Distinct Gut Microbiome Profiles Underlying Cardiometabolic Risk Phenotypes in Individuals with Obesity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Age between 35 and 74 years;

- Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2;

- Presence of prediabetes, defined as fasting plasma glucose levels between 6.1 and 6.9 mmol/L, 2 h plasma glucose values between 7.8 and 11.0 mmol/L during a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and/or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels between 5.7% and 6.4%;

- Newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus, defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, 2 h plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L during OGTT, and/or HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, in the absence of antidiabetic therapy.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Evidence of liver dysfunction, defined as serum liver enzyme levels ≥ three times above the upper limit of the reference range;

- Chronic kidney disease stages III–IV;

- Heart failure classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classes III–IV;

- Active or previous neoplastic disease;

- Use of antibiotics within the previous three months prior to enrollment;

- Use of probiotics, prebiotics, or synbiotics within the previous three months prior to enrollment;

- Current or prior use of metformin or other glucose-lowering medications within the previous three months in order to avoid pharmacological confounding of metabolic and gut microbiome outcomes.

2.3. Anthropometric Parameters

- For males:

- For females:

2.4. Assessment of Glycemic Homeostasis

2.5. Definition of Metabolic Syndrome

- Fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L;

- Blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or current antihypertensive treatment;

- Triglyceride levels ≥ 1.7 mmol/L;

- HDL cholesterol ≤ 1.03 mmol/L in men and ≤1.29 mmol/L in women.

2.6. Assessment of Dietary Habits

2.7. Gut Microbiome Analysis by Multiplex Real-Time PCR

2.8. Principle of the Method

2.9. Procedure

2.10. Statistical Analysis

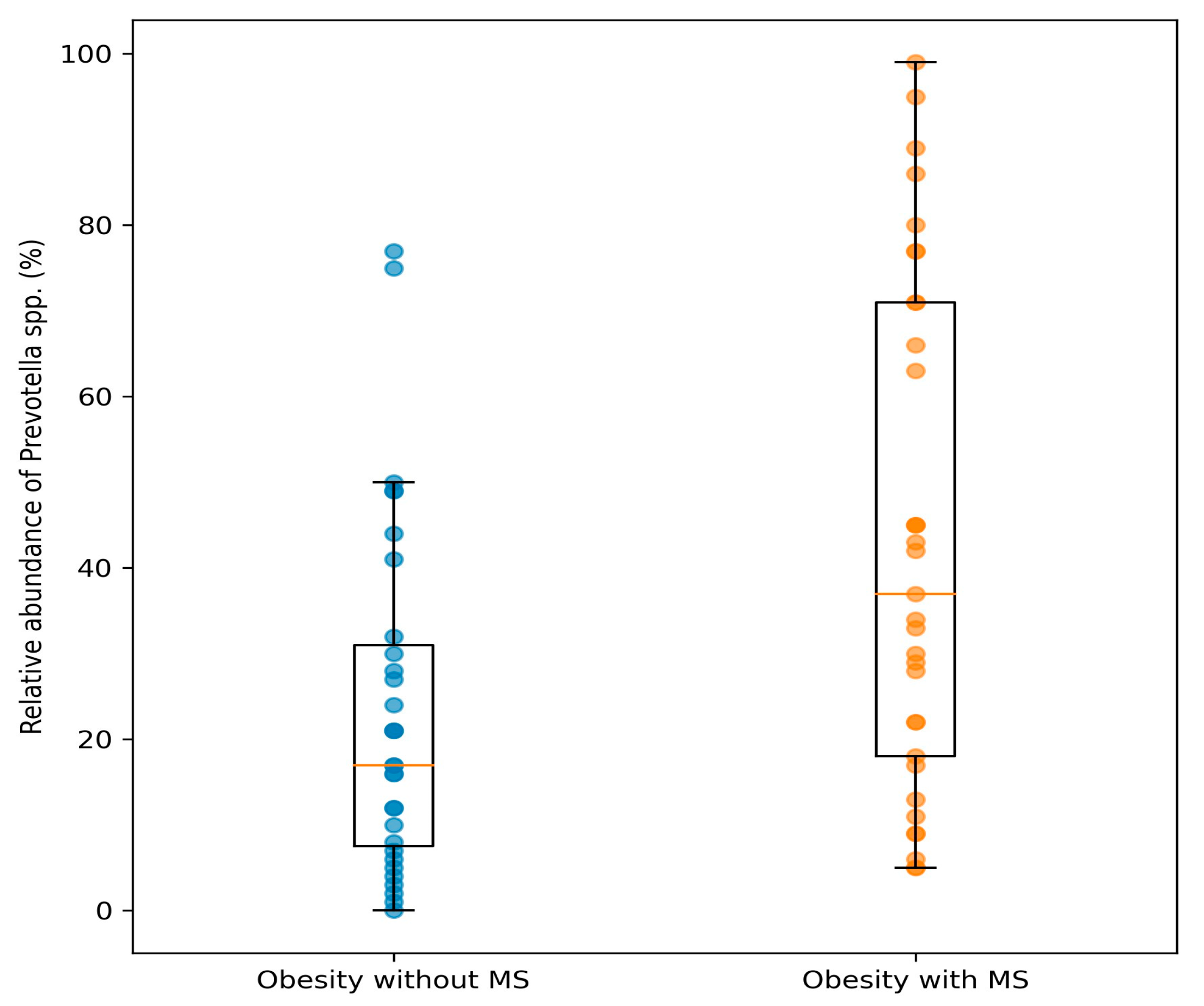

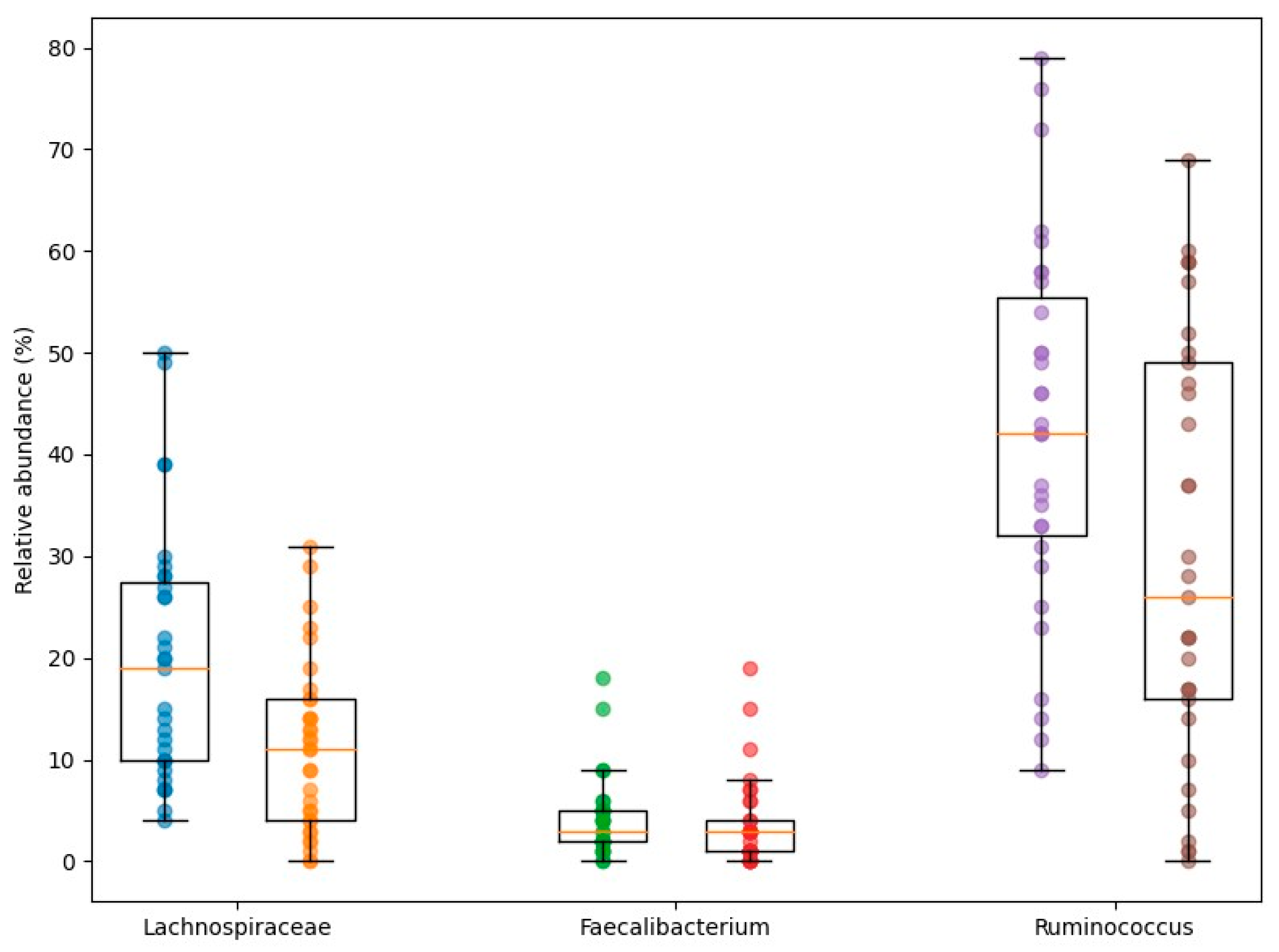

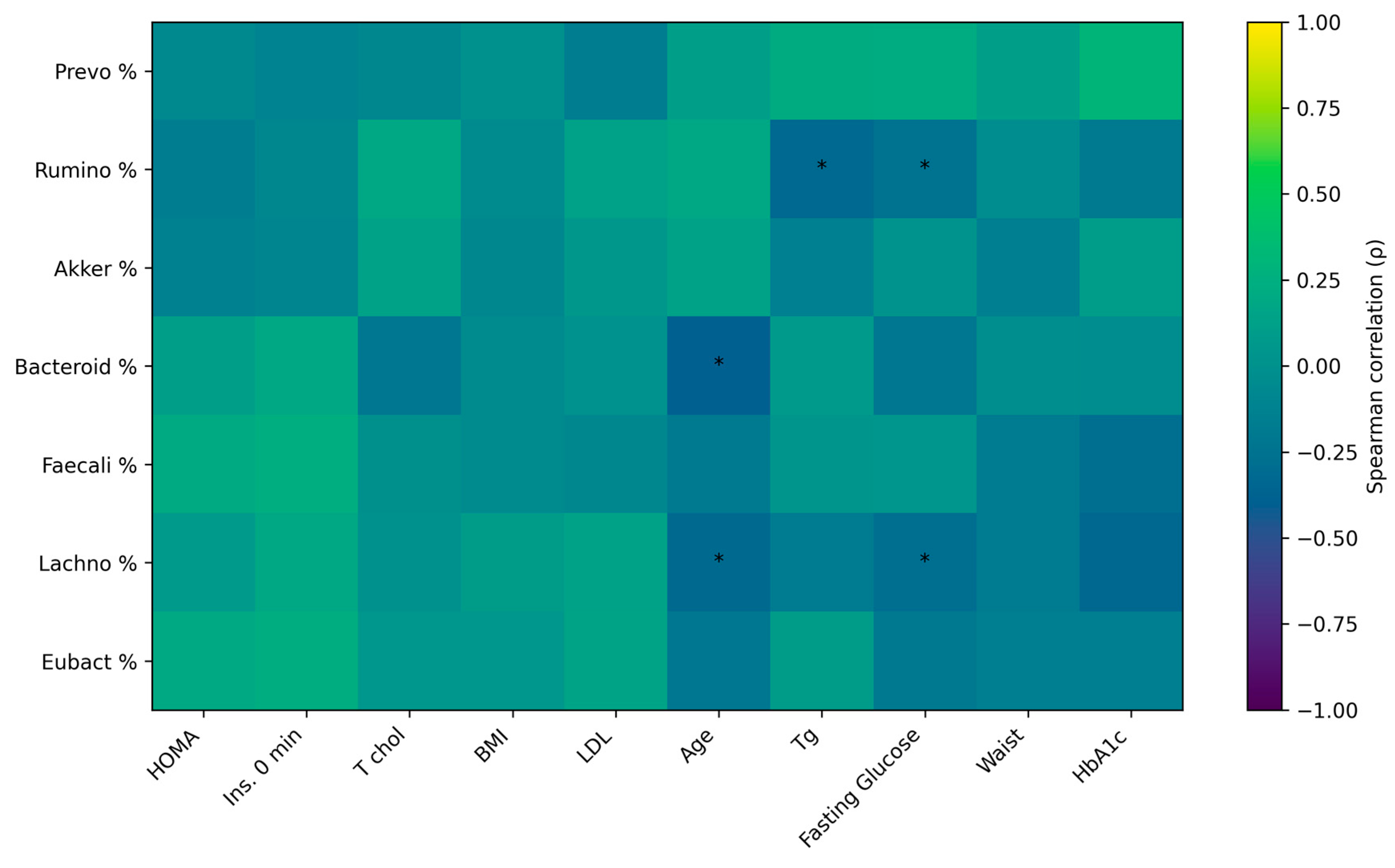

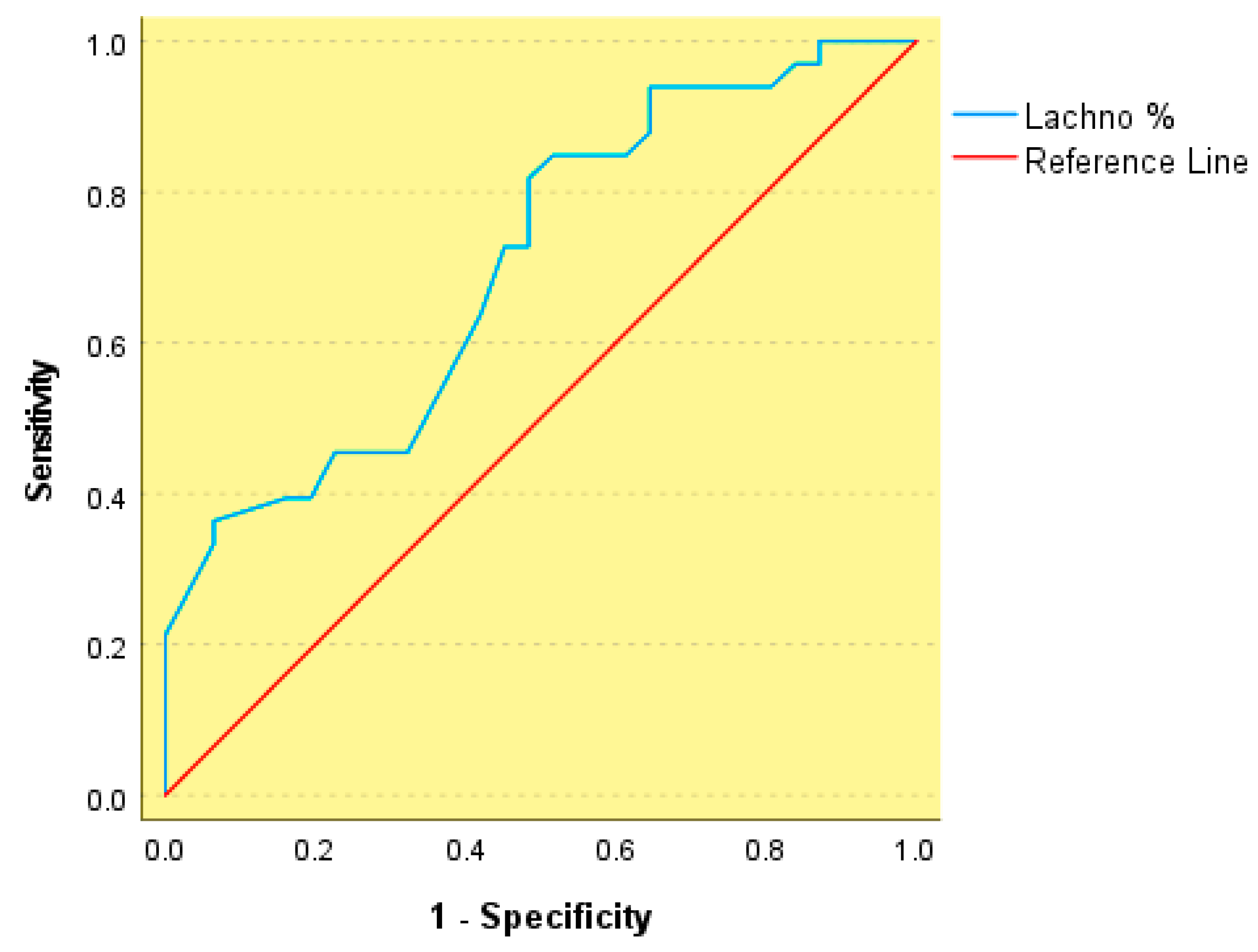

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loos, R.J.F.; Yeo, G.S.H. The Genetics of Obesity: From Discovery to Biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.D.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Kemnitz, J.W.; Klein, S.; Schoeller, D.A.; Speakman, J.R. Energy balance and its components: Implications for body weight regulation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 989–994, Erratum in Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, A.R.; Olefsky, J.M. Inflammatory Mechanisms Linking Obesity and Metabolic Disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut Microbiota in Human Metabolic Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Clément, K.; Nieuwdorp, M. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: A Future Therapeutic Option for Obesity/Diabetes? Curr. Diab. Rep. 2019, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovesy, L.; Masterson, D.; Rosado, E.L. Profile of the gut microbiota of adults with obesity: A systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, J.L.; Bäckhed, F. Diet–Microbiota Interactions as Moderators of Human Metabolism. Nature 2016, 535, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, M.; Li, Z.; You, H.; Rodrigues, R.; Jump, D.B.; Morgun, A.; Shulzhenko, N. Role of Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetes Pathophysiology. EBioMedicine 2020, 51, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.N.; Liu, X.T.; Liang, Z.H.; Wang, J.H. Gut Microbiota in Obesity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 3837–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, E.E.; Meex, R.C.R.; Venema, K.; Blaak, E.E. Gut Microbial Metabolites in Obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Microbiota–Gut–Brain Communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Amar, J.; Iglesias, M.A.; Poggi, M.; Knauf, C.; Bastelica, D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.M.; Chabo, C.; et al. Metabolic Endotoxemia Initiates Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D. Human Gut Microbiome: Hopes, Threats and Promises. Gut 2018, 67, 1716–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorucci, S.; Distrutti, E. Bile Acid-Activated Receptors, Intestinal Microbiota, and the Treatment of Metabolic Disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. Incretin Action in the Pancreas: Potential Promise, Possible Perils, and Pathological Pitfalls. Diabetes 2013, 62, 3316–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérard, P. Gut microbiota and obesity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H.K.; Gudmundsdottir, V.; Nielsen, H.B.; Hyotylainen, T.; Nielsen, T.; Jensen, B.A.H.; Forslund, K.; Hildebrand, F.; Prifti, E.; Falony, G.; et al. Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature 2016, 535, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, E.E.; Jocken, J.W.; Blaak, E.E. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Chatelier, E.; Nielsen, T.; Qin, J.; Prifti, E.; Hildebrand, F.; Falony, G.; Almeida, M.; Arumugam, M.; Batto, J.-M.; Kennedy, S.; et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 2013, 500, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, F.H.; Tremaroli, V.; Nookaew, I.; Bergström, G.; Behre, C.J.; Fagerberg, B.; Nielsen, J.; Bäckhed, F. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature 2013, 498, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Hong, J.; Xu, X.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, D.; Gu, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Gut microbiome and serum metabolome alterations in obesity and after weight-loss intervention. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; Shen, D.; et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, K.H.; Nielsen, T.; Pedersen, O. Mechanisms in endocrinology: Gut microbiota in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 172, R167–R177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Diversity, metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 294, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Besten, G.; van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.-J.; Bakker, B.M. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, E.S.; Preston, T.; Frost, G.; Morrison, D.J. Role of Gut Microbiota-Generated Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Metabolic and Cardiovascular Health. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2018, 7, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, H.; Pigneur, B.; Watterlot, L.; Lakhdari, O.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Gratadoux, J.-J.; Blugeon, S.; Bridonneau, C.; Furet, J.-P.; Corthier, G.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16731–16736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quévrain, E.; Maubert, M.A.; Michon, C.; Chain, F.; Marquant, R.; Tailhades, J.; Miquel, S.; Carlier, L.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Pigneur, B.; et al. Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2016, 65, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Siles, M.; Duncan, S.H.; Garcia-Gil, L.J.; Martinez-Medina, M. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: From microbiology to diagnostics and prognostics. ISME J. 2017, 11, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Gu, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, W.; Jia, L.; Chen, C.; Han, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, P.; et al. Alterations of the Gut Microbiome in Hypertension. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Tao, J.; Tian, G.; Wu, S.; Liu, W.; Cui, Q.; Geng, B.; et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome 2017, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Kitai, T.; Hazen, S.L. Gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluznick, J.L.; Protzko, R.J.; Gevorgyan, H.; Peterlin, Z.; Sipos, A.; Han, J.; Brunet, I.; Wan, L.-X.; Rey, F.; Wang, T.; et al. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4410–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, N.; Hori, D.; Flavahan, S.; Steppan, J.; Flavahan, N.A.; Berkowitz, D.E.; Pluznick, J.L. Microbial short chain fatty acid metabolites lower blood pressure via endothelial G protein-coupled receptor 41. Physiol. Genom. 2016, 48, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, F.Z.; Nelson, E.; Chu, P.-Y.; Horlock, D.; Fiedler, A.; Ziemann, M.; Tan, J.K.; Kuruppu, S.; Rajapakse, N.W.; El-Osta, A.; et al. High-fiber diet and acetate supplementation change the gut microbiota and prevent the development of hypertension and heart failure in hypertensive mice. Circulation 2017, 135, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, A.; Pasolli, E.; Masetti, G.; Ercolini, D.; Segata, N. Prevotella diversity, niches and interactions with the human host. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.M. The immune response to Prevotella bacteria in chronic inflammatory disease. Immunology 2017, 151, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, R.; Tremaroli, V.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Cani, P.D.; Bäckhed, F. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and dietary lipids aggravates WAT inflammation through TLR signaling. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlström, A.; Sayin, S.I.; Marschall, H.-U.; Bäckhed, F. Intestinal crosstalk between bile acids and microbiota and Its Impact on Host Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Group 1: Obesity (n = 50) | Group 2: MS (n = 50) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.74 ± 11.75 | 48.42 ± 12.66 | 0.148 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.05 ± 4.02 | 33.74 ± 3.09 | 0.629 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 96.77 ± 11.69 | 106.44 ± 11.51 | <0.001 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) | 0.85 [0.78–0.88] | 0.92 [0.84–0.99] | <0.001 |

| Waist-to-stature ratio (WSR) | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 0.66 ± 0.07 | 0.008 |

| Body fat (%) | 93.50 [85.00–98.25] | 106.00 [100.00–115.30] | <0.001 |

| Visceral fat rating (VFR) | 8.84 ± 2.88 | 11.21 ± 3.73 | 0.009 |

| Parameter | Group 1: Obesity (n = 50) | Group 2: MS (n = 50) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | 120 [110–130] | 140 [130–152.5] | 0.023 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80 [80–90] | 80 [80–90] | ns |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.3 [4.5–5.5] | 6.2 [4.4–7.3] | 0.042 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.21 ± 1.01 | 3.62 ± 0.86 | ns |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.32 ± 0.27 | 1.21 ± 0.28 | ns |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.46 ± 0.69 | 2.17 ± 0.95 | 0.007 |

| Hypertension (%) | 33.3 | 77.4 | 0.006 |

| Smoking (%) | 26.7 | 73.1 | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 31 | 74.2 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nedeva, I.; Assyov, Y.; Duleva, V.; Karamfilova, V.; Kamenov, Z.; Naydenov, J.; Handjieva-Darlenska, T.; Denchev, V.; Kolevski, A.; Pencheva, V.; et al. Distinct Gut Microbiome Profiles Underlying Cardiometabolic Risk Phenotypes in Individuals with Obesity. Nutrients 2026, 18, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020353

Nedeva I, Assyov Y, Duleva V, Karamfilova V, Kamenov Z, Naydenov J, Handjieva-Darlenska T, Denchev V, Kolevski A, Pencheva V, et al. Distinct Gut Microbiome Profiles Underlying Cardiometabolic Risk Phenotypes in Individuals with Obesity. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020353

Chicago/Turabian StyleNedeva, Iveta, Yavor Assyov, Veselka Duleva, Vera Karamfilova, Zdravko Kamenov, Julian Naydenov, Teodora Handjieva-Darlenska, Venelin Denchev, Alexander Kolevski, Victoria Pencheva, and et al. 2026. "Distinct Gut Microbiome Profiles Underlying Cardiometabolic Risk Phenotypes in Individuals with Obesity" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020353

APA StyleNedeva, I., Assyov, Y., Duleva, V., Karamfilova, V., Kamenov, Z., Naydenov, J., Handjieva-Darlenska, T., Denchev, V., Kolevski, A., Pencheva, V., & Vodenicharov, V. (2026). Distinct Gut Microbiome Profiles Underlying Cardiometabolic Risk Phenotypes in Individuals with Obesity. Nutrients, 18(2), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020353