Lower Adherence to Lifestyle Recommendations of the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (2018) Is Associated with Decreased Overall 10-Year Survival in Women with Breast Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Baseline

2.1.1. Data on Sociodemographic, Anthropometric, Clinical, and Dietary Aspects

2.1.2. WCRF/AICR Score

2.2. Outcomes

Data on Mortality, Survival, and Recurrence

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Ethical Approval

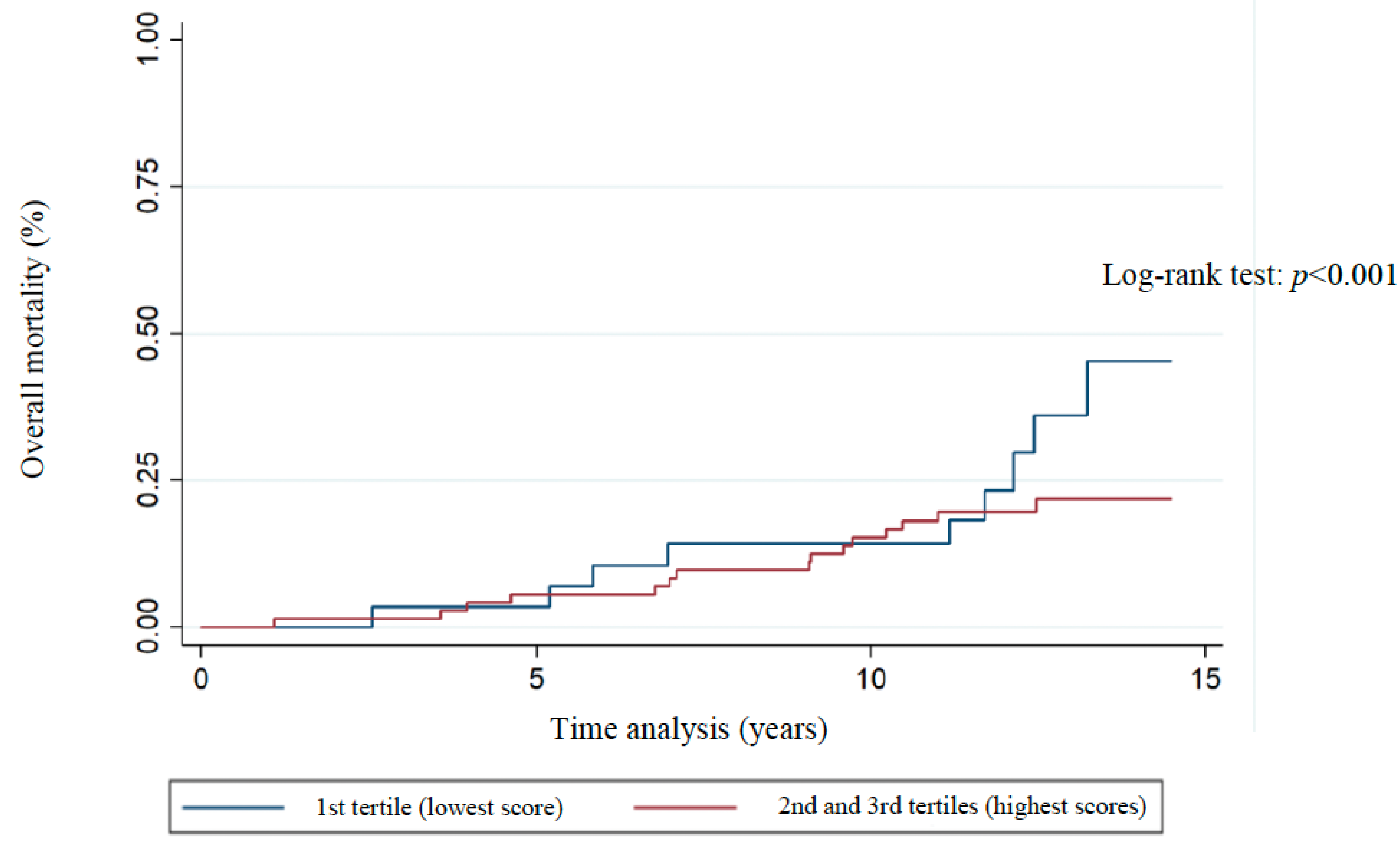

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AICR | American Institute for Cancer Research |

| CI 95% | 95% confidence interval |

| CUP Global | Global Cancer Update Programme |

| FFQ | Food Frequency Questionnaire |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| WCRF | World Cancer Research Fund |

References

- Global Cancer Observatory. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype?sexes=2&single_unit=500000&cancers=20&years=2025 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Estatísticas de Câncer. Available online: https://www.gov.br/inca/pt-br/assuntos/cancer/numeros (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Mariotto, A.B.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, F.; Howlader, N.; Kurian, A.W.; Etzioni, R. Can We Use Survival Data from Cancer Regis-tries to Learn about Disease Recurrence? The Case of Breast Cancer Modeling Recurrence Risk Using Cancer Registry Data. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2018, 27, 1332–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganggayah, M.D.; Taib, N.A.; Har, Y.C.; Lio, P.; Dhillon, S.K. Predicting factors for survival of breast cancer patients using machine learning techniques. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. In Continuous Update Project Expert Report, 3rd ed.; World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 4–112. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Summary-of-Third-Expert-Report-2018.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective, 2nd ed.; Project Expert Report; World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 3–13. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/4841/1/4841.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Body Weight for People Living with and Beyond Breast Cancer. Cancer Update Programme, 1st ed.; World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–50. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/CUP-Global-BCS-Report.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Onyeaghala, G.; Lintelmann, A.K.; Joshu, C.E.; Lutsey, P.L.; Folsom, A.R.; Robien, K.; Platz, E.A.; Prizment, A.E. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research cancer prevention guidelines and colorectal cancer incidence among African Americans and whites: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Cancer 2020, 126, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocío, O.-R.; Macarena, L.-L.; Inmaculada, S.-B.; Antonio, J.-P.; Fernando, V.-A.; Marta, G.-C.; María-José, S.; José-Juan, J.-M. Compliance with the 2018 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Cancer prevention recommendations and prostate cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solans, M.; Romaguera, D.; Gracia-Lavedan, E.; Molinuevo, A.; Benavente, Y.; Saez, M.; Marcos-Gragera, R.; Costas, L.; Robles, C.; Alonso, E.; et al. Adherence to the 2018 WCRF/AICR cancer prevention guidelines and chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the MCC-Spain study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020, 64, 101629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qu-Jin, L.; Fa-Bao, H.; Wu, Y.Q.L.; Liu, S.; Zhong, G.C. Adherence to the 2018 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research cancer prevention recommendations and pancreatic cancer incidence and mortality: A prospective cohort study. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 6843–6853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaguera, D.; Gracia-Lavedan, E.; Molinuevo, A.; de Batlle, J.; Mendez, M.; Moreno, V.; Vidal, C.; Castelló, A.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Martín, V.; et al. Adherence to nutrition-based cancer prevention guidelines and breast, prostate and colorectal cancer risk in the MCC-S pain case–control study. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, R.S.; Wang, T.; Xue, X.; Kamensky, V.; Rohan, T.E. Genetic factors, adherence to healthy lifestyle behavior, and risk of invasive breast cancer among women in the UK Biobank. JNCI: J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turati, F.; Dalmartello, M.; Bravi, F.; Serraino, D.; Augustin, L.; Giacosa, A.; Negri, E.; Levi, F.; La Vecchia, C. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Recommendations and the risk of breast cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Rodríguez, R.; Toledo, E.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Aguilera-Buenosvinos, I.; Romanos-Nanclares, A.; Jiménez-Moleón, J.J. Adherence to the 2018 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Recommendations and Breast Cancer in the SUN Project. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, I.; Taljaard-Krugell, C.; Wicks, M.; Cubasch, H.; Joffe, M.; Laubscher, R.; Romieu, I.; Biessy, C.; Gunter, M.J.; Huybrechts, I.; et al. Adherence to cancer prevention recommendations is associated with a lower breast cancer risk in black urban South African women. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, R.; Van Le, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhang, D.; Gu, H.; Yang, Y.; Sonne, C.; Lam, S.S.; Zhong, J.; Jianguang, Z.; et al. A review of dietary phytochemicals and their relation to oxidative stress and human diseases. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huertas, J.R.; Casuso, R.A.; Agustín, P.H.; Cogliati, S. Stay fit, stay young: Mitochondria in movement: The role of exercise in the new mitochondrial paradigm. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7058350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, T.M.; Kyrou, I.; Randeva, H.S.; Weickert, M.O. Mechanisms of insulin resistance at the crossroad of obesity with associated metabolic abnormalities and cognitive dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.P.; Patil, T.M.; Shinde, A.R.; Vakhariya, R.R.; Mohite, S.K.; Magdum, C.S. Nutrition, Lifestyle & Immunity: Maintaining Optimal Immune Function & Boost Our Immunity. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 2021, 9, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zutphen, M.; Kampman, E.; Giovannucci, E.L.; van Duijnhoven, F.J. Lifestyle after colorectal cancer diagnosis in relation to survival and recurrence: A review of the literature. Curr. Color. Cancer Rep. 2017, 13, 370–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilidis, K.K.; Cariolou, M.; Becerra-Tomás, N.; Balducci, K.; Vieira, R.; Abar, L.; Aune, D.; Markozannes, G.; Nanu, N.; Greenwood, D.C.; et al. Postdiagnosis body fatness, recreational physical activity, dietary factors and breast cancer prognosis: Global Cancer Update Programme (CUP Global) summary of evidence grading. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 152, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue-Choi, M.; Robien, K.; Lazovich, D. Adherence to the WCRF/AICR Guidelines for Cancer Prevention Is Associated with Lower Mortality among Older Female Cancer Survivors The WCRF/AICR Guidelines and Mortality Among Cancer Survivors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2013, 22, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastert, T.A.; Beresford, S.A.; Sheppard, L.; White, E. Adherence to the WCRF/AICR cancer prevention recommendations and cancer-specific mortality: Results from the Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) Study. Cancer Causes Control 2014, 25, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, T.; Faeh, D.; Bopp, M.; Rohrmann, S. Swiss National Cohort Study Group. Adherence to the cancer prevention recom-mendations of the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research and mortality: A census-linked co-hort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenkhuis, M.-F.; Mols, F.; van Roekel, E.H.; Breedveld-Peters, J.J.L.; Breukink, S.O.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.G.; Keulen, E.T.P.; van Duijnhoven, F.J.B.; Weijenberg, M.P.; Bours, M.J.L. Longitudinal Associations of Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) Lifestyle Recommendations with Quality of Life and Symptoms in Colorectal Cancer Survivors up to 24 Months Post-Treatment. Cancers 2022, 14, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, T.T.X.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, M.K.; Chang, Y.J.; Jung, S.-Y.; Cho, H.; Lee, E.S. Prognostic value of post-diagnosis health-related quality of life for overall survival in breast cancer: Findings from a 10-year prospective cohort in Korea. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 51, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, T.M.; Latenstein, A.E.; Sprangers, M.A.; van der Geest, L.G.; Creemers, G.-J.; van Dieren, S.; de Groot, J.-W.B.; Koerkamp, B.G.; de Hingh, I.H.; Homs, M.Y.; et al. Relationship between quality of life and survival in patients with pancre-atic and periampullary cancer: A multicenter cohort analysis. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 1354–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satagopan, J.M.; Dharamdasani, T.; Mathur, S.; Kohler, R.E.; Bandera, E.V.; Kinney, A.Y. Experiences and lessons learned from community-engaged recruitment for the South Asian breast cancer study in New Jersey during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.W.; Wu, M.L.; Tung, H.H. Relationships between health literacy and quality of life among survivors with breast cancer. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2021, 27, e12922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.S.; França, A.C.W.; Padilla, M.P.; Macedo, L.S.; Magliano, C.A.D.S.; Santos, M.D.S. Brazilian breast cancer patient-reported outcomes: What really matters for these women. Front. Med. Technol. 2022, 4, 809222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Union Against Cancer. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. Union for International Cancer Control. 1988. Available online: www.uicc.org/resources/tnm?gclid=Cj0KCQiAvJXxBRCeARIsAMSkApqIe3qFpoCeVAjryKBLZTIRzlLSZWvF0Ca3bdhAYfzhxZu-odWhrAAaAtkEEALw_wcB (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Di Pietro, P.F.; Medeiros, N.I.; Vieira, F.G.K.; Fausto, M.A.; Belló-Klein, A. Breast cancer in southern Brazil: Association with past dietary intake. Nutr Hosp. 2007, 22, 565–572. [Google Scholar]

- Rockenbach, G.; Di Pietro, P.F.; Ambrosi, C.; Boaventura, B.C.B.; Vieira, F.G.K.; Crippa, C.G.; Da Silva, E.L.; Fausto, M.A. Dietary intake and oxidative stress in breast cancer: Before and after treatments. Nutr. Hosp. 2011, 26, 737–744. [Google Scholar]

- Frisancho, A.R. New standards of weight and body composition by frame size and height for assessment of nutritional status of adults and the elderly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984, 40, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO expert committee. World Health Organ Technol. Rep. Ser. 1995, 854, 312–409. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic; WHO Technical Report Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- US Physical Activity Guidelines. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sichieri, R.; Everhart, J.E. Validity of a Brazilian food frequency questionnaire against dietary recalls and estimated energy intake. Nutr. Res. 1998, 18, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, N. Food Intake and Plasma Antioxidant Levels in Women with Breast Cancer. Master Thesis, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, Brazil, 2004. Available online: https://repositorio.ufsc.br/bitstream/handle/123456789/87187/203611.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Pinheiro, A.B.V.; Lacerda, E.M.D.A.; Benzecry, E.H.; Gomes, M.C.S.; Costa, V.M. Table for Evaluating Food Consumption in Household Measures; Atheneu: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2008; pp. 1–131. [Google Scholar]

- Nucleus of Studies and Research in Food. Brazilian Food Composition Table–UNICAMP, 4th ed.; NEPA-UNICAMP: Campinas, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture–USDA. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 18. Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA: Economic Research Service. 2005. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl (accessed on 6 May 2011).

- Willett, W.C.; Howe, G.R.; Kushi, L.H. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 1220S–1228S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Agriculture and Supply of the State of São Paulo (Brazil). Food Crop Table. Available online: www.agricultura.sp.gov.br/ (accessed on 12 February 2010).

- Shams-White, M.M.; Brockton, N.T.; Mitrou, P.; Romaguera, D.; Brown, S.; Bender, A.; Kahle, L.L.; Reedy, J. Operationalizing the 2018 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) cancer prevention recommendations: A standardized scoring system. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannioto, R.A.; Attwood, K.M.; Davis, E.W.; Mendicino, L.A.; Hutson, A.; Zirpoli, G.R.; Tang, L.; Nair, N.M.; Barlow, W.; Hershman, D.L.; et al. Adherence to cancer prevention lifestyle recommendations before, during, and 2 years after treatment for high-risk breast cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2311673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.; Moubarac, J.C.; Jaime, P.; Martins, A.P.; Canella, D.; Louzada, M.; Parra, D.; Ricardo, C.; et al. NOVA. The star shines bright. World Nutr. J. 2016, 7, 8–38. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute On Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. What is a Standard Drink? Available online: www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/what-standard-drink#:~:text=In%20the%20United%20States%2C%20one,which%20is%20about%2040%25%20alcohol (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Malcomson, F.C.; Parra-Soto, S.; Ho, F.K.; Celis-Morales, C.; Sharp, L.; Mathers, J.C. Abbreviated score to assess adherence to the 2018 WCRF/AICR Cancer Prevention Recommendations and risk of cancer in the UK Biobank. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2024, 33, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992; Volume 3, pp. 1–807. [Google Scholar]

- Heitz, A.E.; Baumgartner, R.N.; Baumgartner, K.B.; Boone, S.D. Healthy lifestyle impact on breast cancer-specific and all-cause mortality. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 167, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. What is Cancer Recurrence? Available online: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/survivorship-during-and-after-treatment/understanding-recurrence/what-is-cancer-recurrence.html#:~:text=If%20cancer%20is%20found%20after,somewhere%20else%20in%20the%20body (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Breast Cancer Organization. Recurrent Breast Cancer. 2020. Available online: https://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/diagnosis/recurrent (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Ministry Of Health (Brazil). Resolution Number 466/2012. National Health Council. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2013/res0466_12_12_2012.html (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Shams-White, M.M.; Brockton, N.T.; Mitrou, P.; Kahle, L.L.; Reedy, J. The 2018 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) Score and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality risk: A longitudinal analysis in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhu, Y.; Qian, Q.; Tang, L. Body mass index and prognosis of breast cancer: An analysis by menstruation status when breast cancer diagnosis. Medicine 2018, 97, e11220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spei, M.E.; Samoli, E.; Bravi, F.; La Vecchia, C.; Bamia, C.; Benetou, V. Physical activity in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis on overall and breast cancer survival. Breast 2019, 44, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cai, H.; Gu, K.; Shi, L.; Yu, D.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, Y.; Bao, P.-P.; Shu, X.-O. Adherence to dietary recommendations among long-term breast cancer survivors and cancer outcome associations. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liang, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Ding, X.; Zhang, R.; Mao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Kan, Q.; Sun, T. Association between intake of sweetened beverages with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Public Health 2022, 44, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cicco, P.; Catani, M.V.; Gasperi, V.; Sibilano, M.; Quaglietta, M.; Savini, I. Nutrition and breast cancer: A literature review on prevention, treatment and recurrence. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maso, M.; Maso, L.D.; Augustin, L.S.A.; Puppo, A.; Falcini, F.; Stocco, C.; Mattioli, V.; Serraino, D.; Polesel, J. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and mortality after breast cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cao, D.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B.; Li, J.; Guo, J.; Dong, Q.; Liu, L.; Wei, Q. Red and processed meat consumption and cancer outcomes: Umbrella review. Food Chem. 2021, 356, 129697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinomar, N.; Thai, A.; Cloud, A.J.; McDonald, J.A.; Liao, Y.; Terry, M.B. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer-specific and all-cause mortality in women diagnosed with breast cancer at the New York site of the Breast Cancer Family Registry. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, T.; Yamagishi, K.; Yatsuya, H.; Tanabe, N.; Tamakoshi, A.; Iso, H. Alcohol consumption and mortality from aortic disease among Japanese men: The Japan collaborative cohort study. Atherosclerosis 2017, 266, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Östergren, O.; Martikainen, P.; Tarkiainen, L.; Elstad, J.I.; Brønnum-Hansen, H. Contribution of smoking and alcohol consumption to income differences in life expectancy: Evidence using Danish, Finnish, Norwegian and Swedish register data. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochems, S.H.; Van Osch, F.H.; Bryan, R.T.; Wesselius, A.; van Schooten, F.J.; Cheng, K.K.; Zeegers, M.P. Impact of dietary patterns and the main food groups on mortality and recurrence in cancer survivors: A systematic review of current epidemiological literature. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e014530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaledkiewicz, E.; Szostak-Wegierek, D. Dietary practices and nutritional status in survivors of breast cancer. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2018, 69, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, J.Y.; Sharma, D.; Jerome, G.; Augusto Santa-Maria, C. Obese breast cancer patients and survivors: Management considerations. Oncology 2018, 32, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berrino, F. Life style prevention of cancer recurrence: The yin and the yang. Adv. Nutr. Cancer 2014, 2014, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortazar, P.; Zhang, L.; Untch, M.; Mehta, K.; Costantino, J.P.; Wolmark, N.; Bonnefoi, H.; Cameron, D.; Gianni, L.; Valagussa, P.; et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 2014, 384, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spring, L.M.; Fell, G.; Arfe, A.; Sharma, C.; Greenup, R.; Reynolds, K.L.; Smith, B.L.; Alexander, B.; Moy, B.; Isakoff, S.J.; et al. Pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and impact on breast cancer recurrence and survival: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2838–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WCRF/AICR Recommendations 1 | Operationalization 2 | Points 2 | Operational Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | BMI and waist circumference were classified. | ||

| 1. Have a healthy body weight | 18.5–24.9 | 0.5 | |

| 25–29.9 | 0.25 | ||

| <18.5 or 30 | 0 | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | |||

| <80 | 0.5 | ||

| 80–<88 | 0.25 | ||

| ≥88 | 0 | ||

| 2. Be physically active | Moderate-vigorous total physical activity (min/week) | According to the duration (min/week). Moderate-intensity exercise: walking, housework, cycling, dancing, and gardening. Vigorous exercise: encompasses fast swimming and cycling, running, aerobic activities | |

| ≥150 | 1 | ||

| 75–<150 | 0.5 | ||

| <75 | 0 | ||

| 3. Eat a diet rich in whole grains, vegetables, fruits and legumes | Fruits and vegetables (g/d) | Analysis of consumption (g/day) of fruits and vegetables and fiber intake. All foods consumed that provide fiber to the diet were considered for fiber intake 2 | |

| ≥400 | 0.5 | ||

| 200–<400 | 0.25 | ||

| <200 | 0 | ||

| Total fibers (g/d) | |||

| ≥30 | 0.5 | ||

| 15–<30 | 0.25 | ||

| <15 | 0 | ||

| 4. Limit consumption of fast food and other processed foods rich in fat, starch, and sugar | Percentage of total kcal of ultra-processed foods | Total energy intake was analyzed in tertiles, and the total energy value of ultra-processed foods consumed was allocated to the specific tertile. Food items characterized as ultra-processed followed the NOVA classification 3 | |

| 5. Limit the consumption of red and processed meat | Total red meat (g/week) andprocessed meat (g/week) | The food items analyzed in this category also followed the NOVA classification 3, with beef, pork, and liver being red meat and processed meat attributed to sausage, ham, hamburger, ground beef, and bacon. Such food items were analyzed according to weekly consumption (g/week) 2 | |

| Red meat < 500 and processed meat < 21 | 1 | ||

| Red meat < 500 and processed meat 21–<100 | 0.5 | ||

| Red meat > 500 or processed meat ≥ 100 | 0 | ||

| 6. Limit the consumption of sugary drinks | Total sugary drinks (g/d) | Analysis of the daily consumption of industrialized/artificial juices and soft drinks, refined sugar, and honey 3 | |

| 0 | 1 | ||

| >0–≤250 | 0.5 | ||

| >250 | 0 | ||

| 7. Limit alcohol consumption | Total ethanol (g/d) | A conversion of the volume (mL) of alcohol ingested (from any alcoholic beverages, such as wine, beer, and distilled drinks) was carried out in grams of ethanol according to the specific alcohol content of the drink 4 | |

| 0 | 1 | ||

| ≤14 (1 drink) | 0.5 | ||

| >14 (1 drink) | 0 | ||

| 8. Breastfeeding | - | - | It was excluded from the score applied in this study, given that the data necessary for its operationalization were not available. It is noteworthy that the score used allows the total sum without this component 2 |

| TOTAL SCORE RANGE | 0–7 | ||

| Variable | Groups of Adherence to the WCRF/AICR Recommendations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Tertile * (n = 34) | 2nd and 3rd Tertiles (n = 67) | p | |

| Age (average), SD | 51.1 (1.7) | 51.1 (1.4) | 0.976 a |

| Number of comorbidities, average (SD) | 2.3 (0.4) | 2.4 (0.2) | 0.961 a |

| Ethnic group, n (%) | 0.006 b | ||

| Caucasian | 28 (29.8) | 66 (70.2) | |

| Non-white (or Afro-descendant) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Years of study, mean (SD) | 7.6 (0.7) | 6.8 (0.5) | 0.368 a |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Married/stable union | 21 (31.3) | 46 (68.7) | 0.511 b |

| Not married/no stable union | 13 (38.2) | 21 (61.8) | |

| Continuous use of medications, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 19 (32.2) | 40 (67.8) | 0.831 b |

| No | 15 (35.7) | 27 (64.3) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 5 (27.8) | 13 (72.2) | 0.784 b |

| No | 29 (34.9) | 54 (65.1) | |

| Family history of breast cancer, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 14 (38.9) | 22 (61.1) | 0.510 b |

| No | 20 (30.8) | 45 (69.2) | |

| Variable | Unadjusted Analysis a | Adjusted Analysis b | Adjusted Analysis b,c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (CI 95%) | p | HR (CI 95%) | p | HR (CI 95%) | p | |

| Overall mortality (n = 24 *) | 2.02 (0.71–5.74) | 0.185 | 1.12 (0.47–2.66) | 0.782 | 1.75 (0.54–5.69) | 0.348 |

| Breast cancer-specific mortality (n = 15 *) | 1.19 (0.37–3.81) | 0.254 | 0.89 (0.21–3.73) | 0.875 | 1.53 (0.30–7.81) | 0.606 |

| Overall 10-year survival d (n = 84 *) | 0.16 (0.03–0.8) | 0.025 | 0.16 (0.28–0.96) | 0.045 | 0.17 (0.02–1.2) | 0.076 |

| Recurrence (n = 36 *) | 0.91 (0.43–1.91) | 0.810 | 0.97 (0.45–2.1) | 0.946 | 0.97 (0.45–2.1) | 0.946 |

| 10-year recurrence e (n = 24 *) | 1.32 (0.48–3.63) | 0.580 | 1.43 (0.48–4.23) | 0.510 | 1.43 (0.48–4.23) | 0.510 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Souza, J.S.; Reitz, L.K.; Copetti, C.L.K.; Moreno, Y.M.F.; Vieira, F.G.K.; Di Pietro, P.F. Lower Adherence to Lifestyle Recommendations of the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (2018) Is Associated with Decreased Overall 10-Year Survival in Women with Breast Cancer. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061001

de Souza JS, Reitz LK, Copetti CLK, Moreno YMF, Vieira FGK, Di Pietro PF. Lower Adherence to Lifestyle Recommendations of the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (2018) Is Associated with Decreased Overall 10-Year Survival in Women with Breast Cancer. Nutrients. 2025; 17(6):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061001

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Souza, Jaqueline Schroeder, Luiza Kuhnen Reitz, Cândice Laís Knöner Copetti, Yara Maria Franco Moreno, Francilene Gracieli Kunradi Vieira, and Patricia Faria Di Pietro. 2025. "Lower Adherence to Lifestyle Recommendations of the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (2018) Is Associated with Decreased Overall 10-Year Survival in Women with Breast Cancer" Nutrients 17, no. 6: 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061001

APA Stylede Souza, J. S., Reitz, L. K., Copetti, C. L. K., Moreno, Y. M. F., Vieira, F. G. K., & Di Pietro, P. F. (2025). Lower Adherence to Lifestyle Recommendations of the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (2018) Is Associated with Decreased Overall 10-Year Survival in Women with Breast Cancer. Nutrients, 17(6), 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061001