Investigation of Feeding Problems and Their Associated Factors in Children with Developmental Disabilities in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

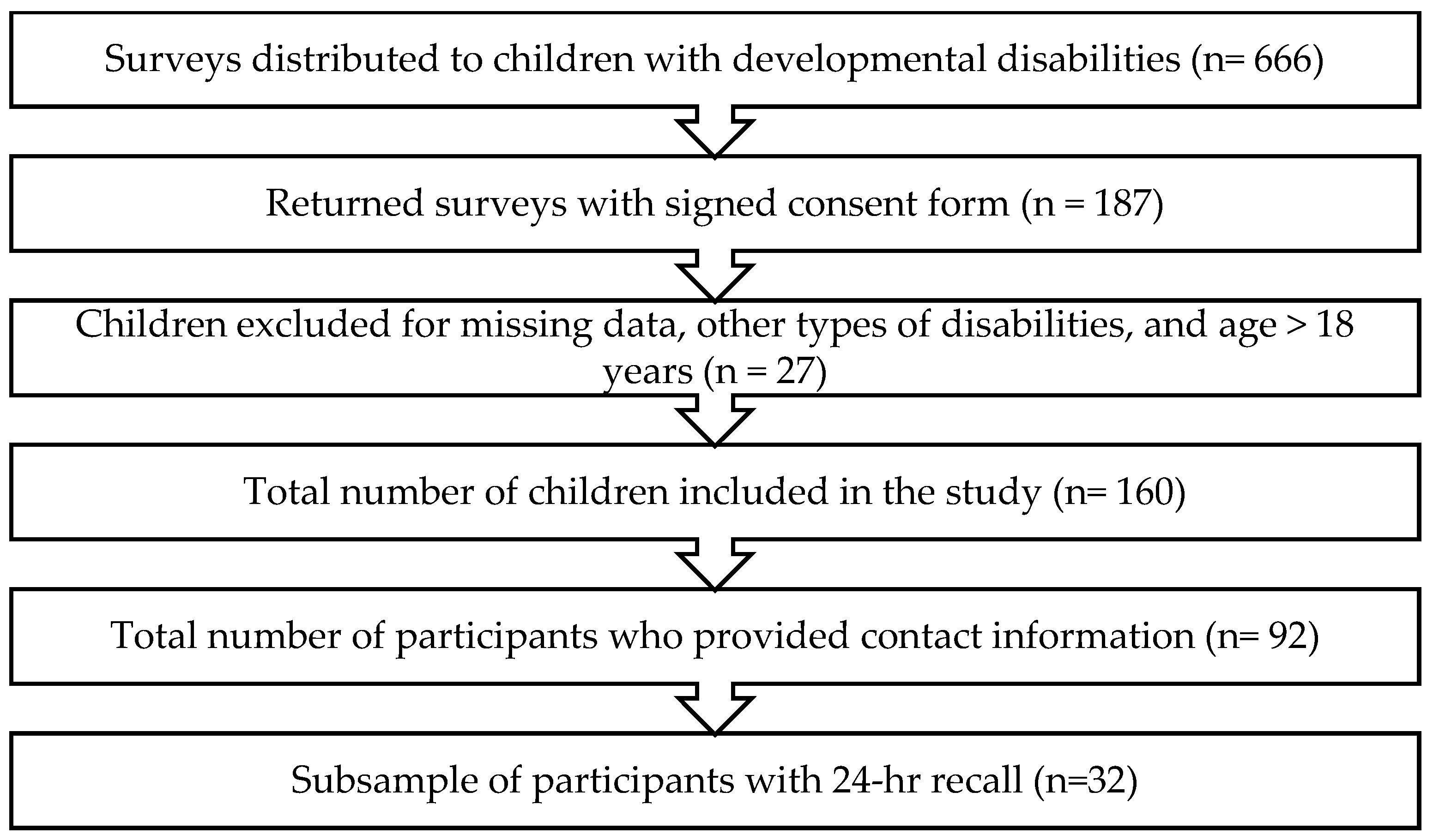

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics of the Study Sample

2.4. Assessment of Feeding Problems

2.5. Assessment of Dietary Quality

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Health-Related Characteristics of the Study Sample

3.3. Feeding Problems

3.4. Association Between Feeding Problems and Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Sample

3.5. Association Between Feeding Problems and Health-Related Characteristics of the Study Sample

3.6. Association Between Feeding Problems and Diet of Children with Developmental Disabilities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DD | Developmental Disabilities |

| STEP-AR | Validated Screening Tool for Eating/Feeding Problems |

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| SFFFQ | Short-Form Food Frequency Questionnaire |

References

- Gordon, R.W. Health, Safety, and Nutrition for the Young Child, Eighth Edition. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 96.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyangar, R. Health maintenance and management in childhood disability. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2002, 13, 793–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaher, S.; Aldhowayan, H.; Almalki, A.; Alsaedi, R.; Almghamsi, R.; Aljazaeri, L.; Mumena, W.A. Investigation of Feeding and Nutritional Problems Related to Long-Term Enteral Nutrition Support among Children with Disabilities: A Pilot Study. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1672436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaher, S.; Ajabnoor, S. Development and Validation of a Questionnaire to Measure Feeding Challenges and Nutritional Problems Associated with Long-Term Enteral Nutrition Among Children With Disabilities. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2025, 18, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.J.; Szatmari, P.; Gaebel, W.; Berk, M.; Vieta, E.; Maj, M.; De Vries, Y.A.; Roest, A.M.; De Jonge, P.; Maercker, A.; et al. Mental, behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders in the ICD-11: An international perspective on key changes and controversies. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO; UNICEF. From the Margins to the Mainstream Global Report on Children with Developmental Disabilities. 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/145016/file/Global-report-on-children-with-developmental-disabilities-2023.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Poulton, A.; Cowell, C.T. Slowing of growth in height and weight on stimulants: A characteristic pattern. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2003, 39, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzer, S.; Skidmore, C.T.; Sperling, M.R. B-vitamin deficiency in patients treated with antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Behav. 2012, 24, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ervin, D.A.; Hennen, B.; Merrick, J.; Morad, M. Healthcare for Persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disability in the Community. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, P.; Shroff, H. The relationship between sensory integration challenges and the dietary intake and nutritional status of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Mumbai, India. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 66, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, M.J.; Sullivan, P.B. Feeding difficulties in disabled children. Paediatr. Child. Health 2010, 20, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.L.; Cooper, C.L.; Mayville, S.B.; González, M.L. The relationship between food refusal and social skills in persons with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 31, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.N. Feeding and Swallowing Issues in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2022, 18, 2311–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCBDDD; CDC. Facts About Intellectual Disability. 2024. Available online: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Hariprasad, P.G.; Elizabeth, K.E.; Valamparampil, M.J.; Kalpana, D.; Anish, T.S. Multiple Nutritional Deficiencies in Cerebral Palsy Compounding Physical and Functional Impairments. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2017, 23, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, S.L.; Stewart, P.A.; Schmidt, B.; Cain, U.; Lemcke, N.; Foley, J.T.; Peck, R.; Clemons, T.; Reynolds, A.; Johnson, C.; et al. Nutrient Intake From Food in Children With Autism. Pediatrics 2012, 130, S145–S153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, H.; Nogay, N.H. Does severity of intellectual disability affect the nutritional status of intellectually disabled children and adolescents? Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 68, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagomez, A.; Ramtekkar, U. Iron, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Zinc Deficiencies in Children Presenting with Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Children 2014, 1, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, Y.; Sergi, C. Feeding Disability in Children. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing LLC: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564306/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Samuel, R.; Manikandan, B.; Russell, P.S.S. Original research: Caregiver experiences of feeding children with developmental disabilities: A qualitative study using interpretative phenomenological analysis from India. BMJ Open 2023, 13, 72714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumena, W.; Kutbi, H. Psychometric Evaluation of the Screening Tool for Feeding Problems (STEP) in Saudi Children with Developmental Disabilities Aged 4-18 Years. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 34, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiverling, L.; Hendy, H.M.; Williams, K. The Screening Tool of Feeding Problems applied to children (STEP-CHILD): Psychometric characteristics and associations with child and parent variables. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleghorn, C.L.; Harrison, R.A.; Ransley, J.K.; Wilkinson, S.; Thomas, J.; Cade, J.E. Can a dietary quality score derived from a short-form FFQ assess dietary quality in UK adult population surveys? Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2915–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumena, W.; Alnezari, A.; Safar, H.; Alharbi, N.; Alahmadi, R.; Qadhi, R.; Faqeeh, S.; Kutbi, H. Media use, dietary intake, and diet quality of adolescents in Saudi Arabia. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 94, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumena, W.; Ateek, A.; Alamri, R.; Alobaid, S.; Alshallali, S.; Afifi, S.; Aljohani, G.; Kutbi, H. Fast-Food Consumption, Dietary Quality, and Dietary Intake of Adolescents in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.C.; Seo, S.M.; Woo, H.S. Effect of oral motor facilitation technique on oral motor and feeding skills in children with cerebral palsy: A case study. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, D.; Garland, M.; Williams, K. Correlates of specific childhood feeding problems. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2003, 39, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, S.; Sciberras, E.; Post, B.; Gerner, B.; Rinehart, N.; Nicholson, J.M.; Evans, S. Experience of stress in parents of children with ADHD: A qualitative study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2019, 14, 1690091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, S.A.; Curtin, C.; Bandini, L.G. Food Selectivity and Sensory Sensitivity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakis, M.; Polychronis, K.; Panagouli, E.; Tzila, E.; Papageorgiou, A.; Thomaidou, L.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A.K. Food Difficulties in Infancy and ASD: A Literature Review. Children 2022, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goday, P.S.; Huh, S.Y.; Silverman, A.; Lukens, C.T.; Dodrill, P.; Cohen, S.S.; Delaney, A.L.; Feuling, M.B.; Noel, R.J.; Gisel, E.; et al. Pediatric Feeding Disorder: Consensus Definition and Conceptual Framework. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeau, M.V.; Richard, E.; Wallace, G.L. The Combination of Food Approach and Food Avoidant Behaviors in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: “Selective Overeating”. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventakou, V.; Micali, N.; Georgiou, V.; Sarri, K.; Koutra, K.; Koinaki, S.; Vassilaki, M.; Kogevinas, M.; Chatzi, L. Is there an association between eating behaviour and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in preschool children? J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Must, A.; Curtin, C.; Hubbard, K.; Sikich, L.; Bedford, J.; Bandini, L. Obesity Prevention for Children with Developmental Disabilities. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2014, 3, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H.A.; Bowling, A.; Santos, S.; Greaves-Lord, K.; Jansen, P.W. Child ADHD and autistic traits, eating behaviours and weight: A population-based study. Pediatr. Obes. 2022, 17, e12951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, N.M.; Bulik, C.M.; Chawner, S.J.R.A.; Micali, N. Prevalence and recurrence of pica behaviors in early childhood within the ALSPAC birth cohort. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 57, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, V.L.; Soke, G.N.; Reynolds, A.; Tian, L.H.; Wiggins, L.; Maenner, M.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Kral, T.V.E.; Hightshoe, K.; Schieve, L.A. Pica, autism, and other disabilities. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e20200462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Leal, K.; Pinto da Costa, M.; Vilela, S. Socioeconomic and household framework influences in school-aged children’s eating habits: Understanding the parental roles. Appetite 2024, 201, 107605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Ansem, W.J.C.; Schrijvers, C.T.M.; Rodenburg, G.; van de Mheen, D. Maternal educational level and children’s healthy eating behaviour: Role of the home food environment (cross-sectional results from the INPACT study). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoke, M.J.; Umoke, P.C.I.; Onyeke, N.G.; Victor-Aigbodion, V.; Eseadi, C.; Ebizie, E.N.; Obiweluozo, P.E.; Uzodinma, U.E.; Chukwuone, C.A.; Dimelu, I.N.; et al. Influence of parental education levels on eating habits of pupils in Nigerian primary schools. Medicine 2020, 99, e22953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubel, J.; Martin, S.L.; Cunningham, K. Introduction: A family systems approach to promote maternal, child and adolescent nutrition. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2021, 17, e13228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, Y.; Jansen, P.W.; Raat, H.; Nguyen, A.N.; Voortman, T. Associations of family feeding and mealtime practices with children’s overall diet quality: Results from a prospective population-based cohort. Appetite 2021, 160, 105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Martin, A.; Arreola, V.; Riera, S.A.; Pizarro, A.; Carol, C.; Serras, L.; Clavé, P. Assessment of swallowing disorders, nutritional and hydration status, and oral hygiene in students with severe neurological disabilities including cerebral palsy. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver’s relationship with child | ||

| Mother | 139 | 86.9 |

| Father | 14 | 8.80 |

| Sibling | 3 | 1.90 |

| Others | 4 | 2.50 |

| Caregiver’s age group | ||

| 20–30 years | 31 | 19.4 |

| 31–40 years | 76 | 47.5 |

| >40 years | 53 | 33.1 |

| Caregiver’s education level | ||

| <High school | 45 | 28.1 |

| High school/Diploma | 41 | 25.6 |

| Bachelor | 67 | 41.9 |

| Postgraduate degree | 7 | 4.40 |

| Caregiver’s marital status | ||

| Married | 131 | 81.9 |

| Single | 29 | 18.1 |

| Family monthly income 1 | ||

| <SAR 4000 | 41 | 25.6 |

| SAR 4000–6000 | 46 | 28.8 |

| SAR 6001–10,000 | 34 | 21.3 |

| SAR 10,001–15,000 | 27 | 16.9 |

| >SAR 15,000 | 12 | 7.50 |

| Gender | ||

| Boy | 92 | 57.5 |

| Girl | 68 | 42.5 |

| Age group | ||

| 1–3 years | 9 | 5.60 |

| 4–8 years | 73 | 45.6 |

| 9–13 years | 56 | 35.0 |

| 14–18 years | 22 | 13.8 |

| Nationality | ||

| Saudi | 143 | 89.4 |

| Non-Saudi | 17 | 10.6 |

| Order of child | ||

| Only child | 18 | 11.3 |

| Oldest child | 37 | 23.1 |

| Middle child | 42 | 26.3 |

| Youngest child | 63 | 39.4 |

| Living arrangement | ||

| Live with both parents | 133 | 83.1 |

| Live with mother | 19 | 11.9 |

| Live with father | 4 | 2.50 |

| Live with other family member or live in disability center | 4 | 2.50 |

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Type of disability | ||

| ADHD | 35 | 21.9 |

| ASD | 44 | 27.5 |

| Cerebral palsy | 22 | 13.8 |

| Intellectual disability | 21 | 13.1 |

| Learning disability | 25 | 15.6 |

| Down syndrome | 10 | 6.30 |

| Other | 3 | 1.90 |

| Other medical conditions | ||

| No | 115 | 71.9 |

| Yes | 45 | 28.1 |

| Untreated dental problem | ||

| No | 90 | 56.3 |

| Yes | 70 | 43.8 |

| Medication use | ||

| No | 129 | 80.6 |

| Yes | 31 | 19.4 |

| Structured physical activity | ||

| No | 119 | 74.4 |

| Yes | 41 | 25.6 |

| Independency | ||

| No | 88 | 55.0 |

| Yes | 72 | 45.0 |

| Sleep time | ||

| Adequate sleep | 61 | 38.1 |

| Inadequate sleep | 99 | 61.9 |

| Screen time | ||

| ≤2 h/d | 102 | 63.8 |

| >2 h/d | 58 | 36.3 |

| Food allergies | ||

| No | 146 | 91.3 |

| Yes | 14 | 8.80 |

| Dietitian visit | ||

| No | 123 | 76.9 |

| Yes | 37 | 23.1 |

| Supplement use | ||

| No | 113 | 70.6 |

| Yes | 47 | 29.4 |

| Nutritional drink use | ||

| No | 144 | 90.0 |

| Yes | 16 | 10.0 |

| Subdomain | Never | Yes, Occurring Between 1 and 10 Times in the Last Month | Yes, More Than 10 Times in the Last Month | Incidence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes No Problems | Causes Minimal Harm | Causes Serious Harm | Causes No Problems | Causes Minimal Harm | Causes Serious Harm | ||||

| Aspiration Risk | He/she regurgitates and re-swallows food either during or immediately following meals | 137 (85.6) | 14 (8.75) | 4 (2.50) | 1 (0.63) | 3 (1.88) | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 14.3% |

| He/she vomits either during or immediately following meals | 148 (92.5) | 5 (3.13) | 4 (2.50) | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 7.5% | |

| Refusal | Problem behaviors (e.g., aggression, SIB) increase during mealtimes | 141 (88.1) | 10 (6.25) | 6 (3.75) | 2 (1.25) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 11.8% |

| He/she spits out their food before swallowing | 137 (85.6) | 13 (8.13) | 5 (3.13) | 1 (0.63) | 3 (1.88) | 1 (0.063) | 0 (0.00) | 14.3% | |

| He/she pushes food away or attempts to leave the area when food is presented | 116 (72.5) | 23 (14.4) | 11 (6.88) | 1 (0.63) | 3 (1.88) | 5 (3.13) | 1 (0.63) | 27.5% | |

| Selectivity | He/she will only eat selected types of food (e.g., pudding, rice) | 117 (73.1) | 27 (16.9) | 4 (2.50) | 1 (0.63) | 8 (5.00) | 2 (1.25) | 1 (0.63) | 26.8% |

| He/she prefers a certain setting for eating (e.g., bedroom, dining room) | 133 (83.1) | 13 (8.13) | 2 (1.25) | 1 (0.63) | 9 (5.63) | 2 (1.25) | 0 (0.00) | 16.8% | |

| He/she prefers to be fed by a specific caregiver or prefers to be fed rather than feed himself/herself | 111 (69.4) | 33 (20.6) | 5 (3.13) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (2.50) | 5 (3.13) | 2 (1.25) | 30.6% | |

| He/she only eats foods of certain textures | 114 (71.3) | 25 (15.6) | 8 (5.00) | 1 (0.63) | 8 (5.00) | 3 (1.88) | 1 (0.63) | 28.7% | |

| Nutrition Behaviors | He/she eats or attempts to eat items that are not food | 110 (68.8) | 29 (18.1) | 9 (5.63) | 2 (1.25) | 5 (3.13) | 4 (2.50) | 1 (0.63) | 31.2% |

| He/she only eats a small amount of the food presented to him or her | 119 (74.3) | 22 (13.7) | 4 (2.50) | 1 (0.63) | 6 (3.75) | 7 (4.38) | 1 (0.63) | 25.6% | |

| He/she will continue to eat as long as food is available | 107 (66.8) | 33 (20.6) | 10 (6.25) | 2 (1.25) | 5 (3.13) | 2 (1.25) | 1 (0.63) | 33.1% | |

| Skills | He/she cannot feed him/herself independently | 97 (60.6) | 35 (21.8) | 13 (8.13) | 5 (3.13) | 9 (5.63) | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 39.3% |

| He/she does not demonstrate the ability to chew | 114 (71.2) | 27 (16.8) | 9 (5.63) | 1 (0.63) | 6 (3.75) | 3 (1.88) | 0 (0.00) | 28.7% | |

| He/she chokes on food | 138 (86.2) | 11 (6.88) | 4 (2.50) | 3 (1.88) | 2 (1.25) | 2 (1.25) | 0 (0.00) | 13.7% | |

| He/she does not demonstrate the ability to swallow | 126 (78.7) | 17 (10.6) | 6 (3.75) | 2 (1.25) | 8 (5.00) | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 21.2% | |

| He/she eats a large amount of food in a short period of time | 122 (76.2) | 21 (13.1) | 7 (4.38) | 1 (0.63) | 5 (3.13) | 3 (1.88) | 1 (0.63) | 23.7% | |

| Variable | Beta | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | R-Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver’s relationship with child (Mother = 1; Father = 2; Sibling = 3; Others = 4) | 2.79 | 0.94 | 0.004 * | 0.93 to 4.65 | 0.06 |

| Caregiver’s age group (20–30 years = 1; 31–40 years = 2; >40 years = 3) | −0.69 | 0.81 | 0.399 | −2.29 to 0.92 | 0.01 |

| Caregiver’s education level (<High school = 1; High school/diploma = 2; Bachelor = 3; Postgraduate degree = 4) | 1.81 | 0.62 | 0.004 * | 0.58 to 3.04 | 0.05 |

| Caregiver’s marital status (Married = 1; Single = 2) | 0.99 | 1.49 | 0.507 | −1.95 to 3.93 | 0.01 |

| Family monthly income (<SAR 4000 = 1; SAR 4000–6000 = 2; SAR 6001–10,000 = 3; SAR 10,001–15,000 = 4; >SAR 15,000 = 5) | 1.04 | 0.45 | 0.023 * | 0.15 to 1.93 | 0.04 |

| Other children with disability (No = 0; Yes = 1) | 0.36 | 1.63 | 0.824 | −2.86 to 3.58 | 0.00 |

| Children’s gender (Boy = 1; Girl = 2) | 0.57 | 1.17 | 0.625 | −1.74 to 2.88 | 0.00 |

| Children’s age group (1–3 years = 1; 4–8 years = 2; 9–13 years = 3; 14–18 years = 4) | 0.06 | 0.72 | 0.937 | −1.37 to 1.49 | 0.00 |

| Nationality | −0.25 | 1.91 | 0.895 | −4.03 to 3.52 | 0.00 |

| Order of child (Only child = 1; Oldest child = 2; Middle child = 3; Youngest child = 4) | −0.73 | 0.55 | 0.189 | −1.82 to 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Living arrangement (Live with both parents = 1; Live with mother = 2; Live with father = 3; Live with other family member or in disability center = 4) | 2.37 | 0.90 | 0.009 * | 0.59 to 4.15 | 0.05 |

| Variable | Beta | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | R-Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet quality score | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.622 | −0.03 to 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Water, cup/d | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.051 | −0.09 to −0.00 | 0.12 |

| Energy, kcal/d | 2.33 | 20.5 | 0.911 | −39.9 to 44.6 | 0.08 |

| Carbohydrate, g/d | −1.38 | 3.06 | 0.656 | −7.69 to 4.93 | 0.06 |

| Protein, g/d | 0.54 | 1.86 | 0.775 | −3.28 to 4.35 | 0.15 |

| Fat, g/d | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.763 | −1.62 to 2.18 | 0.12 |

| Fiber, g/d | 0.29 | 0.56 | 0.614 | −0.86 to 1.43 | 0.16 |

| Free sugar, g/d | 1.18 | 2.26 | 0.606 | −3.47 to 5.83 | 0.31 |

| Sodium | −286 | 160 | 0.085 | −614 to 42.5 | 0.17 |

| Potassium | −0.94 | 37.8 | 0.980 | −78.7 to 76.8 | 0.00 |

| Calcium | −1.12 | 12.3 | 0.928 | 26.4 to 24.2 | 0.04 |

| Phosphorus | −6.40 | 12.80 | 0.621 | −32.71 to 19.91 | 0.04 |

| Magnesium | −1.11 | 2.46 | 0.657 | −6.17 to 3.96 | 0.20 |

| Iron | −0.01 | 0.20 | 0.970 | −0.42 to 0.40 | 0.02 |

| Zinc | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.586 | −0.26 to 0.15 | 0.08 |

| Copper | −0.29 | 0.55 | 0.602 | −1.43 to 0.84 | 0.07 |

| Manganese | 0.29 | 2.90 | 0.920 | −5.67 to 6.26 | 0.16 |

| Selenium | −0.07 | 1.29 | 0.955 | −2.72 to 2.57 | 0.06 |

| Iodine | −0.80 | 1.22 | 0.516 | −3.31 to 1.70 | 0.08 |

| Vitamin D | 0.60 | 1.50 | 0.694 | −2.50 to 3.69 | 0.09 |

| Vitamin E | −0.04 | 0.13 | 0.784 | −0.30 to 0.23 | 0.05 |

| Vitamin B12 | −0.003 | 0.19 | 0.988 | −0.39 to 0.39 | 0.07 |

| Vitamin C | 0.03 | 1.55 | 0.987 | −3.15 to 3.21 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mumena, W.A.; Zaher, S.; Althowebi, M.; Alharbi, M.; Alharbi, R.; Aloufi, M.; Alqurashi, N.; Qadhi, R.; Faqeeh, S.; Alnezari, A.; et al. Investigation of Feeding Problems and Their Associated Factors in Children with Developmental Disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Nutrients 2026, 18, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020356

Mumena WA, Zaher S, Althowebi M, Alharbi M, Alharbi R, Aloufi M, Alqurashi N, Qadhi R, Faqeeh S, Alnezari A, et al. Investigation of Feeding Problems and Their Associated Factors in Children with Developmental Disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020356

Chicago/Turabian StyleMumena, Walaa Abdullah, Sara Zaher, Maha Althowebi, Manar Alharbi, Reuof Alharbi, Maram Aloufi, Najlaa Alqurashi, Rana Qadhi, Sawsan Faqeeh, Arwa Alnezari, and et al. 2026. "Investigation of Feeding Problems and Their Associated Factors in Children with Developmental Disabilities in Saudi Arabia" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020356

APA StyleMumena, W. A., Zaher, S., Althowebi, M., Alharbi, M., Alharbi, R., Aloufi, M., Alqurashi, N., Qadhi, R., Faqeeh, S., Alnezari, A., Aljohani, G. A., & Kutbi, H. A. (2026). Investigation of Feeding Problems and Their Associated Factors in Children with Developmental Disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Nutrients, 18(2), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020356