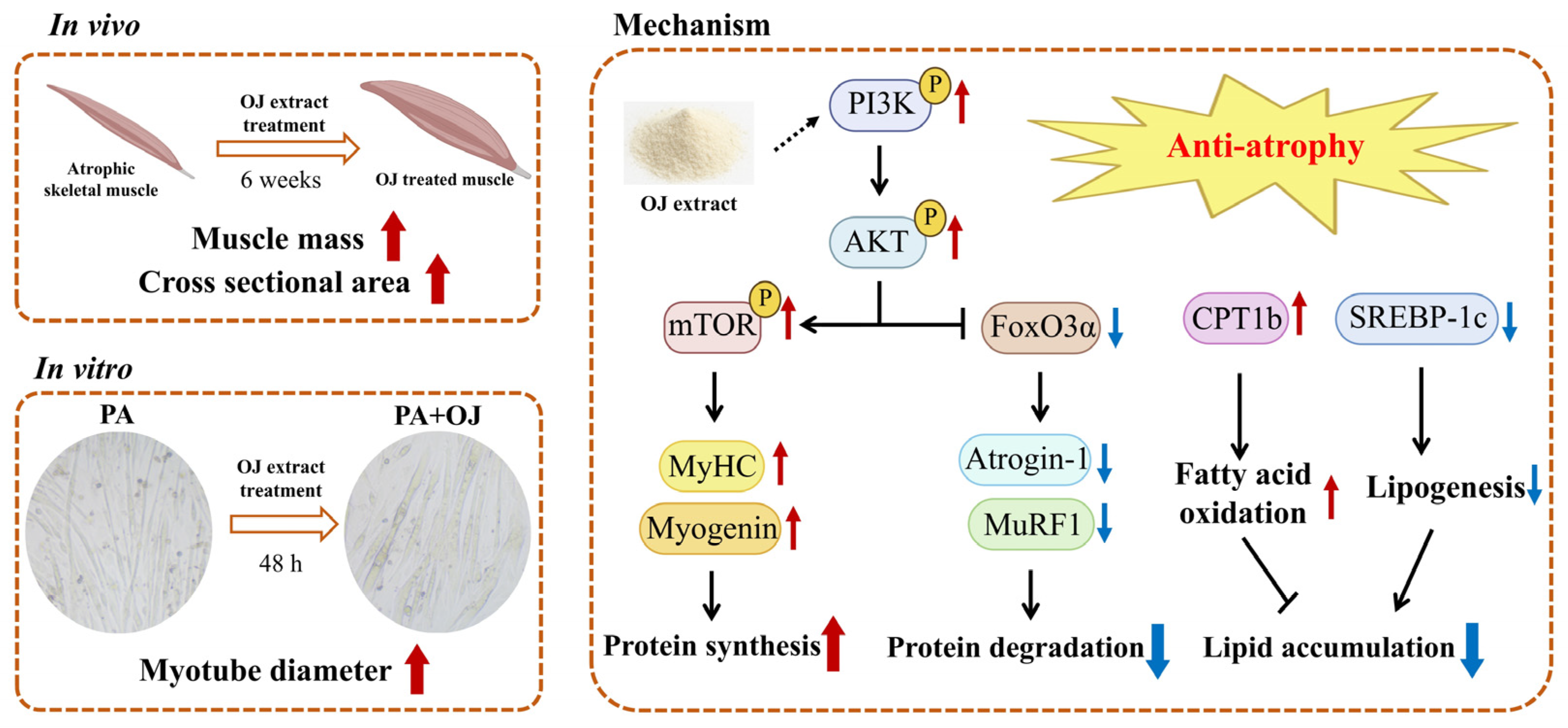

Ophiopogon japonicus Root Extract Attenuates Obesity-Induced Muscle Atrophy Through Regulation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR/FoxO3a Signaling Pathway and Lipid Metabolism in Mice and C2C12 Myotubes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of OJ Extract

2.2. Preparation of Animal Model

2.3. Measurement of Grip Strength

2.4. Hanging Time Test

2.5. Glucose Tolerance and Insulin Resistance Tests

2.6. Histopathological Analysis

2.7. Analysis of Serological Parameters

2.8. C2C12 Cell Cultures and Treatment

2.9. Cell Viability Analysis

2.10. Immunocytochemistry

2.11. Oil Red O Staining

2.12. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.13. Western Blotting Analysis

2.14. Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography–Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS)

2.15. Network Pharmacology Analysis

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. OJ Extract Ameliorated Obesity-Induced Muscle Atrophy in Mice

3.2. OJ Extract Improved Glucose Tolerance, Insulin Resistance, and Dyslipidemia in Obesity-Induced Muscle Atrophy Mice

3.3. OJ Extract Modulated the PI3K-AKT-mTOR/FoxO3a Signaling and Lipid Metabolism in Muscle Tissues of Obesity-Induced Muscle Atrophy Mice

3.4. OJ Extract Alleviated PA-Induced Atrophy in C2C12 Myotubes

3.5. OJ Extract Regulated the PI3K-AKT-mTOR/FoxO3a Signaling in PA-Stimulated C2C12 Myotubes

3.6. OJ Extract Improved Lipid Metabolism in PA-Stimulated C2C12 Myotubes

3.7. UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS Analysis of OJ Extract

3.8. Network Pharmacological Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caturano, A.; Amaro, A.; Berra, C.C.; Conte, C. Sarcopenic obesity and weight loss-induced muscle mass loss. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2025, 28, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, E.; Pinel, A.; Guillet, C.; Capel, F.; Pereira, B.; De Antonio, M.; Pouget, M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Eglseer, D.; Topinkova, E.; et al. Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity and Mortality Among Older People. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e243604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, L.; Robinson, M.; Geetha, T.; Broderick, T.L.; Babu, J.R. Prevalence and Mechanisms of Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Metabolic Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Mei, F.; Shang, Y.; Hu, K.; Chen, F.; Zhao, L.; Ma, B. Global prevalence of sarcopenic obesity in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4633–4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, S.; Xu, L.; Zhao, X.; Han, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Han, B. Prevalence of sarcopenic obesity in the older non-hospitalized population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Tan, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, X.; Liao, Z.; Wei, P. Diabetes and Sarcopenic Obesity: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatments. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesinovic, J.; Fyfe, J.J.; Talevski, J.; Wheeler, M.J.; Leung, G.K.W.; George, E.S.; Hunegnaw, M.T.; Glavas, C.; Jansons, P.; Daly, R.M.; et al. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Sarcopenia as Comorbid Chronic Diseases in Older Adults: Established and Emerging Treatments and Therapies. Diabetes Metab. J. 2023, 47, 719–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Jiao, Q.; Li, Q.; Jiang, W. Metabolites of traditional Chinese medicine targeting PI3K/AKT signaling pathway for hypoglycemic effect in type 2 diabetes. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1373711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, Z.; Petito, G.; Shitaye, G.; D’Abrosca, G.; Legesse, B.A.; Addisu, S.; Ragni, M.; Lanni, A.; Fattorusso, R.; Isernia, C.; et al. Insulin-Sensitizing Properties of Decoctions from Leaves, Stems, and Roots of Cucumis prophetarum L. Molecules 2024, 30, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sknepnek, A.; Miletic, D.; Stupar, A.; Salevic-Jelic, A.; Nedovic, V.; Cvetanovic Kljakic, A. Natural solutions for diabetes: The therapeutic potential of plants and mushrooms. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1511049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H.; Chen, X.J.; Wang, M.; Lin, L.G.; Wang, Y.T. Ophiopogon japonicus—A phytochemical, ethnomedicinal and pharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 181, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.S.; Sisodia, S.S. Phytochemical Screening, Characterization and Formulation and Evaluation of Herbal Gel of Abelmoschus Manihot for Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Pharm. Qual. Assur. 2024, 9, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.W.; Chen, D.S.; Deng, C.S.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, W.; Lin, L. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of compounds isolated from the rhizome of Ophiopogon japonicas. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xue, J. Extraction, purification, structural characterization, bioactivities, modifications and structure-activity relationship of polysaccharides from Ophiopogon japonicus: A review. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1484865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, E.; Chen, X. Cardioprotective effect of the polysaccharide from Ophiopogon japonicus on isoproterenol-induced myocardial ischemia in rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, B.; Peng, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, J. Quality Evaluation of Ophiopogon japonicus from Two Authentic Geographical Origins in China Based on Physicochemical and Pharmacological Properties of Their Polysaccharides. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Xiao, Z. Advances in the study of Ophiopogon japonicus polysaccharides: Structural characterization, bioactivity and gut microbiota modulation regulation. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1583711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Ma, Q.; Chen, T.; Zhang, H.; Ma, G.; Mafu, S.; Guo, J.; Fan, X.; Cui, G.; Jin, B. Functional characterization of seven terpene synthases from Ophiopogon japonicus via engineered Escherichia coli. Sci. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2024, 2, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ruan, K.; Wei, H.; Feng, Y. MDG-1, a polysaccharide from Ophiopogon japonicus, prevents high fat diet-induced obesity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 114, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Tian, X.Y.; Mao, D.; Hung, S.W.; Wang, C.C.; Lau, C.B.S.; Lee, H.M.; Wong, C.K.; Chow, E.; Ming, X.; et al. A polysaccharide extract from the medicinal plant Maidong inhibits the IKK-NF-kappaB pathway and IL-1beta-induced islet inflammation and increases insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 12573–12587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D.S.; Ruan, K.F.; Feng, Y.; Wang, S. Hypoglycemic effects of MDG-1, a polysaccharide derived from Ophiopogon japonicas, in the ob/ob mouse model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 49, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.D.; Farooqi, I.S.; Friedman, J.M.; Klein, S.; Loos, R.J.F.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; O’Rahilly, S.; Ravussin, E.; Redman, L.M.; Ryan, D.H.; et al. The energy balance model of obesity: Beyond calories in, calories out. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, A.; den Hartigh, L.J. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meex, R.C.R.; Blaak, E.E.; van Loon, L.J.C. Lipotoxicity plays a key role in the development of both insulin resistance and muscle atrophy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binmahfoz, A.; Dighriri, A.; Gray, C.; Gray, S.R. Effect of resistance exercise on body composition, muscle strength and cardiometabolic health during dietary weight loss in people living with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2025, 11, e002363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L. The structures and biological functions of polysaccharides from traditional Chinese herbs. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 163, 423–444. [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod, C.L.; Dantas, W.S.; Kirwan, J.P. Sarcopenic obesity: Emerging mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Metabolism 2023, 146, 155639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greggi, C.; Montanaro, M.; Scioli, M.G.; Puzzuoli, M.; Gino Grillo, S.; Scimeca, M.; Mauriello, A.; Orlandi, A.; Gasbarra, E.; Iundusi, R.; et al. Modulation of Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase 1b Expression and Activity in Muscle Pathophysiology in Osteoarthritis and Osteoporosis. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, R.; Romanello, V.; Sandri, M. Mechanisms of muscle atrophy and hypertrophy: Implications in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, X.; Liu, W. Ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in skeletal muscle atrophy. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1289537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris-Moreno, D.; Taillandier, D.; Polge, C. MuRF1/TRIM63, Master Regulator of Muscle Mass. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szliszka, E.; Czuba, Z.P.; Domino, M.; Mazur, B.; Zydowicz, G.; Krol, W. Ethanolic extract of propolis (EEP) enhances the apoptosis- inducing potential of TRAIL in cancer cells. Molecules 2009, 14, 738–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Gao, P.; Li, Z.; Dai, A.; Yang, M.; Chen, S.; Su, J.; Deng, Z.; Li, L. Forkhead Box O Signaling Pathway in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Am. J. Pathol. 2022, 192, 1648–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolaro, F.; Ghaem-Maghami, S.; Bortolozzi, R.; Zona, S.; Khongkow, M.; Basso, G.; Viola, G.; Lam, E.W. FOXO3a and Posttranslational Modifications Mediate Glucocorticoid Sensitivity in B-ALL. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 1578–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirago, G.; Picca, A.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Marzetti, E. Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Signaling at the Crossroad of Muscle Fiber Fate in Sarcopenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, I.M.P.; Argiles, J.M.; Rueda, R.; Ramirez, M.; Pedrosa, J.M.L. Skeletal muscle atrophy and dysfunction in obesity and type-2 diabetes mellitus: Myocellular mechanisms involved. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2025, 26, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, M.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, H.; Zhou, S.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Fatty infiltration in the musculoskeletal system: Pathological mechanisms and clinical implications. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1406046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.J.; Choung, S.Y. Codonopsis lanceolata ameliorates sarcopenic obesity via recovering PI3K/Akt pathway and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle. Phytomedicine 2022, 96, 153877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of SCAP/SREBP as Central Regulators of Lipid Metabolism in Hepatic Steatosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, N.; Janezic, E.G.; Sink, Z.; Ugwoke, C.K. Crosstalk Between Skeletal Muscle and Proximal Connective Tissues in Lipid Dysregulation in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Metabolites 2025, 15, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Zhang, W. Role of mTOR in Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chi, X.; Wang, Y.; Setrerrahmane, S.; Xie, W.; Xu, H. Trends in insulin resistance: Insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q.; Zheng, K.; Li, W.; An, K.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Hai, S.; Dong, B.; Li, S.; An, Z.; et al. Post-translational regulation of muscle growth, muscle aging and sarcopenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1212–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodine, S.C. The role of mTORC1 in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass. Fac. Rev. 2022, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, C.; Han, X. Ophiopogonin D alleviates high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome and changes the structure of gut microbiota in mice. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 1139–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Xu, B.L.; Chen, C.; Jia, H.J.; Wu, J.X.; Wang, X.C.; Sheng, J.L.; Huang, L.; Cheng, J. Methylophiopogonanone A suppresses ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial apoptosis in mice via activating PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Shao, H.; Lyu, C.; Park, K.H.; Nguyen, T.K.; Yang, I.J.; Jung, H.W.; Park, Y.-K. Ophiopogon japonicus Root Extract Attenuates Obesity-Induced Muscle Atrophy Through Regulation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR/FoxO3a Signaling Pathway and Lipid Metabolism in Mice and C2C12 Myotubes. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243946

Wang Y, Shao H, Lyu C, Park KH, Nguyen TK, Yang IJ, Jung HW, Park Y-K. Ophiopogon japonicus Root Extract Attenuates Obesity-Induced Muscle Atrophy Through Regulation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR/FoxO3a Signaling Pathway and Lipid Metabolism in Mice and C2C12 Myotubes. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243946

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yang, Haifeng Shao, Chenzi Lyu, Kyung Hee Park, Tran Khoa Nguyen, In Jun Yang, Hyo Won Jung, and Yong-Ki Park. 2025. "Ophiopogon japonicus Root Extract Attenuates Obesity-Induced Muscle Atrophy Through Regulation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR/FoxO3a Signaling Pathway and Lipid Metabolism in Mice and C2C12 Myotubes" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243946

APA StyleWang, Y., Shao, H., Lyu, C., Park, K. H., Nguyen, T. K., Yang, I. J., Jung, H. W., & Park, Y.-K. (2025). Ophiopogon japonicus Root Extract Attenuates Obesity-Induced Muscle Atrophy Through Regulation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR/FoxO3a Signaling Pathway and Lipid Metabolism in Mice and C2C12 Myotubes. Nutrients, 17(24), 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243946