Plant Oils in Sport Nutrition: A Narrative Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Which plant taxa are sources of oils in patented alimentary products dedicated to sportspeople?

- 2.

- What is the consistency, form, and activity of the above-mentioned products?

- 3.

- What is the impact of plant oils on the performance and health of sportspeople?

- 4.

- What is the frequency of use of plant oils by sportspeople?

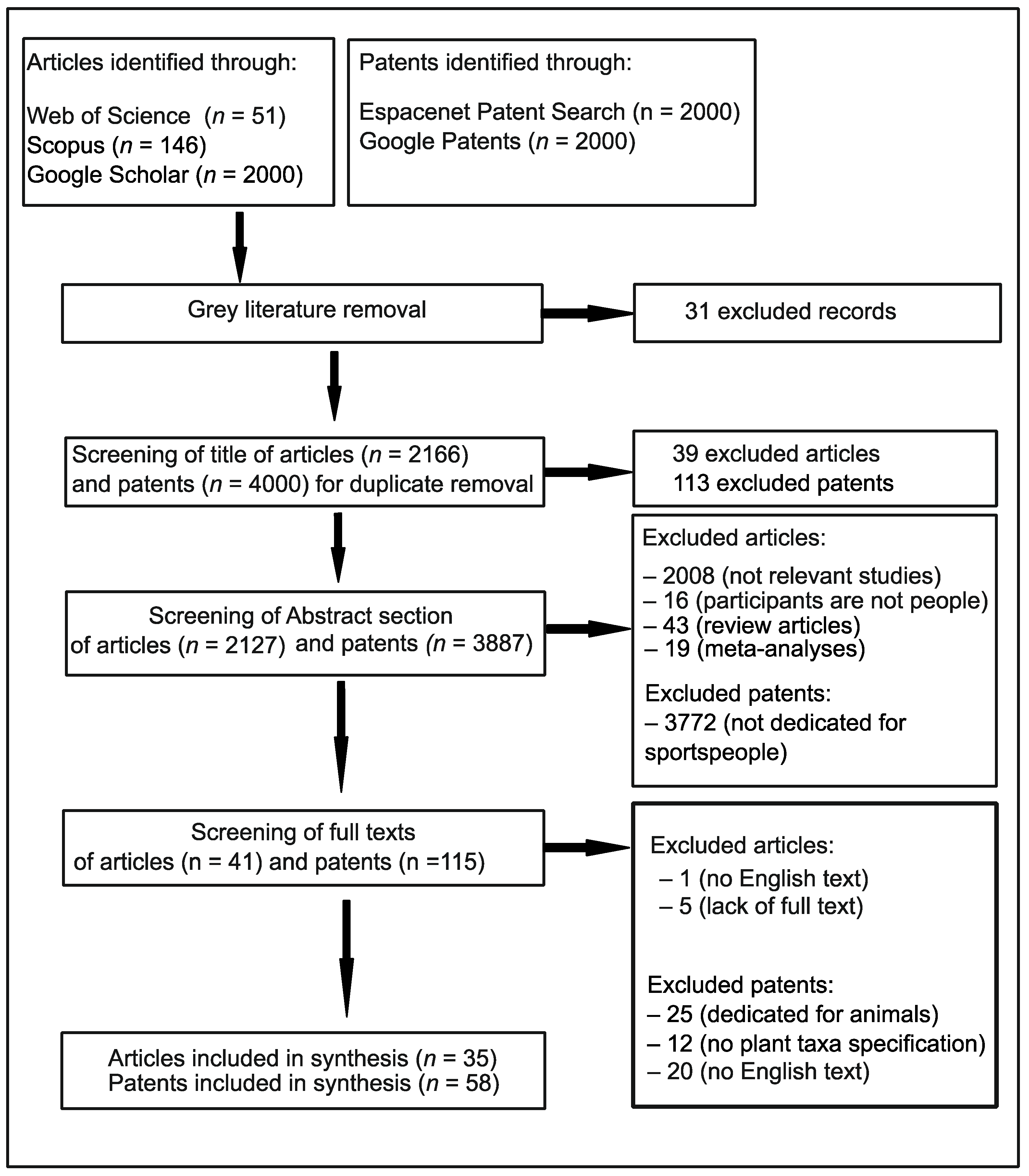

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Study Eligibility and Selection

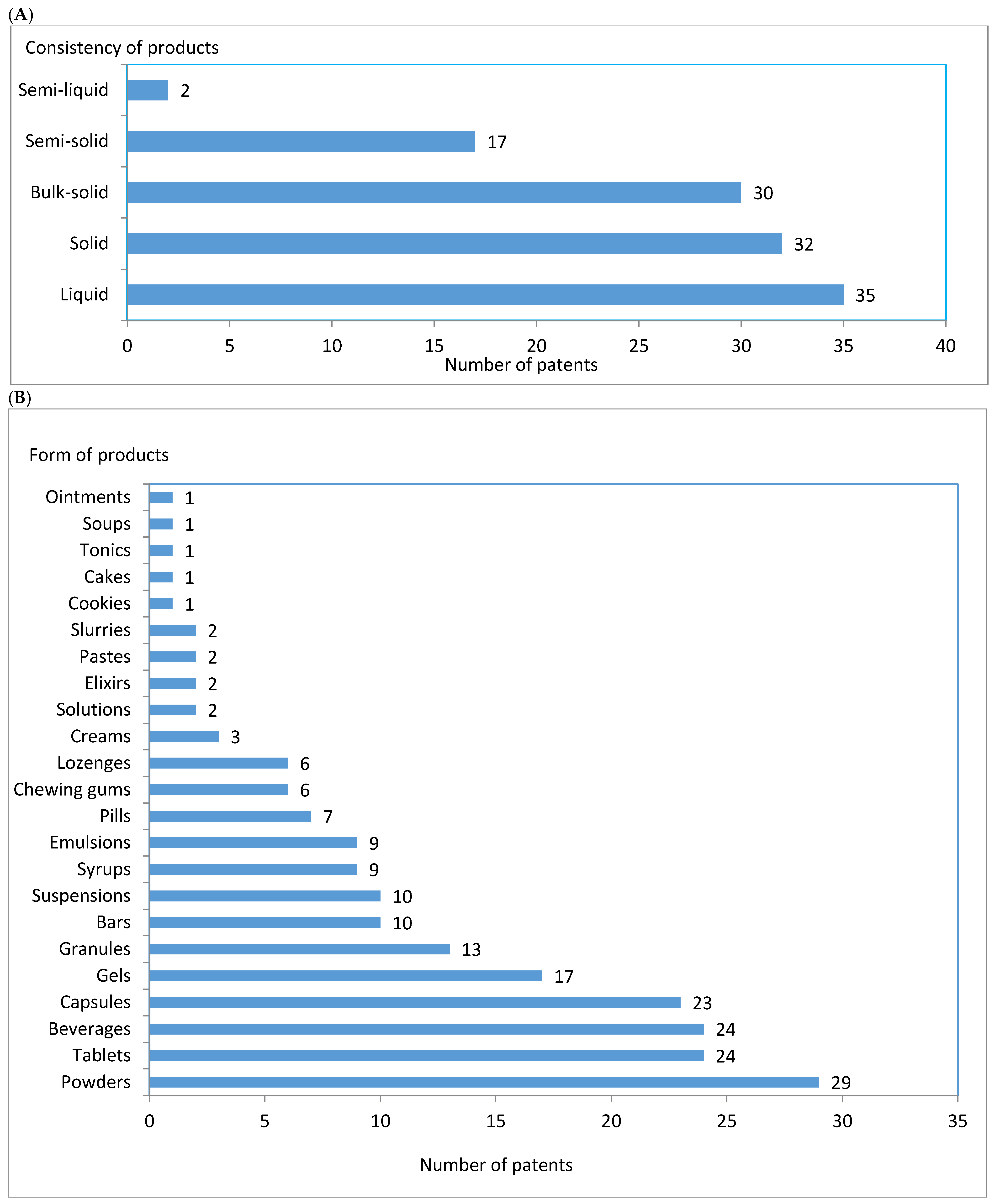

3. Results

3.1. Plant Taxa as Sources of Oils Used in Sports Food and Drinks

3.2. The Impact of Plant Oils on the Performance and Health of Sportspeople

3.3. The Frequency of Use and Sensory Acceptability of Food Products Containing Plant Oils by Sportspeople

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Main Inventor Name | Patent Title | Plant Species | Activity | Consistency (Form) of Invention | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Amyx, L. | Sports and nutritional supplement formulations | Brassica napus L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Zea mays L. | Muscle strength improvement; sports performance improvement | Liquid (beverage and suspension), solid (capsules, tablets, and lozenges), semi-solid (gel), and bulk-solid (powder) | [48] |

| 2. | Andreeva, L. | Nutritional compositions for skeletal muscle | Arachis hypogaea L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Olea europaea L Zea mays L. | Muscle strength improvement | Liquid (beverage) | [49] |

| 3. | Asada, M. | Sports drink | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Olea europaea L Oryza sativa L. Zea mays L. | Nutrition | Liquid (beverage) | [50] |

| 4. | Barata, M. | Nutritional formulations comprising a pea protein isolate | Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Helianthus annuus L. Olea europaea L Vitis vinifera L. Zea mays L. | Nutrition and weight loss | Solid (bar, cakes, and cookies), bulk-solid (powder), and liquid (beverage) | [51] |

| 5. | Bartos, J.D. | Endurance formulation and use | Olea europaea L. | Endurance improvement | Liquid (beverage, syrup, and emulsion), solid (capsules, tablets, lozenges, chewing gum, and bars), semi-solid (gel), and bulk-solid (powder) | [52] |

| 6. | Bermond, G. | Compositions for the improvement of sports performance | Arachis hypogaea L. Cocos nucifera L. Olea europaea L. Sesamum indicum L. | Sports performance improvement | Solid (capsules, tablets, and lozenges), bulk-solid (powder and granules), and liquid (emulsion and syrup) | [53] |

| 7. | Billecke, N. | Nutritional composition and process for preparing it | Arachis hypogaea L. Bertholletia excelsa Humb. & Bonpl. Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Coriandrum sativum L. Corylus avellana L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Juglans major (Torr.) A. Heller Linum usitatissimum L. Olea europaea L Persea americana Mill. Ricinus communis L. Sesamum indicum L. Sinapis alba L. Zea mays L. | Nutrition | Liquid (beverage) and bulk-solid (powder) | [54] |

| 8. | Bortz, J.D. | Composition for improved performance | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Cannabis sativa L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Linum usitatissimum L. Olea europaea L. Triticum aestivum L. Zea mays L. | Sports performance improvement | Liquid (beverage), solid (tablets and capsules), semi-solid (gel), and bulk-solid (powder) | [55] |

| 9. | Bos, P. | Novel combinations comprising konjac mannan, and their compositions and uses | Borago officinalis L. Cocos nucifera L. Linum usitatissimum L. Oenothera biennis L. Olea europaea L. Ribes nigrum L. | Weight loss | Bulk-solid (powder and granules) | [56] |

| 10. | Burke, L.M. | Method of enhancing muscle protein synthesis | Brassica napus L. Helianthus annuus L. Zea mays L. | Muscle mass increase | Liquid (beverage), semi-solid (gel), and bulk-solid (powder) | [57] |

| 11. | Do, P.P. | Composition and method for nutrition formulation | Anacardium occidentale L. Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) K.Koch Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai Cocos nucifera L. Fagus sylvatica L. Gossypium arboreum L. Helianthus annuus L. Juglans regia L. Olea europaea L. Persea americana Mill. Pistacia vera L. Prunus amygdalus Batsch Sesamum indicum L. Vitis vinifera L | Sport performance improvement and post-exercise recovery support | Liquid (beverage) and solid (bar) | [58] |

| 12. | Du, Y. | Instant soybean protein composition and preparation method | Cocos nucifera L. Helianthus annuus L. Linum usitatissimum L. | Nutrition | Bulk-solid (powder) | [59] |

| 13. | Dyrvig, M. | Neutral instant beverage whey protein powder | Brassica napus L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. | Nutrition | Bulk-solid (powder) | [60] |

| 14. | Feng, W. | Compositions for post-exercise recovery and methods of making and using | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Juglans regia L. Linum usitatissimum L. Olea europaea L. Prunus amygdalus Batsch Salvia hispanica L. Sesamum indicum L. Vitis vinifera L. Zea mays L. | Post-exercise recovery support | Solid (chewing gum) and semi-solid (gel) | [61] |

| 15. | Francis, C. | Methods and compositions comprising caffeine and/or a derivative and a polyphenol | Brassica napus L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Olea europaea L. Prunus amygdalus Batsch Ribes nigrum L. Sesamum indicum L. Zea mays L. | Cognitive function improvement | Liquid (beverage), solid (chewing gum, tablets, and capsules), semi-solid (gel), and bulk-solid (powder and granules) | [62] |

| 16. | Franse, M.M. | Protein bar | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz Carthamus tinctorius L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Olea europaea L. Oryza sativa L. Sesamum indicum L. Zea mays L. | Nutrition | Solid (bar) | [63] |

| 17. | George, M. | Healthful supplements | Cannabis sativa L. Cocos nucifera L. | Health improvement | Liquid (beverage) and solid (capsules and tablets) | [64] |

| 18. | He, X. | A kind of plant energy rod suitable for sportspeople and preparation method | Helianthus annuus L. | Fatigue delay | Solid (bar) | [65] |

| 19. | Hwang, J.-G. | Composition for increase in muscular functions or exercise capacity comprising Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp., Vicia faba L., or Dolichos lablab L. | Olea europaea L. | Sport performance improvement | Liquid (suspension and syrup), solid (capsules and tablets), and bulk-solid (granules and powder) | [66] |

| 20. | Karaboga, A.S. | Sublingual compositions comprising natural extracts and uses | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. | Joint and muscular pain relief and endurance improvement | Solid (capsules, tablets, and pills), semi-solid (gel, cream, paste, and ointments), and bulk-solid (powder and granules) | [67] |

| 21. | Kawamura, H. | Chewable tablet | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Oenothera biennis L. Oryza sativa L. Persea americana Mill. Sesamum indicum L. | Post-exercise recovery support | Solid (tablets) | [68] |

| 22. | Kim, S.-J. | Composition for muscle strengthening, physical performance improvement, and muscle fatigue recovery | Olea europaea L. | Post-exercise recovery support and sport performance improvement | Solid (capsules, pills, tablets, and chewing gum), semi-solid (cream and gel), and bulk-solid (granules) | [69] |

| 23. | Kleidon, W. | Methods and compositions for enhancing health | Arachis hypogaea L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Sesamum indicum L. Zea mays L. | Health improvement | Liquid (beverage, suspension, and emulsion), semi-liquid (slurry), solid (tablets and capsules), semi-solid (gel), and bulk-solid (powder and granules) | [70] |

| 24. | Komorowski, J.R. | Chromium-containing compositions for improving health and fitness | Arachis hypogaea L. Cocos nucifera L. Olea europaea L. Sesamum indicum L. | Muscle mass increase and muscle strength improvement | Liquid (beverage, elixir, emulsion, and syrup), solid (capsules and tablets), and bulk-solid (powder and granules) | [71] |

| 25. | Konopacki, A. | Prepared foods having high-efficacy omega-6/omega-3-balanced polyunsaturated fatty acids | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Linum usitatissimum L. Vitis vinifera L. Zea mays L. | Nutrition | Liquid (beverage) | [72] |

| 26. | Lauridsen, K.B. | Instant beverage powder based on blg | Brassica napus L. Cocos nucifera L. Helianthus annuus L. | Nutrition | Bulk-solid (powder) | [73] |

| 27. | Laursen, R.R. | Nutraceutical composition for mental activity | Helianthus annuus L. | Mental activity improvement | Semi-solid (gel), bulk-solid (powder), and solid (capsules, pills, cookies, and bars) | [74] |

| 28. | Liu, F. | Protein composition for rapid energy replenishment | Helianthus annuus L. | Nutrition | Solid (bar) | [75] |

| 29. | Longo, V. | A diet composition for enhancing lean body mass and muscle mass | Brassica napus L. Cocos nucifera L. Olea europaea L. | Muscle mass increase | Liquid (soup) | [76] |

| 30. | Maevsky, E.I. | Formulations and dosage forms for enhancing performance or recovery from stress | Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Helianthus annuus L. | Sports performance improvement and post-exercise recovery support | Liquid (syrup and emulsion), solid (capsules, tablets, and lozenges), and bulk-solid (powder) | [77] |

| 31. | Mann, S.J. | Composition comprising a source of nitrate derived from amaranthus leaf and/or rhubarb | Carthamus tinctorius L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Oenothera biennis L. Olea europaea L. | Muscle strength improvement | Solid (capsules, tablets, and lozenges), semi-solid (gel), and bulk-solid (powder and granules) | [78] |

| 32. | Martinez, A. | Methods of reducing exercise-induced injury or enhancing muscle recovery after exercise | Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. | Post-exercise recovery support | Liquid (emulsion, suspension, syrup, and elixir), solid (capsules, tablets, chewing gum, pills, and lozenges), and bulk-solid (granules and powder) | [79] |

| 33. | Mathisen, J.S. | Omega-3 beverage | Nigella sativa L. | Nutrition | Liquid (beverage) | [80] |

| 34. | Miller, P.J. | Compositions and methods for increasing mitochondrial activity | Arachis hypogaea L. Borago officinalis L. Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Cucurbita pepo L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Helianthus annuus L. Juglans regia L. Linum usitatissimum L. Oenothera biennis L. Olea europaea L. Persea americana Mill. Prunus amygdalus Batsch Ribes nigrum L. Sesamum indicum L. | Sports performance improvement | Solid (capsules) and bulk-solid (powder) | [81] |

| 35. | Miura, K. | Composition for improving muscular endurance | Glycine max (L.) Merr. Olea europaea L. Ricinus communis L. Sesamum indicum L. | Endurance improvement | Liquid (suspension), solid (capsules and tablets), semi-solid (gel and cream), and bulk-solid (powder and granules) | [82] |

| 36. | Morita, H. | Composition for improving athletic performance | Glycine max (L.) Merr. Olea europaea L. Zea mays L. | Sports performance improvement | Liquid (suspension and syrup), solid (tablets and capsules), and bulk-solid (powder and granules) | [83] |

| 37. | Morris, S.R. | Formulation for increasing energy | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica oleracea var. italica Plenck Cocos nucifera L. Olea europaea L. Sesamum indicum L. | Cognitive function improvement and endurance improvement | Liquid (suspension and syrup), semi-liquid (slurry), solid (tablets, pills, and capsules), and semi-solid (gel) | [84] |

| 38. | Nielsen, S.B. | pH-neutral beta-lactoglobulin beverage preparation | Brassica napus L. | Nutrition | Liquid (beverage) | [85] |

| 39. | Pang, F. | Sports fermented milk and preparation method | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Linum usitatissimum L. Zea mays L. | Post-exercise recovery support and nutrition | Liquid (beverage) | [86] |

| 40. | Phillips, S. | Multi-nutrient composition | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Juglans regia L. Linum usitatissimum L. Olea europaea L. Zea mays L. | Muscle mass increase, muscle strength improvement, and cognitive function improvement | Liquid (beverage, suspension, and emulsion), semi-solid (gel), solid (bar, tablets, and capsules), and bulk-solid (powder) | [87] |

| 41. | Pradera Bañuelos, D. | Biscuit bar with a moderate sugar content, made with whole grains, nuts, seeds, and extra-virgin olive oil | Olea europaea L. | Nutrition | Solid (bar) | [88] |

| 42. | Rischbieter, I. | High-energy food supplement based on inverted sugars and ergogenic products for use in physical activity and method for producing it | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Cocos nucifera L. Cyrtostachys renda Blume Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Olea europaea L. Zea mays L. | Sports performance improvement | Liquid (beverage) and semi-solid (gel and paste) | [89] |

| 43. | Ryutaro, Y. | Liquid nutritional composition | Arachis hypogaea L. Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Helianthus annuus L. Olea europaea L. Oryza sativa L. Zea mays L. | Post-exercise recovery support and nutrition | Bulk-solid (powder) | [90] |

| 44. | Scheiman, J. | Compositions and methods for enhancing exercise endurance | Arachis hypogaea L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Olea europaea L. Sesamum indicum L. Zea mays L. | Endurance improvement | Solid (pills, tablets, and capsules) | [91] |

| 45. | Sheng, G. | Sports supplement suitable for long-term bodybuilding and preparation method | Carthamus tinctorius L. Cyrtostachys renda Blume Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Olea europaea L. | Muscle mass increase | Bulk-solid (powder) | [92] |

| 46. | Shi, K. | Omega-3 fatty acid-enriched lipidosome exercise drink and preparation method | Linum usitatissimum L. | Post-exercise recovery support | Liquid (beverage) | [93] |

| 47. | Skladtchikova, G.N. | Nutritional compositions | Arachis hypogaea L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Olea europaea L. Zea mays L. | Nutrition | Liquid (beverage, suspension, and syrup) and solid (tablets, capsules, wafers, and chewing gums) | [94] |

| 48. | Steinfeld, U. | Dietary supplements, uses, methods of supplementation, and oral spray | Cocos nucifera L. | Mental and physical stress reduction | Liquid (aqueous solution and emulsion) | [95] |

| 49. | Uberti, F. | Vegetable oil composition and uses | Cannabis sativa L. Linum usitatissimum L. | Health improvement | Solid (tablets, lozenges, and pills) and bulk-solid (granules) | [96] |

| 50. | Van Riet, N. | Food supplement for improving sports performance | Olea europaea L. | Sports performance improvement | Liquid (solution, suspension, and emulsion), solid (capsules and tablets), bulk-solid (powder), and semi-solid (gel) | [97] |

| 51. | Xie, Y. | Composition for promoting health of sportspeople and preparation method | Arachis hypogaea L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Hippophae rhamnoides L. Sesamum indicum L. | Health improvement | Bulk-solid (powder) | [98] |

| 52. | Xu, Q. | High-protein dietary fiber energy protein bar and production method | Cocos nucifera L. Helianthus annuus L. | Post-exercise recovery support | Solid (bar) | [99] |

| 53. | Xu, S. | Double-protein sports milk and preparation method | Brassica napus L. | Post-exercise recovery support, nutrition, and sports performance improvement | Liquid (beverage) | [100] |

| 54. | Yang, J. | A kind of peracidity sports nutrition liquid and its preparation process | Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Helianthus annuus L. Linum usitatissimum L. Oenothera biennis L. Olea europaea L. Zea mays L. | Post-exercise recovery support, muscle strength improvement, and endurance improvement | Liquid (beverage) | [101] |

| 55. | Zhao, Y. | Energy gel with antioxidation function and preparation method | Olea europaea L. | Nutrition | Semi-solid (gel) | [102] |

| 56. | Zhou, Q. | Dual-protein sport supplement and preparation method | Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. | Muscle mass increase | Liquid (tonic) | [103] |

| 57. | Zhou, Q. | A kind of astaxanthin functional sports drink and preparation method | Glycine max (L.) Merr. Linum usitatissimum L. Olea europaea L. | Post-exercise recovery support | Liquid (beverage) | [104] |

| 58. | Zwijsen, R.M.L. | Nutritional compositions for musculoskeletal support for athletes | Brassica napus L. Carthamus tinctorius L. Cocos nucifera L. Glycine max (L.) Merr. Gossypium arboreum L. Helianthus annuus L. Olea europaea L. Zea mays L. | Nutrition | Liquid (beverage) and bulk-solid (powder) | [105] |

References

- Saini, R.K.; Keum, Y.S. Omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Dietary sources, metabolism, and significance—A review. Life Sci. 2018, 203, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Park, K. Omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balić, A.; Vlašić, D.; Žužul, K.; Marinović, B.; Bukvić Mokos, Z. Omega-3 Versus Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuricic, I.; Calder, P.C. Beneficial Outcomes of Omega-6 and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Human Health: An Update for 2021. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, B.; Kapoor, D.; Gautam, S.; Singh, R.; Bhardwaj, S. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs): Uses and potential health benefits. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2021, 10, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.S.; Maki, K.C.; Calder, P.C.; Belury, M.A.; Messina, M.; Kirkpatrick, C.F.; Harris, W.S. Perspective on the health effects of unsaturated fatty acids and commonly consumed plant oils high in unsaturated fat. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 132, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patted, P.G.; Masareddy, R.S.; Patil, A.S.; Kanabargi, R.R.; Bhat, C.T. Omega-3 fatty acids: A comprehensive scientific review of their sources, functions, and health benefits. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariamenatu, A.H.; Abdu, E.M. Overconsumption of Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) versus deficiency of Omega-3 PUFAs in modern-day diets: The disturbing factor for their “balanced antagonistic metabolic functions” in the human body. J. Lipids 2021, 2021, 8848161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhametov, A.; Yerbulekova, M.; Aitkhozhayeva, G.; Tuyakova, G.; Dautkanova, D. Effects of ω-3 fatty acids and ratio of ω-3/ω-6 for health promotion and disease prevention. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e58321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsell, D.; Francis, J.; Ridley, D.; Robards, K. Health promoting constituents in plant derived edible oils. J. Food Lipids 2002, 9, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliszczynska-Swiglo, A.; Sikorska, E.; Khmelinskii, I.; Sikorski, M. Tocopherol content in edible plant oils. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2007, 57, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Šimat, V.; Vlahović, J.; Soldo, B.; Mekinić, I.G.; Čagalj, M.; Hamed, I.; Skroza, D. Production and characterization of crude oils from seafood processing by-products. Food Biosci. 2020, 33, 100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, W.; Lai, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, D. Edible Plant Oil: Global Status, Health Issues, and Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, A.; De Cosmi, V.; Risé, P.; Milani, G.P.; Turolo, S.; Syrén, M.L.; Sala, A.; Agostoni, C. Bioactive compounds in edible oils and their role in oxidative stress and inflammation. Front. Physiol. Phys. 2021, 12, 659551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torres, P.; Puentes, J.G.; Moya, A.J.; La Rubia, M.D. Comparative study of the presence of heavy metals in edible vegetable oils. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.M.M.; Akter, H.; Ali, M.H.; Morshed, A.J.M.; Islam, M.A.; Uddin, M.H.; Uddin Sarkar, M.A.A.S.; Siddik, M.N.A. Physicochemical characterization and determination of trace metals in different edible fats and oils in Bangladesh: Nexus to human health. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawar, M.; Masood, Z.; Ul Hasan, H.; Khan, W.; De los Ríos-Escalante, P.R.; Aldamigh, M.A.; Al-Sowayan, N.S.; Razzaq, W.; Khan, T.; Said, M.B. Trace metals and nutrient analysis of marine fish species from the Gwadar coast. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/2025/us-vegetable-oils-and-fats/?srsltid=AfmBOorpVf1X9YuBO6nUsrHXVzgZ9n76VegG75sgOL4_rnM9Lnc_nUb6 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Sumara, A.; Stachniuk, A.; Montowska, M.; Kotecka-Majchrzak, K.; Grywalska, E.; Mitura, P.; Martinović, L.S.; Kraljević Pavelić, S.; Fornal, E. Comprehensive Review of Seven Plant Seed Oils: Chemical Composition, Nutritional Properties, and Biomedical Functions. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 39, 5402–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Shen, M.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Liang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X. Edible vegetable oils from oil crops: Preparation, refining, authenticity identification and application. Process Biochem. 2023, 124, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallek-Ayadi, S.; Bahloul, N.; Kechaou, N. Chemical composition and bioactive compounds of Cucumis melo L. seeds: Potential source for new trends of plant oils. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 113, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrar, E.; Ahmed, I.A.M.; Manzoor, M.F.; Sarpong, F.; Wei, W.; Wang, X. Gurum seeds: A potential source of edible oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2021, 123, 2000104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Gao, J.; Yi, J.; Liu, P. Could peony seeds oil become a high-quality edible vegetable oil? The nutritional and phytochemistry profiles, extraction, health benefits, safety and value-added-products. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.R.; Liu, Q.; Singh, S. Engineering nutritionally improved edible plant oils. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 14, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, Z. Key components and multiple health functions of avocado oil: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 122, 106494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Bai, J.; Lin, L.; Luo, F.; Zhong, H. A Comprehensive review of health-benefiting components in rapeseed oil. Nutrients 2023, 15, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, P.T.; Ng, C.M.; Ng, Y.T.; Wong, Y.J.; Yap, S.Y.; Leong, S.L.; Yong, S.; Lee, S.W.H. Health Effects of Various Edible Vegetable Oils: An Umbrella Review. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deen, A.; Visvanathan, R.; Wickramarachchi, D.; Marikkar, N.; Nammi, S.; Jayawardana, B.C.; Liyanage, R. Chemical composition and health benefits of coconut oil: An overview. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 2182–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Arellano, D.; Badan-Ribeiro, A.P.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O. Corn oil: Composition, processing, and utilization. In Corn; Serna-Saldivar, S.O., Ed.; AACC International Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2019; pp. 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raole, V.M.; Raole, V.V. Flaxseed and seed oil: Functional food and dietary support for health. EAS J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 4, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Madhagy, S.; Ashmawy, N.S.; Mamdouh, A.; Eldahshan, O.A.; Farag, M.A. A comprehensive review of the health benefits of flaxseed oil in relation to its chemical composition and comparison with other omega-3-rich oils. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Spada, A.; Battezzati, A.; Schiraldi, A.; Aristil, J.; Bertoli, S. Moringa oleifera Seeds and Oil: Characteristics and Uses for Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Przychodzen, P.; Cappello, F.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Knap, N.; Wozniak, M.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Potential Health Benefits of Olive Oil and Plant Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaforio, J.J.; Visioli, F.; Alarcón-de-la-Lastra, C.; Castañer, O.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Fitó, M.; Hernández, A.F.; Huertas, J.R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Menendez, J.A.; et al. Virgin Olive Oil and Health: Summary of the III International Conference on Virgin Olive Oil and Health Consensus Report, JAEN (Spain) 2018. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavahian, M.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Munekata, P.E.; Garcia-Mantrana, I.; Collado, M.C.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Barba, F.J. Health benefits of olive oil and its components: Impacts on gut microbiota antioxidant activities, and prevention of noncommunicable diseases. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finicelli, M.; Squillaro, T.; Galderisi, U.; Peluso, G. Polyphenols, the Healthy Brand of Olive Oil: Insights and Perspectives. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboulbiga, E.B.; Douamba, Z.; Compaoré-Sérémé, D.; Semporé, J.N.; Dabo, R.; Semde, Z.; Tapsoba, F.W.-B.; Hama-Ba, F.; Songré-Ouattara, L.T.; Parkouda, C.; et al. Physicochemical, potential nutritional, antioxidant and health properties of sesame seed oil: A review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1127926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, M.; Shearer, G.; Petersen, K. Soybean oil lowers circulating cholesterol levels and coronary heart disease risk, and has no effect on markers of inflammation and oxidation. Nutrition 2021, 89, 111343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, N.; Maurya, N.K.; Rikhari, A.; Nagar, G. The role of dry fruit oils in athletic performance and health. J. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 6, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, N. Nutritional strategies for optimal endurance and recovery in athletes. J. Front. Multidiscip. Res. 2021, 2, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ficarra, G.; Mannucci, C.; Franco, A.; Bitto, A.; Trimarchi, F.; Di Mauro, D. A case report on dietary needs of the rowing athlete winner of the triple crown. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayech, A.; Mejri, M.A.; Makhlouf, I.; Mathlouthi, A.; Behm, D.G.; Chaouachi, A. Second Wave of COVID-19 Global Pandemic and Athletes’ Confinement: Recommendations to Better Manage and Optimize the Modified Lifestyle. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, J.D.; Witard, O.C.; Galloway, S.D. Applications of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for sport performance. Res. Sports Med. 2019, 27, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; D’Angelo, S. Extra virgin olive oil as a functional food for athletes: Recovery, health, and performance. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2025, 25, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noruzi, A.; Abdekhoda, M. Google Patents: The global patent search engine. Webology 2014, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens, B.; Herrero-Solana, V. Espacenet, Patentscope and Depatisnet: A comparison approach. World Pat. Inf. 2015, 42, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Amyx, L.; Hospelhorn, G.; Choudhury, S. Sports and Nutritional Supplement Formulations. WO2020231906A1, 19 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, L.; Skladtchikova, G.N. Nutritional Compositions for Skeletal Muscle. AU2022287274A1, 21 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Asada, M.; Ito, T.; Miyazaki, A. Sports Drink. JP2016165386A, 26 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barata, M.; Guillemant, M.; Moretti, E.; Müller, E.; Delebarre, M. Nutritional Formulations Comprising a Pea Protein Isolate. EP19186686.2A, 27 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bartos, J.D.; Drummond, E. Endurance Formulation and Use. US20160213673A1, 28 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bermond, G.; Garcon, L. Compositions for the Improvement of Sport Performance. EP21167329.8A, 8 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Billecke, N.; Waschatko, G.; Goossens, E. Nutritional Composition and Process for Preparing It. CN202080092934.6A, 9 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bortz, J.D. Composition for Improved Performance. US15/765,403, 29 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, P.; Schreiber, J. Novel Combinations Comprising Konjac Mannan, Their Compositions and Uses Thereof. WO2024201327A1, 3 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, L.M.; Hawley, J.A.; Moore, D.R.; Stellingwerff, T.; Zaltas, E. Method of Enhancing Muscle Protein Synthesis. AU2016202730A, 28 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Do, P.P.; Harrison, S.-A. Compositon and Method for Nutrition Formulation. US15/595,637, 15 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Liu, Z. Instant Soybean Protein Composition and Preparation Method Thereof. CN201910676127.8A, 25 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dyrvig, M.; Sørensen, S.M.; Greco, B. Neutral Instant Beverage Whey Protein Powder. US18/013,608, 2 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, W.; Carlson, W.B.; Guo, H.W. Compositions for Post-Exercise Recovery and Methods of Making and Using Thereof. CN201780049123.6A, 3 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, C.; Ren, H.; Rudan, B.; Schacht, R.W.; Wang, B. Methods and Compositions Comprising Caffeine and/or a Derivative Thereof and a Polyphenol. CN202280066019.9A, 1 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Franse, M.M.; Jacobs, B.; Scheffelaar, M.H. Protein Bar. EP22801181.3A, 19 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- George, M.; Carrington, B. Healthful Supplements. EP3319446A1, 16 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Xu, Z.; Huang, Y.; He, M.; Cao, J. A Kind of Plant Energy Rod Suitable for Sport People and Preparation Method Thereof. CN201710010393.8A, 6 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.-G.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, D.-E.; Jeong, H.-C.; Kim, H.-M. Composition for Increase of Muscular Functions or Exercise Capacity Comprising Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp., Vicia faba L., or Dolichos lablab L. KR1020190008622A, 23 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karaboga, A.S.; Gegout, S.; Souchet, M. Sublingual Compositions Comprising Natural Extracts and Uses Thereof. EP17710217.5A, 10 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, H.; Kitamura, S.; Takagaki, K. Chewable Tablet. JP2017069855A, 31 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Jeong, M.-G. Composition for Muscle Strengthening, Physical Performance Improvement and Muscle Fatigue Recovery. KR1020200174083A, 14 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kleidon, W. Methods and Compositions for Enhancing Health. WO2018183115A1, 4 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski, J.R. Chromium Containing Compositions for Improving Health and Fitness. GB1814745.4A, 8 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Konopacki, A.; Gurin, M.H. Prepared Foods Having High Efficacy Omega-6/Omega-3 Balanced Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. US202117175457A, 12 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lauridsen, K.B.; Bertelsen, H.; Nielsen, S.B.; De Moura Maciel, G.; Sondergaard, K.; Parjikolaei, B.R.; Jager, T.C. Instant Beverage Powder Based on Blg. PCT/EP2018/067299, 27 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, R.R.; Lange, S.M. Nutraceutical Composition for Mental Activity. EP20845147.6A, 21 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Ke, B. Protein Composition for Rapid Energy Replenishment. CN201910850330.2A, 10 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, V.; Nencioni, A.; Caffa, I. A Diet Composition for Enhancing Lean Body Mass and Muscle Mass. WO2021216839A1, 28 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maevsky, E.I.; Kozhurin, M.V.; Maevskaya, M.E. Formulations and Dosage Forms for Enhancing Performance or Recovery from Stress. US16/763,532, 15 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, S.J. Composition Comprising a Source of Nitrate Derived from Amaranthus Leaf and/or Rhubarb. WO2021198409A1, 7 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, A.; Ferrone, J. Methods of Reducing Exercise-Induced Injury or Enhancing Muscle Recovery After Exercise. AU2021387739A, 22 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen, J.S.; Mathisen, H. Omega-3 Beverage. CA3138995A, 4 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P.J.; Hesse, M. Compositions and Methods for Increasing Mitochondrial Activity. US16/773,333, 27 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, K.; Suzuki, K. Composition for Improving Muscular Endurance. JP2018537427A, 1 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, H.; Kano, T.; Nakamura, T.; Onishi, M. Composition for Improving Athletic Performance. TW202102235A, 16 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, S.R. Formulation for Increasing Energy. US15/398,598, 4 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, S.B.; Jæger, T.C.; Lauridsen, K.B.; Søndergaard, K.; De Moura Maciel, G.; Bertelsen, H.; Parjikolaei, B.R. PH Neutral Beta-Lactoglobulin Beverage Preparation. EP3813549A1, 5 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, F.; Suo, C.; Xue, J.; Yin, X.; Zhang, H. Sports Fermented Milk and Preparation Method Thereof. CN202010400377.1A, 13 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, S.; Parise, G.; Heisz, J. Multi-Nutrient Composition. CA3052324A1, 7 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pradera Bañuelos, D. Biscuit Bar with a Moderate Sugar Content, Made with Whole Grains, Nuts, Seeds and Extra Virgin Olive Oil. ES201700549A, 18 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rischbieter, I.; Biondo, R. High-Energy Food Supplement Based on Inverted Sugars and Ergogenic Products for Use in Physical Activity and Method for Producing Same. BR132020007001A, 8 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ryutaro, Y.; Tomoya, I. Liquid Nutritional Composition. JP2016194378A, 30 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scheiman, J.; Church, G.M.; Kostic, A.D.; Chavkin, T.A.; Luber, J.M. Compositions and Methods for Enhancing Exercise Endurance. US17/432,647, 21 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, G.; Quancheng, Z.; Hui, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Sun, W. Sport Supplement Suitable for Long-Term Bodybuilding and Preparation Method Thereof. CN201810578992.4A, 7 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, K. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Enriched Lipidosome Exercise Drink and Preparation Method Thereof. CN201610938616.2A, 25 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Skladtchikova, G.N.; Andreeva, L. Nutritional Compositions. EP22769330.6A, 24 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld, U.; Holzer, D. Dietary Supplements, Uses Thereof, Methods of Supplementation and Oral Spray. CA3090446A1, 18 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Uberti, F.; Molinari, C.G. Vegetable Oil Composition and Uses Thereof. EP3384780A1, 10 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Riet, N. Food Supplement for Improving Sports Performance. US20220079909A1, 17 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Lu, Z. Composition for Promoting Health of Sports People and Preparation Method Thereof. CN202210571767.4A, 25 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Chen, X.; Liao, L. High-Protein Dietary Fiber Energy Protein Bar and Production Method Thereof. CN201710017677.XA, 10 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Zhou, J.; Deng, W.; Yang, X.; Duan, X.; Li, Q. Double-Protein Sports Milk and Preparation Method Thereof. CN202010456073.7A, 26 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Du, F. A Kind of Peracidity Sport Nutrition Liquid and Its Preparation Process. CN201810261716.5A, 28 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, L.; Ma, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z. Energy Gel with Anti-Oxidation Function and Preparation Method Thereof. CN201711384319.9A, 20 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Sheng, G.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Sun, W.; Wang, S. Dual-Protein Sport Supplement and Preparation Method Thereof. CN201810579253.7A, 7 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q. A Kind of Astaxanthin Functional Sports Drink and Preparation Method Thereof. CN201811357704.9A, 14 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zwijsen, R.M.L.; De Kort, E.J.P.; Versteegen, J.J. Nutritional Compositions for Musculoskeletal Support for Athletes. WO2019158541A1, 22 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Capó, X.; Martorell, M.; Sureda, A.; Riera, J.; Drobnic, F.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Effects of Almond- and Olive Oil-Based Docosahexaenoic- and Vitamin E-Enriched Beverage Dietary Supplementation on Inflammation Associated to Exercise and Age. Nutrients 2016, 8, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capó, X.; Martorell, M.; Busquets-Cortés, C.; Sureda, A.; Riera, J.; Drobnic, F.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Effects of dietary almond-and olive oil-based docosahexaenoic acid-and vitamin E-enriched beverage supplementation on athletic performance and oxidative stress markers. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 4920–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquius, L.; Garcia-Retortillo, S.; Balagué, N.; Hristovski, R.; Javierre, C. Physiological-and performance-related effects of acute olive oil supplementation at moderate exercise intensity. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2019, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquius, L.; Javierre, C.; Llaudó, I.; Rama, I.; Oviedo, G.R.; Massip-Salcedo, M.; Aguilar-Martínez, A.; Niño, O.; Lloberas, N. Impact of Olive Oil Supplement Intake on Dendritic Cell Maturation after Strenuous Physical Exercise: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Calleja-González, J.; Refoyo, I.; León-Guereño, P.; Cordova, A.; Del Coso, J. Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage and Cardiac Stress During a Marathon Could be Associated with Dietary Intake During the Week Before the Race. Nutrients 2020, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieszkowski, J.; Stankiewicz, B.; Kochanowicz, A.; Niespodziński, B.; Kowalik, T.; Żmijewski, M.A.; Kowalski, K.; Rola, R.; Bieńkowski, T.; Antosiewicz, J. Ultra-Marathon-Induced Increase in Serum Levels of Vitamin D Metabolites: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieszkowski, J.; Borkowska, A.; Stankiewicz, B.; Kochanowicz, A.; Niespodziński, B.; Surmiak, M.; Waldziński, T.; Rola, R.; Petr, M.; Antosiewicz, J. Single High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation as an Approach for Reducing Ultramarathon-Induced Inflammation: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayari, D.; Boukazoula, F. Effects of supplementation with virgin olive oil on hormonal status in half-marathon trained and untrained runners. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2023, 23, 23340–23356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, G.d.L.; Batista, J.S.d.F.; Novais, L.M.Q.; Silva, M.B.; Silva Júnior, J.B.d.; Gentil, P.; Marini, A.C.B.; Giglio, B.M.; Pimentel, G.D. Acute Caffeine and Coconut Oil Intake, Isolated or Combined, Does Not Improve Running Times of Recreational Runners: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled and Crossover Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, A.; Hammouda, O.; Turki, M.; Maaloul, R.; Chtourou, M.; Bouaziz, M.; Driss, T.; Souissi, N.; Chamari, K.; Ayadi, F. Moderate walnut consumption improved lipid profile, steroid hormones and inflammation in trained elderly men: A pilot study with a randomized controlled trial. Biol. Sport 2021, 38, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, A.; Nemoto, K.; Sugita, M. Effect of 8-week intake of the n-3 fatty acid-rich perilla oil on the gut function and as a fuel source for female athletes: A randomised trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 129, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, D.C.; Gillitt, N.D.; Meaney, M.P.; Dew, D.A. No Positive Influence of Ingesting Chia Seed Oil on Human Running Performance. Nutrients 2015, 7, 3666–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaga, F.A. The effect of red fruit oil on hematological parameters and endurance performance at the maximal physical activity. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 6, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xu, Z.; Lin, J.; Sun, W.; Xie, Y. Effect of dietary flaxseed oil on the prognosis of acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 7252. [Google Scholar]

- Muros, J.J.; Zabala, M. Differences in Mediterranean Diet Adherence between Cyclists and Triathletes in a Sample of Spanish Athletes. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontele, I.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Vassilakou, T. Level of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Weight Status among Adolescent Female Gymnasts: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2021, 8, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Sánchez, G.; Cruz-Chamorro, I.; Perza-Castillo, J.L.; Vicente-Salar, N. Body Composition Assessment and Mediterranean Diet Adherence in U12 Spanish Male Professional Soccer Players: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, C.; Rocha-Rodrigues, S.; Machado, I.; Lemos, J.; Leal, S.; Nobari, H. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in young male soccer players. BMC Nutr. 2023, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Alcázar, A.E.; García-Roca, J.A.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Its Influence on Anthropometric and Fitness Variables in High-Level Adolescent Athletes. Nutrients 2024, 16, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippou, E.; Middleton, N.; Pistos, C.; Andreou, E.; Petrou, M. The impact of nutrition education on nutrition knowledge and adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in adolescent competitive swimmers. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinovic, D.; Tokic, D.; Martinovic, L.; Kumric, M.; Vilovic, M.; Rusic, D.; Vrdoljak, J.; Males, I.; Ticinovic Kurir, T.; Lupi-Ferandin, S.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Its Association with the Level of Physical Activity in Fitness Center Users: Croatian-Based Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amawi, A.; Alshuwaier, G.; Alaqil, A.; Alkasasbeh, W.J.; Bursais, A.; Al-Nuaim, A.; Alhaji, J.; Alibrahim, M.; Alosaimi, F.; Nemer, L.; et al. Exploring the impact of dietary factors on body composition in elite Saudi soccer players: A focus on added sugars, salt, and oil consumption. Int. J. Hum. Mov. Sports Sci. 2023, 11, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, A.K.; Albassam, R.S. Assessment of General and Sports Nutrition Knowledge, Dietary Habits, and Nutrient Intake of Physical Activity Practitioners and Athletes in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, M.; Frączek, B. Locus of control and dietary habits among junior football players. Pol. J. Sports Med. 2016, 32, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot, M.; Frączek, B.; Tyrała, F. Nutrition Patterns of Polish Esports Players. Nutrients 2023, 15, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.V.; Mirón, I.M.; Vargas, L.A.; Bedoya, J.L. Comparative analysis of adherence to the mediterranean diet among girls and adolescents who perform rhythmic gymnastics. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2019, 25, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muros, J.J.; Knox, E.; Hinojosa-Nogueira, D.; Rufián-Henares, J.Á.; Zabala, M. Profiles for identifying problematic dietary habits in a sample of recreational Spanish cyclists and triathletes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, A.; Martínez-Olcina, M.; Hernández-García, M.; Rubio-Arias, J.Á.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Lara-Cobos, D.; Vicente-Martínez, M.; Carvalho, M.J.; Sánchez-Sáez, J.A. Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Body Composition and Performance in Beach Handball Players: A Cross Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinovic, D.; Tokic, D.; Martinovic, L.; Vilovic, M.; Vrdoljak, J.; Kumric, M.; Bukic, J.; Ticinovic Kurir, T.; Tavra, M.; Bozic, J. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Tendency to Orthorexia Nervosa in Professional Athletes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Barrios, E.M.; Vernetta, M. Body dissatisfaction, Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Anthropometric Data in Female Gymnasts and Adolescents. Apunt. Educ. Fís. Deportes 2022, 149, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, M.P.; Madigan, S.M.; Woodside, J.V.; Nugent, A.P. Dietary Intake, Biological Status, and Barriers towards Omega-3 Intake in Elite Level (Tier 4), Female Athletes: Pilot Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novokshanova, A.L. About the classification of specialized sports nutrition products. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 677, 032054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, P.P.; Rogers, M.B.; Zabinsky, J.S.; Hedrick, V.E.; Rockwell, J.A.; Rimer, E.G.; Kostelnik, S.B.; Hulver, M.V.; Rockwell, M.S. Dietary and biological assessment of the omega-3 status of collegiate athletes: A cross-sectional analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staśkiewicz, W.; Grochowska-Niedworok, E.; Kardas, M.; Polaniak, R.; Grajek, M.; Bialek-Dratwa, A.; Piatek, M. Evaluation of the frequency of consumption of vegetables, fruits and products rich in antioxidants by amateur and professional athletes. Sport Tur. 2022, 5, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura Comes, A.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M.; Domínguez, R. Analysis of Nutritional Supplements Consumption by Squash Players. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrakiewicz-Gierałt, K. Plant-Based Proteins, Peptides and Amino Acids in Food Products Dedicated for Sportspeople—A Narrative Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhakbany, M.A.; Alzamil, H.A.; Alnazzawi, E.; Alhenaki, G.; Alzahrani, R.; Almughaiseeb, A.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Use of Protein Supplements among Saudi Adults: Gender Differences. Healthcare 2022, 10, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.C.; Doyle, L.; Lucey, A. Nutritional priorities, practices and preferences of athletes and active individuals in the context of new product development in the sports nutrition sector. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1088979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitano, M.; Selvaggi, R.; Chinnici, G.; Pappalardo, G.; Yagi, K.; Pecorino, B. Athletes preferences and willingness to pay for innovative high-protein functional foods. Appetite 2024, 203, 107687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Khatun, A.; Liu, L.; Barkla, B.J. Brassicaceae Mustards: Phytochemical Constituents, Pharmacological Effects, and Mechanisms of Action against Human Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gıdık, B.; Önemli, F. Fatty acid compositions and oil ratio of different species from the Brassicaceae. Osman. Korkut Ata Üniversitesi Fen Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2023, 6, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanty, A.; Grudzińska, M.; Paździora, W.; Paśko, P. Erucic Acid—Both Sides of the Story: A Concise Review on Its Beneficial and Toxic Properties. Molecules 2023, 28, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili Tilami, S.; Kouřimská, L. Assessment of the Nutritional Quality of Plant Lipids Using Atherogenicity and Thrombogenicity Indices. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrakiewicz-Gierałt, K. Plant Taxa as Raw Material in Plant-Based Meat Analogues (PBMAs)—A Patent Survey. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista-Production Volume of Olive Oil Worldwide from 2012/13 to 2024/25. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/613466/olive-oil-production-volume-worldwide/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Statista-Production Volume of Soybean Oil Worldwide from 2012/13 to 2024/25. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/620477/soybean-oil-production-volume-worldwide/?srsltid=AfmBOoolKnUZtMpuMy8yijLjog8BaXY6r3kv95P6BBQwJgBJG89Iy6Sc (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Statista. Production Volume of Coconut Oil Worldwide from 2012/13 to 2024/25. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/613147/coconut-oil-production-volume-worldwide/?srsltid=AfmBOorFXUeN8Kt0kIUXM70QrwPz1s_rwikDpzfjLiaSjskdA8DC_BgE (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Statista. Production Volume of Rapeseed Oil Worldwide from 2012/13 to 2024/25. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/613487/rapeseed-oil-production-volume-worldwide/?srsltid=AfmBOopHZcD0OItHW5SbtiGC2f9UZGhUfmlTVsHzSucWzJUmWIWonPd9 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Statista. Production Volume of Sunflowerseed Oil Worldwide from 2012/13 to 2024/25. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/613490/sunflowerseed-oil-production-volume-worldwide/?srsltid=AfmBOoq7N7BOCpcsiHkL_1Gghv_oHe0zbKFWP-D9uXXLk4mFrTXsRhxr (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Statista. Production Volume of Peanut Oil Worldwide from 2012/13 to 2024/25. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/613483/peanut-oil-production-volume-worldwide/?srsltid=AfmBOoqB6YS-YdS9wejSoIuvw8COmdgMZqJbdiY3Bneq1i9fx7Lxuy3_ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Akmeemana, C.; Dulani Somendrika, M.A.; Abeysundara, P.D.A. Underutilized plant oil sources: Fatty acid composition, physicochemical properties, applications, and health benefits. In Biology of Fatty Acids; Meran Keshawa, E.P., Cho, S.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2026; pp. 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, H.; Sharma, S.; Bala, M. Technologies for extraction of oil from oilseeds and other plant sources in retrospect and prospects: A review. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 44, e13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xin, Q.; Yuan, R.; Miao, Y.; Yang, M.; Mo, H.; Chen, K.; Cong, W. Protective effects of oleic acid and polyphenols in extra virgin olive oil on cardiovascular diseases. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, R.; Infante, M.; Pastore, D.; Pacifici, F.; Chiereghin, F.; Malatesta, G.; Donadel, G.; Tesauro, M.; Della-Morte, D. An Appraisal of the Oleocanthal-Rich Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) and Its Potential Anticancer and Neuroprotective Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrero, A.D.; Ortega-Vidal, J.; Salido, S.; Castilla, L.; Vidal, I.; Quesada, A.R.; Altarejos, J.; Martínez-Poveda, B.; Medina, M.A. Anti-angiogenic effects of oleacein and oleocanthal: New bioactivities of compounds from Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera-Navarro, C.; Montoro-García, S.; Orenes-Pinero, E. Hydroxytyrosol: Its role in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumuzachi, O.; Kieserling, H.; Rohn, S.; Mocan, A. The impact of oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and tyrosol on cardiometabolic risk factors: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 6898–6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Gad, M.Z. Omega-9 fatty acids: Potential roles in inflammation and cancer management. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirrou, I.; El Harrak, A.; El Antari, A.; Hssaini, L.; Hanine, H.; El Fechtali, M.; Nabloussi, A. Bioactive Compounds Assessment in Six Moroccan Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) Varieties Grown in Two Contrasting Environments. Agronomy 2023, 13, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.; Madonna, G.; Di Palma, D. Effects of fish oil supplementation in the sport performance. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 2322–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N.A.; Daniels, D.; Calder, P.C.; Castell, L.M.; Pedlar, C.R. Are there benefits from the use of fish oil supplements in athletes? A systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 1300–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielecke, F.; Blannin, A. Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Sport Performance—Are They Equally Beneficial for Athletes and Amateurs? A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, K.A.; Zello, G.A.; Bandy, B.; Ko, J.; Bertrand, L.; Chilibeck, P.D. Dietary Supplementation for Para-Athletes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mburu, M. The Role of Chia Seeds Oil in Human Health: A Critical Review. Eur. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2021, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakantan, N.; Seah, J.Y.H.; van Dam, R.M. The effect of coconut oil consumption on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Circulation 2020, 141, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newport, M.T.; Dayrit, F.M. Analysis of 26 Studies of the Impact of Coconut Oil on Lipid Parameters: Beyond Total and LDL Cholesterol. Nutrients 2025, 17, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forelli, F.; Moiroux-Sahraoui, A.; Nielsen-Le Roux, M.; Miraglia, N.; Gaspar, M.; Stergiou, M.; Bjerregaard, A.; Mazeas, J.; Douryang, M., Sr. Stay in the Game: Comprehensive Approaches to Decrease the Risk of Sports Injuries. Cureus 2024, 16, e76461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Chen, A.Q.; Huang, J.; Wang, M.; Luo, J.H.; Wang, A.; Wang, X.Y. Edible plant oils modulate gut microbiota during their health-promoting effects: A review. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1473648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Caselles, L. Promotion of Extra Virgin Olive Oil as an ergogenic aid for athletes. Arch. Med. Deporte 2024, 41, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, E.; Erbasan, H.; Riso, P.; Perna, S. Impact of the Mediterranean Diet on Athletic Performance, Muscle Strength, Body Composition, and Antioxidant Markers in Both Athletes and Non-Professional Athletes: A Systematic Review of Intervention Trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, A.; Matu, J.; Whyte, E.; Akin-Nibosun, P.; Clifford, T.; Stevenson, E.; Shannon, O.M. The Mediterranean dietary pattern for optimising health and performance in competitive athletes: A narrative review. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massart, A.; Rocha, Á.; Ferreira, J.P.; Soares, C.; Campos, M.J.; Martinho, D. Why Is the Association Between Mediterranean Diet and Physical Performance in Athletes Inconclusive? Implications for Future Studies. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Bai, Y.; Tian, H.; Zhao, X. The Chemical Composition and Health-Promoting Benefits of Vegetable Oils—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.R.; Sygo, J.; Morton, J.P. Fuelling the female athlete: Carbohydrate and protein recommendations. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2022, 22, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhiman, C.; Kapri, B.C. Optimizing Athletic Performance and Post-Exercise Recovery: The Significance of Carbohydrates and Nutrition. Monten. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2023, 12, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illahi, R.R.; Rasyid, W.; Neldi, H.; Padli, P.; Ockta, Y.; Cahyani, F.I. The Crucial Role of Carbohydrate Intake for Female Long-Distance Runners: A Literature Review. J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA 2023, 9, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witard, O.C.; Hearris, M.; Morgan, P.T. Protein nutrition for endurance athletes: A metabolic focus on promoting recovery and training adaptation. Sports Med. 2015, 55, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, S.P.; Nienhuis, M.; Biagioli, B.; De Pauw, K.; Meeusen, R. Supplementation Strategies for Strength and Power Athletes: Carbohydrate, Protein, and Amino Acid Ingestion. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, L.C. Edible seeds and nuts in human diet for immunity development. Int. J. Recent. Sci. Res. 2020, 6, 38877–38881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, A.; Singh, N. Seeds as nutraceuticals, their therapeutic potential and their role in improving sports performance. J. Phytol. Res. 2021, 34, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Baroni, L.; Pelosi, E.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. The VegPlate for Sports: A Plant-Based Food Guide for Athletes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, F.; Rossi, E.V.; Arrieta, E.M. Nutritional considerations for vegetarian athletes: A narrative review. Hum Nutr Metab. 2024, 37, 200267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, C.; Bank, N.; Cook, B.; Mistovich, R.J. Nutritional recommendations for the young athlete. J. Pediatr. Orthop. Soc. N. Am. 2023, 5, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prarthana, J.; Nischitha, N.; Shraddha, S.; Ramu, R. Effect of repeated heating on chemical properties of selected edible plant oil and its health hazards. Int. J. Health Allied Sci. 2023, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, X.F. Lipid oxidation products on inflammation-mediated hypertension and atherosclerosis: A mini review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 717740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Family | Taxon | Number of Patents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin Name | Selected Common Name (s) | ||

| Anacardiaceae | Anacardium occidentale L. | Cashew nut | 1 |

| Apiaceae | Coriandrum sativum L. | Coriander | 1 |

| Arecaceae | Cyrtostachys renda Blume | Sealing wax palm | 2 |

| Cocos nucifera L | Coconut | 29 | |

| Asteraceae | Carthamus tinctorius L. | Safflower | 18 |

| Helianthus annuus L. | Sunflower | 24 | |

| Betulaceae | Corylus avellana L. | Hazelnut | 1 |

| Boraginaceae | Borago officinalis L. | Borage | 2 |

| Brassicaceae | Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. | Brown mustard | 1 |

| Brassica napus L. | Rapeseed; canola | 26 | |

| Brassica oleracea var. italica Plenck | Broccoli | 1 | |

| Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz | Camelina; false flax | 1 | |

| Sinapis alba L. | White mustard | 1 | |

| Cannabaceae | Cannabis sativa L. | Hemp | 3 |

| Cucurbitaceae | Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai | Bitter apple; bitter melon | 1 |

| Cucurbita pepo L. | Pumpkin | 1 | |

| Elaeagnaceae | Hippophae rhamnoides L. | Sea buckthorn | 1 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Ricinus communis L. | Castor oil plant | 2 |

| Fabaceae | Arachis hypogaea L. | Peanut; groundnut | 22 |

| Glycine max (L.) Merr. | Soybean; soya | 32 | |

| Fagaceae | Fagus sylvatica L | Common beech | 1 |

| Grossulariaceae | Ribes nigrum L. | Black currant; blackcurrant | 3 |

| Juglandaceae | Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) K.Koch | Pecan | 1 |

| Juglans major (Torr.) A. Heller | Arizona walnut | 1 | |

| Juglans regia L. | Common walnut | 4 | |

| Lamiaceae | Salvia hispanica L. | Chia | 1 |

| Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill. | Avocado | 4 |

| Lecythidaceae | Bertholletia excelsa Humb. & Bonpl. | Brazil nut | 1 |

| Linaceae | Linum usitatissimum L. | Flax; flaxseed; common flax | 13 |

| Malvaceae | Gossypium arboreum L. | Cotton; tree cotton | 11 |

| Oleaceae | Olea europaea L. | Olive | 33 |

| Onagraceae | Oenothera biennis L. | Evening primrose | 5 |

| Pedaliaceae | Sesamum indicum L. | Sesame | 14 |

| Poaceae | Oryza sativa L. | Rice | 4 |

| Triticum aestivum L. | Common wheat | 1 | |

| Zea mays L. | Maize; corn | 21 | |

| Ranunculaceae | Nigella sativa L. | Black cumin | 1 |

| Rosaceae | Prunus amygdalus Batsch | Almond | 4 |

| Vitaceae | Vitis vinifera L. | Common grape | 4 |

| Author(s) and Year of Publication | Country | Sports Discipline Sex; Age (Mean ± SD or Years); Number of Participants | Treatment | Duration | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayari and Boukazoula (2023) [113] | Not specified | Half-marathon M; 19–22; 30 | Group 1: untrained runners receiving 20 mL/day of virgin olive oil (control); Group 2: half-marathon runners performing training routines 5 days a week, receiving 20 mL/day of olive oil; Group 3: half-marathon runners performing training routines 5 days a week and unsupplemented with virgin olive oil. | 10 weeks | Changes among test groups Similar levels of T, LH, FSH, CORT, and insulin at baseline; The greatest level of T and LH in Group 2, as well as CORT in Group 3, before and immediately after a marathon race, as well as 24 h after a race. Changes from baseline ↔ Level of insulin and FSH in all groups; ↑ T level in Group 2 and ↑ CORT in Group 3. |

| Borba et al. (2019) [114] | Brazil | Recreational run -; 28.46 ± 5.63; 13 | Consumption of (1) Placebo water (control); (2) Decaffeinated coffee plus isolated caffeine (test group); (3) Decaffeinated coffee plus isolated caffeine plus soy oil (test group); (4) Decaffeinated coffee plus isolated caffeine plus extra-virgin coconut oil (test group). The substances were ingested 60 min before a 1600 m time trial at a 400 m track. | 4 sessions separated by one-week intervals | After supplementation In all groups, ↔ RPE and running time. Changes from baseline In all groups, ↔ Blood lactate concentration. |

| Capó et al. (2016) [106] | Spain | Taekwondo M; 22.8 ± 3.8; 5 (young sportspeople) Athletics M; 45.6 ± 1.6; 5 (senior sportspeople) | Consumption of 1 L of almond beverage containing olive oil five days a week. Half of the beverage was taken in the morning, and the other half before the daily training session. The results obtained after the nutritional intervention (supplemented groups) were compared with those obtained at the beginning of the intervention (control groups). | 5 weeks | After supplementation ↑ TNFα and ↑ 15LOX2 gene expression and IL1β; ↔ IL10, IL15, HSP72, NFκβ, and TLR4. After exercise ↑ DHA in erythrocytes; ↑ TNFα gene expression in PBMCs in young sportspeople; ↑ 15LOX2 gene expression, especially in the senior group; ↔ Expression of TLR4, NFκβ, 5LOX, IL-10, IL-15, and HSP72 in PBMCs; ↑ Plasma NFEAs, sICAM3, and sL-selectin; ↓ LX in the senior group. |

| Capó et al. (2016b) [107] | Spain | Taekwondo M; 22.8 ± 3.8; 5 (young sportspeople) Athletics M; 45.6 ± 1.6; 5 (senior sportspeople) | Consumption of 1 L of almond beverage containing olive oil five days a week. Half of the beverage was taken in the morning, and the other half before the daily training session. The results obtained after the nutritional intervention (supplemented groups) were compared with those obtained at the beginning of the intervention (control groups). | 5 weeks | After supplementation ↑ PUFA, ↑ DHA erythrocyte content, and ↓ SFA; ↔ blood polyphenol levels; ↑ RBC concentration in senior athletes; ↓ Plasma MDA concentration; ↑ Hemoglobin (Hb) (g per 100 mL) in the senior group. After exercise ↔ HCT (%), NOx plasma levels, nitrite (nM), LPO, CI, SFA, and PUFA in all groups; ↑ Hb in all groups; ↓ Blood polyphenols and RBCs in all groups; ↑ CI in the senior groups; ↑ MUFA in the young groups. |

| Esquius et al. (2019) [108] | Spain | Running M; 22.2 ± 4.3; 7 | Dietary supplementations in a randomized order: (i) 25 mL of extra-virgin olive oil, (ii) 25 mL of palm oil, (iii) and 8 g of a placebo. | Three effort sessions separated by 7-day intervals | Changes from baseline ↑ Ventilation efficiency and cardiorespiratory system in olive oil supplementation compared with palm oil; ↔ Moderate exercise intensity with palm oil and placebo supplementation; ↔ High exercise intensity with supplementation; ↔ Exercise time with supplementation. |

| Esquius et al. (2021) [109] | Spain | Recreational sports training M; 35–51; 3 | Dietary supplementations: (i) active supplement (100 mL of commercial orange juice, 8 g of modified starch, and 25 mL of extra-virgin olive oil); (ii) placebo (100 mL of commercial orange juice and 8 g of modified starch). | Twice, separated by 7-day interval | Changes from baseline ↓ DC (markers of inflammatory process) after active supplement intake. |

| Kamoun et al. (2021) [115] | Tunisia | Recreational strength and endurance training M; 66.5 ± 2.68; 10 (test group) M; 66.9 ± 2.13; 10 (control) | Test group: concurrent training + dietary walnut consumption (15 g/day). Control: concurrent training + control diet. | 6 weeks | Test group vs. control group In the test group, ↓ TC, LDL, and TG; ↓ CRP; ↑ HDL. |

| Kawamura et al. (2023) [116] | Japan | Volleyball F; 20.2 ± 1.3; 36 12 athletes (test group 1) 12 athletes (test group 2) 12 athletes (control) | Test group 1: 9 g/day of perilla oil. Test group 2: 3 g/day of perilla oil. Control: placebo. | 8 week | Test group vs. control group In test group 1, ↓ Urinary IS; ↓ Spoilage bacteria (Proteobacteria); ↑ Butyrate-producing bacteria (Lachnospiraceae). |

| Mielgo-Ayuso et al. (2020) [110] | Spain | Marathon race M; 44.94 ± 8.77; 69 | 2–4 servings of olive oil per day, 7 days before the race. | One week | Changes from baseline ↓ TNI and TNT post-marathon concentration as markers of EIMD and EICS, respectively. |

| Mieszkowski et al. (2020) [111] | Poland | Ultramarathon race M; 42.00 ± 8.44; 13 (test group) M; 40.00 ± 8.11; 14 (control) | Test group: a single dose (150,000 IU) of vitamin D, as a solution in 10 mL of vegetable oil, 24 h before starting the race. Control: placebo. | One day | Test group vs. control group ↑ Serum 25(OH)D3, 24,25(OH)2D3, and 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels significantly after supplementation. Changes from baseline ↑ Serum 25(OH)D3, 24,25(OH)2D3, and 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels significantly after the ultramarathon in test and control groups. |

| Mieszkowski et al. (2021) [112] | Poland | Ultramarathon race M; 42.40 ± 7.59; 16 (test group) M; 39.48 ± 6.89; 19 (control) | Test group: a single dose (150,000 IU) of vitamin D, as a solution in 10 mL of vegetable oil, 24 h before starting the race. Control: placebo. | One day | Test group vs. control group ↑ Serum 25(OH)D in the test group. Changes from baseline ↑ IL 6 and 10 IL-6; ↑ IL10 and resistin levels immediately after the run, especially in the control group; ↓ Leptin, ↓ OSM, and ↓ TIMP levels. |

| Nieman et al. (2015) [117] | USA | Running M; 24–55; 16 F; 24–55; 8 | Test group: 0.5 L of water with chia seed oil (0.43 g of ALA/BM) + run. Control group: 0.5 L of water + run. | Twice separated by two weeks | Test group vs. control group In the test group, post-run, ↑ Plasma ALA; ↔ RER and run time to exhaustion, ↔ oxygen consumption, ↔ ventilation, and ↔ blood lactate. Changes from baseline ↑ Leukocyte number, ↑ plasma ALA, ↑ cortisol (CORT), and ↑ IL-6; ↑ IL8, ↑ IL10, and ↑ TNF-α. |

| Sinaga (2017) [118] | Not specified | Athletics -; 20–23; 15 (test group) -; 20–23; 15 (control group) | Test group: consumption of red fruit oils once a day after meal. | 3 months | Test group vs. control group ↑ VO2max, ↑ number of erythrocytes, and ↑ levels of Hb and HCT in the test group. |

| Tang et al. (2022) [119] | China | Ball sports, running, climbing, dancing, swimming, and fitness M; 15–44; 50 (test group) F; 15–44; 21 (test group) M; 15–45; 47 (control) F; 15–45; 24 (control) | Test group: 6 flaxseed oil capsules daily. Control: 6 corn oil capsules daily. | 2 years | Test group vs. control group ↑ IKDC and KOOS scores after two-year administration in test group. |

| Author(s) and Year of Publication | Risk of Bias Domains | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | Overall | |

| Ayari and Boukazoula (2023) [113] | ? | L | L | L | L | SC |

| Borba et al. (2019) [114] | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Capó et al. (2016) [106] | ? | L | L | L | L | SC |

| Capó et al. (2016b) [107] | ? | L | L | L | L | SC |

| Esquius et al. (2019) [108] | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Esquius et al. (2021) [109] | L | L | ? | L | L | SC |

| Kamoun et al. (2021) [115] | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Kawamura et al. (2023) [116] | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Mielgo-Ayuso et al. (2020) [110] | ? | L | ? | L | L | SC |

| Mieszkowski et al. (2020) [111] | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Mieszkowski et al. (2021) [112] | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Nieman et al. (2015) [117] | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Sinaga (2017) [118] | ? | L | L | ? | L | SC |

| Tang et al. (2022) [119] | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Author(s) and Year of Publication | Country | Sports Discipline | Sex; Age (Mean ± SD or Range of Years); Number of Participants | Plant Oil | Use of Plant Oils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amawi et al. (2023) [127] | Saudi Arabia | Soccer | M; 19 ±1; 81 | Olive oil | 40 (49.4%) respondents declared consumption of olive oil |

| Alahmadi, Albassam (2023) [128] | Saudi Arabia | Athletics | M,F; 26.41 ± 8.1; 261 | Olive oil | 46.1% of respondents confirmed use of olive oil for cooking or baking |

| Gacek and Frączek (2016) [129] | Poland | Football | M; 17–19; 303 | Olive oil and other plant oils | Olive oil is consumed less frequently than other plant oils |

| Hooks et al. (2023) [136] | Ireland | Hockey; cricket | F; 24.8 ± 4.5; 35 | Canola oil; flaxseed oil | 20 athletes consume canola oil, while 2 respondents consume flaxseed oil |

| Kontele et al. (2021) [121] | Greece | Gymnastics | F; 11–18; 319 | Olive oil | 93.3% of participants reported using olive oil at home |

| Leão et al. (2023) [123] | Portugal | Soccer | M; 12.0 ± 2.2; 132 | Olive oil | 131 (99%) of respondents declared the use of olive oil at home |

| Martínez–Rodríguez et al. (2021) [133] | Spain | Handball | M; 17.0 ± 0.1; 14 (junior) M; 25.5 ± 4.7; 24 (senior) F; 16.1 ± 1.46; 7 (junior) F; 23.2 ± 2.9; 14 (senior) | Olive oil | The use of olive oil at home was confirmed by 7 (33%) junior females, 14 (68%) senior females, 13 (34%) junior males, and 23 (60%) senior males |

| Martinovic et al. (2021) [126] | Croatia | Fitness | F; 30.3 ± 9.9; 530 M; 28.2 ± 7.8; 690 | Olive oil | The use of olive oil was confirmed by 34% of the participants |

| Martinovic et al. (2022) [134] | Croatia | Athletics | M; 24.5 ± 4.0; 87 (professional athletes) F; –; 63 (professional athletes) M; 24.0 ± 5.5; 78 (recreational athletes) F; –; 72 | Olive oil | The use of olive oils was confirmed by 52 (34.7%) professional athletes and 21 (14.0%) recreational athletes |

| Muros and Zabala (2018) [120] | Spain | Cycling; triathlon | F,M; 34.14 ± 9.28; 4037 | Olive oil | 95% of the participants use olive oil as the principal source of fat for cooking 4 or more tablespoons of olive oil per day is consumed by 78.5% of the participants from southern Spain and 74.1% of the participants from northern Spain |

| Muros et al. (2021) [132] | Spain | Cycling; triathlon | F,M; 34.14 ± 9.28; 4037 | Olive oil | The number of servings of olive oil per day reaches 1.36 ± 1.16 among males, 1.88 ± 1.62 among females, 1.47 ± 1.25 among triathletes, and 1.35 ± 1.20 among cyclists |

| Novokshanova (2021) [137] | Russia | Athletics | F,M; –; 1267 | Vegetable oils | 215 (17%) of the respondents use vegetable oils as a source of fat |

| Peláez–Barrios, Vernetta (2022) [135] | Spain | Acrobatic gymnastics | F; 13.69 ± 3.05; 81 (gymnasts) F; 14.04 ± 1.49; 70 (non-gymnasts) | Olive oil | The use of olive oil was reported by 80 (98.8%) gymnasts and 51 (72.9%) non-gymnasts |

| Philippou et al. (2017) [125] | Cyprus | Swimming | F; –; 11 M; –; 23 | Olive oil | 71% of respondents used olive oil before the nutrition education workshop 82% of respondents used olive oil after the nutrition education workshop |

| Ritz et al. (2020) [138] | USA | Baseball, basketball, cross country, football, golf, gymnastics, soccer, softball, swimming and diving, track and field, and volleyball | F,M; >18 years; 1562 | Canola oil | Canola oil is consumed by 85% of the participants, while flax oil or flax is consumed by 34.9% of the participants |

| Santana et al. (2019) [131] | Spain | Rhythmic gymnastics | F; 7–12; 124 (younger) F; 13–17; 97 (adolescents) | Olive oil | 94.4% of younger and 88.7% of adolescent gymnasts declared use of olive oil |

| Santos-Sánchez et al. (2021) [122] | Spain | Soccer | M; 8–12; 75 | Olive oil | 100% of respondents declared the use of olive oil at home |

| Staśkiewicz e al. (2022) [139] | Poland | Bodybuilding, CrossFit, football, and handball | M; 23.90 ± 4.08; 30 (professional football players) M; 24.37 ± 4.15; 30 (professional handball players) M; 25.00 ± 4.00; 33 (amateur bodybuilding sportspeople) M; 24.30 ± 3.78; 26 (amateur CrossFit sportspeople) | Vegetable oils | Frequency of participants who used 1 tablespoon of oils reached 3.70 ± 1.44 in the case of the amateur players and 3.33 ± 1.17 in the case of the professional players Frequency of participants who used 1 tablespoon of oils ranged from 3.30 ± 0.54 (handball players) to 3.37 ± 0.46 (football players), 3.54 ± 0.37 (CrossFit), and 3.54 ± 0.37 (bodybuilders) |

| Szot et al. (2023) [130] | Poland | Esport | M; 20.5 ± 2.0; 233 | Canola oil; coconut oil; olive oil | 43.35% of the respondents consume olive oil and canola oil 1–3 times per month, 18.03% of the respondents consume them once a day, and 0.43% consume them 4–5 times a day; the mean frequency of consumption of coconut oil reaches 2.17 ± 1.42 servings |

| Ventura Comes et al. (2018) [140] | Spain | Squash | M; –; 10 (international players) F; –; 4 (international players) M; –; 20 (national players) F; –; 8 (national players) | Coconut oil; flaxseed oil | Flaxseed oil is consumed by 4 (28.6%) international players and 1 (3.6%) national player. Coconut oil is consumed by 3 (21.4%) international players and 2 (7.1%) national players |

| Vélez-Alcázar et al. (2024) [124] | Spain | Athletics | M; 18.31 ± 2.31; 47 F; 17.27 ± 1.44; 49 | Olive oil | The use of olive oil at home is declared by 57 (96.6%) of respondents with excellent, 29 (96.7%) with moderate, and 5 (71.4%) with poor adherence to the Mediterranean diet |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kostrakiewicz-Gierałt, K. Plant Oils in Sport Nutrition: A Narrative Literature Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3943. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243943

Kostrakiewicz-Gierałt K. Plant Oils in Sport Nutrition: A Narrative Literature Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3943. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243943

Chicago/Turabian StyleKostrakiewicz-Gierałt, Kinga. 2025. "Plant Oils in Sport Nutrition: A Narrative Literature Review" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3943. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243943

APA StyleKostrakiewicz-Gierałt, K. (2025). Plant Oils in Sport Nutrition: A Narrative Literature Review. Nutrients, 17(24), 3943. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243943