Barriers and Enablers of Healthy Eating Among University Students in Oaxaca de Juarez: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

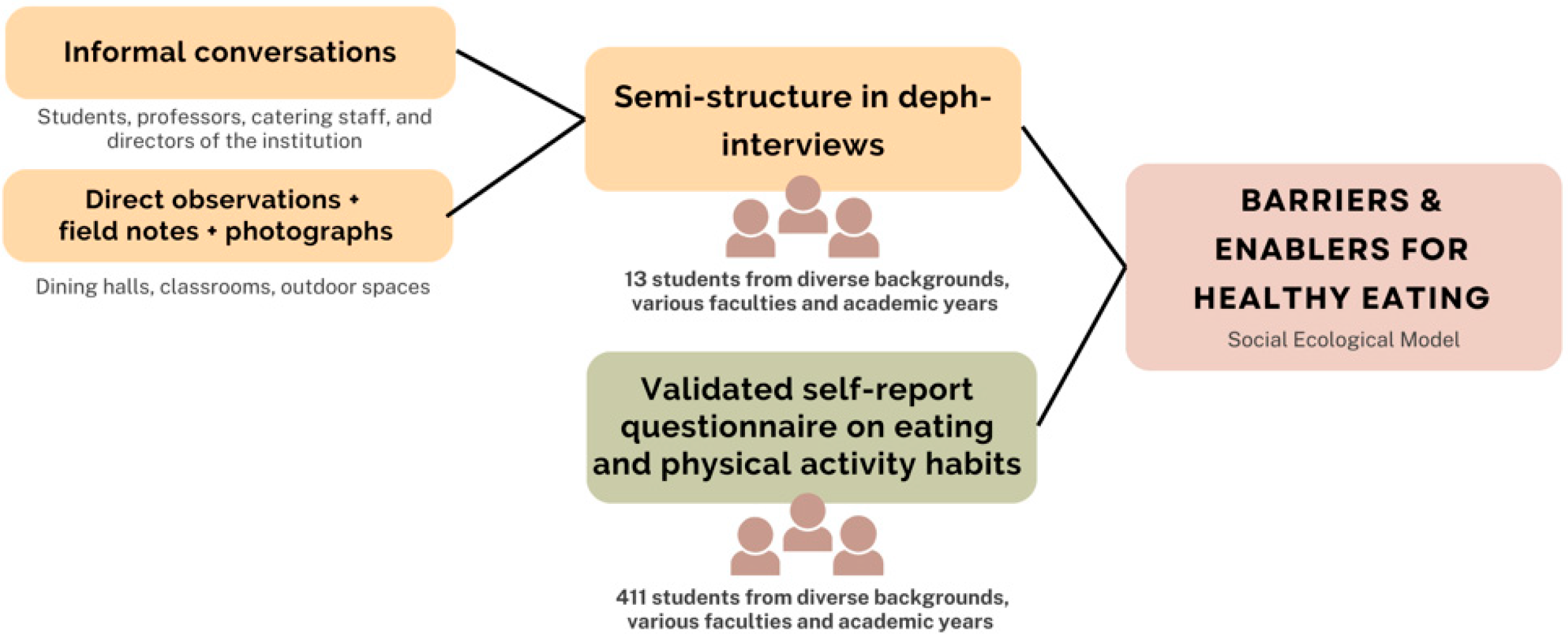

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Study Procedures and Data Collection

2.3.1. Ethnography Methods

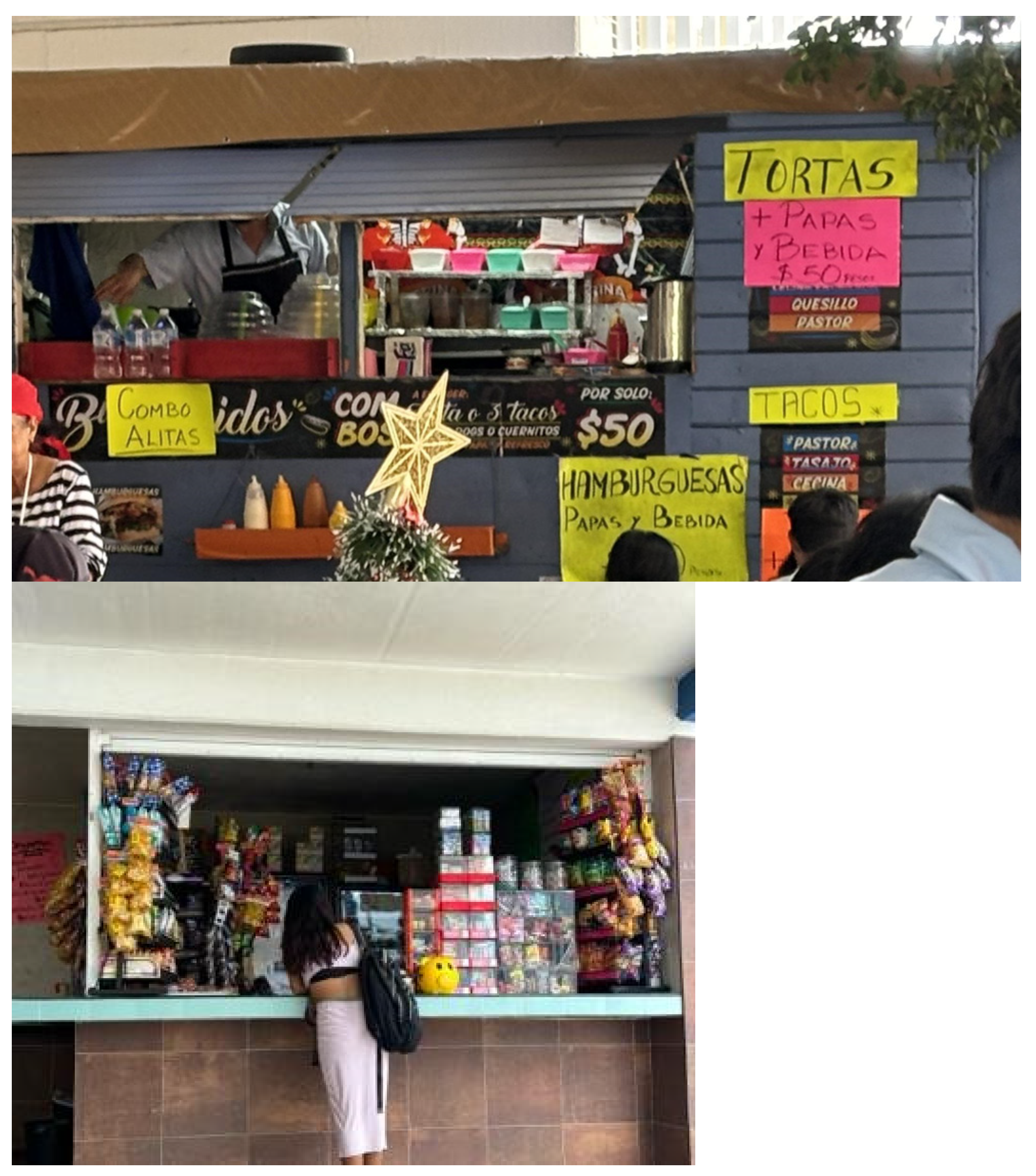

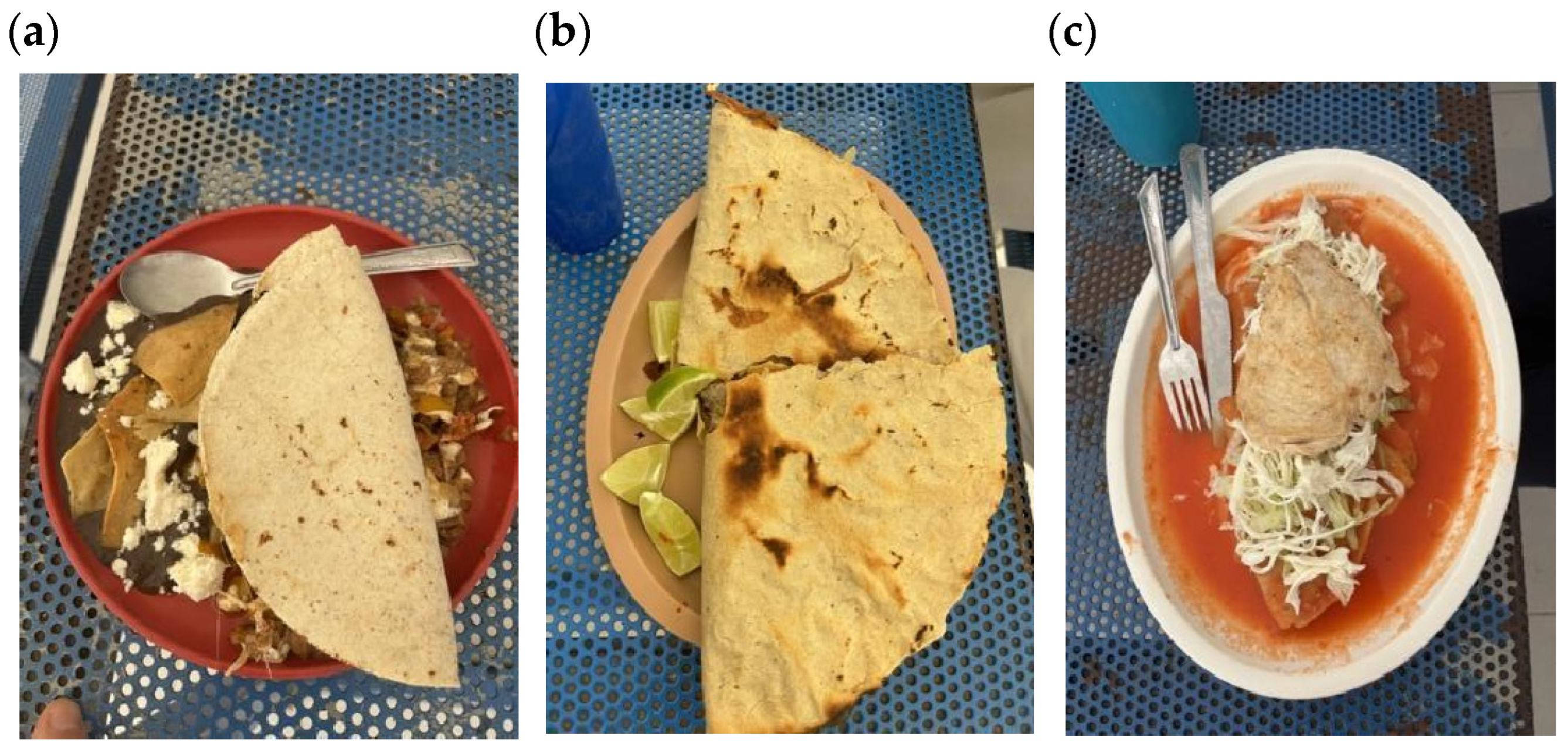

Direct Observations, Field Notes, and Digital Photographs

Informal Conversations with Participants in Natural Settings

Semi-Structured Interviews

2.3.2. Validated Self-Report Questionnaire on Eating and Physical Activity Habits

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.1.1. Semi-Structured Interview Participants

3.1.2. Questionnaire Participants

3.2. Dietary Patterns

3.2.1. Key Staples Among University Students

3.2.2. Vegetable Consumption Frequency

3.2.3. Fruit Consumption Frequency

3.2.4. Beverage Consumption

3.2.5. Processed Food and Snack Consumption

3.2.6. Dining Locations and Social Dining

3.2.7. Physical Activity

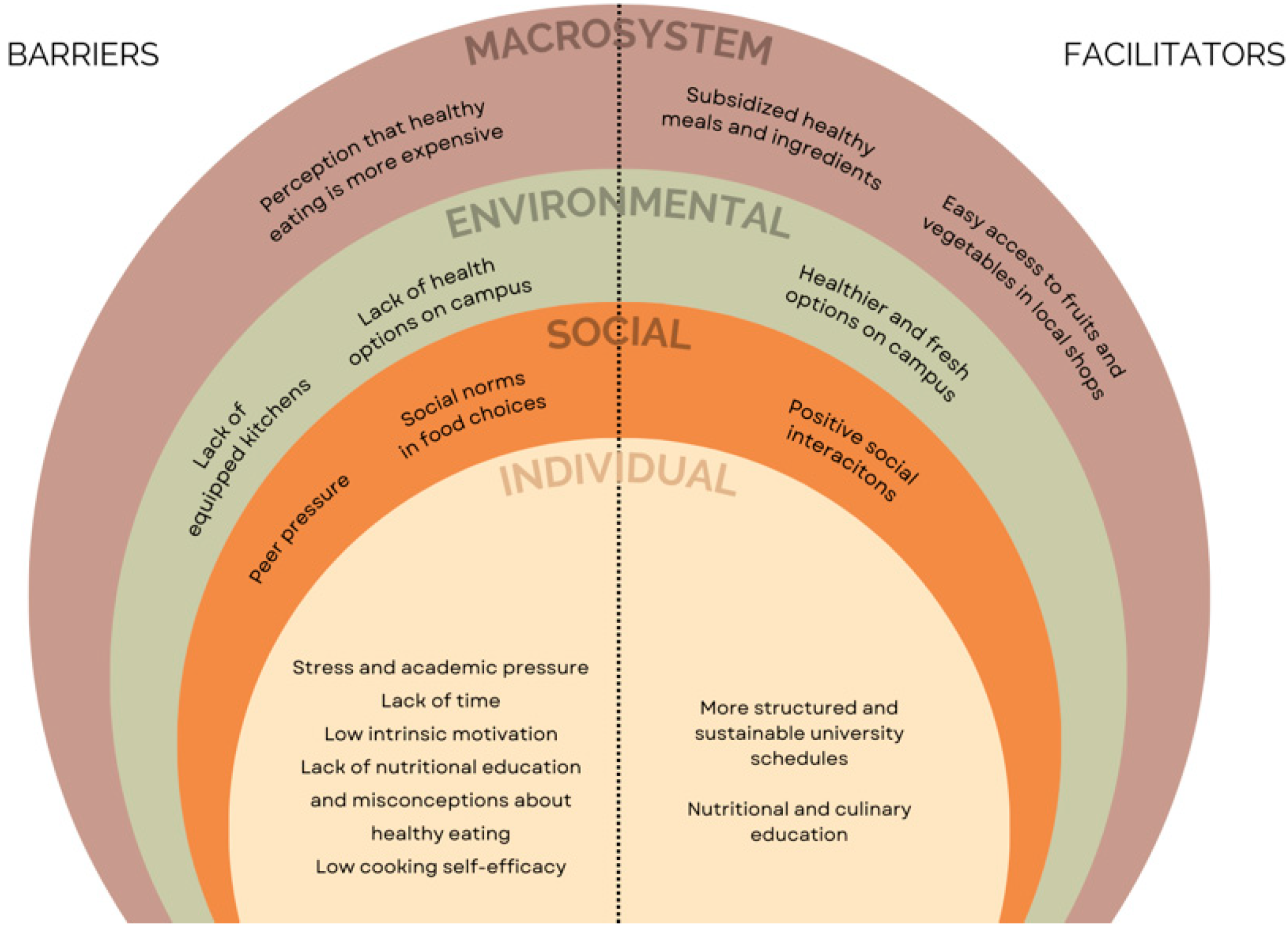

3.3. Determinants for Healthy Eating

3.3.1. Individual Factors

Individual Barriers

- Stress and academic pressure

- Lack of time

- Low intrinsic motivation

- Lack of nutritional education and misconceptions about healthy eating

- Low cooking self-efficacy

Individual Enablers

- More structured and sustainable university schedules

- Nutritional and culinary education

3.3.2. Environmental Social Factors

Environmental Social Barriers

- Peer pressure

- Social norms in food choices

Environmental Social Enablers

- Positive social interactions

3.3.3. Physical Environmental Factors

Physical Environmental Barriers

- Lack of healthy options on campus

- Lack of equipped kitchens

Physical Environmental Enablers

- Healthier and fresher options on campus

3.3.4. Macrosystem Factors

Macrosystem Barriers

- Perception that healthy eating is more expensive

Macrosystem Enablers

- Subsidized healthy meals and fruits and vegetables

- Easy access to affordable fruits and vegetables in local shops

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raghoebar, S.; Mesch, A.; Gulikers, J.; Winkens, L.H.H.; Wesselink, R.; Haveman-Nies, A. Experts’ perceptions on motivators and barriers of healthy and sustainable dietary behaviors among adolescents: The SWITCH project. Appetite 2024, 194, 107196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vadeboncoeur, C.; Townsend, N.; Foster, C. A meta-analysis of weight gain in first year university students: Is freshman 15 a myth? BMC Obes. 2015, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Petersen, J.D.; Lin, L.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Ji, G.; Zhang, F. A qualitative study of food sociality in three provinces of South China: Social functions of food and dietary behavior. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1058764. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1058764/full (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- León, E.; Tabares, M.; Baile, J.I.; Salazar, J.G.; Zepeda, A.P. Eating behaviors associated with weight gain among university students worldwide and treatment interventions: A systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 72, 1624–1631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Landry, M.J.; Hagedorn-Hatfield, R.L.; Zigmont, V.A. Barriers to college student food access: A scoping review examining policies, systems, and the environment. J. Nutr. Sci. 2024, 13, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino-Rosales, D.; Lopez-Moro, A.; Heras-González, L.; Jimenez-Casquet, M.J.; Olea-Serrano, F.; Mariscal-Arcas, M. Estimation of the Quality of the Diet of Mexican University Students Using DQI-I. Healthcare 2023, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Nonato, I.; Galván-Valencia, O.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Oviedo-Solís, C.; Barquera, S. Prevalencia de obesidad y factores de riesgo asociados en adultos mexicanos: Resultados de la Ensanut 2022. Salud Publica Mex. 2023, 65, S238–S247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, M.A.; Lazarevich, I.; Tolentino, R.G.; Arias, M.Á.M.; Alva, G.L.; Vázquez, C.C.R. Construct Validity of a Questionnaire on Eating and Physical Activity Habits for Adolescents in Mexico City. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan-Portillo, M.; Sánchez, E.; Cárdenas-Cárdenas, L.M.; Karam, R.; Claudio, L.; Cruz, M.; Burguete-García, A.I. Dietary patterns in Mexican children and adolescents: Characterization and relation with socioeconomic and home environment factors. Appetite 2018, 121, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Bravo, C.; Gómez-Cruz, Z.; Núñez-Hernández, A.; Landeros-Ramírez, P. Eating habits in students of a University Campus in Jalisco, Mexico. Rev. Educ. Básica 2022, 6, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, S.L.; García, D.I.M.; Toledo, S.L.; García, D.I.M. Cambios en el consumo alimentario en el sur de México: Efectos del aislamiento por COVID-19. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2023, 73, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K.; Elder-Robinson, E.; Howard, K.; Garvey, G. A Systematic Methods Review of Photovoice Research with Indigenous Young People. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231172076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, F.X. Sustainable Food Systems in Culturally Coherent Social Contexts: Discussions Around Culture, Sustainability, Climate Change and the Mediterranean Diet. In Climate Change-Resilient Agriculture and Agroforestry: Ecosystem Services and Sustainability; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, J.; Olawuyi, Y.; Opara, I.; Ifafore, M. Hindrances and Enablers of Healthy Eating Behavior Among College Students in an HBCU: A Qualitative Study. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, L.; Buchthal, O.V.; Banna, J.C. Identifying perceived barriers and enablers of healthy eating in college students in Hawai’i: A qualitative study using focus groups. BMC Nutr. 2019, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, G.L.; Jomori, M.M.; Fernandes, A.C.; Proença, R.P.d.C. Food intake of university students. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 30, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, T.; Ford, B.; Pike, D.; Bryce, R.; Richardson, C.; Wolfson, J.A. Development and implementation of a community health centre-based cooking skills intervention in Detroit, MI. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Gonzalez, P.; Xavier Medina, F.; Bach-Faig, A. Barriers to home food preparation and healthy eating among university students in Catalonia. Appetite 2024, 194, 107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, E.D. Emotional Eating in College Students: Associations with Coping and Healthy Eating Motivators and Barriers. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2024, 31, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eck, K.M.; Quick, V.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Body Dissatisfaction, Eating Styles, Weight-Related Behaviors, and Health among Young Women in the United States. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Toral, M.; Rodríguez-Reinado, C.; Ramallo-Espinosa, A.; Andrés-Villas, M. “It’s Important but, on What Level?”: Healthy Cooking Meanings and Barriers to Healthy Eating among University Students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, K.E.; Cargas, S.; Walsh-Dilley, M.; Mechler, H. Basic Needs Insecurities Are Associated with Anxiety, Depression, and Poor Health Among University Students in the State of New Mexico. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, C.D.; Gomez-Lara, A.; Hee, A.; Shankar, A.; Song, N.; Campos, M.; McCoin, M.; Matias, S.L. Impact of a Food Skills Course with a Teaching Kitchen on Dietary and Cooking Self-Efficacy and Behaviors among College Students. Nutrients 2024, 16, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, J.; Martínez, A.; Nazar, G.; Mosso, C.; Del-Muro, L. Creencias alimentarias en estudiantes universitarios mexicanos: Una aproximación cualitativa. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2019, 46, 727–734. [Google Scholar]

- Almoraie, N.M.; Alothmani, N.M.; Alomari, W.D.; Al-amoudi, A.H. Addressing nutritional issues and eating behaviours among university students: A narrative review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2024, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliens, T.; Clarys, P.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B. Determinants of eating behaviour in university students: A qualitative study using focus group discussions. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharczuk, A.J.; Oliver, T.L.; Dowdell, E.B. Social media’s influence on adolescents′ food choices: A mixed studies systematic literature review. Appetite 2022, 168, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, A.; Jayasingh, S.; Shaik, S. Social Media Influence on Students’ Knowledge Sharing and Learning: An Empirical Study. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Hernandez, M.E. Correlation of executive functions, academic achievement, eating behavior and eating habits in university students of Mexico City. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1268302. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/education/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1268302/full (accessed on 2 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Marian, M.; Pérez, R.L.; McClain, A.C.; Hurst, S.; Reed, E.; Barker, K.M.; Lundgren, R. Nutritional knowledge and practices of low-income women during pregnancy: A qualitative study in two Oaxacan cities. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Novotny, I.P.; Tittonell, P.; Fuentes-Ponce, M.H.; López-Ridaura, S.; Rossing, W.A.H. The importance of the traditional milpa in food security and nutritional self-sufficiency in the highlands of Oaxaca, Mexico. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, J.; Evans, E.H.; O’brien, N.; Moynihan, P.J.; Meyer, T.D.; Adamson, A.J.; Errington, L.; Sniehotta, F.F.; White, M.; Mathers, J.C. Association of behaviour change techniques with effectiveness of dietary interventions among adults of retirement age: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, N.; Hassan, S.S.S.; Abdelmagid, M.; Ali, S.N.M. Learning from the Perspectives of Albert Bandura and Abdullah Nashih Ulwan: Implications towards the 21st Century Education. Din. Ilmu. 2020, 20, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D.H.; DiBenedetto, M.K. Social cognitive theory, self-efficacy, and students with disabilities: Implications for students with learning disabilities, reading disabilities, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In Handbook of Educational Psychology and Students with Special Needs; Educational Psychology Handbook Series; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 243–261. [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo, P.; Prescott, M.P. Assessing the Use of Social Cognitive Theory Components in Cooking and Food Skills Interventions. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, E.C.; Marcovitch, H.; Wolfson, J.A.; Leighton, M.; Peterson, K.E.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M.; Cantoral, A.; Roberts, E.F. Exploring Dietary Patterns in a Mexican Adolescent Population: A Mixed Methods Approach. Appetite 2020, 147, 104542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, S.S.; Haisma, H. Fulfilling food practices: Applying the capability approach to ethnographic research in the Northern Netherlands. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noy, C. Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, N.; McCurdy, S.A.; Markham, C.M. University students’ perception of their dietary behavior through the course of the COVID-19 pandemic: A phenomenological approach. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Al Samman, H.; Marzban, S. Observations on Food Consumption Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Oman. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 779654. [Google Scholar]

- Ottrey, E.; Jong, J.; Porter, J. Ethnography in Nutrition and Dietetics Research: A Systematic Review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1903–1942.e10. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, S.; Kuper, A.; Hodges, B.D. Qualitative research methodologies: Ethnography. BMJ 2008, 337, a1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, M.; Yoneda, K.; Moriyama, M.; Takahashi, S.; Bull, C.; Chaboyer, W. The Dietary Patterns of Japanese Hemodialysis Patients: A Focused Ethnography. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2019, 6, 2333393619878150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.L.; Davis, C.; Downs, S.M.; McLaren, R.; Fanzo, J. A focused ethnographic study on the role of health and sustainability in food choice decisions. Appetite 2021, 165, 105319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, R.K.; Ohnuki-Tierney, E. Anthropology of Food. In The Oxford Handbook of Food History; Pilcher, J.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trundle, C.; Phillips, T. Defining focused ethnography: Disciplinary boundary-work and the imagined divisions between ‘focused’ and ‘traditional’ ethnography in health research—A critical review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 332, 116108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkin, S.; Coomber, R. Value in the Visual: On Public Injecting, Visual Methods and Their Potential for Informing Policy (and Change). Methodol. Innov. Online 2009, 4, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano-Crespo, C.; Rodríguez-Hernández, M.; Cantero-Garlito, P.; Mariano-Juárez, L. Eating Experiences of People with Disabilities: A Qualitative Study in Spain. Healthcare 2020, 8, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menini, A.; Mascarello, G.; Giaretta, M.; Brombin, A.; Marcolin, S.; Personeni, F.; Pinto, A.; Crovato, S. The Critical Role of Consumers in the Prevention of Foodborne Diseases: An Ethnographic Study of Italian Families. Foods 2022, 11, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Caballero, D.; Castillo-Sarmiento, C.A.; Ballesteros-Yánez, I.; Rivero-Jiménez, B.; Mariano-Juárez, L. Microlearning through TikTok in Higher Education. An evaluation of uses and potentials. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 2365–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, J.M.; Spire, Z.D. The Role of Informal Conversations in Generating Data, and the Ethical and Methodological Issues. Forum Qual Sozialforschung Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2020, 21, 11–18. Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/3344 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Swain, J.; King, B. Using Informal Conversations in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221085056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Jiménez, B.; Conde-Caballero, D.; Mariano-Juárez, L. Health and Nutritional Beliefs and Practices among Rural Elderly Population: An Ethnographic Study in Western Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves-Martins, M.; Llauradó, E.; Tarro, L.; Papell-Garcia, I.; Prades-Tena, J.; Kettner-Høeberg, H.; Puiggròs, F.; Arola, L.; Davies, A.; Giralt, M.; et al. “Som la Pera,” a School-Based, Peer-Led Social Marketing Intervention to Engage Spanish Adolescents in a Healthy Lifestyle: A Parallel-Cluster Randomized Controlled Study. Child Obes. 2022, 18, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.I.; Jarrar, A.H.; Abo-El-Enen, M.; Al Shamsi, M.; Al Ashqar, H. Students’ perspectives on promoting healthful food choices from campus vending machines: A qualitative interview study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banna, J.C.; Buchthal, O.V.; Delormier, T.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.M.; Penny, M.E. Influences on eating: A qualitative study of adolescents in a periurban area in Lima, Peru. BMC Public Health 2015, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilger-Kolb, J.; Diehl, K. ‘Oh God, I Have to Eat Something, But Where Can I Get Something Quickly?’—A Qualitative Interview Study on Barriers to Healthy Eating among University Students in Germany. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillet, M.A.; Grouzet, F.M.E. Understanding changes in eating behavior during the transition to university from a self-determination theory perspective: A systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, H.; Watson, T.D.; Slusser, W.; Glik, D.; Rowat, A.C.; Prelip, M. Challenges, Opportunities, and Motivators for Developing and Applying Food Literacy in a University Setting: A Qualitative Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, J. (Ed.) When to Use Focus Groups. In Focus Groups for the Social Science Researcher; Methods for Social Inquiry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 18–39. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/focus-groups-for-the-social-science-researcher/when-to-use-focus-groups/1D26285FB5461733E24047088F483BB7 (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Demant, J. Natural Interactions in Artificial Situations: Focus Groups as an Active Social Experiment. In An Ethnography of Global Landscapes and Corridors; Naidoo, L., Ed.; InTech: Nappanee, IN, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.intechopen.com/books/an-ethnography-of-global-landscapes-and-corridors/natural-interactions-in-artificial-situations-focus-groups-as-an-active-social-experiment- (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Bird, T.; Jensen, T. What’s in the refrigerator? Using an adapted material culture approach to understand health practices and eating habits in the home. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Granada-López, J.M.; Martínez-Abadía, B.; Echániz-Serrano, E.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Jerue, B.A. Factors Related to Diet Quality: A Cross-Sectional Study of 1055 University Students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, B. Atlas.ti for qualitative data analysis. Perspect. Educ. 2002, 20, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-based Dietary Guidelines. Available online: http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/dietary-guidelines/regions/mexico/en/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Hafiz, A.A.; Gallagher, A.M.; Devine, L.; Hill, A.J. University student practices and perceptions on eating behaviours whilst living away from home. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 117, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzal, N.; Kerver, J.M.; Strakovsky, R.S.; Weatherspoon, L.; Alaimo, K. Barriers and facilitators to healthy eating among college students. Nutr. Res. 2025, 133, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, P.K.; Lawler, S.; Durham, J.; Cullerton, K. The food choices of US university students during COVID-19. Appetite 2021, 161, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Davies, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The Association Between Food Insecurity and Dietary Outcomes in University Students: A Systematic Review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 2475–2500.e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sogari, G.; Velez-Argumedo, C.; Gómez, M.I.; Mora, C. College Students and Eating Habits: A Study Using An Ecological Model for Healthy Behavior. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatwan, I.M.; Aljefree, N.M.; Almoraie, N.M. Snacking pattern of college students in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Ravelli, M.N.; Schoeller, D.A. Traditional Self-Reported Dietary Instruments Are Prone to Inaccuracies and New Approaches Are Needed. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 90. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2020.00090/full (accessed on 4 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jick, T.D. Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: Triangulation in Action. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 602–611. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, M.D. Triangulation: A Method to Increase Validity, Reliability, and Legitimation in Clinical Research. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2019, 45, 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- El-Nimr, N.; Bassiouny, S.; Tayel, D. Pattern of Caffeine Consumption Among University Students. J. High Inst. Public Health 2019, 49, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, C.; Weakley, J.; Burke, L.M.; Roach, G.D.; Sargent, C.; Maniar, N.; Townshend, A.; Halson, S.L. The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2023, 69, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharaba, Z.; Sammani, N.; Ashour, S.; Ghemrawi, R.; Al Meslamani, A.Z.; Al-Azayzih, A.; Buabeid, M.A.; Alfoteih, Y. Caffeine Consumption among Various University Students in the UAE, Exploring the Frequencies, Different Sources and Reporting Adverse Effects and Withdrawal Symptoms. J. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 2022, 5762299. [Google Scholar]

- Jabs, J.; Devine, C.M. Time scarcity and food choices: An overview. Appetite 2006, 47, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronk, I.; Kullen, C.; Burdon, C.; O’Connor, H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, D.W.; Mahadevan, M.; Gatto, K.; O’connor, K.; Fissinger, A.; Bailey, D.; Cassara, E. Culinary efficacy: An exploratory study of skills, confidence, and healthy cooking competencies among university students. Perspect. Public Health 2016, 136, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, L.; Alpaugh, M.; Trubek, A.; Skelly, J.; Harvey, J. Beyond Ramen: Investigating Methods to Improve Food Agency among College Students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Young Hong, M. The Effect of Social Cognitive Theory-Based Interventions on Dietary Behavior within Children. J. Nutr. Health Food Sci. 2016, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.K.; Matthews, J.I.; Seabrook, J.A.; Dworatzek, P.D.N. Self-reported food skills of university students. Appetite 2017, 108, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmachu, A.; Heidelberger, L. Exploration of dietary beliefs and social cognitive factors that influence eating habits among college students attending a rural Midwestern university. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Martínez, J.; Cussó-Parcerisas, I.; Carrillo-Álvarez, E. Exploring the barriers and facilitators for following a sustainable diet: A holistic and contextual scoping review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, A.R.; Nelson, S.A.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M. Peer-Led Culinary Skills Intervention for Adolescents: Pilot Study of the Impact on Knowledge, Attitude, and Self-efficacy. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 852–857.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Anderson, E.S.; Winett, R.A.; Wojcik, J.R. Self-regulation, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and social support: Social cognitive theory and nutrition behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 34, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, K.; Ross, H.; Buckley, L.; Lin, B.B. Food in my life: How Australian adolescents perceive and experience their foodscape. Appetite 2023, 190, 107034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laska, M.N.; Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. Does involvement in food preparation track from adolescence to young adulthood and is it associated with better dietary quality? Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, B.; Yazbeck, M. Peer effects, fast food consumption and adolescent weight gain. J. Health Econ. 2015, 42, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stok, F.M.; Renner, B.; Allan, J.; Boeing, H.; Ensenauer, R.; Issanchou, S.; Kiesswetter, E.; Lien, N.; Mazzocchi, M.; Monsivais, P.; et al. Dietary Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Analysis and Taxonomy. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1689. [Google Scholar]

- Hubert, A. Qualitative research in anthropology of food: A comprehensive qualitative-quantitative approach. In Researching Food Habits: Methods and Problems; Macbeth, H., MacClancy, J., Eds.; Berghahn: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

| Research Method | Objective |

|---|---|

| Direct observations | Explore and deepen the understanding of the cultural and social dynamics shaping eating behaviors within the university environment, with midday observations of how students interact among themselves and with food in the university setting to record their behaviors. |

| Field notes | Provide reflections on the research journey and establish a transparent record of the researcher’s experiences, enhancing the study’s scientific rigor. |

| Digital photographs | Enrich field notes by integrating visual depictions that illustrate the food environment and its characteristics. |

| Informal conversations | Serve as an initial method for gathering contextual insights into dietary habits and nutritional quality, engaging diverse stakeholders such as students, faculty, cafeteria staff, and institutional directors. |

| Semi-structured interviews | Act as a primary data source to identify barriers and facilitators for healthy eating. |

| Variable | Category | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 72% |

| Male | 26% | |

| Non-binary | 1% | |

| Socioeconomic status | Less than USD 243/month | 54% |

| USD 243 to USD 490/month | 31% | |

| USD 490 to USD 972/month | 9% | |

| USD 972 to USD 1458/month | 3% | |

| More than USD 1458/month | 2% | |

| Living situation | Alone | 18% |

| Shared apartment with roommates | 8% | |

| With family | 35% | |

| With friends or peers | 38% |

| 0–2 Days/Week | 3–4 Days/Week | 5–6 Days/Week | Daily | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | Fruits | Vegetables | Fruits | Vegetables | Fruits | Vegetables | Fruits | |

| With friends | 42% | 29% | 41% | 39% | 10% | 30% | 8% | 12% |

| With my family | 30% | 23% | 42% | 45% | 18% | 17% | 11% | 15% |

| In a shared apartment | 50% | 21% | 25% | 44% | 13% | 22% | 13% | 13% |

| Alone | 58% | 41% | 31% | 45% | 7% | 9% | 4% | 4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jurado-Gonzalez, P.; López-Toledo, S.; Bach-Faig, A.; Medina, F.-X. Barriers and Enablers of Healthy Eating Among University Students in Oaxaca de Juarez: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071263

Jurado-Gonzalez P, López-Toledo S, Bach-Faig A, Medina F-X. Barriers and Enablers of Healthy Eating Among University Students in Oaxaca de Juarez: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(7):1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071263

Chicago/Turabian StyleJurado-Gonzalez, Patricia, Sabina López-Toledo, Anna Bach-Faig, and Francesc-Xavier Medina. 2025. "Barriers and Enablers of Healthy Eating Among University Students in Oaxaca de Juarez: A Mixed-Methods Study" Nutrients 17, no. 7: 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071263

APA StyleJurado-Gonzalez, P., López-Toledo, S., Bach-Faig, A., & Medina, F.-X. (2025). Barriers and Enablers of Healthy Eating Among University Students in Oaxaca de Juarez: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients, 17(7), 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071263