Hops (Humulus lupulus) Extract Enhances Redox Resilience and Attenuates Quinolinic Acid-Induced Excitotoxic Damage in the Brain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Chemical Combinatory Assays

2.2.1. Superoxide Anion (O2•−) Scavenging Assay

2.2.2. Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) Scavenging Assay

2.2.3. Peroxynitrite (ONOO−) Scavenging Assay

2.2.4. Oxidative Protein Degradation Assay

2.2.5. Oxidative DNA Degradation Assay

2.3. Animals

2.4. Hops Extract Administration

2.5. Lipid Peroxidation

2.6. GSH/GSSG Ratio

2.7. Glutathione Reductase (GR) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) Activity

2.8. Catalase Activity

2.9. Determination of Protein Concentration

2.10. Reverse Transcription (RT) and Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

2.11. Quinolinic Acid Intrastriatal Administration and Circling Behavior

2.12. Apoptosis Determination

2.13. Cell Fractionation

2.14. Western Blot

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

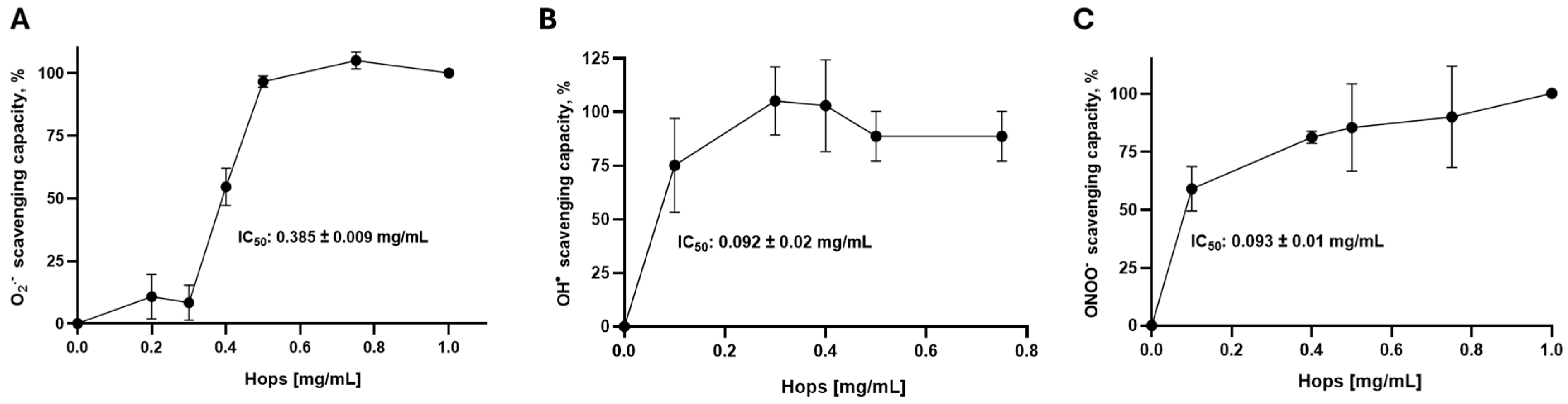

3.1. Hops Extract Acts as a Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Scavenger on Combinatorial Chemistry Assays

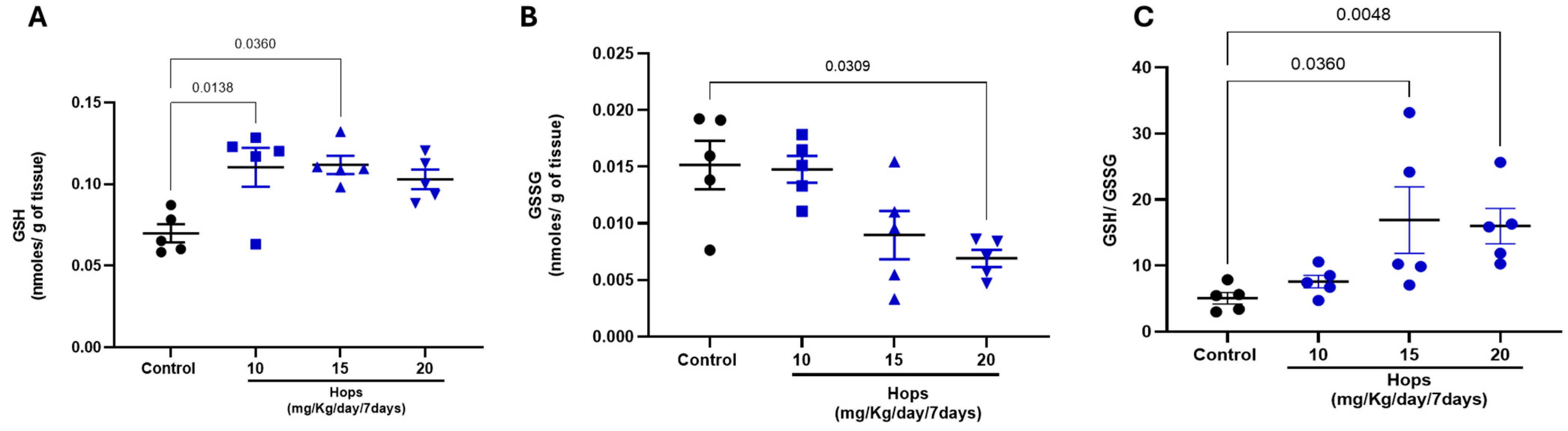

3.2. Effect of Subchronic Administration of Hops Extract on Brain Glutathione Status

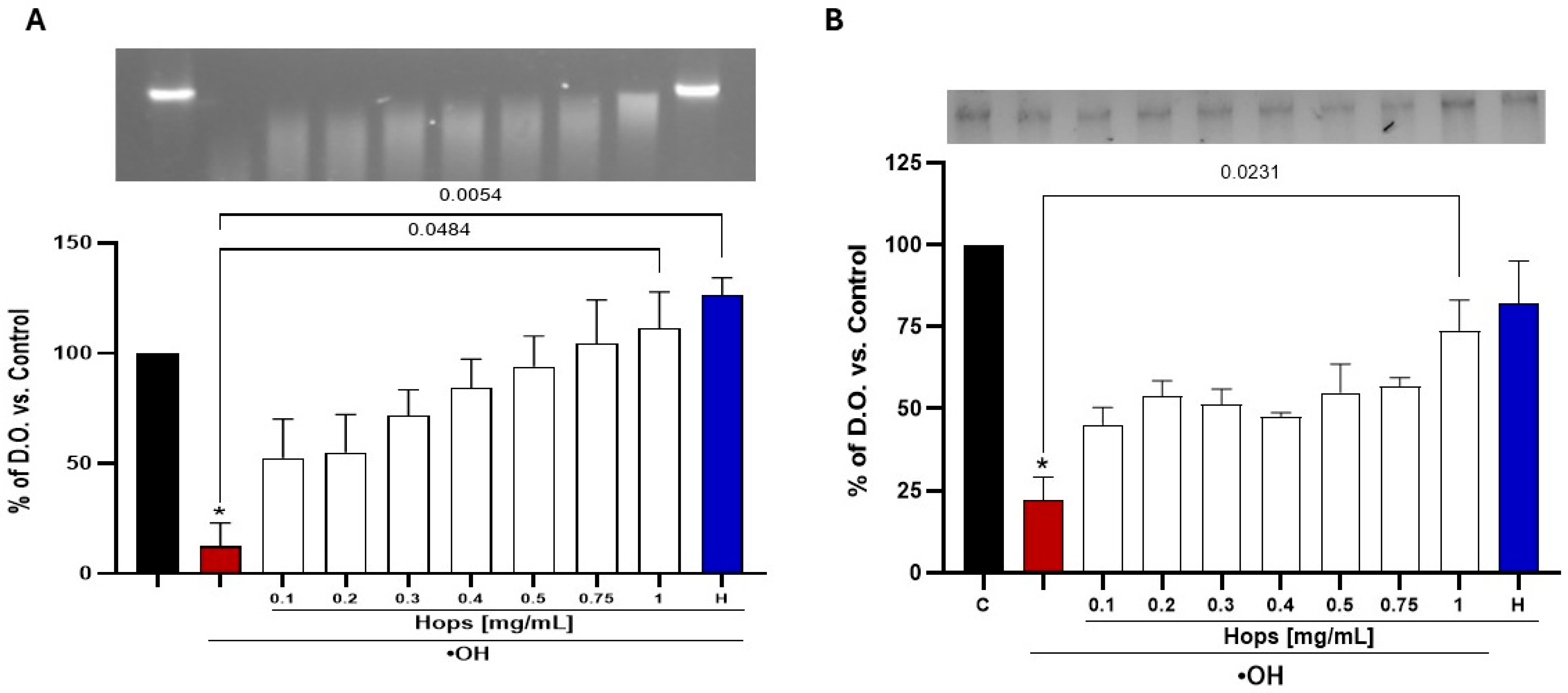

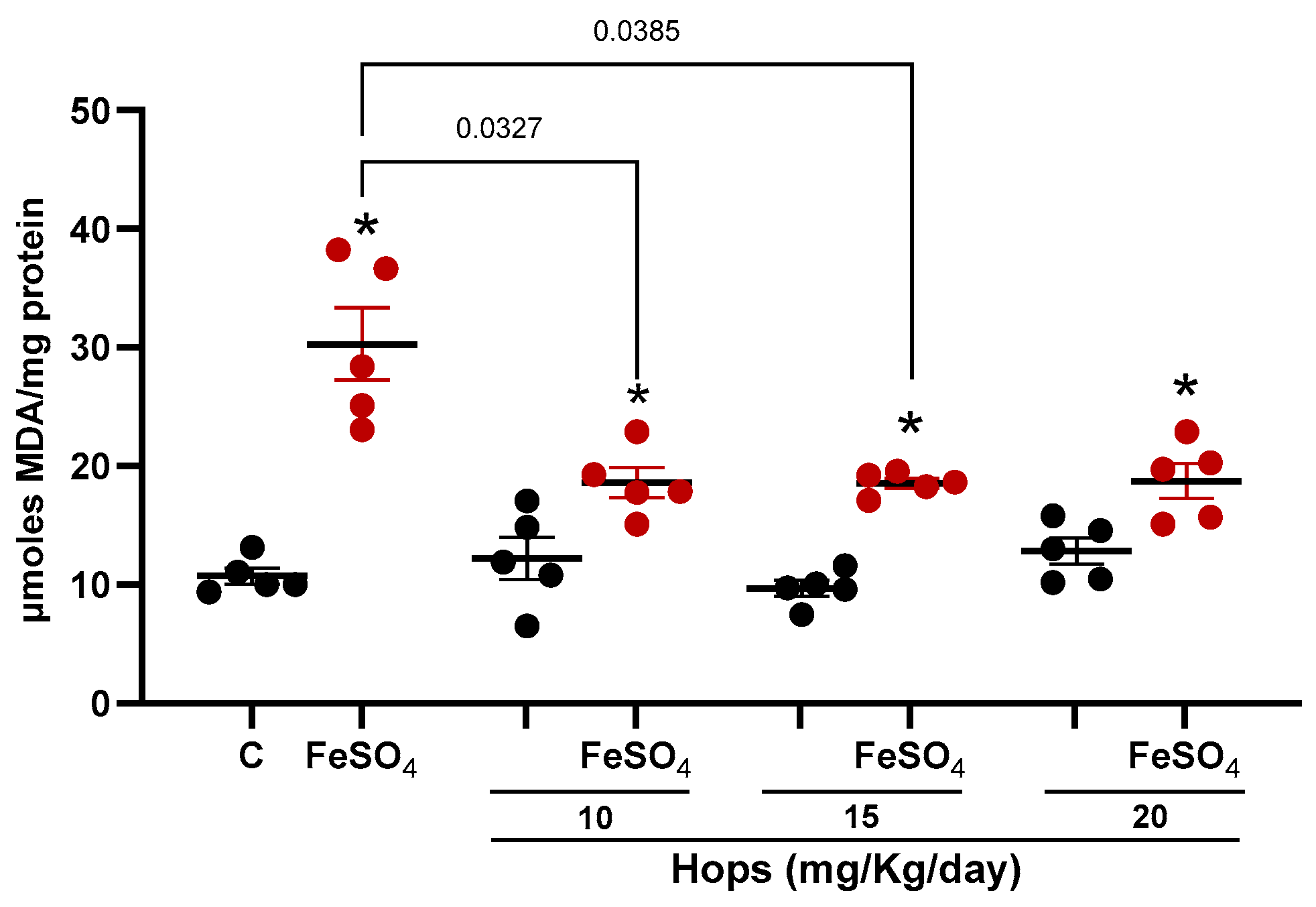

3.3. Ex Vivo Pro-Oxidant Challenge Following Hops Extract Administration

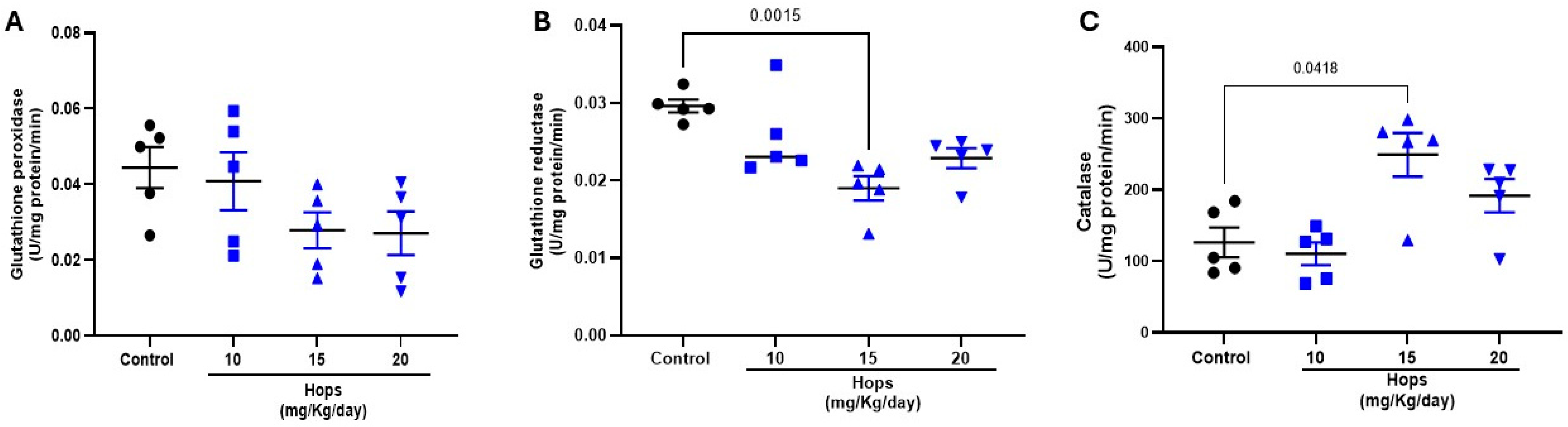

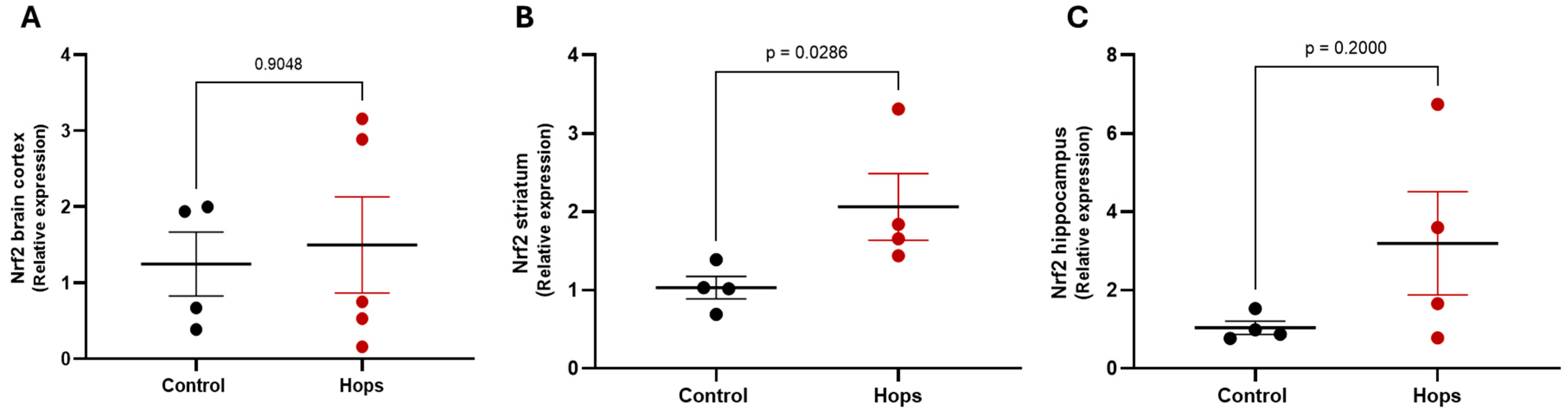

3.4. Hops Extract Administration Promotes an Antioxidant Environment and Modulates Nrf2 Expression in Brain Regions

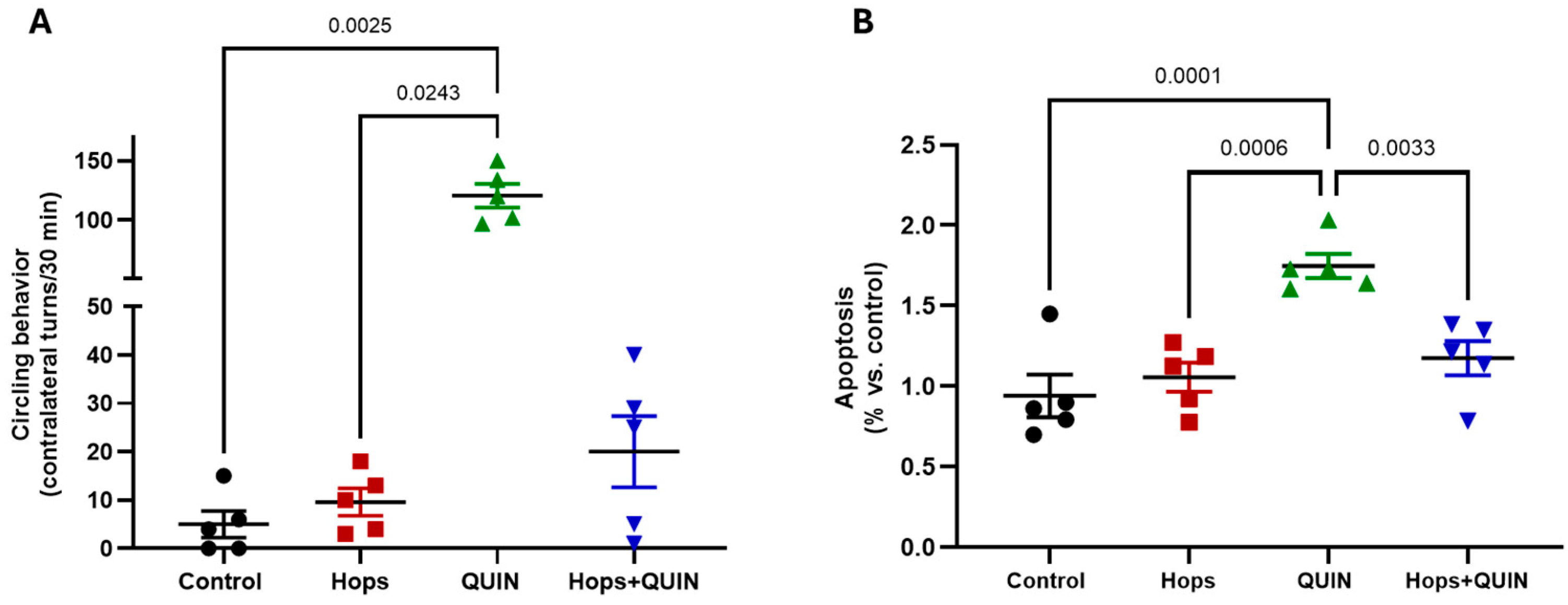

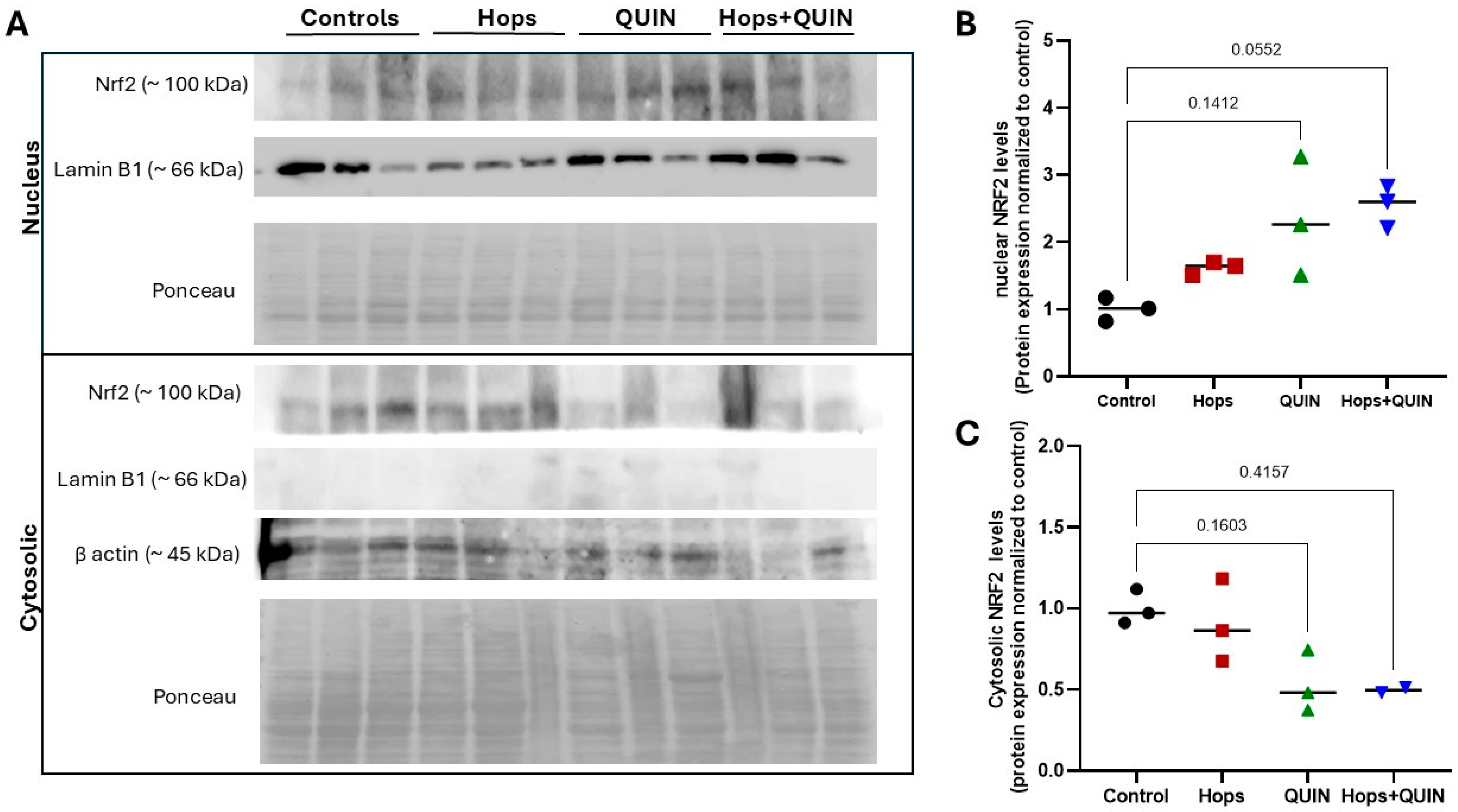

3.5. Effects of Hops Extract on Quinolinic Acid-Induced Excitotoxicity and Apoptosis in the Striatum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ●OH | Hydroxyl radical |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| CaCl2 | Calcium chloride |

| cDNAs | Complementary DNAs |

| CuSO4 | Copper (II) sulfate |

| DCF | Dichlorofluorescein |

| DCFH-DA | Dichlorofluorescein diacetate |

| DFO | Deferoxamine |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DTPA | Diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid |

| DTT | Dithiothreitol |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| FeCl3 | Ferric chloride |

| FeSO4 | Ferrous sulfate |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| Hops | Humulus lupulus |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| NBT | Nitroblue tetrazolium |

| NEM | N-ethylmaleimide |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor |

| O2●− | Superoxide anion |

| ONOO− | Peroxynitrite |

| OPA | O-pthaldehyde |

| QUIN | Quinolinic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

References

- Aghamiri, V.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Nazemiyeh, H. The effect of Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) on early menopausal symptoms and hot flashes: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2016, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoli, P.; Zavatti, M. Pharmacognostic and pharmacological profile of Humulus lupulus L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnick, C.R. Pharmacopoeial Standards of Herbal Plants; Sri Satguru Publications: Delhi, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Van Cleemput, M.; Cattoor, K.; De Bosscher, K.; Haegeman, G.; De Keukeleire, D.; Heyerick, A. Hop (Humulus lupulus)-derived bitter acids as multipotent bioactive compounds. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turdo, A.; Glaviano, A.; Pepe, G.; Calapa, F.; Raimondo, S.; Fiori, M.E.; Carbone, D.; Basilicata, M.G.; Di Sarno, V.; Ostacolo, C.; et al. Nobiletin and Xanthohumol Sensitize Colorectal Cancer Stem Cells to Standard Chemotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.F.; Liu, Y.P.; Liao, J.Z.; Gan, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, R.R.; Wang, F.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, L. Xanthohumol Promotes Skp2 Ubiquitination Leading to the Inhibition of Glycolysis and Tumorigenesis in Ovarian Cancer. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2024, 52, 865–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.J.; Lin, J.K. Mechanisms of cancer chemoprevention by hop bitter acids (beer aroma) through induction of apoptosis mediated by Fas and caspase cascades. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saugspier, M.; Dorn, C.; Czech, B.; Gehrig, M.; Heilmann, J.; Hellerbrand, C. Hop bitter acids inhibit tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 28, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrao, R.; Duarte, D.; Costa, R.; Soares, R. Isoxanthohumol modulates angiogenesis and inflammation via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, tumor necrosis factor alpha and nuclear factor kappa B pathways. Biofactors 2013, 39, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwe, A.; Rudolph, K.; Anke, T.; Erkel, G. Inhibition of TGF-beta signaling, vasculogenic mimicry and proinflammatory gene expression by isoxanthohumol. Investig. New Drugs 2012, 30, 898–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rancan, L.; Paredes, S.D.; Garcia, I.; Munoz, P.; Garcia, C.; Lopez de Hontanar, G.; de la Fuente, M.; Vara, E.; Tresguerres, J.A.F. Protective effect of xanthohumol against age-related brain damage. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 49, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulikova, K.; Karabin, M.; Nespor, J.; Dostalek, P. Therapeutic Perspectives of 8-Prenylnaringenin, a Potent Phytoestrogen from Hops. Molecules 2018, 23, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartmanska, A.; Walecka-Zacharska, E.; Tronina, T.; Poplonski, J.; Sordon, S.; Brzezowska, E.; Bania, J.; Huszcza, E. Antimicrobial Properties of Spent Hops Extracts, Flavonoids Isolated Therefrom, and Their Derivatives. Molecules 2018, 23, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleha, R.; Radochova, V.; Mikyska, A.; Houska, M.; Bolehovska, R.; Janovska, S.; Pejchal, J.; Muckova, L.; Cermak, P.; Bostik, P. Strong Antimicrobial Effects of Xanthohumol and Beta-Acids from Hops against Clostridioides difficile Infection In Vivo. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zhang, B.; Ge, C.; Peng, S.; Fang, J. Xanthohumol, a polyphenol chalcone present in hops, activating Nrf2 enzymes to confer protection against oxidative damage in PC12 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.S.; Lim, J.; Gal, J.; Kang, J.C.; Kim, H.J.; Kang, B.Y.; Choi, H.J. Anti-inflammatory activity of xanthohumol involves heme oxygenase-1 induction via NRF2-ARE signaling in microglial BV2 cells. Neurochem. Int. 2011, 58, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Deeb, D.; Liu, Y.; Gautam, S.; Dulchavsky, S.A.; Gautam, S.C. Immunomodulatory activity of xanthohumol: Inhibition of T cell proliferation, cell-mediated cytotoxicity and Th1 cytokine production through suppression of NF-kappaB. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2009, 31, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ho, S.L.; Poon, C.Y.; Yan, T.; Li, H.W.; Wong, M.S. Amyloid-beta Aggregation Inhibitory and Neuroprotective Effects of Xanthohumol and its Derivatives for Alzheimer’s Diseases. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2019, 16, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Yang, C.; Lin, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J. Preventive effects of xanthohumol in APP/PS1 mice based on multi-omics atlas. Brain Res. Bull. 2025, 224, 111316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, C.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J. Protective signature of xanthohumol on cognitive function of APP/PS1 mice: A urine metabolomics approach by age. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1423060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor, S.L.; Teoh, S.L.; Lim, W.L. Plant Polyphenols as Neuroprotective Agents in Parkinson’s Disease Targeting Oxidative Stress. Curr. Drug Targets 2020, 21, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Khandale, N.; Birla, D.; Bashir, B.; Vishwas, S.; Kulkarni, M.P.; Rajput, R.P.; Pandey, N.K.; Loebenberg, R.; Davies, N.M.; et al. Formulation and optimization of xanthohumol loaded solid dispersion for effective treatment of Parkinson’s disease in rats: In vitro and in vivo assessment. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 102, 106385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.F.; Daglia, M.; D’Antona, G.; Sobarzo-Sanchez, E.; Talas, Z.S.; Nabavi, S.M. Natural compounds used as therapies targeting to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2015, 16, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagashira, M.; Watanabe, M.; Uemitsu, N. Antioxidative activity of hop bitter acids and their analogues. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1995, 59, 740–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, N.; Li, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, C.; Lin, B.; Hou, Y. Characteristic alpha-Acid Derivatives from Humulus lupulus with Antineuroinflammatory Activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 3081–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.V.d.A.; Arend, G.D.; Zielinski, A.A.F.; Di Luccio, M.; Ambrosi, A. Xanthohumol properties and strategies for extraction from hops and brewery residues: A review. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.H.; Fu, M.L.; Chen, M.M.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.J.; He, G.Q.; Pu, S.C. Preparative isolation and purification of xanthohumol from hops (Humulus lupulus L.) by high-speed counter-current chromatography. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biendl, M. Isolation of Prenylflavonoids From Hops. Acta Hortic. 2013, 1010, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floriano-Sanchez, E.; Villanueva, C.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Rocha, D.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, D.J.; Cardenas-Rodriguez, N.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid is a potent in vitro scavenger of peroxynitrite, singlet oxygen, hydroxyl radical, superoxide anion and hypochlorous acid and prevents in vivo ozone-induced tyrosine nitration in lungs. Free Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.; Aruoma, O.I. The deoxyribose method: A simple “test-tube” assay for determination of rate constants for reactions of hydroxyl radicals. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 165, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, J.S.; Chen, J.; Ischiropoulos, H.; Crow, J.P. Oxidative chemistry of peroxynitrite. Methods Enzymol. 1994, 233, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocha, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Ohtaki, H.; Fukuda, T.; Aoyagi, T. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated degradation of protein: Different oxidation modes of copper- and iron-dependent hydroxyl radicals on the degradation of albumin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1337, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorcas Aremu, T.; Ramirez Ortega, D.; Blanco Ayala, T.; Gonzalez Esquivel, D.F.; Pineda, B.; Perez de la Cruz, G.; Salazar, A.; Flores, I.; Meza-Sosa, K.F.; Sanchez Chapul, L.; et al. Modulation of Brain Kynurenic Acid by N-Acetylcysteine Prevents Cognitive Impairment and Muscular Weakness Induced by Cisplatin in Female Rats. Cells 2024, 13, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, L.F.; Martins, J.D.; Cavallaro, C.H.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Oliveira, P.J.; Pereira, S.P. Development of a 96-well based assay for kinetic determination of catalase enzymatic-activity in biological samples. Toxicol. Vitr. 2020, 69, 104996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, M.; Sebai, H.; Gadacha, W.; Boughattas, N.A.; Reinberg, A.; Mossadok, B.A. Catalase activity and rhythmic patterns in mouse brain, kidney and liver. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 145, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aremu, T.D.; Blanco Ayala, T.; Meza-Sosa, K.F.; Ramírez Ortega, D.; González Esquivel, D.F.; Vázquez Cervantes, G.I.; Flores, I.; González Alfonso, W.L.; Custodio Ramírez, V.; Salazar, A.; et al. N-Acetylcysteine Prevents Skeletal Muscle Cisplatin-Induced Atrophy by Inducing Myogenic microRNAs and Maintaining the Redox Balance. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-De La Cruz, V.; Gonzalez-Cortes, C.; Galvan-Arzate, S.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Perez-Severiano, F.; Ali, S.F.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Santamaria, A. Excitotoxic brain damage involves early peroxynitrite formation in a model of Huntington’s disease in rats: Protective role of iron porphyrinate 5,10,15,20-tetrakis (4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrinate iron (III). Neuroscience 2005, 135, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, A.; Munoz, M.F.; Arguelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: Production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardillo-Diaz, R.; Perez-Garcia, P.; Castro, C.; Nunez-Abades, P.; Carrascal, L. Oxidative Stress as a Potential Mechanism Underlying Membrane Hyperexcitability in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O.; Gerke-Duncan, M.B.; Holsinger, R.M.D. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.L.; Gong, X.X.; Qin, Z.H.; Wang, Y. Molecular mechanisms of excitotoxicity and their relevance to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases-an update. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025, 46, 3129–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, U.C.; Bhol, N.K.; Swain, S.K.; Samal, R.R.; Nayak, P.K.; Raina, V.; Panda, S.K.; Kerry, R.G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. Oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders: Mechanisms and implications. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Negrao, R.; Valente, I.; Castela, A.; Duarte, D.; Guardao, L.; Magalhaes, P.J.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Guimaraes, J.T.; Gomes, P.; et al. Xanthohumol modulates inflammation, oxidative stress, and angiogenesis in type 1 diabetic rat skin wound healing. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 2047–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.O.; Oliveira, R.; Johansson, B.; Guido, L.F. Dose-Dependent Protective and Inductive Effects of Xanthohumol on Oxidative DNA Damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 54, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazar, J.; Zegura, B.; Lah, T.T.; Filipic, M. Protective effects of xanthohumol against the genotoxicity of benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline (IQ) and tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BOOH) in HepG2 human hepatoma cells. Mutat. Res. 2007, 632, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kac, J.; Plazar, J.; Mlinaric, A.; Zegura, B.; Lah, T.T.; Filipic, M. Antimutagenicity of hops (Humulus lupulus L.): Bioassay-directed fractionation and isolation of xanthohumol. Phytomedicine 2008, 15, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilano, K.; Baldelli, S.; Ciriolo, M.R. Glutathione: New roles in redox signaling for an old antioxidant. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutbier, S.; Spreng, A.S.; Delp, J.; Schildknecht, S.; Karreman, C.; Suciu, I.; Brunner, T.; Groettrup, M.; Leist, M. Prevention of neuronal apoptosis by astrocytes through thiol-mediated stress response modulation and accelerated recovery from proteotoxic stress. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 2101–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokra, D.; Joskova, M.; Mokry, J. Therapeutic Effects of Green Tea Polyphenol (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) in Relation to Molecular Pathways Controlling Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 806470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Moore, A.N.; Redell, J.B.; Dash, P.K. Enhancing expression of Nrf2-driven genes protects the blood brain barrier after brain injury. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 10240–10248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kensler, T.W.; Egner, P.A.; Agyeman, A.S.; Visvanathan, K.; Groopman, J.D.; Chen, J.G.; Chen, T.Y.; Fahey, J.W.; Talalay, P. Keap1-nrf2 signaling: A target for cancer prevention by sulforaphane. Top. Curr. Chem. 2013, 329, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasuriya, R.; Dhamodharan, U.; Ali, D.; Ganesan, K.; Xu, B.; Ramkumar, K.M. Targeting Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway by bioactive natural agents: Possible therapeutic strategy to combat liver disease. Phytomedicine 2021, 92, 153755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E.; Esteras, N. Multitarget Effects of Nrf2 Signalling in the Brain: Common and Specific Functions in Different Cell Types. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubarak, M.M.; Pagano Zottola, A.C.; Larrieu, C.M.; Cuvellier, S.; Daubon, T.; Martin, O.C.B. Exploring the multifaceted role of NRF2 in brain physiology and cancer: A comprehensive review. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2024, 6, vdad160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kensler, T.W.; Wakabayashi, N.; Biswal, S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Huitron, R.; Ugalde Muniz, P.; Pineda, B.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Rios, C.; Perez-de la Cruz, V. Quinolinic acid: An endogenous neurotoxin with multiple targets. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Ho, Y.H.; Hung, C.F.; Kuo, J.R.; Wang, S.J. Xanthohumol, an active constituent from hope, affords protection against kainic acid-induced excitotoxicity in rats. Neurochem. Int. 2020, 133, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttari, B.; Tramutola, A.; Rojo, A.I.; Chondrogianni, N.; Saha, S.; Berry, A.; Giona, L.; Miranda, J.P.; Profumo, E.; Davinelli, S.; et al. Proteostasis Decline and Redox Imbalance in Age-Related Diseases: The Therapeutic Potential of NRF2. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Kostov, R.V.; Kazantsev, A.G. The role of Nrf2 signaling in counteracting neurodegenerative diseases. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3576–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, C.; Riera-Ponsati, L.; Kauppinen, S.; Klitgaard, H.; Erler, J.T.; Hansen, S.N. Targeting the NRF2 pathway for disease modification in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1437939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hops Extract (mg/kg/day) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Peroxidation (µmol MDA/mg Protein) | Control | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| Cortex | 18.94 ± 2.4 | 18.29 ± 2.1 | 17.75 ± 2.9 | 15.87 ± 4.2 |

| Striatum | 19.50 ± 3.1 | 13.02 ± 0.9 | 11.54 ± 3.0 | 12.56 ± 3.3 |

| Hippocampus | 19.85 ± 2.9 | 14.04 ± 1.6 | 12.77 ± 1.5 | 12.52 ± 1.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ortega, D.R.; Hernández Pérez, E.R.; Gutiérrez Magdaleno, M.; Meza-Sosa, K.F.; Pineda Calderas, L.; Álvarez Silva, M.J.; Vázquez Cervantes, G.I.; González Esquivel, D.F.; González Alfonso, W.L.; Navarro Cossio, J.A.; et al. Hops (Humulus lupulus) Extract Enhances Redox Resilience and Attenuates Quinolinic Acid-Induced Excitotoxic Damage in the Brain. Nutrients 2026, 18, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010152

Ortega DR, Hernández Pérez ER, Gutiérrez Magdaleno M, Meza-Sosa KF, Pineda Calderas L, Álvarez Silva MJ, Vázquez Cervantes GI, González Esquivel DF, González Alfonso WL, Navarro Cossio JA, et al. Hops (Humulus lupulus) Extract Enhances Redox Resilience and Attenuates Quinolinic Acid-Induced Excitotoxic Damage in the Brain. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010152

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtega, Daniela Ramírez, Erick R. Hernández Pérez, Montserrat Gutiérrez Magdaleno, Karla F. Meza-Sosa, Lucia Pineda Calderas, María José Álvarez Silva, Gustavo I. Vázquez Cervantes, Dinora F. González Esquivel, Wendy Leslie González Alfonso, Javier Angel Navarro Cossio, and et al. 2026. "Hops (Humulus lupulus) Extract Enhances Redox Resilience and Attenuates Quinolinic Acid-Induced Excitotoxic Damage in the Brain" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010152

APA StyleOrtega, D. R., Hernández Pérez, E. R., Gutiérrez Magdaleno, M., Meza-Sosa, K. F., Pineda Calderas, L., Álvarez Silva, M. J., Vázquez Cervantes, G. I., González Esquivel, D. F., González Alfonso, W. L., Navarro Cossio, J. A., Ovalle Rodríguez, P., Flores, I., Salazar, A., Gómez-Manzo, S., Pineda, B., & Pérez de la Cruz, V. (2026). Hops (Humulus lupulus) Extract Enhances Redox Resilience and Attenuates Quinolinic Acid-Induced Excitotoxic Damage in the Brain. Nutrients, 18(1), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010152