Guideline Compliance of Artificial Intelligence–Generated Diet Plans After Bariatric Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Simulation Comparing ChatGPT-4o, DeepSeek and Grok-3

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients Simulation

2.2. Prompts Entered into AI Models

“Can you prepare a nutrition plan for a 24-year-old male who is 169 cm tall, weighs 115 kg, is sedentary, and is on day 35 post-sleeve gastrectomy?”

“Can you prepare a nutrition plan for a 21-year-old female who is 170 cm tall, weighs 120 kg, is sedentary, and is on day 16 post-sleeve gastrectomy?”

2.3. Diet Plan Evaluation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

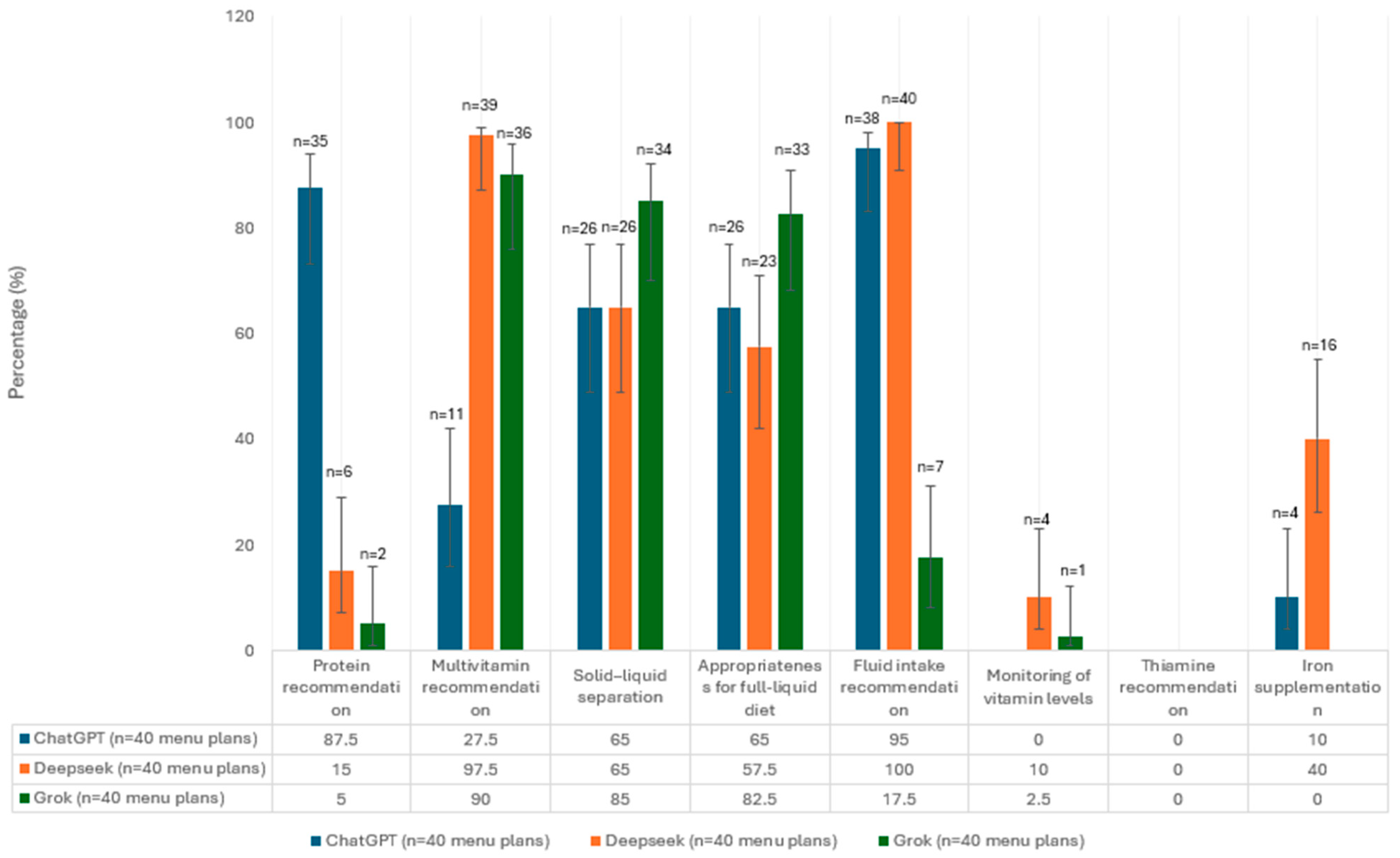

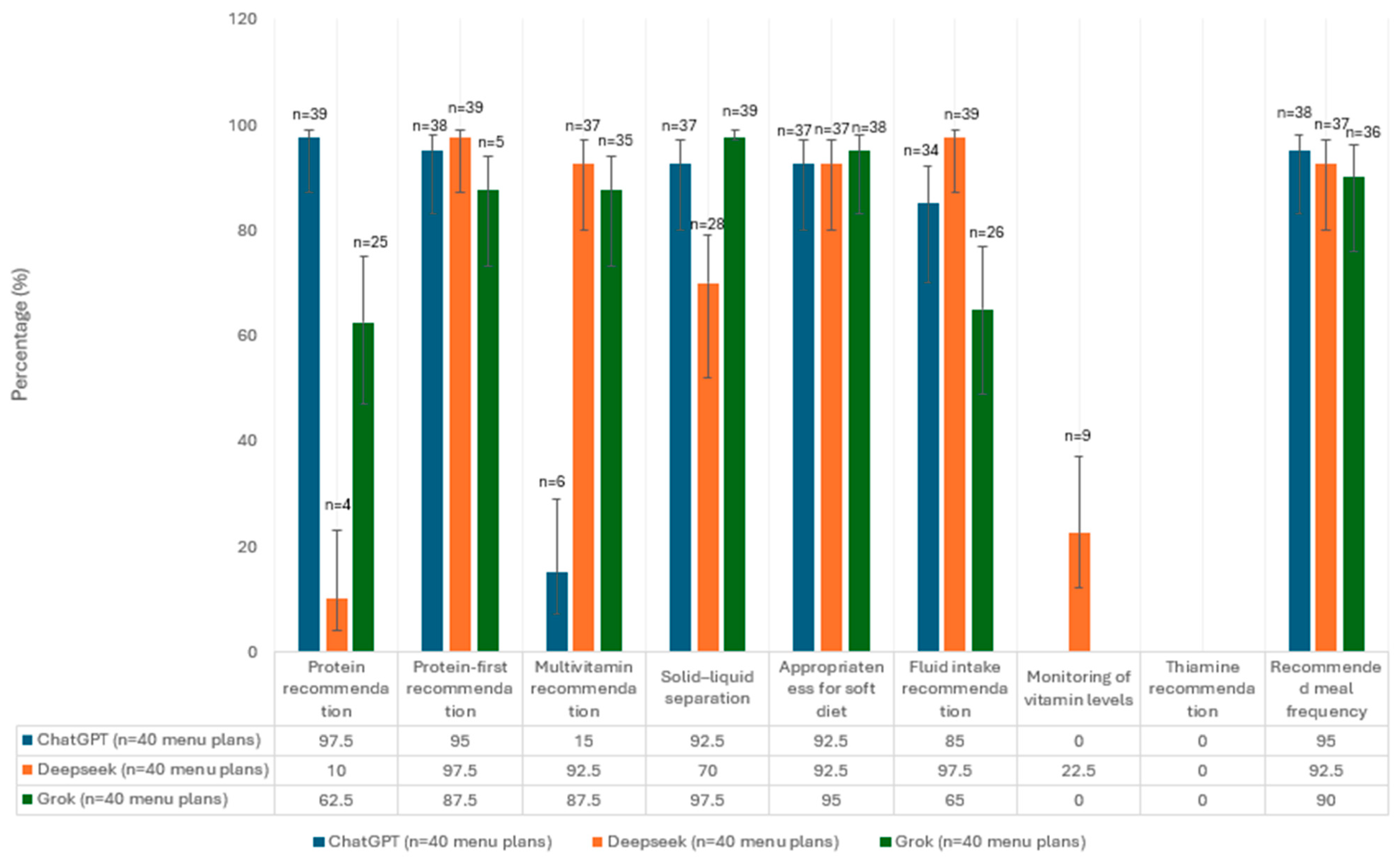

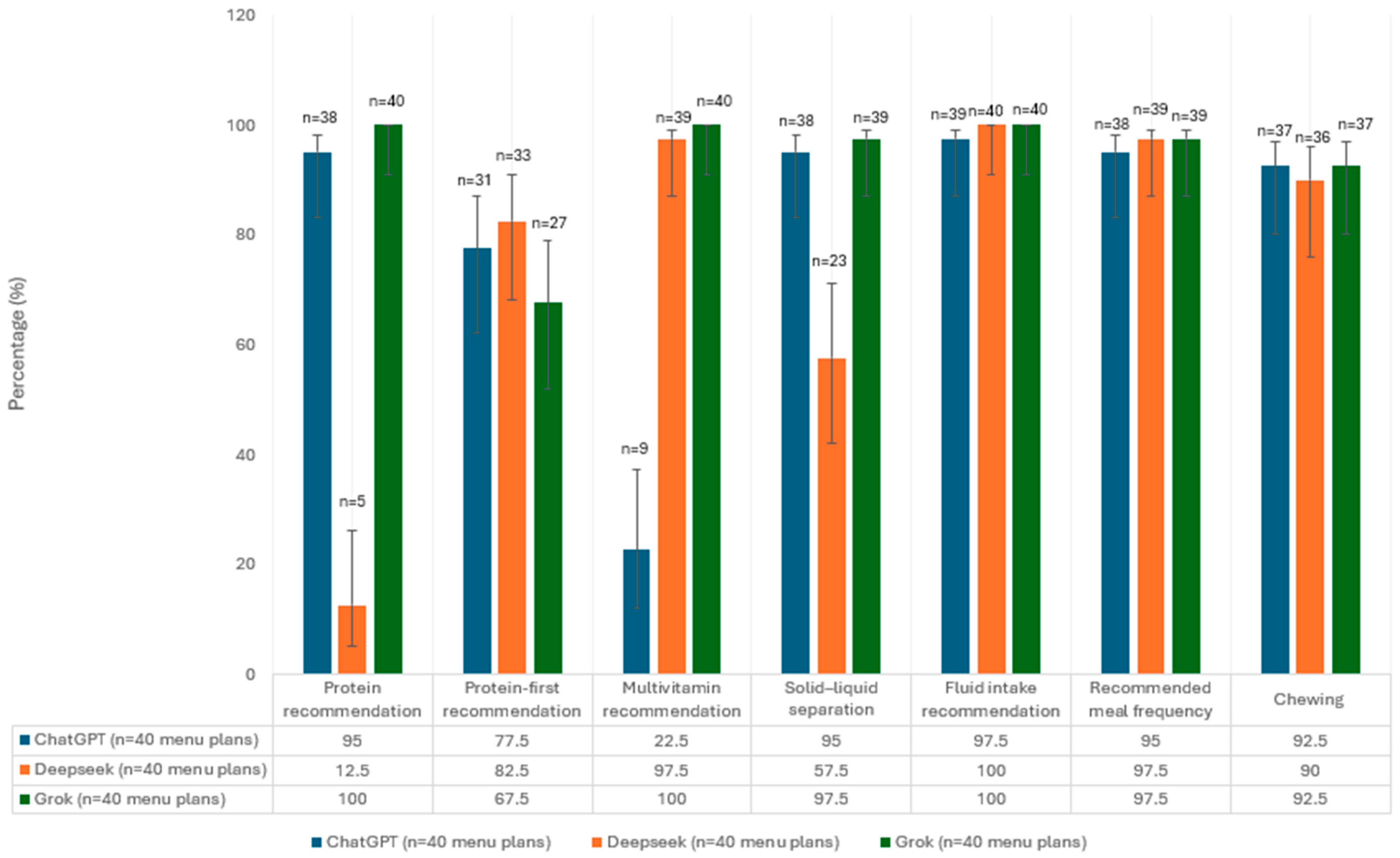

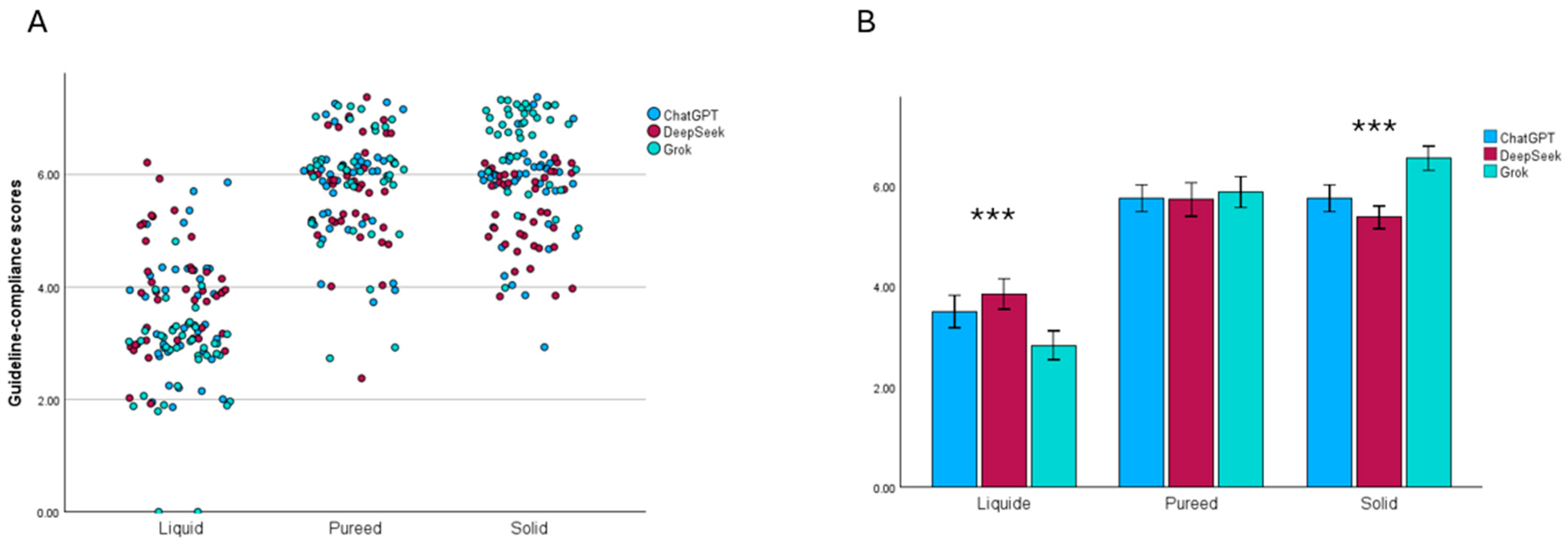

3.1. Evaluation of Menu Plans in Terms of Guideline Recommendations

3.2. Evaluation of the Energy and Macronutrient Contents of Menu Plans Based on AI Platforms

3.3. Evaluation of the Micronutrient Content of Menu Plans Based on AI Platforms

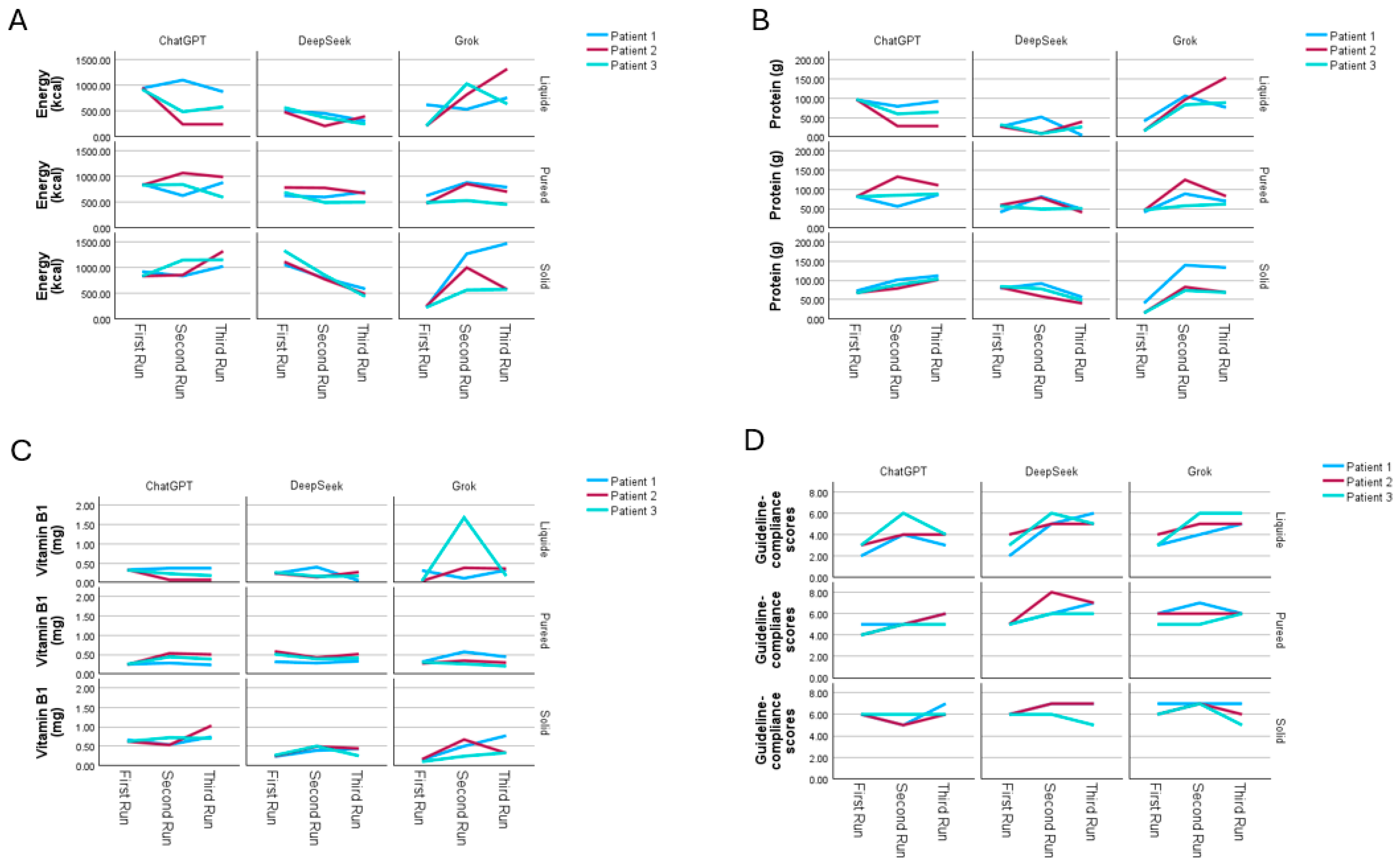

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Repeated Menu Generation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gadde, K.M.; Martin, C.K.; Berthoud, H.-R.; Heymsfield, S.B. Obesity. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxim, M.; Soroceanu, R.P.; Vlăsceanu, V.I.; Platon, R.L.; Toader, M.; Miler, A.A.; Onofriescu, A.; Abdulan, I.M.; Ciuntu, B.-M.; Balan, G.; et al. Dietary Habits, Obesity, and Bariatric Surgery: A Review of Impact and Interventions. Nutrients 2025, 17, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, I.; Kadota, A.; Miura, K.; Okamoto, M.; Nakamura, T.; Ikai, T.; Maegawa, H.; Ohnishi, A. Twelve-Year Trends of Increasing Overweight and Obesity in Patients with Diabetes: The Shiga Diabetes Clinical Survey. Endocr. J. 2018, 65, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ansari, W.; Elhag, W. Weight Regain and Insufficient Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery: Definitions, Prevalence, Mechanisms, Predictors, Prevention and Management Strategies, and Knowledge Gaps—A Scoping Review. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore Armand, T.P.; Nfor, K.A.; Kim, J.-I.; Kim, H.-C. Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning in Nutrition: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.W.; Park, J.S.; Sharma, K.; Velazquez, A.; Li, L.; Ostrominski, J.W.; Tran, T.; Seitter Peréz, R.H.; Shin, J.-H. Qualitative Evaluation of Artificial Intelligence-Generated Weight Management Diet Plans. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1374834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, D.; van Eijnatten, E.; Camps, G. Comparison of Answers between ChatGPT and Human Dieticians to Common Nutrition Questions. J. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 2023, 5548684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Brinsley, J.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Matricciani, L.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; Eglitis, E.; Miatke, A.; et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Chatbots on Lifestyle Behaviours. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozlu Karahan, T.; Kenger, E.B.; Yilmaz, Y. Artificial Intelligence-Based Diets: A Role in the Nutritional Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 38, e70033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fappa, E.; Micheli, M.; Panaretos, D.; Skordis, M.; Tsirpanli, P.; Panoutsopoulos, G.I. Human vs. AI: Assessing the Quality of Weight Loss Dietary Information Published on the Web. Information 2025, 16, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miler, A.A.; Visternicu, M.; Rarinca, V.; Stadoleanu, C.; Ciobica, A.; Maxim, M.; Toader, M.; Timofte, D.V.; Knieling, A. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Bariatric Surgery: Perspectives and Modern Applications. Brain 2025, 16, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Shin, T.; Tessier, L.; Javidan, A.; Jung, J.; Hong, D.; Strong, A.T.; McKechnie, T.; Malone, S.; Jin, D.; et al. Harnessing Artificial Intelligence in Bariatric Surgery: Comparative Analysis of ChatGPT-4, Bing, and Bard in Generating Clinician-Level Bariatric Surgery Recommendations. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2024, 20, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, H.M.; Ozturkcan, A. AI Showdown: Info Accuracy on Protein Quality Content in Foods from ChatGPT 3.5, ChatGPT 4, Bard AI and Bing Chat. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 3335–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Apovian, C.; Brethauer, S.; Garvey, W.T.; Joffe, A.M.; Kim, J.; Kushner, R.F.; Lindquist, R.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; Seger, J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutrition, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of Patients Undergoing Bariatric Procedures—2019 Update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, the Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Endocr. Pract. 2019, 25, 1346–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozlu Karahan, T.; Kenger, E.B. ChatGPT-4o for Weight Management: Comparison of Different Diet Models. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, H.M.; Arslan, S.; Ozturkcan, A. Evaluating AI-Generated Meal Plans for Simulated Diabetes Profiles: A Guideline-Based Comparison of Three Language Models. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2025, 31, e70295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batar, N. Nutrition Principles in Bariatric Surgery. Bakirkoy Tip Derg./Med. J. Bakirkoy 2019, 15, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabesh, M.R.; Eghtesadi, M.; Abolhasani, M.; Maleklou, F.; Ejtehadi, F.; Alizadeh, Z. Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Prescription of Supplements in Pre- and Post-Bariatric Surgery Patients: An Updated Comprehensive Practical Guideline. Obes. Surg. 2023, 33, 2557–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Kushner, R.F.; Sugerman, H.J.; Gonzalez-Campoy, J.M.; Collazo-Clavell, M.L.; Guven, S.; Spitz, A.F.; Apovian, C.M.; Livingston, E.H.; Brolin, R.; et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2008, 4, S109–S184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrazek, A.E.M.A.A.; Elbanna, A.E.M.; Bilasy, S.E. Medical Management of Patients after Bariatric Surgery: Principles and Guidelines. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014, 6, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busetto, L.; Dicker, D.; Azran, C.; Batterham, R.L.; Farpour-Lambert, N.; Fried, M.; Hjelmesæth, J.; Kinzl, J.; Leitner, D.R.; Makaronidis, J.M.; et al. Practical Recommendations of the Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity for the Post-Bariatric Surgery Medical Management. Obes. Facts 2017, 10, 597–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Semenova, Y.; Pivina, L.; Costea, D.-O. Follow-Up After Bariatric Surgery: A Review. Nutrition 2020, 78, 110831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moizé, V.; Andreu, A.; Rodríguez, L.; Flores, L.; Ibarzabal, A.; Lacy, A.; Jiménez, A.; Vidal, J. Protein Intake and Lean Tissue Mass Retention Following Bariatric Surgery. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, P.M.; Goodpaster, B.H. A Role for Exercise after Bariatric Surgery? Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2016, 18, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Youdim, A.; Jones, D.B.; Timothy Garvey, W.; Hurley, D.L.; Molly McMahon, M.; Heinberg, L.J.; Kushner, R.; Adams, T.D.; Shikora, S.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient—2013 Update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2013, 9, 159–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppert, J.; Bellicha, A.; Roda, C.; Bouillot, J.; Torcivia, A.; Clement, K.; Poitou, C.; Ciangura, C. Resistance Training and Protein Supplementation Increase Strength After Bariatric Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity 2018, 26, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderinto, N.; Olatunji, G.; Kokori, E.; Olaniyi, P.; Isarinade, T.; Yusuf, I.A. Recent Advances in Bariatric Surgery: A Narrative Review of Weight Loss Procedures. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 6091–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kane, M.; Parretti, H.M.; Pinkney, J.; Welbourn, R.; Hughes, C.A.; Mok, J.; Walker, N.; Thomas, D.; Devin, J.; Coulman, K.D.; et al. British Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society Guidelines on Perioperative and Postoperative Biochemical Monitoring and Micronutrient Replacement for Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery—2020 Update. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beek, A.P.; Emous, M.; Laville, M.; Tack, J. Dumping Syndrome after Esophageal, Gastric or Bariatric Surgery: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, S.; Calabrese, D.; Bogard, C.; Dupré, T.; Castel, B.; Msika, S.; Larger, E.; Coupaye, M. Long-Term Evolution of Nutritional Deficiencies After Gastric Bypass. Ann. Surg. 2014, 259, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, O.N.; Szomstein, S.; Rosenthal, R.J. Nutritional Consequences of Weight-Loss Surgery. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 91, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, B.S.; Finelli, F.C.; Shope, T.R.; Koch, T.R. Nutritional Deficiencies after Bariatric Surgery. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S. Decoding Dietary Myths: The Role of ChatGPT in Modern Nutrition. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 60, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettini, S.; Belligoli, A.; Fabris, R.; Busetto, L. Diet Approach before and after Bariatric Surgery. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, K. Nutritional Considerations After Bariatric Surgery. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2003, 26, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzo, V.; Goitre, I.; Favaro, E.; Merlo, F.D.; Mancino, M.V.; Riso, S.; Bo, S. Is ChatGPT an Effective Tool for Providing Dietary Advice? Nutrients 2024, 16, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introducing ChatGPT. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Wang, X.; Yin, M. Watch Out for Updates: Understanding the Effects of Model Explanation Updates in AI-Assisted Decision Making. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, C.M.; Pulker, C.E.; Meng, X.; Kerr, D.A.; Scott, J.A. Who Uses the Internet as a Source of Nutrition and Dietary Information? An Australian Population Perspective. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Shinozaki, N.; Okuhara, T.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Livingstone, M.B.E. Prevalence and Correlates of Dietary and Nutrition Information Seeking Through Various Web-Based and Offline Media Sources Among Japanese Adults: Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e54805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Guidance Data |

|---|

| A minimal protein intake of 60 g/d and up to 1.5 g/kg ideal weight per day should be adequate; higher amounts of protein intake—up to 2.1 g/kg ideal weight per day—need to be assessed on an individualized basis (Grade D). |

| A low-sugar, clear-liquid meal program can usually be initiated within 24 h after any of the surgical bariatric procedures, but this diet and meal progression should be discussed with the surgeon and guided by the registered dietician (RD) (Grade C; BEL 3). |

| A consultation for postoperative meal initiation and progression must be arranged with an RD who is knowledgeable about the postoperative bariatric diet (Grade A; BEL 1). |

| Patients should receive education in a protocol-derived staged meal progression based on their surgical procedure (Grade D). |

| Patients should be counseled to eat 3 small meals during the day and chew small bites of food thoroughly before swallowing (Grade D). |

| Patients should be counseled about the principles of healthy eating, including at least 5 daily servings of fresh fruits and vegetables (Grade D). |

| Protein intake should be individualized, assessed, and guided by an RD regarding sex, age, and weight (Grade D). |

| Minimal daily nutritional supplementation for patients with BPD with or without DS, RYGB, and SG should be in chewable form initially and then as 2 adult multivitamins plus minerals (each containing iron, folic acid, and thiamine) (Grade B; BEL 2). |

| 2000–3000 IU/day of vitamin D should be administered, titrated to maintain 25(OH)D levels > 30 ng/mL. (Grade A; BEL 1). |

| Total iron as 18 to 60 mg via multivitamins and additional supplements (Grade A, BEL 1). |

| Vitamin B12 (parenterally as sublingual, subcutaneous, or intramuscular preparations; orally if determined to be adequately absorbed) (Grade B; BEL 2). |

| Once patients can tolerate orals, fluids should be consumed slowly, preferably at least 30 min after meals to prevent GI symptoms, and in sufficient amounts to maintain adequate hydration (>1.5 L daily) (Grade D). |

| The postoperative follow-up checklist includes maintaining adequate hydration (usually >1.5 L/day orally); 24 h urinary calcium excretion at 6 months and then annually; annual vitamin B12 monitoring (with optional MMA and homocysteine testing, and every 3–6 months if the patient is receiving supplementation); assessment of folic acid (with optional RBC folate), iron studies, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and iPTH; vitamin A measurement initially and then every 6–12 months; evaluation of copper, zinc, and selenium when clinically indicated; and thiamine assessment in the presence of relevant symptoms or risk factors. |

| All post-WLS patients should take at least 12 mg thiamine daily (Grade C; BEL 3). |

| Suggestion | Period | Explanation | Present (1 Score) | Absent (0 Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriateness for full-liquid diet | Liquid | If the menu provided for Day 5 consists solely of liquids. | ||

| Iron supplementation | Liquid | Use a multivitamin with iron. | ||

| Appropriateness for soft diet | Pureed | List of soft, easy-to-chew foods | ||

| Chewing | Solid | Bites should be thoroughly chewed | ||

| Protein-first recommendation | Pureed, solid | During the solid phase, start each meal with protein to meet your needs. | ||

| Recommended meal frequency | Pureed, solid | Consume 3 small meals. | ||

| Monitoring of vitamin levels | Liquid, pureed | Have your vitamin and mineral levels checked regularly. | ||

| Thiamine recommendation | Liquid, pureed | Use multivitamin with thiamine | ||

| Protein recommendation | Liquid, pureed, solid | Aim for at least 60 g of protein per day | ||

| Multivitamin recommendation | Liquid, pureed, solid | Take a daily multivitamin. A single vitamin recommendation does not constitute a multivitamin. | ||

| Solid–liquid separation | Liquid, pureed, solid | Stop fluids 30 min before and after meals | ||

| Fluid intake recommendation | Liquid, pureed, solid | Aim for at least 1.5 L fluids daily. | ||

| Maximum Score | ||||

| Liquid | 8 | |||

| Pureed | 9 | |||

| Solid | 7 |

| ChatGPT | DeepSeek | Grok | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | Day 5 | 831.4 (655.3–926.3) | 742.1 (530.9–877.7) | 240.4 (214.3–246.9) | <0.001 β,† |

| Day 16 | 833.1 (731.7–893.4) | 1015.8 (810.1–1073.5) | 532.4 (467.7–636.4) | <0.001 α,β,† | |

| Day 35 | 978.8 (825.1–1131.3) | 1063.3 (972.2–1235.3) | 730.4 (306.6–805.9) | <0.001 α,β,† | |

| Protein (g) | Day 5 | 70.2 (53.3–73.6) | 41.6 (27.4–49.5) | 19.6 (15.6–19.7) | <0.001 α,β,† |

| Day 16 | 71.1 (59.7–81.4) | 74.9 (64.2–85.7) | 47.1 (45.2–49.5) | <0.001 β,† | |

| Day 35 | 71.6 (66.8–82.8) | 77.4 (72.6–83.5) | 69.6 (35.8–70.1) | <0.001 β,† | |

| Protein (%) | Day 5 | 34.0 (29.2–42.0) | 23.0 (14.3–27.5) | 33.0 (28.0–33.0) | |

| Day 16 | 37.0 (30.2–40.0) | 32.0 (26.2–36.0) | 38.0 (31.0–40.0) | ||

| Day 35 | 31.0 (29.0–34.0) | 28.0 (27.0–31.0) | 40.0 (35.2–46.0) | ||

| Fat (g) | Day 5 | 19.6 (18.1–25.0) | 18.6 (12.3–25.7) | 6.5 (3.4–6.6) | |

| Day 16 | 36.3 (26.2–42.9) | 43.9 (29.8–69.5) | 17.2 (14.9–19.0) | ||

| Day 35 | 48.8 (43.3–59.2) | 59.7 (42.8–68.2) | 31.5 (10.2–37.6) | ||

| Fat (%) | Day 5 | 22.5 (19.0–28.2) | 22.5 (14.3–33.0) | 24.0 (19.0–24.75) | |

| Day 16 | 40.0 (34.2–43.7) | 43.5 (36.5–59.0) | 31.0 (25.0–34.7) | ||

| Day 35 | 47.0 (43.0–49.0) | 47.0 (39.0–58.0) | 36.5 (30.0–43.0) | ||

| CHO (g) | Day 5 | 78.1 (41.5–96.9) | 94.4 (56.4–116.8) | 25.7 (22.5–28.7) | |

| Day 16 | 46.3 (34.8–61.4) | 49.3 (35.5–54.1) | 40.0 (32.6–68.1) | ||

| Day 35 | 52.1 (36.3–62.1) | 59.4 (36.9–77.4) | 30.4 (20.4–56.2) | ||

| CHO (%) | Day 5 | 38.5 (30.0–50.5) | 46.5 (38.3–69.0) | 43.0 (41.0–59.8) | |

| Day 16 | 24.0 (18.2–30.2) | 21.0 (14.0–27.7) | 31.5 (26.2–44.7) | ||

| Day 35 | 21.0 (17.0–26.0) | 22.0 (14.5–29.0) | 25.5 (16.0–29.7) | ||

| Fiber (g) | Day 5 | 2.4 (1.3–4.8) | 3.3 (2.8–7.2) | 0.47 (0.45–0.56) | |

| Day 16 | 5.6 (3.2–6.8) | 12.6 (8.5–13.3) | 4.4 (3.2–4.9) | ||

| Day 35 | 8.2 (6.6–9.7) | 14.4 (13.0–17.6) | 4.1 (2.3–4.4) | ||

| Cholesterol (mg) | Day 5 | 47.8 (40.0–59.6) | 65.0 (28.7–91.49 | 12.0 (6.0–13.0) | |

| Day 16 | 363.8 (126.2–451.0) | 235.6 (204.9–442.5) | 96.1 (92.1–136.0) | ||

| Day 35 | 432.1 (401.0–464.5) | 408.9 (379.2–426.1) | 429.4 (356.7–439.3) |

| ChatGPT | DeepSeek | Grok | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | Day 5 | 0.33 (0.29–0.36) | 0.33 (0.21–0.44) | 0.11 (0.08–0.10) | <0.001 β,† |

| Day 16 | 0.38 (0.32–0.46) | 0.57 (0.49–0.62) | 0.29 (0.28–0.31) | <0.001 α,β,† | |

| Day 35 | 0.62 (0.52–0.65) | 0.67 (0.58–0.71) | 0.35 (0.17–0.36) | <0.001 α,β,† | |

| Folic acid (µg) | Day 5 | 79.3 (61.7–86.8) | 74.2 (53.5–103.9) | 21.6 (16.5–23.2) | |

| Day 16 | 104.1 (93.8–132.6) | 145.1 (131.4–168.8) | 82.4 (61.2–94.4) | ||

| Day 35 | 172.8 (148.7–188.6) | 176.4 (148.2–209.1) | 110.5 (89.1–131.9) | ||

| Vitamin C (mg) | Day 5 | 28.1 (18.8–49.0) | 42.7 (26.7–63.8) | 12.8 (10.9–12.9) | |

| Day 16 | 38.3 (29.4–47.4) | 47.9 (35.1–57.5) | 47.0 (23.2–54.4) | ||

| Day 35 | 63.9 (57.8–70.8) | 45.8 (38.1–60.2) | 38.7 (22.3–42.3) | ||

| Calcium (mg) | Day 5 | 676.0 (598.1–861.1) | 519.6 (394.7–745.9) | 244.0 (158.1–244.0) | |

| Day 16 | 641.7 (567.6–875.1) | 769.6 (665.2–828.7) | 397.1 (324.8–415.6) | ||

| Day 35 | 849.8 (689.1–943.1) | 824.3 (684.7–1060.4) | 416.3 (376.6–476.3) | ||

| Iron (mg) | Day 5 | 2.1 (1.4–2.6) | 2.4 (1.5–3.4) | 0.52 (0.44–0.55) | |

| Day 16 | 3.0 (2.4–3.3) | 4.7 (3.5–5.6) | 1.6 (1.5–2.7) | ||

| Day 35 | 4.2 (3.6–5.1) | 5.8 (4.9–6.2) | 2.8 (1.5–2.9) | ||

| Zinc (mg) | Day 5 | 3.4 (2.7–4.0) | 2.9 (2.0–6.8) | 0.95 (0.85–1.3) | |

| Day 16 | 4.5 (3.2–4.8) | 4.9 (4.3–5.7) | 1.9 (1.6–2.5) | ||

| Day 35 | 5.9 (4.9–7.6) | 6.2 (5.3–7.4) | 3.7 (1.6–3.8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bolat Yilmaz, A.; Kenger, E.B.; Ozlu Karahan, T.; Saglam, D.; Bas, M. Guideline Compliance of Artificial Intelligence–Generated Diet Plans After Bariatric Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Simulation Comparing ChatGPT-4o, DeepSeek and Grok-3. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243957

Bolat Yilmaz A, Kenger EB, Ozlu Karahan T, Saglam D, Bas M. Guideline Compliance of Artificial Intelligence–Generated Diet Plans After Bariatric Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Simulation Comparing ChatGPT-4o, DeepSeek and Grok-3. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243957

Chicago/Turabian StyleBolat Yilmaz, Aylin, Emre Batuhan Kenger, Tugce Ozlu Karahan, Duygu Saglam, and Murat Bas. 2025. "Guideline Compliance of Artificial Intelligence–Generated Diet Plans After Bariatric Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Simulation Comparing ChatGPT-4o, DeepSeek and Grok-3" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243957

APA StyleBolat Yilmaz, A., Kenger, E. B., Ozlu Karahan, T., Saglam, D., & Bas, M. (2025). Guideline Compliance of Artificial Intelligence–Generated Diet Plans After Bariatric Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Simulation Comparing ChatGPT-4o, DeepSeek and Grok-3. Nutrients, 17(24), 3957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243957