Polish Consumers’ Attachment to Meat: Food and Plant-Based Meat Alternative Choices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Collection

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample

3.2. Characteristics of the Identified Clusters

3.3. Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Declared Changes in Meat and Plant Food Consumption, Taking into Account Identified Clusters

3.4. Characteristics of the Identified Clusters with Regard to Self-Identity

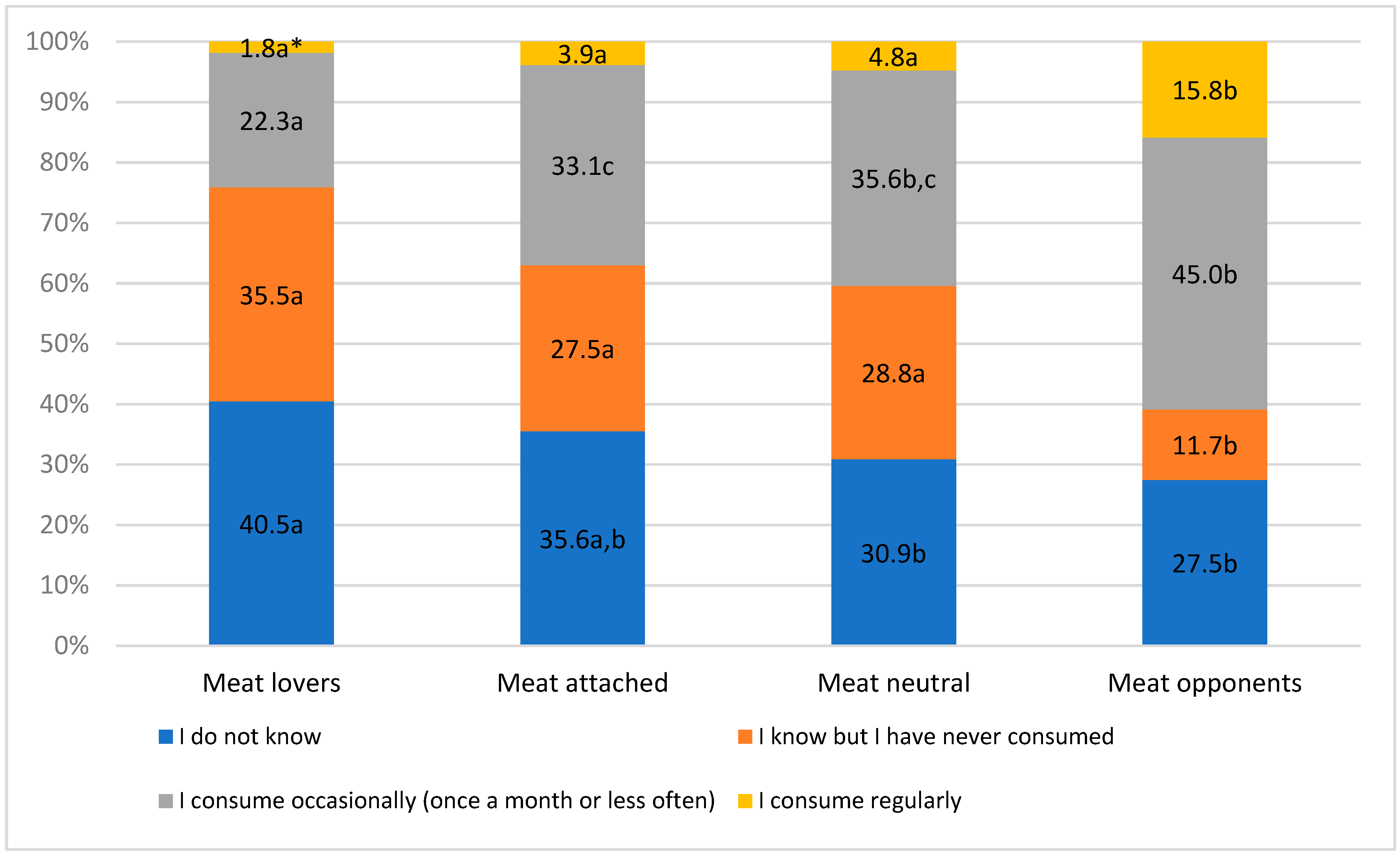

3.5. Perception of Plant-Based Meat Alternatives with Regard to Identified Clusters

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruxton, C.H.S.; Gordon, S. Animal board invited review: The contribution of red meat to adult nutrition and health beyond protein. Animal 2024, 18, 101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ederer, P.; Leroy, F. The societal role of meat—What the science says. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Smith, N.W.; Adesogan, A.T.; Beal, T.; Iannotti, L.; Moughan, P.J.; Mann, N. The role of meat in the human diet: Evolutionary aspects and nutritional value. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.D. Meat composition and nutritional value. In Lawrie’ s Meat Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 635–659. [Google Scholar]

- Kunachowicz, H.; Nadolna, I.; Iwanow, K.; Przygoda, B. Wartość Odżywcza Wybranych Produktów Spożywczych i Typowych Potraw; Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; ISBN 8320044448. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, R.S.; Imran, A.; Hussain, M.B. Nutritional composition of meat. Meat Sci. Nutr. 2018, 61, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Astrup, A.; Magkos, F.; Bier, D.M.; Brenna, J.T.; de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Hill, J.O.; King, J.C.; Mente, A.; Ordovas, J.M.; Volek, J.S. Saturated fats and health: A reassessment and proposal for food-based recommendations: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Bhowmik, S.; Afreen, M.; Ucak, I.; Ikram, A.; Gerini, F.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Ayivi, R.D.; Castro-Munoz, R. Bodybuilders and high-level meat consumers’ behavior towards rabbit, beef, chicken, turkey, and lamb meat: A comparative review. Nutrition 2024, 119, 112305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, A.; Lee, E.-Y.; Ncho, C.M.; Kim, C.-J.; Son, Y.-M.; Hwang, Y.-H.; Joo, S.-T. Quality characteristics of meat analogs through the incorporation of textured vegetable protein: A systematic review. Foods 2022, 11, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Jiao, J.; Wu, F.; Mao, L.; Zhang, Y. Associations of meat consumption and changes with all-cause mortality in hypertensive patients during 11.4-year follow-up: Findings from a population-based nationwide cohort. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Leip, A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcorta, A.; Porta, A.; Tárrega, A.; Alvarez, M.D.; Vaquero, M.P. Foods for plant-based diets: Challenges and innovations. Foods 2021, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Hwang, Y.-H.; Joo, S.-T. Meat analog as future food: A review. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2020, 62, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Trivedi, N.; Enamala, M.K.; Kuppam, C.; Parikh, P.; Nikolova, M.P.; Chavali, M. Plant-based meat analogue (PBMA) as a sustainable food: A concise review. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 2499–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldello, A.; Giampieri, F.; De Giuseppe, R.; Grosso, G.; Baroni, L.; Battino, M. The rise of processed meat alternatives: A narrative review of the manufacturing, composition, nutritional profile and health effects of newer sources of protein, and their place in healthier diets. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 127, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, D.; Tseng, T.W.; Swartz, E. The business of cultured meat. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Moura, M.B.M.V.; Teixeira, C.S.S.; Costa, J.; Mafra, I. Monitoring Yellow Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) as a Potential Novel Allergenic Food: Effect of Food Processing and Matrix. Nutrients 2023, 15, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurek, M.A.; Onopiuk, A.; Pogorzelska-Nowicka, E.; Szpicer, A.; Zalewska, M.; Półtorak, A. Novel protein sources for applications in meat-alternative products—Insight and challenges. Foods 2022, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font-i-Furnols, M.; Guerrero, L. An overview of drivers and emotions of meat consumption. Meat Sci. 2025, 219, 109619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallström, E.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A.; Börjesson, P. Environmental impact of dietary change: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitzmann, C. Vegetarian nutrition: Past, present, future. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 496S–502S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej-Skalska, A.; Matysiak, B.; Grudziński, M. Mięso wieprzowe a zdrowie człowieka. Kosmos 2016, 65, 535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Pouzou, J.G.; Zagmutt, F.J. Guidelines to restrict consumption of red meat to under 350 g/wk based on colorectal cancer risk are not consistent with health evidence. Nutrition 2024, 122, 112395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruby, M.B. Vegetarianism. A blossoming field of study. Appetite 2012, 58, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, N.R.; Xiang, N.; Kaplan, D.L. Plant-based and cell-based approaches to meat production. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolnicka, K. Talerz Zdrowego Żywienia; Narodowe Centrum Edukacji Żywieniowej: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Evans, N.M.; Liu, H.; Shao, S. A review of research on plant-based meat alternatives: Driving forces, history, manufacturing, and consumer attitudes. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2639–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusz, R.; Smetana, S.; Wiktor, A.; Parniakov, O.; Pobiega, K.; Rybak, K.; Nowacka, M. The selected quality aspects of infrared-dried black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) and yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) larvae pre-treated by pulsed electric field. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 80, 103085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, S.T.; Davis, T.; Papies, E.K. Increasing the appeal of plant-based foods through describing the consumption experience: A data-driven procedure. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 119, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual models of food choice: Influential factors related to foods, individual differences, and society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circus, V.E.; Robison, R. Exploring perceptions of sustainable proteins and meat attachment. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Godinho, C.A.; Truninger, M. Reducing meat consumption and following plant-based diets: Current evidence and future directions to inform integrated transitions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Oliveira, A.; Calheiros, M.M. Meat, beyond the plate. Data-driven hypotheses for understanding consumer willingness to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 90, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lentz, G.; Connelly, S.; Mirosa, M.; Jowett, T. Gauging attitudes and behaviours: Meat consumption and potential reduction. Appetite 2018, 127, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Attached to meat? (Un)Willingness and intentions to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 95, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021–2030; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vural, Y.; Ferriday, D.; Rogers, P.J. Consumers’ attitudes towards alternatives to conventional meat products: Expectations about taste and satisfaction, and the role of disgust. Appetite 2023, 181, 106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, J.; Olsen, A. Meat reduction in 5 to 8 years old children—A survey to investigate the role of parental meat attachment. Foods 2021, 10, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Öström, Å.; Mihnea, M.; Niimi, J. Consumers’ attachment to meat: Association between sensory properties and preferences for plant-based meat alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 116, 105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, E.; Semmler, C.; Bray, H.; Ankeny, R.A.; Chur-Hansen, A. Neutralising the meat paradox: Cognitive dissonance, gender, and eating animals. Appetite 2018, 123, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, A.; Baune, M.-C.; Smetana, S.; Bornkessel, S.; Broucke, K.; Van Royen, G.; Enneking, U.; Weiss, J.; Heinz, V.; Hieke, S. Preferences of german consumers for meat products blended with plant-based proteins. Sustainability 2021, 13, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczebyło, A.; Halicka, E.; Rejman, K.; Kaczorowska, J. Is eating less meat possible? Exploring the willingness to reduce meat consumption among millennials working in polish cities. Foods 2022, 11, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusiak, B.; Szymkowiak, A.; Kucharska, B.; Gálová, J.; Mravcová, A. Predictors of intention to reduce meat consumption due to environmental reasons—Results from Poland and Slovakia. Meat Sci. 2022, 184, 108674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, W.; Górska-Warsewicz, H.; Kulykovets, O. Meat, meat products and seafood as sources of energy and nutrients in the average polish diet. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, J.; Aiking, H. Prospects for pro-environmental protein consumption in Europe: Cultural, culinary, economic and psychological factors. Appetite 2018, 121, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaş, N.; Jaeger, B. Changes in attitudes toward meat consumption after chatting with a large language model. Soc. Influ. 2025, 20, 2475802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaapila, A.; Michel, F.; Jouppila, K.; Sontag-Strohm, T.; Piironen, V. Millennials’ consumption of and attitudes toward meat and plant-based meat alternatives by consumer segment in Finland. Foods 2022, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, F.; Jaworski, M. Kuchnia polska jako element uatrakcyjnienia oferty turystycznej. Zesz. Nauk. Uczel. Vistula 2017, 54, 112–124. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek, R. Sektor mięsa czerwonego i drobiowego w Polsce w okresie ostatnich turbulencji rynkowych. Przem. Spożywczy 2023, 77, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.; Norwood, F.B.; Lusk, J.L. Are consumers wilfully ignorant about animal welfare. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Yearbooks of Agriculture. 2024. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/portalinformacyjny/en/defaultaktualnosci/3328/6/19/1/statistical_yearbook_of_agriculture_2024_2.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- De Backer, C.; Erreygers, S.; De Cort, C.; Vandermoere, F.; Dhoest, A.; Vrinten, J.; Van Bauwel, S. Meat and masculinities. Can differences in masculinity predict meat consumption, intentions to reduce meat and attitudes towards vegetarians? Appetite 2020, 147, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harguess, J.M.; Crespo, N.C.; Hong, M.Y. Strategies to reduce meat consumption: A systematic literature review of experimental studies. Appetite 2020, 144, 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuszczki, E.; Boakye, F.; Zielińska, M.; Dereń, K.; Bartosiewicz, A.; Oleksy, Ł.; Stolarczyk, A. Vegan diet: Nutritional components, implementation, and effects on adults’ health. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1294497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielkema, M.H.; Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J. Veg on the menu? Differences in menu design interventions to increase vegetarian food choice between meat-reducers and non-reducers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 102, 104675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Van Loo, E.J.; Gellynck, X.; Verbeke, W. Flemish consumer attitudes towards more sustainable food choices. Appetite 2013, 62, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoker, E.N.; van der Linden, S. Fleshing out the theory of planned of behavior: Meat consumption as an environmentally significant behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llauger, M.; Claret, A.; Bou, R.; López-Mas, L.; Guerrero, L. Consumer attitudes toward consumption of meat products containing offal and offal extracts. Foods 2021, 10, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Health Belief Model. In Encyclopedia of Psychology; Kazdin, A.E., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; Volume 4, pp. 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska-Chmielewska, A. Produkcja i spożycie mięsa w Polsce na tle UE i świata w latach 2000–2022. Przegląd Zach. 2023, 386, 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; De Houwer, J.; Geuens, M.; Slabbinck, H.; Spruyt, A.; Van Kerckhove, A.; Van Lippevelde, W.; De Steur, H.; Verbeke, W. Environmentally sustainable food consumption: A review and research agenda from a goal-directed perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohlmann, A. Lowering barriers to plant-based diets: The effect of human and non-human animal self-similarity on meat avoidance intent and sensory food satisfaction. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, G.; Wassmann, B. To imitate or not to imitate? How consumers perceive animal origin products and plant-based alternatives imitating minimally processed vs ultra-processed food. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 472, 143447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagevos, H.; Verbeke, W. Meat consumption and flexitarianism in the Low Countries. Meat Sci. 2022, 192, 108894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, R.B.; MacDonnell Mesler, R.; Montford, W.J.; Chernishenko, J. This meat or that alternative? How masculinity stress influences food choice when goals are conflicted. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1111681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deliza, R.; Lima, M.F.; Ares, G. Rethinking sugar reduction in processed foods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 40, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, M.; Wilson, M.S. A dual-process motivational model of attitudes towards vegetarians and vegans. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, S.; Furchheim, P.; Strässner, A.-M. Plant-based meat alternatives: Motivational adoption barriers and solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soteras, T.; Szerman, N.; Merayo, M.; Vaudagna, S.R.; Denoya, G.I.; Guerrero, L.; Galmarini, M.V. Are Argentinians ready for plant-based meat alternatives? A case study on awareness and willingness for consumption. Appetite 2025, 206, 107817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.P.; Saget, S.; Zimmermann, B.; Petig, E.; Angenendt, E.; Rees, R.M.; Chadwick, D.; Gibbons, J.; Shrestha, S.; Williams, M. Environmental and land use consequences of replacing milk and beef with plant-based alternatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 424, 138826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linville, T.; Hanson, K.L.; Sobal, J. Hunting and raising livestock are associated with meat-related attitudes, norms and frequent consumption: Implications for dietary guidance to rural residents. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 3067–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarmino, E.; Leonetti, M.; Abdul-Rahaman, S. What exactly does a “plant-based diet” mean to rural residents? Results of a mixed-methods inquiry. In Proceedings of the Rural Sociological Society Annual Meeting, Burlington, VT, USA, 2–6 August 2023; pp. 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, S.K. Ideological bases of attitudes towards meat abstention: Vegetarianism as a threat to the cultural and economic status quo. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2022, 25, 1534–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, R.; Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M. Elderly perception of distance to the grocery store as a reason for feeling food insecurity—Can food policy limit this? Nutrients 2020, 12, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfiyya, M.N.; Chang, L.F.; Lipsky, M.S. A cross-sectional study of US rural adults’ consumption of fruits and vegetables: Do they consume at least five servings daily? BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rune, C.J.B.; Song, Q.; Clausen, M.P.; Giacalone, D. Consumer perception of plant-based burger recipes studied by projective mapping. Future Foods 2022, 6, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieke, S.-D.; Erhard, A.; Stetkiewicz, S. Do ingredients matter? Exploring consumer preference for abstract vs. concrete descriptors of plant-based meat and dairy alternatives. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, B.L.; Boom, R.M.; van der Goot, A.J. Structuring processes for meat analogues. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 81, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Clausen, M.P.; Jaeger, S.R. Understanding barriers to consumption of plant-based foods and beverages: Insights from sensory and consumer science. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.R.H.; Onwezen, M.C.; van der Meer, M. Consumer perceptions of different protein alternatives. In Meat and Meat Replacements; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 333–362. [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Consumer acceptance of novel food technologies. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, E.S.; Oberrauter, L.-M.; Normann, A.; Norman, C.; Svensson, M.; Niimi, J.; Bergman, P. Identifying barriers to decreasing meat consumption and increasing acceptance of meat substitutes among Swedish consumers. Appetite 2021, 167, 105643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, J.A.; Benson-Rea, M.; Young, J.; Seifert, M. Cutting down or eating up: Examining meat consumption, reduction, and sustainable food beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, R.E.; Kim, B.F.; Goldman, S.E.; Dutkiewicz, J.; Biehl, E.; Bloem, M.W.; Neff, R.A.; Nachman, K.E. Considering plant-based meat substitutes and cell-based meats: A public health and food systems perspective. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 569383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, P.; Rössel, J.; Scholz, M. Motivations and constraints of meat avoidance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonera, A.; Svanes, E.; Bugge, A.B.; Hatlebakk, M.M.; Prexl, K.-M.; Ueland, Ø. Moving consumers along the innovation adoption curve: A new approach to accelerate the shift toward a more sustainable diet. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukid, F. Plant-based meat analogues: From niche to mainstream. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, M.; Bowles, S.; Lynn, A.; Paxman, J.R. Novel plant-based meat alternatives: Future opportunities and health considerations. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 82, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoek, A.C.; Luning, P.A.; Weijzen, P.; Engels, W.; Kok, F.J.; De Graaf, C. Replacement of meat by meat substitutes. A survey on person-and product-related factors in consumer acceptance. Appetite 2011, 56, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, F.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Gantriis, R.F.; Fraga, P.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A. Plant-based food and protein trend from a business perspective: Markets, consumers, and the challenges and opportunities in the future. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 3119–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szenderak, J.; Frona, D.; Rakos, M. Consumer acceptance of plant-based meat substitutes: A narrative review. Foods 2022, 11, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzerman, J.E.; Van Boekel, M.A.J.S.; Luning, P.A. Exploring meat substitutes: Consumer experiences and contextual factors. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, M.; Kinchla, A.J.; Nolden, A.A. Role of sensory evaluation in consumer acceptance of plant-based meat analogs and meat extenders: A scoping review. Foods 2020, 9, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röös, E.; de Groote, A.; Stephan, A. Meat tastes good, legumes are healthy and meat substitutes are still strange—The practice of protein consumption among Swedish consumers. Appetite 2022, 174, 106002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdiarmid, J.I. The food system and climate change: Are plant-based diets becoming unhealthy and less environmentally sustainable? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sadig, R.; Wu, J. Are novel plant-based meat alternatives the healthier choice? Food Res. Int. 2024, 183, 114184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | ||

|---|---|---|

| N * | % | |

| Total | 1003 | 100.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 483 | 48.2 |

| Women | 520 | 51.8 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 104 | 10.4 |

| 25–34 | 193 | 19.2 |

| 35–44 | 205 | 20.4 |

| 45–54 | 162 | 16.2 |

| 55–64 | 221 | 22.0 |

| 65 and above | 118 | 11.8 |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 100 | 10.0 |

| Vocational | 180 | 17.9 |

| Secondary | 403 | 40.2 |

| Higher | 320 | 31.9 |

| Place of residence before studying | ||

| A village | 377 | 37.6 |

| A town with less than 20,000 inhabitants | 139 | 13.9 |

| A city with 20,000–100,000 inhabitants | 187 | 18.6 |

| A city with 100,00–200,000 inhabitants | 104 | 10.4 |

| A city with 200,000–500,000 inhabitants | 93 | 9.3 |

| A city with over 500,000 inhabitants | 103 | 10.3 |

| Self-reported financial situation We have enough for everything without any special savings | 170 | 16.9 |

| We live frugally and we have enough money for everything | 377 | 37.6 |

| We live very frugally to save for major purchases | 269 | 26.8 |

| We have only enough money for the cheapest food and clothes | 88 | 8.8 |

| We have enough money only for the cheapest food but not for clothes | 41 | 4.1 |

| We do not have enough money even for the most inexpensive food and clothes | 13 | 1.3 |

| I do not know/hard to say | 45 | 4.5 |

| Age (mean; SD in years) (range) | 45.4; 15.55 (18–83) | |

| Total (N = 1003) | Cluster 1 (N = 220) | Cluster 2 (N = 379) | Cluster 3 (N = 284) | Cluster 4 (N = 120) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meat Attachment | Hedonism | 3.5 (0.98) * | 4.7 a (0.37) ** | 3.1 c (0.54) | 3.8 b (0.47) | 1.8 d (0.60) | <0001 |

| Entitlement | 3.7 (0.93) | 4.8 a (0.34) | 3.3 c (0.56) | 3.9 b (0.46) | 2.3 d (0.79) | <0001 | |

| Affinity | 2.3 (0.95) | 1.4 c (0.62) | 2.9 a (0.61) | 1.8 b (0.54) | 3.0 a (0.98) | <0001 | |

| Dependence | 3.2 (0.77) | 4.1 a (0.36) | 3.0 c (0.53) | 3.3 b (0.47) | 1.9 d (0.44) | <0001 |

| Items | Total Sample (N = 1003) | C1 Meat Lovers (N = 220) | C2 Meat-Neutral (N = 379) | C3 Meat-Attached (N = 284) | C4 Meat Opponents (N = 120) | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men Women | 48.2 51.8 | 63.2 36.8 | 42.2 57.8 | 49.3 50.7 | 36.7 63.3 | <0.001 |

| Education | Primary Vocational Secondary Higher | 10.0 17.9 40.2 31.9 | 12.3 16.4 44.5 26.8 | 9.0 21.9 36.9 32.2 | 8.5 15.1 45.1 31.3 | 12.5 15.0 30.8 41.7 | 0.017 |

| Place of residence | A village A town with less than 20,000 inhabitants A city with 20,000–100,000 inhabitants A city with 100,00–200,000 inhabitants A city with 200,000–500,000 inhabitants A city with over 500,000 inhabitants | 37.6 13.9 18.6 10.4 9.3 10.3 | 30.5 14.1 25.5 11.4 10.5 8.2 | 40.4 16.4 15.3 10.5 9.0 8.4 | 40.5 12.7 18.0 8.8 9.1 10.9 | 35.0 8.3 18.3 11.7 8.3 18.3 | 0.018 |

| Intention to eat more plant-based foods in the next year | Yes No | 60.4 39.6 | 31.8 68.2 | 74.1 25.9 | 52.5 47.5 | 88.3 11.7 | <0.001 |

| Intention to eat less meat and meat products in the next year | Yes No | 42.1 57.9 | 9.1 90.9 | 60.2 39.8 | 26.4 73.6 | 82.5 17.5 | <0.001 |

| I Consider Myself to Be a Person Who | Total Sample (N = 1003) | C1 Meat Lovers (N = 220) | C2 Meat Neutral (N = 379) | C3 Meat Attached (N = 284) | C4 Meat Opponents (N = 120) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cares about my health | 3.7 (0.94) * | 3.9 a ** (0.97) | 3.7 ab (0.87) | 3.7 ab (0.87) | 3.6 b (1.20) | 0.032 |

| Draws attention to the naturalness of food | 3.6 (1.00) | 3.5 b (1.19) | 3.6 ab (0.84) | 3.5 ab (0.97) | 3.7 a (1.12) | 0.037 |

| Likes to buy new food products | 3.5 (1.06) | 3.7 a (1.18) | 3.4 b (0.96) | 3.6 ab (0.97) | 3.3 b (1.27) | 0.019 |

| Seeks information about new food products | 2.9 (1.18) | 2.8 b (1.32) | 3.1 a (1.04) | 2.9 b (1.17) | 2.7 b (1.24) | 0.000 |

| Likes to eat products from different countries | 3.7 (1.06) | 3.9 a (1.18) | 3.6 b (0.92) | 3.7 b (1.04) | 3.6 b (1.23) | 0.005 |

| Is afraid to eat foods I have never tried | 2.8 (1.15) | 2.8 ab (1.34) | 3.0 a (0.97) | 2.7 b (1.10) | 2.4 c (1.30) | <0001 |

| Plant-Based Meat Alternatives | People Who Consume Plant-Based Meat Alternatives (N = 384) | C1 Meat Lovers (N = 53) | C2 Meat-Neutral (N = 153) | C3 Meat-Attached (N = 105) | C4 Meat Opponents (N = 73) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taste the same as animal products | 2.7 (1.14) * | 2.1 c ** (1.27) | 3.0 a (0.98) | 2.5 b (1.09) | 2.7 ab (1.24) | <0.0001 |

| Resemble animal products in appearance | 3.5 (0.96) | 3.3 a (1.23) | 3.6 a (0.82) | 3.5 a (0.87) | 3.6 a (1.12) | 0.041 |

| Have the same nutritional value as animal products | 3.2 (1.07) | 2.6 b (1.25) | 3.4 a (0.95) | 2.9 b (0.95) | 3.6 a (1.07) | <0.0001 |

| Are more expensive than animal products | 3.7 (1.06) | 3.6 ab (1.23) | 3.6 ab (0.98) | 3.9 a (0.98) | 3.5 b (1.14) | 0.0302 |

| Are more convenient to use when I am preparing a dish at home | 3.5 (0.96) | 3.0 c (1.17) | 3.6 b (0.87) | 3.4 b (0.84) | 3.8 a (0.98) | <0.0001 |

| Reduce the time I have to spend preparing a dish | 3.2 (1.02) | 2.8 a (1.14) | 3.3 ab (0.94) | 3.1 bc (0.87) | 3.5 a (1.15) | 0.0003 |

| Are beneficial to me for health reasons | 3.7 (1.00) | 2.9 d (1.28) | 3.8 b (0.86) | 3.5 c (0.83) | 4.1 a (0.93) | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosicka-Gębska, M.; Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Sajdakowska, M.; Gębski, J.; Gutkowska, K. Polish Consumers’ Attachment to Meat: Food and Plant-Based Meat Alternative Choices. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081332

Kosicka-Gębska M, Jeżewska-Zychowicz M, Sajdakowska M, Gębski J, Gutkowska K. Polish Consumers’ Attachment to Meat: Food and Plant-Based Meat Alternative Choices. Nutrients. 2025; 17(8):1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081332

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosicka-Gębska, Małgorzata, Marzena Jeżewska-Zychowicz, Marta Sajdakowska, Jerzy Gębski, and Krystyna Gutkowska. 2025. "Polish Consumers’ Attachment to Meat: Food and Plant-Based Meat Alternative Choices" Nutrients 17, no. 8: 1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081332

APA StyleKosicka-Gębska, M., Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M., Sajdakowska, M., Gębski, J., & Gutkowska, K. (2025). Polish Consumers’ Attachment to Meat: Food and Plant-Based Meat Alternative Choices. Nutrients, 17(8), 1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081332