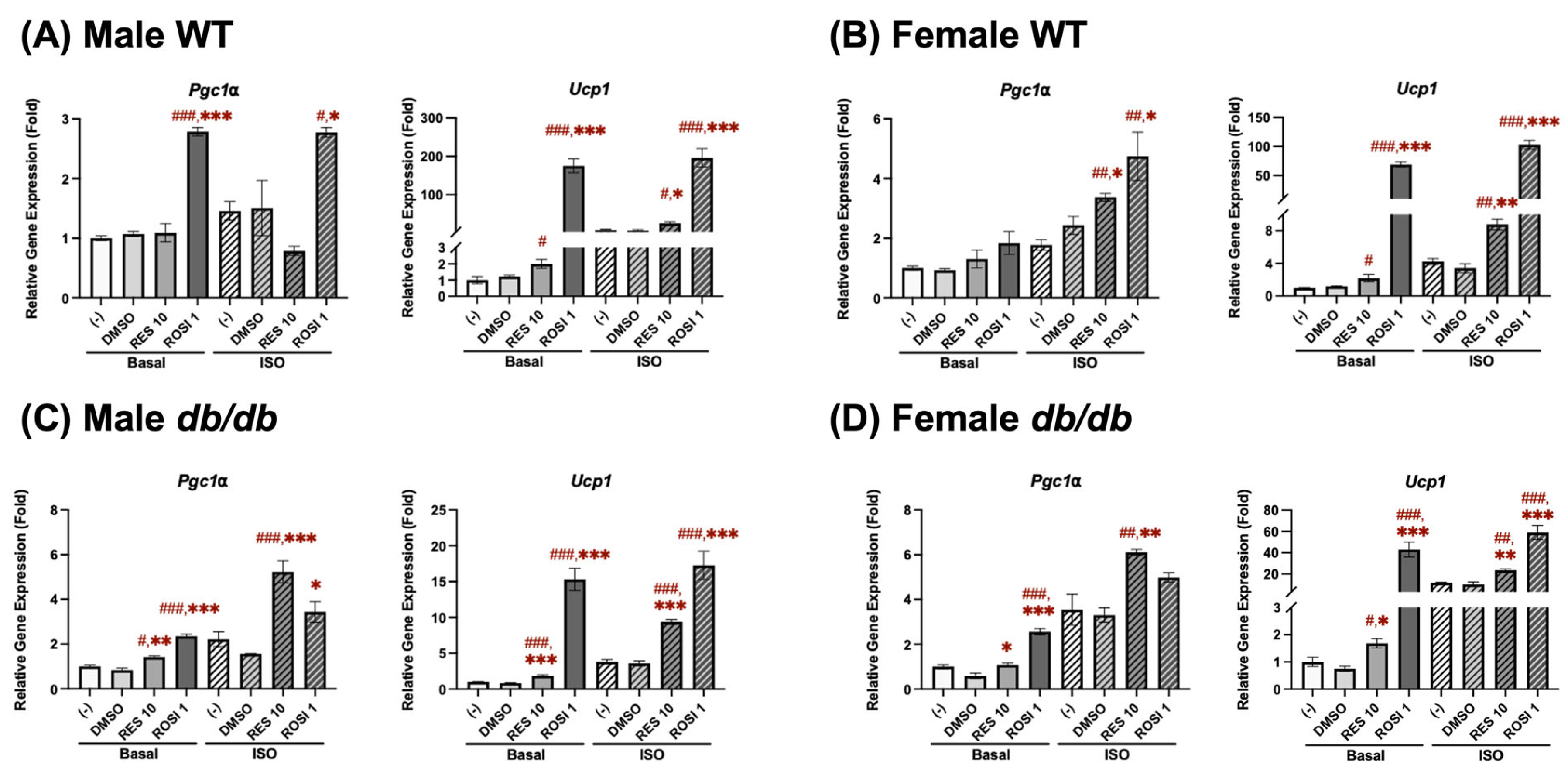

Figure 1.

RES induced browning by increasing Pgc1α and Ucp1 mRNA expression in the differentiated ADSCs derived from (A) male WT, (B) female WT, (C) male db/db, and (D) female db/db mice. The ADSCs were isolated from subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice aged 10–12 weeks. Pgc1α and Ucp1 mRNA expression was measured in pooled ADSCs from 3 to 5 mice following 7-day differentiation in the presence or absence of either resveratrol (RES, 10 µM), rosiglitazone (ROSI, a positive control, 1 µM), or the vehicle control (DMSO). Isoproterenol (ISO, 1 µM) was added for the final 6 h to activate brown-like adipocytes. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for all statistical analyses in basal or ISO-stimulated conditions. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the negative control (−) group, while *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 1.

RES induced browning by increasing Pgc1α and Ucp1 mRNA expression in the differentiated ADSCs derived from (A) male WT, (B) female WT, (C) male db/db, and (D) female db/db mice. The ADSCs were isolated from subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice aged 10–12 weeks. Pgc1α and Ucp1 mRNA expression was measured in pooled ADSCs from 3 to 5 mice following 7-day differentiation in the presence or absence of either resveratrol (RES, 10 µM), rosiglitazone (ROSI, a positive control, 1 µM), or the vehicle control (DMSO). Isoproterenol (ISO, 1 µM) was added for the final 6 h to activate brown-like adipocytes. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for all statistical analyses in basal or ISO-stimulated conditions. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the negative control (−) group, while *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 2.

Fold changes in thermogenic gene expression following ISO and RES treatment in the adipocytes derived from ADSCs of male and female WT and db/db mice. (A) Fold Changes in Pgc1α and (C) Ucp1 mRNA expression in response to ISO stimulation were calculated for all groups. (B) Fold Changes in Pgc1α and (D) Ucp1 mRNA expression in response to RES relative to the DMSO were calculated under basal or ISO-stimulated conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis in (A,C); two-way ANOVA was used in (B,D). ##, ### indicate p < 0.01 and p < 0.001 for comparisons between males and females. *** indicates p < 0.001 for comparisons between WT and db/db mice. ††, ††† indicate p < 0.01 and p < 0.001 for comparisons between basal and ISO conditions.

Figure 2.

Fold changes in thermogenic gene expression following ISO and RES treatment in the adipocytes derived from ADSCs of male and female WT and db/db mice. (A) Fold Changes in Pgc1α and (C) Ucp1 mRNA expression in response to ISO stimulation were calculated for all groups. (B) Fold Changes in Pgc1α and (D) Ucp1 mRNA expression in response to RES relative to the DMSO were calculated under basal or ISO-stimulated conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis in (A,C); two-way ANOVA was used in (B,D). ##, ### indicate p < 0.01 and p < 0.001 for comparisons between males and females. *** indicates p < 0.001 for comparisons between WT and db/db mice. ††, ††† indicate p < 0.01 and p < 0.001 for comparisons between basal and ISO conditions.

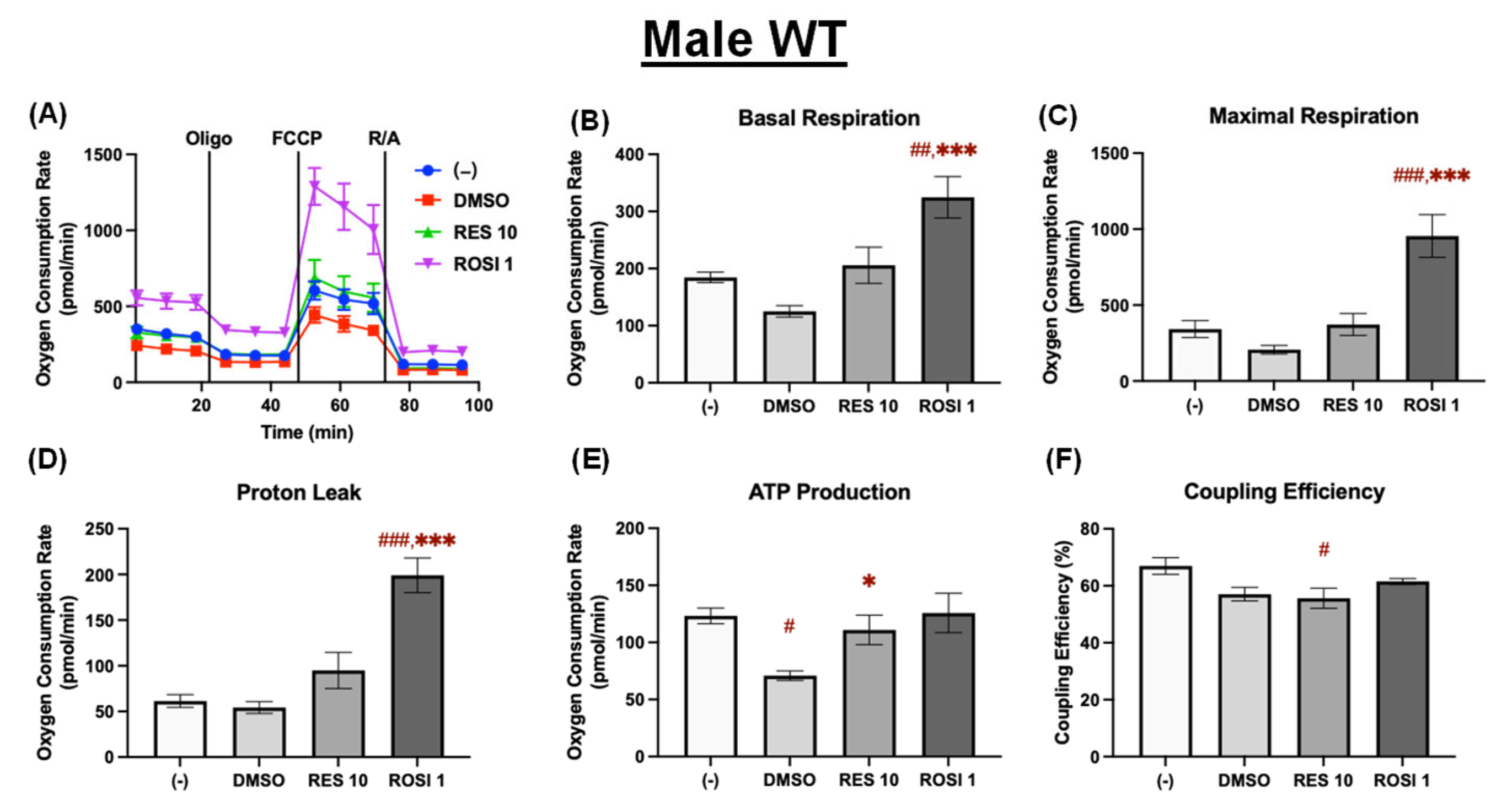

Figure 3.

RES enhanced mitochondrial uncoupling in the differentiated ADSCs from male WT mice. The ADSCs were first differentiated in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (1 µM), or DMSO for 7 days, then were reseeded into a Seahorse XFe assay plate. The cells underwent real-time oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements for a mitochondrial stress test after reseeding. (A) OCR recordings over time, (B) basal respiration, (C) maximal respiration, (D) proton leak, (E) ATP production, and (F) coupling efficiency are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group, while *, *** indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 3.

RES enhanced mitochondrial uncoupling in the differentiated ADSCs from male WT mice. The ADSCs were first differentiated in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (1 µM), or DMSO for 7 days, then were reseeded into a Seahorse XFe assay plate. The cells underwent real-time oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements for a mitochondrial stress test after reseeding. (A) OCR recordings over time, (B) basal respiration, (C) maximal respiration, (D) proton leak, (E) ATP production, and (F) coupling efficiency are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group, while *, *** indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 compared to the DMSO group.

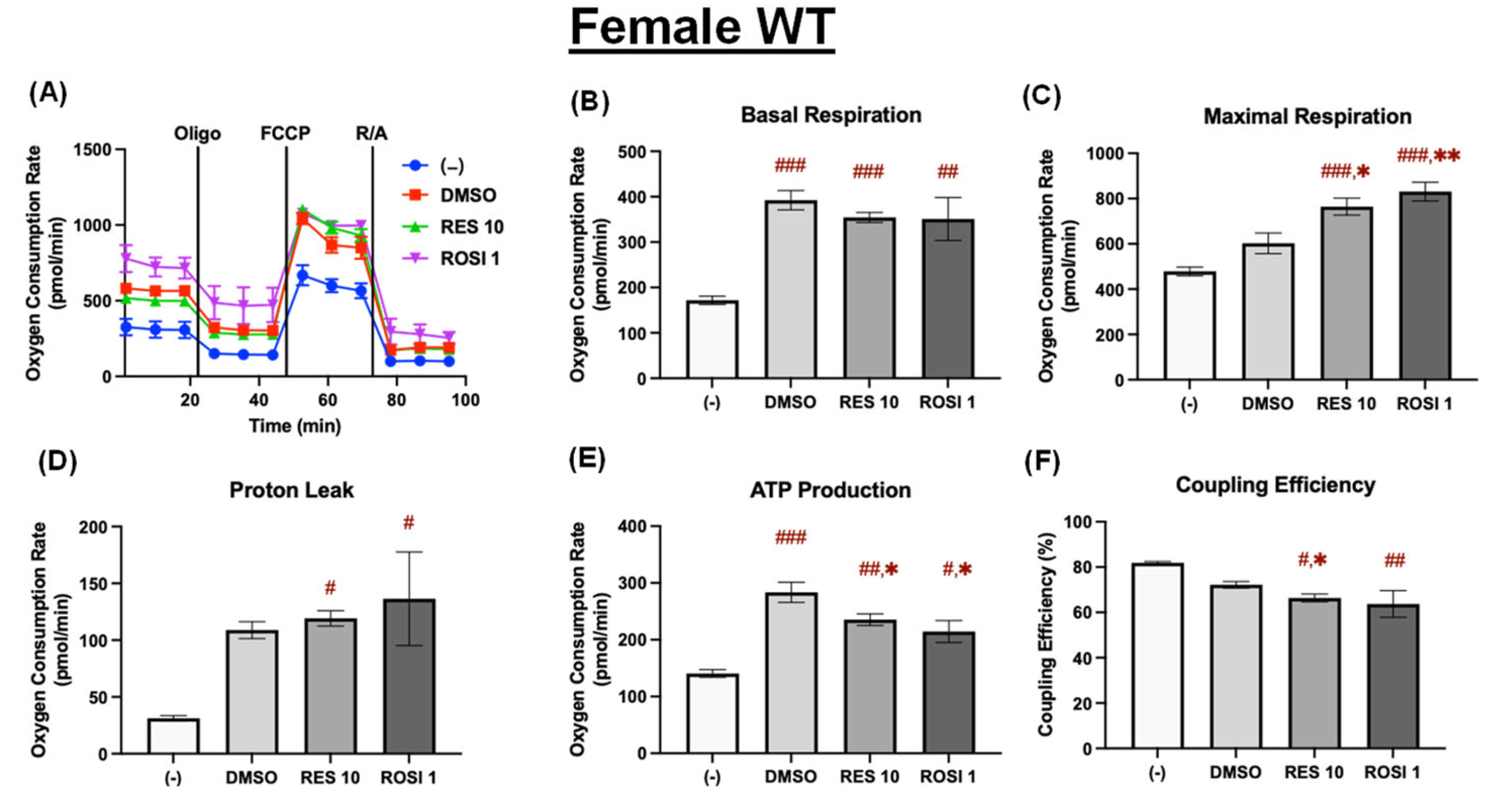

Figure 4.

RES enhanced mitochondrial uncoupling in the differentiated ADSCs from female WT mice. The ADSCs were first differentiated in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (1 µM), or DMSO for 7 days, then were reseeded into a Seahorse XFe assay plate. The cells underwent real-time oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements for a mitochondrial stress test after reseeding. (A) OCR recordings over time, (B) basal respiration, (C) maximal respiration, (D) proton leak, (E) ATP production, and (F) coupling efficiency are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group, while *, ** indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 4.

RES enhanced mitochondrial uncoupling in the differentiated ADSCs from female WT mice. The ADSCs were first differentiated in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (1 µM), or DMSO for 7 days, then were reseeded into a Seahorse XFe assay plate. The cells underwent real-time oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements for a mitochondrial stress test after reseeding. (A) OCR recordings over time, (B) basal respiration, (C) maximal respiration, (D) proton leak, (E) ATP production, and (F) coupling efficiency are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group, while *, ** indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the DMSO group.

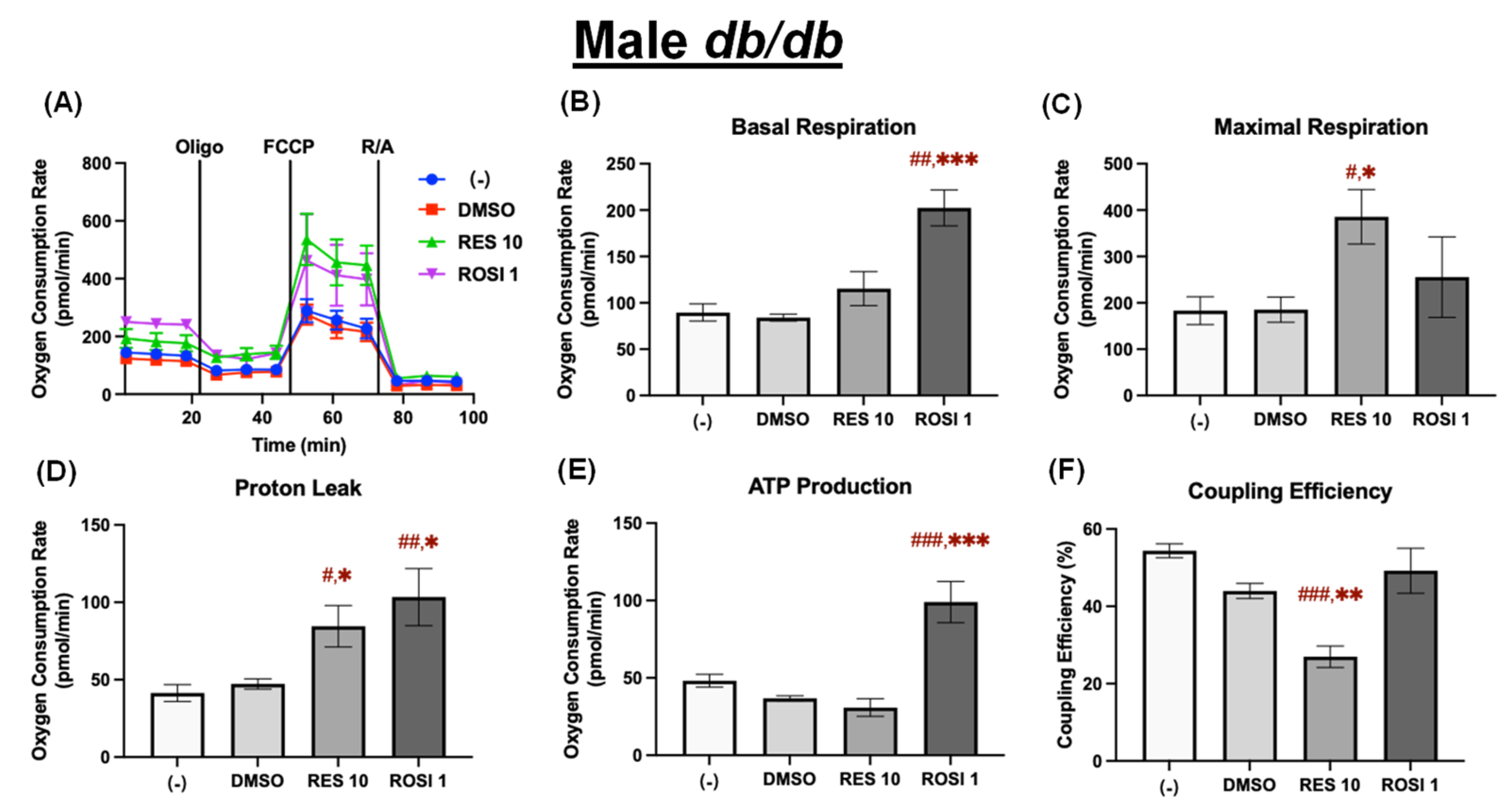

Figure 5.

RES enhanced mitochondrial uncoupling in the differentiated ADSCs from male db/db mice. The ADSCs were first differentiated in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (1 µM), or DMSO for 7 days, then were reseeded into a Seahorse XFe assay plate. The cells underwent real-time oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements for a mitochondrial stress test after reseeding. (A) OCR recordings over time, (B) basal respiration, (C) maximal respiration, (D) proton leak, (E) ATP production, and (F) coupling efficiency are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group, while *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 5.

RES enhanced mitochondrial uncoupling in the differentiated ADSCs from male db/db mice. The ADSCs were first differentiated in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (1 µM), or DMSO for 7 days, then were reseeded into a Seahorse XFe assay plate. The cells underwent real-time oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements for a mitochondrial stress test after reseeding. (A) OCR recordings over time, (B) basal respiration, (C) maximal respiration, (D) proton leak, (E) ATP production, and (F) coupling efficiency are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group, while *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 6.

RES enhanced mitochondrial uncoupling in the differentiated ADSCs from female db/db mice. The ADSCs were first differentiated in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (1 µM), or DMSO for 7 days, then were reseeded into a Seahorse XFe assay plate. The cells underwent real-time oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements for a mitochondrial stress test after reseeding. (A) OCR recordings over time, (B) basal respiration, (C) maximal respiration, (D) proton leak, (E) ATP production, and (F) coupling efficiency are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group, while *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 6.

RES enhanced mitochondrial uncoupling in the differentiated ADSCs from female db/db mice. The ADSCs were first differentiated in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (1 µM), or DMSO for 7 days, then were reseeded into a Seahorse XFe assay plate. The cells underwent real-time oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements for a mitochondrial stress test after reseeding. (A) OCR recordings over time, (B) basal respiration, (C) maximal respiration, (D) proton leak, (E) ATP production, and (F) coupling efficiency are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group, while *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the DMSO group.

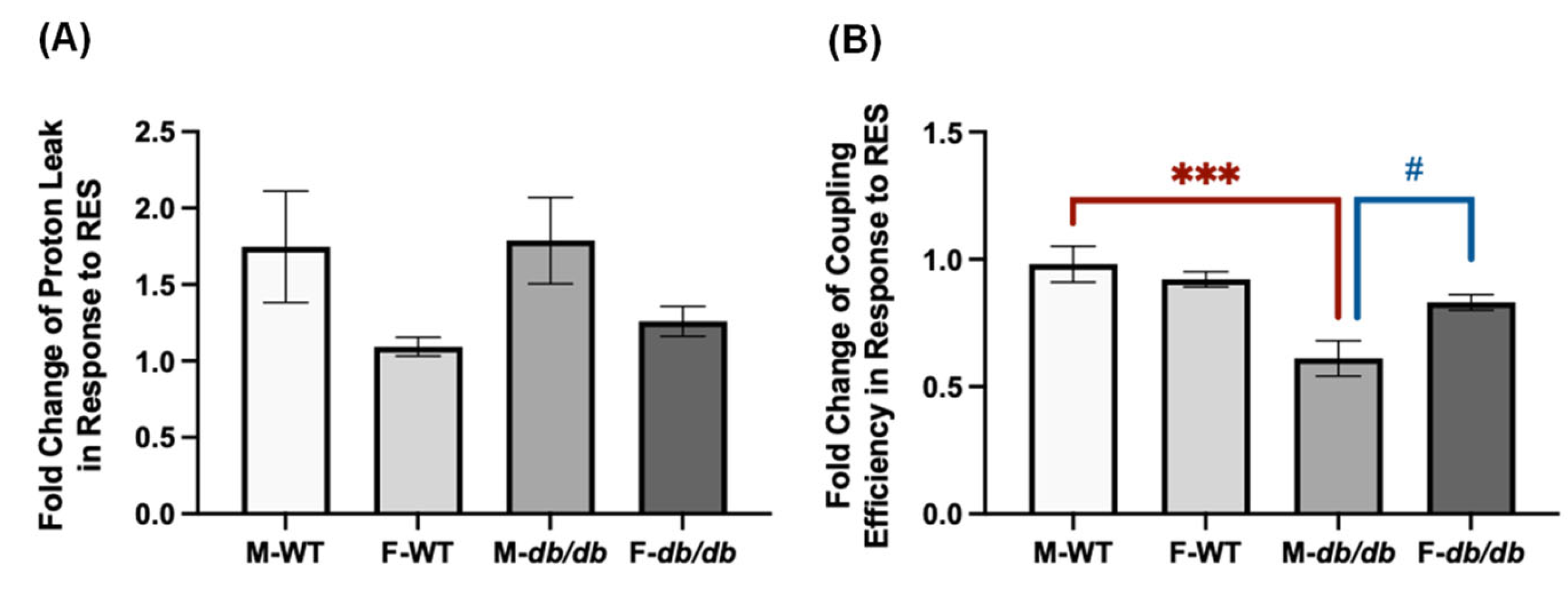

Figure 7.

Fold changes in proton leak and coupling efficiency following RES treatment in the differentiated ADSCs from male and female WT and db/db mice. (A) Fold changes in proton leak and (B) coupling efficiency in response to RES relative to DMSO were calculated for each of the 4 groups, highlighting sex-specific responses and differences between the WT and db/db. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. # indicates p < 0.05 in the comparison between sexes, and *** indicates p < 0.001 in the comparison between the WT and db/db mice.

Figure 7.

Fold changes in proton leak and coupling efficiency following RES treatment in the differentiated ADSCs from male and female WT and db/db mice. (A) Fold changes in proton leak and (B) coupling efficiency in response to RES relative to DMSO were calculated for each of the 4 groups, highlighting sex-specific responses and differences between the WT and db/db. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. # indicates p < 0.05 in the comparison between sexes, and *** indicates p < 0.001 in the comparison between the WT and db/db mice.

Figure 8.

RES improved insulin signaling in the differentiated ADSCs from male WT mice. The ADSCs from the male WT mice were differentiated for 7 days in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (a positive control, 1 μM), or DMSO, followed by overnight starvation in DMEM/high glucose without FBS. Cells were then stimulated with or without insulin (50 nM) for 20 min, and protein lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (A) Total AKT, p-AKT (ser473), and their respective loading control ERK1/2 are shown. The left panel corresponds to the basal condition (−Insulin), and the right panel to the insulin-stimulated condition (+Insulin). Quantifications of total AKT/ERK1/2 (B), p-AKT/ERK1/2 (C), and p-AKT/total AKT (D) are presented as fold changes relative to the (−) group under basal conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. # and ## indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the (−) group. * and ** indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 8.

RES improved insulin signaling in the differentiated ADSCs from male WT mice. The ADSCs from the male WT mice were differentiated for 7 days in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (a positive control, 1 μM), or DMSO, followed by overnight starvation in DMEM/high glucose without FBS. Cells were then stimulated with or without insulin (50 nM) for 20 min, and protein lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (A) Total AKT, p-AKT (ser473), and their respective loading control ERK1/2 are shown. The left panel corresponds to the basal condition (−Insulin), and the right panel to the insulin-stimulated condition (+Insulin). Quantifications of total AKT/ERK1/2 (B), p-AKT/ERK1/2 (C), and p-AKT/total AKT (D) are presented as fold changes relative to the (−) group under basal conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. # and ## indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the (−) group. * and ** indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the DMSO group.

![Nutrients 18 00019 g008 Nutrients 18 00019 g008]()

Figure 9.

RES improved insulin signaling in the differentiated ADSCs from female WT mice. The ADSCs from the female WT mice were differentiated for 7 days in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (a positive control, 1 μM), or DMSO, followed by overnight starvation in DMEM/high glucose without FBS. Cells were then stimulated with or without insulin (50 nM) for 20 min, and protein lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (A) Total AKT, p-AKT (ser473), and their respective loading control ERK1/2 are shown. The left panel corresponds to the basal condition (−Insulin), and the right panel to the insulin-stimulated condition (+Insulin). Quantifications of total AKT/ERK1/2 (B), p-AKT/ERK1/2 (C), and p-AKT/total AKT (D) are presented as fold changes relative to the (−) group under basal conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. # indicates p < 0.05 compared to the (−) group. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 9.

RES improved insulin signaling in the differentiated ADSCs from female WT mice. The ADSCs from the female WT mice were differentiated for 7 days in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (a positive control, 1 μM), or DMSO, followed by overnight starvation in DMEM/high glucose without FBS. Cells were then stimulated with or without insulin (50 nM) for 20 min, and protein lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (A) Total AKT, p-AKT (ser473), and their respective loading control ERK1/2 are shown. The left panel corresponds to the basal condition (−Insulin), and the right panel to the insulin-stimulated condition (+Insulin). Quantifications of total AKT/ERK1/2 (B), p-AKT/ERK1/2 (C), and p-AKT/total AKT (D) are presented as fold changes relative to the (−) group under basal conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. # indicates p < 0.05 compared to the (−) group. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to the DMSO group.

![Nutrients 18 00019 g009 Nutrients 18 00019 g009]()

Figure 10.

The effects of RES on insulin signaling in the differentiated ADSCs from male db/db mice. The ADSCs from male db/db mice were differentiated for 7 days in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (a positive control, 1 μM), or DMSO, followed by overnight starvation in DMEM/high glucose without FBS. Cells were then stimulated with or without insulin (50 nM) for 20 min. Protein lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (A) Total AKT, p-AKT (ser473), and their respective loading control ERK1/2 are shown. The left panel represents the basal condition (−Insulin), and the right panel shows the insulin-stimulated condition (+Insulin). Quantifications of total AKT/ERK1/2 (B), p-AKT/ERK1/2 (C), and p-AKT/total AKT (D) are presented as fold changes relative to the (−) group under basal conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. # and ## indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the (−) group. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 10.

The effects of RES on insulin signaling in the differentiated ADSCs from male db/db mice. The ADSCs from male db/db mice were differentiated for 7 days in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (a positive control, 1 μM), or DMSO, followed by overnight starvation in DMEM/high glucose without FBS. Cells were then stimulated with or without insulin (50 nM) for 20 min. Protein lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (A) Total AKT, p-AKT (ser473), and their respective loading control ERK1/2 are shown. The left panel represents the basal condition (−Insulin), and the right panel shows the insulin-stimulated condition (+Insulin). Quantifications of total AKT/ERK1/2 (B), p-AKT/ERK1/2 (C), and p-AKT/total AKT (D) are presented as fold changes relative to the (−) group under basal conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. # and ## indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the (−) group. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to the DMSO group.

![Nutrients 18 00019 g010 Nutrients 18 00019 g010]()

Figure 11.

The effects of RES on insulin signaling in the differentiated ADSCs from female db/db mice. The ADSCs from the female db/db mice were differentiated for 7 days in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (a positive control, 1 μM), or DMSO, followed by overnight starvation in DMEM/high glucose without FBS. Cells were then stimulated with or without insulin (50 nM) for 20 min, and protein lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (A) Total AKT, p-AKT (ser473), and their respective loading control ERK1/2 are shown. The left panel corresponds to the basal condition (−Insulin), and the right panel to the insulin-stimulated condition (+Insulin). Quantifications of total AKT/ERK1/2 (B), p-AKT/ERK1/2 (C), and p-AKT/total AKT (D) are presented as fold changes relative to the (−) group under basal conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group. *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the DMSO group.

Figure 11.

The effects of RES on insulin signaling in the differentiated ADSCs from female db/db mice. The ADSCs from the female db/db mice were differentiated for 7 days in the presence or absence of RES (10 µM), ROSI (a positive control, 1 μM), or DMSO, followed by overnight starvation in DMEM/high glucose without FBS. Cells were then stimulated with or without insulin (50 nM) for 20 min, and protein lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (A) Total AKT, p-AKT (ser473), and their respective loading control ERK1/2 are shown. The left panel corresponds to the basal condition (−Insulin), and the right panel to the insulin-stimulated condition (+Insulin). Quantifications of total AKT/ERK1/2 (B), p-AKT/ERK1/2 (C), and p-AKT/total AKT (D) are presented as fold changes relative to the (−) group under basal conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. #, ##, and ### indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the (−) group. *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, compared to the DMSO group.

![Nutrients 18 00019 g011 Nutrients 18 00019 g011]()

Figure 12.

Fold changes in insulin sensitivity markers following insulin and RES treatment in the differentiated ADSCs from male and female WT and db/db mice. (A) Fold changes in p-AKT/ERK and (C) p-AKT/AKT in response to insulin were calculated for all groups. (B) Fold changes in p-AKT/ERK and (D) p-AKT/AKT in response to RES relative to the DMSO group under basal and insulin-stimulated conditions were calculated. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis in (A,C), and two-way ANOVA was used in (B,D). ## indicates p < 0.01 for comparisons between males and females, while ** indicates p < 0.01 for comparisons between WT and db/db mice. † and †† indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 for comparisons between basal and insulin conditions.

Figure 12.

Fold changes in insulin sensitivity markers following insulin and RES treatment in the differentiated ADSCs from male and female WT and db/db mice. (A) Fold changes in p-AKT/ERK and (C) p-AKT/AKT in response to insulin were calculated for all groups. (B) Fold changes in p-AKT/ERK and (D) p-AKT/AKT in response to RES relative to the DMSO group under basal and insulin-stimulated conditions were calculated. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis in (A,C), and two-way ANOVA was used in (B,D). ## indicates p < 0.01 for comparisons between males and females, while ** indicates p < 0.01 for comparisons between WT and db/db mice. † and †† indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 for comparisons between basal and insulin conditions.