From Screen to Plate: How Instagram Cooking Videos Promote Healthy Eating Behaviours in Established Adulthood

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Objectives and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Recruitment Methods

2.4. Study Procedure

2.5. Measurement Tools and Data Analysis

2.5.1. Measurement Tools

2.5.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire and Demographic Variables Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Analysis of Each Construct

3.2.1. Cooking Behaviour

3.2.2. Healthy Cooking Techniques Multimedia

3.2.3. Healthy Eating Behaviours

3.2.4. Pearson Correlation Analysis

3.2.5. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Model Fit Testing

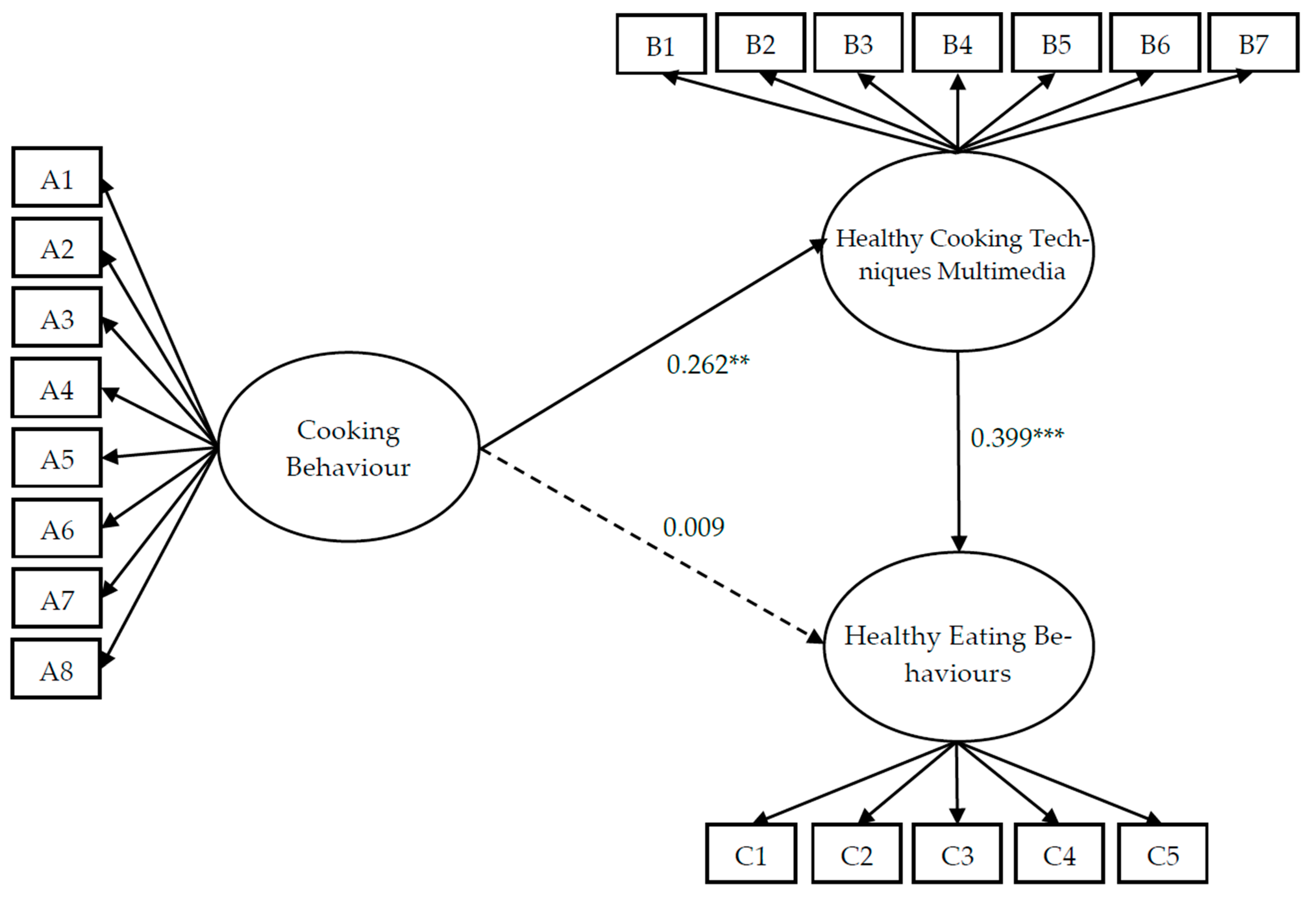

3.3. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Research Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension | Item Description | Mean | Standard Deviation | 95% CI for the Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Cooking Behaviour | I frequently prepare my own meals rather than eating out. | 4.54 | 1.706 | 4.30 | 4.52 |

| I am capable of following recipes or instructional videos to prepare new dishes. | 4.71 | 1.747 | |||

| I have the ability to use various cooking techniques (such as pan-frying, stir-frying, baking, and stewing). | 4.28 | 1.764 | |||

| I regularly plan my weekly meals and prepare ingredients in advance. | 4.48 | 1.769 | |||

| I consider myself proficient in cooking a variety of basic dishes. | 4.44 | 1.798 | |||

| I am confident in accurately measuring ingredient portions and determining appropriate cooking times. | 4.64 | 1.747 | |||

| I enjoy cooking because it provides me with relaxation and a sense of enjoyment. | 4.57 | 1.714 | |||

| My primary motivation for cooking is to maintain a healthy diet. | 3.60 | 1.792 | |||

| Overall Mean | 4.41 | 1.755 | |||

| Healthy Cooking Techniques Multimedia | I frequently watch multimedia content about healthy cooking techniques (e.g., Instagram). | 5.47 | 1.266 | 5.32 | 5.48 |

| I watch videos or programs related to healthy cooking at least once a week. | 5.29 | 1.282 | |||

| Compared to general cooking programs, I prefer watching videos that feature healthy cooking techniques. | 5.39 | 1.291 | |||

| After watching healthy cooking videos, I try to apply the techniques I have learned in my own cooking. | 5.46 | 1.277 | |||

| Watching these videos has increased my confidence in preparing healthy meals. | 5.26 | 1.366 | |||

| I adjust my dietary choices based on the recommendations provided in these videos. | 5.34 | 1.358 | |||

| Through these videos, I have learned healthier cooking methods (such as reducing fat usage and incorporating more natural ingredients). | 5.51 | 1.371 | |||

| Overall Mean | 5.39 | 1.316 | |||

| Healthy Eating Behaviours | I believe that the knowledge acquired from watching healthy cooking videos will influence my dietary habits for at least one year or longer. | 4.72 | 1.397 | 4.93 | 5.09 |

| After watching healthy cooking videos, I consciously reduce the use of high-fat, high-salt, and high-sugar cooking methods. | 4.81 | 1.356 | |||

| After watching healthy cooking videos, I make an effort to use healthier ingredients, such as substituting butter with olive oil. | 5.41 | 1.333 | |||

| After watching healthy cooking videos, I pay attention to nutrition labels when purchasing ingredients to select healthier products. | 5.24 | 1.383 | |||

| I modify my cooking methods based on recommendations from healthy cooking videos to make meals healthier. | 5.21 | 1.394 | |||

| Overall Mean | 5.08 | 1.373 | |||

References

- Chung, A.; Vieira, D.; Donley, T.; Tan, N.; Jean-Louis, G.; Gouley, K.K.; Seixas, A. Adolescent peer influence on eating behaviors via social media: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e19697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramston, V.; Rouf, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The development of cooking videos to encourage calcium intake in young adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surgenor, D.; Hollywood, L.; Furey, S.; Lavelle, F.; McGowan, L.; Spence, M.; Raats, M.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Caraher, M.; et al. The impact of video technology on learning: A cooking skills experiment. Appetite 2017, 114, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ngqangashe, Y.; De Backer, C.J. The differential effects of viewing short-form online culinary videos of fruits and vegetables versus sweet snacks on adolescents’ appetites. Appetite 2021, 166, 105436. [Google Scholar]

- Razali, M.A.; Tazijan, F.N.; Rahim, S.A.; Zulkifli, F.A.; Isa, N.F.; Hemdi, M.A. Perfecting the Culinary Arts via the YouTube way. Int. J. e-Educ. e-Bus. e-Manag. e-Learn. 2012, 2, 214–217. [Google Scholar]

- Surgenor, D.; McMahon-Beattie, U.S.; Burns, A.; Hollywood, L.E. Promoting creativity in the kitchen: Digital lessons from the learning environment. J. Creat. Behav. 2016, 50, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Nour, M.; Cheng, Z.G.; Farrow, J.L.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Short videos addressing barriers to cooking with vegetables in young adults: Pilot testing. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 724–730. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wu, C. The relationship between SNS usage and disordered eating behaviors: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 641919. [Google Scholar]

- Tuong, W.; Larsen, E.R.; Armstrong, A.W. Videos to influence: A systematic review of effectiveness of video-based education in modifying health behaviors. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 37, 218–233. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, N.; Jerin, S.I.; Mu, D. Using TikTok to educate, influence, or inspire? A content analysis of health-related EduTok videos. J. Health Commun. 2023, 28, 539–551. [Google Scholar]

- Ozilgen, S.; Yalcin, S.; Aktuna, M.; Baylan, Y.; Ates, H. From kitchen to climate: Multimedia interventions on social media as science tools for sustainability communication among food business actors. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Surgenor, D.; McLaughlin, C.; McMahon-Beattie, U.; Burns, A. The use of video to maximise cooking skills. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 3918–3937. [Google Scholar]

- Dopelt, K.; Houminer-Klepar, N. The impact of social media on disordered eating: Insights from Israel. Nutrients 2025, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidani, J.E.; Shensa, A.; Hoffman, B.; Hanmer, J.; Primack, B.A. The association between social media use and eating concerns among US young adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Croll, J.K.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. Healthy eating: What does it mean to adolescents? J. Nutr. Educ. 2001, 33, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, S.; Khong, K.W.; Pahlevan Sharif, S.; Ahmed, A. YouTube Video comments on healthy eating: Descriptive and predictive analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19618. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, G.; Corcoran, C.; Tatlow-Golden, M.; Boyland, E.; Rooney, B. See, like, share, remember: Adolescents’ responses to unhealthy-, healthy-and non-food advertising in social media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, A.M.D.; Botelho, A.M.; Dean, M.; Fiates, G.M. Beyond catching a glimpse: Young adults’ perceptions of social media cooking content. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 3624–3643. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, V.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Young Australian adults prefer video posts for dissemination of nutritional information over the social media platform Instagram: A pilot cross-sectional survey. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbardelotto, J.; Martins, B.B.; Buss, C. Use of social networks in the context of the dietitian’s practice in Brazil and changes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploratory study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e31533. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S.H.; Widowati, R.; Cheng, C.J. Investigating Taiwan Instagram users’ behaviors for social media and social commerce development. Entertain. Comput. 2022, 40, 100461. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.I.; Chen, Y.H.; Chu, J.Y. New social media and the displacement effect: University student and staff inter-generational differences in Taiwan. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2042113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, A.M.D.; Botelho, A.M.; Dean, M.; Fiates, G.M.R. Cooking using social media: Young Brazilian adults’ interaction and practices. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1405–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, C.M.; Arnett, J.J.; Palmer, C.G.; Nelson, L.J. Established adulthood: A new conception of ages 30 to 45. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, C.M.; Arnett, J.J. Toward a new theory of established adulthood. J. Adult Dev. 2023, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, A.T.; Tay, L.; Diener, E.; Oishi, S. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Cortes, M.; Andrade Louzado, J.; Galvão Oliveira, M.; Moraes Bezerra, V.; Mistro, S.; Souto Medeiros, D.; Arruda Soares, D.; Oliveira Silva, K.; Nicolaevna Kochergin, C.; Honorato dos Santos de Carvalho, V.C.; et al. Unhealthy Food and Psychological Stress: The Association between Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Perceived Stress in Working-Class Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Conner, M.; Clancy, F.; Moss, R.; Wilding, S.; Bristow, M.; O’Connor, D.B. Stress and eating behaviours in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2022, 16, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klompstra, L.; Löf, M.; Björkelund, C.; Hellenius, M.L.; Kallings, L.V.; Orho-Melander, M.; Wennberg, P.; Bendtsen, P.; Bendtsen, M. Co-occurrence of unhealthy lifestyle behaviours in middle-aged adults: Findings from the Swedish CArdioPulmonary bioImage Study (SCAPIS). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L. Revisiting sample size and number of parameter estimates: Some support for the N: Q hypothesis. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinard, C.A.; Uvena, L.M.; Quam, J.B.; Smith, T.M.; Yaroch, A.L. Development and testing of a revised cooking matters for adults survey. Am. J. Health Behav. 2015, 39, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lahne, J.; Wolfson, J.A.; Trubek, A. Development of the Cooking and Food Provisioning Action Scale (CAFPAS): A new measurement tool for individual cooking practice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 62, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, A.; Ratchford, B.T.; Saint Clair, J.K.; Bui, M.M.; Hamilton, M.L. Dine-in or take-out: Modeling millennials’ cooking motivation and choice. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101981. [Google Scholar]

- Lins, M.F.C.; Botelho, R.B.A.; Romão, B.; Torres, M.L.; Guimarães, N.S.; Zandonadi, R.P. Assessment of Validated Instruments for Measuring Cooking Skills in Adults: A Scoping Review. Foods 2024, 13, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomori, M.M.; Quinaud, R.T.; Condrasky, M.D.; Caraher, M. Brazilian Cooking Skills Questionnaire evaluation of using/cooking and consumption of fruits and vegetables. Nutrition 2022, 95, 111557. [Google Scholar]

- Raber, M.; Baranowski, T.; Crawford, K.; Sharma, S.V.; Schick, V.; Markham, C.; Jia, W.; Sun, M.; Steinman, E.; Chandra, J. The Healthy Cooking Index: Nutrition optimizing home food preparation practices across multiple data collection methods. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Guertin, C.; Pelletier, L.; Pope, P. The validation of the Healthy and Unhealthy Eating Behavior Scale (HUEBS): Examining the interplay between stages of change and motivation and their association with healthy and unhealthy eating behaviors and physical health. Appetite 2020, 144, 104487. [Google Scholar]

- Żakowska-Biemans, S.; Pieniak, Z.; Kostyra, E.; Gutkowska, K. Searching for a measure integrating sustainable and healthy eating behaviors. Nutrients 2019, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, E.; Bilici, S.; Dazıroğlu, M.E.Ç.; Gövez, N.E. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Sustainable and Healthy Eating Behaviors Scale. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 129, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, J.B.; Bentler, P.M. Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Psychology, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J. Current directions in mediation analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wongprawmas, R.; Mora, C.; Pellegrini, N.; Guiné, R.P.; Carini, E.; Sogari, G.; Vittadini, E. Food choice determinants and perceptions of a healthy diet among Italian consumers. Foods 2021, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldavini, J.; Taillie, L.S.; Lytle, L.A.; Berner, M.; Ward, D.S.; Ammerman, A. Cooking matters for kids improves attitudes and self-efficacy related to healthy eating and cooking. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Novotny, D.; Urich, S.M.; Roberts, H.L. Effectiveness of a teaching kitchen intervention on dietary intake, cooking self-efficacy, and psychosocial health. Am. J. Health Educ. 2023, 54, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- French, C.D.; Gomez-Lara, A.; Hee, A.; Shankar, A.; Song, N.; Campos, M.; McCoin, M.; Matias, S.L. Impact of a food skills course with a teaching kitchen on dietary and cooking self-efficacy and behaviors among college students. Nutrients 2024, 16, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczuk, A.J.; Oliver, T.L.; Dowdell, E.B. Social media’s influence on adolescents′ food choices: A mixed studies systematic literature review. Appetite 2022, 168, 105765. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, W. Accurate inference of user popularity preference in a large-scale online video streaming system. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2018, 61, 018101. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhuo, L.; Wang, M. Personalized mobile video recommendation based on user preference modeling by deep features and social tags. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Perez, C.; Vessal, S.R. Using social media for health: How food influencers shape home-cooking intentions through vicarious experience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 204, 123462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Vessal, S.R.; Perez, C. Home cooking in the digital age: When observing food influencers on social media triggers the imitation of their practices. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1152–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matwick, K.; Matwick, K. Reel cooking: How Instagram reimagines recipe narratives. Food Cult. Soc. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Background Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 215 | 44.1 |

| Female | 262 | 53.7 | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 11 | 2.3 | |

| Age | 30–35 years old | 225 | 46.1 |

| 36–40 years old | 146 | 29.9 | |

| 41–45 years old | 117 | 24.0 | |

| Educational background | Elementary school or below | 6 | 1.2 |

| Junior high school (middle school) | 69 | 14.1 | |

| High school or vocational school | 55 | 11.3 | |

| Five-year junior college | 126 | 25.8 | |

| University | 232 | 47.5 | |

| Graduate school or above | 6 | 1.2 | |

| Living situation | Living alone | 51 | 10.5 |

| Living with spouse only (2 people) | 84 | 17.2 | |

| Living with family (more than 2 people) | 341 | 69.9 | |

| Other | 12 | 2.5 |

| Dimension | Cooking Behaviour | Healthy Cooking Techniques Multimedia | Healthy Eating Behaviours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking Behaviour | 1 | ||

| Healthy Cooking Techniques Multimedia | 0.345 ** | 1 | |

| Healthy Eating Behaviours | 0.347 ** | 0.551 ** | 1 |

| Dimension | Item Description | Mean | Standardised Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking Behaviour | I frequently prepare my own meals rather than eating out. | 4.54 | 0.893 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.732 | |||

| I am capable of following recipes or instructional videos to prepare new dishes. | 4.71 | 0.905 | |||||||

| I have the ability to use various cooking techniques (such as pan-frying, stir-frying, baking, and stewing). | 4.28 | 0.913 | |||||||

| I regularly plan my weekly meals and prepare ingredients in advance. | 4.48 | 0.941 | |||||||

| I consider myself proficient in cooking a variety of basic dishes. | 4.44 | 0.871 | |||||||

| I am confident in accurately measuring ingredient portions and determining appropriate cooking times. | 4.64 | 0.803 | |||||||

| I enjoy cooking because it provides me with relaxation and a sense of enjoyment. | 4.57 | 0.73 | |||||||

| My primary motivation for cooking is to maintain a healthy diet. | 3.60 | 0.762 | |||||||

| Healthy Cooking Techniques Multimedia | I frequently watch multimedia content about healthy cooking techniques (e.g., Instagram). | 5.47 | 0.788 | 0.932 | 0.933 | 0.667 | |||

| I watch videos or programs related to healthy cooking at least once a week. | 5.29 | 0.832 | |||||||

| Compared to general cooking programs, I prefer watching videos that feature healthy cooking techniques. | 5.39 | 0.894 | |||||||

| After watching healthy cooking videos, I try to apply the techniques I have learned in my own cooking. | 5.46 | 0.866 | |||||||

| Watching these videos has increased my confidence in preparing healthy meals. | 5.26 | 0.858 | |||||||

| I adjust my dietary choices based on the recommendations provided in these videos. | 5.34 | 0.702 | |||||||

| Through these videos, I have learned healthier cooking methods (such as reducing fat usage and incorporating more natural ingredients). | 5.51 | 0.759 | |||||||

| Healthy Eating Behaviours | I believe that the knowledge acquired from watching healthy cooking videos will influence my dietary habits for at least one year or longer. | 4.72 | 0.724 | 0.917 | 0.917 | 0.691 | |||

| After watching healthy cooking videos, I consciously reduce the use of high-fat, high-salt, and high-sugar cooking methods. | 4.81 | 0.699 | |||||||

| After watching healthy cooking videos, I make an effort to use healthier ingredients, such as substituting butter with olive oil. | 5.41 | 0.897 | |||||||

| After watching healthy cooking videos, I pay attention to nutrition labels when purchasing ingredients to select healthier products. | 5.24 | 0.94 | |||||||

| I modify my cooking methods based on recommendations from healthy cooking videos to make meals healthier. | 5.21 | 0.867 | |||||||

| CFA results | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | NFI | NNFI | GFI | AGFI |

| 1365.236 | 334 | 0.912 | 0.064 | 0.058 | 0.887 | 0.900 | 0.844 | 0.804 | |

| Parameter | Estimate | Bootstrapping | Hypothesis | Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias-Corrected 95% CI | Percentile 95% CI | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Indirect Effect | |||||||

| Cooking Behaviour -> Healthy Cooking Techniques Multimedia -> Healthy Eating Behaviours | 0.105 * | 0.044 | 0.204 | 0.038 | 0.185 | H4 | Supported |

| Direct Effect | |||||||

| Cooking Behaviour -> Healthy Cooking Techniques Multimedia | 0.262 ** | 0.097 | 0.470 | 0.094 | 0.465 | H1 | Supported |

| Cooking Behaviour -> Healthy Eating Behaviours | 0.009 | −0.158 | 0.158 | −0.140 | 0.166 | H2 | Not Supported |

| Healthy Cooking Techniques Multimedia -> Healthy Eating Behaviours | 0.399 *** | 0.248 | 0.575 | 0.246 | 0.573 | H3 | Supported |

| Overall Effect | |||||||

| Cooking Behaviour -> Healthy Eating Behaviours | 0.114 | −0.048 | 0.275 | −0.042 | 0.280 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.-C.; Lee, C.-S.; Chiang, M.-C.; Tsui, P.-L. From Screen to Plate: How Instagram Cooking Videos Promote Healthy Eating Behaviours in Established Adulthood. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1133. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071133

Chen Y-C, Lee C-S, Chiang M-C, Tsui P-L. From Screen to Plate: How Instagram Cooking Videos Promote Healthy Eating Behaviours in Established Adulthood. Nutrients. 2025; 17(7):1133. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071133

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yen-Cheng, Ching-Sung Lee, Ming-Chen Chiang, and Pei-Ling Tsui. 2025. "From Screen to Plate: How Instagram Cooking Videos Promote Healthy Eating Behaviours in Established Adulthood" Nutrients 17, no. 7: 1133. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071133

APA StyleChen, Y.-C., Lee, C.-S., Chiang, M.-C., & Tsui, P.-L. (2025). From Screen to Plate: How Instagram Cooking Videos Promote Healthy Eating Behaviours in Established Adulthood. Nutrients, 17(7), 1133. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071133