Virtual Reality Trier Social Stress and Virtual Supermarket Exposure: Electrocardiogram Correlates of Food Craving and Eating Traits in Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Preparatory Phase—Consent and Baseline Questionnaires

2.2.2. Pre-Exposure Stage (T-13 min to T0 min)

2.2.3. VR-TSST Stage (T0 min to T + 10 min)—Speech and Arithmetic Tasks

2.2.4. Post VR-TSST (T + 10 min to T + 15 min)—ECG and VAS

2.2.5. Virtual Supermarket (T + 15 min to T + 25)

2.2.6. Post-Exposure Phase (T + 25 to T + 35)—VR Exposure Questionnaire, Anthropometrics (BMI, Waist Circumference, Height)

2.3. Virtual Reality (VR) Environments

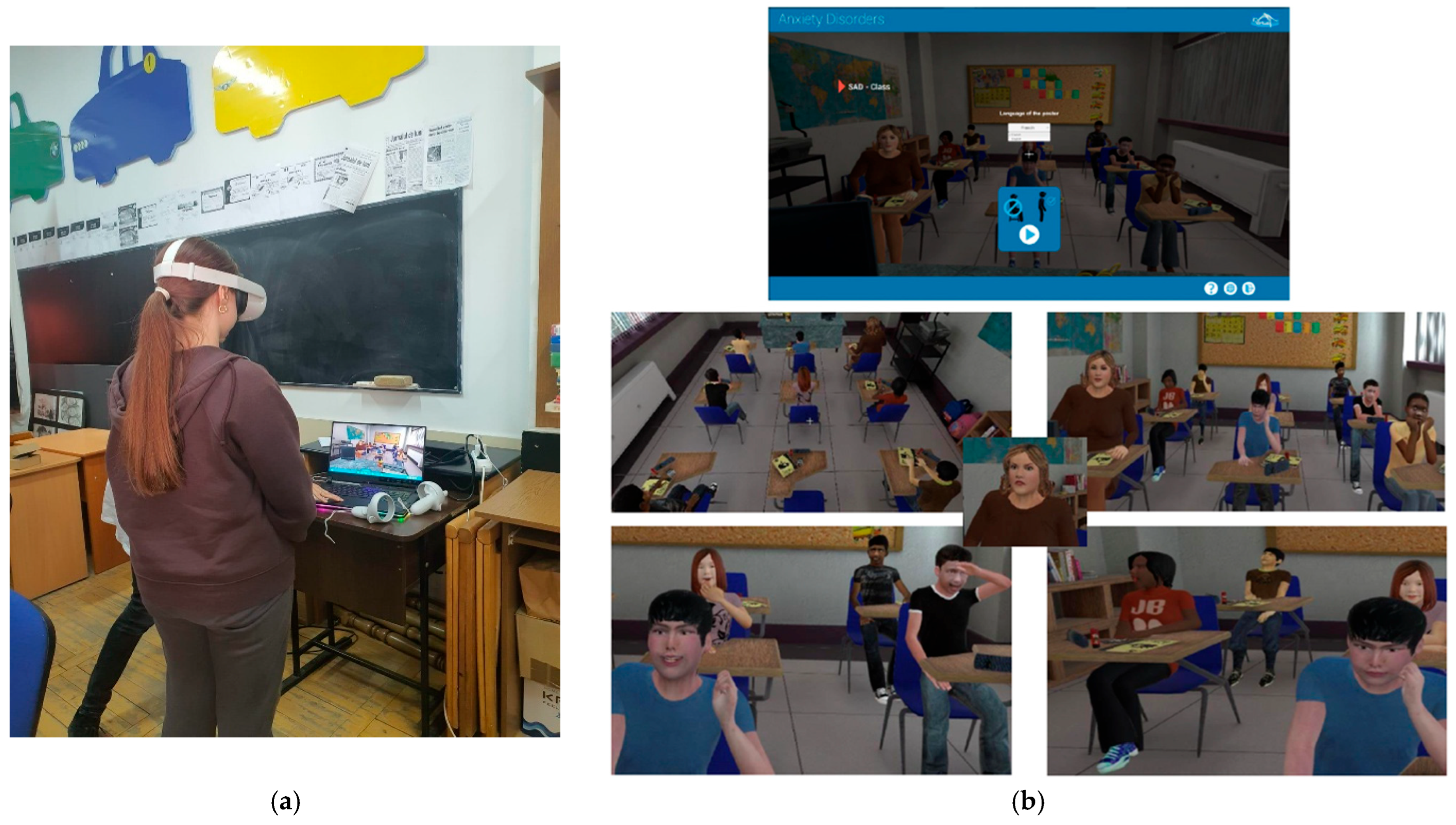

2.3.1. Virtual Classroom

2.3.2. Virtual Supermarket

2.4. Electrocardiogram (ECG) Monitoring

2.5. Psychological Measurements

2.5.1. Stress and Anxiety Assessment

Pre-TSST Exposure

Post-TSST Exposure

- -

- Stress and Anxiety Assessment (VAS Method)

- -

- Virtual Supermarket Exposure

- -

- Immersion Presence Questionnaire

2.6. Anthropometric Measurements

Sample Size and Power Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Autonomic Nervous System Responses to VR TSST

4. Discussions

4.1. Relationship Between Eating Traits (UE, EE, CR) and Post-Stress Cravings

4.2. Relationship Between Physiological Changes and Post-Stress Cravings

4.3. Virtual TSST and Food Exposure

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Do, S.; Didelez, V.; Börnhorst, C.; Coumans, J.M.; Reisch, L.A.; Danner, U.N.; Russo, P.; Veidebaum, T.; Tornaritis, M.; Molnár, D.; et al. The role of psychosocial well-being and emo-tion-driven impulsiveness in food choices of European adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Cena, H.; Rossi, V.; Santero, S.; Bianchi, A.; Zuccotti, G. Ultra-Processed Food, Reward System and Childhood Obesity. Children 2023, 10, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, O.R.; Lim, S.-L. The role of emotion in eating behavior and decisions. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1265074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich-Lai, Y.M.; Fulton, S.; Wilson, M.; Petrovich, G.; Rinaman, L. Stress exposure, food intake and emotional state. Stress 2015, 18, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klatzkin, R.R.; Nolan, L.J.; Kissileff, H.R. Self-reported emotional eaters consume more food under stress if they experience heightened stress reactivity and emotional relief from stress upon eating. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 243, 113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.P.; DeJesus-Rodriguez, A.; Rihal, T.K.; Raposa, E.B. Associations between trait food craving and adolescents’ prefer-ences for and consumption of healthy versus unhealthy foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 108, 104887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ye, N.; Xu, X. Perceived Stress and Emotional Eating in Adolescence: Mediation Through Negative-Focused Cognitive Emotion Regulation and Reward Sensitivity. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatwan, I.M.; Alzharani, M.A. Association between perceived stress, emotional eating, and adherence to healthy eating pat-terns among Saudi college students: A cross-sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvaez Linares, N.N.; Charron, V.; Ouimet, A.J.; Labelle, P.R.; Plamondon, H. A systematic review of the Trier Social Stress Test methodology: Issues in promoting study comparison and replicable research. Neurobiol. Stress 2020, 13, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, A.; Jarvers, I.; Kocur, M.; Kandsperger, S.; Brunner, R.; Schleicher, D. Multifactorial stress reactivity to virtual TSST-C in healthy children and adolescents-It works, but not as well as a real TSST-C. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2024, 160, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, G.S.; Strahm, A.M.; Bagne, A.G.; Hilmert, C.J. Using virtual reality to study the impact of audience size on cor-tisol responses to the Trier Social Stress Test. Int. J. Virtual Real. 2023, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onita, C.A.; Matei, D.-V.; Trandafir, L.-M.; Petrescu-Miron, D.; Corciova, C.; Fuior, R.; Manole, L.-M.; Mihai, B.-M.; Dascalu, C.-G.; Tarcea, M.; et al. Autonomic and Neuroendocrine Reactivity to VR Game Exposure in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Factor Analytic Approach to Physiological Reactivity and Eating Behavior. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnant, K.; Klosowska, J.; Braet, C.; Verbeken, S.; De Henauw, S.; Vanhaecke, L.; Michels, N. Stress Responsiveness and Emotional Eating Depend on Youngsters’ Chronic Stress Level and Overweight. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotca, I.; Druica, A.; Timofte, D.V.; Preda, C.; Ghiciuc, C.M.; Ungureanu, M.C.; Leustean, L.; Mocanu, V. Cortisol Reactivity to a Digital Version of Trier Social Stress Test and Eating Behavior in Non-Overweight and Overweight Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 9683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onita, C.A.; Matei, D.; Onu, I.; Iordan, D.; Chelarasu, E.; Tupita, N.; Petrescu-Miron, D.; Radeanu, M.; Juravle, G.; Corciova, C.; et al. Using VR Supermarket for Nutritional Research and Education: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2024, 17, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cliniques et Développement IN VIRTUO. Operating Manual for In Virtuo’s Virtual Environments, 3rd ed.; Cliniques et Développement IN VIRTUO: Gatineau, QC, Canada. Available online: https://invirtuo.com/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Chelarasu, E. Monitorizarea Dependenţei Nutriţionale Utilizând Medii Virtuale. Ph.D. Thesis, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tuboly, G.; Kozmann, G.; Kiss, O.; Merkely, B. Atrial fibrillation detection with and without atrial activity analysis using lead-I mobile ECG technology. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2021, 66, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIWE. WIWE Device. Available online: https://www.mywiwe.com/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Phoon, C.K. Mathematic validation of a shorthand rule for calculating QTc. Am. J. Cardiol. 1998, 82, 400–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D.F. The normal ECG in childhood and adolescence. Heart 2005, 91, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, W. Effects of gender, age, and heart rate on QT intervals in children. Pediatr. Cardiol. 1996, 17, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Williamson, G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. Soc. Psychol. Health 1988, 5, 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell, K.E.; Bryant, E.J.; Drapeau, V.; Thivel, D.; Adamo, K.B.; Chaput, J.P. Validation of a child version of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire in a Canadian sample: A psychometric tool for the evaluation of eating behaviour. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 22, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi-Shahri, M.; Fathi-Ashtiani, A.; Azad-Fallah, P.; Gh, A.M. Reliability and validity of the Igroup Presence Questionnaire in Persian language. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2009, 3, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Growth Reference 5–19 Years—BMI-for-Age (5–19 Years). 2007. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/indicators/bmi-for-age (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Debeuf, T.; Verbeken, S.; Van Beveren, M.-L.; Michels, N.; Braet, C. Stress and Eating Behavior: A Daily Diary Study in Youngsters. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 413828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyldelund, N.B.; Dalgaard, V.L.; Byrne, D.V.; Andersen, B.V. Why Being ‘Stressed’ Is ‘Desserts’ in Reverse—The Effect of Acute Psychosocial Stress on Food Pleasure and Food Choice. Foods 2021, 11, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reents, J.; Pedersen, A. Differences in Food Craving in Individuals With Obesity With and Without Binge Eating Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 660880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Garcia, M.; Gutierrez-Maldonado, J.; Treasure, J.; Vilalta-Abella, F. Craving for Food in Virtual Reality Scenarios in Non-Clinical Sample: Analysis of its Relationship with Body Mass Index and Eating Disorder Symptoms. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2015, 23, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werthmann, J.; Tuschen-Caffier, B.; Ströbele, L.; Kübel, S.L.; Renner, F. Healthy cravings? Impact of imagined healthy food con-sumption on craving for healthy foods and motivation to eat healthily—Results of an initial experimental study. Appetite 2023, 183, 106458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, D.; Moss, R.H.; Sykes-Muskett, B.; Conner, M.; O’Connor, D.B. Stress and eating behaviors in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite 2018, 123, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, D.; Miriam, C.; Rosa, F.; Mark, C. Unhealthy eating and academic stress: The moderating effect of eating style and BMI. Health Psychol. 2020, 30, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padfield, G.J.; Escudero, C.; DeSouza, A.; Steinberg, C.; Gibbs, K.; Puyat, J.H.; Lam, P.Y.; Sanatani, S.; Sherwin, E.; Potts, J.E.; et al. Characterization of Myocardial Repolarization Reserve in Adolescent Females with Anorexia Nervosa. Circulation 2016, 133, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín Rivada, A.; Parera Pinilla, C.; Baño Rodrigo, A.; Jiménez García, R.; Tamariz Martel-Moreno, A. Electrocardiographic and echocar-diographic abnormalities in female adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Rev. Pediatr. Aten. Primaria 2020, 22, e13–e19. [Google Scholar]

- Tomar, A.; Ahluwalia, H.; Isser, H.S.; Gulati, S.; Kumar, P.; Yadav, I. Analysis of ventricular repolarization parameters and heart rate variability in obesity: A comparative study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayon, M.; Latchupatula, L.; Kacer, E.; Shanjer, M.; Weiss, E.; Amar, S.; Zweig, N.; Ghadim, M.; Portman, R.; Balakrishnan, N.; et al. QTc Interval Prolongation and Its Association with Electrolyte Abnormali-ties and Psychotropic Drug Use Among Patients with Eating Disorders. CJC Pediatr. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2023, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi-Renani, S.; Gharebaghi, M.; Kamalian, E.; Hajghassem, H.; Ghanbari, A.; Karimi, A.; Mansoury, B.; Dayari, M.S.; Nemati, M.K.; Karimi, A.; et al. Clinical Validation of a Smartphone-based Handheld ECG Device: A Validation Study. Crit. Pathw. Cardiol. 2022, 21, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenkerk, D.; A La Fontaine, L.; Van Kuijk, S.; Faber, C.G.; Vernooy, K.; Linz, D.; Hermans, B.J.M. Validation of a mobile 6-lead ECG device for annual routine assessment of ECG intervals in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients. EP Eur. 2025, 27, euaf085.842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klier, K.; Koch, L.; Graf, L.; Schinköthe, T.; Schmidt, A. Diagnostic Accuracy of Single-Lead Electrocardiograms Using the Kardia Mobile App and the Apple Watch 4: Validation Study. JMIR Cardio 2023, 7, e50701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moïse-Richard, A.; Ménard, L.; Bouchard, S.; Leclercq, A.-L. Real and virtual classrooms can trigger the same levels of stuttering severity ratings and anxiety in school-age children and adolescents who stutter. J. Fluency Disord. 2021, 68, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waal, N.E.; Janssen, L.; Antheunis, M.; Culleton, E.; van der Laan, L.N. The appeal of virtual chocolate: A system-atic comparison of psychological and physiological food cue responses to virtual and real food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 90, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Participants (N = 38) | Sex (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | ||

| Age (years) | 15.82 ± 0.12 | - | - |

| Anthropometric parameters | - | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) | 20.01 ± 0.67 | ||

| Underweight (<−1 SD) (%, N) 1 | 42.1 (16) | 25 | 75 |

| Normal weight (−1 SD–+1 SD) (%, N) 1 | 36.8 (14) | 28.6 | 71.4 |

| Overweight (>+1 SD) (%, N) 1 | 21.1 (8) | 50 | 50 |

| VR TSST | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Pre VR-TSST | Post VR-TSST | p-Value 1 | Cohen’s d (95% CI) 3 | Cronbach’s α |

| Primary outcomes | |||||

| Electrocardiogram measures | |||||

| QTc Fridericia (ms) | 431.73 ± 34.55 | 429.92 ± 37.90 | 0.48 | 0.05 (−3.44–7.06) | - |

| PQ (ms) | 146.13 ± 18.08 | 140.58 ± 17.42 | 0.02 | 0.31 (0.76–10.34) | - |

| HR (bpm) | 89.32 ± 13.29 | 89.45 ± 14.47 | 0.85 | −0.01 (−1.55–1.29) | - |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Perceived stress | Questionnaires | - | - | ||

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | 33.18 | ||||

| Stress and Anxiety Assessment (VAS method) | |||||

| How stressed are you feeling right now? | - | 3.47 ± 1.91 | - | - | - |

| How anxious are you feeling right now? | - | 3.32 ± 1.84 | - | - | - |

| Eating behavior parameters 2 | |||||

| CR-factor | 20.21 ± 5.13 | - | - | - | 0.80 |

| UE-factor | 13.89 ± 3.79 | - | - | - | 0.76 |

| EE-factor | 12.08 ± 3.96 | - | - | - | 0.73 |

| Appetite and craving ratings (VAS method) | |||||

| How strong is your desire to eat right now? | - | 3.84 ± 2.21 | - | - | - |

| How strong is your desire to eat sweets right now? | - | 2.84 ± 1.65 | - | - | - |

| Supermarket exposure | |||||

| VR Supermarket | Post VR Supermarket | ||||

| Primary Outcomes | |||||

| Fatty food desire | 3.91 ± 1.49 | - | |||

| Fatty food anxiety | 2.56 ± 1.61 | ||||

| Sweet food desire | 4.85 ± 1.58 | - | |||

| Sweet food anxiety | 2.57 ± 1.41 | - | |||

| Healthy food desire | 3.0.5 ± 1.42 | - | |||

| Healthy food anxiety | 2.10 ± 1.23 | - | |||

| Perceived VR exposure | |||||

| Secondary Outcomes | - | ||||

| VR supermarket immersion | 4.55 ± 1.85 | ||||

| VR classroom immersion | 4.79 ± 1.66 | - | |||

| VR supermarket realism | 3.32 ± 1.64 | - | |||

| VR classroom realism | 3.13 ± 1.54 | - | |||

| VR stress | 3.82 ± 1.72 | - | |||

| VR discomfort | 1.84 ± 1.17 | - | |||

| VR performance | 4.87 ± 1.39 | - | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor UE | −0.27 | 0.60 *** | 0.31 | 0.36 * | −0.14 | 0.357 * | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.19 | |

| Factor CR | 0.04 | 0.16 | −0.17 | −0.12 | −0.28 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.07 | ||

| Factor EE | 0.17 | 0.30 | −0.30 | 0.32 | −0.22 | −0.23 | −0.05 | −0.17 | |||

| PSS score | 0.11 | −0.19 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.35 * | 0.29 | 0.12 | ||||

| %Δ QTc | −0.10 | 0.76 *** | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.04 | |||||

| %Δ PQ | −0.12 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.22 | ||||||

| %Δ HR | 0.07 | 0.21 | −0.13 | −0.20 | |||||||

| VAS stress | 0.83 *** | 0.22 | 0.08 | ||||||||

| VAS anxiety | 0.17 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| VAS appetite | 0.29 | ||||||||||

| VAS sweet craving |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty food desire | 0.35 * | −0.30 | 0.025 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.53 *** | 0.49 ** | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| Sweet food desire | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.00 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.33 * | 0.39 * |

| Healthy food desire | −0.22 | −0.15 | −0.36 * | −0.10 | −0.16 | 0.41 * | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| Fatty food anxiety | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.10 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.65 *** | 0.76 *** | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| Sweet food anxiety | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.59 *** | 0.71 *** | −0.03 | 0.00 |

| Healthy food anxiety | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.57 *** | 0.67 *** | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| VR supermarket immersion | −0.12 | 0.33 | −0.51 *** | 0.04 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 | −0.01 |

| VR supermarket realism | 0.15 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.19 | −0.25 | 0.13 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.09 | −0.01 |

| VR supermarket stress | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.36 * | −0.23 | −0.25 |

| Unstd. Beta | Std. Error | Std Beta | t | Sign. p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor CR | −0.40 | 0.21 | −0.29 | −1.87 | 0.07 |

| Factor EE | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.52 | 3.66 | 0.00 |

| PSS | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 1.76 | 0.08 |

| %Δ QTc Fridericia | 0.51 | 0.21 | 0.36 | 2.37 | 0.02 |

| %Δ PQ | −0.06 | 0.09 | −0.11 | −0.70 | 0.48 |

| %Δ HR | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 2.45 | 0.01 |

| VAS stress | 0.10 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.81 |

| VAS anxiety | −0.02 | 0.46 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.95 |

| VAS sweet craving | −0.44 | 0.51 | −0.14 | −0.86 | 0.39 |

| VAS appetite | 0.22 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.56 |

| Fatty food desire | 1.30 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 2.46 | 0.01 |

| Sweet food desire | −0.12 | 0.53 | −0.03 | −0.22 | 0.82 |

| Healthy food desire | −0.74 | 0.58 | −0.20 | −1.27 | 0.21 |

| Fatty food anxiety | −0.10 | 0.52 | −0.03 | −0.19 | 0.84 |

| Sweet food anxiety | −0.09 | 0.60 | −0.02 | −0.16 | 0.87 |

| Healthy food anxiety | −0.00 | 0.76 | −0.00 | −0.00 | 0.99 |

| df | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Sphericity assumed | 2 | 29.82 | 0.00 | 0.46 |

| Food ZUE_UNCONTROLLED_EATING | Sphericity assumed | 2 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| Food ZCR_COGNITIVE_RESTRAINT | Sphericity assumed | 2 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.00 |

| Food ZEE_EMOTIONAL_EATING | Sphericity assumed | 2 | 1.37 | 0.26 | 0.03 |

| (I) Food | (J) Food | Std. Error | Sig. b | 95% Confidence Interval for Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| 1. Fatty food desire | 2. Sweet food desire | 0.25 | 0.00 | −1.58 | −0.30 |

| 3. Healthy food desire | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 1.40 | |

| 2. Sweet food desire | 1. Fatty food desire | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 1.58 |

| 3. Healthy food desire | 0.23 | 0.00 | 1.22 | 2.39 | |

| 3. Healthy food desire | 1. Fatty food desire | 0.21 | 0.00 | −1.40 | −0.31 |

| 2. Sweet food desire | 0.23 | 0.00 | −2.39 | −1.22 | |

| Model | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig. | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UE and supermarket immersion | |||||||

| 1. Stress | 27.68 | 13.84 | 0.51 | 0.16 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| 2. Supermarket immersion | 75.81 | 25.27 | 0.95 | 0.27 | 0.07 | −0.00 | −0.00 |

| 3. Stress and supermarket interaction | 27.25 | 27.25 | 1.03 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| UE and classroom immersion | |||||||

| 1. Stress | 1.49 | 1.49 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.02 |

| 2. Classroom immersion | 10.06 | 5.03 | 0.18 | 0.83 | 0.10 | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| 3. Stress and classroom interaction | 29.64 | 9.88 | 0.35 | 0.78 | 0.17 | 0.03 | −0.05 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig. | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food desire and classroom immersion | |||||||

| 1. Stress | 4.92 | 4.92 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| 2. Classroom immersion | 5.39 | 2.69 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.17 | 0.03 | −0.02 |

| 3. Stress and classroom interaction | 6.14 | 2.04 | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0.18 | 0.03 | −0.05 |

| Sweets desire and classroom immersion | |||||||

| 1. Stress | 1.41 | 1.41 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| 2. Classroom immersion | 6.84 | 3.42 | 1.27 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 3. Stress and classroom interaction | 7.15 | 2.38 | 0.86 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.07 | −0.01 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig. | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty food desire and supermarket immersion | |||||||

| 1. Stress | 25.04 | 25.04 | 15.66 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| 2. Supermarket immersion | 25.44 | 12.72 | 7.79 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.26 |

| 3. Stress and supermarket interaction | 26.27 | 8.75 | 5.28 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 0.25 |

| Sweet food desire and supermarket immersion | |||||||

| 1. Stress | 1.35 | 1.35 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| 2. Supermarket immersion | 7.96 | 3.98 | 1.63 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| 3. Stress and supermarket interaction | 8.26 | 2.75 | 1.10 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| Healthy food desire and supermarket immersion | |||||||

| 1. Stress | 3.69 | 3.69 | 1.85 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| 2. Supermarket immersion | 8.08 | 4.04 | 2.10 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| 3. Stress and supermarket interaction | 8.16 | 2.72 | 1.37 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onita, C.A.; Matei, D.-V.; Chelarasu, E.; Lupu, R.G.; Petrescu-Miron, D.; Visnevschi, A.; Vudu, S.; Corciova, C.; Fuior, R.; Tupita, N.; et al. Virtual Reality Trier Social Stress and Virtual Supermarket Exposure: Electrocardiogram Correlates of Food Craving and Eating Traits in Adolescents. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3924. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243924

Onita CA, Matei D-V, Chelarasu E, Lupu RG, Petrescu-Miron D, Visnevschi A, Vudu S, Corciova C, Fuior R, Tupita N, et al. Virtual Reality Trier Social Stress and Virtual Supermarket Exposure: Electrocardiogram Correlates of Food Craving and Eating Traits in Adolescents. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3924. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243924

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnita, Cristiana Amalia, Daniela-Viorelia Matei, Elena Chelarasu, Robert Gabriel Lupu, Diana Petrescu-Miron, Anatolie Visnevschi, Stela Vudu, Calin Corciova, Robert Fuior, Nicoleta Tupita, and et al. 2025. "Virtual Reality Trier Social Stress and Virtual Supermarket Exposure: Electrocardiogram Correlates of Food Craving and Eating Traits in Adolescents" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3924. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243924

APA StyleOnita, C. A., Matei, D.-V., Chelarasu, E., Lupu, R. G., Petrescu-Miron, D., Visnevschi, A., Vudu, S., Corciova, C., Fuior, R., Tupita, N., Bouchard, S., & Mocanu, V. (2025). Virtual Reality Trier Social Stress and Virtual Supermarket Exposure: Electrocardiogram Correlates of Food Craving and Eating Traits in Adolescents. Nutrients, 17(24), 3924. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243924