Evaluating the Need for Pre-CoMiSS™, a Parent-Specific Cow’s Milk-Related Symptom Score: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

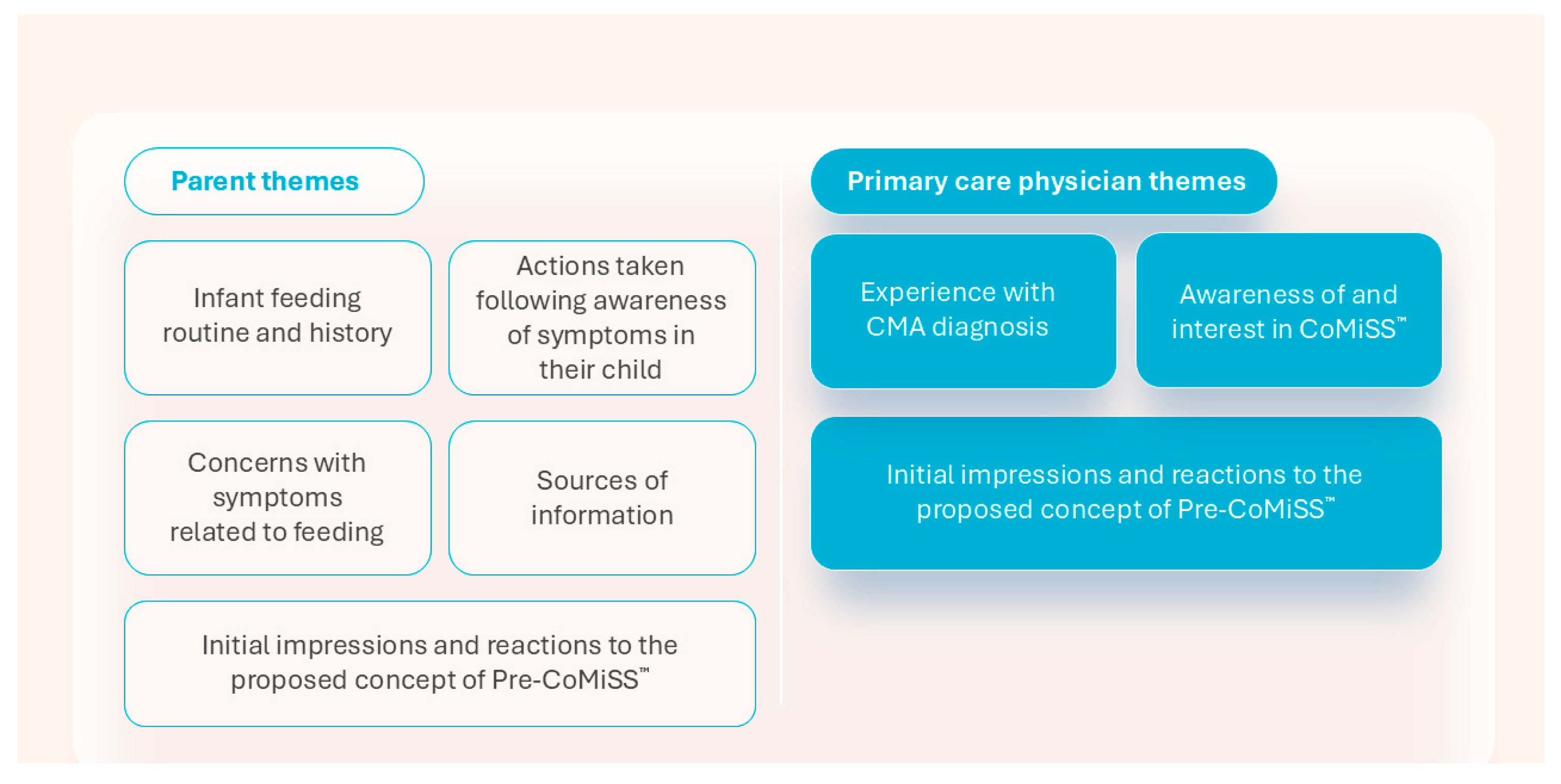

3.1. Interviews, Participants, and Themes

3.2. Parent Themes

3.2.1. Theme 1: Infant Feeding Routine and History

“Once we added [infant formula], we noticed reflux, spitting and changes in poop but we were told to wait it out as this is part of changing phase”.(Parent, male, Germany, child’s age: 6 months)

“We noticed a few changes when we started her on formula so I did a bit of Googling and you end up going down a wormhole!”(Parent, male, UK, child’s age: 4 months)

“When I realized that my son was not gaining weight, I went to my local pharmacy to confirm it. I knew there was something wrong with his food”.(Parent, female, Spain, child’s age: 3 months)

“I was more worried with my first kid. First kid regurgitated for up to 6 months. Now second born is doing the same thing. First born felt he was regurgitating as much as he was eating, but in fact he was gaining weight”.(Parent, male, Sweden, child’s age: 2 months)

3.2.2. Theme 2: Actions Taken Following Awareness of Symptoms in Their Child

“The paediatric nurse specialist told me babies have an immature digestive system when they’re born so I was reluctant to change brands too much to give him time to get used to things. I’m glad we waited, because it did resolve itself”.(Parent, female, UK, child’s age: 7 months)

“My paediatrician just said to try this formula. Why not, I said. I don’t know any other milk”.(Parent, female, Spain, child’s age: 5 months)

“I thought he would regurgitate less with this formula, but he regurgitates both breast milk and formula milk. Just something about the stomach. Sometimes, I think I could just go back [to him] taking cow’s milk again because I don’t think it has an influence. But I’m gonna wait till the allergy test”.(Parent, female, Sweden, child’s age: 3 months)

“Yeah, some people say, hey, it’s normal, it’s normal, but how normal is it?”(Parent, female, Spain, child’s age: 3 months)

3.2.3. Theme 3: Concerns with Symptoms Related to Feeding

“CMA is one of those things that everybody on my Facebook Mums group has at some point”.(Parent, female, UK, child’s age: 7 months)

“The body will get used to it and with time it will get better (…) We did not talk about it to Doc as we did not have an appt with her and this is normal baby reaction to something new”.(Parent, male, Germany, child’s age: 6 months)

“I thought he would regurgitate less with this formula, but he regurgitates both breast milk and formula milk. Just something about the stomach. Sometimes, I think I could just go back [to him] taking cow’s milk again because I don’t think it has an influence. But I’m going to wait till the allergy test”.(Parent, female, Sweden, child’s age: 3 months)

“I do have a couple of cases of problems with milk formulas in my group of friends”.(Parent, male, Spain, child’s age: 3 months)

3.2.4. Theme 4: Sources of Information

“The NHS website is something that is checked, familiar and simple–it showed us the symptoms of intolerances”.(Parent, male, UK, child’s age: 4 months)

“I also check the brochure that we got at the hospital or at the gynaecologist. On Instagram I follow die_togs to take information and see other people[s’] experiences, etc., and I use an app called Oje, ich wachse!”(Parent, female, Germany, child’s age: 2 months)

“1177 is a page where I search for information. It is reliable! There is also Familjeliv, but it[’s] more parents talking, not experts”.(Parent, male, Sweden, child’s age: 2 months)

3.2.5. Theme 5: Initial Impressions and Reactions to the Proposed Concept of Pre-CoMiSS™

“It’s obviously not diagnostic, it helps clarify if it could be CMA and helps you gather information to go to see your GP”.(Parent, female, UK, child’s age: 7 months)

“This tool just gives you something right away, it helps me during the conversation with the doctor. So you are part of that, you need to be more self-determined in what you want examined”.(Parent, female, Germany, child’s age: 11 months)

“Having these results will help me with the next visit to the doctor; I sometimes forget dates and times and I have to keep a diary”.(Parent, female, Sweden, child’s age: 5 months)

“You have read my mind! This tool is exactly what we have been talking about before (in introduction)!”(Parent, female, Spain, child’s age: 5 months)

3.3. Primary Care Physician Themes

3.3.1. Theme 1: Experience with CMA Diagnosis

“I don’t feel comfortable diagnosing it by myself without a second opinion–we always refer on to Pediatrics in my practice”.(Physician, UK)

“Severe symptoms can be seen almost straight away but less severe ones can take some time to diagnose”.(Physician, Spain)

“The major symptom I look at when I have a baby suffering is the weight of the baby and their skin condition”.(Physician, Germany)

3.3.2. Theme 2: Awareness of and Interest in CoMiSS™

“We use CoMiSS with parents in our surgery (practice); I go through the questions with them, it backs up my decision-making and reassures parents. It can help set their mind at rest that it isn’t CMA”.(Physician, UK)

“I don’t use the score sheet anymore because I know all the symptoms babies could have related to milk”.(Physician, Germany)

“I knew about CoMiSS because they presented it in a medical congress I attended some time ago”.(Physician, Spain)

“This looks like it’s quick and you could easily score this and get it together. This could be helpful for me myself in my own evaluation, but also for the parents…we tell them: these are the things that we look at and we end up here”.(Physician, Sweden)

3.3.3. Theme 3: Initial Impressions and Reactions to the Proposed Concept of Pre-CoMiSS™

“This will allow parents to validate their concerns in a constructive way”.(Physician, UK)

“If I could give it to some parents…but distributing to all kinds of parents, this is not a good idea. Parents feel insecure, you will create fear. Then it will steal your time if diagnosis is not clear, the parent come to you and present it with the tool, then you must take the blood test. It is taking blood in the vein, it is invasive”.(Physician, Germany)

“We only have 15 min per child, so if the child has a problem and the parents have written it down, I don’t need to ask, I could read through; it could be a help even for me”.(Physician, Sweden)

“With this [tool] we can go straight to the point, and I will not have to ask so many questions”.(Physician, Spain)

3.4. Executional Learnings and Optimisation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMA | Cow’s milk allergy |

| CoMiSS | Cow’s Milk-related Symptom Score |

| ESPGHAN | European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| PCP | Primary care physician |

| Pre-CoMiSS | Parent-reported Cow’s Milk-related Symptom Score |

References

- Edwards, C.W.; Younus, M.A. Cow Milk Allergy; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R.; Vandenplas, Y.; Lozinsky, A.C.; Vieira, M.C.; Berni Canani, R.; du Toit, G.; Dupont, C.; Giovannini, M.; Uysal, P.; Cavkaytar, O.; et al. Diagnosis and management of food allergy-induced constipation in young children-An EAACI position paper. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 35, e14163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rona, R.J.; Keil, T.; Summers, C.; Gislason, D.; Zuidmeer, L.; Sodergren, E.; Sigurdardottir, S.T.; Lindner, T.; Goldhahn, K.; Dahlstrom, J.; et al. The prevalence of food allergy: A meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 120, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bognanni, A.; Chu, D.K.; Firmino, R.T.; Arasi, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Agarwal, A.; Dziechciarz, P.; Horvath, A.; Jebai, R.; Mihara, H.; et al. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) guideline update-XIII-Oral immunotherapy for CMA–Systematic review. World Allergy Organ. J. 2022, 15, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, A.A.; Sprikkelman, A.B.; Grimshaw, K.E.; Roberts, G.; Grabenhenrich, L.; Rosenfeld, L.; Siegert, S.; Dubakiene, R.; Rudzeviciene, O.; Reche, M.; et al. Incidence and natural history of challenge-proven cow’s milk allergy in European children--EuroPrevall birth cohort. Allergy 2015, 70, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koletzko, S.; Heine, R.G.; Grimshaw, K.E.; Beyer, K.; Grabenhenrich, L.; Keil, T.; Sprikkelman, A.B.; Roberts, G. Non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy in EuroPrevall. Allergy 2015, 70, 1679–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.I.; Wing, O.; Milkova, D.; Jackson, E.; Li, K.; Bradshaw, L.E.; Wyatt, L.; Haines, R.; Santer, M.; Murphy, A.W.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors for milk allergy overdiagnosis in the BEEP trial cohort. Allergy 2025, 80, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, K.A.; Wood, R.A.; Keet, C.A. Persistent cow’s milk allergy is associated with decreased childhood growth: A longitudinal study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woicka-Kolejwa, K.; Zaczeniuk, M.; Majak, P.; Pawłowska-Iwanicka, K.; Kopka, M.; Stelmach, W.; Jerzyńska, J.; Stelmach, I. Food allergy is associated with recurrent respiratory tract infections during childhood. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2016, 33, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntti, H.; Tikkanen, S.; Kokkonen, J.; Alho, O.P.; Niinimäki, A. Cow’s milk allergy is associated with recurrent otitis media during childhood. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999, 119, 867–873. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Q.Y. Risk factors for chronic and recurrent otitis media—A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocerino, R.; Aquilone, G.; Stea, S.; Rea, T.; Simeone, S.; Carucci, L.; Coppola, S.; Berni Canani, R. The Burden of Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy in the Pediatric Age: A Systematic Review of Costs and Challenges. Healthcare 2025, 13, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, C.M.; Agrawal, A.; Gandhi, D.; Gupta, R.S. The US population-level burden of cow’s milk allergy. World Allergy Organ. J. 2022, 15, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, R.; Venter, C.; Bognanni, A.; Szajewska, H.; Shamir, R.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Fiocchi, A.; Vandenplas, Y.; WAO DRACMA Guideline Group. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) Guideline update-VII-Milk elimination and reintroduction in the diagnostic process of cow’s milk allergy. World Allergy Organ. J. 2023, 16, 100785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, J.A.; Assa’ad, A.; Burks, A.W.; Jones, S.M.; Sampson, H.A.; Wood, R.A.; Plaut, M.; Cooper, S.F.; Fenton, M.J.; Arshad, S.H.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: Report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, S1–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyt, D.; Ball, H.; Makwana, N.; Green, M.R.; Bravin, K.; Nasser, S.M.; Clark, A.T.; Standards of Care Committee (SOCC) of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI). BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk allergy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2014, 44, 642–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koletzko, S.; Niggemann, B.; Arato, A.; Dias, J.A.; Heuschkel, R.; Husby, S.; Mearin, M.L.; Papadopoulou, A.; Ruemmele, F.M.; Staiano, A.; et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow’s-milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 55, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraro, A.; de Silva, D.; Halken, S.; Worm, M.; Khaleva, E.; Arasi, S.; Dunn-Galvin, A.; Nwaru, B.I.; De Jong, N.W.; Rodriguez Del Rio, P.; et al. Managing food allergy: GA(2)LEN guideline 2022. World Allergy Organ. J. 2022, 15, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Meyer, R.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Salvatore, S.; Venter, C.; Vieira, M.C. The Remaining Challenge to Diagnose and Manage Cow’s Milk Allergy: An Opinion Paper to Daily Clinical Practice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Beltagi, M.; Saeed, N.K.; Bediwy, A.S.; Elbeltagi, R. Cow’s milk-induced gastrointestinal disorders: From infancy to adulthood. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2022, 11, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladkevicius, E.; Nagy, E.; Lack, G.; Guest, J.F. Resource implications and budget impact of managing cow milk allergy in the UK. J. Med. Econ. 2010, 13, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Belohlavkova, S.; Enninger, A.; Frühauf, P.; Makwana, N.; Järvi, A. How Are Infants Suspected to Have Cow’s Milk Allergy Managed? A Real World Study Report. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaferio, L.; Caimmi, D.; Verga, M.C.; Palladino, V.; Trove, L.; Giordano, P.; Verduci, E.; Miniello, V.L. May Failure to Thrive in Infants Be a Clinical Marker for the Early Diagnosis of Cow’s Milk Allergy? Nutrients 2020, 12, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebar-Lozinsky, A.; De Koker, C.; Dziubak, R.; Rolnik, D.L.; Godwin, H.; Dominguez-Ortega, G.; Skrapac, A.K.; Gholmie, Y.; Reeve, K.; Shah, N.; et al. Assessing Feeding Difficulties in Children Presenting with Non-IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Allergies-A Commonly Reported Problem. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galip, N.; Ünsel, M. The Use of Internet for Allergic Diseases: Which One is the First Step: Specialists or Google? Cyprus J. Med. Sci. 2022, 7, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.; Vandenplas, Y.; Reese, I.; Vieira, M.C.; Ortiz-Piedrahita, C.; Walsh, J.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Chebar Lozinsky, A.; Fox, A.; Chakravarti, V.; et al. The role of online symptom questionnaires to support the diagnosis of cow’s milk allergy in children for healthcare professionals—A Delphi consensus study. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 34, e13975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Dupont, C.; Eigenmann, P.; Host, A.; Kuitunen, M.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shah, N.; Shamir, R.; Staiano, A.; Szajewska, H.; et al. A workshop report on the development of the Cow’s Milk-related Symptom Score awareness tool for young children. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Bajerova, K.; Dupont, C.; Eigenmann, P.; Kuitunen, M.; Meyer, R.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Salvatore, S.; Shamir, R.; Szajewska, H. The Cow’s Milk Related Symptom Score: The 2022 Update. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajerova, K.; Salvatore, S.; Dupont, C.; Eigenmann, P.; Kuitunen, M.; Meyer, R.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Szajewska, H.; Vandenplas, Y. The Cow’s Milk-Related Symptom Score (CoMiSSTM): A Useful Awareness Tool. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Carvajal, E.; Peeters, S.; Balduck, N.; Jaddioui, Y.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Huysentruyt, K. The Cow’s Milk-Related Symptom Score (CoMiSSTM): Health Care Professional and Parent and Day-to-Day Variability. Nutrients 2020, 12, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, V.; Netting, M.J.; Volders, E.; Palmer, D.J.; WAO DRACMA Guideline Group. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) guidelines update-X-Breastfeeding a baby with cow’s milk allergy. World Allergy Organ. J. 2023, 16, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, A.K.; Flessner, C.A. Examining Differences in Parent Knowledge About Pediatric Food Allergies. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2020, 45, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, S.; Rabaiah, R.; Dweikat, A.; Abu-Ali, L.; Yaeesh, H.; Jbour, R.; Al-Jabi, S.W.; Zyoud, S.H. Parental knowledge and attitudes toward food allergies: A cross-sectional study on determinants and educational needs. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, G.R.; Faria, D.P.B.; Zihlmann, K.F.; Speridiao, P. Attitudes and practice of caregivers for cow’s milk allergy according to stages of behavior change. Rev. Paul Pediatr. 2022, 40, e2021133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpio-Escalona, L.V.; Gonzalez-de-Olano, D. Use of the Internet by patients attending allergy clinics and its potential as a tool that better meets patients’ needs. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 1064–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Perea, A.; Cabrera-Freitag, P.; Fuentes-Aparicio, V.; Infante, S.; Zapatero, L.; Zubeldia, J.M. Social Media as a Tool for the Management of Food Allergy in Children. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 28, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandracchia, F.; Llaurado, E.; Tarro, L.; Valls, R.M.; Sola, R. Mobile Phone Apps for Food Allergies or Intolerances in App Stores: Systematic Search and Quality Assessment Using the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e18339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulhas Çelik, I.; Buyuktiryaki, B.; Civelek, E.; Kocabas, C.N. Internet Use Habits of Parents with Children Suffering from Food Allergy. Asthma Allergy Immunol. 2019, 17, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Grbich, C.; Kemp, A. Parental food allergy information needs: A qualitative study. Arch. Dis. Child 2007, 92, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangler, J.; Jansky, M. Online enquiries and health concerns—A survey of German general practitioners regarding experiences and strategies in patient care. J. Public Health 2024, 32, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce, A.; Dalgıç, B.; Çullu-Çokuğraş, F.; Çokuğraş, H.; Kansu, A.; Alptekin-Sarıoğlu, A.; Şekerel, B.E. Cow’s milk protein allergy awareness and practice among Turkish pediatricians: A questionnaire-survey. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2017, 59, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrazo, J.A.; Alrefaee, F.; Chakrabarty, A.; de Leon, J.C.; Geng, L.; Gong, S.; Heine, R.G.; Jarvi, A.; Ngamphaiboon, J.; Ong, C.; et al. International Cross-Sectional Survey among Healthcare Professionals on the Management of Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy and Lactose Intolerance in Infants and Children. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2022, 25, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, C.; Altınel, N.; Shipar, V.; Birgül, K.; Bülbül, L.; Hatipoğlu, N.; Hatipoğlu, S. Evaluation of the Knowledge of Cow’s Milk Allergy among Pediatricians. Sisli. Etfal. Hastan Tip. Bul. 2019, 53, 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Lozinsky, A.C.; Meyer, R.; Anagnostou, K.; Dziubak, R.; Reeve, K.; Godwin, H.; Fox, A.T.; Shah, N. Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy from Diagnosis to Management: A Very Different Journey for General Practitioners and Parents. Children 2015, 2, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubb, C.; Foran, H. Online Health Information Seeking by Parents for Their Children: Systematic Review and Agenda for Further Research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skranes, L.P.; Løhaugen, G.C.C.; Skranes, J. A child health information website developed by physicians: The impact of use on perceived parental anxiety and competence of Norwegian mothers. J. Public Health 2015, 23, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Allen, H.I.; Campbell, D.E.; Arntsen, K.F.; Simpson, M.R.; Boyle, R.J. Trends in use of specialized formula for managing cow’s milk allergy in young children. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2022, 52, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.C.; Guimarães, T.C.; Silva, R.M.; Cheik, M.F.; de Ramos Nápolis, A.C.; Barbosa, E.; Silva, G.; Segundo, G.R. Prevalence of food allergy in infants and pre-schoolers in Brazil. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2016, 44, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.; Delaney, M.; Dive-Pouletty, C. The Health Economic Impact of Managing CMPA According to Guidelines: Challenging Current Treatment Practise in the UK. Value Health 2016, 19, A550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Fehring, L.; Kinscher, K.; Truebel, H.; Dahlhausen, F.; Ehlers, J.P.; Mondritzki, T.; Boehme, P. Perspective of German medical faculties on digitization in the healthcare sector and its influence on the curriculum. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2021, 38, Doc124. [Google Scholar]

| Physician | Country | Gender | Years Practicing | Workplace |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Sweden | Male | 18 | Private clinic |

| H2 | Sweden | Female | 14 | Healthcare centre |

| H3 | Sweden | Female | 9 | Healthcare centre |

| H4 | Sweden | Male | 35 | Healthcare centre |

| H5 | UK | Female | 12 | Individual NHS practice |

| H6 | UK | Female | 7 | Group NHS practice/community GP |

| H7 | UK | Male | 30 | Individual NHS practice |

| H8 | UK | Female | 20 | Group NHS practice/community GP |

| H9 | UK | Male | 16 | Group NHS practice/community GP |

| H10 | UK | Female | 8 | Individual NHS practice |

| H11 | Spain | Female | 13 | Children’s healthcare centre |

| H12 | Spain | Female | 29 | Children’s healthcare centre |

| H13 | Spain | Male | 26 | Children’s healthcare centre |

| H14 | Spain | Female | 25 | Children’s healthcare centre |

| H15 | Germany | Female | 19 | Group private practice |

| H16 | Germany | Female | 23 | Group private practice |

| H17 | Germany | Male | 9 | Private practice |

| H18 | Germany | Male | 26 | Private practice |

| Parent | Country | Gender | Age (Years) | Birth Order of Child | Child’s Age (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Sweden | Male | 28 | Second | 2 |

| P2 | Sweden | Female | 39 | Third | 10 |

| P3 | Sweden | Male | 42 | First | 3 |

| P4 | Sweden | Female | 36 | Third | 7 |

| P5 | Sweden | Female | 25 | First | 3 |

| P6 | Sweden | Female | 40 | First | 4 |

| P7 | UK | Female | 29 | First | 7 |

| P8 | UK | Male | 31 | First | 4 |

| P9 | UK | Female | 39 | Second | 3 |

| P10 | UK | Female | 35 | First | 6 |

| P11 | UK | Female | 35 | First | 6 |

| P12 | UK | Female | 41 | Second | 7 |

| P13 | UK | Male | 34 | First | 5 |

| P14 | UK | Male | 35 | First | 4 |

| P15 | Spain | Female | 32 | Second | 10 |

| P16 | Spain | Male | 37 | First | 3 |

| P17 | Spain | Female | 38 | Second | 5 |

| P18 | Spain | Female | 30 | First | 9 |

| P19 | Spain | Female | 28 | First | 3 |

| P20 | Spain | Male | 37 | First | 6 |

| P21 | Germany | Female | 30 | First | 10 |

| P22 | Germany | Male | 41 | First | 2 |

| P23 | Germany | Female | 34 | Second | 11 |

| P24 | Germany | Female | 29 | Second | 7 |

| P25 | Germany | Female | 32 | First | 2 |

| P26 | Germany | Male | 35 | Second | 6 |

| Theme | Summary | Key Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant feeding routine and history | All parents undertook a similar process of observing mild symptoms following the introduction of cow’s milk-based formula, tracking progress then seeking advice, with no immediate recourse to the physician. | UK and Germany |

|

| Sweden and Spain |

| ||

| Actions taken following awareness of symptoms in their child | All parents reported speaking to their primary care physician at their next scheduled visit if symptoms persisted. | UK and Germany |

|

| Sweden and Spain |

| ||

| Concerns with symptoms related to feeding | The level of awareness for CMA and attitudes varied among parents. | UK and Spain |

|

| Germany and Sweden |

| ||

| Sources of information | Varied sources of information were used by parents. | UK |

|

| Sweden |

| ||

| Germany |

| ||

| Spain |

| ||

| Initial impressions and reactions to the proposed concept of Pre-CoMiSS™ |

| ||

| Theme | Summary | Key Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experience with CMA diagnosis | Most physicians were very aware of CMA and confident in their knowledge and ability to identify and treat CMA. All physicians reported seeing many suspected or mild cases, but most had little or no experience with severe CMA cases. The diagnostic protocol for CMA was largely the same in all countries, with a detailed history being routinely taken to rule out other conditions. | UK |

|

| Germany |

| ||

| Sweden |

| ||

| Spain |

| ||

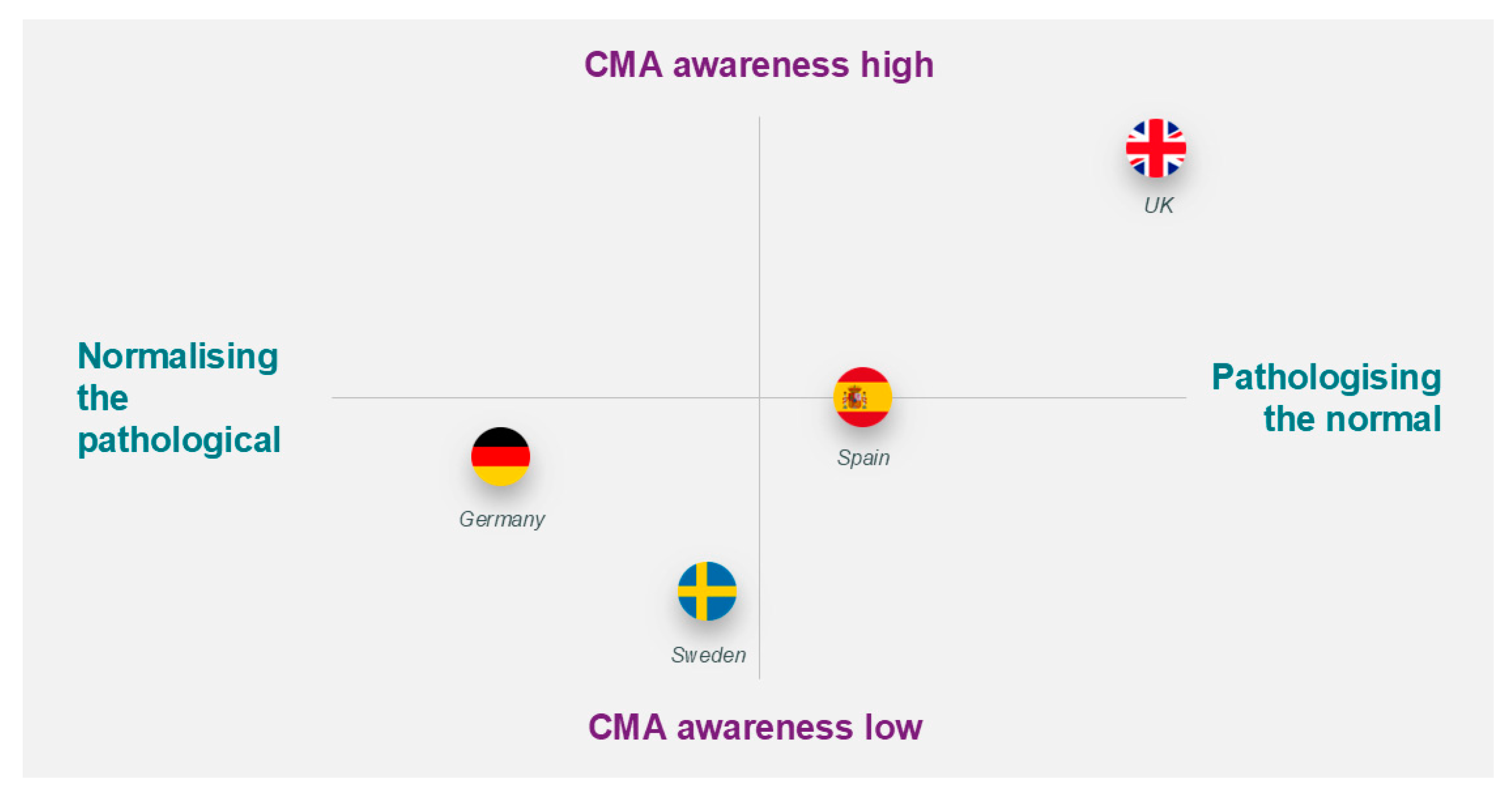

| Awareness of and interest in CoMiSS™ | Awareness of CoMiSS™ was high in the UK and Spain and low in Germany and Sweden. Interest in CoMiSS™ was high in the UK, Spain, and Sweden but low in Germany. | UK |

|

| Germany |

| ||

| Sweden |

| ||

| Spain |

| ||

| Initial impressions and reactions to the proposed concept of Pre-CoMiSS™ | The concept was very positively received by physicians in the UK, Spain, and Sweden, but German physicians had some concerns. | UK, Sweden and Spain |

|

| Germany |

| ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vandenplas, Y.; Bajerová, K.; Dupont, C.; Kuitunen, M.; Meyer, R.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Salvatore, S.; Shamir, R.; Staiano, A.; et al. Evaluating the Need for Pre-CoMiSS™, a Parent-Specific Cow’s Milk-Related Symptom Score: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091563

Vandenplas Y, Bajerová K, Dupont C, Kuitunen M, Meyer R, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Ribes-Koninckx C, Salvatore S, Shamir R, Staiano A, et al. Evaluating the Need for Pre-CoMiSS™, a Parent-Specific Cow’s Milk-Related Symptom Score: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(9):1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091563

Chicago/Turabian StyleVandenplas, Yvan, Kateřina Bajerová, Christophe Dupont, Mikael Kuitunen, Rosan Meyer, Anna Nowak-Wegrzyn, Carmen Ribes-Koninckx, Silvia Salvatore, Raanan Shamir, Annamaria Staiano, and et al. 2025. "Evaluating the Need for Pre-CoMiSS™, a Parent-Specific Cow’s Milk-Related Symptom Score: A Qualitative Study" Nutrients 17, no. 9: 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091563

APA StyleVandenplas, Y., Bajerová, K., Dupont, C., Kuitunen, M., Meyer, R., Nowak-Wegrzyn, A., Ribes-Koninckx, C., Salvatore, S., Shamir, R., Staiano, A., Szajewska, H., Venter, C., Jones, S., Järvi, A., & Couchepin, C. (2025). Evaluating the Need for Pre-CoMiSS™, a Parent-Specific Cow’s Milk-Related Symptom Score: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients, 17(9), 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091563