Effects of a Red-Ginger-Based Multi-Nutrient Supplement on Optic Nerve Head Blood Flow in Open-Angle Glaucoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Systemic and Ocular Examinations

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

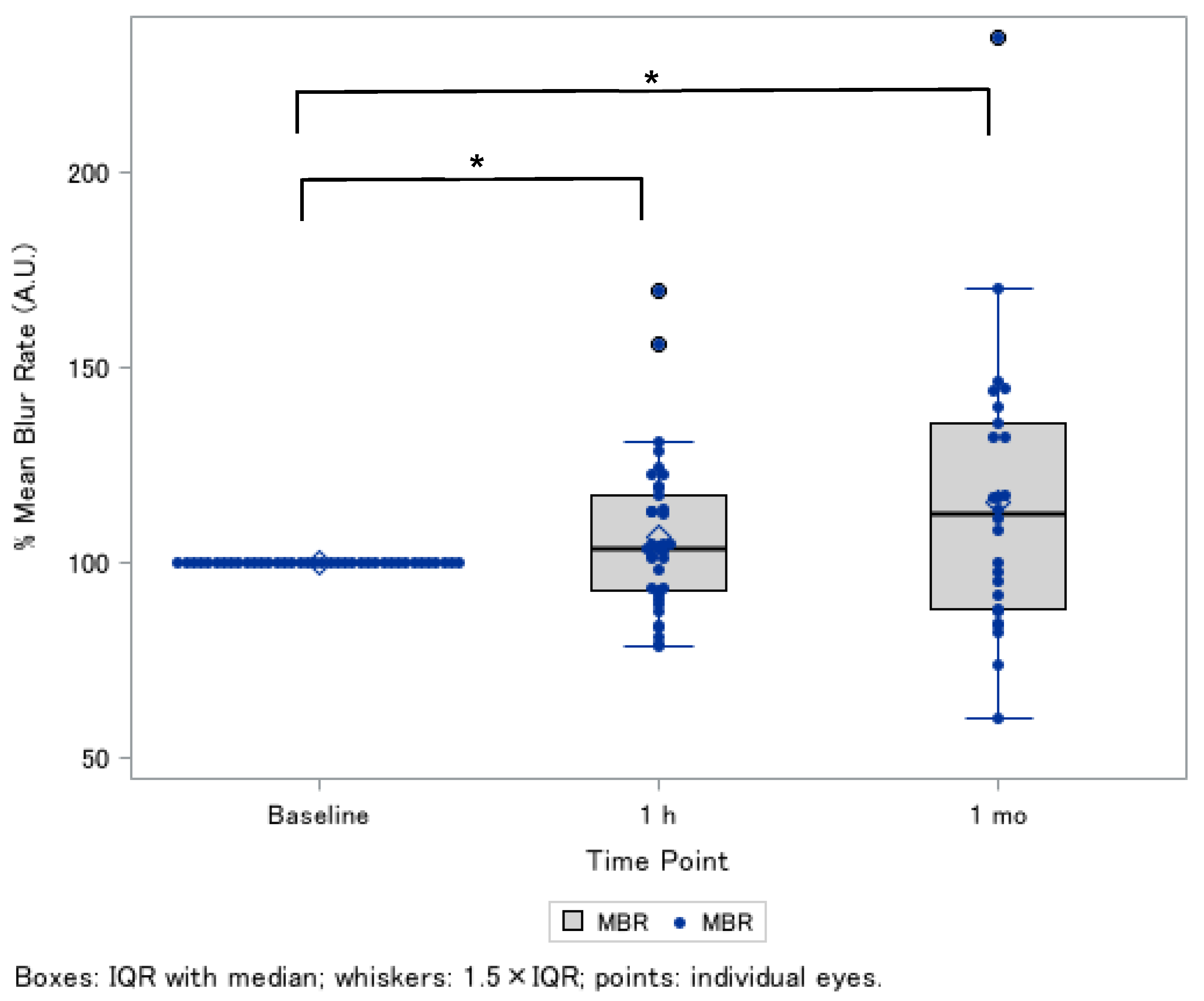

3.2. ONH Blood Flow After the Supplement Intake

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cpRNFLT | Circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| ET-1 | Endothelin-1 |

| HTG | High-tension glaucoma |

| IOP | Intraocular pressure |

| LSFG | Laser speckle flowgraphy |

| MBR | Mean blur rate |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NTG | Normal-tension glaucoma |

| OAG | Open-angle glaucoma |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| ONH | Optic nerve head |

| POAG | Primary open-angle glaucoma |

| RGC | Retinal ganglion cell |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SITA | Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm |

References

- Tham, Y.-C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.-Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B.; Aung, T.; Bourne, R.R.; Bron, A.M.; Ritch, R.; Panda-Jonas, S. Glaucoma. Lancet 2017, 390, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiuchi, Y.; Inoue, T.; Shoji, N.; Nakamura, M.; Tanito, M. The Japan Glaucoma Society guidelines for glaucoma 5th edition. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 67, 189–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. The effectiveness of intraocular pressure reduction in the treatment of normal-tension glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 126, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, A.; Drago, F.; Govoni, S. Protecting the retinal neurons from glaucoma: Lowering ocular pressure is not enough. Pharmacol. Res. 2012, 66, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omodaka, K.; Kikawa, T.; Kabakura, S.; Himori, N.; Tsuda, S.; Ninomiya, T.; Takahashi, N.; Pak, K.; Takeda, N.; Akiba, M.; et al. Clinical characteristics of glaucoma patients with various risk factors. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022, 22, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.C.; Ervin, A.-M.; Tao, J.; Davis, R.M. Antioxidant vitamin supplementation for preventing and slowing the progression of age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 6, CD004567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, S.E.; Loprinzi, P.D. Influence of flavonoid-rich fruit and vegetable intake on diabetic retinopathy and diabetes-related biomarkers. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2014, 28, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Willett, W.C.; Rosner, B.A.; Buys, E.; Wiggs, J.L.; Pasquale, L.R. Association of Dietary Nitrate Intake With Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Prospective Analysis From the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergroesen, J.E.; de Crom, T.O.E.; van Duijn, C.M.; Voortman, T.; Klaver, C.C.W.; Ramdas, W.D. MIND diet lowers risk of open-angle glaucoma: The Rotterdam Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, P.; Kase, Y.; Ishige, A.; Sasaki, H.; Kurosawa, S.; Nakamura, T. The herbal medicine Dai-kenchu-to and one of its active components [6]-shogaol increase intestinal blood flow in rats. Life Sci. 2002, 70, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, T.; Kaneko, A.; Omiya, Y.; Ohbuchi, K.; Ohno, N.; Yamamoto, M. Epithelial transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1)-dependent adrenomedullin upregulates blood flow in rat small intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013, 304, G428–G436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Sato, K.; Kiyota, N.; Tsuda, S.; Murayama, N.; Nakazawa, T. A ginger extract improves ocular blood flow in rats with endothelin-induced retinal blood flow dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Siesky, B.; Huang, A.; Do, T.; Mathew, S.; Frantz, R.; Gross, J.; Januleviciene, I.; Vercellin, A.C.V. Lutein Complex Supplementation Increases Ocular Blood Flow Biomarkers in Healthy Subjects. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. Int. Z. Vitamin-und Ernahrungsforschung. J. Int. Vitaminol. Nutr. 2019, 89, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidl, D.; Howorka, K.; Szegedi, S.; Stjepanek, K.; Puchner, S.; Bata, A.; Scheschy, U.; Aschinger, G.; Werkmeister, R.M.; Schmetterer, L.; et al. A pilot study to assess the effect of a three-month vitamin supplementation containing L-methylfolate on systemic homocysteine plasma concentrations and retinal blood flow in patients with diabetes. Mol. Vis. 2020, 26, 326–333. [Google Scholar]

- Organisciak, D.; Wong, P.; Rapp, C.; Darrow, R.; Ziesel, A.; Rangarajan, R.; Lang, J. Light-induced retinal degeneration is prevented by zinc, a component in the age-related eye disease study formulation. Photochem. Photobiol. 2012, 88, 1396–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyota, N.; Shiga, Y.; Omodaka, K.; Pak, K.; Nakazawa, T. Time-Course Changes in Optic Nerve Head Blood Flow and Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in Eyes with Open-angle Glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyota, N.; Shiga, Y.; Omodaka, K.; Pak, K.; Nakazawa, T. Progression in Open-Angle Glaucoma with Myopic Disc and Blood Flow in the Optic Nerve Head and Peripapillary Chorioretinal Atrophy Zone. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2020, 3, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.L.; Green, J.; Lewis, B. Lutein and zeaxanthin in eye and skin health. Clin. Dermatol. 2009, 27, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vessani, R.M.; Ritch, R.; Liebmann, J.M.; Jofe, M. Plasma homocysteine is elevated in patients with exfoliation syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 136, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaconi, J.A.; Yu, F.; Stone, K.L.; Pedula, K.L.; Ensrud, K.E.; Cauley, J.A.; Hochberg, M.C.; Coleman, A.L. The association of consumption of fruits/vegetables with decreased risk of glaucoma among older African-American women in the study of osteoporotic fractures. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 154, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.A.; Harder, J.M.; Foxworth, N.E.; Cochran, K.E.; Philip, V.M.; Porciatti, V.; Smithies, O.; John, S.W.M. Vitamin B3 modulates mitochondrial vulnerability and prevents glaucoma in aged mice. Science 2017, 355, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyota, N.; Shiga, Y.; Yasuda, M.; Aizawa, N.; Omodaka, K.; Tsuda, S.; Pak, K.; Kunikata, H.; Nakazawa, T. The optic nerve head vasoreactive response to systemic hyperoxia and visual field defect progression in open-angle glaucoma, a pilot study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020, 98, e747–e753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Kiyota, N.; Yoshida, M.; Omodaka, K.; Nakazawa, T. The Relationship Between Kiritsu-Meijin-Derived Autonomic Function Parameters and Visual-Field Defects in Eyes with Open-Angle Glaucoma. Curr. Eye Res. 2023, 48, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, J.; Konieczka, K.; Flammer, A.J. The primary vascular dysregulation syndrome: Implications for eye diseases. EPMA J. 2013, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, S.; Shiga, Y.; Kokubun, T.; Konno, H.; Himori, N.; Ryu, M.; Numata, T.; Kaneko, S.; Kuroda, H.; Tanaka, J.; et al. The traditional kampo medicine tokishakuyakusan increases ocular blood flow in healthy subjects. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014, 2014, 586857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, A.; Shiga, Y.; Takayama, S.; Arita, R.; Maekawa, S.; Kaneko, S.; Himori, N.; Ishii, T.; Nakazawa, T. Traditional medicine as a potential treatment for Flammer syndrome. EPMA J. 2017, 8, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickla, D.L.; Wallman, J. The multifunctional choroid. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2010, 29, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, T.; Zhu, D.; Bi, H.S.; Jonas, J.B.; Jonas, R.A.; Nagaoka, N.; Moriyama, M.; Yoshida, T.; Ohno-Matsui, K. Parapapillary Diffuse Choroidal Atrophy in Children Is Associated with Extreme Thinning of Parapapillary Choroid. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boote, C.; Sigal, I.A.; Grytz, R.; Hua, Y.; Nguyen, T.D.; Girard, M.J.A. Scleral structure and biomechanics. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 74, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Xu, L.; Bin Wei, W.; Pan, Z.; Yang, H.; Holbach, L.; Panda-Jonas, S.; Wang, Y.X. Retinal Thickness and Axial Length. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, N.; Kunikata, H.; Shiga, Y.; Yokoyama, Y.; Omodaka, K.; Nakazawa, T. Correlation between structure/function and optic disc microcirculation in myopic glaucoma, measured with laser speckle flowgraphy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-I.; Su, F.-Y.; Ho, H.-C.; Chen, Y.-W.; Lee, C.-K.; Lai, F.; Lu, H.H.-S.; Ko, M.-L. Axial length, more than aging, decreases the thickness and superficial vessel density of retinal nerve fiber layer in non-glaucomatous eyes. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossniklaus, H.E.; Nickerson, J.M.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Bergman, L.A.M.K.; Berglin, L. Anatomic alterations in aging and age-related diseases of the eye. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, ORSF23–ORSF27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Han, Z.; Zeng, L.; Chen, H. The Impact of Aging on Ocular Diseases: Unveiling Complex Interactions. Aging Dis. 2024, 16, 2803–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaster, J.H. Age-related arterial dysfunction in the brain may precede Parkinson’s disease and other types of dementia, reflecting a failure to release gravitational ischemia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2024, 327, H000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer, A.R.; Bourourou, M.; Lesage, F.; Hamel, E. Neurovascular coupling and functional connectivity changes through the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum: Effects of simvastatin treatment. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, L.K.; Friso, S.; Choi, S.-W. Nutritional influences on epigenetics and age-related disease. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2012, 71, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Features of Included Subjects (Total 19 Patients) | |

| Age, mean (SD), year | 60.2 (9.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 10 (52.6) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 122.8 (18.0) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 70.3 (14.3) |

| Pulse rate, mean (SD), bpm | 66.3 (9.2) |

| Number of glaucoma eye drops, mean (SD) | 4.3 (0.9) |

| Clinical features of eyes with glaucoma (total 38 eyes) | |

| Types of glaucoma | |

| High-tension glaucoma (≥21 mm Hg), n (%) | 11 (28.9) |

| Normal-tension glaucoma (<21 mmHg), n (%) | 20 (52.6) |

| Steroid-induced glaucoma, n (%) | 7 (18.4) |

| Intraocular pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 11.8 (3.7) |

| Axial length, mean (SD), mm | 25.9 (1.7) |

| Mean deviation, mean (SD), dB | −14.0 (8.7) |

| Circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness, mean (SD), µm | 66.4 (16.4) |

| Ganglion cell complex layer, mean (SD), µm | 75.1 (12.9) |

| Ocular perfusion pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 46.7 (9.9) |

| Mean blur rate, mean (SD), AU | 7.8 (2.9) |

| Relative MBR ¶, % (Tissue-Area MBR, AU) | Post-1 h (n = 38 Eyes) | Post-1 Month (n = 26 Eyes) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, sex-adjusted (Model 1) | 106.9 ± 3.1 * | 115.4 ± 6.7 * |

| Model 1 + axial length-adjusted | 106.9 ± 3.1 * | 115.4 ± 6.7 * |

| Model 1 + axial length, MAP, IOP-adjusted | 107.0 ± 3.0 * | 114.9 ± 6.7 * |

| Demographic Features of Included Subjects (Total 19 Patients) | ONH Blood Flow (Up) | ONH Blood Flow (Down) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), year | 61.5 (8.7) | 57.8 (9.3) | 0.24 |

| Male, n (%) | 6 (15.8) | 4 (10.5) | 0.50 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 123.1 (18.3) | 123.2 (18.7) | 0.99 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 69.5 (16.0) | 71.9 (11.6) | 0.63 |

| Pulse rate, mean (SD), bpm | 65.8 (10.1) | 67.5 (7.9) | 0.62 |

| Number of glaucoma eye drops, mean (SD) | 4.1 (0.9) | 3.8 (0.8) | 0.39 |

| Clinical features of eyes with glaucoma (total 38 eyes) | |||

| Types of glaucoma | 0.85 | ||

| High-tension glaucoma (≥21 mm Hg), n (%) | 14 (36.8) | 6 (15.8) | |

| Normal-tension glaucoma (<21 mmHg), n (%) | 7 (18.4) | 4 (10.5) | |

| Steroid-induced glaucoma, n (%) | 4 (10.5) | 3 (7.8) | |

| Intraocular pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 12.3 (0.7) | 11.2 (1.1) | 0.36 |

| Axial length, mean (SD), mm | 25.4 (1.4) | 27.0 (1.8) | 0.006 |

| Mean deviation, mean (SD), dB | −13.6 (8.7) | −13.4 (8.2) | 0.96 |

| Circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness, mean (SD), µm | 65.6 (14.8) | 69.5 (19.0) | 0.49 |

| Ganglion cell complex layer, mean (SD), µm | 75.0 (12.5) | 76.7 (13.6) | 0.72 |

| Ocular perfusion pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 45.9 (10.3) | 48.2 (9.7) | 0.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hanyuda, A.; Tsuda, S.; Takahashi, N.; Takahashi, N.; Sato, K.; Nakazawa, T. Effects of a Red-Ginger-Based Multi-Nutrient Supplement on Optic Nerve Head Blood Flow in Open-Angle Glaucoma. Nutrients 2026, 18, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010140

Hanyuda A, Tsuda S, Takahashi N, Takahashi N, Sato K, Nakazawa T. Effects of a Red-Ginger-Based Multi-Nutrient Supplement on Optic Nerve Head Blood Flow in Open-Angle Glaucoma. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010140

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanyuda, Akiko, Satoru Tsuda, Nana Takahashi, Naoki Takahashi, Kota Sato, and Toru Nakazawa. 2026. "Effects of a Red-Ginger-Based Multi-Nutrient Supplement on Optic Nerve Head Blood Flow in Open-Angle Glaucoma" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010140

APA StyleHanyuda, A., Tsuda, S., Takahashi, N., Takahashi, N., Sato, K., & Nakazawa, T. (2026). Effects of a Red-Ginger-Based Multi-Nutrient Supplement on Optic Nerve Head Blood Flow in Open-Angle Glaucoma. Nutrients, 18(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010140