Targeting Uterine Quiescence: A Multitarget Strategy with Vitamin D, High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid, Magnesium, and Palmitoylethanolamide to Prevent Preterm Birth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- In vitro research: molecular pathways (such as NF-κB, cytokine expression, and contractile protein expression) are reported using cell culture models (such as myometrial smooth muscle cells, amniotic cells, and immune cells).

- Animal studies: in vivo models (such as rat models of inflammation-induced preterm birth) assessing the target molecules’ effectiveness in lowering inflammatory indicators or preventing premature delivery.

- Clinical studies: human studies that report on pregnancy outcomes (e.g., preterm birth, uterine contractions, cervical length, subchorionic hematoma resorption) or pertinent biomarkers (e.g., plasma cytokine levels) include randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective/retrospective cohort studies, and case-control studies.

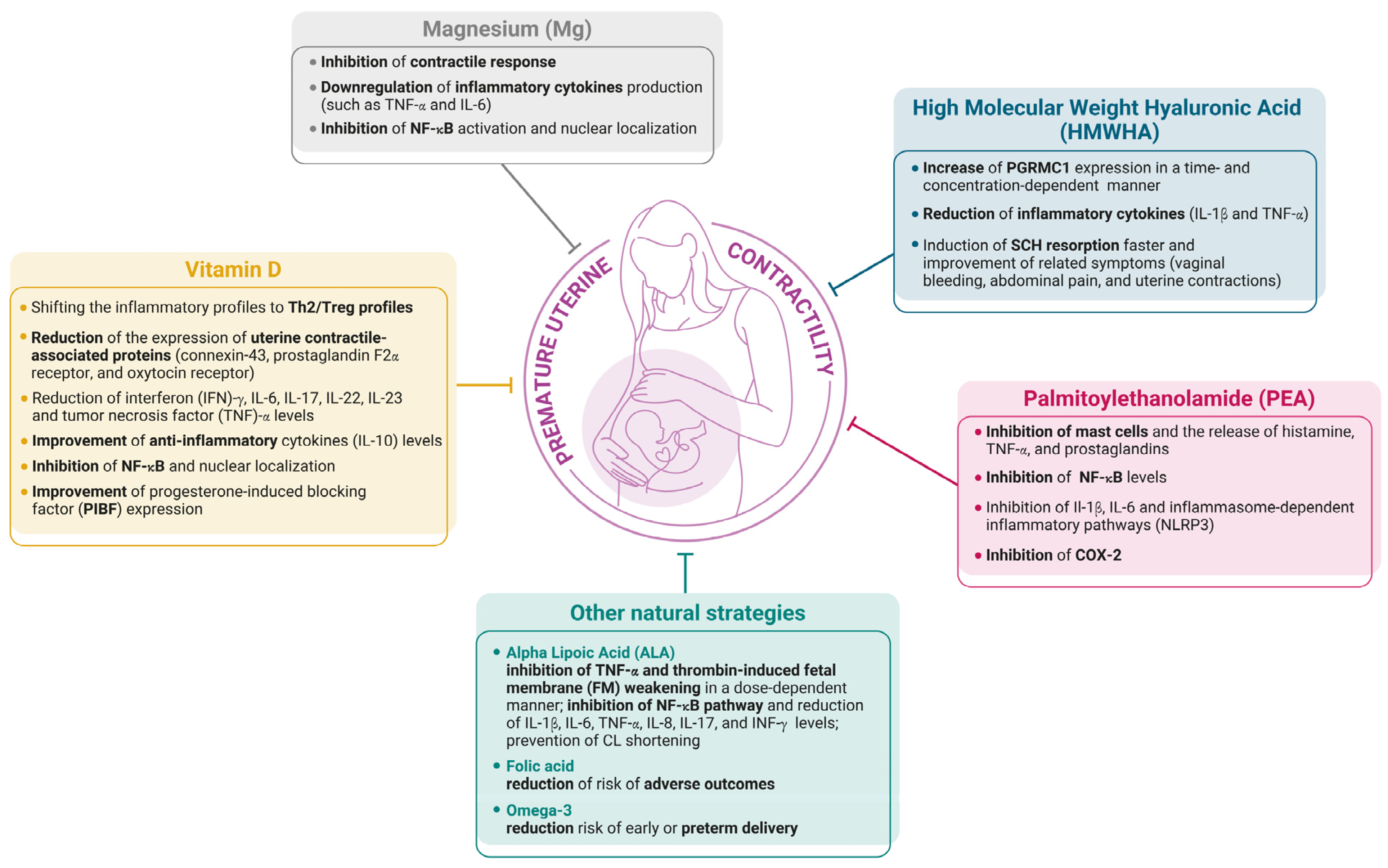

3. Natural Molecules for Preventing Premature Contractility

3.1. Vitamin D

3.2. High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid (HMWHA)

3.3. Magnesium (Mg)

3.4. Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA)

3.5. Other Natural Strategies

3.5.1. Alpha Lipoic Acid

3.5.2. Vitamin B9 Folic Acid

3.5.3. Omega-3

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEA | anandamide |

| ALA | alpha lipoic acid |

| CL | cervical length |

| COX-2 | cyclooxygensae-2 |

| CRH | corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| CX-43 | connexin 43 |

| FOXP3 | forkhead box 3 |

| GLP | good laboratory practice |

| HCA | histological chorioamnionitis |

| HUVECs | human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| IFN-γ | interferon gamma |

| IL-1β | interleukin 1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin 6 |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MC | mast cells |

| MgSO4 | magnesium sulfate |

| MMP-9 | matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| NAE | N-acyl-ethanolamine |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-kappa B |

| NK | natural killer |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| PGF2 | prostaglandins |

| PGRMC1 | progesterone receptor membrane component 1 |

| PHA | phytohemagglutinin |

| PIBF | progesterone-induced blocking factor |

| POI | primary ovarian insufficiency |

| PPAR-α | proliferator-activated receptor |

| PPROM | preterm premature rupture of membranes |

| PTB | preterm birth |

| RCTs | randomized controlled trials |

| SCH | subchorionic hematoma resorption |

| TLRs | toll-like receptors |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor |

| Treg | T-regulatory |

| TRPV1 | vanilloid receptor 1 |

| VSMCs | vascular smooth muscle cells |

References

- Iams, J.D.; Newman, R.B.; Thom, E.A.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Mueller-Heubach, E.; Moawad, A.; Sibai, B.M.; Caritis, S.N.; Miodovnik, M.; Paul, R.H.; et al. Frequency of uterine contractions and the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokou, R.; Lianou, A.; Lampridou, M.; Panagiotounakou, P.; Kafalidis, G.; Paliatsiou, S.; Volaki, P.; Tsantes, A.G.; Boutsikou, T.; Iliodromiti, Z.; et al. Neonates at Risk: Understanding the Impact of High-Risk Pregnancies on Neonatal Health. Medicina 2025, 61, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohuma, E.O.; Moller, A.B.; Bradley, E.; Chakwera, S.; Hussain-Alkhateeb, L.; Lewin, A.; Okwaraji, Y.B.; Mahanani, W.R.; Johansson, E.W.; Lavin, T.; et al. National, regional, and global estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: A systematic analy-sis. Lancet 2023, 402, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vause, S.; Johnston, T. Management of preterm labour. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000, 83, F79–F85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoldrick, E.; Stewart, F.; Parker, R.; Dalziel, S.R. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020, 12, CD004454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Yeo, L.; Miranda, J.; Hassan, S.S.; Conde-Agudelo, A.; Chaiworapongsa, T. A blueprint for the prevention of preterm birth: Vaginal progesterone in women with a short cervix. J. Perinat. Med. 2013, 41, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrowsmith, S.; Kendrick, A.; Wray, S. Drugs acting on the pregnant uterus. Obstet. Gynaecol. Reprod. Med. 2010, 20, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, V.L.; Farmer, R.M. Controversies in tocolytic therapy. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 42, 802–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingemarsson, I.; Lamont, R.F. An update on the controversies of tocolytic therapy for the prevention of preterm birth. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2003, 82, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Conde-Agudelo, A.; Da Fonseca, E.; O’Brien, J.M.; Cetingoz, E.; Creasy, G.W.; Hassan, S.S.; Nicolaides, K.H. Vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm birth and adverse perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations with a short cervix: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.E.; Marlow, N.; Messow, C.M.; Shennan, A.; Bennett, P.R.; Thornton, S.; Robson, S.C.; McConnachie, A.; Petrou, S.; Sebire, N.J.; et al. Vaginal progesterone prophylaxis for preterm birth (the OPPTIMUM study): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 2106–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facchinetti, F.; Vergani, P.; Di Tommaso, M.; Marozio, L.; Acaia, B.; Vicini, R.; Pignatti, L.; Locatelli, A.; Spitaleri, M.; Benedetto, C.; et al. Progestogens for Maintenance Tocolysis in Women With a Short Cervix: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 130, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shynlova, O.; Nadeem, L.; Lye, S. Progesterone control of myometrial contractility. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 234, 106397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leimert, K.B.; Xu, W.; Princ, M.M.; Chemtob, S.; Olson, D.M. Inflammatory Amplification: A Central Tenet of Uterine Transition for Labor. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 660983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimert, K.B.; Messer, A.; Gray, T.; Fang, X.; Chemtob, S.; Olson, D.M. Maternal and fetal intrauterine tissue crosstalk promotes proinflammatory amplification and uterine transition†. Biol. Reprod. 2019, 100, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a001651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; MacIntyre, D.A.; Lee, Y.S.; Khanjani, S.; Terzidou, V.; Teoh, T.G.; Bennett, P.R. Nuclear factor kappa B activation occurs in the amnion prior to labour onset and modulates the expression of numerous labour associated genes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, T.M.; Bennett, P.R. The role of nuclear factor kappa B in human labour. Reproduction 2005, 130, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Mazor, M.; Brandt, F.; Sepulveda, W.; Avila, C.; Cotton, D.B.; Dinarello, C.A. Interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 beta in preterm and term human parturition. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1992, 27, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Parvizi, S.T.; Oyarzun, E.; Mazor, M.; Wu, Y.K.; Avila, C.; Athanassiadis, A.P.; Mitchell, M.D. Amniotic fluid interleukin-1 in spontaneous labor at term. J. Reprod. Med. 1990, 35, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, R.; Durum, S.; Dinarello, C.A.; Oyarzun, E.; Hobbins, J.C.; Mitchell, M.D. Interleukin-1 stimulates prostaglandin biosynthesis by human amnion. Prostaglandins 1989, 37, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchner, K.; Iavazzo, C.; Gourgiotis, D.; Boutsikou, M.; Baka, S.; Hassiakos, D.; Kouskouni, E.; Economou, E.; Malamitsi-Puchner, A.; Creatsas, G. Mid-trimester amniotic fluid interleukins (IL-1β, IL-10 and IL-18) as possible predictors of preterm delivery. In Vivo 2011, 25, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Osman, I.; Young, A.; Ledingham, M.A.; Thomson, A.J.; Jordan, F.; Greer, I.A.; Norman, J.E. Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 9, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, M.; Chauhan, M.; Awasthi, S. Interplay of cytokines in preterm birth. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2017, 146, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenstrom, K.D.; Andrews, W.W.; Hauth, J.C.; Goldenberg, R.L.; DuBard, M.B.; Cliver, S.P. Elevated second-trimester amniotic fluid interleukin-6 levels predict preterm delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 178, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goepfert, A.R.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Andrews, W.W.; Hauth, J.C.; Mercer, B.; Iams, J.; Meis, P.; Moawad, A.; Thom, E.; VanDorsten, J.P.; et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: Association between cervical interleukin 6 concentration and spontaneous preterm birth. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 184, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, S.L.; Garbose, R.A.; Kim, K.; Kissell, K.; Kuhr, D.L.; Omosigho, U.R.; Perkins, N.J.; Galai, N.; Silver, R.M.; Sjaarda, L.A.; et al. Association of preconception serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with livebirth and pregnancy loss: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Yan, X.T.; Bai, C.M.; Zhang, X.W.; Hui, L.Y.; Yu, X.W. Decreased serum vitamin D levels in early spontaneous pregnancy loss. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1004–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wu, H.M.; Hang, F.; Zhang, Y.S.; Li, M.J. Women with recurrent spontaneous abortion have decreased 25(OH) vitamin D and VDR at the fetal-maternal interface. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2017, 50, e6527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, M.; Foroozanfard, F.; Amini, F.; Sehat, M. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Unexplained Recurrent Spontaneous Abortion: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial Glob. J. Health Sci. 2017, 9, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monastra, G.; De Grazia, S.; De Luca, L.; Vittorio, S.; Unfer, V. Vitamin D: A steroid hormone with progesterone-like activity. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 2502–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerchbaum, E.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B. Vitamin D and fertility: A systematic review. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 166, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghupathy, R.; Al-Mutawa, E.; Al-Azemi, M.; Makhseed, M.; Azizieh, F.; Szekeres-Bartho, J. Progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF) modulates cytokine production by lymphocytes from women with recurrent miscarriage or preterm delivery. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2009, 80, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, Z.; Laskarin, G.; Rukavina, D.; Szekeres-Bartho, J. Progesterone-induced blocking factor inhibits degranulation of natural killer cells. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1999, 42, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polgár, B.; Nagy, E.; Mikó, E.; Varga, P.; Szekeres-Barthó, J. Urinary progesterone-induced blocking factor concentration is related to pregnancy outcome. Biol. Reprod. 2004, 71, 1699–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Tian, J.; Liu, L.; Dong, Y.; Mao, T. Expression of kisspeptin/GPR54 and PIBF/PR in the first trimester trophoblast and decidua of women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2014, 210, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekeres-Barthó, J.; Miko, E.; Balassa, T.; Unfer, V. Immunomodulatory Activity of Vitamin D. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, S303. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, V.R.; Romao-Veiga, M.; Nunes, P.R.; de Oliveira, L.R.C.; Romagnoli, G.G.; Peracoli, J.C.; Peracoli, M.T.S. Immunomodulatory effect of vitamin D on the STATs and transcription factors of CD4(+) T cell subsets in pregnant women with preeclampsia. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 234, 108917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.R.; Iwata, M.; von Andrian, U.H. Vitamin effects on the immune system: Vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.S.; Choi, M.Y.; Longtine, M.S.; Nelson, D.M. Vitamin D effects on pregnancy and the placenta. Placenta 2010, 31, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thota, C.; Laknaur, A.; Farmer, T.; Ladson, G.; Al-Hendy, A.; Ismail, N. Vitamin D regulates contractile profile in human uterine myometrial cells via NF-κB pathway. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 347.e341–347.e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D.M.; Ammann, C. Role of the prostaglandins in labour and prostaglandin receptor inhibitors in the prevention of preterm labour. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12, 1329–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cruz Ithier, M.; Parobchak, N.; Yadava, S.M.; Schulkin, J.; Rosen, T. Vitamin D stimulates multiple microRNAs to inhibit CRH and other pro-labor genes in human placenta. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 7, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thota, C.; Farmer, T.; Garfield, R.E.; Menon, R.; Al-Hendy, A. Vitamin D elicits anti-inflammatory response, inhibits contractile-associated proteins, and modulates Toll-like receptors in human myometrial cells. Reprod. Sci. 2013, 20, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Hariharan, C.; Bhaumik, D. Role of vitamin D in reducing the risk of preterm labour. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 4, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tous, M.; Villalobos, M.; Iglesias-Vázquez, L.; Fernández-Barrés, S.; Arija, V. Vitamin D status during pregnancy and offspring outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.S.; Tao, Y.H.; Huang, K.; Zhu, B.B.; Tao, F.B. Vitamin D and risk of preterm birth: Up-to-date meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2017, 43, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.L.; Lu, F.G.; Yang, S.H.; Xu, H.L.; Luo, B.A. Does Maternal Vitamin D Deficiency Increase the Risk of Preterm Birth: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2016, 8, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghib, K.; Ghanm, T.I.; Abunamoos, A.; Rajabi, M.; Moawad, S.M.; Mohsen, A.; Kasem, S.; Elsayed, K.; Sayed, M.; Dawoud, A.I.; et al. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation on the incidence of preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, E.; Colannino, G.; Bilotta, G.; Espinola, M.S.B.; Proietti, S.; Oliva, M.M.; Neri, I.; Aragona, C.; Unfer, V. Effect of Oral High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid (HMWHA), Alpha Lipoic Acid (ALA), Magnesium, Vitamin B6 and Vitamin D Supplementation in Pregnant Women: A Retrospective Observational Pilot Study. Clin. Pract. 2023, 13, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcaro, G.; Laganà, A.S.; Neri, I.; Aragona, C. The Association of High-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronic Acid (HMWHA), Alpha Lipoic Acid (ALA), Magnesium, Vitamin B6, and Vitamin D Improves Subchorionic Hematoma Resorption in Women with Threatened Miscarriage: A Pilot Clinical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unfer, V.; Tilotta, M.; Kaya, C.; Noventa, M.; Török, P.; Alkatout, I.; Gitas, G.; Bilotta, G.; Laganà, A.S. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of hyaluronic acid during pregnancy: A matter of molecular weight. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2021, 17, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Zhou, X.; Fang, T.; Hou, Y.; Hu, Y. Hyaluronic acid promotes the expression of progesterone receptor membrane component 1 via epigenetic silencing of miR-139-5p in human and rat granulosa cells. Biol. Reprod. 2014, 91, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gellersen, B.; Fernandes, M.S.; Brosens, J.J. Non-genomic progesterone actions in female reproduction. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2009, 15, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, H.J.; Ahmed, I.S.; Twist, K.E.; Craven, R.J. PGRMC1 (progesterone receptor membrane component 1): A targetable protein with multiple functions in steroid signaling, P450 activation and drug binding. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 121, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Shi, S.Q.; Huang, H.J.; Balducci, J.; Garfield, R.E. Changes in PGRMC1, a potential progesterone receptor, in human myometrium during pregnancy and labour at term and preterm. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 17, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.R.; Choi, H.E.; Jo, E.; Choi, H.Y.; Jung, S.; Jang, S.; Choi, S.J.; Hwang, S.O. Decreased expression of progesterone receptor membrane component 1 in fetal membranes with chorioamnionitis among women with preterm birth. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouladi-Nashta, A.A.; Raheem, K.A.; Marei, W.F.; Ghafari, F.; Hartshorne, G.M. Regulation and roles of the hyaluronan system in mammalian reproduction. Reproduction 2017, 153, R43–R58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgul, Y.; Holt, R.; Mummert, M.; Word, A.; Mahendroo, M. Dynamic changes in cervical glycosaminoglycan composition during normal pregnancy and preterm birth. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3493–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, S.L.; Kyme, P.; Tseng, C.W.; Soliman, A.; Kaplan, A.; Liang, J.; Nizet, V.; Jiang, D.; Murali, R.; Arditi, M.; et al. Group B Streptococcus Evades Host Immunity by Degrading Hyaluronan. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.M.; Park, S.J.; Noh, I.; Kim, C.H. The effects of the molecular weights of hyaluronic acid on the immune responses. Biomater. Res. 2021, 25, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agier, J.; Żelechowska, P.; Kozłowska, E.; Brzezińska-Błaszczyk, E. Expression of surface and intracellular Toll-like receptors by mature mast cells. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016, 41, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilaker Micili, S.; Tarı, O.; Neri, I.; Proietti, S.; Unfer, V. Does high molecular weight-hyaluronic acid prevent hormone-induced preterm labor in rats? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 3022–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Cil, O. Magnesium for disease treatment and prevention: Emerging mechanisms and opportunities. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 45, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.G.; McGaughey, H.S., Jr.; Corey, E.L.; Thornton, W.N., Jr. The effects of magnesium therapy on the duration of labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1959, 78, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairoz; Prabhu, K.; Dastidar, R.G.; Aroor, A.R.; Rao, M.; Shetty, S.; Poojari, V.G.; Bs, V. Micronutrients in Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. F1000Research 2022, 11, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Wright, C. Safety and efficacy of supplements in pregnancy. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, L.M.; DM, N.F.; Gaydadzhieva, G.T.; Mazurkiewicz, O.M.; Leeson, H.; Wright, C.P. Magnesium in pregnancy. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarean, E.; Tarjan, A. Effect of Magnesium Supplement on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Randomized Control Trial. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2017, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomin, V.P.; Gibbs, S.G.; Vanam, R.; Morimiya, A.; Hurd, W.W. Effect of magnesium sulfate on contractile force and intracellular calcium concentration in pregnant human myometrium. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1384–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, J.; Romani, A.M.; Valentin-Torres, A.M.; Luciano, A.A.; Ramirez Kitchen, C.M.; Funderburg, N.; Mesiano, S.; Bernstein, H.B. Magnesium decreases inflammatory cytokine production: A novel innate immunomodulatory mechanism. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 6338–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlach, J.; Pagès, N.; Bac, P.; Bara, M.; Guiet-Bara, A. New data on the importance of gestational Mg deficiency. Magnes. Res. 2004, 17, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, P.; Hill, M.; Bogoda, N.; Subah, S.; Venkatesh, R. Palmitoylethanolamide: A Natural Compound for Health Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nau, R.; Ribes, S.; Djukic, M.; Eiffert, H. Strategies to increase the activity of microglia as efficient protectors of the brain against infections. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, F.; Romano, B.; Petrosino, S.; Pagano, E.; Capasso, R.; Coppola, D.; Battista, G.; Orlando, P.; Di Marzo, V.; Izzo, A.A. Palmitoylethanolamide, a naturally occurring lipid, is an orally effective intestinal anti-inflammatory agent. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosino, S.; Di Marzo, V. The pharmacology of palmitoylethanolamide and first data on the therapeutic efficacy of some of its new formulations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1349–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaj, M.; Saghazadeh, A.; Shirazi, E.; Shalbafan, M.R.; Alavi, K.; Shooshtari, M.H.; Laksari, F.Y.; Hosseini, M.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Akhondzadeh, S. Palmitoylethanolamide as adjunctive therapy for autism: Efficacy and safety results from a randomized controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 103, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotini, S.; Schievano, C.; Guidi, L. Ultra-micronized Palmitoylethanolamide: An Efficacious Adjuvant Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2017, 16, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caltagirone, C.; Cisari, C.; Schievano, C.; Di Paola, R.; Cordaro, M.; Bruschetta, G.; Esposito, E.; Cuzzocrea, S. Co-ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide/Luteolin in the Treatment of Cerebral Ischemia: From Rodent to Man. Stroke Res. 2016, 7, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoletto, R.; Comacchio, C.; Garzitto, M.; Piscitelli, F.; Balestrieri, M.; Colizzi, M. Palmitoylethanolamide supplementation for human health: A state-of-the-art systematic review of Randomized Controlled Trials in patient populations. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2025, 43, 100927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachkangi, P.; Taylor, A.H.; Bari, M.; Maccarrone, M.; Konje, J.C. Prediction of preterm labour from a single blood test: The role of the endocannabinoid system in predicting preterm birth in high-risk women. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 243, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agostino, G.; La Rana, G.; Russo, R.; Sasso, O.; Iacono, A.; Esposito, E.; Mattace Raso, G.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Loverme, J.; Piomelli, D.; et al. Central administration of palmitoylethanolamide reduces hyperalgesia in mice via inhibition of NF-kappaB nuclear signalling in dorsal root ganglia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 613, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Paola, R.; Fusco, R.; Gugliandolo, E.; Crupi, R.; Evangelista, M.; Granese, R.; Cuzzocrea, S. Co-Micronized Palmitoylethanolamide/Polydatin Treatment Causes Endometriotic Lesion Regression in a Rodent Model of Surgically Induced Endometriosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motomura, K.; Romero, R.; Galaz, J.; Tao, L.; Garcia-Flores, V.; Xu, Y.; Done, B.; Arenas-Hernandez, M.; Miller, D.; Gutierrez-Contreras, P.; et al. Fetal and maternal NLRP3 signaling is required for preterm labor and birth. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e158238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Capoccia, E.; Turco, F.; Palumbo, I.; Lu, J.; Steardo, A.; Cuomo, R.; Sarnelli, G.; Steardo, L. Palmitoylethanolamide improves colon inflammation through an enteric glia/toll like receptor 4-dependent PPAR-α activation. Gut 2014, 63, 1300–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsson, L.; Gouveia-Figueira, S.; Häggström, J.; Alhouayek, M.; Fowler, C.J. The anti-inflammatory compound palmitoylethanolamide inhibits prostaglandin and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid production by a macrophage cell line. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2017, 5, e00300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svobodova, A.; Vrkoslav, V.; Smeringaiova, I.; Jirsova, K. Distribution of an analgesic palmitoylethanolamide and other N-acylethanolamines in human placental membranes. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuel, H.; Burkman, L.J.; Lippes, J.; Crickard, K.; Forester, E.; Piomelli, D.; Giuffrida, A. N-Acylethanolamines in human reproductive fluids. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2002, 121, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, M.I.; Rojas, I.G.; Penissi, A.B. Uterine mast cells: A new hypothesis to understand how we are born. Biocell 2004, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, F.M.; Shepherd, M.C.; Nibbs, R.J.; Nelson, S.M. The role of mast cells and their mediators in reproduction, pregnancy and labour. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2011, 17, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woidacki, K.; Zenclussen, A.C.; Siebenhaar, F. Mast cell-mediated and associated disorders in pregnancy: A risky game with an uncertain outcome? Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiadi, M.; Kempuraj, D.; Boucher, W.; Kalogeromitros, D.; Theoharides, T.C. Progesterone inhibits mast cell secretion. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2006, 19, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bytautiene, E.; Vedernikov, Y.P.; Saade, G.R.; Romero, R.; Garfield, R.E. Degranulation of uterine mast cell modifies contractility of isolated myometrium from pregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 1705–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloe, L.; Leon, A.; Levi-Montalcini, R. A proposed autacoid mechanism controlling mastocyte behaviour. Agents Actions 1993, 39, C145–C147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facci, L.; Dal Toso, R.; Romanello, S.; Buriani, A.; Skaper, S.D.; Leon, A. Mast cells express a peripheral cannabinoid receptor with differential sensitivity to anandamide and palmitoylethanolamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 3376–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, S.; Brazis, P.; della Valle, M.F.; Miolo, A.; Puigdemont, A. Effects of palmitoylethanolamide on immunologically induced histamine, PGD2 and TNFalpha release from canine skin mast cells. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2010, 133, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramo, F.; Lazzarini, G.; Pirone, A.; Lenzi, C.; Albertini, S.; Della Valle, M.F.; Schievano, C.; Vannozzi, I.; Miragliotta, V. Ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide counteracts the effects of compound 48/80 in a canine skin organ culture model. Vet. Dermatol 2017, 28, 456–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, N.S.; Gumaste, S.; Subah, S.; Bogoda, N.O. Palmitoylethanolamide: Prenatal Developmental Toxicity Study in Rats. Int. J. Toxicol. 2021, 40, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galla, R.; Mulè, S.; Ferrari, S.; Grigolon, C.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. Palmitoylethanolamide as a Supplement: The Importance of Dose-Dependent Effects for Improving Nervous Tissue Health in an In Vitro Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petca, A.; Bot, M.; Maru, N.; Calo, I.G.; Borislavschi, A.; Dumitrascu, M.C.; Petca, R.C.; Sandru, F.; Zvanca, M.E. Benefits of α-lipoic acid in high-risk pregnancies (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monastra, G.; De Grazia, S.; Cilaker Micili, S.; Goker, A.; Unfer, V. Immunomodulatory activities of alpha lipoic acid with a special focus on its efficacy in preventing miscarriage. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2016, 13, 1695–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Z.; Kampfrath, T.; Sun, Q.; Parthasarathy, S.; Rajagopalan, S. Evidence that α-lipoic acid inhibits NF-κB activation independent of its antioxidant function. Inflamm. Res. 2011, 60, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.J.; Park, K.G.; Kim, Y.N.; Kwon, T.K.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, K.U.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, I.K. Alpha-lipoic acid inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression by inhibiting NF-kappaB transcriptional activity. Exp. Mol. Med. 2007, 39, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcaro, G.; Brillo, E.; Giardina, I.; Di Iorio, R. Alpha Lipoic Acid (ALA) effects on subchorionic hematoma: Preliminary clinical results. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 3426–3432. [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, M.; Guaraldi, C.; Costantino, D. Resolution of subchorionic hematoma and symptoms of threatened miscarriage using vaginal alpha lipoic acid or progesterone: Clinical evidences. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 1656–1663. [Google Scholar]

- Iams, J.D.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Meis, P.J.; Mercer, B.M.; Moawad, A.; Das, A.; Thom, E.; McNellis, D.; Copper, R.L.; Johnson, F.; et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichini, D.; Imbrogno, M.G.; Basile, L.; Monari, F.; Ferrari, F.; Neri, I. Oral supplementation of α-lipoic acid (ALA), magnesium, vitamin B6 and vitamin D stabilizes cervical changes in women presenting risk factors for preterm birth. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 8879–8886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, E.; Colannino, G.; Ferrara, P. Efficacy of magnesium and alpha lipoic acid supplementation in reducing premature uterine contractions. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 4, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Moore, R.M.; Sharma, A.; Mercer, B.M.; Mansour, J.M.; Moore, J.J. In an in-vitro model using human fetal membranes, α-lipoic acid inhibits inflammation induced fetal membrane weakening. Placenta 2018, 68, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Berkay Yılmaz, Y.; Antika, G.; Boyunegmez Tumer, T.; Fawzi Mahomoodally, M.; Lobine, D.; Akram, M.; Riaz, M.; Capanoglu, E.; Sharopov, F.; et al. Insights on the Use of α-Lipoic Acid for Therapeutic Purposes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Regil, L.M.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Fernández-Gaxiola, A.C.; Rayco-Solon, P. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, Cd007950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larqué, E.; Gil-Sánchez, A.; Prieto-Sánchez, M.T.; Koletzko, B. Omega 3 fatty acids, gestation and pregnancy outcomes. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, S77–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Wong, M.; Rogozinska, E.; Thangaratinam, S. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids in prevention of early preterm delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized studies. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 198, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Model and Design | Interventions | Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribeiro, V.R. 2022 | Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) from 40 pregnant women | 100 nM of vitamin D for 24 h | Shifting the inflammatory profiles, to Th2/Treg profiles; decreasing levels of interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, IL-23 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α; increasing levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β | [38] |

| Szekeres-Barthó, J. 2020 | Phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-activated peripheral lymphocytes | Escalating levels of vitamin D and a standard dose of progesterone for 24 h | Increases progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF) expression | [37] |

| Thota, C. 2014 | Uterine myometrial smooth muscle (UtSM) cells | 0, 5, 10, 50, 150, and 300 nmol/L of 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D for 24 h | Inhibition of the expression of uterine contractile-associated proteins (connexin-43, prostaglandin F2α receptor, and oxytocin receptor); inhibition phosphorylation of IkBα and nuclear translocation of NFkB-p65; decrease in the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and -13 and TNFα | [41] |

| Wang, B. 2018 | Placenta from healthy women with estimated gestational age of 38 and 40 weeks | 1 nM, 10 nM, 10 µM of vitamin D for 24 h | Inhibition of CRH (Corticotropin-releasing Hormone) and COX-2 genes by upregulating miR-181 b-5p or miR-26b-5p | [43] |

| Singh, J. 2017; Zhou, S.S. 2017; Moghib, K. 2014 | Pregnant women | Vitamin D supplementation until the end of pregnancy | Reduction in PTB | [45,47,49] |

| Study | Model and Design | Interventions | Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao, G. et al., 2014 | Granulosa cells (in vitro study) | HMWHA (100 μg/mL, 200 μg/mL, and 500 μg/mL) | HMWHA increases PGRMC1 expression in a time- and concentration-dependent manner | [53] |

| Cilaker Micili, S. et al., 2023 | Rats (in vivo study) | Low dose (2.5 mg) and high dose (5 mg) | HMWHA prevents PTB and decreases inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) | [63] |

| Parente, E. et al., 2023 | Pregnant women (clinical study) | HMWHA (200 mg) in association with natural molecules versus control group | HMWHA prevents PTB and other adverse events (pelvic pain, spontaneous contractions, miscarriages, and hospitalization) | [50] |

| Porcaro, G. et al., 2024 | Pregnant women (clinical study) | HMWHA (200 mg) in association with natural molecules in association with vaginal P4 versus control group | HMWHA induces SCH resorption faster and improves related symptoms (vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, and uterine contractions) | [51] |

| Study | Model and Design | Interventions | Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fomin, V.P. 2005 | Pregnant human myometrial strips | Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO4) 5 mmol/L for 20 min | Inhibition contractile response | [70] |

| Sugimoto, J. 2012 | In vivo and in vitro mononuclear cells | 2.5 mM MgSO4 1, 2, 4 h following LPS stimulation | Downregulation of inflammatory cytokines production, such as TNF-α and IL-6; reduction in NF-κB activation and nuclear localization | [71] |

| Study | Model and Design | Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| D’Agostino, G. 2009; Di Paola, R. 2016 | In vivo model | Inhibition of NF-kB levels | [82,83] |

| Motomura, K. 2022 | In vivo model | Inhibition of TNF-α, Il-1β, IL-6, inflammasome-dependent inflammatory pathways (NLRP3) | [84] |

| Esposito, G. 2014 | In vitro model | Inhibition of COX-2 and prostaglandins | [85] |

| Cerrato, S. 2010 | In vitro model | Inhibition of mast cells and the release of histamine, TNF-α, and prostaglandins | [96] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mappa, I.; Porcaro, G.; Derme, M.; Rizzo, G. Targeting Uterine Quiescence: A Multitarget Strategy with Vitamin D, High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid, Magnesium, and Palmitoylethanolamide to Prevent Preterm Birth. Nutrients 2026, 18, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010113

Mappa I, Porcaro G, Derme M, Rizzo G. Targeting Uterine Quiescence: A Multitarget Strategy with Vitamin D, High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid, Magnesium, and Palmitoylethanolamide to Prevent Preterm Birth. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010113

Chicago/Turabian StyleMappa, Ilenia, Giuseppina Porcaro, Martina Derme, and Giuseppe Rizzo. 2026. "Targeting Uterine Quiescence: A Multitarget Strategy with Vitamin D, High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid, Magnesium, and Palmitoylethanolamide to Prevent Preterm Birth" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010113

APA StyleMappa, I., Porcaro, G., Derme, M., & Rizzo, G. (2026). Targeting Uterine Quiescence: A Multitarget Strategy with Vitamin D, High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid, Magnesium, and Palmitoylethanolamide to Prevent Preterm Birth. Nutrients, 18(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010113