Purified Anthocyanins Indicated No Significant Effect on Arterial Stiffness, Four-Limb Blood Pressures and Cardiovascular Risk—A 12-Week Dose–Response Trial in Chinese Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults with Hyperglycemia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

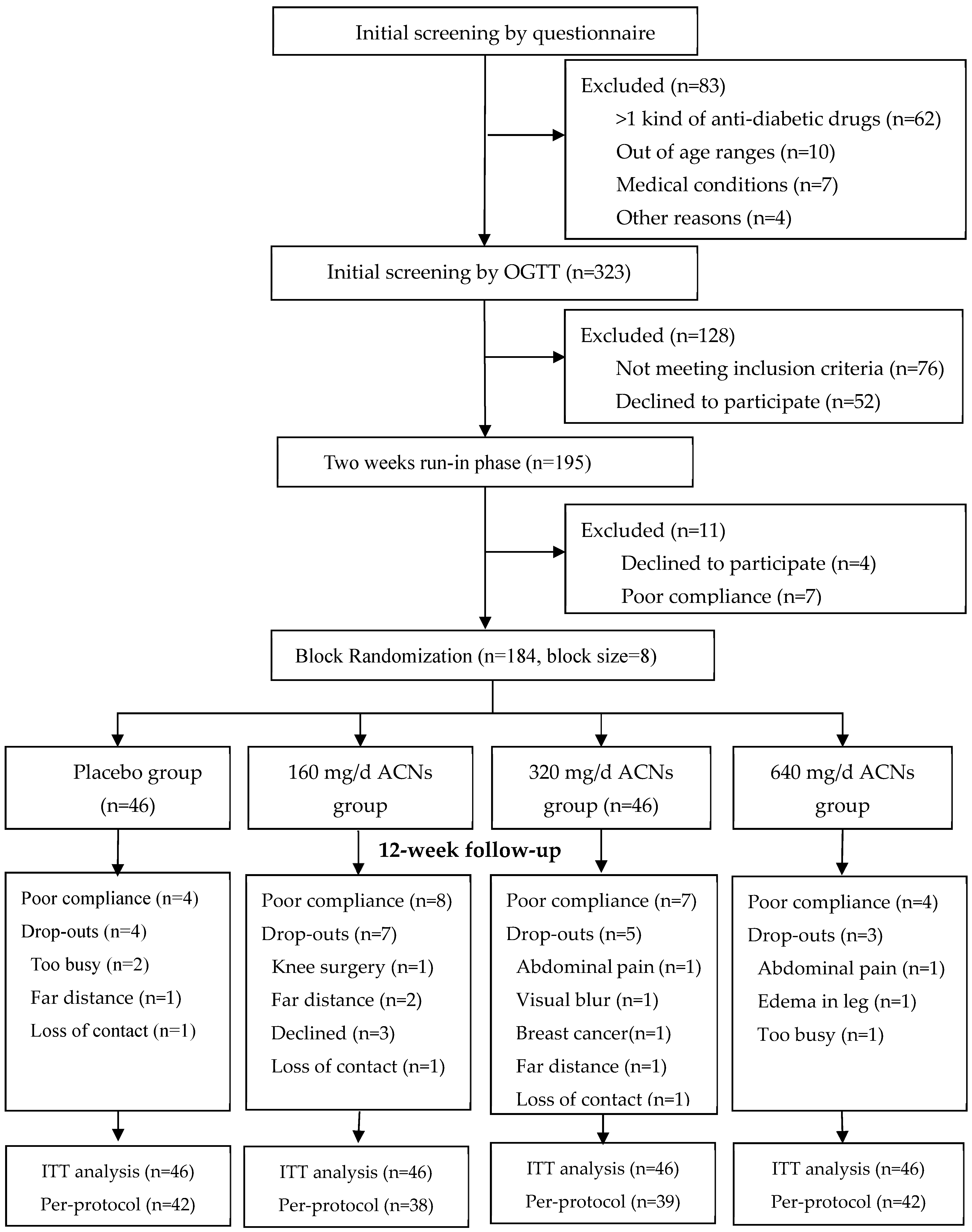

2.1. Participants Recruitment

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Supplements, Randomization and Allocation

2.4. Instructions to Participants and Compliance Assessment

2.5. Data Collection

2.5.1. Questionnaire Survey and Anthropometric Measures

2.5.2. Arterial Stiffness and Four-Limb Blood Pressures

2.5.3. Specimens Collection and Biochemical Testing

2.6. Sample Size and Power Estimation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Current Findings

4.2. Results Explanation

4.3. Study Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, Z. Cyanidin-3-glucoside: Targeting atherosclerosis through gut microbiota and anti-inflammation. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1627868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, E.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Ghanem, N.; Vazquez, A.R.; Johnson, S.A. Protective effects of blueberries on vascular function: A narrative review of preclinical and clinical evidence. Nutr. Res. 2023, 120, 20–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, E.; Hein, S.; Heiss, C.; Williams, C.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A. Blueberries and cardiovascular disease prevention. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 7621–7633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilamand, M.; Kelaiditi, E.; Guyonnet, S.; Antonelli Incalzi, R.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Vellas, B.; Cesari, M. Flavonoids and arterial stiffness: Promising perspectives. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, A.; Welch, A.A.; Fairweather-Tait, S.J.; Kay, C.; Minihane, A.M.; Chowienczyk, P.; Jiang, B.; Cecelja, M.; Spector, T.; Macgregor, A.; et al. Higher anthocyanin intake is associated with lower arterial stiffness and central blood pressure in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairlie-Jones, L.; Davison, K.; Fromentin, E.; Hill, A.M. The Effect of Anthocyanin-Rich Foods or Extracts on Vascular Function in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2017, 9, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Slavin, M.; Frankenfeld, C.L. Systematic Review of Anthocyanins and Markers of Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2016, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, S.; Shirani, M.; Shokri-Mashhadi, N.; Sadeghi, O.; Karav, S.; Bagherniya, M.; Sahebkar, A. The long-term and post-prandial effects of berry consumption on endothelial dysfunction in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 76, 134–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, N.; Heinz, V.; Ax, T.; Fesseler, L.; Patzak, A.; Bothe, T.L. Pulse Wave Velocity: Methodology, Clinical Applications, and Interplay with Heart Rate Variability. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, I.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, B.H.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, C.W.; Kim, M.C.; Ahn, J.H.; et al. Arterial stiffness is an independent predictor for risk of mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: The REBOUND study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, F.; He, J.; Cao, H.; Hu, X. Predictive value of abnormal ankle-brachial index in patients with diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 174, 108723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.H.; Lin, H.D.; Kwok, C.F.; Won, J.G.; Chen, H.S.; Chu, C.H.; Hwu, C.M.; Kuo, C.S.; Jap, T.S.; Shih, K.C.; et al. The combination of the ankle brachial index and brachial ankle pulse wave velocity exhibits a superior association with outcomes in diabetic patients. Intern. Med. 2014, 53, 2425–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Liu, Y.; Ma, S.; Bao, Q.; Sun, J.; Su, Y.; Cai, S.; Cheng, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Effects of ankle-brachial index and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity on all-cause mortality in a community-based elderly population. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 883651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomiyama, H.; Ohkuma, T.; Ninomiya, T.; Mastumoto, C.; Kario, K.; Hoshide, S.; Kita, Y.; Inoguchi, T.; Maeda, Y.; Kohara, K.; et al. Simultaneously Measured Interarm Blood Pressure Difference and Stroke: An Individual Participants Data Meta-Analysis. Hypertension 2018, 71, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, P.; Su, H. Four-Limb Blood Pressure Measurement with an Oscillometric Device: A Tool for Diagnosing Peripheral Vascular Disease. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2019, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Sun, L.; He, Y.; Xu, X.; Gan, L.; Guo, T.; Yang, L. Association between four-limb blood pressure differences and arterial stiffness: A cross-sectional study. Postgrad. Med. 2022, 134, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.E.; Warren, F.C.; Boddy, K.; McDonagh, S.T.J.; Moore, S.F.; Goddard, J.; Reed, N.; Turner, M.; Alzamora, M.T.; Ramos Blanes, R.; et al. Associations Between Systolic Interarm Differences in Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes and Mortality: Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis, Development and Validation of a Prognostic Algorithm: The INTERPRESS-IPD Collaboration. Hypertension 2021, 77, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Bannuru, R.R.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Ekhlaspour, L.; Gaglia, J.L.; Hilliard, M.E.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S20–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X.; Ho, S.C. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency Questionnaire among Chinese women in Guangdong province. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 18, 240–250. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.X. China Food Composition Tables, 6th ed.; Peking University Medical Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Whitt, M.C.; Irwin, M.L.; Swartz, A.M.; Strath, S.J.; O’Brien, W.L.; Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Schmitz, K.H.; Emplaincourt, P.O.; et al. Compendium of physical activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, S498–S504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Huo, Y.; Xu, X.; Qin, X.; Tang, G.; Xing, H.; Fan, F.; Cui, W.; et al. Age, arterial stiffness, and components of blood pressure in Chinese adults. Medicine 2014, 93, e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cho-lesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Ling, W.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Z.; Du, Z.; Chen, J.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L. Role of Purified Anthocyanins in Improving Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Chinese Men and Women with Prediabetes or Early Untreated Diabetes-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schielzeth, H.; Dingemanse, N.J.; Nakagawa, S.; Westneat, D.F.; Allegue, H.; Teplitsky, C.; Réale, D.; Dochtermann, N.A.; Garamszegi, L.Z.; Araya-Ajoy, Y.G. Robustness of Linear Mixed-Effects Models to Violations of Distributional Assumptions. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2020, 11, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozos, I.; Flangea, C.; Vlad, D.C.; Gug, C.; Mozos, C.; Stoian, D.; Luca, C.T.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; Horbańczuk, O.K.; Atanasov, A.G. Effects of Anthocyanins on Vascular Health. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimble, R.; Keane, K.M.; Lodge, J.K.; Howatson, G. The Influence of Tart Cherry (Prunus cerasus, cv Montmorency) Concentrate Supplementation for 3 Months on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Middle-Aged Adults: A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, A.; Mathew, S.; Moore, C.T.; Russell, J.; Robinson, E.; Soumpasi, V.; Barker, M.E. Effect of a tart cherry juice supplement on arterial stiffness and inflammation in healthy adults: A randomised controlled trial. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2014, 69, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, W.J.; Armah, C.N.; Doleman, J.F.; Perez-Moral, N.; Winterbone, M.S.; Kroon, P.A. 4-Week consumption of anthocyanin-rich blood orange juice does not affect LDL-cholesterol or other biomarkers of CVD risk and glycaemia compared with standard orange juice: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.; Navaei, N.; Pourafshar, S.; Jaime, S.J.; Akhavan, N.S.; Alvarez-Alvarado, S.; Proaño, G.V.; Litwin, N.S.; Clark, E.A.; Foley, E.M.; et al. Effects of Montmorency Tart Cherry Juice Consumption on Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in Adults with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, P.J.; van der Velpen, V.; Berends, L.; Jennings, A.; Feelisch, M.; Umpleby, A.M.; Evans, M.; Fernandez, B.O.; Meiss, M.S.; Minnion, M.; et al. Blueberries improve biomarkers of cardiometabolic function in participants with metabolic syndrome-results from a 6-month, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, E.K.; Terwoord, J.D.; Litwin, N.S.; Vazquez, A.R.; Lee, S.Y.; Ghanem, N.; Michell, K.A.; Smith, B.T.; Grabos, L.E.; Ketelhut, N.B.; et al. Daily blueberry consumption for 12 weeks improves endothelial function in postmenopausal women with above-normal blood pressure through reductions in oxidative stress: A randomized controlled trial. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 2621–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, E.; Hein, S.; Mesnage, R.; Fernandes, F.; Abhayaratne, N.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bell, L.; Williams, C.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A. Wild blueberry (poly)phenols can improve vascular function and cognitive performance in healthy older individuals: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istas, G.; Wood, E.; Le Sayec, M.; Rawlings, C.; Yoon, J.; Dandavate, V.; Cera, D.; Rampelli, S.; Costabile, A.; Fromentin, E.; et al. Effects of aronia berry (poly)phenols on vascular function and gut microbiota: A double-blind randomized controlled trial in adult men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feresin, R.G.; Johnson, S.A.; Pourafshar, S.; Campbell, J.C.; Jaime, S.J.; Navaei, N.; Elam, M.L.; Akhavan, N.S.; Alvarez-Alvarado, S.; Tenenbaum, G.; et al. Impact of daily strawberry consumption on blood pressure and arterial stiffness in pre- and stage 1-hypertensive postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 4139–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisi, T.O.P.; Gorski, F.; Eibel, B.; Barbosa, E.; Boll, L.; Waclawovsky, G.; Lehnen, A.M. Dietary intake of anthocyanins improves arterial stiffness, but not endothelial function, in volunteers with excess weight: A randomized clinical trial. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohadwala, M.M.; Holbrook, M.; Hamburg, N.M.; Shenouda, S.M.; Chung, W.B.; Titas, M.; Kluge, M.A.; Wang, N.; Palmisano, J.; Milbury, P.E.; et al. Effects of cranberry juice consumption on vascular function in patients with coronary artery disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Sayec, M.; Xu, Y.; Laiola, M.; Gallego, F.A.; Katsikioti, D.; Durbidge, C.; Kivisild, U.; Armes, S.; Lecomte, M.; Fança-Berthon, P.; et al. The effects of Aronia berry (poly)phenol supplementation on arterial function and the gut microbiome in middle aged men and women: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 2549–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.; Figueroa, A.; Navaei, N.; Wong, A.; Kalfon, R.; Ormsbee, L.T.; Feresin, R.G.; Elam, M.L.; Hooshmand, S.; Payton, M.E.; et al. Daily blueberry consumption improves blood pressure and arterial stiffness in postmenopausal women with pre- and stage 1-hypertension: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumkum, R.; Aston-Mourney, K.; McNeill, B.A.; Hernández, D.; Rivera, L.R. Bioavailability of Anthocyanins: Whole Foods versus Extracts. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Akshit, F.N.U.; Mohan, M.S. Effects of anthocyanin supplementation in diet on glycemic and related cardiovascular biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1199815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañer, O.; Pintó, X.; Subirana, I.; Amor, A.J.; Ros, E.; Hernáez, Á.; Martínez-González, M.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Estruch, R.; et al. Remnant Cholesterol, Not LDL Cholesterol, Is Associated with Incident Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2712–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, S.D.; Wang, M.; Vine, D.F.; Raggi, P. Predictive utility of remnant cholesterol in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2024, 39, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, M.; Li, J.; Ge, J.; Li, Z.; Peng, H.; Zhang, M. Remnant cholesterol and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Coron. Artery Dis. 2024, 35, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raggi, P.; Becciu, M.L.; Navarese, E.P. Remnant cholesterol as a new lipid-lowering target to reduce cardiovascular events. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2024, 35, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Li, Y.; Xiao, W.; Song, Z.; Huang, N.; Wang, W.; Dong, X.; Jia, J.; Clarke, R.; et al. Elevated blood remnant cholesterol and triglycerides are causally related to the risks of cardiometabolic multimorbidity. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zha, L.; Ling, W.; Guo, H. A dose-response evaluation of purified anthocyanins on inflammatory and oxidative biomarkers and metabolic risk factors in healthy young adults: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrition 2020, 74, 110745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xie, J.; Zhang, H.; Pang, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Sun, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Anthocyanin supplementation at different doses improves cholesterol efflux capacity in subjects with dyslipidemia-a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Pang, J.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Ling, W. Anthocyanin supplementation improves anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory capacity in a dose-response manner in subjects with dyslipidemia. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Milenkovic, D.; Van de Wiele, T.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; de Roos, B.; Garcia-Conesa, M.T.; Landberg, R.; Gibney, E.R.; Heinonen, M.; Tomás-Barberán, F.; et al. Addressing the inter-individual variation in response to consumption of plant food bioactives: Towards a better understanding of their role in healthy aging and cardiometabolic risk reduction. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yeoh, E.K.; Yung, T.K.C.; Wong, M.C.S.; Dong, D.; Chen, X.; Chan, M.K.Y.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.; et al. Change in eating habits and physical activities before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional study via random telephone survey. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lei, S.M.; Le, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yao, W.; Gao, Z.; Cheng, S. Bidirectional Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdowns on Health Behaviors and Quality of Life among Chinese Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Jeon, K.H.; Choi, K.U.; Choi, H.I.; Sung, K.C. Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity as a Predictor of Diabetes Development: Elevated Risk Within Normal Range Values in a Low-Risk Population. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e037705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, R.R.; Wilkinson, I.B.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Avolio, A.P.; Chirinos, J.A.; Cockcroft, J.R.; Heffernan, K.S.; Lakatta, E.G.; McEniery, C.M.; Mitchell, G.F.; et al. Recommendations for Improving and Standardizing Vascular Research on Arterial Stiffness: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2015, 66, 698–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, S.S.; Scuteri, A.; Shetty, V.; Wright, J.G.; Muller, D.C.; Fleg, J.L.; Spurgeon, H.P.; Ferrucci, L.; Lakatta, E.G. Pulse wave velocity is an independent predictor of the longitudinal increase in systolic blood pressure and of incident hypertension in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachopoulos, C.; Aznaouridis, K.; Terentes-Printzios, D.; Ioakeimidis, N.; Stefanadis, C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with brachial-ankle elasticity index: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension 2012, 60, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.-W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; A Berlin, J.; et al. CONSORT 2025 Statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 2025, 388, e081123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anthocyanins Supplementation by Different Dosages (n = 46/Group) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 160 mg/d | 320 mg/d | 640 mg/d | p | |

| Age, years | 62.9 ± 8.0 | 63.8 ± 8.7 | 62.8 ± 8.9 | 60.2 ± 9.4 | 0.218 |

| Female, % | 37 (29.8%) | 27 (21.6%) | 28 (22.4%) | 33 (26.4%) | 0.091 |

| Diabetes, % | 26 (27.4%) | 23 (24.2%) | 23 (24.2%) | 23 (24.2%) | 0.899 |

| Prediabetes (sIFG/sIGT/both), % | 7/5/8 | 5/9/9 | 4/7/12 | 5/8/10 | 0.832 |

| Education, college and above, % | 9 (19.6%) | 13 (28.3%) | 12 (26.1%) | 15 (32.6%) | 0.607 |

| Marriage, singled, % | 11 (23.9%) | 5 (10.9%) | 10 (21.7%) | 5 (10.9%) | 0.110 |

| Baseline hyperlipidemia, % | 26 (28.6%) | 16 (17.6%) | 26 (28.6%) | 23 (25.3%) | 0.121 |

| Baseline hypertension, % | 19 (26.4%) | 18 (25.0%) | 20 (27.8%) | 15 (20.8%) | 0.734 |

| Baseline overweight, % | 30 (30.9%) | 24 (24.8%) | 23 (23.7%) | 20 (20.6%) | 0.203 |

| Medications at baseline, % | |||||

| Diabetes | 3 (6.5%) | 8 (17.4%) | 4 (8.7%) | 4 (8.7%) | 0.326 |

| Hypertension | 13 (28.3%) | 13 (28.3%) | 16 (34.8%) | 8 (17.4%) | 0.074 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | 1.000 |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 5 (10.9%) | 0 | 3 (6.5%) | 5 (10.9%) | 0.146 |

| Smoking, % | 3 (6.5%) | 3 (6.5%) | 2 (4.3%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0.935 |

| Alcohol drinking, % | 20 (43.5%) | 11 (23.9%) | 14 (30.4%) | 21 (45.7%) | 0.089 |

| Tea drinking, % | 39 (84.8%) | 39 (84.8%) | 38 (82.6%) | 40 (87.0%) | 0.953 |

| Coffee drinking, % | 16 (34.8%) | 7 (15.2%) | 15 (32.6%) | 11 (23.9%) | 0.130 |

| Anthropometrics | |||||

| Weight, kg | 64.0 ± 9.5 | 61.5 ± 10.0 | 64.8 ± 11.6 | 60.5 ± 12.8 | 0.205 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.1 ± 2.9 | 23.9 ± 2.9 | 24.5 ± 3.3 | 23.6 ± 3.6 | 0.120 |

| WHR | 0.890 ± 0.058 | 0.897 ± 0.058 | 0.900 ± 0.057 | 0.880 ± 0.062 | 0.417 |

| SBP, mmHg | 129.5 ± 16.5 | 128.2 ± 17.4 | 131.3 ± 17.8 | 130.0 ± 18.8 | 0.865 |

| DBP, mmHg | 80.7 ± 11.5 | 77.9 ± 10.8 | 81.1 ± 10.4 | 82.2 ± 10.2 | 0.277 |

| Max baPWV > 1800 cm/s, % | 13 (30.2%) | 11 (25.6%) | 12 (27.9%) | 7 (16.3%) | 0.501 |

| Min ABI < 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| sIAD > 15 mmHg, % | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0.613 |

| sIAND > 15 mmHg, % | 0 | 4 (44.4%) | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0.233 |

| Anthocyanins Supplementation by Different Dosages (n = 46/Group) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mg/d (Placebo) | 160 mg/d | 320 mg/d | 640 mg/d | p | |

| Nutrients | |||||

| Total energy, kcal/d | |||||

| baseline | 1884 ± 709 | 1913 ± 681 | 2042 ± 741 | 1963 ± 927 | 0.179 |

| week 12 | 1774 ± 787 | 1927 ± 702 | 1907 ± 699 | 1839 ± 731 | 0.257 |

| change | −109 ± 564 | 10 ± 782 | −136 ± 654 | −131 ± 748 | 0.920 |

| Protein, % total energy | |||||

| baseline | 21.2 ± 4.1 | 21.6 ± 5.4 | 21.1 ± 4.4 | 22.4 ± 4.5 | 0.531 |

| week 12 | 20.4 ± 4.3 | 21.7 ± 3.7 | 20.8 ± 4.4 | 22.7 ± 4.1 | 0.036 |

| change | −0.8 ± 4.2 | 0.1 ± 5.5 | −0.3 ± 3.9 | 0.4 ± 5.3 | 0.666 |

| Total fat, % total energy | |||||

| baseline * | 23.2 (20.1, 29.4) | 22.6 (17.3, 28.2) | 22.0 (18.2, 26.7) | 22.5 (18.4, 24.4) | 0.707 |

| week 12 | 23.5 ± 8.8 | 22.9 ± 7.5 | 24.7 ± 6.6 | 23.9 ± 8.1 | 0.752 |

| change | −0.7 ± 6.7 | −0.8 ± 6.5 | 1.1 ± 9.7 | 1.5 ± 8.0 | 0.362 |

| Carbohydrate, % total energy | |||||

| baseline | 58.7 ± 10.4 | 58.3 ± 12.0 | 58.3 ± 11.9 | 59.2 ± 9.6 | 0.975 |

| week 12 | 60.0 ± 12.0 | 58.4 ± 9.7 | 56.5 ± 9.6 | 56.8 ± 11.0 | 0.358 |

| change | 1.3 ± 9.2 | 0.1 ± 10.6 | −1.8 ± 14.3 | −2.5 ± 11.1 | 0.376 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/d | |||||

| baseline | 558.0 ± 342.0 | 535.9 ± 183.1 | 579.8 ± 365.8 | 564.0 ± 301.2 | 0.921 |

| week 12 | 502.6 ± 349.7 | 546.9 ± 199.3 | 623.1 ± 352.6 | 543.4 ± 285.8 | 0.289 |

| change * | −22.1 (−118.3, 24.3) | 0 (−71.5, 99.0) | 0 (−87.7, 132.4) | 10.4 (−132.3, 99.2) | 0.174 |

| Food groups, g/d | |||||

| Total grains, g/d | |||||

| baseline * | 481.8 (384.1, 574.8) | 480.8 (359.6, 664.2) | 499.5 (316.8, 649.2) | 478.4 (333.5, 662.7) | 0.459 |

| week 12 * | 490.0 (382.4, 573.3) | 498.8 (302.3, 703.4) | 465.2 (328.9, 610.2) | 467.0 (286.3, 558.5) | 0.953 |

| change | 1.4 ± 156.8 | 6.6 ± 229.9 | −20.8 ± 241.7 | −56.5 ± 202.0 | 0.465 |

| Vegetables, g/d | |||||

| baseline | 600.0 ± 608.8 | 597.2 ± 266.4 | 615.0 ± 393.8 | 595.4 ± 457.9 | 0.892 |

| week 12 | 609.3 ± 624.6 | 620.0 ± 246.9 | 526.6 ± 251.3 | 582.6 ± 390.3 | 0.695 |

| change | −50.7 ± 275.1 | 22.9 ± 274.2 | −88.4 ± 319.8 | −12.8 ± 426.4 | 0.406 |

| Fruits, g/d | |||||

| baseline | 245.6 ± 273.5 | 214.8 ± 255.2 | 222.2 ± 177.3 | 247.2 ± 350.1 | 0.918 |

| week 12 | 192.6 ± 149.8 | 261.8 ± 239.5 | 220.1 ± 135.4 | 245.7 ± 324.4 | 0.479 |

| change | −52.9 ± 260.8 | 46.9 ± 254.5 | −2.1 ± 202.8 | −1.4 ± 211.5 | 0.244 |

| Red and processed meat, g/d | |||||

| baseline | 108.9 ± 78.9 | 96.8 ± 92.4 | 113.5 ± 100.0 | 105.5 ± 99.0 | 0.850 |

| week 12 | 93.9 ± 68.4 | 102.4 ± 102.1 | 108.8 ± 94.7 | 99.4 ± 69.1 | 0.864 |

| change | −15.0 ± 72.29 | 5.6 ± 102.2 | −4.7 ± 122.0 | −6.1 ± 78.5 | 0.784 |

| Sedentary time, hrs/d | |||||

| baseline | 2.348 ± 2.063 | 2.500 ± 1.880 | 2.326 ± 1.898 | 2.576 ± 2.119 | 0.918 |

| week 12 | 2.435 ± 2.177 | 2.526 ± 2.400 | 2.630 ± 2.339 | 2.614 ± 2.703 | 0.979 |

| change | 0.087 ± 2.140 | 0.026 ± 2.111 | 0.304 ± 1.618 | 0.038 ± 2.313 | 0.909 |

| Total PA, Met/h/week | |||||

| baseline | 87.7 ± 66.7 | 67.6 ± 62.7 | 65.6 ± 58.0 | 67.6 ± 52.4 | 0.251 |

| week 12 * | 62.1 (34.6, 140.9) | 44.5 (26.1, 112.0) | 49.0 (28.6, 75.3) | 49.0 (25.9, 84.5) | 0.385 |

| change | −0.741 ± 64.457 | 6.905 ± 41.632 | −6.325 ± 55.652 | −4.049 ± 54.275 | 0.678 |

| Supplementation of Purified Anthocyanins | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 46) | 160 mg/d (n = 46) | 320 mg/d (n = 46) | 640 mg/d (n = 46) | Poverall | Ptrend | |

| Right PWV, cm/s | ||||||

| baseline | 1587.3 ± 312.8 | 1559.8 ± 335.9 | 1560.3 ± 333.2 | 1486.6 ± 298.9 | 0.490 | |

| week 12 | 1552.6 ± 300.1 | 1563.8 ± 317.3 | 1519.8 ± 263.2 | 1468.7 ± 283.4 | 0.401 | |

| change | −34.6 ± 193.1 | 5.26 ± 233.6 | −40.4 ± 230.1 | −23.5 ± 156.6 | 0.719 | 0.514 |

| change% | −1.64 ± 10.85 | 1.40 ± 14.49 | −0.42 ± 18.71 | −1.00 ± 10.21 | 0.751 | 0.547 |

| Left PWV, cm/s | ||||||

| baseline | 1586.0 ± 314.3 | 1590.5 ± 352.7 | 1532.3 ± 326.7 | 1481.0 ± 287.7 | 0.325 | |

| week 12 | 1523.1 ± 287.2 | 1565.5 ± 339.0 | 1506.0 ± 287.6 | 1451.1 ± 273.1 | 0.325 | |

| change | −62.9 ± 210.9 | −24.3 ± 251.1 | −26.3 ± 205.0 | −30.4 ± 168.6 | 0.796 | 0.760 |

| change% | −3.14 ± 12.22 | −0.43 ± 14.75 | −0.22 ± 14.95 | −1.45 ± 10.91 | 0.711 | 0.602 |

| Max-PWV, cm/s | ||||||

| baseline | 1620.5 ± 317.4 | 1601.1 ± 353.9 | 1580.0 ± 333.3 | 1510.6 ± 296.5 | 0.405 | |

| week 12 | 1575.8 ± 300.6 | 1605.4 ± 332.3 | 1550.8 ± 266.4 | 1492.5 ± 280.5 | 0.309 | |

| change | −44.7 ± 192.5 | 5.4 ± 247.6 | −29.3 ± 212.8 | −18.4 ± 161.3 | 0.699 | 0.747 |

| change% | −2.21 ± 10.53 | 1.53 ± 14.47 | 0.02 ± 16.64 | −0.63 ± 10.17 | 0.601 | 0.715 |

| Right ABI | ||||||

| baseline | 1.143 ± 0.067 | 1.155 ± 0.079 | 1.153 ± 0.087 | 1.144 ± 0.082 | 0.866 | 0.981 |

| week 12 | 1.147 ± 0.088 | 1.153 ± 0.093 | 1.154 ± 0.082 | 1.135 ± 0.092 | 0.713 | 0.604 |

| change | 0.003 ± 0.081 | 0.004 ± 0.083 | 0.001 ± 0.072 | −0.011 ± 0.082 | 0.798 | 0.870 |

| change% | 0.419 ± 7.185 | 0.506 ± 6.894 | 0.282 ± 6.121 | −0.787 ± 7.094 | 0.785 | 0.843 |

| Left ABI | ||||||

| baseline | 1.137 ± 0.071 | 1.158 ± 0.088 | 1.137 ± 0.086 | 1.130 ± 0.084 | 0.420 | 0.466 |

| week 12 | 1.132 ± 0.071 | 1.145 ± 0.092 | 1.136 ± 0.094 | 1.126 ± 0.084 | 0.757 | 0.618 |

| change | −0.004 ± 0.062 | −0.007 ± 0.092 | −0.000 ± 0.065 | −0.003 ± 0.100 | 0.985 | 0.942 |

| change% | −0.237 ± 5.496 | −0.274 ± 7.704 | 0.085 ± 5.811 | 0.095 ± 9.140 | 0.991 | 0.988 |

| Min-ABI | ||||||

| baseline | 1.119 ± 0.069 | 1.126 ± 0.077 | 1.120 ± 0.076 | 1.114 ± 0.077 | 0.893 | |

| week 12 | 1.117 ± 0.085 | 1.123 ± 0.088 | 1.122 ± 0.084 | 1.109 ± 0.085 | 0.858 | |

| change | −0.001 ± 0.082 | −0.003 ± 0.069 | 0.002 ± 0.059 | −0.005 ± 0.088 | 0.976 | 0.883 |

| change% | 0.051 ± 7.311 | −0.172 ± 5.952 | 0.228 ± 5.256 | −0.226 ± 8.196 | 0.988 | 0.924 |

| Supplementation of Purified Anthocyanins | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 46) | 160 mg/d (n = 46) | 320 mg/d (n = 46) | 640 mg/d (n = 46) | Poverall | Ptrend | |

| Left-brachial SBP, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 129.2 ± 13.2 | 125.7 ± 13.3 | 127.4 ± 13.3 | 127.1 ± 19.2 | 0.693 | |

| week 12 | 125.1 ± 11.1 | 122.7 ± 12.8 | 123.8 ± 11.4 | 122.0 ± 18.1 | 0.742 | |

| change | −4.2 ± 10.5 | −2.9 ± 11.2 | −3.6 ± 10.4 | −5.0 ± 10.6 | 0.749 | 0.609 |

| change% | −2.8 ± 8.1 | −2.0 ± 8.5 | −2.4 ± 7.7 | −3.6 ± 8.3 | 0.752 | 0.572 |

| Left-brachial DBP, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 73.8 ± 8.7 | 71.7 ± 9.5 | 73.7 ± 9.4 | 74.1 ± 11.7 | 0.562 | |

| week 12 | 71.8 ± 8.0 | 70.9 ± 9.6 | 71.9 ± 9.3 | 72.4 ± 11.2 | 0.885 | |

| change | −2.00 ± 7.15 | −0.89 ± 7.72 | −1.78 ± 8.46 | −1.70 ± 7.52 | 0.841 | 0.965 |

| change% | −2.18 ± 9.65 | −0.71 ± 10.45 | −1.75 ± 11.88 | −1.76 ± 10.12 | 0.865 | 0.992 |

| Left-brachial MAP, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 97.0 ± 12.2 | 95.0 ± 11.5 | 95.7 ± 11.2 | 95.5 ± 15.5 | 0.849 | |

| week 12 | 94.4 ± 10.0 | 92.0 ± 11.4 | 93.5 ± 10.1 | 93.3 ± 15.0 | 0.828 | |

| change | −2.63 ± 10.23 | −3.02 ± 9.33 | −2.15 ± 10.17 | −2.24 ± 8.27 | 0.993 | 0.795 |

| change% | −1.94 ± 10.88 | −2.77 ± 9.52 | −1.62 ± 10.19 | −1.96 ± 8.62 | 0.986 | 0.912 |

| Right-brachial SBP, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 129.3 ± 13.8 | 125.4 ± 13.4 | 125.6 ± 13.9 | 126.1 ± 19.8 | 0.561 | |

| week 12 | 125.3 ± 12.7 | 123.9 ± 13.3 | 124.2 ± 11.8 | 121.5 ± 17.3 | 0.626 | |

| change | −4.0 ± 11.5 | −1.5 ± 10.9 | −1.3 ± 11.9 | −4.6 ± 9.2 | 0.297 | 0.785 |

| change% | −2.7 ± 8.8 | −0.8 ± 8.7 | −0.5 ± 9.4 | −3.0 ± 8.3 | 0.353 | 0.862 |

| Right-brachial DBP, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 74.4 ± 9.5 | 71.9 ± 9.5 | 72.4 ± 9.2 | 73.0 ± 14.5 | 0.661 | |

| week 12 | 71.8 ± 9.2 | 70.7 ± 9.3 | 72.1 ± 9.1 | 71.0 ± 11.7 | 0.902 | |

| change | −2.6 ± 8.6 | −1.2 ± 6.5 | −0.3 ± 7.4 | −2.1 ± 8.1 | 0.449 | 0.670 |

| change% | −2.8 ± 11.9 | −1.2 ± 9.3 | 0.1 ± 10.6 | −0.1 ± 24.7 | 0.789 | 0.368 |

| Right-brachial MAP, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 97.8 ± 12.3 | 94.9 ± 11.1 | 94.5 ± 11.9 | 94.8 ± 17.5 | 0.579 | |

| week 12 | 94.6 ± 10.6 | 93.3 ± 10.8 | 94.8 ± 10.4 | 92.6 ± 14.4 | 0.785 | |

| change | −3.2 ± 10.7 | −1.6 ± 8.2 | 0.3 ± 11.4 | −2.1 ± 9.4 | 0.386 | 0.485 |

| change% | −2.5 ± 11.4 | −1.3 ± 8.9 | 1.1 ± 12.1 | −0.6 ± 16.2 | 0.573 | 0.355 |

| Left-ankle SBP, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 149.5 ± 20.3 | 146.8 ± 18.1 | 146.7 ± 21.0 | 145.9 ± 26.3 | 0.872 | |

| week 12 | 144.4 ± 16.8 | 143.8 ± 17.3 | 143.4 ± 17.9 | 139.6 ± 23.0 | 0.621 | |

| Change | −5.1 ± 15.2 | −3.0 ± 14.1 | −3.3 ± 12.4 | −6.3 ± 16.1 | 0.665 | 0.685 |

| change% | −2.7 ± 9.7 | −1.6 ± 9.6 | −1.7 ± 7.9 | −3.5 ± 10.7 | 0.739 | 0.693 |

| Right-ankle SBP, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 150.4 ± 19.1 | 146.5 ± 18.3 | 148.8 ± 20.8 | 147.9 ± 25.4 | 0.851 | |

| week 12 | 146.0 ± 17.7 | 144.5 ± 16.7 | 145.8 ± 18.4 | 140.7 ± 23.4 | 0.525 | |

| Change | −4.3 ± 14.8 | −2.0 ± 12.9 | −3.0 ± 14.2 | −7.1 ± 13.4 | 0.325 | 0.307 |

| change% | −2.4 ± 9.4 | −0.9 ± 8.5 | −1.4 ± 9.6 | −4.4 ± 8.6 | 0.276 | 0.276 |

| sIAD, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 4.130 ± 3.110 | 4.370 ± 4.255 | 4.935 ± 4.459 | 4.348 ± 5.551 | 0.842 | |

| week 12 | 4.326 ± 3.590 | 4.544 ± 4.722 | 4.544 ± 5.184 | 4.239 ± 4.100 | 0.983 | |

| Change | 0.196 ± 4.612 | 0.174 ± 2.719 | −0.391 ± 4.674 | −0.109 ± 7.024 | 0.935 | 0.654 |

| change% * | 0 (−60.0, 100.0) | 0 (−50.0, 76.7) | 0 (−60.0, 50.0) | 0 (−58.3, 200.0) | 0.479 | 0.710 |

| sIAND, mmHg | ||||||

| baseline | 5.500 ± 3.494 | 6.174 ± 6.819 | 6.283 ± 6.473 | 6.044 ± 4.477 | 0.907 | |

| week 12 | 5.783 ± 6.401 | 6.609 ± 6.923 | 5.739 ± 5.277 | 5.196 ± 5.171 | 0.728 | |

| change | 0.283 ± 7.638 | 0.435 ± 7.562 | −0.544 ± 6.706 | −0.848 ± 6.606 | 0.788 | 0.355 |

| change% | 80.4 ± 356.2 | 55.2 ± 272.7 | 74.7 ± 288.2 | 38.7 ± 188.9 | 0.896 | 0.872 |

| Supplementation of Purified Anthocyanins | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 46) | 160 mg/d (n = 46) | 320 mg/d (n = 46) | 640 mg/d (n = 46) | Poverall | Ptrend | |

| RC, mmol/L | ||||||

| baseline | 0.599 ± 0.522 | 0.476 ± 0.328 | 0.650 ± 0.527 | 0.615 ± 0.560 | 0.367 | |

| week 12 | 0.564 ± 0.438 | 0.541 ± 0.388 | 0.556 ± 0.465 | 0.652 ± 0.642 | 0.705 | |

| change | −0.035 ± 0.374 | 0.064 ± 0.273 | −0.094 ± 0.243 | 0.037 ± 0.271 | 0.048 | 0.773 |

| change% * | 2.7 (−31.0, 39.9) | 0 (−18.4, 47.8) | −6.8 (−32.2, 10.8) | 13.2 (−17.6, 75.1) | 0.034 | 0.746 |

| Non-HDL-c, mmol/L | ||||||

| baseline | 4.000 ± 1.001 | 3.764 ± 1.067 | 3.899 ± 1.081 | 3.926 ± 0.964 | 0.742 | |

| week 12 | 3.933 ± 0.965 | 3.992 ± 1.065 | 3.944 ± 1.084 | 3.905 ± 0.988 | 0.982 | |

| change | −0.065 ± 0.520 | 0.228 ± 0.570 | 0.044 ± 0.489 | −0.021 ± 0.468 | 0.037 | 0.877 |

| change% | −0.340 ± 13.471 | 7.371 ± 16.567 | 1.747 ± 13.070 | 0.128 ± 12.340 | 0.033 | 0.647 |

| TG/HDL-c | ||||||

| baseline | 1.609 ± 2.256 | 1.081 ± 0.851 | 1.616 ± 1.406 | 1.814 ± 3.120 | 0.379 | |

| week 12 | 1.341 ± 1.320 | 1.187 ± 1.485 | 1.333 ± 0.892 | 1.686 ± 3.312 | 0.666 | |

| change | −0.269 ± 1.316 | 0.106 ± 0.854 | −0.283 ± 1.005 | −0.128 ± 1.346 | 0.338 | 0.965 |

| change% | 7.381 ± 56.469 | 7.292 ± 44.389 | −4.429 ± 32.179 | −0.310 ± 30.692 | 0.451 | 0.213 |

| TyG-index | ||||||

| baseline | 8.989 ± 0.548 | 8.779 ± 0.475 | 9.044 ± 0.662 | 8.976 ± 0.626 | 0.144 | |

| week 12 | 8.988 ± 0.498 | 8.816 ± 0.552 | 8.966 ± 0.560 | 8.930 ± 0.595 | 0.452 | |

| change | −0.001 ± 0.378 | 0.038 ± 0.325 | −0.078 ± 0.346 | −0.046 ± 0.302 | 0.382 | 0.262 |

| change% | 0.100 ± 4.185 | 0.447 ± 3.700 | −0.728 ± 3.651 | −0.439 ± 3.366 | 0.433 | 0.259 |

| TyG-BMI | ||||||

| baseline | 225.7 ± 29.1 | 210.3 ± 31.0 | 221.3 ± 33.7 | 212.6 ± 39.4 | 0.097 | |

| week 12 | 225.7 ± 32.8 | 211.5 ± 32.0 | 219.1 ± 30.9 | 210.9 ± 39.8 | 0.126 | |

| change | −0.047 ± 12.368 | 1.200 ± 9.679 | −2.238 ± 11.054 | −1.712 ± 9.066 | 0.390 | 0.230 |

| change% | −0.098 ± 5.426 | 0.627 ± 4.655 | −0.704 ± 4.825 | −0.739 ± 4.222 | 0.484 | 0.306 |

| VAI | ||||||

| baseline * | 1.608 (1.151, 2.385) | 1.318 (0.878, 2.086) | 1.731 (1.209, 3.516) | 1.425 (1.065, 2.477) | 0.206 | |

| week 12 | 2.400 ± 2.418 | 1.876 ± 2.036 | 2.186 ± 1.442 | 2.998 ± 6.596 | 0.533 | |

| change | −0.454 ± 2.411 | 0.095 ± 1.198 | −0.530 ± 1.760 | −0.292 ± 2.504 | 0.473 | 0.919 |

| change% | 8.504 ± 57.948 | 6.017 ± 44.244 | −6.004 ± 31.911 | −2.144 ± 30.090 | 0.321 | 0.119 |

| FRS | ||||||

| baseline | 14.4 ± 3.3 | 13.5 ± 4.1 | 14.0 ± 3.7 | 13.2 ± 4.4 | 0.482 | |

| week 12 | 14.1 ± 3.4 | 13.9 ± 4.1 | 13.9 ± 3.9 | 13.0 ± 4.2 | 0.507 | |

| change | −0.3 ± 1.7 | 0.3 ± 1.8 | −0.04 ± 1.5 | −0.2 ± 2.0 | 0.359 | 0.953 |

| change% | −1.7 ± 13.4 | 5.9 ± 26.2 | −0.2 ± 11.1 | 4.0 ± 31.9 | 0.335 | 0.460 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Long, H.; Liu, R.; Chiou, J.; Chen, C. Purified Anthocyanins Indicated No Significant Effect on Arterial Stiffness, Four-Limb Blood Pressures and Cardiovascular Risk—A 12-Week Dose–Response Trial in Chinese Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults with Hyperglycemia. Nutrients 2026, 18, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010112

Liu Z, Li M, Chen Y, Wang C, Chen J, Long H, Liu R, Chiou J, Chen C. Purified Anthocyanins Indicated No Significant Effect on Arterial Stiffness, Four-Limb Blood Pressures and Cardiovascular Risk—A 12-Week Dose–Response Trial in Chinese Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults with Hyperglycemia. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010112

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhaomin, Minmin Li, Yuming Chen, Cheng Wang, Jianyin Chen, Huanhuan Long, Ruqing Liu, Jiachi Chiou, and Chaogang Chen. 2026. "Purified Anthocyanins Indicated No Significant Effect on Arterial Stiffness, Four-Limb Blood Pressures and Cardiovascular Risk—A 12-Week Dose–Response Trial in Chinese Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults with Hyperglycemia" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010112

APA StyleLiu, Z., Li, M., Chen, Y., Wang, C., Chen, J., Long, H., Liu, R., Chiou, J., & Chen, C. (2026). Purified Anthocyanins Indicated No Significant Effect on Arterial Stiffness, Four-Limb Blood Pressures and Cardiovascular Risk—A 12-Week Dose–Response Trial in Chinese Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults with Hyperglycemia. Nutrients, 18(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010112