Modulation of the Kynurenine Pathway in Obese Mexican Navy Women Following a Structured Weight Loss Program: A Pre–Post-Intervention Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Anthropometric Measurements

2.3. Laboratory Determinations

2.4. Weight Loss Program

2.5. Kynurenine Metabolites Determination

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

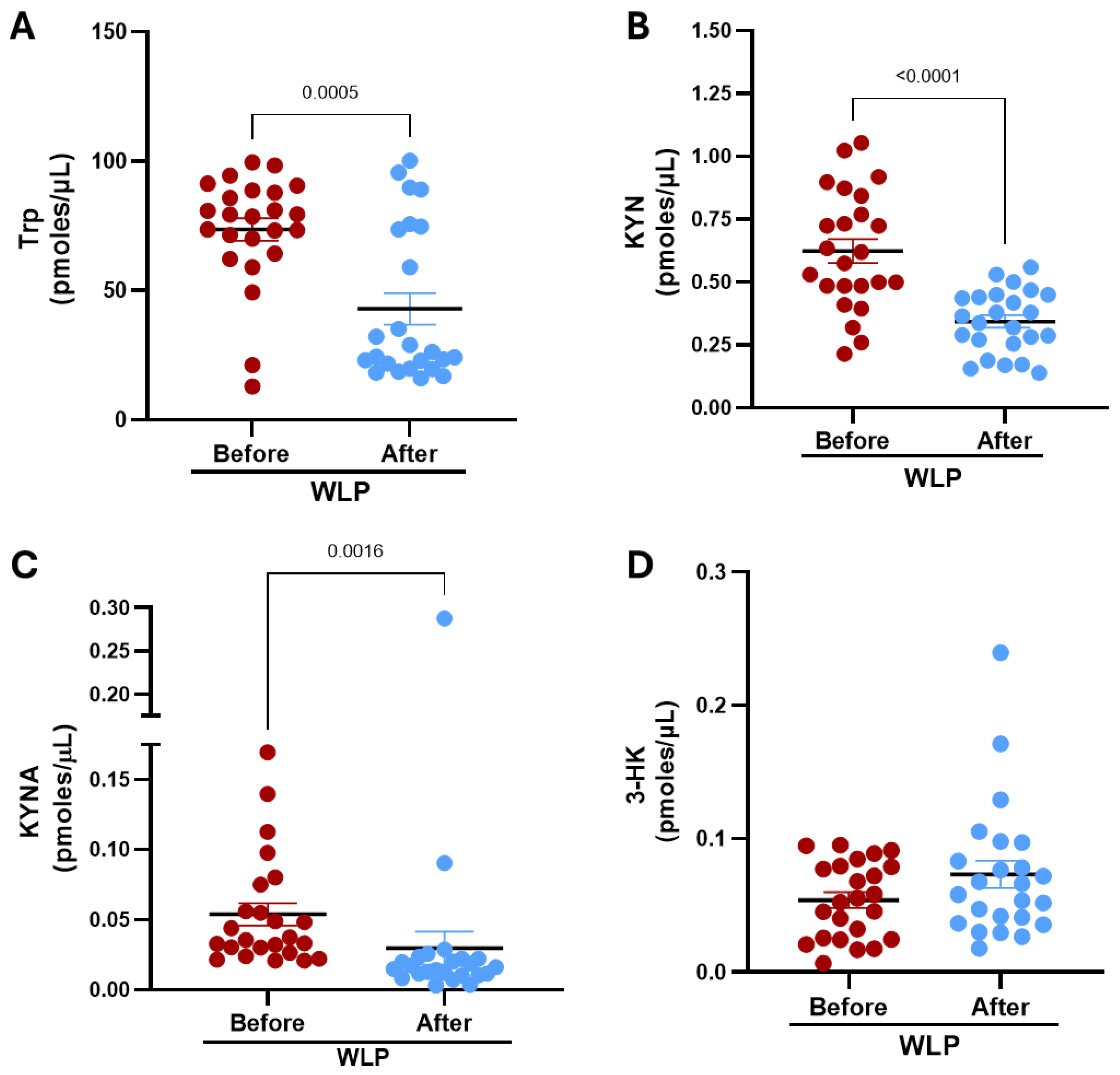

3.2. Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites in the Serum Before and After the WLP

3.3. Correlation Analysis of Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites with Clinical Parameters: Basal, Post-Intervention and as Relative Change

3.4. Correlation Analysis Between Relative Changes in Anxiety, Depression and KP Metabolites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3-HK | 3-hydroxykynurenine |

| AA | Anthranilic acid |

| AhR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase, |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| cLGI | Chronic low-grade inflammation |

| CRP | Serum C-reactive protein |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| GPR35 | G-protein-coupled receptor 35 |

| HCl4 | Perchloric acid |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| IDO1 | Nicotinamide adenine indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 |

| IDO2 | Nicotinamide adenine indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2 |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| ISAK | International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry |

| KATs | Kynurenine aminotransferases |

| KMO | Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase |

| KP | Kynurenine pathway |

| KYN | Kynurenine |

| KYNA | Kynurenic acid |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| METs | Metabolic Equivalent of Task units |

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| PA | Picolinic acid |

| QUIN | Quinolinic acid |

| SECTEI | Secretaría de Educación, Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TDO | Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| Trp | Tryptophan |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WLP | Weight loss program |

| XA | Xanthurenic acid |

References

- World Health Organization Obesity. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/obesity#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Barquera, S.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Trejo-Valdivia, B.; Shamah, T.; Campos-Nonato, I.; Rivera-Dommarco, J. Obesity in Mexico, Prevalence and Trends in Adults. Salud Publica Mex. 2018, 62, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Nonato, I.; Galván-Valencia, O.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Oviedo-Solís, C.; Barquera, S. Prevalence of Obesity and Associated Risk Factors in Mexican Adults: Results of the Ensanut 2022. Salud Publica Mex. 2023, 65, s238–s247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Movassat, J.; Portha, B. Emerging Role for Kynurenines in Metabolic Pathologies. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2019, 22, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon-Biet, S.M.; Cogger, V.C.; Pulpitel, T.; Wahl, D.; Clark, X.; Bagley, E.E.; Gregoriou, G.C.; Senior, A.M.; Wang, Q.P.; Brandon, A.E.; et al. Branched Chain Amino Acids Impact Health and Lifespan Indirectly via Amino Acid Balance and Appetite Control. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Kema, I.; Bosker, F.; Haavik, J.; Korf, J. Tryptophan as an Evolutionarily Conserved Signal to Brain Serotonin: Molecular Evidence and Psychiatric Implications. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 10, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, A.A.B. Kynurenine Pathway of Tryptophan Metabolism: Regulatory and Functional Aspects. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2017, 10, 1178646917691938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddick, J.P.; Evans, A.K.; Nutt, D.J.; Lightman, S.L.; Rook, G.A.W.; Lowry, C.A. Tryptophan Metabolism in the Central Nervous System: Medical Implications. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2006, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palego, L.; Betti, L.; Rossi, A.; Giannaccini, G. Tryptophan Biochemistry: Structural, Nutritional, Metabolic, and Medical Aspects in Humans. J. Amino Acids 2016, 2016, 8952520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; May, C.L.; Dastugue, A.; Ayer, A.; Blanchard, C.; Martin, J.C.; de Barros, J.P.P.; Delaby, P.; Bourgot, C.L.; Ledoux, S.; et al. The Tryptophan/Kynurenine Pathway: A Novel Cross-Talk between Nutritional Obesity, Bariatric Surgery and Taste of Fat. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.M.; Charych, E.; Lee, A.W.; Möller, T. Kynurenines in CNS Disease: Regulation by Inflammatory Cytokines. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, D.; Song, P.; Zou, M.H. Tryptophan-Kynurenine Pathway Is Dysregulated in Inflammation and Immune Activation. Front. Biosci. 2015, 20, 1116–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolowczuk, I.; Hennart, B.; Leloire, A.; Bessede, A.; Soichot, M.; Taront, S.; Caiazzo, R.; Raverdy, V.; Pigeyre, M.; Guillemin, G.J.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolism Activation by Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase in Adipose Tissue of Obese Women: An Attempt to Maintain Immune Homeostasis and Vascular Tone. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2012, 303, R135–R143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, L.Z.; Ferreira, D.M.S.; Dadvar, S.; Cervenka, I.; Ketscher, L.; Izadi, M.; Zhengye, L.; Furrer, R.; Handschin, C.; Venckunas, T.; et al. Skeletal Muscle PGC-1α1 Reroutes Kynurenine Metabolism to Increase Energy Efficiency and Fatigue-Resistance. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agudelo, L.Z.; Ferreira, D.M.S.; Cervenka, I.; Bryzgalova, G.; Dadvar, S.; Jannig, P.R.; Pettersson-Klein, A.T.; Lakshmikanth, T.; Sustarsic, E.G.; Porsmyr-Palmertz, M.; et al. Kynurenic Acid and Gpr35 Regulate Adipose Tissue Energy Homeostasis and Inflammation. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 378–392.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandacher, G.; Winkler, C.; Aigner, F.; Schwelberger, H.; Schroecksnadel, K.; Margreiter, R.; Fuchs, D.; Weiss, H.G. Bariatric Surgery Cannot Prevent Tryptophan Depletion Due to Chronic Immune Activation in Morbidly Obese Patients. Obes. Surg. 2006, 16, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervenka, I.; Agudelo, L.Z.; Ruas, J.L. Kynurenines: Tryptophan’s Metabolites in Exercise, Inflammation, and Mental Health. Science 2017, 357, eaaf9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussotto, S.; Delgado, I.; Anesi, A.; Dexpert, S.; Aubert, A.; Beau, C.; Forestier, D.; Ledaguenel, P.; Magne, E.; Mattivi, F.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolic Pathways Are Altered in Obesity and Are Associated With Systemic Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favennec, M.; Hennart, B.; Caiazzo, R.; Leloire, A.; Yengo, L.; Verbanck, M.; Arredouani, A.; Marre, M.; Pigeyre, M.; Bessede, A.; et al. The Kynurenine Pathway Is Activated in Human Obesity and Shifted toward Kynurenine Monooxygenase Activation. Obesity 2015, 23, 2066–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Song, J.; Gao, J.; Cheng, J.; Xie, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.H.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Adipocyte-Derived Kynurenine Promotes Obesity and Insulin Resistance by Activating the AhR/STAT3/IL-6 Signaling. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, M.V.d.S.; Lopes, K.G.; Qin, X.; Borges, J.P. Exercise-Induced Adaptations in the Kynurenine Pathway: Implications for Health and Disease Management. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1535152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saran, T.; Turska, M.; Kocki, T.; Zawadka, M.; Zieliński, G.; Turski, W.A.; Gawda, P. Effect of 4-Week Physical Exercises on Tryptophan, Kynurenine and Kynurenic Acid Content in Human Sweat. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubacka, J.; Staniszewska, M.; Sadok, I.; Sypniewska, G.; Stefanska, A. The Kynurenine Pathway in Obese Middle-Aged Women with Normoglycemia and Type 2 Diabetes. Metabolites 2022, 12, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, M.A.; da Silva, I.; Ramires, V.; Reichert, F.; Martins, R.; Ferreira, R.; Tomasi, E. Metabolic Equivalent of Task (METs) Thresholds as an Indicator of Physical Activity Intensity. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social Prescripción de Ejercicios Con Plan Terapéutico En El Adulto. Evidencias y Recomendaciones Catálogo Maestro de Guías de Práctica Clínica: IMSS-626-13. 2013. Available online: https://www.imss.gob.mx/sites/all/statics/guiasclinicas/626GRR.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Wu, H.Q.; Ungerstedt, U.; Schwarcz, R. Regulation of Kynurenic Acid Synthesis Studied by Microdialysis in the Dorsal Hippocampus of Unanesthetized Rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992, 213, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.M.; Bouchard, C.; Church, T.; Slentz, C.; Kraus, W.E.; Redman, L.M.; Martin, C.K.; Silva, A.M.; Vossen, M.; Westerterp, K.; et al. Why Do Individuals Not Lose More Weight from an Exercise Intervention at a Defined Dose? An Energy Balance Analysis. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorogood, A.; Mottillo, S.; Shimony, A.; Filion, K.B.; Joseph, L.; Genest, J.; Pilote, L.; Poirier, P.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Eisenberg, M.J. Isolated Aerobic Exercise and Weight Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Med. 2011, 124, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villareal, D.T.; Chode, S.; Parimi, N.; Sinacore, D.R.; Hilton, T.; Armamento-Villareal, R.; Napoli, N.; Qualls, C.; Shah, K. Weight Loss, Exercise, or Both and Physical Function in Obese Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1218–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosy-Westphal, A.; Kossel, E.; Goele, K.; Later, W.; Hitze, B.; Settler, U.; Heller, M.; Glüer, C.C.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Müller, M.J. Contribution of Individual Organ Mass Loss to Weight Loss-Associated Decline in Resting Energy Expenditure. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.P.; Jordan, R.C.; Frese, E.M.; Albert, S.G.; Villareal, D.T. Effects of Weight Loss on Lean Mass, Strength, Bone, and Aerobic Capacity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, J.J.; Amati, F.; Toledo, F.G.S.; Stefanovic-Racic, M.; Rossi, A.; Coen, P.; Goodpaster, B.H. Effects of Weight Loss and Exercise on Insulin Resistance, and Intramyocellular Triacylglycerol, Diacylglycerol and Ceramide. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, E.A.; Hargreaves, M. Exercise, GLUT4, and Skeletal Muscle Glucose Uptake. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 993–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikłosz, A.; Konstantynowicz, K.; Stepek, T.; Chabowski, A. The Role of Protein AS160/TBC1D4 in the Transport of Glucose into Skeletal Muscles. Postępy Hig. I Med. Doświadczalnej 2011, 65, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.L.; Distelmaier, K.; Lanza, I.R.; Irving, B.A.; Robinson, M.M.; Konopka, A.R.; Shulman, G.I.; Nair, K.S. Mechanism by Which Caloric Restriction Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Sedentary Obese Adults. Diabetes 2016, 65, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasteyger, C.; Larsen, T.M.; Vercruysse, F.; Astrup, A. Effect of a Dietary-Induced Weight Loss on Liver Enzymes in Obese Subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Ye, J.; Shao, C.; Lin, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhong, B. Metabolic Benefits of Changing Sedentary Lifestyles in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 13, 20420188221122426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joisten, N.; Kummerhoff, F.; Koliamitra, C.; Schenk, A.; Walzik, D.; Hardt, L.; Knoop, A.; Thevis, M.; Kiesl, D.; Metcalfe, A.J.; et al. Exercise and the Kynurenine Pathway: Current State of Knowledge and Results from a Randomized Cross-over Study Comparing Acute Effects of Endurance and Resistance Training. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 26, 24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sadok, I.; Jędruchniewicz, K. Dietary Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites-Source, Fate, and Chromatographic Determinations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, K.T.D.; Penney, N.; Whiley, L.; Ashrafian, H.; Lewis, M.R.; Purkayastha, S.; Darzi, A.; Holmes, E. The Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Serum Tryptophan-Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.; Berger, K.; Fuchs, D. Effects of a Caloric Restriction Weight Loss Diet on Tryptophan Metabolism and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Overweight Adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.; Gostner, J.M.; Fuchs, D. Mood, Food, and Cognition: Role of Tryptophan and Serotonin. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2016, 19, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, M.; Spriet, L.L. Skeletal Muscle Energy Metabolism during Exercise. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, G.J.; Rhee, C.M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Joshi, S. The Effects of High-Protein Diets on Kidney Health and Longevity. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Esquivel, D.; Ramírez-Ortega, D.; Pineda, B.; Castro, N.; Ríos, C.; Pérez de la Cruz, V. Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites and Enzymes Involved in Redox Reactions. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Choue, R. Metabolic Responses to High Protein Diet in Korean Elite Bodybuilders with High-Intensity Resistance Exercise. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2011, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.H.E.; Fadnes, D.J.; Røst, T.H.; Pedersen, E.R.; Andersen, J.R.; Våge, V.; Ulvik, A.; Midttun, Ø.; Ueland, P.M.; Nygård, O.K.; et al. Inflammatory Markers, the Tryptophan-Kynurenine Pathway, and Vitamin B Status after Bariatric Surgery. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Pires, A.S.; Guller, A.; Chaganti, J.; Tun, N.; Lockart, I.; Montagnese, S.; Brew, B.; Guillemin, G.J.; et al. Activation of the Kynurenine Pathway Identified in Individuals with Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8, e0559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clària, J.; Moreau, R.; Fenaille, F.; Amorós, A.; Junot, C.; Gronbaek, H.; Coenraad, M.J.; Pruvost, A.; Ghettas, A.; Chu-Van, E.; et al. Orchestration of Tryptophan-Kynurenine Pathway, Acute Decompensation, and Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1686–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, O.P.; Lehti, M.; Kyröläinen, H.; Kainulainen, H. Heme Oxygenase-1 and Blood Bilirubin Are Gradually Activated by Oral D-Glyceric Acid. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítek, L.; Schwertner, H.A. The Heme Catabolic Pathway and Its Protective Effects on Oxidative Stress-Mediated Diseases. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2007, 43, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Deng, S.; Xiong, L. Role of Kynurenine and Its Derivatives in Liver Diseases: Recent Advances and Future Clinical Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Mora, P.; Pérez-De la Cruz, V.; Estrada-Cortés, B.; Toussaint-González, P.; Martínez-Cortéz, J.A.; Rodríguez-Barragán, M.; Quinzaños-Fresnedo, J.; Rangel-Caballero, F.; Gamboa-Coria, G.; Sánchez-Vázquez, I.; et al. Serum Kynurenines Correlate With Depressive Symptoms and Disability in Poststroke Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2020, 34, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, L.Z.; Femenía, T.; Orhan, F.; Porsmyr-Palmertz, M.; Goiny, M.; Martinez-Redondo, V.; Correia, J.C.; Izadi, M.; Bhat, M.; Schuppe-Koistinen, I.; et al. Skeletal Muscle PGC-1α1 Modulates Kynurenine Metabolism and Mediates Resilience to Stress-Induced Depression. Cell 2014, 159, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, H.M.; Stevenson, R.J.; Tan, L.S.Y.; Ehrenfeld, L.; Byeon, S.; Attuquayefio, T.; Gupta, D.; Lim, C.K. Kynurenic Acid as a Biochemical Factor Underlying the Association between Western-Style Diet and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 945538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeusen, R.; De Meirleir, K. Exercise and Brain Neurotransmission. Sports Med. 1995, 20, 160–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernstrom, J.D.; Fernstrom, M.H. Exercise, Serum Free Tryptophan, and Central Fatigue. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 553S–559S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asante, D.M.; Vyavahare, S.; Shukla, M.; McGee-Lawrence, M.E.; Isales, C.M.; Fulzele, S. Exercise-Driven Changes in Tryptophan Metabolism Leading to Healthy Aging. Biochimie 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Before | After | p-Value | Clinical Reference Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body composition analysis | ||||

| Weight (Kg) | 89.59 (2.13) | 80.4 (2.01) | <0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.04 (0.7) | 31.39 (0.68) | <0.001 | 18.5–24.9 normal |

| 25–29.9 overweight | ||||

| 30–34.9 obesity I | ||||

| 35–39.9 obesity II | ||||

| 40–49.9 obesity III | ||||

| Body fat (%) | 45.52 (0.85) | 40.76 (1.03) | <0.001 | Female < 35 |

| Body fat mass (Kg) | 41.13 (1.56) | 32.67 (1.47) | <0.001 | - |

| Free body fat mass % | 54.48 (0.85) | 59.24 (1.03) | <0.001 | - |

| Free body fat mass (Kg) | 47.54 (0.78) | 46.96 (0.8) | 0.018 | - |

| Muscle mass (Kg) | 24.68 (0.71) | 24.24 (0.73) | 0.009 | - |

| Serum Biochemistry | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 94.87 (2.99) | 94.09 (2.09) | 0.83 | 65–95 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 44.38 (1.93) | 43.67 (1.33) | 0.974 | 40–60 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 127.54 (8.72) | 123.49 (5.9) | 0.855 | <129 |

| VLDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 23.92 (1.54) | 21.99 (1.68) | 0.214 | 2–30 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 195.96 (10.01) | 188.71 (7.45) | 0.372 | <200 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 122.17 (8.27) | 109.83 (8.41) | 0.121 | <150 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0.68 (0.15) | 0.37 (0.1) | <0.001 | 0–0.8 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 5.44 (0.2) | 5.37 (0.19) | 0.647 | 2.5–5.6 |

| Insulin (Uu/mL) | 11.18 (0.98) | 8.34 (1.16) | 0.02 | 2–20 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 10.77 (0.59) | 13.67 (0.89) | <0.001 | 7–20 |

| Cortisol (µg/dL) | 6.85 (0.73) | 9.08 (0.61) | 0.006 | 8.7–22.4 |

| Liver panel | ||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.76 (0.05) | 0.73 (0.05) | 0.569 | 0.2–1 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.239 | 0–0.2 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.04) | 0.65 (0.05) | 0.362 | 0–0.85 |

| AST (UI/L) | 24.96 (2.22) | 21.04 (0.97) | 0.116 | 10–42 |

| ALT (UI/L) | 33.14 (5.33) | 22.18 (1.35) | 0.06 | 10–40 |

| GGT (UI/L) | 23.43 (2.38) | 14.83 (1.1) | <0.001 | 8.37 |

| ALP (UI/L) | 61.63 (3.02) | 54.49 (2.11) | 0.005 | 32.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Chapul, L.; Ramírez-Ortega, D.; Samudio-Cruz, M.A.; Cabrera-Ruiz, E.; Luna-Angulo, A.; Pérez de la Cruz, G.; Valencia-León, J.F.; Carillo-Mora, P.; Landa-Solís, C.; Rangel-López, E.; et al. Modulation of the Kynurenine Pathway in Obese Mexican Navy Women Following a Structured Weight Loss Program: A Pre–Post-Intervention Study. Nutrients 2026, 18, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020211

Sánchez-Chapul L, Ramírez-Ortega D, Samudio-Cruz MA, Cabrera-Ruiz E, Luna-Angulo A, Pérez de la Cruz G, Valencia-León JF, Carillo-Mora P, Landa-Solís C, Rangel-López E, et al. Modulation of the Kynurenine Pathway in Obese Mexican Navy Women Following a Structured Weight Loss Program: A Pre–Post-Intervention Study. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020211

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Chapul, Laura, Daniela Ramírez-Ortega, María Alejandra Samudio-Cruz, Elizabeth Cabrera-Ruiz, Alexandra Luna-Angulo, Gonzalo Pérez de la Cruz, Jesús F. Valencia-León, Paul Carillo-Mora, Carlos Landa-Solís, Edgar Rangel-López, and et al. 2026. "Modulation of the Kynurenine Pathway in Obese Mexican Navy Women Following a Structured Weight Loss Program: A Pre–Post-Intervention Study" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020211

APA StyleSánchez-Chapul, L., Ramírez-Ortega, D., Samudio-Cruz, M. A., Cabrera-Ruiz, E., Luna-Angulo, A., Pérez de la Cruz, G., Valencia-León, J. F., Carillo-Mora, P., Landa-Solís, C., Rangel-López, E., Morraz-Varela, A., Romero-Sánchez, M. T., & Pérez de la Cruz, V. (2026). Modulation of the Kynurenine Pathway in Obese Mexican Navy Women Following a Structured Weight Loss Program: A Pre–Post-Intervention Study. Nutrients, 18(2), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020211