School-Age Neurodevelopmental and Atopy Outcomes in Extremely Preterm Infants: Follow-Up from the Single Versus Triple-Strain Bifidobacterium Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

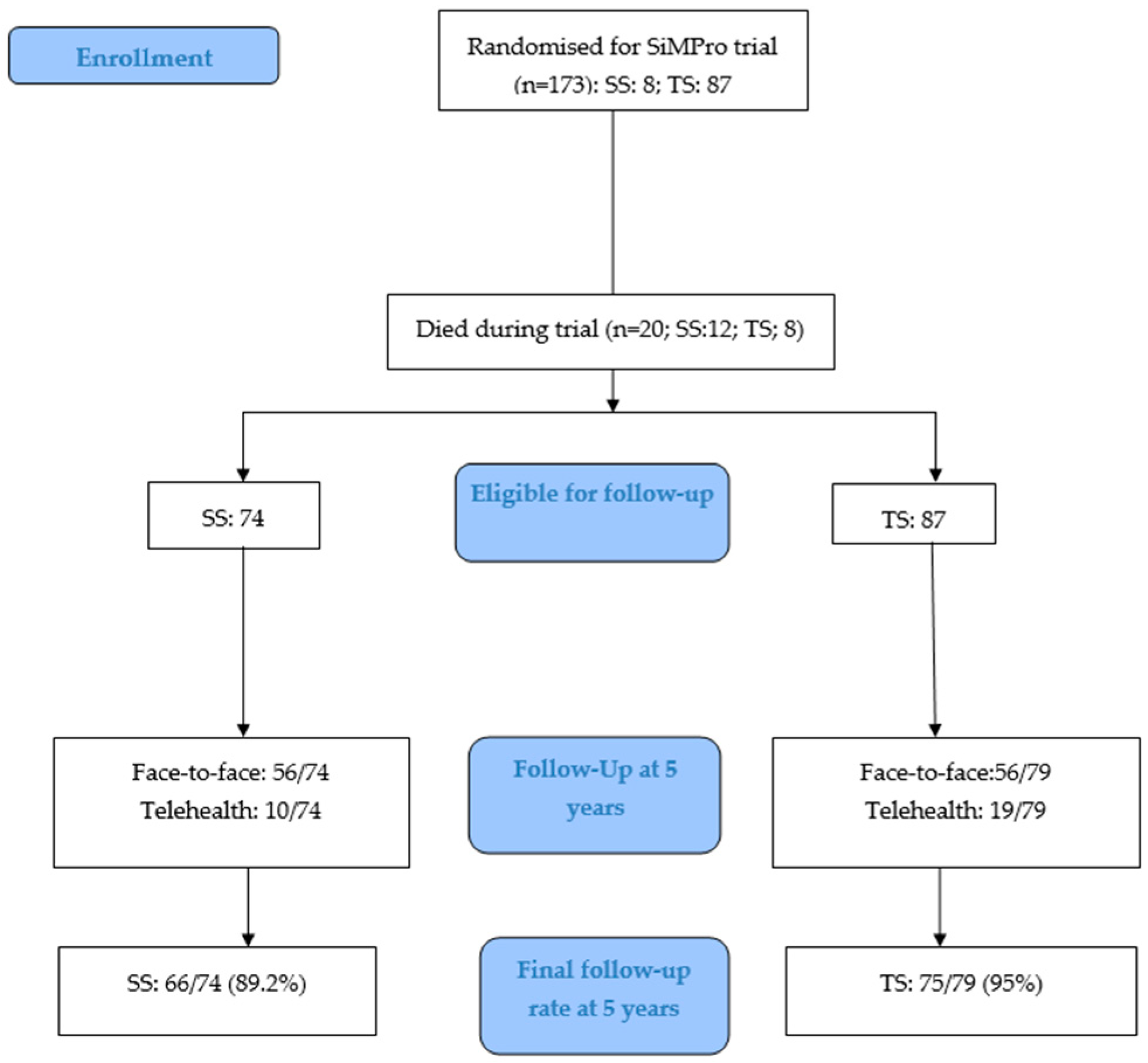

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Neurodevelopmental and Neurobehavioral Outcomes

2.2. Growth, Blood Pressure, and Atopy Related Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis for Clinical Data

3. Results

3.1. Neurodevelopmental and Neurobehavioral Outcomes

3.2. Growth Outcomes

3.3. Blood Pressure and Atopy-Related Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Ådén, U.; Farooqi, A.; Hellstrom-Westas, L.; Sävman, K.; Abrahamsson, T.; Björklund, L.J.; Domellöf, M.; Elfvin, A.; Ingemansson, F.; Serenius, F.; et al. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes in extremely preterm infants born at 22–26 weeks gestation: A follow-up of 2–2.5 years across two Swedish national cohorts from 2004–2007 to 2014–2016. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2025. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierrat, V.; Marchand-Martin, L.; Arnaud, C.; Kaminski, M.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Lebeaux, C.; Bodeau-Livinec, F.; Morgan, A.S.; Goffinet, F.; Marret, S.; et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years for preterm children born at 22 to 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. BMJ 2017, 358, j3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marks, I.R.; Doyle, L.W.; Mainzer, R.M.; Spittle, A.J.; Clark, M.; A Boland, R.; Anderson, P.J.; Cheong, J.L. Neurosensory, cognitive and academic outcomes at 8 years in children born 22–23 weeks’ gestation compared with more mature births. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2024, 109, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zou, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Yang, L. Pathogenesis from the microbial-gut-brain axis in white matter injury in preterm infants: A review. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1051689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, T.; Shi, Y. Role of the gut-microbiota-metabolite-brain axis in the pathogenesis of preterm brain injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, K.M.; Strobel, K.M.; Hendrixson, D.T.; Brandon, O.; Hair, A.B.; Workneh, R.; Abayneh, M.; Nangia, S.; Hoban, R.; Kolnik, S.; et al. Nutrition and the gut-brain axis in neonatal brain injury and development. Semin. Perinatol. 2024, 48, 151927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vievermanns, K.; Dierikx, T.H.; Oldenburger, N.J.; Jamaludin, F.S.; Niemarkt, H.J.; de Meij, T.G.J. Effect of probiotic supplementation on the gut microbiota in very preterm infants: A systematic review. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2024, 110, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talat, A.; Zuberi, A.; Khan, A.U. Unravelling the Gut-Microbiome-Brain Axis: Implications for Infant Neurodevelopment and Future Therapeutics. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X. The microbiota-gut-brain axis and neurodevelopmental disorders. Protein Cell 2023, 14, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, J.C.; Im, S.-H. The gut-immune-brain axis in neurodevelopment and neurological disorders. Microbiome Res. Rep. 2022, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prasad, J.D.; van de Looij, Y.; Gunn, K.C.; Ranchhod, S.M.; White, P.B.; Berry, M.J.; Bennet, L.; Sizonenko, S.V.; Gunn, A.J.; Dean, J.M. Long-term coordinated microstructural disruptions of the developing neocortex and subcortical white matter after early postnatal systemic inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 94, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, J.; Miller, S.P. Preterm brain Injury: White matter injury. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2019, 162, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercado-Monroy, J.; Falfán-Cortés, R.N.; Muñóz-Pérez, V.M.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Castro-Rosas, J. Probiotics as modulators of intestinal barrier integrity and immune homeostasis: A comprehensive review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Li, D.; Wang, C.-Z.; Wan, J.-Y.; Yao, H.; Yuan, C.-S. Probiotics fortify intestinal barrier function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1143548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Snigdha, S.; Ha, K.; Tsai, P.; Dinan, T.G.; Bartos, J.D.; Shahid, M. Probiotics: Potential novel therapeutics for microbiota-gut-brain axis dysfunction across gender and lifespan. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 231, 107978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, K. The Effect of Probiotics on the Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids by Human Intestinal Microbiome. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ikeda, T.; Nishida, A.; Yamano, M.; Kimura, I. Short-chain fatty acid receptors and gut microbiota as therapeutic targets in metabolic, immune, and neurological diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 239, 108273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, E.; Matsunaga, M.; Fujihara, H.; Kajiwara, T.; Takeda, A.K.; Watanabe, S.; Hagihara, K.; Myowa, M. Temperament in Early Childhood Is Associated With Gut Microbiota Composition and Diversity. Dev. Psychobiol. 2024, 66, e22542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMath, A.L.; Aguilar-Lopez, M.; Cannavale, C.N.; Khan, N.A.; Donovan, S.M. A systematic review on the impact of gastrointestinal microbiota composition and function on cognition in healthy infants and children. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1171970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beghetti, I.; Barone, M.; Turroni, S.; Biagi, E.; Sansavini, A.; Brigidi, P.; Corvaglia, L.; Aceti, A. Early-life gut microbiota and neurodevelopment in preterm infants: Any role for Bifidobacterium? Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1773–1777, Erratum in Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04382-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cao, M.; Yang, X.; Wang, X. Effects of early-life gut microbiota on the neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants: A multi-center, longitudinal observational study in China. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 1733–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.B.; Huang, H.; Ning, Y.; Xiao, J. Probiotics in the New Era of Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs): HMO Utilization and Beneficial Effects of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis M-63 on Infant Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, S.; Cai, J.; Su, Q.; Li, Q.; Meng, X. Human milk oligosaccharides combine with Bifidobacterium longum to form the “golden shield” of the infant intestine: Metabolic strategies, health effects, and mechanisms of action. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2430418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tillmann, S.; Awwad, H.M.; Eskelund, A.R.; Treccani, G.; Geisel, J.; Wegener, G.; Obeid, R. Probiotics Affect One-Carbon Metabolites and Catecholamines in a Genetic Rat Model of Depression. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1701070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dubey, H.; Roychoudhury, R.; Alex, A.; Best, C.; Liu, S.; White, A.; Carlson, A.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A.; Mansfield, L.S.; Knickmeyer, R. Effect of Human Infant Gut Microbiota on Mouse Behavior, Dendritic Complexity, and Myelination. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dai, K.; Ding, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Rong, Z. Gut Microbiota and Neurodevelopment in Preterm Infants: Mechanistic Insights and Prospects for Clinical Translation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, A.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Dey, S.; Kumar, Y.; Malviya, R.; Prajapati, B.G.; Chaiyasut, C. Probiotics as modulators of gut-brain axis for cognitive development. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1348297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- InInsel, R.A.; Jarman, J.B.; Torres, P.J.; Van Dien, S.; Culler, S.J.; de Vos, W.M. Restoring a gut Bifidobacterium community in early infancy. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 2012–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athalye-Jape, G.; Esvaran, M.; Patole, S.; Simmer, K.; Nathan, E.; Doherty, D.; Keil, A.; Rao, S.; Chen, L.; Chandrasekaran, L.; et al. Effect of single versus multistrain probiotic in extremely preterm infants: A randomised trial. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022, 9, e000811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chin, W.-C.; Wu, W.-C.; Hsu, J.-F.; Tang, I.; Yao, T.-C.; Huang, Y.-S. Correlation Analysis of Attention and Intelligence of Preterm Infants at Preschool Age: A Premature Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Warschausky, S.; Raiford, S.E. Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology; Kreutzer, J.S., DeLuca, J., Caplan, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, D.M.; Ricci, M.; Mirra, F.; Venezia, I.; Mallardi, M.; Pede, E.; Mercuri, E. Longitudinal Cognitive Assessment in Low-Risk Very Preterm Infants. Medicina 2022, 58, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gustafsson, B.M.; Proczkowska-Björklund, M.; Gustafsson, P.A. Emotional and behavioural problems in Swedish preschool children rated by preschool teachers with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Levickis, P.; Sciberras, E.; McKean, C.; Conway, L.; Pezic, A.; Mensah, F.K.; Bavin, E.L.; Bretherton, L.; Eadie, P.; Prior, M.; et al. Language and social-emotional and behavioural wellbeing from 4 to 7 years: A community-based study. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Herreras, E.B. Executive Functioning Profiles in Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sparr, V.M.; Willwohl, C.F.; Fussenegger, B.; Gang, S.; Simma, B.; Konzett, K. Five-Year Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Children Born Very Preterm Between 2012 and 2018. Neuropediatrics 2025, 56, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongstad, I.; Petersson, S. Executive functions in everyday life in children born small for gestational age—A pilot study of pre-term to full-term children 3 years and younger. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Athalye-Jape, G.; Lim, M.; Nathan, E.; Sharp, M. Outcomes in extremely low birth weight (≤500 g) preterm infants: A Western Australian experience. Early Hum. Dev. 2022, 167, 105553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenton, T.R.; Samycia, L.; Elmrayed, S.; Nasser, R.; Alshaikh, B. Growth patterns by birth size of preterm children born at 24reastfeeding, specific foods in the first year of life, and asthma at 6 years of age29 gestational weeks for the first 3 years. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2024, 38, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makker, K.; Kuiper, J.R.; Brady, T.; Hong, X.; Wang, G.; Pearson, C.; Sanderson, K.; O’sHea, T.M.; Wang, X.; Aziz, K. Prematurity, Neonatal Complications, and the Development of Childhood Hypertension. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2527431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Džida, S.; Raguž, M.J.; Kraljević, D.; Nikše, T.; Mabić, M.; Pavlović, K. Prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis and their association with risk factors in children in the southern region of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). J. Asthma 2025. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, V.; de Aguiar, R.L.; Schuelter-Trevisol, F.; de Andrade, G.C.; Trevisol, D.J.; Traebert, J.; Traebert, E. Breastfeeding, specific foods in the first year of life, and asthma at 6 years of age. Front. Public Health 2025, 71, e20241970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jacobs, S.E.; Hickey, L.; Donath, S.; Opie, G.F.; Anderson, P.J.; Garland, S.M.; Cheong, J.L.Y. Probiotics, prematurity and neurodevelopment: Follow-up of a randomised trial. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2017, 1, e000176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wejryd, E.; Marchini, G.; Bang, P.; Jonsson, B.; Ådén, U.; Abrahamsson, T. Neurodevelopment and Growth 2 Years After Probiotic Supplementation in Extremely Preterm Infants: A Randomised Trial. Acta Paediatr. 2025, 114, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wejryd, E.; Marchini, G.; Frimmel, V.; Jonsson, B.; Abrahamsson, T. Probiotics promoted head growth in extremely low birthweight infants in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 108, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baucells, B.J.; Sebastiani, G.; Herrero-Aizpurua, L.; Andreu-Fernández, V.; Navarro-Tapia, E.; García-Algar, O.; Figueras-Aloy, J. Effectiveness of a probiotic combination on the neurodevelopment of the very premature infant. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shah, P.S.; Bando, N.; Lee, S.; Raghuram, K.; Beltempo, M.; Fajardo, C.; Bertelle, V.; Ly, L.G.; Banihani, R.; Alshaikh, B.N. Probiotic Receipt and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Infants <29 Weeks’ Gestation: A Cohort Study. J. Pediatr. 2025, 287, 114783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, H.; Athalye-Jape, G.; Rao, S.; Patole, S. Growth and neuro-developmental outcomes of probiotic supplemented preterm infants-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 77, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kruth, S.S.; Persad, E.; Rakow, A. Probiotic Supplements Effect on Feeding Tolerance, Growth and Neonatal Morbidity in Extremely Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharif, S.; Meader, N.; Oddie, S.J.; Rojas-Reyes, M.X.; McGuire, W. Probiotics to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 7, CD005496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rianda, D.; Agustina, R.; Setiawan, E.; Manikam, N. Effect of probiotic supplementation on cognitive function in children and adolescents: A systematic review of randomised trials. Benef. Microbes 2019, 10, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novau-Ferré, N.; Papandreou, C.; Rojo-Marticella, M.; Canals-Sans, J.; Bulló, M. Gut microbiome differences in children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder and effects of probiotic supplementation: A randomized controlled trial. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2025, 161, 105003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frerichs, N.M.; de Meij, T.G.; Niemarkt, H.J. Microbiome and its impact on fetal and neonatal brain development: Current opinion in pediatrics. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2024, 27, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fock, E.; Parnova, R. Mechanisms of Blood-Brain Barrier Protection by Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Cells 2023, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lan, Z.; Tang, X.; Lu, M.; Hu, Z.; Tang, Z. The role of short-chain fatty acids in central nervous system diseases: A bibliometric and visualized analysis with future directions. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kelly, J.R.; Minuto, C.; Cryan, J.F.; Clarke, G.; Dinan, T.G. Cross Talk: The Microbiota and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fałta, E.K.-F.; Furmańczyk, K.; Tomaszewska, A.; Olejniczak, D.; Samoliński, B.; Samolińska-Zawisza, U. Probiotics: Myths or facts about their role in allergy prevention. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 27, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasjois, R.; Gebremedhin, A.; Silva, D.; Rao, S.C.; Tessema, G.A.; Pereira, G. Probiotic Supplementation in the Neonatal Age Group and the Risk of Hospitalisation in the First Two Years: A Data Linkage Study from Western Australia. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Overall Disability | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Mild (At least one criteria) | A cognitive score between one and two standard deviations (SD) below the test mean, ambulant cerebral palsy (GMFCS level I/II) |

| Moderate (At least one criteria) | A cognitive score between two and three SD below the test mean, GMFCS level III CP (ambulant with aids), unilateral deafness |

| Severe (At least one criteria) | A cognitive score >3 SD below the test mean, GMFCS level IV/V CP, blindness (vision < 6/60), autism, bilateral deafness needing amplification |

| SS; n = 86 | TS; n = 87 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p | ||

| Sex | Female | 38 (44.2%) | 41 (47.1%) | 0.698 |

| Male | 48 (55.8%) | 46 (52.9%) | ||

| GA mean (SD) | 25.96 (1.35) | 25.79 (1.53) | 0.434 | |

| Parental education * (n = 40, missing n = 133) | 0.255 | |||

| secondary | 4 (22.2%) | 7 (31.8%) | ||

| post-secondary | 3 (16.7%) | 8 (36.4%) | ||

| tertiary | 8 (44.4%) | 4 (18.2%) | ||

| post-graduate | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (13.6%) | ||

| SEIFA decile (n = 135) * | 0.296 | |||

| 1 | 4 (6.1%) | 8 (11.1%) | ||

| 2 | 7 (10.6%) | 6 (8.3%) | ||

| 3 | 5 (7.6%) | 11 (15.3%) | ||

| 4 | 5 (7.6%) | 2 (2.8%) | ||

| 5 | 12 (18.2%) | 7 (9.7%) | ||

| 6 | 5 (7.6%) | 5 (6.9%) | ||

| 7 | 3 (4.5%) | 3 (4.2%) | ||

| 8 | 13 (19.7%) | 9 (12.5%) | ||

| 9 | 3 (4.5%) | 10 (13.9%) | ||

| 10 | 9 (13.6%) | 11 (15.3%) | ||

| SEIFA tertile * | 0.285 | |||

| 1 | 19 (29.2%) | 25 (35.7%) | ||

| 2 | 26 (40.0%) | 19 (27.1%) | ||

| 3 | 20 (30.8%) | 26 (37.1%) |

| Outcome | SS (n = 66) | TS (n = 74) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any CP | 4 (6.1%) | 4 (5.4%) | 1.000 |

| CP severity (GMFCS) 4–5 | 2 (50.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 1.000 |

| 2–3 | 2 (50.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Autism | |||

| suspected | 2 (3.0%) | 6 (8.1%) | 0.271 |

| confirmed | 2 (3.0%) | 6 (8.1%) | 0.135 |

| Autism severity level 2 | 1 (25%) | 1 (20.0%) | 1.000 |

| Autism severity level 3 | 3 (75%) | 4 (80.0%) | |

| Blindness | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| Deafness | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.000 |

| Completed WPPSI | 56 (85%) | 56 (76%) | 0.226 |

| WPPSI-IV age (yr) median (IQR) | 5.25 (5.25, 5.33) | 5.25 (5.25, 5.33) | 0.816 |

| WPPSI-IV FSIQ median (IQR) | 84 (127, 98) | 98 (84, 105) | 0.369 |

| SDQ completed $ | 15/ 56 (23%) | 16/56 (28.6%) | 0.998 |

| SDQ scores: Median (IQR) | |||

| Total difficulties | 9 (7, 15) | 15 (8.5, 17.5) | 0.132 |

| Emotional symptoms | 1 (0, 4) | 2 (0, 4) | 0.576 |

| Conduct problems | 1 (0, 3) | 3 (0.5, 4) | 0.295 |

| Hyperactive inattention | 6 (2, 8) | 6 (5, 10) | 0.176 |

| Peer relationship problems | 1 (0, 3) | 2 (0, 3.5) | 0.737 |

| Prosocial behavior | 9 (7, 9) | 6 (4, 9) | 0.132 |

| Impact | 0 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.655 |

| BRIEF completed $ | 26/56 (46.4%) | 34/56 (60.7%) | 0.317 |

| BRIEF T-scores: Median (IQR) | |||

| Inhibit scale | 52 (45.75, 67.25) | 60.5 (51, 74) | 0.139 |

| Emotional control scale | 50.5 (43, 64.5) | 57 (45, 77) | 0.324 |

| Shift scale | 48 (42.75, 62) | 52 (42, 63) | 0.520 |

| Working memory scale | 59 (49.5, 76.25) | 65 (54, 83) | 0.170 |

| Plan/organize scale | 58 (46.25, 64.25) | 64 (51, 75) | 0.129 |

| Inhibitory self-control index | 52.5 (43.75, 70.25) | 60 (49, 77) | 0.191 |

| Flexibility index | 47.5 (41.75, 66.75) | 59.5 (44, 70) | 0.366 |

| Emergent metacognition index | 58 (47, 75) | 66 (53, 82) | 0.161 |

| Global executive composite | 54 (46.5, 68.5) | 61 (51, 81) | 0.143 |

| Overall Disability Category | SS (n = 66) | TS (n = 74) | OR (95% CI) | p | aOR * (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 44 (66.7%) | 41 (55.4%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Mild | 12 (18.2%) | 16 (21.6%) | 1.43 (0.61, 3.39) | 0.415 | 1.39 (0.57, 3.34) | 0.468 |

| Moderate-severe | 10 (15.2%) | 17 (23.0%) | 1.82 (0.75, 4.44) | 0.185 | 1.77 (0.71, 4.39) | 0.218 |

| Outcome | Total n | SS Median (IQR) | TS Median (IQR) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm) | 107 | 108.0 (105.0, 110.8) | 108.0 (105.25, 112.10) | 0.701 |

| Height z score | 107 | −0.05 (−0.68, 0.54) | −0.05 (−0.63, 0.81) | 0.707 |

| Weight (kg) | 107 | 17.55 (16.16, 19.65) | 17.70 (15.85, 18.95) | 0.297 |

| Weight z score | 107 | −0.13 (−0.64, 0.63) | −0.08 (−0.75, 0.37) | 0.707 |

| HC (cm) | 107 | 50.00 (49.50, 51.63) | 50.30 (49.10, 51.55) | 0.857 |

| HC z score | 107 | −0.27 (−0.56, 0.65) | −0.10 (−0.78, 0.61) | 0.707 |

| SS (n = 74) | TS (n = 79) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p | |

| @SBP Median (IQR) | 103 (98, 107) | 103 (97.5, 107) | 0.948 |

| @DBP Median (IQR) | 65 (61, 69) | 64 (60.5, 68) | 0.414 |

| @BMI Median (IQR) | 15.14 (14.24, 16.20) | 14.89 (13.95, 15.79) | 0.220 |

| @BMI z-score Median (IQR) | −0.06 (−0.61, 0.58) | −0.21 (−0.78, 0.34) | 0.220 |

| Completed ISAAC questionnaire | 37 (50.0%) | 41 (51.9%) | 0.826 |

| |||

| Diagnosed ever | 10 (27.0%) | 12 (29.3%) | 0.478 |

| Wheezing in last 12 m | 5 (13.5%) | 8 (19.5%) | 0.553 |

| |||

| Diagnosed ever | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (9.8%) | 0.090 |

| Wheeze episodes last 12 m | 6 (16.2%) | 8 (19.5%) | 0.705 |

| Frequency of wheeze episodes in last 12 m | 0.424 | ||

| 1 | 2 (5.4%) | 1 (2.4%) | |

| 2 | 3 (8.1%) | 7 (17.1%) | |

| 3 | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| |||

| Diagnosed ever | 3 (8.1%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0.664 |

| episodes in last 12 m | 12 (32.4%) | 9 (22.0%) | 0.297 |

| |||

| Diagnosed ever | 12 (32.4%) | 12 (29.3%) | 0.762 |

| episodes in last 12 m | 5 (13.5%) | 10 (24.4%) | 0.262 |

| |||

| Diagnosed ever | 15 (40.5%) | 15 (36.6%) | 0.720 |

| episodes in last 12 m | 8 (21.6%) | 13 (31.7%) | 0.316 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Athalye-Jape, G.; Rath, C.; Esvaran, M.; Jacques, A.; Patole, S. School-Age Neurodevelopmental and Atopy Outcomes in Extremely Preterm Infants: Follow-Up from the Single Versus Triple-Strain Bifidobacterium Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2026, 18, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010141

Athalye-Jape G, Rath C, Esvaran M, Jacques A, Patole S. School-Age Neurodevelopmental and Atopy Outcomes in Extremely Preterm Infants: Follow-Up from the Single Versus Triple-Strain Bifidobacterium Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010141

Chicago/Turabian StyleAthalye-Jape, Gayatri, Chandra Rath, Meera Esvaran, Angela Jacques, and Sanjay Patole. 2026. "School-Age Neurodevelopmental and Atopy Outcomes in Extremely Preterm Infants: Follow-Up from the Single Versus Triple-Strain Bifidobacterium Randomized Controlled Trial" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010141

APA StyleAthalye-Jape, G., Rath, C., Esvaran, M., Jacques, A., & Patole, S. (2026). School-Age Neurodevelopmental and Atopy Outcomes in Extremely Preterm Infants: Follow-Up from the Single Versus Triple-Strain Bifidobacterium Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 18(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010141