Effects of Phytochemicals on Atherosclerosis: Based on the Gut–Liver Axis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Composition and Function of the Gut Microenvironment in Healthy Individuals and Atherosclerosis Patients

3. The Role of the Gut–Liver Axis in Atherosclerosis

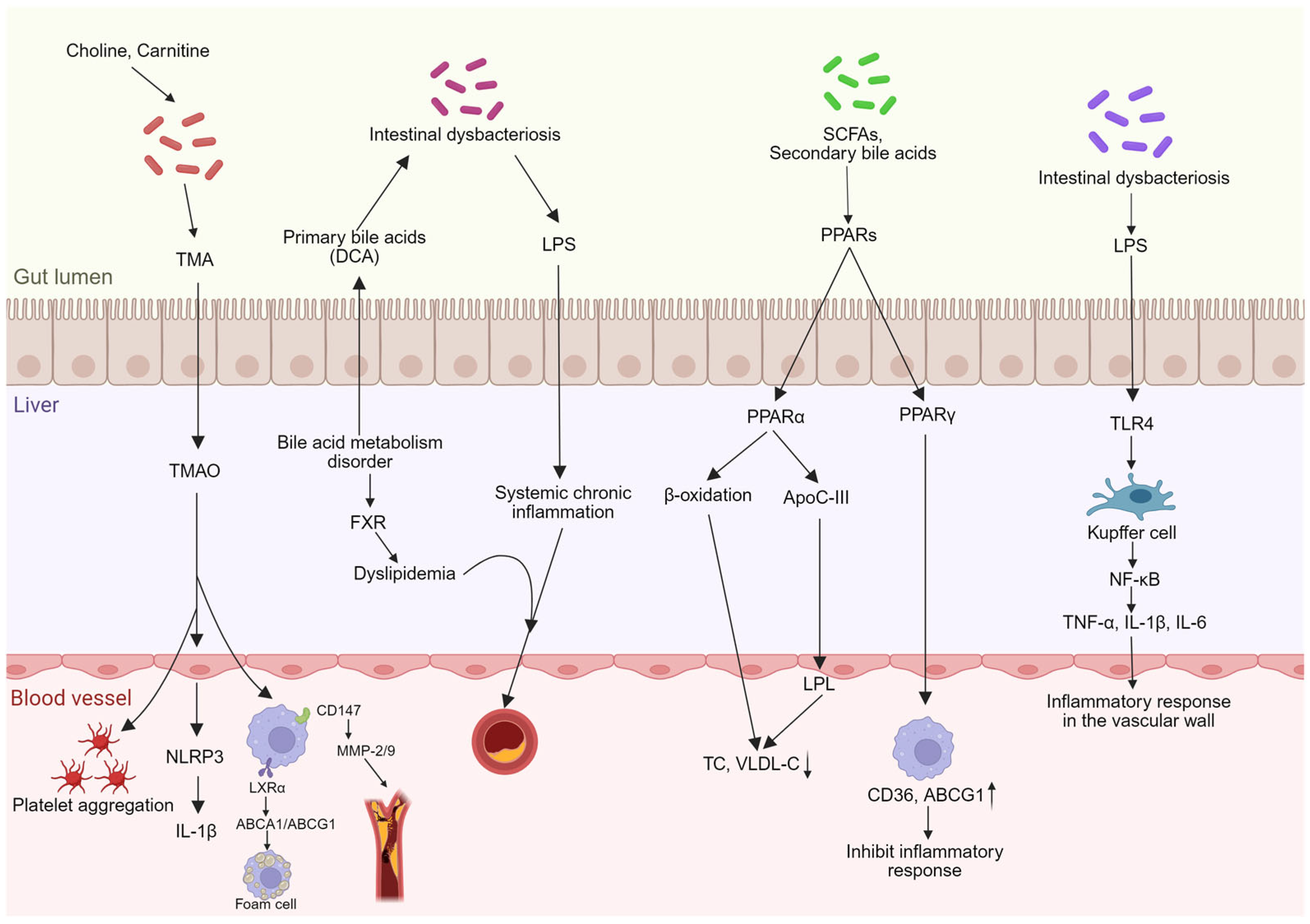

3.1. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Barrier Impairment

3.2. Regulation of Bile Acid Metabolism

3.3. Lipid Metabolism

3.4. Inflammatory Response

4. Mechanisms of Phytochemicals Affecting the Gut–Liver Axis

4.1. Modulating Gut Microbiota Structure

4.2. Repairing and Enhancing the Intestinal Barrier

4.3. Regulation of Bile Acid Metabolism

4.4. Modulating Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Responses

5. Phytochemicals Influence Atherosclerosis Through the Gut–Liver Axis

5.1. Polyphenolic Compounds

5.2. Carotenoids

5.3. Panax Ginsenosides

5.4. Phytoestrogens

5.5. Phytosterols

5.6. Other Phytochemicals

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS | Atherosclerosis |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| FXR | Farnesoid X receptor |

| TGR5 | Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 |

| PPARs | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors |

| IL | Interleukin (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6) |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| LDLR | Low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| VLDL | Very low-density lipoprotein |

| ox-LDL | Oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| CYP7A1 | Cholesterol 7-alpha hydroxylase |

| BSH | Bile salt hydrolase |

| ABCA1/ABCG1 | ATP-binding cassette transporter A1/G1 |

| LXRα | Liver X receptor alpha |

| HMG-CoA | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| sIgA | Secretory immunoglobulin A |

| AMPs | Antimicrobial peptides |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| GPR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| RCT | Reverse cholesterol transport |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GPX | Glutathione peroxidase |

References

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Shapses, S.A. Guidance on Energy and Macronutrients across the Life Span. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B. Plant-based foods and prevention of cardiovascular disease: An overview. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 544S–551S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Liu, J.; He, L.; Jiang, J.; Gong, T.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Tang, N.; Chen, Z. Integrative analysis of the transcriptome and metabolome reveals the peel coloration mechanism of Zanthoxylum armatum. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R. Atherosclerosis—An inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks 2023 Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2023. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 2167–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Watanabe, T. Atherosclerosis: Known and unknown. Pathol. Int. 2022, 72, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, M.; Weeks, T.L.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, M. Human digestion—A processing perspective. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 2275–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eraghieh Farahani, H.; Pourhajibagher, M.; Asgharzadeh, S.; Bahador, A. Postbiotics: Novel Modulators of Gut Health, Metabolism, and Their Mechanisms of Action. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins, 2025; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, P.; Saha, K.; Nighot, P. Intestinal Epithelial Tight Junction Barrier Regulation by Novel Pathways. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, 31, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massier, L.; Blüher, M.; Kovacs, P.; Chakaroun, R.M. Impaired Intestinal Barrier and Tissue Bacteria: Pathomechanisms for Metabolic Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 616506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Mande, S.S. Host-microbiome interactions: Gut-Liver axis and its connection with other organs. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.L.; Schnabl, B. The gut-liver axis and gut microbiota in health and liver disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; van Esch, B.C.A.M.; Henricks, P.A.J.; Folkerts, G.; Garssen, J. The Anti-inflammatory Effects of Short Chain Fatty Acids on Lipopolysaccharide- or Tumor Necrosis Factor α-Stimulated Endothelial Cells via Activation of GPR41/43 and Inhibition of HDACs. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, F.; Mubbashir, A.; Khan, M.S.; Shaikh, Z.; Memon, A.; Alvares, J.; Azhar, A.; Jain, H.; Ahmed, R.; Kanagala, S.G. Trimethylamine N-oxide in cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology and the potential role of statins. Life Sci. 2025, 361, 123304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Buffa, J.A.; Gupta, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Mehrabian, M.; et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 2016, 165, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, R.; Thirumurugan, D.; Vinayagam, S.; Kim, D.J.; Suk, K.T.; Iyer, M.; Yadav, M.K.; HariKrishnaReddy, D.; Parkash, J.; Wander, A.; et al. A critical review of microbiome-derived metabolic functions and translational research in liver diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1488874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, M.Z.; Virgolici, B.; Doicin, I.C.; Vîrgolici, H.; Stanescu-Spinu, I.I. Navigating the Effects of Anti-Atherosclerotic Supplements and Acknowledging Associated Bleeding Risks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.Q.; Song, S.Y.; Xu, Q.; Zang, T.T.; Wang, L.S.; Shen, L.; Ge, J.B. Dietary fiber pectin supplement attenuates atherosclerosis through promoting Akkermansia-related acetic acid metabolism. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2025, 148, 157373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiertsema, S.P.; van Bergenhenegouwen, J.; Garssen, J.; Knippels, L.M.J. The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becattini, S.; Sorbara, M.T.; Kim, S.G.; Littmann, E.L.; Dong, Q.; Walsh, G.; Wright, R.; Amoretti, L.; Fontana, E.; Hohl, T.M.; et al. Rapid transcriptional and metabolic adaptation of intestinal microbes to host immune activation. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 378–393.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, C.; Huang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guo, L.; Xia, T.; Huang, F.; Yan, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, B. Synergistic interactions between gut microbiota and short chain fatty acids: Pioneering therapeutic frontiers in chronic disease management. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 199, 107231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age. Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, C.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Rizzatti, G.; Gibiino, G.; Cennamo, V.; Gasbarrini, A. Actinobacteria: A relevant minority for the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Dig. Liver Dis. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2018, 50, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Pei, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Lu, W. Bridging dietary polysaccharides and gut microbiome: How to achieve precision modulation for gut health promotion. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 292, 128046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandrescu, L.; Suceveanu, A.P.; Stanigut, A.M.; Tofolean, D.E.; Axelerad, A.D.; Iordache, I.E.; Herlo, A.; Nelson Twakor, A.; Nicoara, A.D.; Tocia, C.; et al. Intestinal Insights: The Gut Microbiome’s Role in Atherosclerotic Disease: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Ge, J. Recent advances in the gut microbiome and microbial metabolites alterations of coronary artery disease. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrangelo, A.; Robles-Vera, I.; Mañanes, D.; Galán, M.; Femenía-Muiña, M.; Redondo-Urzainqui, A.; Barrero-Rodríguez, R.; Papaioannou, E.; Amores-Iniesta, J.; Devesa, A.; et al. Imidazole propionate is a driver and therapeutic target in atherosclerosis. Nature 2025, 645, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lyu, J.; Zhao, R.; Liu, G.; Wang, S. Gut macrobiotic and its metabolic pathways modulate cardiovascular disease. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1272479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, P.; Qu, Y.; Zhong, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, W.; Yang, W.; Xu, H.; Zhao, X.; et al. The gut microbiota-bile acid-TGR5 axis orchestrates platelet activation and atherothrombosis. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 4, 584–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Q.; Yin, Y. Butyrate in Energy Metabolism: There Is Still More to Learn. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 2021, 32, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usami, M.; Miyoshi, M.; Kanbara, Y.; Aoyama, M.; Sakaki, H.; Shuno, K.; Hirata, K.; Takahashi, M.; Ueno, K.; Hamada, Y.; et al. Analysis of fecal microbiota, organic acids and plasma lipids in hepatic cancer patients with or without liver cirrhosis. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Gao, K.; Peng, K.; Bi, S.; Cui, X.; Liu, Y. A Review of Nutritional Regulation of Intestinal Butyrate Synthesis: Interactions Between Dietary Polysaccharides and Proteins. Foods 2025, 14, 3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eladl, O. Biophysical and transcriptomic characterization of LL-37-derived antimicrobial peptide targeting multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli and ESKAPE pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.; Baranova, D.; Mantis, N.J. The prospect of orally administered monoclonal secretory IgA (SIgA) antibodies to prevent enteric bacterial infections. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1964317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, X.; Luo, H.; Lei, R.; Lou, X.; Bian, J.; Guo, J.; Luo, H.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, Q.; Gong, W. Association between Intestinal Microecological Changes and Atherothrombosis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, J.C.; Cen, F.L.; Zhang, X.; Nong, X.H.; Zhou, X.M.; Li, X.B.; Yu, Z.X.; Chen, G.Y. Nor-halimane and spiro-labdane diterpenoids with anti-inflammatory activity from Leucas ciliata Benth. Phytochemistry 2026, 241, 114681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tian, J.; Lei, M.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, Y. Association between dietary fiber intake and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults: A cross-sectional study of 14,947 population based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiyajai, P.; Trangcasanchai, P.; Thapprathum, P.; Soonkum, T.; Sridonpai, P.; Kitdumrongthum, S.; Judprasong, K.; Kriengsinyos, W.; Prachansuwan, A. Faecal short-chain fatty acids and nutritional factors in Thai adults with hypercholesterolaemia compared to normocholesterolemic subjects. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 76, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; van Esch, B.C.; Henricks, P.A.; Garssen, J.; Folkerts, G. IL-33 Is Involved in the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Butyrate and Propionate on TNFα-Activated Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, C.A.; Naelitz, B.D.; Wang, Z.; Jia, X.; Li, J.; Stampfer, M.J.; Klein, E.A.; Hazen, S.L.; Sharifi, N. Gut Microbiome-Dependent Metabolic Pathways and Risk of Lethal Prostate Cancer: Prospective Analysis of a PLCO Cancer Screening Trial Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2022, 31, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonna, E.; Abate, F.; Schiano, E.; Paparella, F.; Ferrara, F.; Vanoli, E.; Difruscolo, R.; Goffredo, V.M.; Amato, B.; Setacci, C.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO) as a Rising-Star Metabolite: Implications for Human Health. Metabolites 2025, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, J.; Guo, J.; Dai, R.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Z. Targeting gut microbiota and immune crosstalk: Potential mechanisms of natural products in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1252907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.L.; Xue, Y.; Lai, X.H.; Du, D.Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.T. TMAO induces macrophage activation via the CD147/MMPs pathway. Chin. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2022, 38, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motte, L.R.; Giarritiello, F.; Sala, L.; Drago, L. A systematic review of TMAO, microRNAs, and the oral/gut microbiomes in atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction: Mechanistic insights and translational opportunities. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, I.; Saha, P.P.; Gupta, N.; Zhu, W.; Romano, K.A.; Skye, S.M.; Cajka, T.; Mohan, M.L.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; et al. A Cardiovascular Disease-Linked Gut Microbial Metabolite Acts via Adrenergic Receptors. Cell 2020, 180, 862–877.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Yuan, X. Gut microbiota on cardiovascular diseases-a mini review on current evidence. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1690411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, T.H.; Arifuzzaman, M.; Parkhurst, C.N.; Miranda, I.C.; Zhang, B.; Hu, E.; Kashyap, S.; Letourneau, J.; Jin, W.B.; Fu, Y.; et al. Host metabolism balances microbial regulation of bile acid signalling. Nature 2025, 638, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Hua, S.; Chen, X.; Ni, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, W.; Ding, A.; Qin, Z.; Yang, X.; et al. ZeXieYin formula alleviates atherosclerosis by regulating SBAs levels through the FXR/FGF15 pathway and restoring intestinal barrier integrity. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.H.; Liu, R.R.; Tang, L.; Chen, T. Interaction between gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism. Chin. J. Microecol. 2021, 33, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.L.; Wang, S.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, M.Y.; He, K.; Li, Q.; Huang, W.H.; Zhang, W. Effects of bile acids on the growth, composition and metabolism of gut bacteria. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnelli, V.B.; Ca, J.; Kandi, V.; Spandana, P.; Gr, M.; Hussain, M.H.; As, A.; Kavitha, R.; Jp, R.; Surendra Babu, T.; et al. The Role Played by Imidazole Propionic Acid in Modulating Gut-Heart Axis and the Development of Atherosclerosis: An Explorative Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e94362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundogdu, A.; Arikan, M.; Ulas, A.; Koldaş, S.S.; Ece, G. From dysbiosis to therapy: Shared gut microbial signatures and targeted interventions across liver, heart and brain disorders. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, K.; Jiang, C. Microbiota-derived bile acid metabolic enzymes and their impacts on host health. Cell Insight 2025, 4, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Besten, G.; van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Bakker, B.M. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda Torra, I.; Claudel, T.; Duval, C.; Kosykh, V.; Fruchart, J.C.; Staels, B. Bile acids induce the expression of the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha gene via activation of the farnesoid X receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yan, R.; Wang, R.; Zhang, P.; Bai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Butyrate suppresses atherosclerotic inflammation by regulating macrophages and polarization via GPR43/HDAC-miRNAs axis in ApoE-/- mice. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugii, S.; Olson, P.; Sears, D.D.; Saberi, M.; Atkins, A.R.; Barish, G.D.; Hong, S.H.; Castro, G.L.; Yin, Y.Q.; Nelson, M.C.; et al. PPARgamma activation in adipocytes is sufficient for systemic insulin sensitization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 22504–22509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, V.Z.; Folco, E.J.; Sukhova, G.; Shimizu, K.; Gotsman, I.; Vernon, A.H.; Libby, P. Interferon-gamma, a Th1 cytokine, regulates fat inflammation: A role for adaptive immunity in obesity. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.Y.; Yue, S.R.; Lu, A.P.; Zhang, L.; Ji, G.; Liu, B.C.; Wang, R.R. The improvement of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by Poria cocos polysaccharides associated with gut microbiota and NF-κB/CCL3/CCR1 axis. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2022, 103, 154208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosters, A.; Karpen, S.J. The role of inflammation in cholestasis: Clinical and basic aspects. Semin. Liver Dis. 2010, 30, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakadate, K.; Saitoh, H.; Sakaguchi, M.; Miruno, F.; Muramatsu, N.; Ito, N.; Tadokoro, K.; Kawakami, K. Advances in Understanding Lipopolysaccharide-Mediated Hepatitis: Mechanisms and Pathological Features. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, P.; Chandrasekaran, C.V.; Deepak, H.B.; Agarwal, A. Modulation of lipopolysaccha-ride-induced pro-inflammatory mediators by an extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra and its phytoconstituents. Inflammopharmacology 2011, 19, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Nie, S. Gut microbiota modulation by polysaccharide from Aloe gel: Potential prebiotic and targeted regulatory effects. Food Chem. 2025, 497, 147049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Zamora, L. Novel Ingredients: Hydroxytyrosol as a Neuroprotective Agent; What Is New on the Horizon? Foods 2025, 14, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, H.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Zhong, W.; Wen, B.; He, F.; Li, J. Reinventing gut health: Leveraging dietary bioactive compounds for the prevention and treatment of diseases. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1491821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Tian, J.; Li, J.T.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Akkermansia muciniphila alleviates metabolic disorders through gut microbiota-mediated tryptophan regulation. AMB Express 2025, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, L.; Duan, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Guo, J.; Li, K.; Shi, L.; Wong, W.T.; Cheung, P.C.K.; et al. Starch-EGCG complex enhances EGCG bioavailability through microbial metabolism and ameliorates metabolic-associated fatty liver disease via gut-liver axis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2026, 373, 124687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Huang, T.; Huang, D.; Liu, L.; Shen, C.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Liang, P.; et al. Licorice flavonoid alleviates gastric ulcers by producing changes in gut microbiota and promoting mucus cell regeneration. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 169, 115868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.H.; Wang, Z.X.; Zhou, D.; Han, Y.; Ma, F.; Hu, Z.; Xin, F.Z.; Liu, X.L.; Ren, T.Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. Sodium Butyrate Supplementation Inhibits Hepatic Steatosis by Stimulating Liver Kinase B1 and Insulin-Induced Gene. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 12, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, J.; Wang, M.; Yan, J.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, H. Resveratrol ameliorates liver fibrosis induced by nonpathogenic Staphylococcus in BALB/c mice through inhibiting its growth. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verediano, T.A.; Stampini Duarte Martino, H.; Dias Paes, M.C.; Tako, E. Effects of Anthocyanin on Intestinal Health: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, S.; Yuan, G.; Hu, H. Colon-targeted self-assembled nanoparticles loaded with berberine double salt ameliorate ulcerative colitis by improving intestinal mucosal barrier and gut microbiota. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 245, 114353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; Liu, X.Z.; Pan, W.; Zou, D.J. Berberine protects against diet-induced obesity through regulating metabolic endotoxemia and gut hormone levels. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 2765–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Role and Mechanism of the “Gut Microbiota-Endocannabinoid System” in Resveratrol Prevention and Treatment of NAFLD; Publication No. 2019283125. Ph.D. Thesis, Army Medical University, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chongqing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Q.; Zhang, S.; Ren, H.; Du, R.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, W. Ginsenoside Rg1 alleviates ANIT-induced intrahepatic cholestasis in rats via activating farnesoid X receptor and regulating transporters and metabolic enzymes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 324, 109062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Duan, Z.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, R.; Zhu, C.; Fan, D. Ginsenoside Rh4 inhibits colorectal cancer via the modulation of gut microbiota-mediated bile acid metabolism. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 72, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, W.J.; Yin, R.; Kang, X.W.; He, L.; Cao, X.; Chen, J. Berberine ameliorates high-fat diet-induced metabolic disorders through promoting gut Akkermansia and modulating bile acid metabolism. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Huang, C.; He, C.; Yang, T.; Ren, R.; Xin, Z.; Wang, X. Quercetin-Driven Akkermansia muciniphila Alleviates Obesity by Modulating Bile Acid Metabolism via an ILA/m6A/CYP8B1 Signaling. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2412865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Fang, B.; Kang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Qiang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, T.; Xiao, J.; Wang, M. Hepatoprotective Mechanism of Ginsenoside Rg1 against Alcoholic Liver Damage Based on Gut Microbiota and Network Pharmacology. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 5025237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, C.; Huang, H.; Wang, Q.; Huang, S.; He, Q.; Liu, X. Ginsenosides Rb1 Attenuates Chronic Social Defeat Stress-Induced Depressive Behavior via Regulation of SIRT1-NLRP3/Nrf2 Pathways. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 868833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y. Sulforaphane Regulates Glucose and Lipid Metabolisms in Obese Mice by Restraining JNK and Activating Insulin and FGF21 Signal Pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 13066–13079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; He, Z.; Liu, M.; Tan, J.; Zhang, H.; Hou, D.X.; He, J.; Wu, S. Dietary protocatechuic acid ameliorates inflammation and up-regulates intestinal tight junction proteins by modulating gut microbiota in LPS-challenged piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Yan, L.; Xu, J.; Liu, C.; Li, M.; Bai, F.; Yuan, F.; et al. Protocatechuic acid relieves ferroptosis in hepatic lipotoxicity and steatosis via regulating NRF2 signaling pathway. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2024, 40, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Kang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Fu, R.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shan, W.; et al. Sirtuin 3-mediated deacetylation of acyl-CoA synthetase family member 3 by protocatechuic acid attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 4166–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; He, Z.; Hao, W.; Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Ma, K.Y.; He, W.S.; Chen, Z.Y. Cholesterol-lowering activity of protocatechuic acid is mediated by increasing the excretion of bile acids and modulating gut microbiota and producing short-chain fatty acids. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 11557–11567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Romano, G.L.; Gozzo, L.; Laudani, S.; Paladino, N.; Dominguez Azpíroz, I.; Martínez López, N.M.; Giampieri, F.; Quiles, J.L.; Battino, M.; et al. Resveratrol and vascular health: Evidence from clinical studies and mechanisms of actions related to its metabolites produced by gut microbiota. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1368949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, G.; Chen, G.; Gao, H.; Lin, Y.; Liao, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Chi, Y.; Huang, Q.; Zhu, H.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits lipid accumulation in the intestine of atherosclerotic mice and macrophages. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 4313–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y. Resveratrol Reduces Hepatic ApoCIII Expression Through HNF-4α and FoxO1 to Affect Blood Lipids. Ph.D. Thesis, Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favari, C.; Rinaldi de Alvarenga, J.F.; Sánchez-Martínez, L.; Tosi, N.; Mignogna, C.; Cremonini, E.; Manach, C.; Bresciani, L.; Del Rio, D.; Mena, P. Factors driving the inter-individual variability in the metabolism and bioavailability of (poly)phenolic metabolites: A systematic review of human studies. Redox Biol. 2024, 71, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terao, J. Potential Role of Quercetin Glycosides as Anti-Atherosclerotic Food-Derived Factors for Human Health. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Moon, J.; Cho, Y.; Chung, J.H.; Shin, M.J. Quercetin up-regulates expressions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, liver X receptor α, and ATP binding cassette transporter A1 genes and increases cholesterol efflux in human macrophage cell line. Nutr. Res. 2013, 33, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zha, K.; Xi, X.; Li, J. Mechanism of quercetin against atherosclerosis via HMGB1/TLR4 pathway. Lab. Med. Clin. 2017, 14, 2511–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabeek, W.M.; Marra, M.V. Dietary Quercetin and Kaempferol: Bioavailability and Potential Cardiovascular-Related Bioactivity in Humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussagy, C.U.; Gonzalez-Miquel, M.; Santos-Ebinuma, V.C.; Pereira, J.F.B. Microbial torularhodin—A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2023, 43, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zheng, X.; Ji, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Guo, L.; Ye, K.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Y.J.; et al. The carotenoid torularhodin alleviates NAFLD by promoting Akkermanisa muniniphila-mediated adenosylcobalamin metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, H.; Wang, J.; Rui, J.; Wang, T.; Cai, Z.; Huang, S.; Gao, Y.; Ma, T.; Fan, R.; et al. Sensing ceramides by CYSLTR2 and P2RY6 to aggravate atherosclerosis. Nature 2025, 641, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Song, R.; Cao, Y.; Yan, X.; Gao, H.; Lian, F. Crocin mitigates atherosclerotic progression in LDLR knockout mice by hepatic oxidative stress and inflammatory reaction reduction, and intestinal barrier improvement and gut microbiota modulation. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 96, 105221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Zhang, G.; Li, M.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.; Wei, T.; et al. Panax notoginseng: Panoramagram of phytochemical and pharmacological properties, biosynthesis, and regulation and production of ginsenosides. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, N.; Tan, H.Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y. Gut-liver axis modulation of Panax notoginseng saponins in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 2021, 15, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.N.; Yang, Y.X.; Chen, Y.J.; He, S.L.; Yang, R.J.; Zhu, C.Y.; Du, C.C.; Zhang, D.D.; Wang, G.H.; Bian, Y.T.; et al. Tongmaijiangzhi formula and its hypolipidemic compounds attenuate hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis via AMPK/NF-κB pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 357, 120897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shang, Z.; Shen, A.; Huang, X.; Lu, A.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, T.; Lin, G.; Peng, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. Panax notoginseng saponin mitigates glycolysis to regulate macrophage polarization and sphingolipid metabolism via hypoxia-inducible factor-1 to alleviate atherosclerosis. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2025, 149, 157506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Liu, M.; Han, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, X.; Li, D.; Shi, Y.; Liu, B. Effects of Saponins on Lipid Metabolism: The Gut-Liver Axis Plays a Key Role. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, L.; Flórez, A.B.; Guadamuro, L.; Mayo, B. Effect of Soy Isoflavones on Growth of Representative Bacterial Species from the Human Gut. Nutrients 2017, 9, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Deng, Z.; Liang, L.; Yang, C.; Yan, J.; He, G. Multidimensional immunomodulation by abelmoschi corolla polysaccharide: Gut barrier restoration, microbiota remodelling, and systemic metabolic regulation. Phytomedicine: Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2025, 149, 157545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wu, R.; He, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Qin, P.; Yang, F.; Han, Y.; Hao, M.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Cohabitation facilitates microbiome shifts that promote isoflavone transformation to ameliorate liver injury. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 688–704.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polimeni, L.; Del Ben, M.; Baratta, F.; Perri, L.; Albanese, F.; Pastori, D.; Violi, F.; Angelico, F. Oxidative stress: New insights on the association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and atherosclerosis. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante-Menéndez, J.; González-López, P.; Huertas-Lárez, R.; Gómez-Hernández, A.; Escribano, Ó. Oxidative Stress Modulation by ncRNAs and Their Emerging Role as Therapeutic Targets in Atherosclerosis and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooli, R.G.R.; Mukhi, D.; Ramakrishnan, S.K. Oxidative Stress and Redox Signaling in the Pathophysiology of Liver Diseases. Compr. Physiol. 2022, 12, 3167–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, J.S.; Bhatti, G.K.; Reddy, P.H. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in metabolic disorders—A step towards mitochondria based therapeutic strategies, Biochimica et biophysica acta. Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teede, H.J.; Dalais, F.S.; Kotsopoulos, D.; Liang, Y.L.; Davis, S.; McGrath, B.P. Dietary soy has both beneficial and potentially adverse cardiovascular effects: A placebo-controlled study in men and postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 3053–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abshirini, M.; Omidian, M.; Kord-Varkaneh, H. Effect of soy protein containing isoflavones on endothelial and vascular function in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause 2020, 27, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fang, M.; Chen, Z.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, T.; Yu, L.; Ma, F.; Lu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; et al. High-phytosterol rapeseed oil prevents atherosclerosis by reducing intestinal barrier dysfunction and cholesterol uptake in ApoE-/- mice. Food Res. Int. 2025, 214, 116537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Tena, M.; Alegria, A.; Lagarda, M.; Venema, K. Impact of plant sterols enrichment dose on gut microbiota from lean and obese subjects using TIM-2 in vitro fermentation model. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 54, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscica, M.; Loh, W.J.; Sirtori, C.R.; Watts, G.F. Phytosterols and phytostanols in context: From physiology and pathophysiology to food supplementation and clinical practice. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 214, 107681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Guan, B.; Yu, L.; Liu, Q.; Hou, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, D.; Xu, H. Palmatine protects against atherosclerosis by gut microbiota and phenylalanine metabolism. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 209, 107413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Hu, J.; Geng, J.; Hu, T.; Wang, B.; Yan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, S. Berberine treatment reduces atherosclerosis by mediating gut microbiota in apoE-/- mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.L.; Qin, W.H.; Yang, D.D.; Ning, Y.Q.; Lin, S.; Dai, S.L.; Hu, B. Preventive and therapeutic effects of berberine on liver diseases and its mechanism. J. Clin. Hepatol. 2024, 40, 2326–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, D.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, M. Multi-Pharmacology of Berberine in Atherosclerosis and Metabolic Diseases: Potential Contribution of Gut Microbiota. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 709629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikebaier, J.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, B.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, L.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, S.-X. Bellidifolin, a constituent from edible Mongolic Liver Tea (Swertia diluta), promotes lipid metabolism by regulating intestinal microbiota and bile acid metabolism in mice during high fat diet-induced obesity. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Cui, W. Effects of Phytochemicals on Atherosclerosis: Based on the Gut–Liver Axis. Nutrients 2026, 18, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020188

Wang Y, Cui W. Effects of Phytochemicals on Atherosclerosis: Based on the Gut–Liver Axis. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020188

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yiming, and Weiwei Cui. 2026. "Effects of Phytochemicals on Atherosclerosis: Based on the Gut–Liver Axis" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020188

APA StyleWang, Y., & Cui, W. (2026). Effects of Phytochemicals on Atherosclerosis: Based on the Gut–Liver Axis. Nutrients, 18(2), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020188