Machine Learning-Driven Precision Nutrition: A Paradigm Evolution in Dietary Assessment and Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

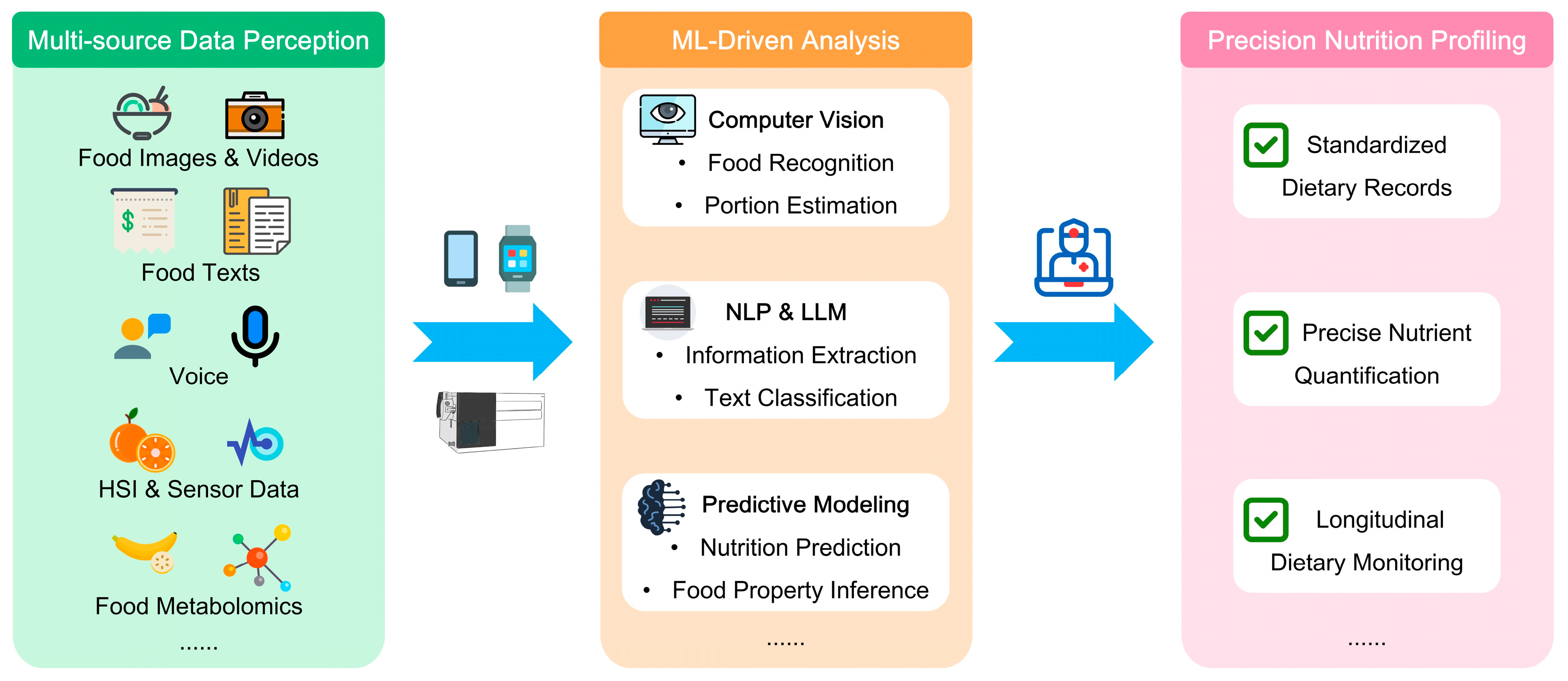

2. Objective and Automated Dietary Assessment

2.1. Multimodal Dietary Data Acquisition

2.2. Dynamic Nutrient Estimation: Transcending Static Tables

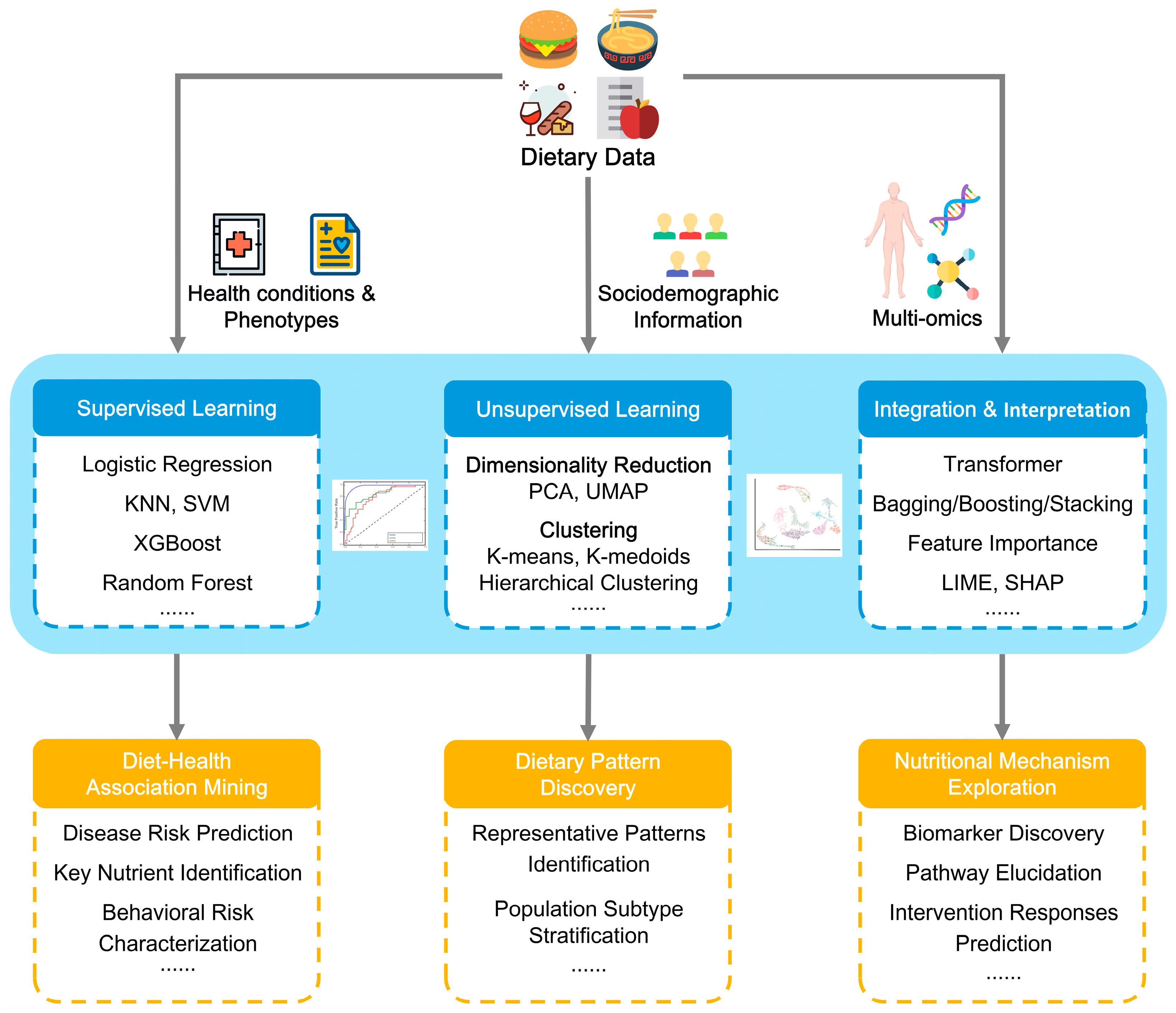

3. Deep Mining of Dietary Data: From Data to Insights

3.1. Diet-Health Associations Identification

3.2. Dietary Pattern Discovery

3.3. Nutritional Mechanisms and Biomarkers Exploration

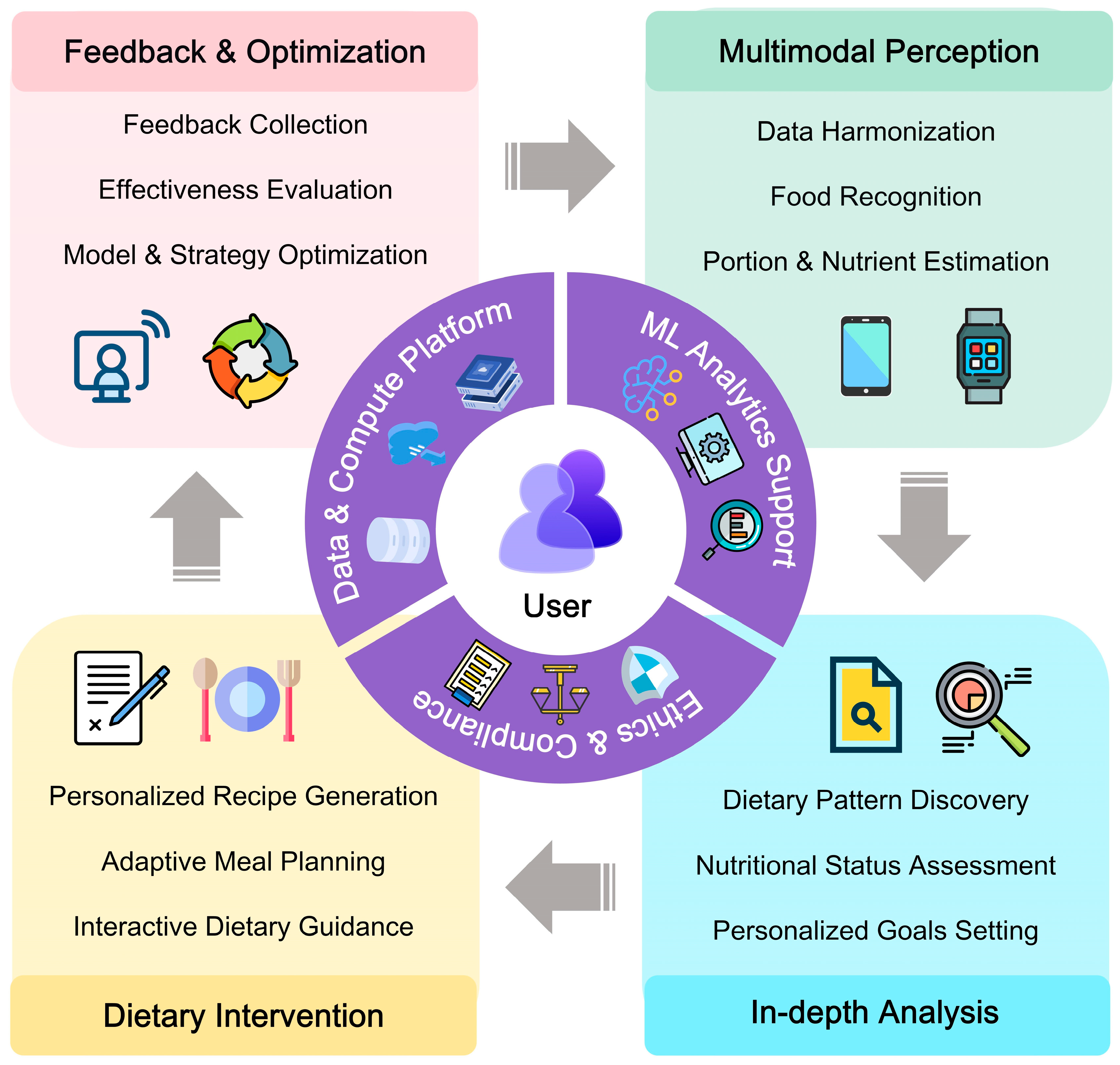

4. Personalized and Dynamic Dietary Intervention

4.1. Personalized Intervention: Data Integration for Customization

4.2. Dynamic Intervention: From Static Plans to Continuous Adaptation

4.3. Interactive and Explainable Dietary Recommendation

5. Current Impact, Challenges, and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiao, Y.-L.; Gong, Y.; Qi, Y.-J.; Shao, Z.-M.; Jiang, Y.-Z. Effects of dietary intervention on human diseases: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for The Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federation, W.O. World Obesity Atlas 2024. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/ (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Ferguson, L.R.; De Caterina, R.; Görman, U.; Allayee, H.; Kohlmeier, M.; Prasad, C.; Choi, M.S.; Curi, R.; de Luis, D.A.; Gil, Á.; et al. Guide and Position of the International Society of Nutrigenetics/Nutrigenomics on Personalised Nutrition: Part 1—Fields of Precision Nutrition. J. Nutr. Nutr. 2016, 9, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020–2030 Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research. Available online: https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/onr/strategic-plan (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Vadiveloo, M.K.; Juul, F.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Parekh, N. Perspective: Novel Approaches to Evaluate Dietary Quality: Combining Methods to Enhance Measurement for Dietary Surveillance and Interventions. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Yu, E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Understanding Nutritional Epidemiology and Its Role in Policy. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Ho, C.-T.; Gao, X.; Chen, N.; Chen, F.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X. Machine learning: An effective tool for monitoring and ensuring food safety, quality, and nutrition. Food Chem. 2025, 477, 143391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, M.B.E.; Robson, P.J.; Wallace, J.M.W. Issues in dietary intake assessment of children and adolescents. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, S213–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bzdok, D.; Altman, N.; Krzywinski, M. Statistics versus machine learning. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpaydin, E. Introduction to Machine Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, R.Y.; Coyner, A.S.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Chiang, M.F.; Campbell, J.P. Introduction to Machine Learning, Neural Networks, and Deep Learning. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaei Khoei, T.; Kaabouch, N. Machine Learning: Models, Challenges, and Research Directions. Future Internet 2023, 15, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Rahman, S.; Zhou, J.; Kang, J.J. A Comprehensive Review on Machine Learning in Healthcare Industry: Classification, Restrictions, Opportunities and Challenges. Sensors 2023, 23, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greener, J.G.; Kandathil, S.M.; Moffat, L.; Jones, D.T. A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaei Khoei, T.; Ould Slimane, H.; Kaabouch, N. Deep learning: Systematic review, models, challenges, and research directions. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 23103–23124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Wang, P.; Abbas, K. A survey on deep learning and its applications. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 40, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, H.; Wang, J. Exploring the relationship between hypertension and nutritional ingredients intake with machine learning. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2020, 7, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, A.; Ahammed, B. Machine learning algorithms for predicting malnutrition among under-five children in Bangladesh. Nutrition 2020, 78, 110861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; He, Q.; Li, Y. Machine learning-based prediction of vitamin D deficiency: NHANES 2001–2018. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1327058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.K.; Pitino, M.A.; Mahmood, R.; Zhu, I.Y.; Stone, D.; O’Connor, D.L.; Unger, S.; Chan, T.C.Y. Predicting Protein and Fat Content in Human Donor Milk Using Machine Learning. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabaş, A.; Ercan, U.; Kabas, O.; Moiceanu, G. Prediction of Selected Minerals in Beef-Type Tomatoes Using Machine Learning for Digital Agriculture. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachie, C.Y.E.; Obiri-Ananey, D.; Tawiah, N.A.; Attoh-Okine, N.; Aryee, A.N.A. Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting Fatty Acid Classes in Popular US Snacks Using NHANES Data. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjuik, T.A.; Boi-Dsane, N.A.A.; Kehinde, B.A. Enhancing dietary analysis: Using machine learning for food caloric and health risk assessment. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 8006–8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, A.; Das, D.; Chatterjee, T.N.; Tudu, B.; Roy, R.B. Regression-Based EGCG Detection in Green Tea Employing MIP Electrodes. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 18090–18097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshandara, S.; Franzoni, V.; Mezzetti, D.; Poggioni, V. Machine Learning Decision Support for Macronutrients in Neonatal Parenteral Nutrition. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 170001–170010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Wang, B. Food image classification and image retrieval based on visual features and machine learning. Multimed. Syst. 2022, 28, 2053–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbassuoni, S.; Ghattas, H.; El Ati, J.; Zoughby, Y.; Semaan, A.; Akl, C.; Trabelsi, T.; Talhouk, R.; Ben Gharbia, H.; Shmayssani, Z.; et al. Capturing children food exposure using wearable cameras and deep learning. PLoS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakopoulos, F.S.; Georga, E.I.; Fotiadis, D.I. An Automated Image-Based Dietary Assessment System for Mediterranean Foods. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med. Biol. 2023, 4, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Shen, H.; Choy, L.; Barakat, J.M.H. Smart Diet Diary: Real-Time Mobile Application for Food Recognition. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2023, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Min, W.; Hou, S.; Luo, M.; Li, T.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, S. Vision-based food nutrition estimation via RGB-D fusion network. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, W.J.; Liu, H.Q. Low-light image enhancement based on deep learning: A survey. Opt. Eng. 2022, 61, 040901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, R.; Xue, G. Predicting Unreported Micronutrients From Food Labels: Machine Learning Approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Ahmed, M.; L’Abbé, M.R. Natural language processing and machine learning approaches for food categorization and nutrition quality prediction compared with traditional methods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Duan, J. A Review of Large Language Models: Fundamental Architectures, Key Technological Evolutions, Interdisciplinary Technologies Integration, Optimization and Compression Techniques, Applications, and Challenges. Electronics 2024, 13, 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiri, F.Y.; Alahmadi, M.D.; Almuashi, M.A.; Almansour, A.M. Extract Nutritional Information from Bilingual Food Labels Using Large Language Models. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Wu, Y.; Yu, N.; Jia, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Backes, M.; Wang, Q.; Wei, C.-I. Integrating Vision-Language Models for Accelerated High-Throughput Nutrition Screening. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2403578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, C.T.; Adam, M.T.P.; Stewart, S.J.; Windus, J.L.; Rollo, M.E. Design of a Semi-Automated System for Dietary Assessment of Image-Voice Food Records. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 179823–179838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, F.P.W.; Qiu, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Xiao, B.; Yuan, W.; Giannarou, S.; Frost, G.; Lo, B. Dietary Assessment With Multimodal ChatGPT: A Systematic Analysis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 7577–7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargan, S.; Kumar, M.; Ayyagari, M.R.; Kumar, G. A Survey of Deep Learning and Its Applications: A New Paradigm to Machine Learning. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2020, 27, 1071–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Guan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lin, D.; Du, B. Effect of Different Cooking Methods on Nutrients, Antioxidant Activities and Flavors of Three Varieties of Lentinus edodes. Foods 2022, 11, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukumar, K.A.; Gupta, S.; Saikia, D. Leveraging machine learning techniques to analyze nutritional content in processed foods. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naravane, T.; Tagkopoulos, I. Machine learning models to predict micronutrient profile in food after processing. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Manickavasagan, A. Machine learning techniques for analysis of hyperspectral images to determine quality of food products: A review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.; Choi, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-C.; Cho, J.-S.; Moon, K.-D.; Park, T. Estimating the Composition of Food Nutrients from Hyperspectral Signals Based on Deep Neural Networks. Sensors 2019, 19, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Méndez, J.-J.; Luri Esplandiú, P.; Alonso-Santamaría, M.; Remirez-Moreno, B.; Urtasun Del Castillo, L.; Echavarri Dublán, J.; Almiron-Roig, E.; Sáiz-Abajo, M.-J. Hyperspectral imaging as a non-destructive technique for estimating the nutritional value of food. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawky, E.; Zhu, W.; Tian, J.; Abu El-Khair, R.A.; Selim, D.A. Metabolomics-Driven Prediction of Vegetable Food Metabolite Patterns: Advances in Machine Learning Approaches. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1051–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Birse, N.; Hong, Y.; Quinn, B.; Logan, N.; Jiao, Y.; Elliott, C.T.; Wu, D. Promoting LC-QToF based non-targeted fingerprinting and biomarker selection with machine learning for the discrimination of black tea geographical origin. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 142088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Xing, R.; Zhang, J.; Yu, N.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y. UPLC-QTOF-MS coupled with machine learning to discriminate between NFC and FC orange juice. Food Control 2023, 145, 109487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, L.; Ling, S.; Sha, Y.; Sun, H. Dietary intake of potassium, vitamin E, and vitamin C emerges as the most significant predictors of cardiovascular disease risk in adults. Medicine 2024, 103, e39180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, J.D.; Rosella, L.C.; Costa, A.P.; Anderson, L.N. Development of machine learning prediction models to explore nutrients predictive of cardiovascular disease using Canadian linked population-based data. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 47, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donghia, R.; Pesole, P.L.; Castellaneta, A.; Coletta, S.; Squeo, F.; Bonfiglio, C.; De Pergola, G.; Rinaldi, R.; De Nucci, S.; Giannelli, G.; et al. Age-Related Dietary Habits and Blood Biochemical Parameters in Patients with and without Steatosis—MICOL Cohort. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, N.; Nghiep, L.K.; Butsorn, A.; Khotprom, A.; Tudpor, K. Machine learning models identify micronutrient intake as predictors of undiagnosed hypertension among rural community-dwelling older adults in Thailand: A cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1411363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, R.; ZareMehrjardi, F.; Heidarzadeh-Esfahani, N.; Hughes, J.A.; Reid, R.E.R.; Borghei, M.; Ardekani, F.M.; Shahraki, H.R. Dietary intake of micronutrients are predictor of premenstrual syndrome, a machine learning method. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 55, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.R.; Gross, M.D.; Tapsell, L.C. Food synergy: An operational concept for understanding nutrition23. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1543S–1548S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedy, J.; Subar, A.F.; George, S.M.; Krebs-Smith, S.M. Extending Methods in Dietary Patterns Research. Nutrients 2018, 10, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, J.D.; Rosella, L.C.; Costa, A.P.; de Souza, R.J.; Anderson, L.N. Perspective: Big Data and Machine Learning Could Help Advance Nutritional Epidemiology. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, V.C.; Gorgulho, B.; Marchioni, D.M.; Araujo, T.A.d.; Santos, I.d.S.; Lotufo, P.A.; Benseñor, I.M. Clustering analysis and machine learning algorithms in the prediction of dietary patterns: Cross-sectional results of the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 35, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Houwelingen, M.L.; Zhu, Y. Identifying and predicting dietary patterns in the Dutch population using machine learning. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.; Kim, J.; Kim, W.C. Dietary Pattern Extraction Using Natural Language Processing Techniques. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 765794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noura, Q.; Khaoula El, K.; Nada, O.; Karima El, R.; Nour El Houda, C. Cluster analysis of dietary patterns associated with colorectal cancer derived from a Moroccan case–control study. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2023, 30, e100710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Momma, H.; Chen, H.; Nawrin, S.S.; Xu, Y.; Inada, H.; Nagatomi, R. Dietary patterns associated with the incidence of hypertension among adult Japanese males: Application of machine learning to a cohort study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 1293–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckart, A.C.; Sharma Ghimire, P. Exploring Predictors of Type 2 Diabetes Within Animal-Sourced and Plant-Based Dietary Patterns with the XGBoost Machine Learning Classifier: NHANES 2013–2016. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, C.; Joehanes, R.; Huan, T.; Levy, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Ma, J. Enhancing selection of alcohol consumption-associated genes by random forest. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 2058–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Chen, J.; Prescott, B.; Walker, M.E.; Grams, M.E.; Yu, B.; Vasan, R.S.; Floyd, J.S.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Smith, N.L.; et al. Plasma proteins associated with plant-based diets: Results from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study and Framingham Heart Study (FHS). Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1929–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, X.; Zuo, F.; Shi, H.; Jing, J. Artificial intelligence-based multi-omics analysis fuels cancer precision medicine. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 88, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, D.S.; Kang, S. Gene-diet interactions in carbonated sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and metabolic syndrome risk: A machine learning analysis in a large hospital-based cohort. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 64, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oghabian, A.; Kolk, B.W.D.; Marttinen, P.; Valsesia, A.; Langin, D.; Saris, W.H.; Astrup, A.; Blaak, E.E.; Pietiläinen, K.H. Baseline gene expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue predicts diet-induced weight loss in individuals with obesity. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, A.; Leclercq, M.; Droit, A.; Rudkowska, I.; Lebel, M. Predictive model for vitamin C levels in hyperinsulinemic individuals based on age, sex, waist circumference, low-density lipoprotein, and immune-associated serum proteins. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2024, 125, 109538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouraki, A.; Nogal, A.; Nocun, W.; Louca, P.; Vijay, A.; Wong, K.; Michelotti, G.A.; Menni, C.; Valdes, A.M. Machine Learning Metabolomics Profiling of Dietary Interventions from a Six-Week Randomised Trial. Metabolites 2024, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigsborg, K.; Stentoft-Larsen, V.; Demharter, S.; Aldubayan, M.A.; Trimigno, A.; Khakimov, B.; Engelsen, S.B.; Astrup, A.; Hjorth, M.F.; Dragsted, L.O.; et al. Predicting weight loss success on a new Nordic diet: An untargeted multi-platform metabolomics and machine learning approach. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1191944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Nasir, R.F.; Bell-Anderson, K.S.; Toniutti, C.A.; O’Leary, F.M.; Skilton, M.R. Biomarkers of dietary patterns: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1856–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Xu, Q.; Ma, X.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Sun, F. An interpretable machine learning model for precise prediction of biomarkers for intermittent fasting pattern. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 21, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Li, A.; Skilton, M.R. Development of a Multibiomarker Panel of Healthy Eating Index in United States Adults: A Machine Learning Approach. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, M.; Brassard, D.; Plante, P.-L.; Brière, F.; Corbeil, J.; Couture, P.; Lemieux, S.; Lamarche, B. Using machine learning to predict the consumption of a Mediterranean diet with untargeted metabolomics data from controlled feeding studies. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 104290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiherer, A.; Muendlein, A.; Mink, S.; Mader, A.; Saely, C.H.; Festa, A.; Fraunberger, P.; Drexel, H. Machine Learning Approach to Metabolomic Data Predicts Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Incidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snetselaar, L.G.; de Jesus, J.M.; DeSilva, D.M.; Stoody, E.E. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025: Understanding the Scientific Process, Guidelines, and Key Recommendations. Nutr. Today 2021, 56, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecil, J.E.; Barton, K.L. Inter-individual differences in the nutrition response: From research to recommendations. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trouwborst, I.; Gijbels, A.; Jardon, K.M.; Siebelink, E.; Hul, G.B.; Wanders, L.; Erdos, B.; Péter, S.; Singh-Povel, C.M.; de Vogel-van den Bosch, J.; et al. Cardiometabolic health improvements upon dietary intervention are driven by tissue-specific insulin resistance phenotype: A precision nutrition trial. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 71–83.e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhi, W.; Jahanvi, M.; Melony, B.; Parikh, M.M. Diet Recommendation System Using K-Means Clustering Algorithm of Machine Learning. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2024, 10, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, N.; Bhuvaneswari, S.; Kotecha, K.; Subramaniyaswamy, V. Hybrid Diet Recommender System Using Machine Learning Technique. In Proceedings of the Hybrid Intelligent Systems, online, 13–15 December 2022; pp. 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmageed, L.N.; Fathy, B.E.; Ali, R.E.; Borham, M.L. Enhancing Dietary Guidance with Machine Learning: A Stacking Classifier Approach to Personalized Nutrition. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Mobile, Intelligent, and Ubiquitous Computing Conference (MIUCC), Cairo, Egypt, 13–14 November 2024; pp. 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Vasuki, M.M. Developing a Machine Learning-Powered Dietary Guidance System for Diabetes Patients. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 4354–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookrah, R.; Dhowtal, J.D.; Nagowah, S.D. A DASH Diet Recommendation System for Hypertensive Patients Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 24–26 July 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, M.A.; Barrera-Machuca, A.A.; Calderon, N.; Wang, W.; Tausan, D.; Vayali, T.; Wishart, D.; Cullis, P.; Fraser, R. Value-based healthcare delivery through metabolomics-based personalized health platform. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2020, 33, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, M.L.; Goel, K.; Schneider, C.K.; Steullet, V.; Bratton, S.; Basch, E. National Implementation of an Artificial Intelligence–Based Virtual Dietitian for Patients With Cancer. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2024, 8, e2400085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, S.; Nidhyananthan, S.S.; Vanmathi, R.; Ramya, M. Diet Recommendation for Poly Cystic Ovarian Syndrome of Indian Patients Using Multi-Attribute and Multi-Labeling Classifier. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 13, 1660–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondevik, J.N.; Bennin, K.E.; Babur, Ö.; Ersch, C. A systematic review on food recommender systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogaveera, D.; Mathur, V.; Waghela, S. e-Health Monitoring System with Diet and Fitness Recommendation using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Coimbatore, India, 20–22 January 2021; pp. 694–700. [Google Scholar]

- Jagatheesaperumal, S.K.; Rajkumar, S.; Suresh, J.V.; Gumaei, A.H.; Alhakbani, N.; Uddin, M.Z.; Hassan, M.M. An IoT-Based Framework for Personalized Health Assessment and Recommendations Using Machine Learning. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarinda, K.; Deepa, N.; Dhamotharan, R.; Krishnan, R.S.; Raj, J.R.F.; Anchitaalagammai, J.V. Leveraging Machine Learning Algorithms to Optimize Diet Maintenance Based on User Food Intake and Fitness Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Sustainable Communication Networks and Application (ICSCNA), Theni, India, 11–13 December 2024; pp. 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, S.S.; Andrew, G.B. Introduction. In Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bignold, A.; Cruz, F.; Taylor, M.E.; Brys, T.; Dazeley, R.; Vamplew, P.; Foale, C. A conceptual framework for externally-influenced agents: An assisted reinforcement learning review. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 3621–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canese, L.; Cardarilli, G.C.; Di Nunzio, L.; Fazzolari, R.; Giardino, D.; Re, M.; Spanò, S. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning: A Review of Challenges and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shen, R.; Zheng, G.; Fu, X.; Yu, X.; Jiang, J. An interactive food recommendation system using reinforcement learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Sarani Rad, F.; Li, J. Delighting Palates with AI: Reinforcement Learning’s Triumph in Crafting Personalized Meal Plans with High User Acceptance. Nutrients 2024, 16, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achuthan, A.; Yii, S.H.; Alkhafaji, A. MyPlate: A Diet Monitoring and Recommender Application. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2024, 20, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawade, D.; Shah, J.; Gupta, E.; Panchal, J.; Shah, R. RecommenDiet: A System to Recommend a Dietary Regimen Using Facial Features. In Proceedings of the Advances in Distributed Computing and Machine Learning, Odisha, India, 15–16 January 2023; pp. 397–408. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, T.; Gao, J. RecipeRadar: An AI-Powered Recipe Recommendation System. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Systems and Applications, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 5–6 September 2024; pp. 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, B.U.; Joshnavalli, T.; Reddy, B.S.; Sreelaasya, A. An Advanced Deep Learning Approach for Dietary Recommendations using ROBERTA. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Intelligent Technologies (CONIT), Bangalore, India, 21–23 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, S.K.; Ali, R.H.; Faiz, S.; Khan, T.A. An Integrated AI Framework for Personalized Nutrition Using Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing for Dietary Recommendations. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, M.; Shi, X.; Li, G. KG-DietNet: A Personalized Dietary Recommendation System Based on Knowledge Graphs and Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 12th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC), Chongqing, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 833–837. [Google Scholar]

- Ataguba, G.; Orji, R. Exploring Large Language Models for Personalized Recipe Generation and Weight-Loss Management. ACM Trans. Comput. Healthc. 2025, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Khatibi, E.; Nagesh, N.; Abbasian, M.; Azimi, I.; Jain, R.; Rahmani, A.M. ChatDiet: Empowering personalized nutrition-oriented food recommender chatbots through an LLM-augmented framework. Smart Health 2024, 32, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopitar, L.; Bedrač, L.; Strath, L.J.; Bian, J.; Stiglic, G. Improving Personalized Meal Planning with Large Language Models: Identifying and Decomposing Compound Ingredients. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, A.; Dong, F.; Gu, F.; Gama, J.; Zhang, G. Learning under Concept Drift: A Review. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2019, 31, 2346–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alluhaidan, A.S.; Bashir, R.N.; Jahangir, R.; Marzouk, R.; Saidani, O.; Alroobaea, R. Machine Learning and Fog Computing-Enabled Sensor Drift Management in Precision Agriculture. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 36953–36970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, K.; Lan, W.; Gu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Yang, X.; Qin, W.; Han, D. An AI Dietitian for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Management Based on Large Language and Image Recognition Models: Preclinical Concept Validation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e51300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaladejo, L.; Giai, J.; Deronne, C.; Baude, R.; Bosson, J.-L.; Bétry, C. Assessing real-life food consumption in hospital with an automatic image recognition device: A pilot study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 68, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaina, L.; Palmieri, E.; Lucarini, I.; Maiolo, L.; Maita, F. Toward a User-Accessible Spectroscopic Sensing Platform for Beverage Recognition Through K-Nearest Neighbors Algorithm. Sensors 2025, 25, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rein, M.; Ben-Yacov, O.; Godneva, A.; Shilo, S.; Zmora, N.; Kolobkov, D.; Cohen-Dolev, N.; Wolf, B.-C.; Kosower, N.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; et al. Effects of personalized diets by prediction of glycemic responses on glycemic control and metabolic health in newly diagnosed T2DM: A randomized dietary intervention pilot trial. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamanna, P.; Joshi, S.; Thajudeen, M.; Shah, L.; Poon, T.; Mohamed, M.; Mohammed, J. Personalized nutrition in type 2 diabetes remission: Application of digital twin technology for predictive glycemic control. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1485464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, C.J.; Hu, L.; Kharmats, A.Y.; Curran, M.; Berube, L.; Wang, C.; Pompeii, M.L.; Illiano, P.; St-Jules, D.E.; Mottern, M.; et al. Effect of a Personalized Diet to Reduce Postprandial Glycemic Response vs a Low-fat Diet on Weight Loss in Adults With Abnormal Glucose Metabolism and Obesity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2233760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhu, H.; Wang, W.; Ren, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, S.; Sun, S.; Zhu, Z.; Gorriz, J.M.; et al. Deep learning in food category recognition. Inf. Fusion 2023, 98, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-i.; Kwon, S.O.; Do, J.A.; Ra, S.; Yoon, J. Harmonization, standardization and integration of food and nutrient database in Korea: Open government data at the public data portal. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 148, 108118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, C.; Camtepe, S. Precision health data: Requirements, challenges and existing techniques for data security and privacy. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 129, 104130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P.; Vachon, F.; Ayanso, A. Reducing data privacy breaches: An empirical study of relevant antecedents and an outcome. Inf. Technol. People 2024, 38, 1712–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Ryu, K.; Kim, J.-Y.; Lee, S. Application of privacy protection technology to healthcare big data. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241282242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Wilmanski, T.; Diener, C.; Earls, J.C.; Zimmer, A.; Lincoln, B.; Hadlock, J.J.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Magis, A.T.; et al. Multiomic signatures of body mass index identify heterogeneous health phenotypes and responses to a lifestyle intervention. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkoum, H.; Idri, A.; Abnane, I. Global and local interpretability techniques of supervised machine learning black box models for numerical medical data. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 131, 107829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Bobadilla, A.V.; Schmitt, V.; Maier, C.S.; Mensing, S.; Stodtmann, S. Practical guide to SHAP analysis: Explaining supervised machine learning model predictions in drug development. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Yacub, Z.; Shasha, D. DietNerd: A Nutrition Question-Answering System That Summarizes and Evaluates Peer-Reviewed Scientific Articles. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsampos, I.; Marakakis, E. DietQA: A Comprehensive Framework for Personalized Multi-Diet Recipe Retrieval Using Knowledge Graphs, Retrieval-Augmented Generation, and Large Language Models. Computers 2025, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Luo, H.; Lu, J.; Liu, D.; Posluszny, H.; Dhaliwal, M.P.; MacLeod, J.; Qin, Y.; Yang, C.; Hartman, T.J.; et al. DietAI24 as a framework for comprehensive nutrition estimation using multimodal large language models. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imantho, H.; Seminar, K.B.; Damayanthi, E.; Suyatma, N.E.; Priandana, K.; Ligar, B.W.; Seminar, A.U. An Intelligent Food Recommendation System for Dine-in Customers with Non-Communicable Diseases History. J. Keteknikan Pertan. 2024, 12, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Min, W.; Zhou, P.; Mei, S.; Jiang, S. Dietary Recommendation Based on Multi-objective Optimization Integrating Nutritional Knowledge and Preference-Health Balance. Food Sci. 2025, 46, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Task Type | Metric | Definition | Formula | Pros/Cons | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Accuracy | Proportion of correctly predicted samples. | Fails in imbalanced classes | Exploration of the hypertension-nutrient intake relationship [19] | |

| Recall | Proportion of true positives among actual positives. | Recall and Precision are inversely related | |||

| Precision | Proportion of true positives among predicted positives | ||||

| F1 score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall | Balances precision and recall | |||

| Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC-AUC) | ROC curve plots True Positive Rate (TPR) vs. False Positive Rate (FPR). Higher values (closer to 1) indicate better performance. | Robust to class imbalance | |||

| Cohen’s Kappa coefficient | Agreement between a model’s predictions and true labels while accounting for random chance. | Suitable for multi-class tasks | Prediction of malnutrition in children [20] | ||

| Brier score (BS) | It quantifies probabilistic prediction accuracy. Lower values (closer to 0) indicate better performance. | Suitable for probability outputs | Prediction of vitamin D deficiency [21] | ||

| Regression | Mean absolute error (MAE) | Average absolute error between predicted values and true values | Less penalty on large errors | Prediction of human milk nutrient content [22] | |

| Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) | Average relative error between predicted values and true values | Undefined for zero true values | Prediction of minerals in tomatoes [23] | ||

| Mean squared error (MSE) | Average squared error between predicted values and true values | Penalizes large errors | Prediction of snack fatty acid content [24] | ||

| Root mean square error (RMSE) | Square root of MSE | Penalizes large errors; Matches the unit of the target | Prediction of food calories [25] | ||

| Mean squared logarithmic error (MSLE) | Average squared difference between the logarithm of predicted values and true values | Suitable for large value ranges | Prediction of epigallocatechin-3-gallate content in green tea [26] | ||

| R2 (Coefficient of determination) | It measures how well the model fits the observed data. Higher values (closer to 1) indicate better performance. | Less effective for non-linear relationships | Neonatal parenteral nutrition management [27] |

| Task | Authors | Machine Learning Algorithms | Applications | Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment | Wei et al. [28] | Faster R-CNN | Food image retrieval and classification | Accuracy = 0.754 |

| Elbassuoni et al. [29] | CNN | Recording children’s food intake | Precision = 82.23–93.57% | |

| Konstantakopoulos et al. [30] | EfficientNetB2 | Automated image-based dietary assessment | Accuracy = 83.8%; MAPE = 10.5% | |

| Nadeem et al. [31] | Faster R-CNN | Food recognition & calorie calculation | Accuracy = 80.1%; Calorie error ≤ 10% | |

| Shao et al. [32] | RGB-D fusion network | Vision-based automated food nutrient analysis | Mean PMAE = 18.5% | |

| Razavi et al. [34] | RF, KNN, LR, Neural Networks, SVM, etc. | Predicting unreported micronutrient contents from food label information | R2 = 0.28 (for magnesium) −0.92 (for manganese) | |

| Hu et al. [35] | BERT, Elastic net, KNN, XGBoost | Food classification and calculation of nutritional quality using label information | Predicting food major categories: Accuracy = 0.98; FSANZ score prediction: R2 = 0.87 and MSE = 14.4 | |

| Assiri et al. [37] | GPT-4v, GPT-4o, and Gemini | Extracting nutritional elements/values from food labels in English and Arabic | GPT-4o and GPT-4v: median Accuracy = 83–87% (English) | |

| Ma et al. [38] | CLIP, MLP | Estimating nutrient contents from food images and labels | Lipid quantification: macro-AUCROC = 0.921 | |

| Lo et al. [40] | GPT-4v | Food recognition, portion estimation, and nutritional analysis | Food Detection: Accuracy = 0.936; F1 score = 0.946 | |

| Muthukumar et al. [43] | SVR, RF | Predicting protein content in plant foods after processing | NMSE = 0.13 | |

| Naravane et al. [44] | MLP, LASSO, Elastic net, Gradient boost, RF, DT | Predicting micronutrient contents in processed foods | R2 = 0.42–0.95 | |

| Marín-Méndez et al. [47] | Multivariate linear regression, LASSO, Ridge regression, Elastic net, KNN, etc. | Predicting nutrition values of processed foods using hyperspectral imaging and machine learning | Near infrared (NIR): Protein: R2 = 0.88 | |

| Data Mining | Wang et al. [51] | XGBoost, KNN, RF, etc. | Cardiovascular disease risk assessment according to micronutrient intake | AUC = 0.952 |

| Morgenstern et al. [52] | Conditional Inference Forests | Developing the cardiovascular disease prediction model using dietary data | AUROC = 0.821 | |

| Silva et al. [59] | K-means, SVM, KNN, etc. | Identifying dietary patterns and predicting them using sociodemographic data | Two patterns were identified; Accuracy = 69–72% | |

| Houwelingen et al. [60] | K-means, K-medoids, and hierarchical clustering; Naïve Bayes, KNN, RF, etc | Identifying and predicting dietary patterns in the Dutch population | K-means Clustering: Silhouette score = 0.045 (males) and 0.054 (females); Classification: Accuracy = 60–68% | |

| Choi et al. [61] | LDA | Extracting dietary patterns in the Korean population | Three patterns were identified. | |

| Noura et al. [62] | PCA, K-means, LR | Identifying CRC-related dietary patterns in the Moroccan population | Two patterns were identified. OR = 1.59 | |

| Li et al. [63] | UMAP, K-means, LR | Assessing dietary patterns and their association with incident hypertension | Four patterns were identified. OR = 0.39 (Dairy/vegetable-based); OR = 0.37 (Meat-based) | |

| Eckart et al. [64] | PCA, XGBoost | Exploring Predictors of Type 2 Diabetes Within Dietary Patterns | Accuracy = 83.4%; AUROC = 68% | |

| Park et al. [68] | XGBoost, DNN | Exploring gene-diet interactions in carbonated sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and metabolic syndrome risk | AUROC = 0.860 (XGBoost) and 0.92 (DNN) | |

| Oghabian et al. [69] | SVM | Predicting weight loss outcomes using gene expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue | Max AUC = 0.74, 95% confidence intervals (CIs): 0.62–0.86 | |

| Mahdavi et al. [70] | KNN, Linear regression | Predicting VC levels in hyperinsulinemia patients | Correlation coefficient = 68.5% ± 9.8% | |

| Kouraki et al. [71] | Elastic net, RF, LR | Comparing serum and fecal metabolomic changes after inulin or Omega-3 supplementation | Serum metabolites: Elastic net regression: AUC = 0.87; Fecal metabolites: Elastic net regression: AUC = 0.86 | |

| Pigsborg et al. [72] | QLattice | Weight loss prediction after New Nordic Diet intervention | ROC-AUC = 0.81 | |

| Hu et al. [74] | DT, KNN, RF, SVM, Naive Bayes | Exploring the potential biomarkers of intermittent fasting via metabolomics | Random Forest: AUC = 0.99, Accuracy = 0.94 | |

| Liang et al. [75] | LASSO, Elastic net, the Gradient Boosting Regression, XGBoost, RF, MLP | Developing a panel of objective biomarkers that reflects the Healthy Eating Index | Primary multi-biomarker panel: RMSE = 10.10, R2 = 0.163 (LASSO, 10-fold cross-validation) | |

| Côté et al. [76] | RF and DT | Predicting Mediterranean diet consumption using plasma metabolomics | RF: Accuracy of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.71–0.86) | |

| Leiherer et al. [77] | RF, SVM, Naive Bayes, etc. | Predicting cardiovascular risk within 4 years using serum metabolomics | F1 score = 50%; Specificity = 93% | |

| Dietary Intervention | Nidhi et al. [81] | K-means | Diet recommendation leveraging users’ age, height, BMI, and dietary preferences | Accuracy = 96% |

| Vignesh et al. [82] | K-means, RF, MLP, RNN, LSTM | Automatic diet recommendation according to BMI and food preferences | Accuracy = 0.98 | |

| Abdelmageed et al. [83] | RF, LSTM, KNN, SVM, etc. | Providing tailored nutrition advice with BMI, BMR, and TDEE | F1 score = 94%, and ROCAUC = 97% | |

| Vasuki et al. [84] | DT, RF, Neural Networks | Dietary guidance system for diabetes patients | Neural Networks: Accuracy = 0.90, F1 score = 0.90. | |

| Mogaveera et al. [90] | C4.5, ID3 | Providing diet and exercise recommendations | Diet: Accuracy = 93.55% (C4.5, Prediabetes) | |

| Jagatheesaperumal et al. [91] | RF, CatBoost, LR, MLP | Providing diet and exercise recommendations based on health indicators | CatBoost: F1 score = 1 | |

| Clarinda et al. [92] | ANN, MLP, DT, GBM | Providing personalized dietary recommendations by analyzing food intake and fitness data | Accuracy = 92.8%; Precision = 91.2% | |

| Liu et al. [96] | PPO, LGCN, SGNN, etc. | Interactive food recommendation | Precision = 93.2%; NDCG = 95.71% | |

| Amiri et al. [97] | DQN | Providing personalized and adaptable meal plans | Average Acceptance Score = 4.5/5.0 | |

| Achuthan et al. [98] | Mask R-CNN | Food identification, portion analysis, calorie calculation, and food recommendation | Food Image Recognition: Average Precision = 0.825 | |

| Pawade et al. [99] | FaceNet, KNN | Recommending diet plans based on facial features | Height, weight, and BMI estimation: RMSE = 6.2 | |

| Aydın et al. [102] | RF, GB, Mistral 7B | Dynamic dietary recommendation | Calorie Prediction: R2 = 0.108; Structured Information Extraction: Accuracy = 91% | |

| Liu et al. [103] | GNN, GPT-4 | Personalized dietary recommendation | Calorie Prediction: Percentage of error = 3.2%; User satisfaction: personalized alignment = 4.8/5.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Quan, W.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Du, L. Machine Learning-Driven Precision Nutrition: A Paradigm Evolution in Dietary Assessment and Intervention. Nutrients 2026, 18, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010045

Quan W, Zhou J, Wang J, Huang J, Du L. Machine Learning-Driven Precision Nutrition: A Paradigm Evolution in Dietary Assessment and Intervention. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuan, Wenbin, Jingbo Zhou, Juan Wang, Jihong Huang, and Liping Du. 2026. "Machine Learning-Driven Precision Nutrition: A Paradigm Evolution in Dietary Assessment and Intervention" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010045

APA StyleQuan, W., Zhou, J., Wang, J., Huang, J., & Du, L. (2026). Machine Learning-Driven Precision Nutrition: A Paradigm Evolution in Dietary Assessment and Intervention. Nutrients, 18(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010045