Appetite Regulation and Allostatic Load Across Prediabetes Phenotypes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Body Composition

2.3. Cardiorespiratory Fitness

2.4. Metabolic Control

2.5. Appetite Testing

2.6. Food Intake

2.7. Allostatic Load and General Health

2.8. Biochemical Analysis

2.9. Statistics

3. Results

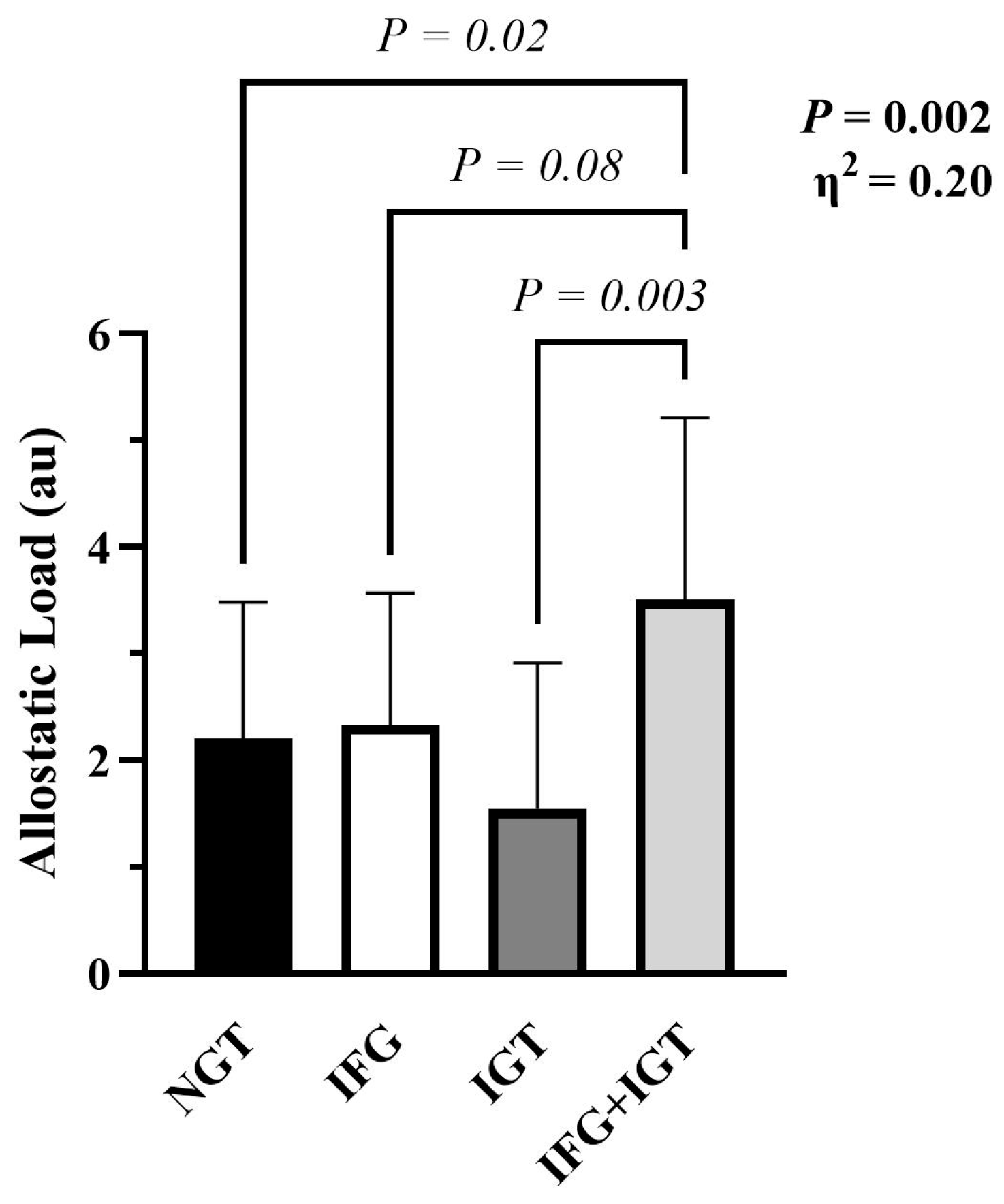

3.1. Participant Characteristics and Allostatic Load

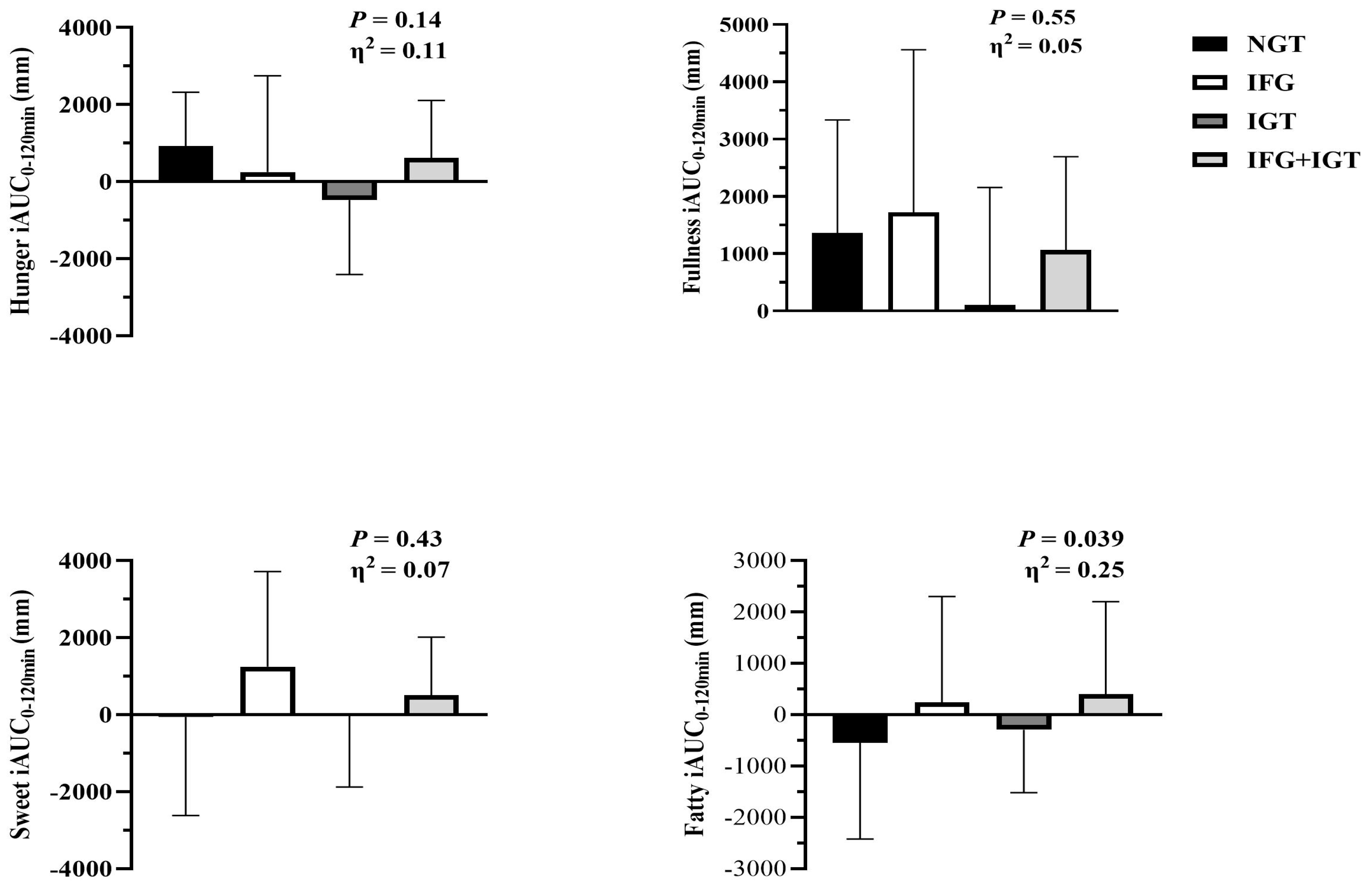

3.2. Appetite Perception and Habitual Dietary Intake

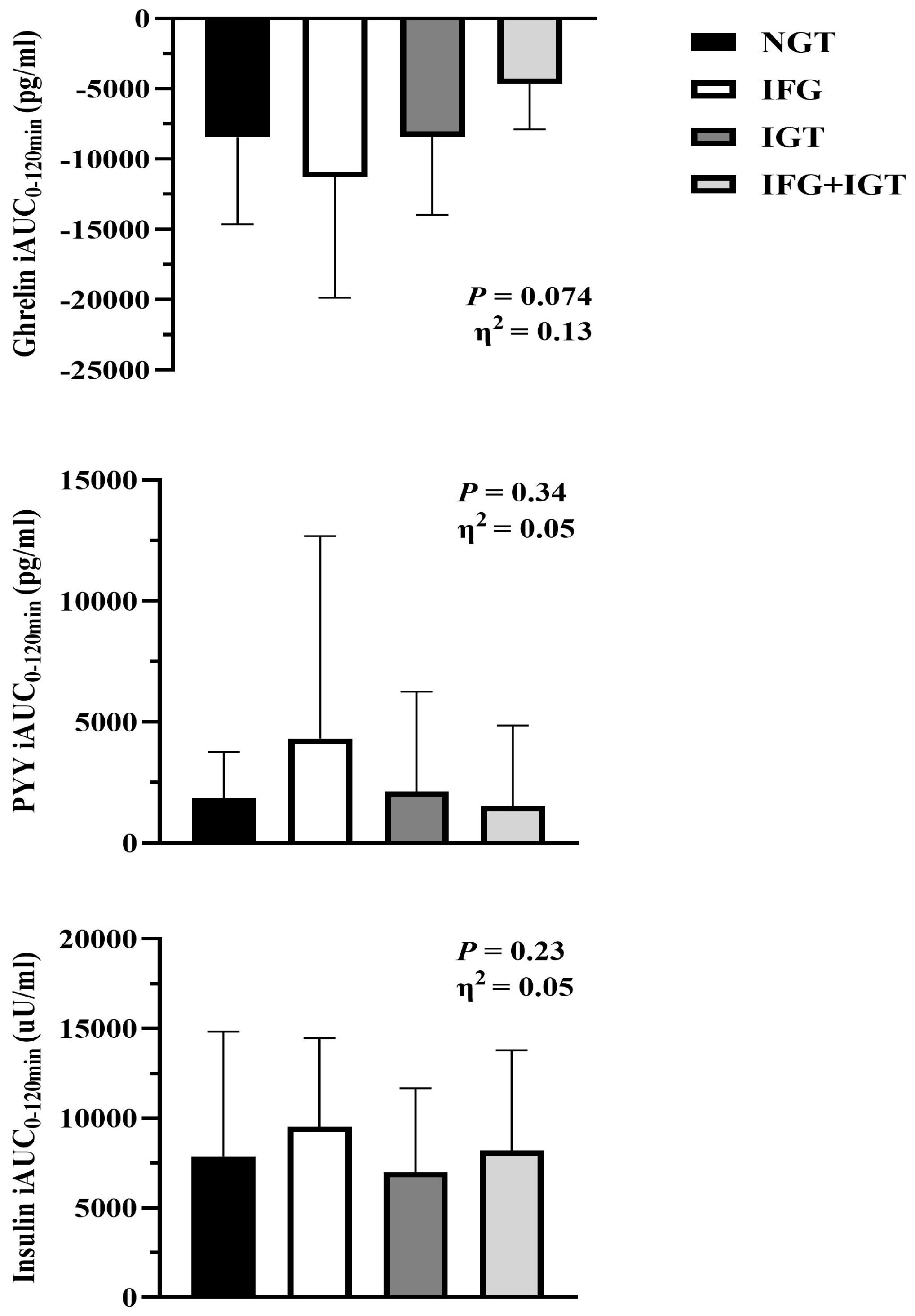

3.3. Glucose and Hormones

3.4. Correlations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CDC National Diabetes Statistics Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Faerch, K.; Borch Johnsen, K.; Holst, J.J.; Vaag, A. Pathophysiology and aetiology of impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance: Does it matter for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes? Diabetologia 2009, 52, 1714–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2024, 48, S27–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.; Abdul Ghani, M. Assessment and treatment of cardiovascular risk in prediabetes: Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 108, 3B–24B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, L.; Bergman, B.; Playdon, M.; Dalla Man, C.; Cobelli, C.; Eckel, R. Impaired fasting glucose with or without impaired glucose tolerance: Progressive or parallel states of prediabetes? Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 295, E428–E435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, L.; Kahn, S.; Christophi, C.; Knowler, W.; Hamman, R. Regression from pre-diabetes to normal glucose regulation in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1583–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.R.; Everett, B.M.; Birtcher, K.K.; Brown, J.M.; Januzzi, J.L.J.; Kalyani, R.R.; Kosiborod, M.; Magwire, M.; Morris, P.B.; Neumiller, J.J.; et al. 2020 Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Novel Therapies for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1117–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Bowles, N.P.; Gray, J.D.; Hill, M.N.; Hunter, R.G.; Karatsoreos, I.N.; Nasca, C. Mechanisms of stress in the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1353–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, T.E.; McEwen, B.S.; Rowe, J.W.; Singer, B.H. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4770–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foss, B.; Dyrstad, S.M. Stress in obesity: Cause or consequence? Med. Hypotheses 2011, 77, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemot-Legris, O.; Muccioli, G.G. Obesity-Induced Neuroinflammation: Beyond the Hypothalamus. Trends Neurosci. 2017, 40, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanon, N.; Lasselin, J.; Capuron, L. Neuropsychiatric comorbidity in obesity: Role of inflammatory processes. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenard, N.R.; Berthoud, H. Central and peripheral regulation of food intake and physical activity: Pathways and genes. Obesity 2008, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faerch, K.; Vaag, A.; Holst, J.J.; Glmer, C.; Pedersen, O.; Borch Johnsen, K. Impaired fasting glycaemia vs impaired glucose tolerance: Similar impairment of pancreatic alpha and beta cell function but differential roles of incretin hormones and insulin action. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, S.K.; Liu, Z.; Barrett, E.J.; Weltman, A. Exercise resistance across the prediabetes phenotypes: Impact on insulin sensitivity and substrate metabolism. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2016, 17, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.; Dalla Man, C.; Campioni, M.; Chittilapilly, E.; Basu, R.; Toffolo, G.; Cobelli, C.; Rizza, R. Pathogenesis of pre-diabetes: Mechanisms of fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia in people with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes 2006, 55, 3536–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, S.K.; Remchak, M.E.; Heiston, E.M.; Battillo, D.J.; Gow, A.J.; Shah, A.M.; Liu, Z. Intermediate versus morning chronotype has lower vascular insulin sensitivity in adults with obesity. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 1582–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, S.K.; Heiston, E.M.; Battillo, D.J.; Ragland, T.J.; Gow, A.J.; Shapses, S.A.; Shah, A.M.; Patrie, J.T.; Barrett, E.J. Metformin Blunts Vascular Insulin Sensitivity After Exercise Training in Adults at Risk for Metabolic Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, dgaf551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiston, E.M.; Liu, Z.; Ballantyne, A.; Kranz, S.; Malin, S.K. A single bout of exercise improves vascular insulin sensitivity in adults with obesity. Obesity 2021, 29, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiston, E.M.; Eichner, N.Z.M.; Gilbertson, N.M.; Gaitán, J.M.; Kranz, S.; Weltman, A.; Malin, S.K. Two weeks of exercise training intensity on appetite regulation in obese adults with prediabetes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 126, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainisch, B.K.W.; Upchurch, D.M. Sociodemographic Correlates of Allostatic Load Among a National Sample of Adolescents: Findings From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2008. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquali, R. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sex hormones in chronic stress and obesity: Pathophysiological and clinical aspects. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1264, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.J.; Nowson, C.A. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition 2007, 23, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.P.; He, Y.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Ding, L.; Ayanian, J.Z. Psychosocial stress and change in weight among US adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, T.W.; Fray, P.J. Stress-induced eating: Fact, fiction or misunderstanding? Appetite 1980, 1, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, G.; Wardle, J.; Gibson, E.L. Stress and food choice: A laboratory study. Psychosom. Med. 2000, 62, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.A.; Loaiza, S.; Gonzalez, Z.; Pita, J.; Morales, J.; Pecora, D.; Wolf, A. Food selection changes under stress. Physiol. Behav. 2006, 87, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutters, F.; Nieuwenhuizen, A.G.; Lemmens, S.G.T.; Born, J.M.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Acute stress-related changes in eating in the absence of hunger. Obesity 2009, 17, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemmens, S.G.; Rutters, F.; Born, J.M.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Stress augments food ‘wanting’ and energy intake in visceral overweight subjects in the absence of hunger. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 103, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Sinha, R.; Lacadie, C.; Small, D.M.; Sherwin, R.S.; Potenza, M.N. Neural correlates of stress- and food cue-induced food craving in obesity: Association with insulin levels. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T.C.; Epel, E.S. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 91, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzoub, J.A. Corticotropin-releasing hormone physiologyThis paper was presented at the 4th Ferring Pharmaceuticals International Paediatric Endocrinology Symposium, Paris (2006). Ferring Pharmaceuticals has supported the publication of these proceedings. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 155, S71–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallman, M.F.; Pecoraro, N.C.; la Fleur, S.E. Chronic stress and comfort foods: Self-medication and abdominal obesity. Brain Behav. Immun. 2005, 19, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.R.; Hu, F.B. Short sleep duration and weight gain: A systematic review. Obesity 2008, 16, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Prigeon, R.; Davis, H.; Bidlingmaier, M.; Kahn, S.; Cummings, D.; Tschöp, M.H.; D’Alessio, D. Ghrelin suppresses glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and deteriorates glucose tolerance in healthy humans. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2145–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, S.K.; Kirwan, J.P. Fasting hyperglycaemia blunts the reversal of impaired glucose tolerance after exercise training in obese older adults. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012, 14, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, S.K.; Haus, J.M.; Solomon, T.P.; Blaszczak, A.; Kashyap, S.R.; Kirwan, J.P. Insulin sensitivity and metabolic flexibility following exercise training among different obese insulin resistant phenotypes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 305, E1292–E1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, N.M. Glucose Tolerance is Linked to Postprandial Fuel Use Independent of Exercise Dose. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 2058–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallman, M.F. Stress-induced obesity and the emotional nervous system. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Wansink, B.; Jeffrey Inman, J. The Influence of Incidental Affect on Consumers’ Food Intake. J. Market 2007, 71, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloğlu, U.S.; Erol, K. Fatigue, anxiety and depression in patients with prediabetes: A controlled cross-sectional study. Diabetol. Int. 2022, 13, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, K.L.; Van Cauter, E. Associations between sleep loss and increased risk of obesity and diabetes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1129, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, S.; Lin, L.; Austin, D.; Young, T.; Mignot, E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004, 1, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüssler, P.; Uhr, M.; Ising, M.; Weikel, J.C.; Schmid, D.A.; Held, K.; Mathias, S.; Steiger, A. Nocturnal ghrelin, ACTH, GH and cortisol secretion after sleep deprivation in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Stone, W.S.; Huang, L.; Zhuang, J.; He, B.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y. Effects of sleep restriction periods on serum cortisol levels in healthy men. Brain Res. Bull. 2008, 77, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, K.; Blundell, J. The Psychobiology of Hunger—A Scientific Perspective. Topoi 2021, 40, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.B.; Wynne, J.L.; Ehlert, A.M.; Mowfy, Z. Life stress and background anxiety are not associated with resting metabolic rate in healthy adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 812–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.A.; Green, B.P.; James, L.J.; Stevenson, E.J.; Rumbold, P.L.S. The Effect of a Dairy-Based Recovery Beverage on Post-Exercise Appetite and Energy Intake in Active Females. Nutrients 2016, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, A.M.W.; McLaughlin, J.; Gilmore, W.; Maughan, R.J.; Evans, G.H. The Acute Effects of Simple Sugar Ingestion on Appetite, Gut-Derived Hormone Response, and Metabolic Markers in Men. Nutrients 2017, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, M.T.; Bingham, B.A.; Aldana, P.C.; Chung, S.T.; Sumner, A.E. Variation in the Calculation of Allostatic Load Score: 21 Examples from NHANES. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, 4, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NGT | IFG | IGT | IFG + IGT | p | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 28 | 20 | 18 | 32 | ||

| F/M | 23/5 | 14/6 | 16/2 | 24/8 | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (y) | 52.9 ± 7.6 | 56.6 ± 6.3 | 55.4 ± 8.4 | 57.0 ± 7.4 | 0.17 | 0.05 |

| VO2max (mL/kg/min) * | 21.9 ± 4.5 | 23.9 ± 4.2 | 22.1 ± 3.0 | 22.2 ± 5.3 | 0.38 | 0.03 |

| ATP III Criteria | 3.07 ± 0.86 | 3.45 ± 0.83 | 2.72 ± 0.75 | 3.59 ± 0.76 | 0.002 | 0.15 |

| Weight (kg) * | 101 ± 21.4 | 99.8 ± 17.1 | 88.8 ± 18.3 | 105 ± 21.7 ^ | 0.037 | 0.09 |

| Body Fat (%) | 44.9 ± 5.28 | 43.8 ± 5.71 | 44.7 ± 5.51 | 44.2 ± 6.55 | 0.93 | <0.01 |

| Lean Mass (kg) | 51.7 ± 11.4 | 53.5 ± 9.36 | 45.3 ± 8.11 | 54.7 ± 10.7 ^ | 0.023 | 0.12 |

| RMR (kcal/d) | 1402 ± 193 | 1366 ± 426 | 1434 ± 250 | 1426 ± 262 | 0.53 | 0.03 |

| RMR (kcal/kg/d) | 14.4 ± 3.12 | 14.3 ± 2.87 | 16.7 ± 3.57 | 13.9 ± 2.78 ^ | 0.049 | 0.09 |

| AL Parameters | ||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 132 ± 14.2 | 129 ± 10.7 | 129 ± 7.94 | 133 ± 14.7 | 0.59 | 0.02 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80.1 ± 9.91 | 78.2 ± 8.76 | 80.7 ± 6.30 | 79.8 ± 9.01 | 0.84 | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) * | 35.2 ± 5.4 | 34.8 ± 4.4 | 32.6 ± 5.7 | 36.5 ± 5.7 | 0.079 | 0.07 |

| WC (cm) * | 110 ± 14.3 | 112 ± 13.4 | 102 ± 11.9 | 114 ± 11.7 ^ | 0.022 | 0.10 |

| HDL (mg/dL) * | 51.0 ± 11.6 | 49.0 ± 10.3 | 52.1 ± 14.7 | 46.9 ± 10.3 | 0.43 | 0.03 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 212 ± 46.9 | 210 ± 31.1 | 187 ± 48.5 | 201 ± 37.8 | 0.23 | 0.04 |

| hsCRP * | 5.52 ± 5.16 | 3.92 ± 3.80 | 3.35 ± 3.69 | 6.18 ± 6.39 | 0.18 | 0.07 |

| HbA1c (%) * | 5.36 ± 0.23 | 5.57 ± 0.31 | 5.57 ± 0.36 | 5.98 ± 0.48 †‡^ | <0.001 | 0.32 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.32 ± 0.29 | 4.37 ± 0.34 | 4.36 ± 0.29 | 4.22 ± 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| OGTT | ||||||

| Fasting Glc (mg/dL) * | 92.9 ± 7.2 | 108 ± 6.9†^ | 90.0 ± 5.7 | 117 ± 13.0 †‡^ | <0.001 | 0.63 |

| 120 min Glc (mg/dL) * | 114 ± 13.4 | 116 ± 15.1 | 164 ± 17.6 †‡ | 177 ± 28.0 †‡ | <0.001 | 0.71 |

| Glc iAUC0–120min (mg/dL) * | 4650 ± 1807 | 4394 ± 1827 | 7981 ± 2156 †‡ | 8044 ± 2497 †‡ | <0.001 | 0.39 |

| Fasting Insulin (μU/mL) * | 10.7 ± 6.08 | 14.0 ± 9.24 | 9.49 ± 5.28 | 17.6 ± 11.1 †^ | 0.013 | 0.12 |

| 120 min Insulin (μU/mL) * | 61.8 ± 56.9 | 74.0 ± 41.8 | 97.3 ± 109 | 150 ± 155 †‡ | <0.001 | 0.19 |

| SIIS (au) * | 0.30 ± 0.13 | 0.30 ± 0.13 | 0.31 ± 0.13 | 0.30 ± 0.14 | 0.98 | <0.01 |

| HOMA-IR (au) * | 2.53 ± 1.5 | 3.74 ± 2.6 | 2.14 ± 1.2 | 5.21 ± 3.5 †^ | <0.001 | 0.21 |

| NGT | IFG | IGT | IFG + IGT | p | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Health | ||||||

| General Health (au) | 61.6 ± 16.1 | 66.8 ± 19.5 | 66.1 ± 19.3 | 58.4 ± 22.6 | 0.55 | 0.03 |

| Energy and Fatigue (au) | 45.6 ± 14.6 | 55.6 ± 18.7 | 57.5 ± 14.8 | 45.2 ± 24.4 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Emotional Well-Being (au) | 74.7 ± 9.3 | 75.8 ± 16.5 | 74.7 ± 16.8 | 79.0 ± 15.3 | 0.76 | 0.02 |

| Physical Function | 81.4 ± 15.1 | 82.8 ± 15.3 | 84.6 ± 16.0 | 79.5 ± 15.0 | 0.81 | 0.01 |

| Sleeping Habits | ||||||

| PSQI (au) | 7.58 ± 3.02 | 6.47 ± 3.45 | 6.57 ± 3.41 | 6.05 ± 3.36 | 0.52 | 0.03 |

| Epworth (au) | 5.56 ± 4.16 | 5.25 ± 3.63 | 5.47 ± 4.06 | 7.52 ± 4.92 | 0.19 | 0.05 |

| NGT | IFG | IGT | IFG + IGT | p | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting Appetite | ||||||

| Hunger (mm) | 31.6 ± 21.5 | 35.9 ± 26.0 | 38.3 ± 25.7 | 36.6 ± 26.1 | 0.84 | 0.01 |

| Fullness (mm) | 23.1 ± 19.5 | 19.3 ± 23.2 | 35.9 ± 31.4 | 24.1 ± 25.2 | 0.99 | <0.01 |

| Sweet (mm) | 64.7 ± 27.7 | 67.9 ± 26.3 | 64.2 ± 26.3 | 69.8 ± 28.5 | 0.96 | <0.01 |

| Fatty (mm) | 60.0 ± 28.3 | 59.9 ± 25.6 | 66.9 ± 24.0 | 55.9 ± 31.5 | 0.55 | 0.03 |

| Fasting Hormones | ||||||

| Leptin (ng/mL) * | 50.1 ± 21.9 | 42.4 ± 24.7 | 43.6 ± 30.8 | 53.4 ± 31.3 | 0.70 | 0.02 |

| Ghrelin (pg/mL) * | 190 ± 106 | 203 ± 137 | 180 ± 90.3 | 112 ± 67.3 † | 0.013 | 0.15 |

| PYY (pg/mL) * | 105 ± 71.7 | 101 ± 52.5 | 75.1 ± 41.4 | 106 ± 56.7 | 0.61 | 0.02 |

| Food Intake | ||||||

| Total (kcals) | 1901 ± 396 | 1975 ± 556 | 2057 ± 686 | 1948 ± 504 | 0.93 | <0.01 |

| Fat (g) | 88.8 ± 30.4 | 86.7 ± 36.2 | 85.5 ± 28.1 | 80.9 ± 30.1 | 0.91 | <0.01 |

| CHO (g) | 193 ± 40.4 | 201 ± 78.0 | 238 ± 40.4 | 212 ± 65.6 | 0.53 | 0.04 |

| Soluble Fiber (g) | 0.96 ± 0.98 | 1.24 ±0.85 | 0.64 ± 0.79 | 0.81 ± 0.71 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Protein (g) | 82.3 ± 16.3 | 90.7 ± 32.6 | 86.8 ± 26.8 | 91.7 ± 46.7 | 0.98 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Malin, S.K.; Heiston, E.M. Appetite Regulation and Allostatic Load Across Prediabetes Phenotypes. Nutrients 2026, 18, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010158

Malin SK, Heiston EM. Appetite Regulation and Allostatic Load Across Prediabetes Phenotypes. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010158

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalin, Steven K., and Emily M. Heiston. 2026. "Appetite Regulation and Allostatic Load Across Prediabetes Phenotypes" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010158

APA StyleMalin, S. K., & Heiston, E. M. (2026). Appetite Regulation and Allostatic Load Across Prediabetes Phenotypes. Nutrients, 18(1), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010158