The Relationship Between Children’s Diet and Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

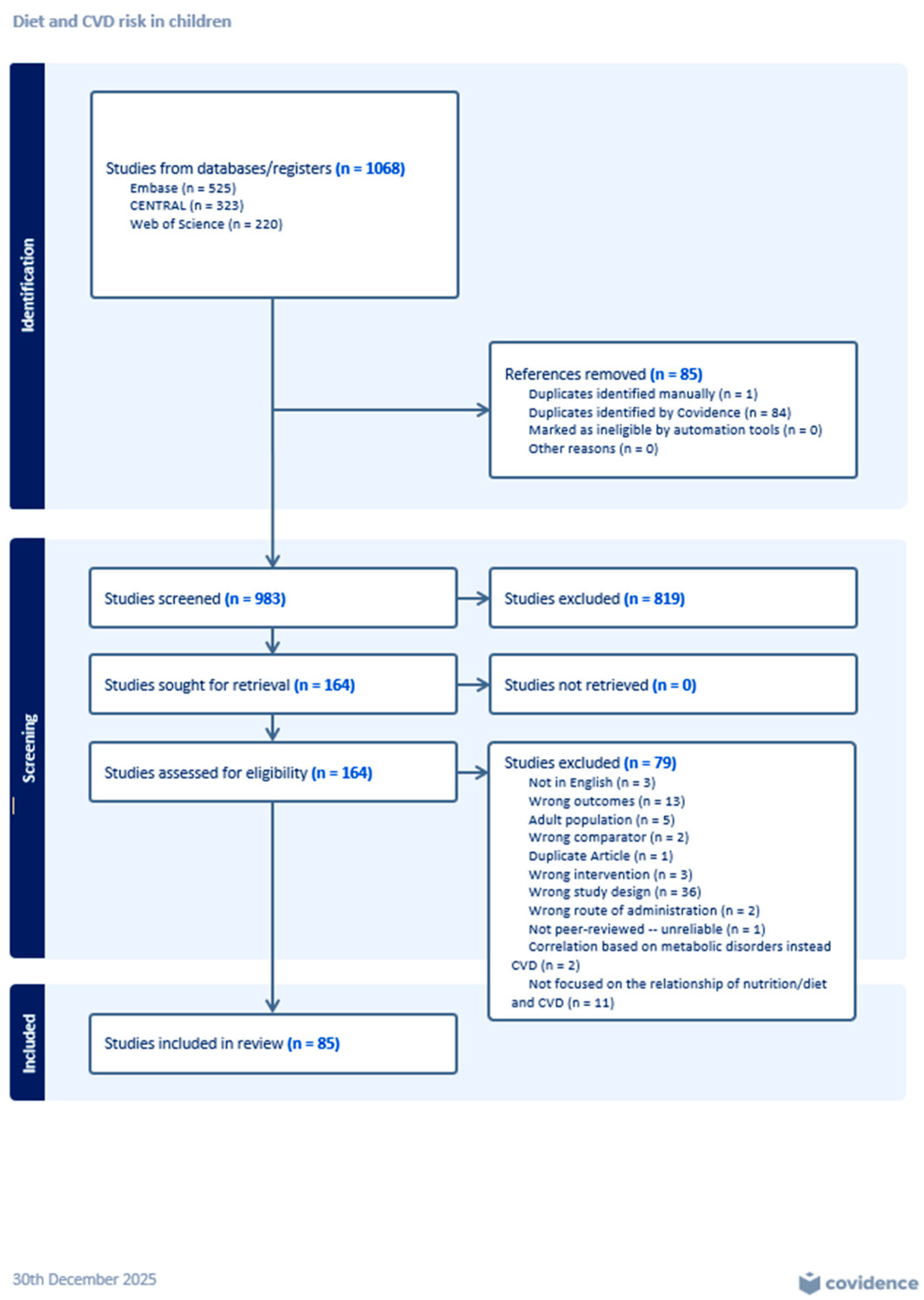

3.1. Screening and Review Process

3.2. Measuring Dietary Intake and Eating Patterns

3.3. Measurement of Outcome Variables

3.4. Diet and Blood Pressure (Systolic and/or Diastolic)

3.4.1. Elementary School Age (5–11 Years Old)

3.4.2. Middle School Age (12–14 Years Old)

3.4.3. High School Age (15–18 Years Old)

3.4.4. Elementary, Middle School Age (5–14 Years Old)

3.4.5. Middle, High School Age (12–18 Years Old)

3.4.6. Elementary, Middle, High School Age (5–18 Years Old)

3.5. Diet and Lipoproteins (HDL, LDL, TC)

3.5.1. Elementary School Age (5–11 Years Old)

3.5.2. Middle School Age (12–14 Years Old)

3.5.3. High School Age (12–14 Years Old)

3.5.4. Elementary, Middle School Age (5–14 Years Old)

3.5.5. Middle, High School Age (12–18 Years Old)

3.5.6. Elementary, Middle, High School Age (5–18 Years Old)

3.6. Diet and TGs

3.6.1. Elementary School Age (5–11 Years Old)

3.6.2. Middle School Age (12–14 Years Old)

3.6.3. High School Age (15–18 Years Old)

3.6.4. Elementary, Middle School Age (5–14 Years Old)

3.6.5. Middle, High School Age (12–18 Years Old)

3.6.6. Elementary, Middle, High School Age (5–18 Years Old)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| CM | Cardiometabolic |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| HDL | High-Density lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low-Density lipoprotein |

| TC | Total Cholesterol |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| UPFs | Ultra-Processed Foods |

References

- Di Cesare, M.; Perel, P.; Taylor, S.; Kabudula, C.; Bixby, H.; Gaziano, T.A.; McGhie, D.V.; Mwangi, J.; Pervan, B.; Narula, J.; et al. The Heart of the World. Glob. Heart 2024, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ferranti, S.D.; Steinberger, J.; Ameduri, R.; Baker, A.; Gooding, H.; Kelly, A.S.; Mietus-Snyder, M.; Mitsnefes, M.M.; Peterson, A.L.; St-Pierre, J.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in High-Risk Pediatric Patients: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e603–e634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.M.; Ramphul, K.; Dachepally, R.; Almasri, M.; Memon, R.A.; Sakthivel, H.; Zaman, A.; Ahmed, R.; Shahid, F. Five-Year Trends in Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease among Adolescents in the United States. Arch. Med. Sci. Atheroscler. Dis. 2024, 9, e56–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelino, M.; Tagi, V.M.; Chiarelli, F. Cardiovascular Risk in Children: A Burden for Future Generations. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, J.; Daniels, S.R.; Hagberg, N.; Isasi, C.R.; Kelly, A.S.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; Pate, R.R.; Pratt, C.; Shay, C.M.; Towbin, J.A.; et al. Cardiovascular Health Promotion in Children: Challenges and Opportunities for 2020 and Beyond: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 134, e236–e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiechl, S.J.; Staudt, A.; Stock, K.; Gande, N.; Bernar, B.; Hochmayr, C.; Winder, B.; Geiger, R.; Griesmacher, A.; Egger, A.E.; et al. Diagnostic Yield of a Systematic Vascular Health Screening Approach in Adolescents at Schools. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2022, 70, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.; Dastmalchi, L.N.; Gulati, M.; Michos, E.D. A Heart-Healthy Diet for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: Where Are We Now? Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Li, W.; Duan, N.; Hu, X.; Yao, N.; Yu, G.; Qu, J. Relationship Between Salt Intake and Cardiovascular Disease. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2025, 27, e70078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, S.; Lotfaliany, M.; Machado, P.; Hodge, A.; Gamage, E.; Levy, R.B.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Redfern, J.; O’Neil, A.; Marx, W.; et al. Exposure to Ultra-Processed Food and Risk of Cardiovascular Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 1564–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murni, I.K.; Sulistyoningrum, D.C.; Susilowati, R.; Julia, M.; Dickinson, K.M. The Association between Dietary Intake and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors among Obese Adolescents in Indonesia. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, N.; Abd Majid, H.; Toumpakari, Z.; Carroll, H.A.; Yazid Jalaludin, M.; Al Sadat, N.; Johnson, L. The Association of Breakfast Frequency and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk Factors among Adolescents in Malaysia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, B.; Verma, A.; Singh, K.; Sharma, S.; Bansal, R.; Tandon, R.; Goyal, A.; Singh, B.; Chhabra, S.T.; Aslam, N.; et al. Prevalence of Sustained Hypertension and Obesity among Urban and Rural Adolescents: A School-Based, Cross-Sectional Study in North India. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leermakers, E.T.M.; Felix, J.F.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Raat, H.; Franco, O.H.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C. Sugar-Containing Beverage Intake at the Age of 1 Year and Cardiometabolic Health at the Age of 6 Years: The Generation R Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein Bdair, B.W.; Al-Graittee, S.J.R.; Jabbar, M.S.; Kadhim, Z.H.; Lawal, H.; Alwa’aly, S.H.; Kadhim Abutiheen, A.A. Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Hypertension and Diabetes among Overweight and Obese Adolescents in the City of Kerbala, Iraq. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. Res. 2020, 11, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Saber, N.; Teymoori, F.; Kazemi Jahromi, M.; Mokhtari, E.; Norouzzadeh, M.; Farhadnejad, H.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F. From Adolescence to Adulthood: Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Cardiometabolic Health in a Prospective Cohort Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundaram, P.; Avulakunta, I.D. Human Growth and Development. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, P.; Henrikson, N.B.; Morrison, C.C.; Dunn, J.; Nguyen, M.; Blasi, P.; Whitlock, E.P. Lipid Screening in Childhood for Detection of Multifactorial Dyslipidemia: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2016.

- Li, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zou, Z.; Gao, D.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Dong, B.; Ma, J. Association between Pubertal Development and Elevated Blood Pressure in Children. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2021, 23, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik, M.; Starzyk, J.B.; Drożdż, M.; Drożdż, D. Effects of Puberty on Blood Pressure Trajectories—Underlying Processes. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2023, 25, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, M.A.; Mihalopoulos, N.L.; Holubkov, R.; Dai, S.; Labarthe, D.R. Changes in Fasting Lipids during Puberty. J. Pediatr. 2016, 170, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, W. Association of Health Behaviors in Life’s Essential 8 and Hypertension in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study from the NHANES Database. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgoni, V.L.; Brauchla, M.; Fleige, L.; Chu, Y. Association of Whole-Grain and Dietary Fiber Intake with Cardiometabolic Risk in Children and Adolescents. Nutr. Health 2020, 26, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethna, C.B.; Alanko, D.; Wirth, M.D.; Shivappa, N.; Hebert, J.R.; Khan, S.; Sen, S. Dietary Inflammation and Cardiometabolic Health in Adolescents. Pediatr. Obes. 2021, 16, e12706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian-Almarcegui, C.; Vandevijvere, S.; Gottrand, F.; Beghin, L.; Dallongeville, J.; Sjostrom, M.; Leclercq, C.; Manios, Y.; Widhalm, K.; De Morares, A.C.F.; et al. Association of Heart Rate and Blood Pressure among European Adolescents with Usual Food Consumption: The HELENA Study. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc Dis. 2016, 26, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gimeno, G.; Seral-Cortes, M.; Sabroso-Lasa, S.; Esteban, L.M.; Widhalm, K.; Gottrand, F.; Stehle, P.; Meirhaeghe, A.; Muntaner, M.; Kafatos, A.; et al. Interplay of the Mediterranean Diet and Genetic Hypertension Risk on Blood Pressure in European Adolescents: Findings from the HELENA Study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 2101–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seral-Cortes, M.; Sabroso-Lasa, S.; De Miguel-Etayo, P.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Gesteiro, E.; Molina-Hidalgo, C.; De Henauw, S.; Erhardt, É.; Censi, L.; Manios, Y.; et al. Interaction Effect of the Mediterranean Diet and an Obesity Genetic Risk Score on Adiposity and Metabolic Syndrome in Adolescents: The HELENA Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, J.D.A.; Cureau, F.V.; Ronca, D.B.; Blume, C.A.; Teló, G.H.; Camey, S.A.; de Carvalho, K.M.B.; Schaan, B.D. Association between Diet Quality Index and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Adolescents: Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA). Nutrition 2021, 90, 111216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Avilés, A.; Verstraeten, R.; Lachat, C.; Andrade, S.; Van Camp, J.; Donoso, S.; Kolsteren, P. Dietary Intake Practices Associated with Cardiovascular Risk in Urban and Rural Ecuadorian Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-López, L.; Santiago-Díaz, G.; Nava-Hernández, J.; Muñoz-Torres, A.V.; Medina-Bravo, P.; Torres-Tamayo, M. Mediterranean-Style Diet Reduces Metabolic Syndrome Components in Obese Children and Adolescents with Obesity. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, M.; Sisson, S.B.; Stephens, L.; Morris, A.S.; Aston, C.; Dionne, C.; Knehans, A.; Dickens, R.D. Obesogenic Behaviors and Depressive Symptoms’ Influence on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in American Indian Children. J. Allied Health 2019, 48, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, M.; Fujiwara, A.; Sasaki, S. Added and Free Sugars Intake and Metabolic Biomarkers in Japanese Adolescents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf-Bank, S.; Ahmadi, A.; Paknahad, Z.; Maracy, M.; Nourian, M. Effects of Curcumin on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Obese and Overweight Adolescent Girls: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2019, 137, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macknin, M.; Kong, T.; Weier, A.; Worley, S.; Tang, A.S.; Alkhouri, N.; Golubic, M. Plant-Based No Added Fat or American Heart Association Diets, Impact on Cardiovascular Risk in Obese Hypercholesterolemic Children and Their Parents. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 953–959.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.W.; Tester, J.M.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C. SNAP Participation and Diet-Sensitive Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, S127–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, Y.-I.; Park, H.; Kang, J.-H.; Lee, H.-A.; Song, H.J.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, O.-H. Associations between Sugar Intake from Different Food Sources and Adiposity or Cardio-Metabolic Risk in Childhood and Adolescence: The Korean Child–Adolescent Cohort Study. Nutrients 2015, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Button, A.M.; Tate, C.M.; Kracht, C.L.; Champagne, C.M.; Staiano, A.E. Adolescent Diet Quality, Cardiometabolic Risk, and Adiposity: A Prospective Cohort. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2023, 55, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghetti, E.; Strisciuglio, P.; Spagnolo, A.; Carletti, M.; Paciotti, G.; Muzzi, G.; Beltemacchi, M.; Concolino, D.; Strambi, M.; Rosano, A. Hypertension and Obesity in Italian School Children: The Role of Diet, Lifestyle and Family History. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc Dis. 2015, 25, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, T.; Su, H.; Chen, Y. Dietary and Activity Habits Associated with Hypertension in Kunming School-Aged Children and Adolescents: A Multilevel Analysis of the Study of Hypertension Risks in Children and Adolescents. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 46, 102854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, A.F.G.B.; Vianna, R.P.T.; Lopes, M.T. Association between Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents and Daily Consumption of Soft Drinks: A Brazilian National Study. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Sci. 2022, 35, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voortman, T.; van den Hooven, E.H.; Tielemans, M.J.; Hofman, A.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Franco, O.H. Protein Intake in Early Childhood and Cardiometabolic Health at School Age: The Generation R Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 2117–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers Faijer-Westerink, H.; Stavnsbo, M.; Hutten, B.A.; Chinapaw, M.; Vrijkotte, T.G.M. Ideal Cardiovascular Health at Age 5–6 Years and Cardiometabolic Outcomes in Preadolescence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.Z.; Nguyen, A.N.; Santos, S.; Voortman, T. Diet Quality and Cardiometabolic Health in Childhood: The Generation R Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Farhan, A.K.; Weatherspoon, L.J.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Li, W.; Carlson, J.J. Dietary Quality Evidenced by the Healthy Eating Index and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Kuwaiti Schoolchildren. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perng, W.; Francis, E.C.; Schuldt, C.; Barbosa, G.; Dabelea, D.; Sauder, K.A. Pre- and Perinatal Correlates of Ideal Cardiovascular Health (ICVH) During Early Childhood: A Prospective Analysis in the Healthy Start Study. J. Pediatr. 2021, 234, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodega, P.; Fernández-Alvira, J.M.; Santos-Beneit, G.; de Cos-Gandoy, A.; Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Moreno, L.A.; de Miguel, M.; Carral, V.; Orrit, X.; Carvajal, I.; et al. Dietary Patterns and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Spanish Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the SI! Program for Health Promotion in Secondary Schools. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, M.; Fujiwara, A.; Sasaki, S. Adherence to the Japanese Food Guide: The Association between Three Scoring Systems and Cardiometabolic Risks in Japanese Adolescents. Nutrients 2021, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, R.; Correa-Burrows, P.; Reyes, M.; Blanco, E.; Albala, C.; Gahagan, S. High Cardiometabolic Risk in Healthy Chilean Adolescents: Associations with Anthropometric, Biological and Lifestyle Factors. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostinis-Sobrinho, C.; Abreu, S.; Moreira, C.; Lopes, L.; Garcia-Hermoso, A.; Ramirez-Velez, R.; Correa-Bautista, J.E.; Mota, J.; Santos, R. Muscular Fitness, Adherence to the Southern European Atlantic Diet and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Adolescents. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, J.; Ng, H.M.; Peddie, M.C.; Fleming, E.A.; Webster, K.; Scott, T.; Haszard, J.J. How Does Being Overweight Moderate Associations between Diet and Blood Pressure in Male Adolescents? Nutrients 2021, 13, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, C.J.; Northstone, K. Childhood Dietary Patterns and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Adolescence: Results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) Cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 3369–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krijger, J.A.; Nicolaou, M.; Nguyen, A.N.; Voortman, T.; Hutten, B.A.; Vrijkotte, T.G. Diet Quality at Age 5–6 and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Preadolescents. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 43, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piernas, C.; Wang, D.; Du, S.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Su, C.; Popkin, B.M. Obesity, Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Risk Factors and Dietary Factors among Chinese School-Aged Children. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 25, 826–840. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, A.; Du, S.; Guo, H.; Ma, G. Leading Dietary Determinants Identified Using Machine Learning Techniques and a Healthy Diet Score for Changes in Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Children: A Longitudinal Analysis. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, A.; Ma, G. The Clustering of Low Diet Quality, Low Physical Fitness, and Unhealthy Sleep Pattern and Its Association with Changes in Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Children. Nutrients 2020, 12, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dong, B.; Zou, Z.; Wang, S.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J. Association between Vegetable Consumption and Blood Pressure, Stratified by BMI, among Chinese Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autkar Pusdekar, Y.; Dixit, J.V.; Badhoniya, N. Prevalence and Determinants of Hypertension and Pre-Hypertension among Urban Adolescent School Students of the Age Group 13–17 Years—A Pilot Study. NeuroQuantology 2022, 20, 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Appannah, G.; Pot, G.K.; Huang, R.C.; Oddy, W.H.; Beilin, L.J.; Mori, T.A.; Jebb, S.A.; Ambrosini, G.L. Identification of a Dietary Pattern Associated with Greater Cardiometabolic Risk in Adolescence. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madalosso, M.M.; Martins, N.N.F.; Medeiros, B.M.; Rocha, L.L.; Mendes, L.L.; Schaan, B.D.; Cureau, F.V. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Brazilian Adolescents: Results from ERICA. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 77, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinis-Sobrinho, C.; Santos, R.; Rosário, R.; Moreira, C.; Lopes, L.; Mota, J.; Martinkenas, A.; García-Hermoso, A.; Correa-Bautista, J.E.; Ramírez-Vélez, R. Optimal Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet May Not Overcome the Deleterious Effects of Low Physical Fitness on Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Pooled Analysis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, E.M.; Williams, A.-Y.P.; Abrams, G.A.; Passman, R.S. Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Young Adolescents: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988–2016. South. Med. J. 2021, 114, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckland, G.; Taylor, C.M.; Emmett, P.M.; Johnson, L.; Northstone, K. Prospective Association between a Mediterranean-Style Dietary Score in Childhood and Cardiometabolic Risk in Young Adults from the ALSPAC Birth Cohort. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardini, L.; Croci, M.; Pasqualinotto, L.; Caffetto, K.; Invitti, C. Dietary Habits and Cardiometabolic Health in Obese Children. Obes. Facts 2015, 8, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamian, M.H.; Ebrahimi, H.; Hashemi, H.; Fotouhi, A. Salt Intake and Blood Pressure in Iranian Children and Adolescents: A Population-Based Study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latorre-Millán, M.; Rupérez, A.I.; González-Gil, E.M.; Santaliestra-Pasías, A.; Vázquez-Cobela, R.; Gil-Campos, M.; Aguilera, C.M.; Gil, Á.; Moreno, L.A.; Leis, R.; et al. Dietary Patterns and Their Association with Body Composition and Cardiometabolic Markers in Children and Adolescents: Genobox Cohort. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadas, A.; Rizal, H.; Rajakumar, S.; Mariapun, J.; Yasin, M.S.; Armstrong, M.E.G.; Su, T.T. Dietary Intake, Obesity, and Metabolic Risk Factors among Children and Adolescents in the SEACO-CH20 Cross-Sectional Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; He, T.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Wu, M.; Lin, Z.; Huang, F.; Zhu, Y. Soy Food Intake Associated with Obesity and Hypertension in Children and Adolescents in Guangzhou, Southern China. Nutrients 2022, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljahdali, A.A.; Peterson, K.E.; Cantoral, A.; Ruiz-Narvaez, E.; Tellez-Rojo, M.M.; Kim, H.M.; Hébert, J.R.; Wirth, M.D.; Torres-Olascoaga, L.A.; Shivappa, N.; et al. Diet Quality Scores and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Mexican Children and Adolescents: A Longitudinal Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Cercós, C.; Alacreu, M.; Salar, L.; Moreno Royo, L. Waist-to-Height Ratio and Skipping Breakfast Are Predictive Factors for High Blood Pressure in Adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Khan, M.F.; Bandyopadhyay, K.; Selvaraj, K.; Deshmukh, P. Hypertension and Its Determinants among School Going Adolescents in Selected Urban Slums of Nagpur City, Maharashtra: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 12, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağiran Yilmaz, F.; Çağiran, D.; Özçelik, A.Ö. Adolescent Obesity and Its Association with Diet Quality and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2019, 58, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Howard, A.G.; Herring, A.H.; Thompson, A.L.; Adair, L.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Aiello, A.E.; Zhang, B.; Gordon-Larsen, P. Longitudinal Associations of Away-from-Home Eating, Snacking, Screen Time, and Physical Activity Behaviors with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors among Chinese Children and Their Parents. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toft, U.; Riis, N.L.; Lassen, A.D.; Trolle, E.; Andreasen, A.H.; Frederiksen, A.K.S.; Joergensen, N.R.; Munk, J.K.; Bjoernsbo, K.S. The Effects of Two Intervention Strategies to Reduce the Intake of Salt and the Sodium-To-Potassium Ratio on Cardiovascular Risk Factors. A 4-Month Randomised Controlled Study among Healthy Families. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauber, F.; Campagnolo, P.D.B.; Hoffman, D.J.; Vitolo, M.R. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food Products and Its Effects on Children’s Lipid Profiles: A Longitudinal Study. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc Dis. 2015, 25, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gijssel, R.M.A.; Braun, K.V.E.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Franco, O.H.; Voortman, T. Associations between Dietary Fiber Intake in Infancy and Cardiometabolic Health at School Age: The Generation R Study. Nutrients 2016, 8, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannini, C.; Diesse, L.; D’Adamo, E.; Chiavaroli, V.; de Giorgis, T.; Di Iorio, C.; Chiarelli, F.; Mohn, A. Influence of the Mediterranean Diet on Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Hypercholesterolaemic Children: A 12-Month Intervention Study. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donin, A.S.; Nightingale, C.M.; Owen, C.G.; Rudnicka, A.R.; Cook, D.G.; Whincup, P.H. Takeaway Meal Consumption and Risk Markers for Coronary Heart Disease, Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity in Children Aged 9–10 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arch. Child. 2018, 103, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eloranta, A.M.; Schwab, U.; Venalainen, T.; Kiiskinen, S.; Lakka, H.M.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Lakka, T.A.; Lindi, V. Dietary Quality Indices in Relation to Cardiometabolic Risk among Finnish Children Aged 6–8 years-The PANIC Study. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc. Dis. 2016, 26, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola-Olli, A.V.; Pitkanen, N.; Kettunen, J.; Oikonen, M.K.; Mikkila, V.; Lehtimaki, T.; Kahonen, M.; Pahkala, K.; Niinikoski, H.; Kangas, A.J.; et al. Interactions between Genetic Variants and Dietary Lipid Composition: Effects on Circulating LDL Cholesterol in Children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 1569–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Urrutia, P.; Álvarez-Fariña, R.; Abud, C.; Franco-Trecu, V.; Esparza-Romero, J.; López-Morales, C.M.; Rodríguez-Arellano, M.E.; Valle Leal, J.; Colistro, V.; Granados, J. Effect of Multi-Component School-Based Program on Body Mass Index, Cardiovascular and Diabetes Risks in a Multi-Ethnic Study. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoz-García, N.; Milla-Tobarra, M.; García-Hermoso, A.; Hernández-Luengo, M.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Associations between Dairy Intake, Body Composition, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Spanish Schoolchildren: The Cuenca Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, F.; Martino, E.; Versacci, P.; Niglio, T.; Zanoni, C.; Puddu, P.E. Lifestyle and Awareness of Cholesterol Blood Levels among 29159 Community School Children in Italy. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcel, J.; Béghin, L.; Michels, N.; De Ruyter, T.; Drumez, E.; Cailliau, E.; Polito, A.; Le Donne, C.; Barnaba, L.; Azzini, E.; et al. Nutritional and Physical Fitness Parameters in Adolescence Impact Cardiovascular Health in Adulthood. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Lam, H.S.; Sun, Y.; Kwok, M.K.; Leung, G.M.; Schooling, C.M.; Yeung, S.L.A. Association of Childhood Food Consumption and Dietary Pattern with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Metabolomics in Late Adolescence: Prospective Evidence from “Children of 1997” Birth Cohort. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2024, 78, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtovirta, M.; Matthews, L.A.; Laitinen, T.T.; Nuotio, J.; Niinikoski, H.; Rovio, S.P.; Lagström, H.; Viikari, J.S.A.; Rönnemaa, T.; Jula, A.; et al. Achievement of the Targets of the 20-Year Infancy-Onset Dietary Intervention—Association with Metabolic Profile from Childhood to Adulthood. Nutrients 2021, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, L.C.; Woo, J.G. The Contribution of Dietary Composition over 25 Years to Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Childhood and Adulthood: The Princeton Lipid Research Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 132, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winpenny, E.M.; van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Forouhi, N.G. How Do Short-Term Associations between Diet Quality and Metabolic Risk Vary with Age? Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffeis, C.; Cendon, M.; Tomasselli, F.; Tommasi, M.; Bresadola, I.; Fornari, E.; Morandi, A.; Olivieri, F. Lipid and Saturated Fatty Acids Intake and Cardiovascular Risk Factors of Obese Children and Adolescents. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R.L. Overview of Dietary Assessment Methods for Measuring Intakes of Foods, Beverages, and Dietary Supplements in Research Studies. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 70, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, T.; Goldman, S.; Rollo, M. A Systematic Review of the Validity of Dietary Assessment Methods in Children When Compared with the Method of Doubly Labelled Water. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, J.; Shen, J.; An, R. Artificial Intelligence Applications to Measure Food and Nutrient Intakes: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e54557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, L.M.; Van Emmenis, M.; Nurmi, J.; Kassavou, A.; Sutton, S. Characteristics of Smartphone-Based Dietary Assessment Tools: A Systematic Review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2022, 16, 526–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuparencu, C.; Bulmuş-Tüccar, T.; Stanstrup, J.; La Barbera, G.; Roager, H.M.; Dragsted, L.O. Towards Nutrition with Precision: Unlocking Biomarkers as Dietary Assessment Tools. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 1438–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, L.A.C.; Johnson, L.; Neaves, S.R.; Flach, P.A.; Tilling, K.; Lawlor, D.A. Collecting Food and Drink Intake Data With Voice Input: Development, Usability, and Acceptability Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2023, 11, e41117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekelman, T.A.; Johnson, S.L.; Steinberg, R.I.; Martin, C.K.; Sauder, K.A.; Luckett-Cole, S.; Glueck, D.H.; Hsia, D.S.; Dabelea, D.; Smith, P.B.; et al. A Qualitative Analysis of the Remote Food Photography Method and the Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Dietary Assessment Tool for Assessing Children’s Food Intake Reported by Parent Proxy. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, Y.; Kusama, K.; Sar, K.; Yoshiike, N. Development and Validation of a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) for Assessing Dietary Macronutrients and Calcium Intake in Cambodian School-Aged Children. Nutr. J. 2019, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yuan, K.; Gregg, E.W.; Loustalot, F.; Fang, J.; Hong, Y.; Merritt, R. Trends and Clustering of Cardiovascular Health Metrics Among U.S. Adolescents 1988–2010. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Pu, L.; Zhao, T.; Wang, L.; Shu, C.; Xu, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, R.; Han, L. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Disease from 1990 to 2019 Attributable to Dietary Factors. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charchar, F.J.; Prestes, P.R.; Mills, C.; Ching, S.M.; Neupane, D.; Marques, F.Z.; Sharman, J.E.; Vogt, L.; Burrell, L.M.; Korostovtseva, L.; et al. Lifestyle Management of Hypertension: International Society of Hypertension Position Paper Endorsed by the World Hypertension League and European Society of Hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2024, 42, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database Searched | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| PubMed Central 20 November 2024 | (Diet [Mesh] AND “Cardiovascular Diseases” [Mesh] AND “Risk Factors” [Mesh] AND (Adolescent [Mesh] OR Children [Mesh])) |

| Web of Science 20 December 2024 | ALL = (children OR adolescent) AND ALL = (“cardiovascular diseases”) AND ALL = (diet) AND ALL = (“risk factors”) |

| Embase 20 November 2024 | (‘cardiovascular disease’/exp OR ‘cardiovascular disease’) AND (‘adolescence’/exp OR ‘adolescence’) AND (‘diet’/exp OR ‘diet’) AND (‘risk factors’/exp OR ‘risk factors’) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Butorac, C.; Bruot, V.; Johnson, Z.; Kranz, S. The Relationship Between Children’s Diet and Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2026, 18, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010166

Butorac C, Bruot V, Johnson Z, Kranz S. The Relationship Between Children’s Diet and Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010166

Chicago/Turabian StyleButorac, Claire, Vadin Bruot, Zane Johnson, and Sibylle Kranz. 2026. "The Relationship Between Children’s Diet and Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010166

APA StyleButorac, C., Bruot, V., Johnson, Z., & Kranz, S. (2026). The Relationship Between Children’s Diet and Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients, 18(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010166