Intestine-Specific Ferroportin Ablation Rescues from Systemic Iron Overload in Mice

Abstract

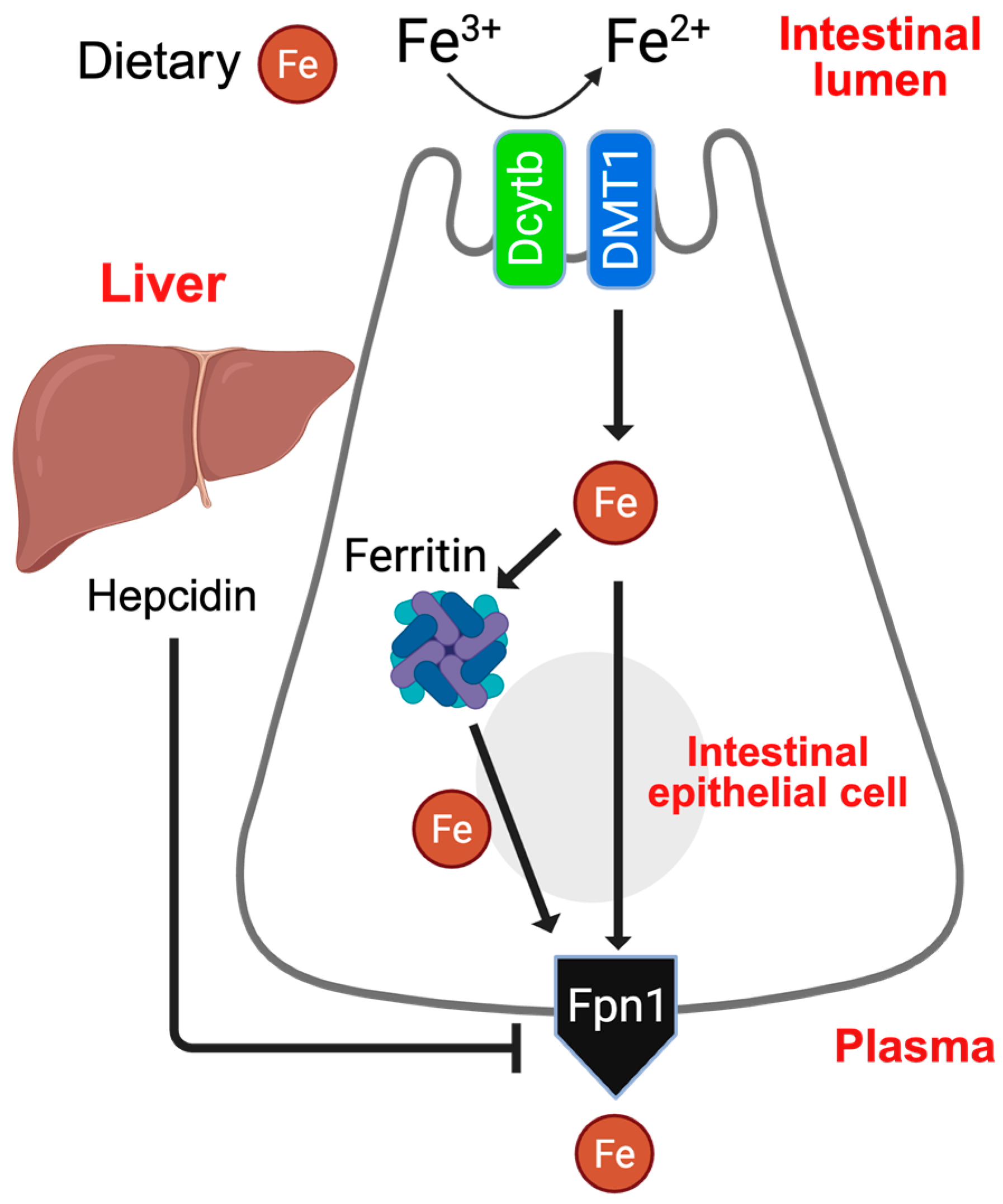

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Treatments

2.2. CRISPR-Mediated Hepcidin-KO Model

2.3. Antibodies

2.4. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

2.5. Western Blotting

2.6. Tissue Iron Analysis by ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry)

2.7. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

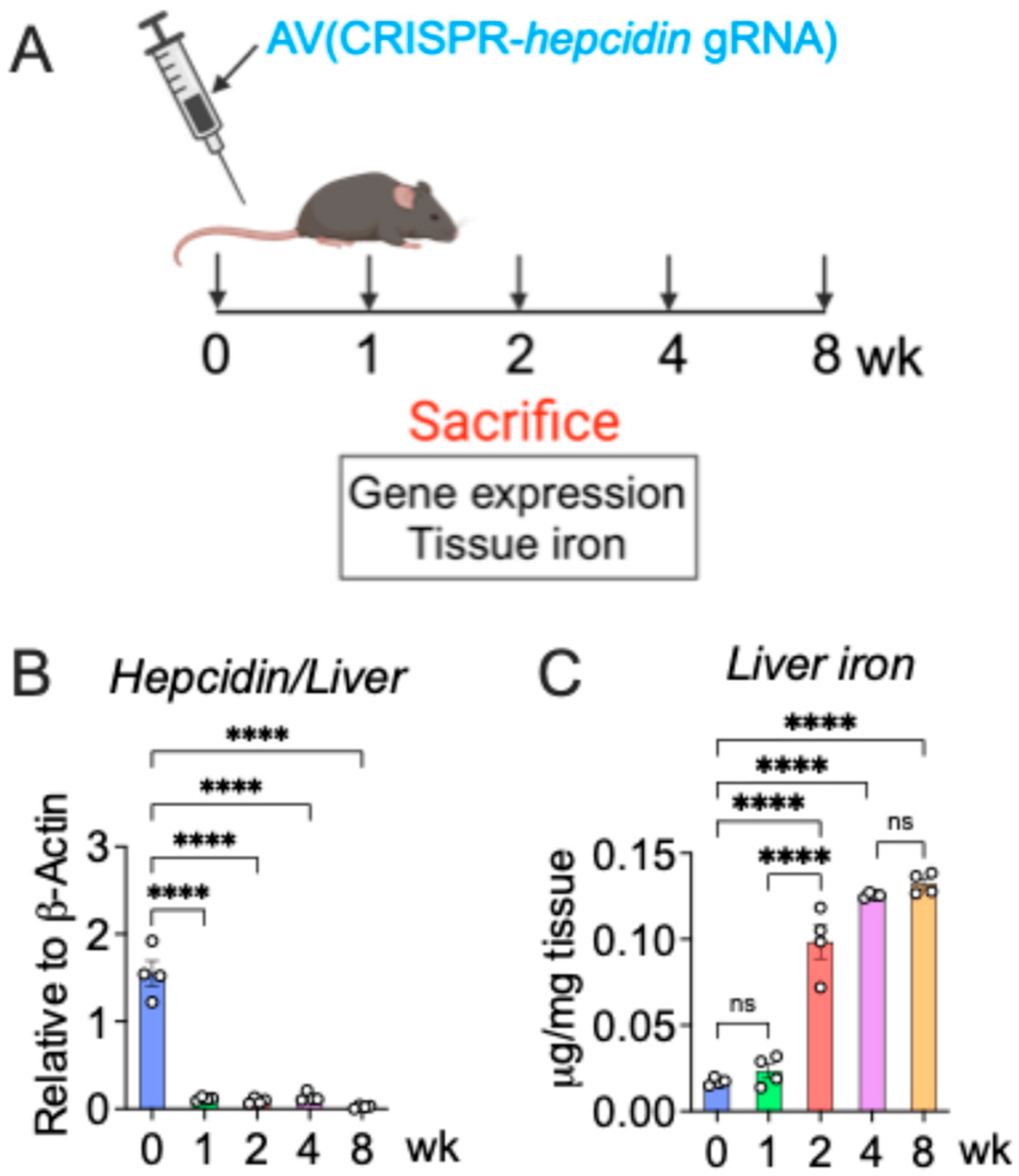

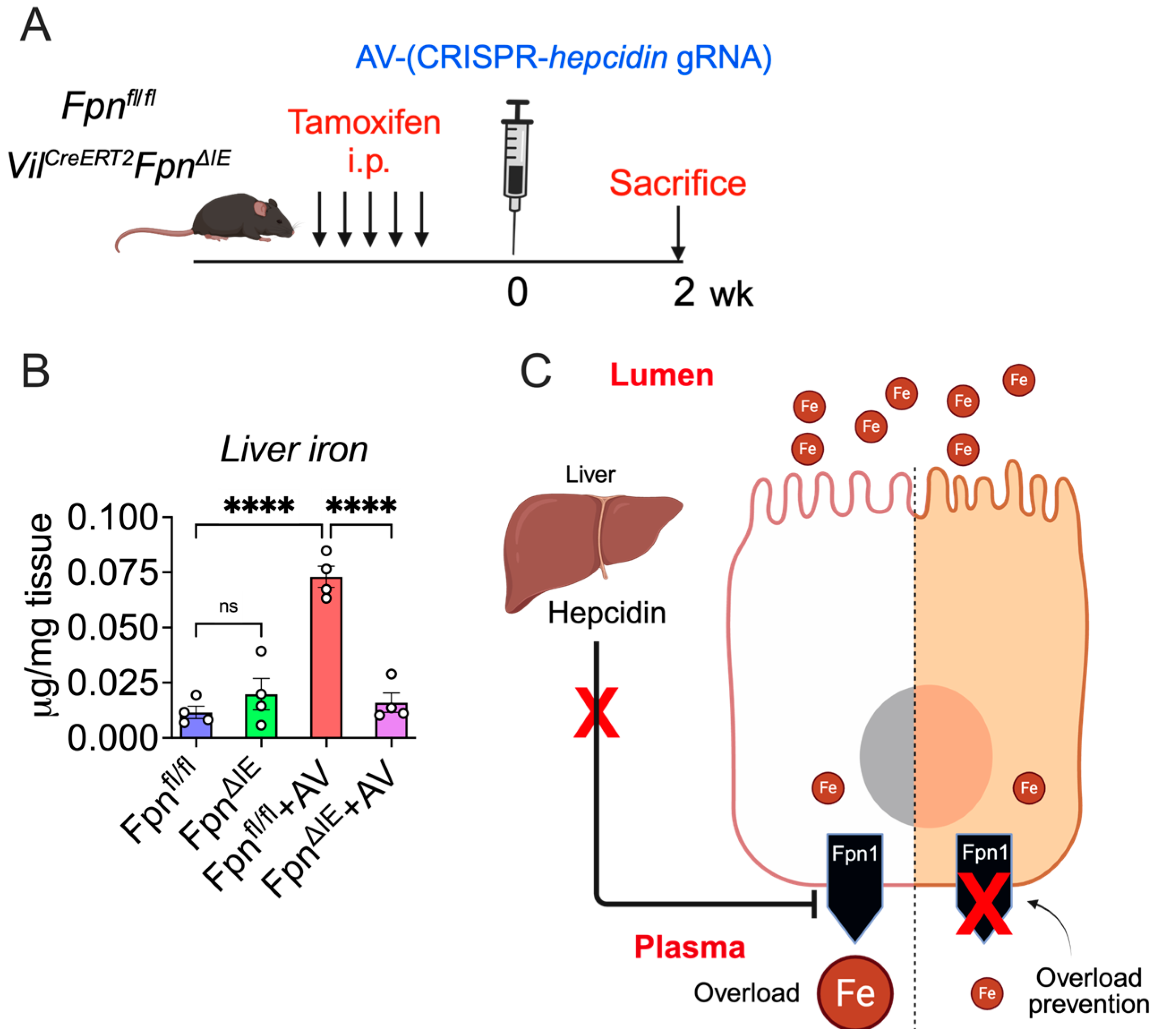

3.1. A Cre-Independent Iron Overload Model via Adenovirus-Mediated Rapid and Durable Hepcidin KO

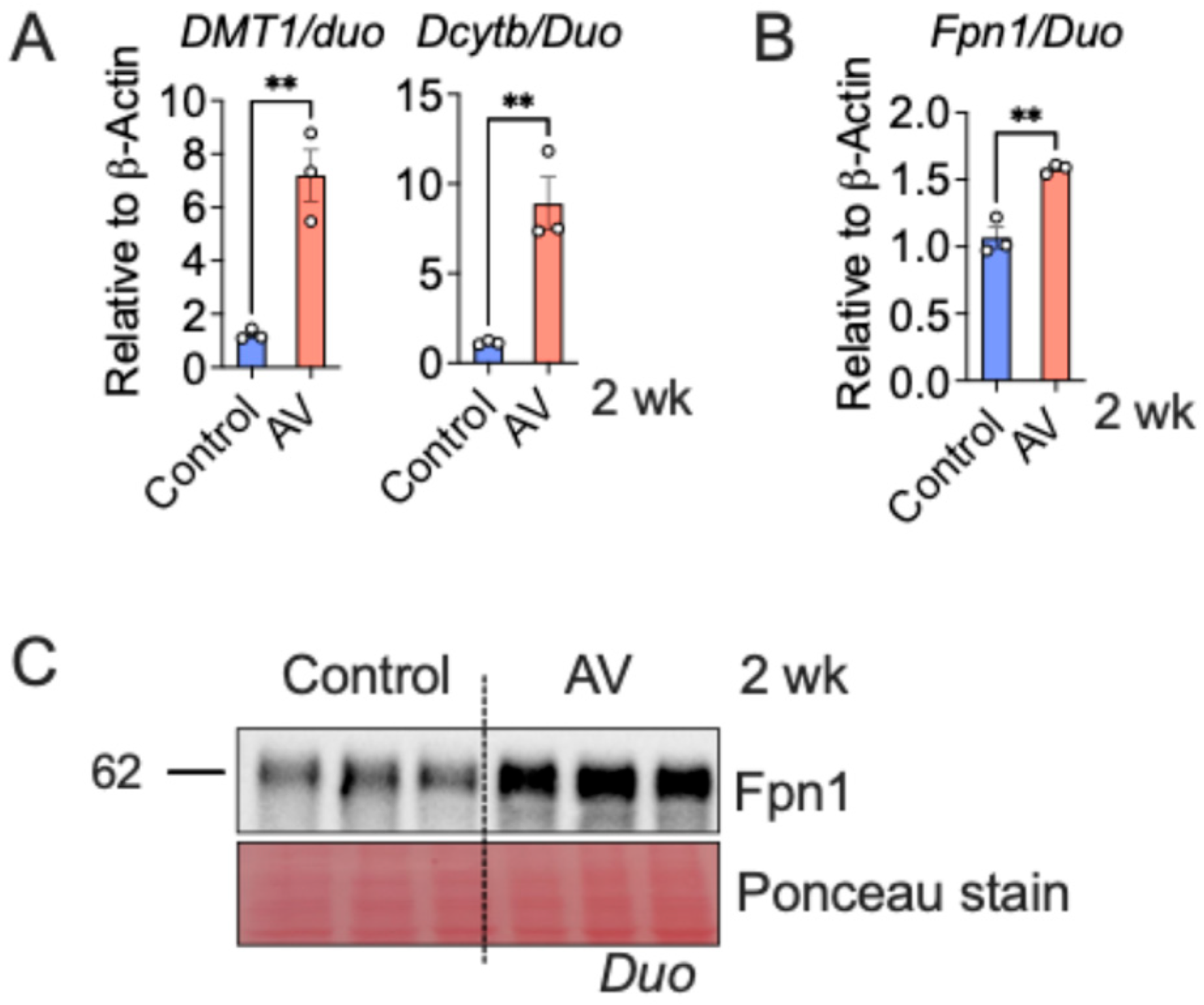

3.2. AV-Hepc KO Activates the Enterocyte Iron Transport Machinery

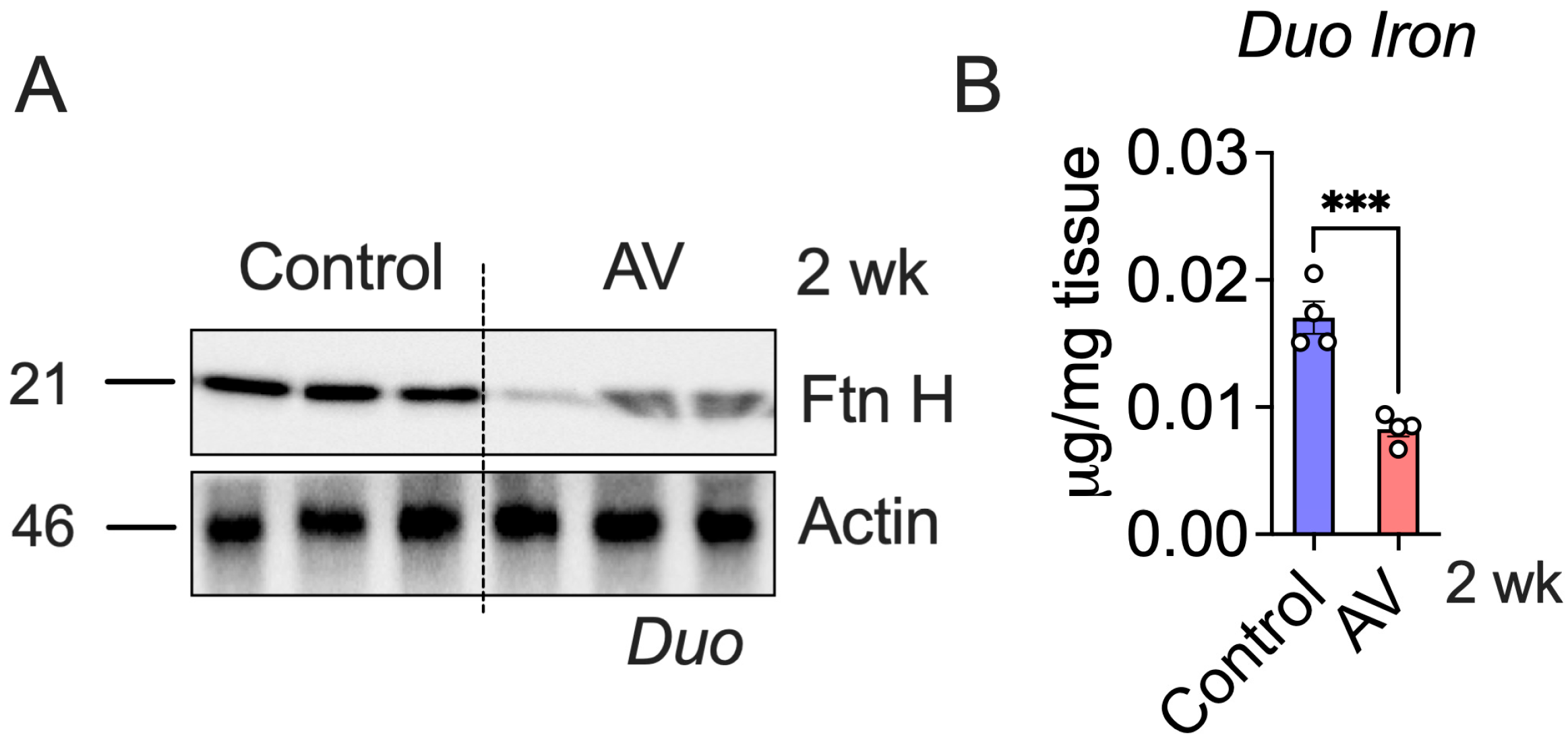

3.3. AV-Hepc KO Leads to Enterocyte Iron Depletion

3.4. Intestine-Specific Fpn1 Ablation Prevents Hepc KO-Mediated Iron Overload

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| HIF | Hypoxia Inducible Factor |

| Ftn | Ferritin |

| Fpn | Ferroportin |

References

- Anderson, G.J.; Frazer, D.M. Current understanding of iron homeostasis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1559S–1566S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, S.; Hamza, I.; Bartnikas, T.B. Molecular Mechanisms of Iron and Heme Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2022, 42, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muckenthaler, M.U.; Rivella, S.; Hentze, M.W.; Galy, B. A Red Carpet for Iron Metabolism. Cell 2017, 168, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.; Faustino, P. An overview of molecular basis of iron metabolism regulation and the associated pathologies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Res. 2015, 1852, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.M.; Matsubara, T.; Ito, S.; Yim, S.H.; Gonzalez, F.J. Intestinal hypoxia-inducible transcription factors are essential for iron absorption following iron deficiency. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin Interaction Controls Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginzburg, Y.Z. Hepcidin-ferroportin axis in health and disease. Vitam. Horm. 2019, 110, 17–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica 2020, 105, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Senussi, N.H.; Fertrin, K.Y.; Kowdley, K.V. Iron overload disorders. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 1842–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangelo, A. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Res. 2006, 1763, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, A.; Lima, C.A.; Pinkus, J.L.; Pinkus, G.S.; Zon, L.I.; Robine, S.; Andrews, N.C. The iron exporter ferroportin/Slc40a1 is essential for iron homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005, 1, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakesmith, H.; Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Ironing out Ferroportin. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1823, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantopoulos, K. Inherited Disorders of Iron Overload. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Hepcidin and disorders of iron metabolism. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangelo, A. Ferroportin disease: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1972–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, G.; Ganz, T.; Goodnough, L.T. Anemia of inflammation. Blood 2019, 133, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.J.; Das, N.K.; Ramakrishnan, S.K.; Jain, C.; Jurkovic, M.T.; Wu, J.; Nemeth, E.; Lakhal-Littleton, S.; Colacino, J.A.; Shah, Y.M. Hepatic hepcidin/intestinal HIF-2alpha axis maintains iron absorption during iron deficiency and overload. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.K.; Jain, C.; Sankar, A.; Schwartz, A.J.; Santana-Codina, N.; Solanki, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Parimi, S.; Rui, L.; et al. Modulation of the HIF2alpha-NCOA4 axis in enterocytes attenuates iron loading in a mouse model of hemochromatosis. Blood 2022, 139, 2547–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.K.; Schwartz, A.J.; Barthel, G.; Inohara, N.; Liu, Q.; Sankar, A.; Hill, D.R.; Ma, X.; Lamberg, O.; Schnizlein, M.K.; et al. Microbial Metabolite Signaling Is Required for Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 115–130.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.R.; Taylor, M.; Xue, X.; Ramakrishnan, S.K.; Martin, A.; Xie, L.; Bredell, B.X.; Gardenghi, S.; Rivella, S.; Shah, Y.M. Intestinal HIF2alpha promotes tissue-iron accumulation in disorders of iron overload with anemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E4922–E4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Standard deviations and standard errors. bmj 2005, 331, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyffenegger, N.; Flace, A.; Varol, A.; Altermatt, P.; Doucerain, C.; Sundstrom, H.; Dürrenberger, F.; Manolova, V. The oral ferroportin inhibitor vamifeport prevents liver iron overload in a mouse model of hemochromatosis. Hemasphere 2024, 8, e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.; Taher, A.; Viprakasit, V.; Kattamis, A.; Coates, T.D.; Garbowski, M.; Dürrenberger, F.; Manolova, V.; Richard, F.; Cappellini, M.D. Oral ferroportin inhibitor vamifeport for improving iron homeostasis and erythropoiesis in beta-thalassemia: Current evidence and future clinical development. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2021, 14, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin and Iron in Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 2023, 74, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Tuttle, M.S.; Powelson, J.; Vaughn, M.B.; Donovan, A.; Ward, D.M.; Ganz, T.; Kaplan, J. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science 2004, 306, 2090–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.F.; Frazer, D.M.; Faria, N.; Bruggraber, S.F.; Wilkins, S.J.; Mirciov, C.; Powell, J.J.; Anderson, G.J.; Pereira, D.I.A. Ferroportin mediates the intestinal absorption of iron from a nanoparticulate ferritin core mimetic in mice. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 3671–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Protchenko, O.; Huber, K.D.; Shakoury-Elizeh, M.; Ghosh, M.C.; Philpott, C.C. The iron chaperone poly(rC)-binding protein 1 regulates iron efflux through intestinal ferroportin in mice. Blood 2023, 142, 1658–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.J.; Converso-Baran, K.; Michele, D.E.; Shah, Y.M. A genetic mouse model of severe iron deficiency anemia reveals tissue-specific transcriptional stress responses and cardiac remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 14991–15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunez, M.T.; Tapia, V.; Rojas, A.; Aguirre, P.; Gomez, F.; Nualart, F. Iron supply determines apical/basolateral membrane distribution of intestinal iron transporters DMT1 and ferroportin 1. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010, 298, C477–C485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Qu, A.; Anderson, E.R.; Matsubara, T.; Martin, A.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Shah, Y.M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha mediates the adaptive increase of intestinal ferroportin during iron deficiency in mice. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 2044–2055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.J.; Goyert, J.W.; Solanki, S.; Kerk, S.A.; Chen, B.; Castillo, C.; Hsu, P.P.; Do, B.T.; Singhal, R.; Dame, M.K.; et al. Hepcidin sequesters iron to sustain nucleotide metabolism and mitochondrial function in colorectal cancer epithelial cells. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessman, N.J.; Mathieu, J.R.R.; Renassia, C.; Zhou, L.; Fung, T.C.; Fernandez, K.C.; Austin, C.; Moeller, J.B.; Zumerle, S.; Louis, S.; et al. Dendritic cell-derived hepcidin sequesters iron from the microbiota to promote mucosal healing. Science 2020, 368, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.C.; Ryan, J.D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hemochromatosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 23, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.; Pantopoulos, K. Hepcidin Therapeutics. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowdley, K.V.; Brown, K.E.; Ahn, J.; Sundaram, V. ACG Clinical Guideline: Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 1202–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.J.; Fleming, M.D. Modulation of hepcidin as therapy for primary and secondary iron overload disorders: Preclinical models and approaches. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 28, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolas, G.; Viatte, L.; Lou, D.Q.; Bennoun, M.; Beaumont, C.; Kahn, A.; Andrews, N.C.; Vaulont, S. Constitutive hepcidin expression prevents iron overload in a mouse model of hemochromatosis. Nat. Genet. 2003, 34, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preza, G.C.; Ruchala, P.; Pinon, R.; Ramos, E.; Qiao, B.; Peralta, M.A.; Sharma, S.; Waring, A.; Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Minihepcidins are rationally designed small peptides that mimic hepcidin activity in mice and may be useful for the treatment of iron overload. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4880–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, E.; Ruchala, P.; Goodnough, J.B.; Kautz, L.; Preza, G.C.; Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Minihepcidins prevent iron overload in a hepcidin-deficient mouse model of severe hemochromatosis. Blood 2012, 120, 3829–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casu, C.; Nemeth, E.; Rivella, S. Hepcidin agonists as therapeutic tools. Blood 2018, 131, 1790–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowdley, K.V.; Modi, N.B.; Peltekian, K.; Vierling, J.M.; Ferris, C.; Valone, F.H.; Gupta, S. Rusfertide for the treatment of iron overload in HFE-related haemochromatosis: An open-label, multicentre, proof-of-concept phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleda, N.; Flace, A.; Altermatt, P.; Ingoglia, G.; Doucerain, C.; Nyffenegger, N.; Dürrenberger, F.; Manolova, V. Ferroportin inhibitor vamifeport ameliorates ineffective erythropoiesis in a mouse model of beta-thalassemia with blood transfusions. Haematologica 2023, 108, 2703–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasveld, L.T.; Janssen, R.; Bardou-Jacquet, E.; Venselaar, H.; Hamdi-Roze, H.; Drakesmith, H.; Swinkels, D.W. Twenty Years of Ferroportin Disease: A Review or An Update of Published Clinical, Biochemical, Molecular, and Functional Features. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, E. Anti-hepcidin therapy for iron-restricted anemias. Blood 2013, 122, 2929–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, M.; Asperti, M.; Ruzzenenti, P.; Regoni, M.; Arosio, P. Hepcidin antagonists for potential treatments of disorders with hepcidin excess. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theurl, I.; Schroll, A.; Sonnweber, T.; Nairz, M.; Theurl, M.; Willenbacher, W.; Eller, K.; Wolf, D.; Seifert, M.; Sun, C.C.; et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of hepcidin expression reverses anemia of chronic inflammation in rats. Blood 2011, 118, 4977–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Melgar-Bermudez, E.; Welch, D.; Dagbay, K.B.; Bhattacharya, S.; Lema, E.; Daman, T.; Sierra, O.; Todorova, R.; Drame, P.M.; et al. A Recombinant Antibody Against ALK2 Promotes Tissue Iron Redistribution and Contributes to Anemia Resolution in a Mouse Model of Anemia of Inflammation. Am. J. Hematol. 2025, 100, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, E.; Sugianto, P.; Hsu, J.; Damoiseaux, R.; Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. High-throughput screening of small molecules identifies hepcidin antagonists. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 83, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Castillo, C.; Gim, S.; Das, N.K. Intestine-Specific Ferroportin Ablation Rescues from Systemic Iron Overload in Mice. Nutrients 2026, 18, 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020352

Castillo C, Gim S, Das NK. Intestine-Specific Ferroportin Ablation Rescues from Systemic Iron Overload in Mice. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020352

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastillo, Cristina, Sharon Gim, and Nupur K. Das. 2026. "Intestine-Specific Ferroportin Ablation Rescues from Systemic Iron Overload in Mice" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020352

APA StyleCastillo, C., Gim, S., & Das, N. K. (2026). Intestine-Specific Ferroportin Ablation Rescues from Systemic Iron Overload in Mice. Nutrients, 18(2), 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020352