Emotional and Uncontrolled Eating Mediate the Well-Being–Adiposity Relationship in Women but Not in Men

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, Participants, and Protocol

2.2. Study Variables

2.2.1. Adiposity Parameters

2.2.2. Biochemical Analyses

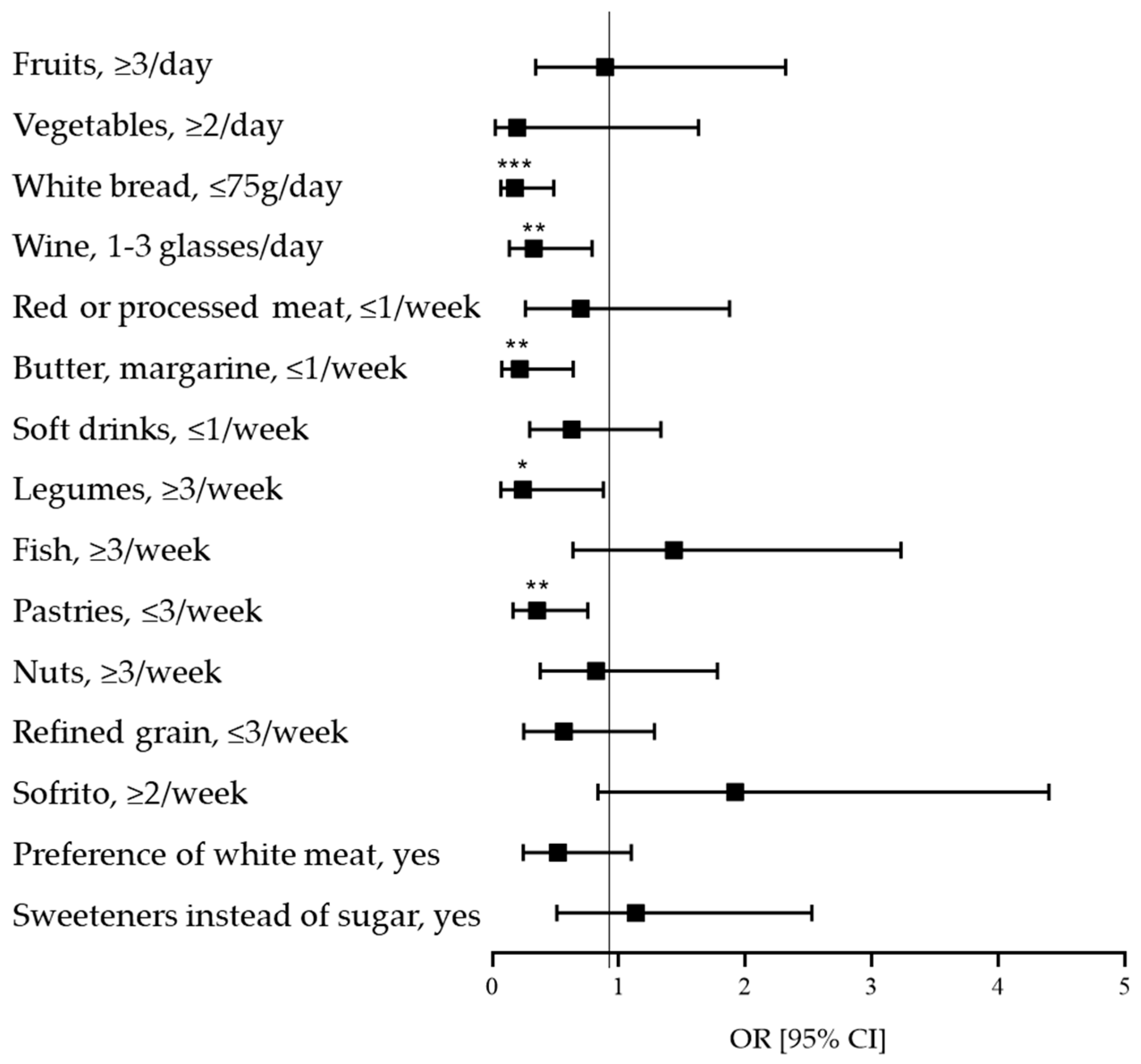

2.2.3. Diet Quality

2.2.4. Eating Behaviors

- Emotional eating, defined as the tendency to overeat when facing emotionally negative situations, assessed through six items.

- Cognitive restraint, defined as the conscious restriction of food intake to control or reduce weight, assessed through six items.

- Uncontrolled eating, defined as the tendency to overeat in response to a perceived loss of control over food intake, assessed through nine items.

2.2.5. Parameters Related to Mental Health

2.3. Covariates

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Asociations Between Adiposity Parameters, Diet Quality, Eating Behaviors and Stress in Men

3.2. Associations Between Adiposity Parameters, Diet Quality, Eating Behaviors, Well-Being and Stress in Women

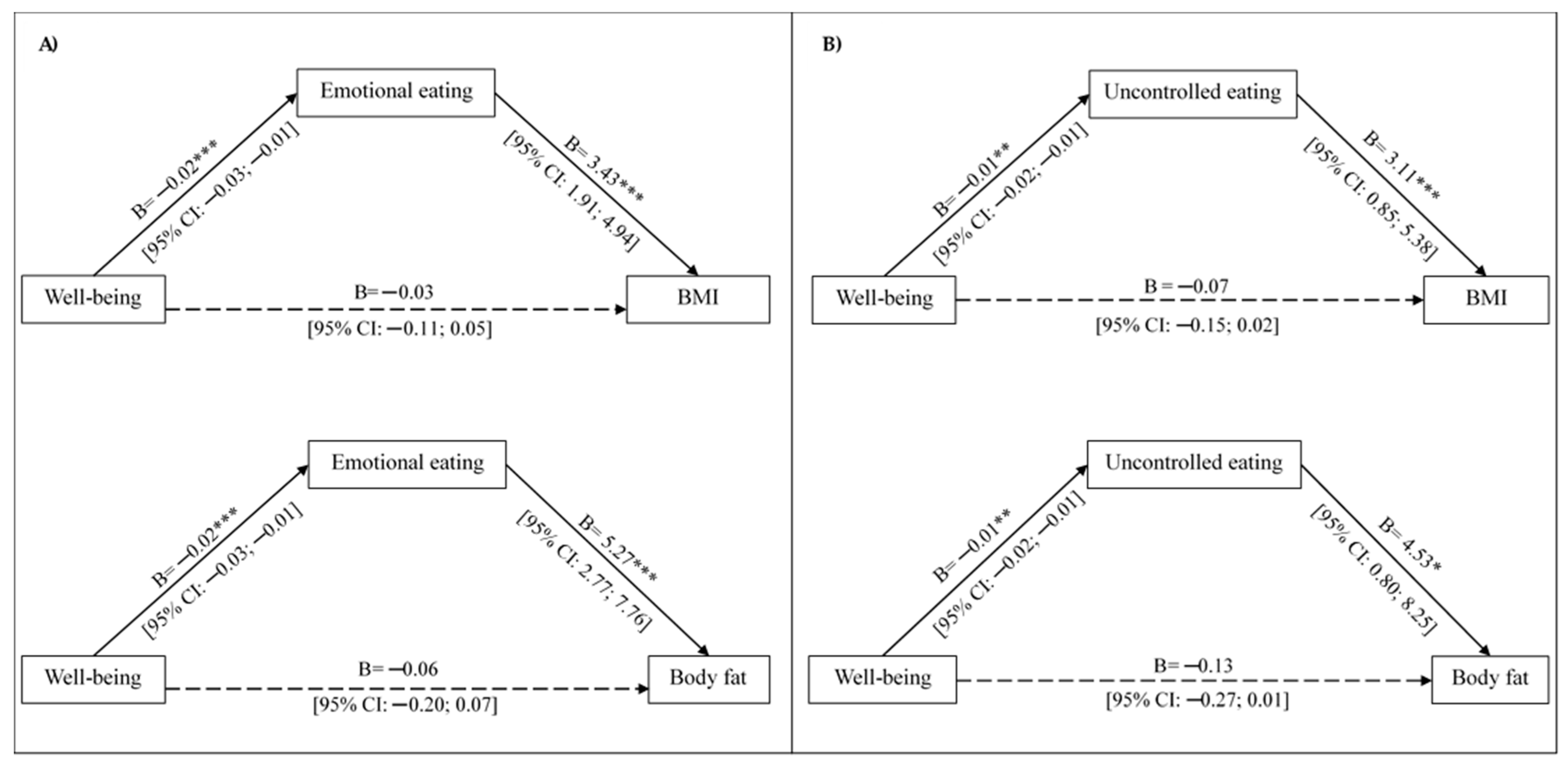

3.3. Emotional and Uncontrolled Eating Mediate the Association Between Well-Being and Adiposity Parameters in Women

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heidari, S.; Babor, T.F.; De Castro, P.; Tort, S.; Curno, M. Sex and Gender Equity in Research: Rationale for the SAGER Guidelines and Recommended Use. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2016, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraco, A.; Armani, A.; Gorini, S.; Camajani, E.; Quattrini, C.; Filardi, T.; Karav, S.; Strollo, R.; Caprio, M.; Lombardo, M. Gender Differences in Dietary Patterns and Eating Behaviours in Individuals with Obesity. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koceva, A.; Herman, R.; Janez, A.; Rakusa, M.; Jensterle, M. Sex- and Gender-Related Differences in Obesity: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anversa, R.G.; Muthmainah, M.; Sketriene, D.; Gogos, A.; Sumithran, P.; Brown, R.M. A Review of Sex Differences in the Mechanisms and Drivers of Overeating. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 63, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brytek-Matera, A. Negative Affect and Maladaptive Eating Behavior as a Regulation Strategy in Normal-Weight Individuals: A Narrative Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eik-Nes, T.T.; Tokatlian, A.; Raman, J.; Spirou, D.; Kvaløy, K. Depression, Anxiety, and Psychosocial Stressors across BMI Classes: A Norwegian Population Study—The HUNT Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 886148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Mentzelou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papandreou, D.; Spanoudaki, M.; Vasios, G.K.; Pavlidou, E.; Mantzorou, M.; Giaginis, C. The Association of Emotional Eating with Overweight/Obesity, Depression, Anxiety/Stress, and Dietary Patterns: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevich, I.; Camacho, M.E.I.; del Consuelo Velázquez-Alva, M.; Zepeda, M.Z. Relationship among Obesity, Depression, and Emotional Eating in Young Adults. Appetite 2016, 107, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Adjepong, M.; Zan, M.C.H.; Cho, M.J.; Fenton, J.I.; Hsiao, P.Y.; Keaver, L.; Lee, H.; Ludy, M.-J.; Shen, W.; et al. Gender Differences in the Relationships between Perceived Stress, Eating Behaviors, Sleep, Dietary Risk, and Body Mass Index. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janić, M.; Janež, A.; El-Tanani, M.; Rizzo, M. Obesity: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetto, L.; Dicker, D.; Frühbeck, G.; Halford, J.C.G.; Sbraccia, P.; Yumuk, V.; Goossens, G.H. A New Framework for the Diagnosis, Staging and Management of Obesity in Adults. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2395–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, L.P.; van de Weijer, M.P.; Bartels, M. The Human Physiology of Well-Being: A Systematic Review on the Association between Neurotransmitters, Hormones, Inflammatory Markers, the Microbiome and Well-Being. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 139, 104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist–Hip Ratio; Report of a WHO Expert Consultation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Unger, G.; Benozzi, S.F.; Perruzza, F.; Pennacchiotti, G.L. Triglycerides and Glucose Index: A Useful Indicator of Insulin Resistance. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2014, 61, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H.; Zomeño, M.D.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Vioque, J.; Romaguera, D.; Martínez, J.A.; Tinahones, F.J.; Miranda, J.L.; et al. Validity of the Energy-Restricted Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4971–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-García, M.; Vila-Maldonado, S.; Rodríguez-Gómez, I.; Faya, F.M.; Plaza-Carmona, M.; Pastor-Vicedo, J.C.; Ara, I. The Spanish Version of the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire-R21 for Children and Adolescents (TFEQ-R21C): Psychometric Analysis and Relationships with Body Composition and Fitness Variables. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 165, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelleri, J.C.; Bushmakin, A.G.; Gerber, R.A.; Leidy, N.K.; Sexton, C.C.; Lowe, M.R.; Karlsson, J. Psychometric Analysis of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R21: Results from a Large Diverse Sample of Obese and Non-Obese Participants. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Carrasco, R. Reliability and Validity of the Spanish Version of the World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index in Elderly. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 66, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara-Cabrera, M.L.; Mundal, I.P.; De Las Cuevas, C. Patient-Reported Well-Being: Psychometric Properties of the World Health Organization Well-Being Index in Specialised Community Mental Health Settings. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remor, E. Psychometric Properties of a European Spanish Version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Span. J. Psychol. 2006, 9, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román Viñas, B.; Ribas Barba, L.; Ngo, J.; Serra Majem, L. Validación En Población Catalana Del Cuestionario Internacional de Actividad Física. Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The PROCESS Macro for SPSS, SAS, and R—PROCESS Macro for SPSS, SAS, and R. Available online: https://www.processmacro.org/index.html (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Kajantie, E.; Phillips, D.I.W. The Effects of Sex and Hormonal Status on the Physiological Response to Acute Psychosocial Stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konttinen, H.; Van Strien, T.; Männistö, S.; Jousilahti, P.; Haukkala, A. Depression, Emotional Eating and Long-Term Weight Changes: A Population-Based Prospective Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlabicz, M.; Dubatówka, M.; Jamiołkowski, J.; Sowa, P.; Łapińska, M.; Raczkowski, A.; Łaguna, W.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A.M.; Waszkiewicz, N.; Kowalska, I.; et al. Subjective Well-Being in Non-Obese Individuals Depends Strongly on Body Composition. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualdi-russo, E.; Rinaldo, N.; Masotti, S.; Bramanti, B.; Zaccagni, L. Sex Differences in Body Image Perception and Ideals: Analysis of Possible Determinants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais, M.S.M.; Macêdo, S.G.G.F.; Nascimento, R.A.d.; Vieira, M.C.A.; Moreira, M.A.; da Câmara, S.M.A.; Almeida, M.d.G.; Maciel, Á.C.C. Dissatisfaction with Body Image and Weight Gain in Middle-Aged Women: A Cross Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0290380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Cooke, L. The Impact Obesity on Psychological Well-Being. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 19, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, N.A.; Kersting, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Luck-Sikorski, C. Body Dissatisfaction in Individuals with Obesity Compared to Normal-Weight Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Facts 2016, 9, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Heuer, C.A. The Stigma of Obesity: A Review and Update. Obesity 2009, 17, 941–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.M.; Brownell, K.D. Psychosocial Origins of Obesity Stigma: Toward Changing a Powerful and Pervasive Bias. Obes. Rev. 2003, 4, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh Gibson, E. Emotional Influences on Food Choice: Sensory, Physiological and Psychological Pathways. Physiol. Behav. 2006, 89, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Penaforte, F.R.; Minelli, M.C.S.; Anastácio, L.R.; Japur, C.C. Anxiety Symptoms and Emotional Eating Are Independently Associated with Sweet Craving in Young Adults. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerón-Rugerio, M.F.; Hernáez, Á.; Cambras, T.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Emotional Eating and Cognitive Restraint Mediate the Association between Sleep Quality and BMI in Young Adults. Appetite 2022, 170, 105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akillioglu, T.; Bas, M.; Kose, G. Restrained, Emotional Eating and Depression Can Be a Risk Factor for Metabolic Syndrome. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S.P.; Alessi, J.; Santos, Z.E.A.; De Mello, E.D. Association between Eating Behavior, Anthropometric and Biochemical Measurements, and Peptide YY (PYY) Hormone Levels in Obese Adolescents in Outpatient Care. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 33, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuente González, C.E.; Chávez-Servín, J.L.; De La Torre-Carbot, K.; Ronquillo González, D.; Aguilera Barreiro, M.D.L.Á.; Ojeda Navarro, L.R. Relationship between Emotional Eating, Consumption of Hyperpalatable Energy-Dense Foods, and Indicators of Nutritional Status: A Systematic Review. J. Obes. 2022, 2022, 4243868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Contreras, C.; Farrán-Codina, A.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M.; Zerón-Rugerio, M.F. A Higher Dietary Restraint Is Associated with Higher BMI: A Cross-Sectional Study in College Students. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 240, 113536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, V.; Polivy, J.; Herman, C.P. Perceived Healthiness of Food. If It’s Healthy, You Can Eat More! Appetite 2009, 52, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, S.E. Emotional Ratings of High- and Low-Calorie Food Are Differentially Associated with Cognitive Restraint and Dietary Restriction. Appetite 2018, 121, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Nasreen, A.; Menzel, A.; Gasmi Benahmed, A.; Pivina, L.; Noor, S.; Peana, M.; Chirumbolo, S.; Bjørklund, G. Neurotransmitters Regulation and Food Intake: The Role of Dietary Sources in Neurotransmission. Molecules 2022, 28, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegan, A.P.; Perry, I.J.; Phillips, C.M. The Association between Dietary Quality and Dietary Guideline Adherence with Mental Health Outcomes in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milte, C.M.; Thorpe, M.G.; Crawford, D.; Ball, K.; McNaughton, S.A. Associations of Diet Quality with Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Australian Men and Women. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 64, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soo, J.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Chen, Y.; Zevon, E.S.; Boehm, J.K. Psychological Well-Being and Restorative Biological Processes: HDL-C in Older English Adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 209, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, C.; Millar, S.R.; Kabir, Z. Associations between Adiposity Measures and Depression and Well-Being Scores: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Middle- to Older-Aged Adults. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrea, L.; Verde, L.; Suárez, R.; Frias-Toral, E.; Vásquez, C.A.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S.; Muscogiuri, G. Sex-Differences in Mediterranean Diet: A Key Piece to Explain Sex-Related Cardiovascular Risk in Obesity? A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadaki, A.; Nolen-Doerr, E.; Mantzoros, C.S. The Effect of the Mediterranean Diet on Metabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials in Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, P. The Role of Stress and Mental Health in Obesity. Obesities 2025, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupal Kumar, M.R.R. Shubhra Saraswat Obesity and Stress: A Contingent Paralysis. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, C.; Nassar, L.; Soumi, S.; El Osta, N.; Papazian, T.; Rabbaa Khabbaz, L. The Cognitive, Behavioral, and Emotional Aspects of Eating Habits and Association With Impulsivity, Chronotype, Anxiety, and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Women | Men | p-Value | |

| Sample size, % (n) | 63.4 (78) | 36.6 (45) | |

| Sociodemographic variables | |||

| Age, years | 35.4 ± 7.9 | 36.0 ± 7.8 | 0.695 |

| Educational level, % university degree | 93.6 | 84.4 | 0.101 |

| Employment status, % employed | 94.9 | 97.8 | 0.436 |

| Adiposity parameters | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.7 ± 5.9 | 29.1 ± 5.6 | 0.191 |

| Body fat, % | 36.3 ± 9.6 | 27.9 ± 8.7 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 81.1 ± 12.2 | 96.7 ± 12.2 | <0.001 |

| Hip circumference, cm | 108.5 ± 11.5 | 109.8 ± 10.0 | 0.511 |

| Waist-hip ratio, a.u. | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Eating behaviors | |||

| Emotional eating, score | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 0.017 |

| Uncontrolled eating, score | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 0.421 |

| Cognitive restraint, score | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 0.034 |

| Lifestyle variables | |||

| Physical activity, METs | 2222.6 ± 1671.9 | 2111.3 ± 1530.1 | 0.715 |

| Diet quality, score | 8.0 ± 2.1 | 6.5 ± 2.3 | <0.001 |

| Parameters related to mental health | |||

| Well-being, score | 61.6 ± 15.6 | 56.0 ± 16.5 | 0.064 |

| Stress, score | 14.6 ± 7.0 | 14.6 ± 4.8 | 0.999 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Glucose, mg/100 mL | 79.8 ± 7.4 | 86.5 ± 22.1 | 0.016 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 0.144 |

| Triglycerides, mg/100 mL | 68.5 ± 38.2 | 109.3 ± 52.3 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides-glucose index, a.u. | 7.8 ± 0.5 | 8.3 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/100 mL | 184.6 ± 30.4 | 191.2 ± 33.6 | 0.270 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/100 mL | 59.7 ± 12.0 | 47.5 ± 9.0 | <0.001 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/100 mL | 111.0 ± 26.6 | 120.4 ± 26.8 | 0.068 |

| Parameters Related to Mental Health | Eating Behaviors | Diet Quality, Score B [95%CI] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-Being, Score B [95%CI] | Stress, Score B [95%CI] | Emotional Eating, Score B [95%CI] | Uncontrolled Eating, Score B [95%CI] | Cognitive Restraint, Score B [95%CI] | ||

| Adiposity parameters | ||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.03 [−0.14; 0.08] | 0.43 [0.09; 0.77] * | 2.32 [−0.34; 4.98] | 3.92 [1.22; 6.61] ** | 2.92 [−0.44; 6.27] | −0.84 [−1.60; −0.08] * |

| Body fat, % | −0.06 [−0.23; 0.11] | 0.46 [−0.11; 1.03] | 1.77 [−2.58; 6.11] | 3.53 [−1.05; 8.12] | 5.31 [0.05; 10.58] * | −0.86 [−2.06; 0.35] |

| Waist circumference, cm | −0.02 [−0.25; 0.22] | 0.80 [0.05; 1.55] * | 6.33 [0.79; 11.87] * | 8.90 [3.21; 14.58] ** | 5.89 [−1.32; 13.09] | −1.82 [−3.44; −0.20] * |

| Hip circumference, cm | −0.04 [−0.24; 0.17] | 0.62 [−0.03; 1.27] | 4.71 [−0.16; 9.58] | 5.87 [0.71; 11.03] * | 6.40 [0.31; 12.50] * | −1.40 [−2.80; −0.01] * |

| Waist-hip, ratio, a.u. | 0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] | 0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] | 0.02 [−0.01; 0.05] | 0.04 [0.01; 0.06] * | 0.01 [−0.03; 0.04] | −0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] |

| Diet quality, score | 0.04 [0.01; 0.08] * | −0.05 [−0.20; 0.10] | −0.79 [−1.87; 0.29] | −0.48 [−1.69; 0.72] | 1.54 [0.30; 2.78] * | - |

| Biochemical parameters | ||||||

| Glucose, mg/100 mL | −0.02 [−0.46; 0.43] | −0.36 [−1.88; 1.16] | −0.77 [−12.12; 10.58] | −8.93 [−20.82; 2.96] | −5.99 [−20.19; 8.21] | −2.48 [−5.60; 0.63] |

| HbA1c, % | −0.01 [−0.02; 0.01] | 0.01 [−0.04; 0.05] | 0.01 [−0.30; 0.33] | −0.24 [−0.57; 0.09] | −0.06 [−0.46; 0.33] | −0.05 [−0.13; 0.04] |

| Triglycerides, mg/100 mL | 0.15 [−0.98; 1.27] | −0.66 [−4.32; 3.00] | 15.37 [−11.26; 42.00] | 23.88 [−4.44; 52.21] | 4.72 [−29.53; 38.96] | −5.90 [−13.34; 1.56] |

| Triglycerides-glucose index, a.u. | 0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] | −0.01 [−0.04; 0.03] | 0.08 [−0.20; 0.36] | 0.12 [−0.18; 0.42] | 0.06 [−0.30; 0.41] | −0.10 [−0.18; −0.02] * |

| Total cholesterol, mg/100 mL | 0.14 [−0.51; 0.78] | −0.74 [−2.92; 1.44] | 3.80 [−12.53; 20.13] | −1.40 [−19.04; 16.23] | 11.23 [−9.12; 31.59] | −2.98 [−7.47; 1.51] |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/100 mL | −0.06 [−0.24; 0.12] | 0.22 [−0.37; 0.81] | −1.45 [−5.97; 3.07] | −3.26 [−7.91; 1.40] | −0.16 [−5.90; 5.59] | 0.66 [−0.57; 1.90] |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/100 mL | 0.27 [−0.30; 0.84] | −0.74 [−2.55; 1.06] | 5.36 [−8.26; 18.98] | −3.75 [−18.22; 10.72] | 15.75 [−0.86; 32.36] | −1.82 [−5.57; 1.93] |

| Parameters related to mental health | ||||||

| Well-being, score | - | - | −0.39 [−8.47; 7.69] | −0.97 [−9.67; 7.73] | 1.82 [−8.37; 12.00] | - |

| Stress, score | - | - | 1.70 [−0.62; 4.02] | 1.37 [−1.17; 3.90] | 1.69 [−1.28; 4.65] | - |

| Parameters Related to Mental Health | Eating Behaviors | Diet Quality, Score B [95%CI] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-Being, Score B [95%CI] | Stress, Score B [95%CI] | Emotional Eating, Score B [95%CI] | Uncontrolled Eating, Score B [95%CI] | Cognitive Restraint, Score B [95%CI] | ||

| Adiposity parameters | ||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.10 [−0.19; −0.02] * | 0.15 [−0.03; 0.33] | 3.63 [2.25; 5.01] *** | 3.65 [1.47; 5.84] *** | 0.66 [−1.48; 2.79] | −0.95 [−1.57; −0.33] ** |

| Body fat, % | −0.18 [−0.32; −0.04] * | 0.24 [−0.06; 0.53] | 5.75 [3.46; 8.03] *** | 5.56 [1.95; 9.17] ** | 1.85 [−1.63; 5.33] | −1.56 [−2.57; −0.55] ** |

| Waist circumference, cm | −0.21 [−0.38; −0.04] * | 0.24 [−0.14; 0.61] | 6.89 [3.96; 9.82] *** | 6.93 [2.39; 11.48] ** | 1.13 [−3.33; 5.59] | −1.80 [−3.11; −0.50] ** |

| Hip circumference, cm | −0.21 [−0.37; −0.04] * | 0.43 [0.07; 0.78] * | 6.59 [3.75; 9.43] *** | 6.70 [2.31; 11.10] ** | 0.63 [−3.69; 4.94] | −1.61 [−2.88; −0.35] * |

| Waist-hip, ratio, a.u. | −0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] | −0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] | 0.02 [0.01; 0.03] * | 0.02 [−0.01; 0.04] | 0.01 [−0.02; 0.03] | −0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] |

| Diet quality, score | 0.01 [−0.02; 0.04] | −0.01 [−0.08; 0.06] | −0.43 [−1.02; 0.16] | −0.58 [−1.43; 0.28] | −0.55 [−1.33; 0.23] | − |

| Biochemical parameters | ||||||

| Glucose, mg/100 mL | −0.11 [−0.23; 0.01] | 0.16 [−0.09; 0.41] | 3.33 [1.27; 5.39] ** | 3.03 [−0.08; 6.14] | −1.75 [−4.63; 1.14] | 0.48 [−0.36; 1.32] |

| HbA1c, % | 0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] | 0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] | 0.07 [−0.01; 0.14] | 0.03 [−0.07; 0.14] | −0.11 [−0.20; −0.02] * | −0.02 [ −0.05; 0.01] |

| Triglycerides, mg/100 mL | −0.07 [−0.68; 0.54] | 0.41 [−0.88; 1.69] | 13.97 [3.12; 24.82] * | 19.14 [3.34; 34.93] * | 4.36 [−10.60; 19.32] | −0.75 [−5.06; 3.57] |

| Triglycerides-glucose index, a.u. | −0.01 [−0.01; 0.01] | 0.01 [−0.01; 0.02] | 0.22 [0.08; 0.35] ** | 0.30 [0.11; 0.50] ** | 0.01 [−0.18; −0.21] | −0.01 [−0.06; 0.05] |

| Total cholesterol, mg/100 mL | 0.30 [−0.15; 0.75] | −0.26 [−1.22; 0.71] | 5.42 [−2.99; 13.83] | 11.49 [−0.54; 23.52] | −5.78 [−16.96; 5.40] | 0.23 [−3.02; 3.47] |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/100 mL | 0.30 [0.12; 0.48] *** | −0.47 [−0.87; −0.07] * | −3.67 [−7.24; −0.10] * | −2.66 [−7.95; 2.62] | −0.38 [−5.74; 4.97] | 0.88 [−0.54; 2.30] |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/100 mL | 0.01 [−0.38; 0.40] | 0.10 [−0.75; 0.94] | 5.44 [−1.91; 12.80] | 10.03 [−0.51; 20.57] | −7.80 [−18.52; 2.91] | −0.50 [−3.38; 2.38] |

| Parameters related to mental health | ||||||

| Well-being, score | - | - | −7.45 [−11.41; −3.49] *** | −8.02 [−14.00; −2.04] ** | −2.61 [−8.30; 3.08] | - |

| Stress, score | - | - | 3.07 [1.16; 4.99] ** | 1.14 [−1.81; 4.10] | 0.69 [−2.01; 3.39] | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Diez-Hernández, M.; Parilli-Moser, I.; Zerón-Rugerio, M.F.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Emotional and Uncontrolled Eating Mediate the Well-Being–Adiposity Relationship in Women but Not in Men. Nutrients 2026, 18, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010111

Diez-Hernández M, Parilli-Moser I, Zerón-Rugerio MF, Izquierdo-Pulido M. Emotional and Uncontrolled Eating Mediate the Well-Being–Adiposity Relationship in Women but Not in Men. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010111

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiez-Hernández, Maria, Isabella Parilli-Moser, María Fernanda Zerón-Rugerio, and Maria Izquierdo-Pulido. 2026. "Emotional and Uncontrolled Eating Mediate the Well-Being–Adiposity Relationship in Women but Not in Men" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010111

APA StyleDiez-Hernández, M., Parilli-Moser, I., Zerón-Rugerio, M. F., & Izquierdo-Pulido, M. (2026). Emotional and Uncontrolled Eating Mediate the Well-Being–Adiposity Relationship in Women but Not in Men. Nutrients, 18(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010111