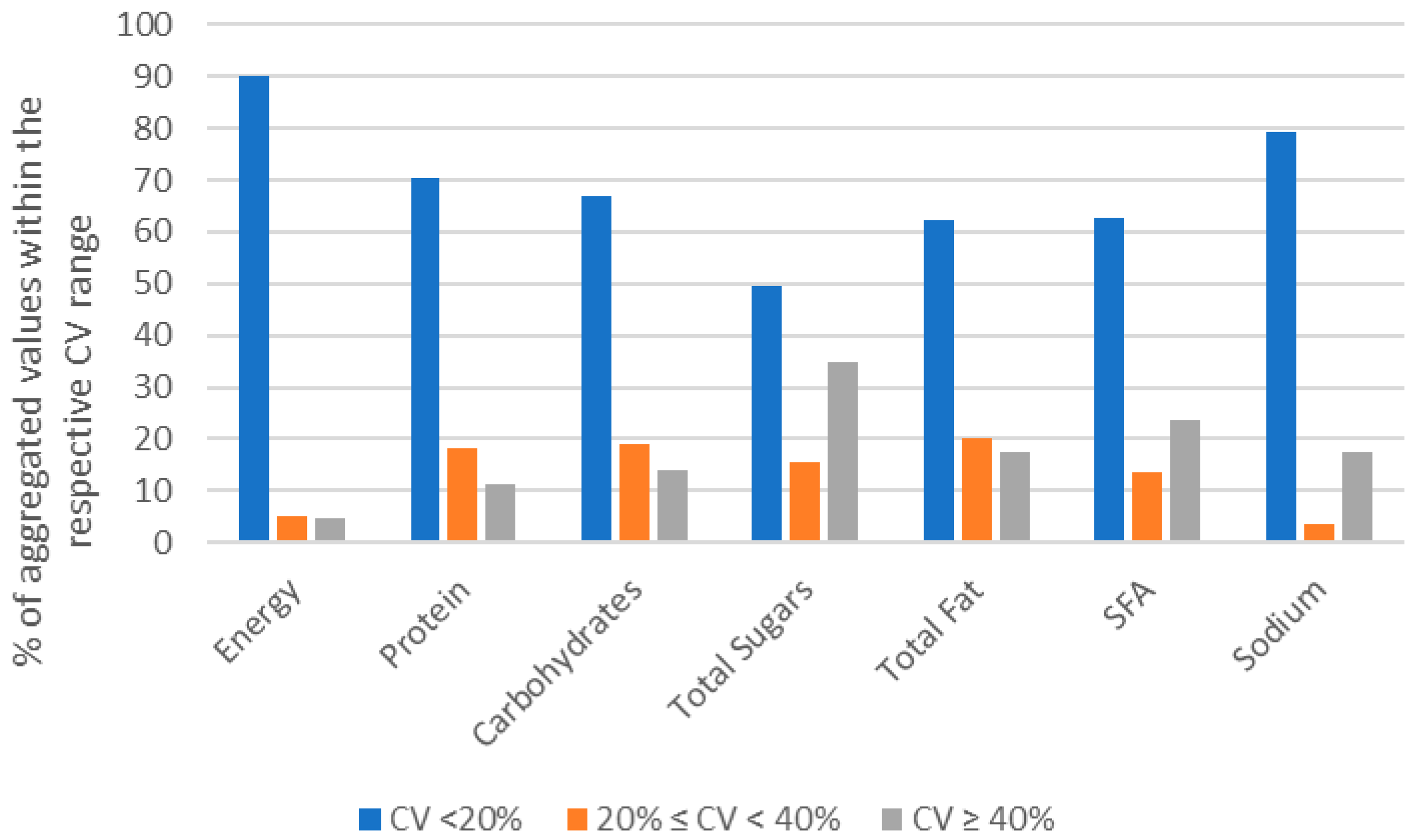

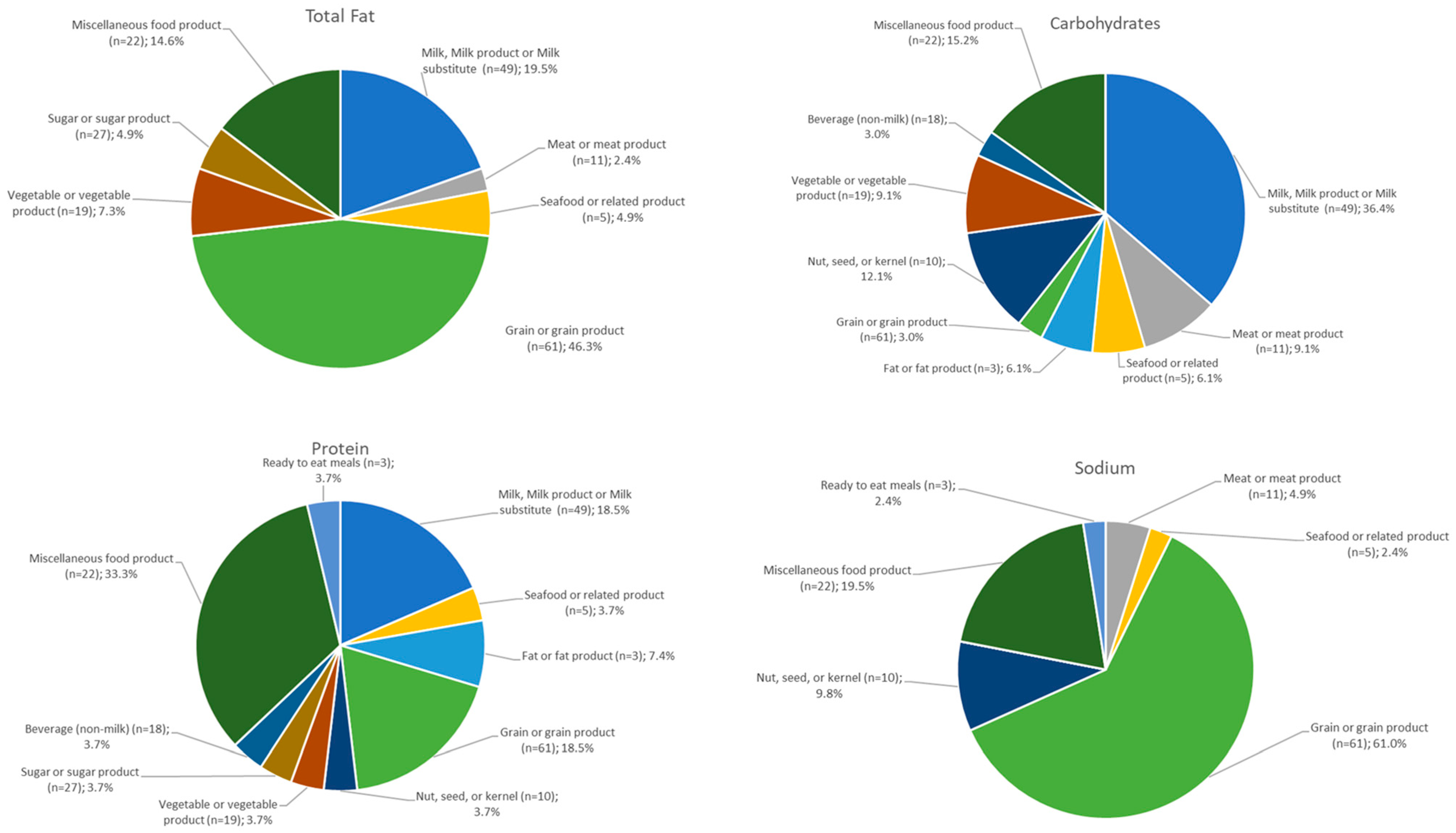

3.2. Compositional Homogeneity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BFCD | Branded Food Composition Database |

| FCD | Food Composition Database |

| EuroFIR | European Food Information Resource |

| SFA | Saturated Fatty Acid |

| TF | Total Fat |

| TS | Total Sugar |

| CHO | Carbohydrate |

References

- Ferrara, G.; Kim, J.; Lin, S.; Hua, J.; Seto, E. A Focused Review of Smartphone Diet-Tracking Apps: Usability, Functionality, Coherence With Behavior Change Theory, and Comparative Validity of Nutrient Intake and Energy Estimates. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, Y. mHealthApps: A Repository and Database of Mobile Health Apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015, 3, e4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujia, C.; Ferro, Y.; Mazza, E.; Maurotti, S.; Montalcini, T.; Pujia, A. The Role of Mobile Apps in Obesity Management: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e66887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.C.W.; Takemura, N.; Lam, W.W.T.; Ho, M.M.; Lee, A.M.; Chan, W.Y.Y.; Fong, D.Y.T. Efficacy of Mobile App–Based Dietary Interventions Among Cancer Survivors: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2025, 13, e65505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarroll, R.; Eyles, H.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Effectiveness of Mobile Health (mHealth) Interventions for Promoting Healthy Eating in Adults: A Systematic Review. Prev. Med. 2017, 105, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiuchi, K.; Brytek-Matera, A. Mobile Health (mHealth) Technology for Eating-Related Behaviour and Health Problems Related to Obesity in Japan: A Systematic Review. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2025, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, C.; Harnack, L.; Pereira, M.A. Assessment of the Accuracy of Nutrient Calculations of Five Popular Nutrition Tracking Applications. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Ahmed, M.; Staiano, A.E.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; Gough, C.; Petersen, J.M.; Yin, Z.; Vandelanotte, C.; Kracht, C.; Fiedler, J.; et al. Lifestyle eHealth and mHealth Interventions for Children and Adolescents: Systematic Umbrella Review and Meta–Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e69065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, H.; Singh, B.; Staiano, A.E.; Gough, C.; Ahmed, M.; Fiedler, J.; Timm, I.; Wunsch, K.; Button, A.; Yin, Z.; et al. Effectiveness of mHealth Interventions Targeting Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, Sleep or Nutrition on Emotional, Behavioural and Eating Disorders in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1593677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Ahmed, M.; Staiano, A.E.; Gough, C.; Petersen, J.; Vandelanotte, C.; Kracht, C.; Huong, C.; Yin, Z.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; et al. A Systematic Umbrella Review and Meta-Meta-Analysis of eHealth and mHealth Interventions for Improving Lifestyle Behaviours. Npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, A.M.; O’Connor, S.; Giannelli, V.; Yap, M.L.; Tang, L.M.; Roy, R.; Louie, J.C.Y.; Hebden, L.; Kay, J.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Electronic Dietary Intake Assessment (e-DIA): Comparison of a Mobile Phone Digital Entry App for Dietary Data Collection With 24-Hour Dietary Recalls. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015, 3, e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.A.; Adhikari, V.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Nutrient Composition Databases in the Age of Big Data: FoodDB, a Comprehensive, Real-Time Database Infrastructure. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkley, S.; Gallo-Franco, J.J.; Vázquez-Manjarrez, N.; Chaura, J.; Quartey, N.K.A.; Toulabi, S.B.; Odenkirk, M.T.; Jermendi, E.; Laporte, M.-A.; Lutterodt, H.E.; et al. The State of Food Composition Databases: Data Attributes and FAIR Data Harmonization in the Era of Digital Innovation. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1552367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaghan, J.; Backholer, K.; McKelvey, A.-L.; Christidis, R.; Borda, A.; Calyx, C.; Crocetti, A.; Driessen, C.; Zorbas, C. Citizen Science Approaches to Crowdsourcing Food Environment Data: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocké, M.C.; Westenbrink, S.; van Rossum, C.T.M.; Temme, E.H.M.; van der Vossen-Wijmenga, W.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J. The Essential Role of Food Composition Databases for Public Health Nutrition—Experiences from the Netherlands. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 101, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsokefalou, M.; Roe, M.; Turrini, A.; Costa, H.S.; Martinez-Victoria, E.; Marletta, L.; Berry, R.; Finglas, P.; Kapsokefalou, M.; Roe, M.; et al. Food Composition at Present: New Challenges. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maringer, M.; van’t Veer, P.; Klepacz, N.; Verain, M.C.D.; Normann, A.; Ekman, S.; Timotijevic, L.; Raats, M.M.; Geelen, A. User-Documented Food Consumption Data from Publicly Available Apps: An Analysis of Opportunities and Challenges for Nutrition Research. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazen, W.; Jeanne, J.-F.; Demaretz, L.; Schäfer, F.; Fagherazzi, G. Rethinking the Use of Mobile Apps for Dietary Assessment in Medical Research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Bertrand, S.; Galy, O.; Raubenheimer, D.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Caillaud, C. The Design and Development of a Food Composition Database for an Electronic Tool to Assess Food Intake in New Caledonian Families. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Whitehead, M.; Sheats, J.Q.; Mastromonico, J.; Hardy, D.; Smith, S.A. Smartphone Applications for Promoting Healthy Diet and Nutrition: A Literature Review. Jacobs J. Food Nutr. 2015, 2, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Branded Food Database|Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science-data/food-nutrient-databases/branded-food-database (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Pravst, I.; Hribar, M.; Žmitek, K.; Blažica, B.; Koroušić Seljak, B.; Kušar, A. Branded Foods Databases as a Tool to Support Nutrition Research and Monitoring of the Food Supply: Insights From the Slovenian Composition and Labeling Information System. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 798576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westenbrink, S.; van der Vossen-Wijmenga, W.; Toxopeus, I.; Milder, I.; Ocké, M. LEDA, the Branded Food Database in the Netherlands: Data Challenges and Opportunities. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 102, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrick, B.; Kretser, A.; McKillop, K. Update on “A Partnership for Public Health: USDA Global Branded Food Products Database”. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 105, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Lozano, M.; Cantarero-Villanueva, I.; Martin-Martin, L.; Galiano-Castillo, N.; Sanchez, M.-J.; Fernández-Lao, C.; Postigo-Martin, P.; Arroyo-Morales, M. A Mobile System to Improve Quality of Life Via Energy Balance in Breast Cancer Survivors (BENECA mHealth): Prospective Test-Retest Quasiexperimental Feasibility Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e14136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziesemer, K.; König, L.M.; Boushey, C.J.; Villinger, K.; Wahl, D.R.; Butscher, S.; Müller, J.; Reiterer, H.; Schupp, H.T.; Renner, B. Occurrence of and Reasons for “Missing Events” in Mobile Dietary Assessments: Results From Three Event-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment Studies. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e15430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darby, A.; Strum, M.W.; Holmes, E.; Gatwood, J. A Review of Nutritional Tracking Mobile Applications for Diabetes Patient Use. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2016, 18, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.C.; Burley, V.J.; Nykjaer, C.; Cade, J.E. ‘My Meal Mate’ (MMM): Validation of the Diet Measures Captured on a Smartphone Application to Facilitate Weight Loss. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocké, M.; Dinnissen, C.S.; van den Bogaard, C.; Beukers, M.; Drijvers, J.; Sanderman-Nawijn, E.; van Rossum, C.; Toxopeus, I. A Smartphone Food Record App Developed for the Dutch National Food Consumption Survey: Relative Validity Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e50196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Schermel, A.; Lee, J.; Weippert, M.; Franco-Arellano, B.; L’Abbé, M. Development of the Food Label Information Program: A Comprehensive Canadian Branded Food Composition Database. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 825050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poti, J.M.; Yoon, E.; Hollingsworth, B.; Ostrowski, J.; Wandell, J.; Miles, D.R.; Popkin, B.M. Development of a Food Composition Database to Monitor Changes in Packaged Foods and Beverages. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 64, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krušič, S.; Hristov, H.; Hribar, M.; Lavriša, Ž.; Žmitek, K.; Pravst, I. Changes in the Sodium Content in Branded Foods in the Slovenian Food Supply (2011–2020). Nutrients 2023, 15, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, J.; Pomerleau, S.; Gagnon, P.; Gilbert-Moreau, J.; Lemieux, S.; Plante, C.; Paquette, M.-C.; Labonté, M.-È.; Provencher, V. Assessing Nutritional Value of Ready-to-Eat Breakfast Cereals in the Province of Quebec (Canada): A Study from the Food Quality Observatory. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2397–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlassopoulos, A.; Katidi, A.; Kapsokefalou, M. Performance and Discriminatory Capacity of Nutri-Score in Branded Foods in Greece. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 993238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naravane, T.; Tagkopoulos, I. Machine Learning Models to Predict Micronutrient Profile in Food after Processing. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, B.K.; Chandan, N.S.; Marangappanavar, D.N.; Indira, S.; Kumar, G. Classifying Food Ingredients Using Machine Learning on Nutritional and Biochemical Data. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, R.; Coluccia, S.; Marinoni, M.; Falcon, A.; Fiori, F.; Serra, G.; Ferraroni, M.; Edefonti, V.; Parpinel, M.; Bianco, R.; et al. 2D Prediction of the Nutritional Composition of Dishes from Food Images: Deep Learning Algorithm Selection and Data Curation Beyond the Nutrition5k Project. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakopoulos, F.S.; Sfakianos, M.; Georga, E.I.; Mavrokotas, K.I.; Katsarou, D.N.; Chalatsis, K.; Zapadiotis, C.; Panousi, A.; Plimakis, S.; Eleftheriou, S.; et al. MedDietAgent: An AI-Based Mobile App for Harmonizing Individuals’ Dietary Choices with the Mediterranean Diet Pattern. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 July 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- INFOODS: Food Composition Databases for Greece. Available online: https://www.fao.org/infoods/infoods/tables-and-databases/europe/en/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Katidi, A.; Vlassopoulos, A.; Kapsokefalou, M. Development of the Hellenic Food Thesaurus (HelTH), a Branded Food Composition Database: Aims, Design and Preliminary Findings. Food Chem. 2021, 347, 129010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katidi, A.; Xypolitaki, K.; Vlassopoulos, A.; Kapsokefalou, M. Nutritional Quality of Plant-Based Meat and Dairy Imitation Products and Comparison with Animal-Based Counterparts. Nutrients 2023, 15, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.F.; Lynn, F.; Meade, B.D. Use of Coefficient of Variation in Assessing Variability of Quantitative Assays. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2002, 9, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarry, A.; Rice, J.; O’Connor, E.M.; Tierney, A.C.; Scarry, A.; Rice, J.; O’Connor, E.M.; Tierney, A.C. Usage of Mobile Applications or Mobile Health Technology to Improve Diet Quality in Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, S.; Vlassopoulos, A.; Kapsokefalou, M. Foods “Sources of” or “High in” Vitamins and Minerals: Fortified or Natural? Use of the Greek Branded Food Composition Database (HelTH). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 144, 107721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, K.M.; He, F.J.; Alderton, S.A.; MacGregor, G.A. Cross-Sectional Survey of the Amount of Sugar and Energy in Cakes and Biscuits on Sale in the UK for the Evaluation of the Sugar-Reduction Programme. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada, H. Nutrient Value of Some Common Foods. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/nutrient-data/table-3-baked-goods-nutrient-value-some-common-foods-2008.html (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Ziraldo, E.R.; Hu, G.; Khan, A.; L’Abbé, M.R. Investigating Reformulation in the Canadian Food Supply between 2017 and 2020 and Its Impact on Food Prices. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghian, H.; Hallström, E.; Bianchi, M.; Bryngelsson, S. Nutritional Profile of Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives in the Swedish Market. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 8, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIAID Data Discovery Portal|CIQUAL Food Composition Table 2020. Available online: https://data.niaid.nih.gov/resources?id=zenodo_4770201 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Open Food Facts Global Database. Available online: https://world.openfoodfacts.org (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Bragolusi, M.; Tata, A.; Massaro, A.; Zacometti, C.; Piro, R. Nutritional Labelling of Food Products Purchased from Online Retail Outlets: Screening of Compliance with European Union Tolerance Limits by near Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 2023, 31, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, E.; Lavriša, Ž.; Hribar, M.; Krušič, S.; Kušar, A.; Žmitek, K.; Skrt, M.; Poklar Ulrih, N.; Pravst, I. Verifying the Use of Food Labeling Data for Compiling Branded Food Databases: A Case Study of Sugars in Beverages. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 794468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Food Categories | Indicative Aggregation Descriptors Identified in the Food’s Long Name | Indicative Aggregation Descriptors Identified from Ingredient Lists or Other Characteristics | Example Generic Food Names |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk, milk product or milk substitute | Animal of origin (cow, sheep, goat, donkey, mixed) Processing (pasteurized, UHT, condensed, powder, fermented) Fat content (skimmed, semi-skimmed, full fat or numerical values) Flavored (plain, chocolate, other flavors) | Sweeteners (sugar, non-nutritive sweeteners, honey, juices, jams, purees) Protein fortification (whey, soya, pea) | Yogurt, cow milk, strained, 0% fat, plain Milk, cow, pasteurized, 2% fat, chocolate, with stevia Almond drink, low fat, UHT, chocolate, pea protein fortified, with sweeteners |

| Fat or fat product | Animal or plant (or mixed) Solid, liquid, spreadable | Bioactives (stanols, sterols) Secondary ingredients (yogurt) | Butter, cow, spreadable, unsalted, with yogurt Margarine, sunflower and olive oil mix, spreadable, unsalted, with plant sterols |

| Grain or grain product | Main grain (wheat, oat, spelt, multigrain) Secondary ingredients (nuts, fruits, seeds) Processing (baked, dried, wholegrain) Coatings or fillings | Sweeteners (sugar, non-nutritive sweeteners, honey, juices, jams, purees) Fortification (protein, fiber) | Bread, multigrain, wholegrain, sliced Bread, wheat, white, with glucomannan, sliced Biscuits, wheat, plain, chocolate coating |

| Vegetable or vegetable product | Processing (canned, frozen, dried) Liquid matrix (brine, water, syrup, oil) Secondary ingredients (spices, fillings) | Recommended consumption (with or without liquid matrix) | Spinach, leaves, frozen Mushrooms, shitake, dried, with spices Asparagus, white, in brine, strained Peppers, red, roasted, with cream cheese stuffing, in oil, non-strained |

| Food Categories | N Generic Names | N Generic Names from 1 Product | N Generic Names from 2 Products | N Generic Names from ≥3 Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk, milk product or milk substitute (n = 579) | 157 | 69 | 24 | 64 |

| Egg or egg product (n = 35) | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Meat or meat product (n = 139) | 45 | 24 | 7 | 14 |

| Seafood or related product (n = 73) | 27 | 15 | 4 | 8 |

| Fat or fat product (n = 65) | 22 | 12 | 2 | 8 |

| Grain or grain product (n = 1034) | 255 | 113 | 42 | 100 |

| Nut, seed or kernel (n = 120) | 57 | 31 | 13 | 13 |

| Vegetable or vegetable product (n = 204) | 67 | 31 | 11 | 25 |

| Fruit or fruit product (n = 40) | 25 | 17 | 4 | 4 |

| Sugar or sugar product (n = 354) | 148 | 91 | 23 | 34 |

| Beverage (non-milk) (n = 290) | 78 | 33 | 9 | 36 |

| Miscellaneous food product (n = 389) | 154 | 89 | 31 | 34 |

| Ready-to-eat meals (n = 84) | 72 | 64 | 4 | 4 |

| Total n records | 1112 | 591 | 174 | 347 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vlassopoulos, A.; Xanthopoulou, S.; Eleftheriou, S.; Koutsias, I.; Giannakourou, M.C.; Kanellou, A.; Kapsokefalou, M. A Methodological Framework for Aggregating Branded Food Composition Data in mHealth Nutrition Databases: A Case Presentation. Nutrients 2026, 18, 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020359

Vlassopoulos A, Xanthopoulou S, Eleftheriou S, Koutsias I, Giannakourou MC, Kanellou A, Kapsokefalou M. A Methodological Framework for Aggregating Branded Food Composition Data in mHealth Nutrition Databases: A Case Presentation. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):359. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020359

Chicago/Turabian StyleVlassopoulos, Antonis, Stefania Xanthopoulou, Sofia Eleftheriou, Ioannis Koutsias, Maria C. Giannakourou, Anastasia Kanellou, and Maria Kapsokefalou. 2026. "A Methodological Framework for Aggregating Branded Food Composition Data in mHealth Nutrition Databases: A Case Presentation" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020359

APA StyleVlassopoulos, A., Xanthopoulou, S., Eleftheriou, S., Koutsias, I., Giannakourou, M. C., Kanellou, A., & Kapsokefalou, M. (2026). A Methodological Framework for Aggregating Branded Food Composition Data in mHealth Nutrition Databases: A Case Presentation. Nutrients, 18(2), 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020359