Validation Evidence for the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) in Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collected

2.3.1. Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ)

2.3.2. Sociodemographic Variables

2.3.3. Children’s Anthropometric Measurements

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Psychometric Properties and Data Analysis

2.5.1. Concurrent Criterion Validity

2.5.2. Construct Validity

2.5.3. Reliability

2.5.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Criterion Validity

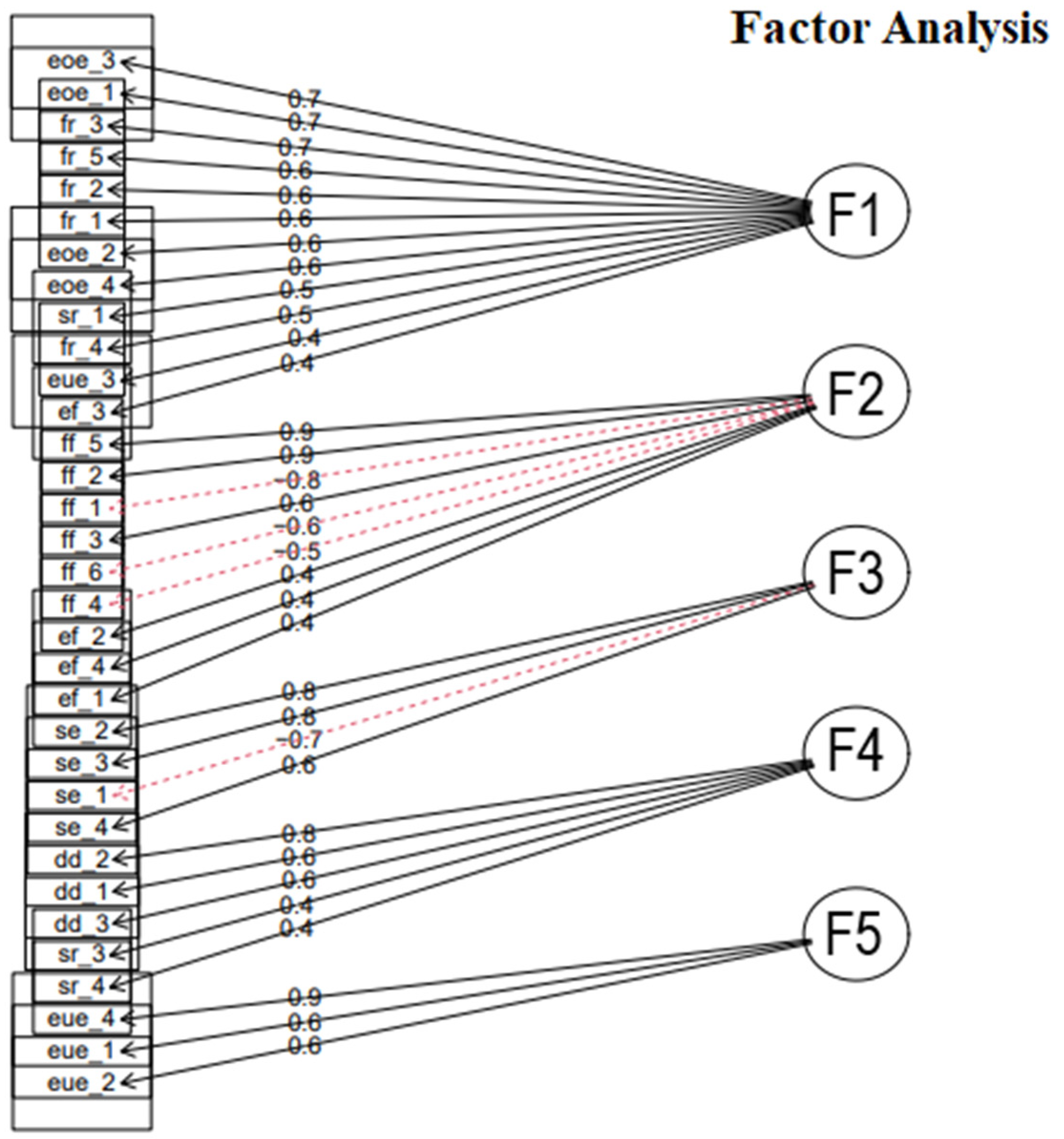

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

3.4. Internal Consistency

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramos, M.; Stein, L.M. Desenvolvimento do comportamento alimentar infantil. J. Pediatr. 2000, 76, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz-Silva, J.; Prado, S.D.; Seixas, C.M. Comportamento alimentar no campo da Alimentação e Nutrição: Do que estamos falando? Physis Rev. Saúde Coletiva 2016, 26, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Moreira, E.A.M.; Rauen, M.S. Determinantes do comportamento alimentar: Uma revisão com enfoque na família. Rev. Nutr. 2008, 21, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Proportion of Disordered Eating in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis|Psychiatry and Behavioral Health|JAMA Pediatrics|JAMA Network. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2801664#note-POI220096-1 (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Associação Brasileira de Nutrição-ASBRAN; Marcia Samia Pinheiro Fidelix. Manual Orientativo: Sistematização Do Cuidado de Nutrição; Associação Brasileira de Nutrição: São Paulo, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, J.; Guthrie, C.A.; Sanderson, S.; Rapoport, L. Development of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamad, A.H.; Al-Naseeb, A.M.; Al-Assaf, M.S.; Al-Obaid, S.A.; Al-Abdulkarim, B.S.; Olszewski, P.K. Preliminary Exploration of Obesity-Related Eating Behaviour Patterns in a Sample of Saudi Preschoolers Aged 2-6 Years through the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczyk, Ż.; Kuczka, O.; Pasztak-Opiłka, A.; Zachurzok, A. Validation of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire in Poland. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleddens, E.F.; Kremers, S.P.; Thijs, C. The Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire: Factorial Validity and Association with Body Mass Index in Dutch Children Aged 6–7. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, N.W.; Gebreyesus, S.H.; Hassen, H.Y.; Habtemariam, E.; Abebe, D.S. Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire in Ethiopia. J. Nutr. Sci. 2021, 10, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, V.; Sinde, S. O Comportamento Alimentar Em Crianças:Estudo de Validação de Um Questionário Numa Amostra Portuguesa (CEBQ). Análise Psicológica 2008, 1, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peuckert, M.Z.; Ayala, C.O.; Mattiello, R.; dos Santos, T.S.; Walker, M.S.; Feoli, A.M.P.; Costa, C.A.D. Tradução e adaptação transcultural do Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) para o Brasil. Sci. Medica 2024, 34, e45338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growth Reference Data for 5–19 Years. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards Based on Length/Height, Weight and Age. Acta Paediatr. Oslo Nor. 1992 Suppl. 2006, 450, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Onis, M.; Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E.; Siyam, A.; Nishida, C.; Siekmann, J. Development of a WHO Growth Reference for School-Aged Children and Adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Prinsen, C.A.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Study Design Checklist for Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Instruments; Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Damásio, B.F. Uso da análise fatorial exploratória em psicologia. Aval. Psicológica 2012, 11, 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, D.A.S.; Rodrigues, E.C. Análise Fatorial; Escola Nacional de Administração Pública (Enap): Brasília, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali, L. Psicometria. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2009, 43, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.C.d.; Alexandre, N.M.C.; Guirardello, E.d.B. Propriedades psicométricas na avaliação de instrumentos: Avaliação da confiabilidade e da validade. Epidemiol. E Serviços Saúde 2017, 26, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Factor Analysis as a Tool for Survey Analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, V.; Lundborg, L.; Cao, Y.; Nowicka, P.; Marcus, C.; Sobko, T. Obesity Related Eating Behaviour Patterns in Swedish Preschool Children and Association with Age, Gender, Relative Weight and Parental Weight—Factorial Validation of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quah, P.L.; Fries, L.R.; Chan, M.J.; Fogel, A.; McCrickerd, K.; Goh, A.T.; Aris, I.M.; Lee, Y.S.; Pang, W.W.; Basnyat, I.; et al. Validation of the Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire in 5 and 6 Year-Old Children: The GUSTO Cohort Study. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, M.A.; Strong, D.R.; Sim, D.E.K.; Rhee, K.E.; Boutelle, K.N. Psychometric properties of the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ) in school-age children with overweight and obesity: A proposed three-factor structure. Pediatr. Obes. 2021, 16, e12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, V.; Sinde, S.; Saxton, J.C. Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire: Associations with BMI in Portuguese children. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.L.; Ho-Urriola, J.A.; González, A.; Smalley, S.V.; Domínguez-Vásquez, P.; Cataldo, R.; Obregón, A.M.; Amador, P.; Weisstaub, G.; Hodgson, M.I. Association between Eating Behavior Scores and Obesity in Chilean Children. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, U.; Singh, S. Role of Somatostatin in the Regulation of Central and Peripheral Factors of Satiety and Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta 08|Escolaridade Média. Available online: https://www.observatoriodopne.org.br/ (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Tabela 5436: Rendimento Médio Mensal Real das Pessoas de 14 Anos ou Mais de Idade Ocupadas na Semana de Referência Com Rendimento de Trabalho, Habitualmente e Efetivamente Recebidos no Trabalho Principal e em Todos os Trabalhos, Por Sexo. Available online: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/tabela/5436#resultado (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Leuba, A.L.; Meyer, A.H.; Kakebeeke, T.H.; Stülb, K.; Arhab, A.; Zysset, A.E.; Leeger-Aschmann, C.S.; Schmutz, E.A.; Kriemler, S.; Jenni, O.G.; et al. Eating behaviour in Swiss preschool children–Validation of a German and a French version of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.-T.; Svensson, V.; Marcus, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.-D.; Sobko, T. Eating Behaviour Patterns in Chinese Children Aged 12-18 Months and Association with Relative Weight—Factorial Validation of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Level of education | |

| No schooling completed | 2 (0.98) |

| Incomplete elementary school | 25 (12.20) |

| Complete elementary school | 8 (3.90) |

| Incomplete high school | 21 (10.25) |

| Complete high school | 12 (5.85) |

| Incomplete technical degree | 1 (0.50) |

| Complete technical degree | 6 (2.92) |

| Incomplete college degree | 7 (3.41) |

| Complete college degree | 44 (21.46) |

| Graduate degree (beyond bachelor’s degree) | 79 (38.53) |

| Monthly family income (R$) | |

| Up to 300.00 | 7 (3.41) |

| 301.00–500.00 | 6 (2.93) |

| 501.00–800.00 | 17 (8.29) |

| 801.00–1212.00 | 24 (11.70) |

| 1213.00–2424.00 | 16 (7.80) |

| 2425.00–3636.00 | 8 (3.90) |

| 3637.00–4848.00 | 2 (0.99) |

| 4849.00–6060.00 | 17 (8.30) |

| >6061.00 | 108 (52.68) |

| Kinship | |

| Mother | 159 (77.56) |

| Father | 33 (16.09) |

| Grandmother | 6 (2.92) |

| Grandfather | 3 (1.47) |

| Uncle/aunt | 4 (1.96) |

| Race/skin color | |

| White | 138 (67.31) |

| Black | 43 (20.97) |

| Yellow (Asian descent) | 2 (0.98) |

| Indigenous | 1 (0.49) |

| Brown (mixed race) | 21 (10.25) |

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 7.72 (2.38) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 97 (47.32) |

| Male | 108 (52.68) |

| Skin color, n (%) | |

| White | 147 (71.71) |

| Black | 33 (16.10) |

| Yellow (Asian descent) | 2 (0.97) |

| Indigenous | 0 (0.0) |

| Brown (mixed race) | 23 (11.22) |

| Nutritional status (z-score), n (%) | |

| Severe thinness | 1 (0.49) |

| Thinness | 2 (0.98) |

| Normal weight | 96 (46.83) |

| Risk of overweight | 16 (7.80) |

| Overweight | 54 (26.34) |

| Obesity | 24 (11.71) |

| Severe obesity | 12 (5.85) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 30.12 (10.93) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 126.03 (17.61) |

| BMI-for-age, mean (SD) | 1.02 (1.35) |

| Height-for-age, mean (SD) | 0.21 (1.11) |

| Scale | rho | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Satiety responsiveness | −0.2631 | 0.0001 * |

| Slowness in eating | −0.1534 | 0.0279 * |

| Enjoyment of food | 0.1677 | 0.0162 * |

| Food fussiness | −0.0339 | 0.6289 |

| Emotional undereating | −0.0774 | 0.2695 |

| Desire to drink | 0.0160 | 0.8189 |

| Emotional overeating | 0.1619 | 0.0203 * |

| Food responsiveness | 0.1735 | 0.0128 * |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My child eats more when anxious. | 0.75 | ||||

| My child eats more when worried. | 0.67 | ||||

| Given the choice, my child would eat most of the time. | 0.67 | ||||

| If given the chance, my child would always have food in his/her mouth. | 0.64 | ||||

| If allowed to, my child would eat too much. | 0.63 | ||||

| My child is always asking for food. | 0.59 | ||||

| My child eats more when annoyed. | 0.59 | ||||

| My child eats more when s/he has nothing else to do. | 0.57 | ||||

| My child has a big appetite. | 0.51 | ||||

| Even if my child is full up, she/he finds room to eat his/her favorite food. | 0.48 | ||||

| My child eats more when s/he is happy. | 0.43 | ||||

| My child looks forward to mealtimes. | 0.41 | ||||

| My child is interested in tasting food she/he hasn’t tasted before. | 0.88 | ||||

| My child enjoys tasting new foods. | 0.87 | ||||

| My child refuses new foods at first. | −0.75 | ||||

| My child enjoys a wide variety of foods. | 0.65 | ||||

| My child decides that s/he doesn’t like a food, even without tasting it. | −0.61 | ||||

| My child is difficult to please with meals. | −0.53 | ||||

| My child is interested in food. | 0.43 | ||||

| My child enjoys eating. | 0.42 | ||||

| My child loves food. | 0.37 | ||||

| My child eats slowly. | 0.77 | ||||

| My child takes more than 30 min to finish a meal. | 0.75 | ||||

| My child finishes his/her meal quickly. | 0.71 | ||||

| My child eats more and more slowly during a meal. | 0.57 | ||||

| If given the chance, my child would drink continuously throughout the day. | 0.78 | ||||

| My child is always asking for a drink. | 0.64 | ||||

| If given the chance, my child would always be having a drink. | 0.56 | ||||

| My child eats less when upset. | 0.86 | ||||

| My child eats less when angry. | 0.58 | ||||

| My child eats less when she/he is tired. | 0.55 |

| Factor | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|

| Overeating | 0.82 |

| Enjoyment of food | 0.88 |

| Slowness in eating | 0.78 |

| Desire to drink | 0.78 |

| Emotional undereating | 0.70 |

| Total | 0.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peuckert, M.Z.; Ayala, C.O.; Mattiello, R.; Viola, T.W.; Walker, M.S.; Feoli, A.M.P.; Drumond Costa, C.A. Validation Evidence for the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) in Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050851

Peuckert MZ, Ayala CO, Mattiello R, Viola TW, Walker MS, Feoli AMP, Drumond Costa CA. Validation Evidence for the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) in Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(5):851. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050851

Chicago/Turabian StylePeuckert, Marina Zanette, Camila Ospina Ayala, Rita Mattiello, Thiago Wendt Viola, Marthina Streda Walker, Ana Maria Pandolfo Feoli, and Caroline Abud Drumond Costa. 2025. "Validation Evidence for the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) in Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study" Nutrients 17, no. 5: 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050851

APA StylePeuckert, M. Z., Ayala, C. O., Mattiello, R., Viola, T. W., Walker, M. S., Feoli, A. M. P., & Drumond Costa, C. A. (2025). Validation Evidence for the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) in Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 17(5), 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050851