Nutrition Patterns, Metabolic and Psychological State Among High-Weight Young Adults: A Network Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Factors Associated with Overweight and Obesity Among Young Adults

1.2. Justification and Aims of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Network Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

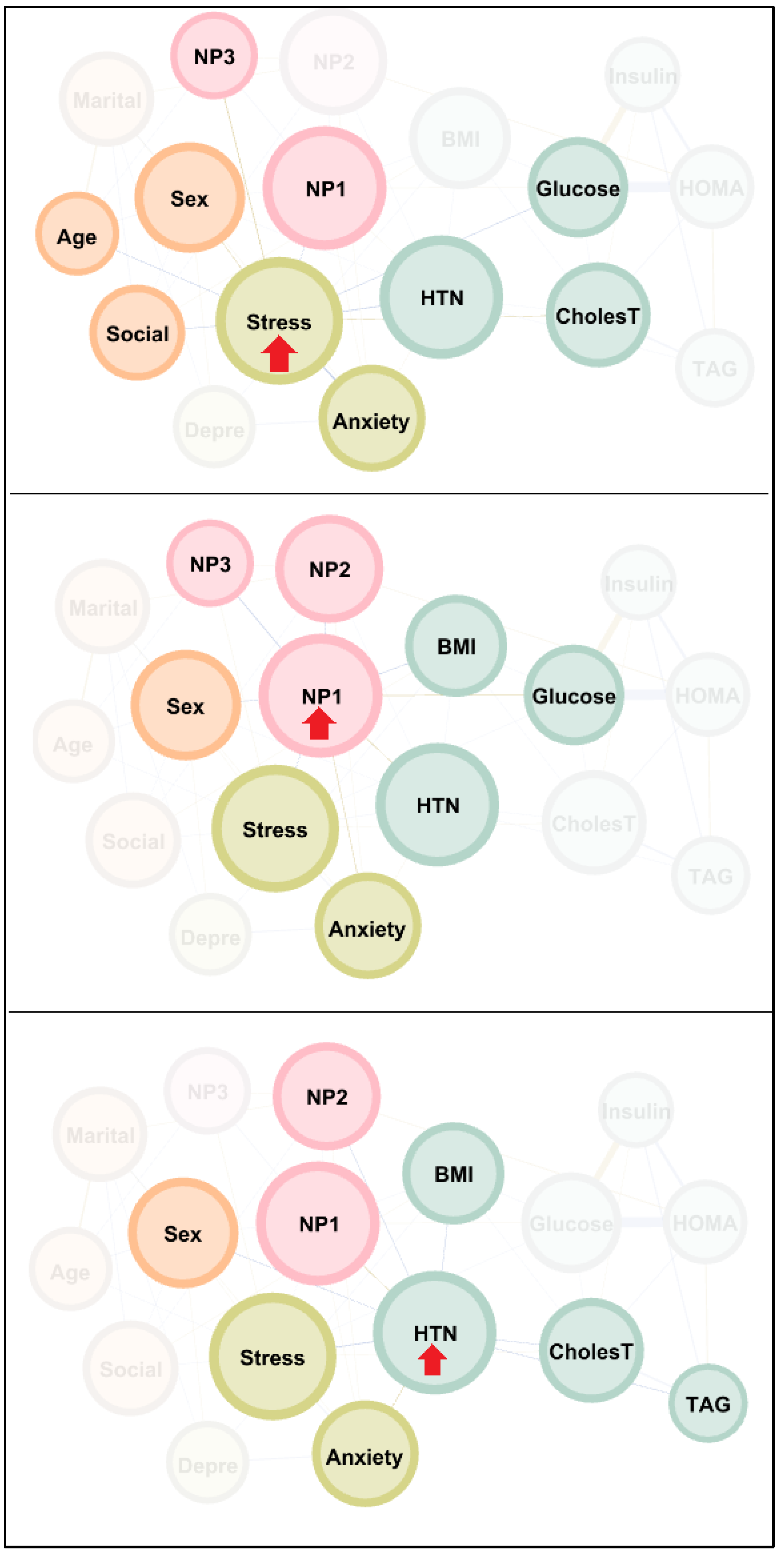

3.2. Network Visualization

3.3. Centrality Indexes in the Network

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations and Proposals for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, S.K.; Mohammed, R.A. Obesity: Prevalence, causes, consequences, management, preventive strategies and future research directions. Metab. Open 2025, 27, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.P.; Nelson, D.R.; Boye, K.S.; Mather, K.J. Prevalence of complications and comorbidities associated with obesity: A health insurance claims analysis. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbury, S.; Oyebode, O.; van Rens, T.; Barber, T.M. Obesity Stigma: Causes, Consequences, and Potential Solutions. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundi, H.; Amin, Z.M.; Friedman, M.; Hagan, K.; Al-Kindi, S.; Javed, Z.; Nasir, K. Association of Obesity With Psychological Distress in Young Adults: Patterns by Sex and Race or Ethnicity. JACC. Adv. 2024, 3, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galler, A.; Thönnes, A.; Joas, J.; Joisten, C.; Körner, A.; Reinehr, T.; Röbl, M.; Schauerte, G.; Siegfried, W.; Weghuber, D.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of children, adolescents and young adults with overweight or obesity and mental health disorders. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telleria-Aramburu, N.; Arroyo-Izaga, M. Risk factors of overweight/obesity-related lifestyles in university students: Results from the EHU12/24 study. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didarloo, A.; Khalili, S.; Aghapour, A.A.; Moghaddam-Tabrizi, F.; Mousavi, S.M. Determining intention, fast food consumption and their related factors among university students by using a behavior change theory. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElBarazi, A.; Tikamdas, R. Association between university student junk food consumption and mental health. Nutr. Health 2024, 30, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondevila-Gascón, J.F.; Berbel-Giménez, G.; Vidal-Portés, E.; Hurtado-Galarza, K. Ultra-Processed Foods in University Students: Implementing Nutri-Score to Make Healthy Choices. Healthcare 2022, 10, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffetone, P.; Laursen, P.B. Refined carbohydrates and the overfat pandemic: Implications for brain health and public health policy. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1585680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mambrini, S.P.; Menichetti, F.; Ravella, S.; Pellizzari, M.; De Amicis, R.; Foppiani, A.; Battezzati, A.; Bertoli, S.; Leone, A. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Incidence of Obesity and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Adults: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Hu, W.; Huang, J.; Tan, B.; Ma, F.; Xing, C.; Yuan, L. Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of cardiovascular events: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 69, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, L.; Patel, C.; Lovecka, L.; Gardani, M.; Walasek, L.; Ellis, J.; Meyer, C.; Johnson, S.; Tang, N.K.Y. Improving university students’ mental health using multi-component and single-component sleep interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2022, 100, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulis, S.; Falbová, D.; Hozáková, A.; Vorobel’ová, L. Sex-Specific Interrelationships of Sleeping and Nutritional Habits with Somatic Health Indicators in Young Adults. Bratisl. Med. J. 2025, 126, 2410–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, C.L.; Skogen, J.C.; Hysing, M.; Harvey, A.G.; Vedaa, Ø.; Sivertsen, B. Sleep duration and mental health in young adults. Sleep Med. 2024, 115, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S.; Cui, H.; Wang, G. Metabolomic signature between metabolically healthy overweight/obese and metabolically unhealthy overweight/obese: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 991–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Samuelsson, M.; Tárraga López, P.J.; López-González, Á.A.; Busquets-Cortés, C.; Obrador de Hevia, J.; Ramírez-Manent, J.I. Evaluation of Type 2 Diabetes Risk in Individuals with or Without Metabolically Healthy Obesity. Biology 2025, 14, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Y.; Zhou, L.J.; Ma, K.L.; Hao, R.; Li, M. MHO or MUO? White adipose tissue remodeling. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. Metabolically Healthy Obesity. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, bnaa004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.C.; Smith, G.I.; Palacios, H.H.; Farabi, S.S.; Yoshino, M.; Yoshino, J.; Cho, K.; Davila-Roman, V.G.; Shankaran, M.; Barve, R.A.; et al. Cardiometabolic characteristics of people with metabolically healthy and unhealthy obesity. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 745–761.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.; Seo, I.H.; Lee, Y.J. Serum γ-glutamyltransferase level and incidence risk of metabolic syndrome in community dwelling adults: Longitudinal findings over 12 years. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya-Cano, E.; Molina-Luque, R.; Vaquero-Abellán, M.; Molina-Recio, G.; Jiménez-Mérida, R.; Romero-Saldaña, M. Metabolic syndrome and transaminases: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhameed, F.; Kite, C.; Lagojda, L.; Dallaway, A.; Chatha, K.K.; Chaggar, S.S.; Dalamaga, M.; Kassi, E.; Kyrou, I.; Randeva, H.S. Non-invasive Scores and Serum Biomarkers for Fatty Liver in the Era of Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Comprehensive Review From NAFLD to MAFLD and MASLD. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 13, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Pugliese, G.; de Alteriis, G.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S. Metabolically healthy obesity (MHO) vs. metabolically unhealthy obesity (MUO) phenotypes in PCOS: Association with endocrine-metabolic profile, adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and body composition. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahapary, D.L.; Pratisthita, L.B.; Fitri, N.A.; Marcella, C.; Wafa, S.; Kurniawan, F.; Rizka, A.; Tarigan, T.J.E.; Harbuwono, D.S.; Purnamasari, D.; et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of insulin resistance: Focusing on the role of HOMA-IR and Tryglyceride/glucose index. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2022, 16, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.H.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Han, J.H. Comparison of triglyceride-glucose index and HOMA-IR for predicting prevalence and incidence of metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. NMCD 2022, 32, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, O.A.; Cardona, E.C.; Ramírez, D.; González, M.M.; Castaño-Osorio, J.C. Obesity and inflammation in students of a Colombian public university. Rev. Salud Publica 2020, 22, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillet, M.A.; Grouzet, F.M.E. Understanding changes in eating behavior during the transition to university from a self-determination theory perspective: A systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, N.; Abbas, U.; Arif, H.E.; Uqaili, A.A.; Khowaja, M.A.; Hussain, N.; Khan, M. From plate to profile: Investigating the influence of dietary habits and inactive lifestyle on lipid profile in medical students at clerkship. BMC Nutr. 2024, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benaich, S.; Mehdad, S.; Andaloussi, Z.; Boutayeb, S.; Alamy, M.; Aguenaou, H.; Taghzouti, K. Weight status, dietary habits, physical activity, screen time and sleep duration among university students. Nutr. Health 2021, 27, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, K.; Cáceres-Durán, M.A.; Orellana, C.; Osorio, M.; Simón, L. Nutritional imbalances among university students and the urgent need for educational and nutritional interventions. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1551130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafiz, A.A.; Gallagher, A.M.; Devine, L.; Hill, A.J. University student practices and perceptions on eating behaviours whilst living away from home. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 117, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, S.H.; Saeedi, A.A.; Baamer, M.K.; Shalabi, A.F.; Alzahrani, A.M. Eating habits among medical students at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 13, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, N.S.; de Paula, W.; de Aguiar, A.S.; Meireles, A.L. Absence of religious beliefs, unhealthy eating habits, illicit drug abuse, and self-rated health is associated with alcohol and tobacco use among college students, PADu study. J. Public Health 2022, 30, 1447–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, R.N.A. Silent Effects of High Salt: Risks Beyond Hypertension and Body’s Adaptation to High Salt. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, A.; Vadiveloo, M.; Laforge, R.G.; Melanson, K.J. Dietary contributors to fermentable carbohydrate intake in healthy American college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 72, 2577–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic Turnic, T.; Jakovljevic, V.; Strizhkova, Z.; Polukhin, N.; Ryaboy, D.; Kartashova, M.; Korenkova, M.; Kolchina, V.; Reshetnikov, V. The Association between Marital Status and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diseases 2024, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onita, B.M.; Pereira, J.L.; Mielke, G.I.; Barbosa, J.P.D.A.S.; Fisberg, R.M.; Florindo, A.A. Obesity sociodemographic and behavioral factors: A longitudinal study. Cad. Saude Publica 2024, 40, e00103623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pou, S.A.; Diaz, M.D.P.; Velázquez, G.A.; Aballay, L.R. Sociodemographic disparities and contextual factors in obesity: Updated evidence from a National Survey of Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 3377–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Valtier, M.C.; Pacheco-Pérez, L.A.; Velarde-Valenzuela, L.A.; Ruiz-González, K.J.; Cárdenas-Villarreal, V.; Gutiérrez-Valverde, J.M. Social network support and risk factors for obesity and overweight in adolescents. Apoyo en redes sociales y factores de riesgo de sobrepeso y obesidad en adolescentes. Enferm. Clin. 2021, 31, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, S.E.; Sung, M.K. Sex and Gender Differences in Obesity: Biological, Sociocultural, and Clinical Perspectives. World J. Men’s Health 2025, 43, 758–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Pan, Y.; Deng, H. Effect of marriage on overweight and obesity: Evidence from China. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Shin, A.; Cho, S.; Choi, J.Y.; Kang, D.; Lee, J.K. Marital status and the prevalence of obesity in a Korean population. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anekwe, C.V.; Jarrell, A.R.; Townsend, M.J.; Gaudier, G.I.; Hiserodt, J.M.; Stanford, F.C. Socioeconomics of obesity. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020, 9, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkowski, O.S.; Harvey, J.; Townsend, N.P.; Kelson, M.J.; Foster, C.E.M.; Western, M.J. Enablers and barriers to physical activity among older adults of low socio-economic status: A systematic review of qualitative literature. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2025, 22, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkowski, O.S.; Harvey, J.; Townsend, N.P.; Kelson, M.J.; Foster, C.E.M.; Western, M.J. Physical Activity Inequalities in Later Life consortium. Correlates and determinants of physical activity among older adults of lower versus higher socio-economic status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2025, 22, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnefaie, K.; Dungan, J.R. Reproductive-associated risk factors and incident coronary heart disease in women: An umbrella review. Am. Heart J. Plus: Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2025, 55, 100558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmoum, M.D.; Khan, S.; Usmani, W.A.; Chaudhry, R.; Ray, R.; Mahmood, A.; Afzal, M.; Mirza, M.S.S. The Effectiveness of Exercise in Reducing Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e68928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Zhang, Y.; Ryu, D.; Gariani, K. Sarcopenic obesity: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, cardiovascular disease, mortality, and management. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1185221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Ragusa, F.S.; Pegreffi, F.; Dominguez, L.J.; Barbagallo, M.; Zanetti, M.; Cereda, E. Sarcopenic obesity and health outcomes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Mentzelou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papandreou, D.; Spanoudaki, M.; Vasios, G.K.; Pavlidou, E.; Mantzorou, M.; Giaginis, C. The association of emotional eating with overweight/obesity, depression, anxiety/stress, and dietary patterns: A review of the current clinical evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, S.; Décarie-Spain, L.; Fioramonti, X.; Guiard, B.; Nakajima, S. The menace of obesity to depression and anxiety prevalence. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 33, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Ji, S.; Qu, J.; Bu, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y. Sleep quality and emotional eating in college students: A moderated mediation model of depression and physical activity levels. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako, M.; Amoah-Agyei, F.; Du, C.; Fenton, J.I.; Tucker, R.M. Emotional Eating among Ghanaian University Students: Associations with Physical and Mental Health Measures. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsmayer, D.; Eckert, G.P.; Reiff, J.; Braus, D.F. Nutrition, metabolism, brain and mental health. Der Nervenarzt 2024, 95, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yu, L.; Tong, Z.; Sun, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xing, X.; Zhao, J.V.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X. Obesity, metabolic health, and brain health: Insights from a prospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2026, 392, 120184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reivan Ortiz, G.G.; Granero, R.; Aranda-Ramírez, M.P.; Aguirre-Quezada, M.A. Association Between Nutrition Patterns and Metabolic and Psychological State Among Young Adults. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2025, 33, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morejón, Y.; Manzano, A.; Betancourt, S.; Ulloa, V. Construction of a food consumption frequency questionnaire for Ecuadorian adults, cross-sectional study. Rev. Española Nutr. Humana Dietética 2021, 25, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauce, G.; Moya-Sifontes, M.Z. Waist circumference weight index as a complementary indicator of overweight and obesity in different groups of subjects. Rev. Digit. Postgrado 2020, 9, e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-León Mandujano, A.; Morales López, S.; Álvarez Díaz, C.D.J. Correct technique for taking blood pressure in the outpatient. Rev. Fac. Med. 2016, 59, 49–55. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/facmed/v59n3/2448-4865-facmed-59-03-49.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Gordon, B.A.; Benson, A.C.; Bird, S.R.; Fraser, S.F. Resistance training improves metabolic health in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2009, 83, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Overweight and Obesity; OMS: Ginebra, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Román, F.; Santibáñez, P.; Vinet, E.V. Use of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) as a screening instrument in young people with clinical problems. Acta Investig. Psicológica 2016, 6, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingshead, A.B. Four factor index of social status. Yale J. Sociol. 2011, 8, 21–51. Available online: https://sociology.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/yjs_fall_2011.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Steinley, D. Recent Advances in (Graphical) Network Models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2021, 56, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsboom, D. Reflections on an emerging new science of mental disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 2022, 156, 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinaugh, D.J.; Hoekstra, R.H.A.; Toner, E.R.; Borsboom, D. The network approach to psychopathology: A review of the literature 2008-2018 and an agenda for future research. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2009, 3, 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V.D.; Guillaume, J.L.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, 2008, P10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, U. A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. J. Math. Sociol. 2001, 25, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.J.; Moore, J.A.; Griffiths, A.R.; Cousins, A.L.; Young, H.A. Unveiling Dietary Complexity: A Scoping Review and Reporting Guidance for Network Analysis in Dietary Pattern Research. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velilla, T.A.; Guijarro, C.; Ruiz, R.C.; Piñero, M.R.; Francisco Valderrama Marcos, J.; López, A.M.B.; López, A.M.; Antonio García Donaire, J.; Obaya, J.C.; Castilla Guerra, L.; et al. Consensus document for lipid profile determination and reporting in Spanish clinical laboratories. What parameters should be included in a basic lipid profile? Nefrologia 2023, 43, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alser, M.; Naja, K.; Elrayess, M.A. Mechanisms of body fat distribution and gluteal-femoral fat protection against metabolic disorders. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1368966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.C.; O’Neill, S.; Beck, B.R.; Forwood, M.R.; Khoo, S.K. Comparison of obesity and metabolic syndrome prevalence using fat mass index, body mass index and percentage body fat. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rog, J.; Nowak, K.; Wingralek, Z. The Relationship between Psychological Stress and Anthropometric, Biological Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengton, R.; Schoenmakers, M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Boon, M.R.; van Rossum, E.F.C. Glucocorticoids and HPA axis regulation in the stress-obesity connection: A comprehensive overview of biological, physiological and behavioural dimensions. Clin. Obes. 2025, 15, e12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachan, L.; Verma, P.; Nasir, A. Assessment of anxiety, depression and serum cortisol levels in invasive and non-invasive treated patients-A physiobiochemical study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 15, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, M.; Nouri, M.; Kohanmoo, A.; Homayounfar, R.; Akhlaghi, M. The influence of gender and waist circumference in the association of body fat with cardiometabolic diseases. BMC Nutr. 2025, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordito Soler, M.; López-González, Á.A.; Tárraga López, P.J.; Martínez-Almoyna Rifá, E.; Martorell Sánchez, C.; Vicente-Herrero, M.T.; Paublini, H.; Ramírez-Manent, J.I. Association of sociodemographic variables and healthy habits with body and visceral fat values in Spanish workers. Medicina 2025, 61, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, M. Gender differences in protein consumption and body composition: The influence of socioeconomic status on dietary choices. Foods 2025, 14, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ruan, X.Y.; Ma, W. The association between a body shape index and depressive symptoms: A cross-sectional study using NHANES data (2011–2018). Front. Nutr. 2025, 11, 1510218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Bartolomucci, A.; Kawachi, I. The multiple roles of life stress in metabolic disorders. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, Á.A.; Martínez-Almoyna Rifá, E.; Paublini Oliveira, H.; Martorell Sánchez, C.; Tárraga López, P.J.; Ramírez-Manent, J.I. Association between sociodemographic variables, healthy habits and stress with metabolic syndrome. A descriptive, cross-sectional study. Semergen 2025, 51, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, R. Stress and substance use disorders: Risk, relapse, and treatment outcomes. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e172883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscaritoli, M. The impact of nutrients on mental health and well-being: Insights from the literature. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 656290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucklidge, J.J.; Johnstone, J.M.; Kaplan, B.J. Nutrition provides the essential foundation for optimizing mental health. Evid. -Based Pract. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2021, 6, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Ma, D. The Role of Nutrition and Body Composition on Metabolism. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Nasreen, A.; Menzel, A.; Gasmi Benahmed, A.; Pivina, L.; Noor, S.; Peana, M.; Chirumbolo, S.; Bjørklund, G. Neurotransmitters regulation and food intake: The role of dietary sources in neurotransmission. Molecules 2022, 28, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.K.; Dhuli, K.; Donato, K.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Connelly, S.T.; Bellinato, F.; Gisondi, P.; et al. Main nutritional deficiencies. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E93–E101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohseni, P.; Khalili, D.; Djalalinia, S.; Mohseni, H.; Farzadfar, F.; Shafiee, A.; Izadi, N. The synergistic effect of obesity and dyslipidemia on hypertension: Results from the STEPS survey. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoh, P.; Olusanya, D.A.; Erinne, O.C.; Achara, K.E.; Aboaba, A.O.; Abiodun, R.; Gbigbi-Jackson, G.A.; Abiodun, R.F.; Oredugba, A.; Dieba, R.; et al. An Integrated Pathophysiological and Clinical Perspective of the Synergistic Effects of Obesity, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia on Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e72443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wen, C.P.; Tu, H.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Xu, A.; Li, W.; Wu, X. Metabolic syndrome including both elevated blood pressure and elevated fasting plasma glucose is associated with higher mortality risk: A prospective study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamooya, B.M.; Siame, L.; Muchaili, L.; Masenga, S.K.; Kirabo, A. Metabolic syndrome: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and current therapeutic approaches. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1661603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Wei, P.; Suzauddula, M.; Nime, I.; Feroz, F.; Acharjee, M.; Pan, F. The interplay of factors in metabolic syndrome: Understanding its roots and complexity. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | Closeness Centrality | Harmonic Closeness Centrality | Betweenness Centrality | Authority | HUB | Modularity | Clustering. Coefficient | Number Triangles | Eigenvector Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.5926 | 0.6979 | 6.6262 | 0.2829 | 0.2829 | 3 | 0.3810 | 8 | 0.7852 |

| Age | 0.5000 | 0.5833 | 1.5056 | 0.1632 | 0.1632 | 3 | 0.5000 | 3 | 0.4526 |

| Marital | 0.5333 | 0.6458 | 4.4500 | 0.2141 | 0.2141 | 3 | 0.4000 | 6 | 0.5945 |

| Social | 0.5517 | 0.6354 | 2.7444 | 0.2161 | 0.2161 | 3 | 0.3000 | 3 | 0.6008 |

| BMI | 0.5926 | 0.6771 | 8.1968 | 0.2434 | 0.2434 | 3 | 0.2667 | 4 | 0.6811 |

| HTN | 0.6667 | 0.7500 | 12.8881 | 0.3399 | 0.3399 | 3 | 0.3929 | 11 | 0.9491 |

| Glucose | 0.5926 | 0.6771 | 7.3889 | 0.2336 | 0.2336 | 2 | 0.4667 | 7 | 0.6604 |

| Insulin | 0.4571 | 0.5521 | 0.3333 | 0.1237 | 0.1237 | 2 | 0.8333 | 5 | 0.3578 |

| CholesT | 0.6154 | 0.7083 | 8.8746 | 0.2521 | 0.2521 | 1 | 0.4762 | 10 | 0.7153 |

| TAG | 0.4848 | 0.5729 | 1.3111 | 0.1382 | 0.1382 | 1 | 0.6667 | 4 | 0.3961 |

| HOMA | 0.5333 | 0.6250 | 5.2429 | 0.1606 | 0.1606 | 2 | 0.5000 | 5 | 0.4608 |

| Depre | 0.5000 | 0.5833 | 1.6500 | 0.1587 | 0.1587 | 3 | 0.3333 | 2 | 0.4406 |

| Anxiety | 0.5926 | 0.6771 | 4.2667 | 0.2658 | 0.2658 | 3 | 0.4667 | 7 | 0.7377 |

| Stress | 0.6957 | 0.7813 | 17.3468 | 0.3589 | 0.3589 | 3 | 0.3333 | 12 | 1.0000 |

| NP1 | 0.6667 | 0.7500 | 7.9389 | 0.3429 | 0.3429 | 3 | 0.4286 | 12 | 0.9536 |

| NP2 | 0.6400 | 0.7188 | 12.8690 | 0.2710 | 0.2710 | 3 | 0.2857 | 6 | 0.7552 |

| NP3 | 0.5161 | 0.5938 | 1.3667 | 0.1792 | 0.1792 | 3 | 0.5000 | 3 | 0.4965 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Reivan Ortiz, G.G.; Granero, R.; Maraver-Capdevila, L.; Aguirre-Quejada, A. Nutrition Patterns, Metabolic and Psychological State Among High-Weight Young Adults: A Network Approach. Nutrients 2026, 18, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010145

Reivan Ortiz GG, Granero R, Maraver-Capdevila L, Aguirre-Quejada A. Nutrition Patterns, Metabolic and Psychological State Among High-Weight Young Adults: A Network Approach. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleReivan Ortiz, Geovanny Genaro, Roser Granero, Laura Maraver-Capdevila, and Alejandra Aguirre-Quejada. 2026. "Nutrition Patterns, Metabolic and Psychological State Among High-Weight Young Adults: A Network Approach" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010145

APA StyleReivan Ortiz, G. G., Granero, R., Maraver-Capdevila, L., & Aguirre-Quejada, A. (2026). Nutrition Patterns, Metabolic and Psychological State Among High-Weight Young Adults: A Network Approach. Nutrients, 18(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010145