Body Composition, Microbiome and Physical Activity in Workers Under Intermittent Hypobaric Hypoxia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nutritional Status and Body Composition Assessment

2.2. Gut Microbiota Analysis

2.3. Determination of Physical Activity Level

2.4. Ethical Aspects

2.5. Statistical Analysis

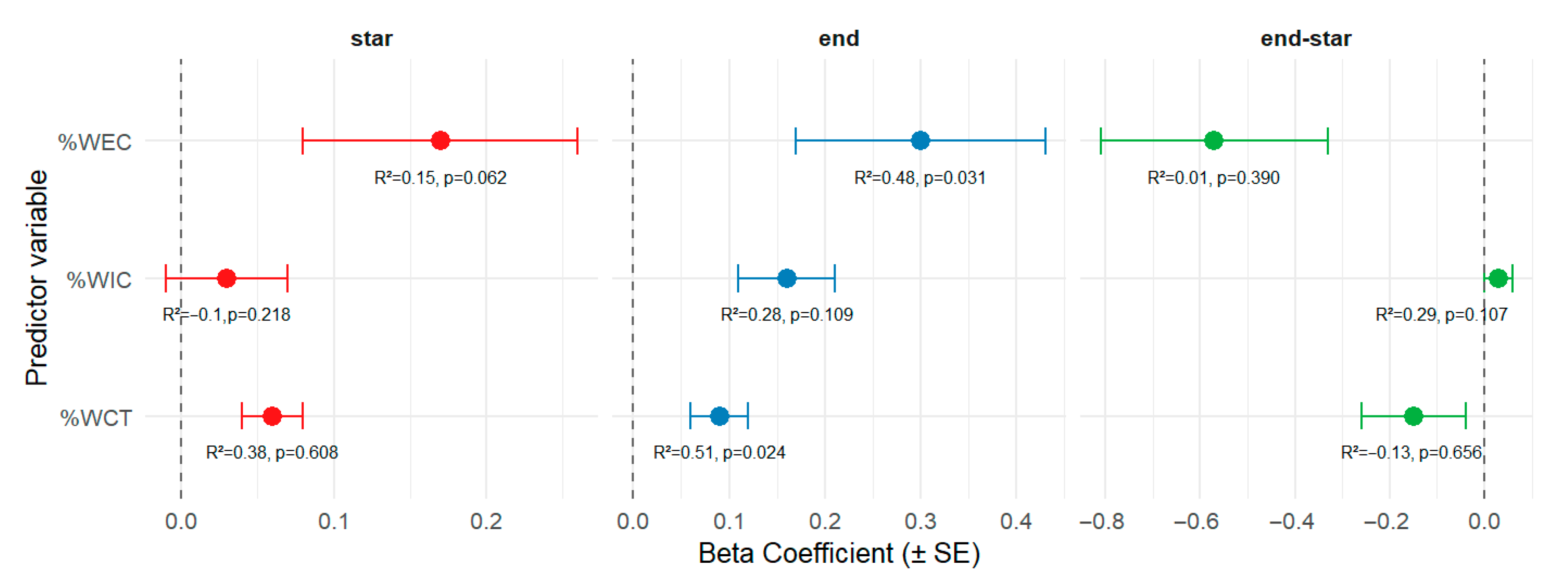

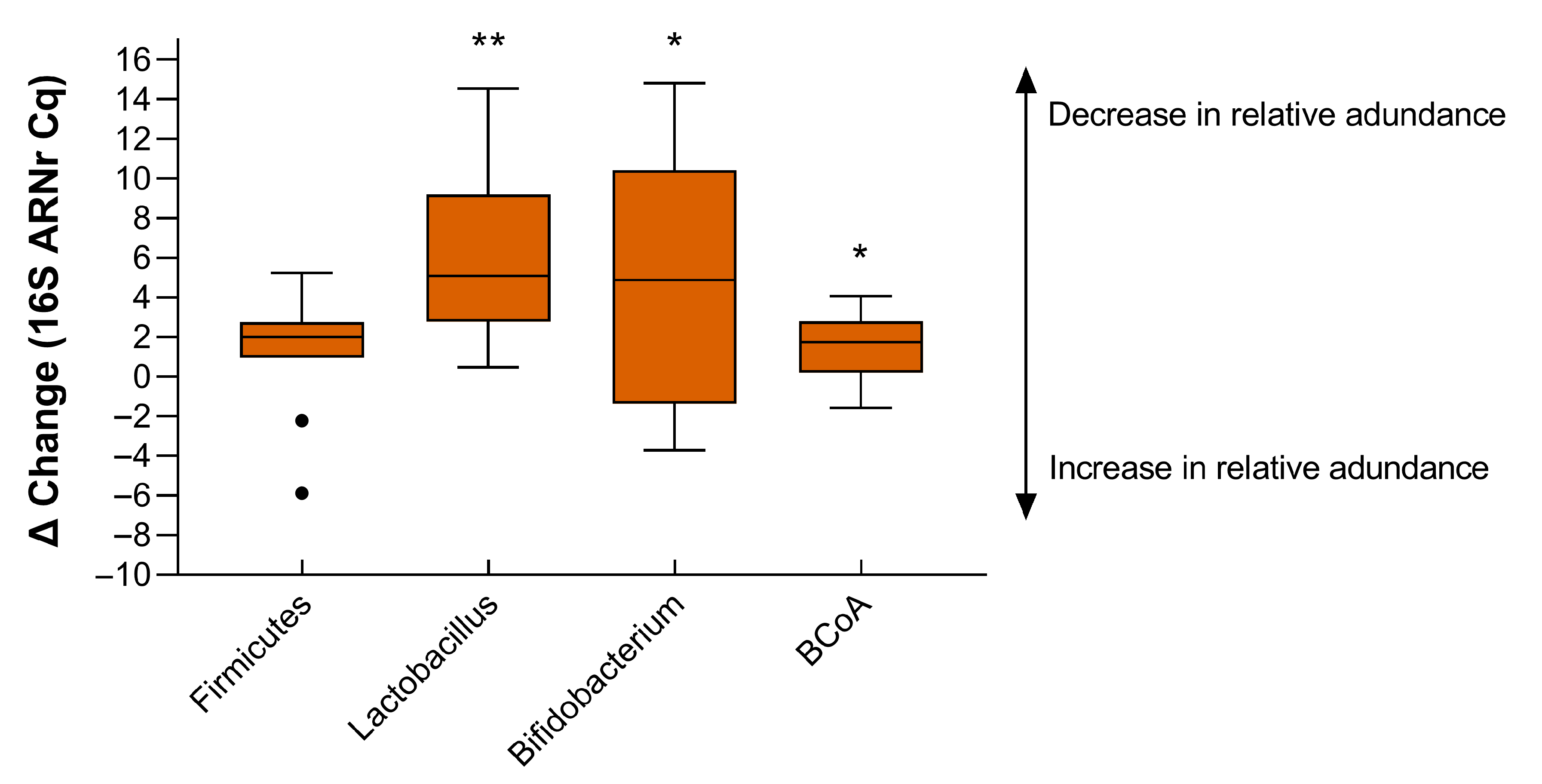

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tremblay, J.C.; Ainslie, P.N. Global and country-level estimates of human population at high altitude. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2102463118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getu, A. Ethiopian Native Highlander’s Adaptation to Chronic High-Altitude Hypoxia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5749382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.A.; Murray, A.J.; Simonson, T.S. Notch Signaling and Cross-Talk in Hypoxia: A Candidate Pathway for High-Altitude Adaptation. Life 2022, 12, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.M.; Luks, A.M. High Altitude. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 44, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, C.V. Barometric Pressure at High Altitude: Revisiting West’s Prediction Equation, and More. High. Alt. Med. Biol. 2023, 24, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrlin, J.P.; Hallén, J. Linear decrease in O2max and performance with increasing altitude in endurance athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 96, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, M.; Bilo, G.; Caravita, S.; Parati, G. Blood pressure and altitude: Physiological responses and clinical management [Blood pressure and high altitude: Physiological response and clinical management]. Medwave 2021, 21, e8194. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) (ESO/NAOJ)/NRAO). About ALMA. Available online: https://www.almaobservatory.org/es/inicio/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Pizarro-Montaner, C.; Cancino-Lopez, J.; Reyes-Ponce, A.; Flores-Opazo, M. Interplay between rotational work shift and high altitude-related chronic intermittent hypobaric hypoxia on cardiovascular health and sleep quality in Chilean miners. Ergonomics 2020, 63, 1281–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Jofre, R.; Moraga, D.; Moraga, F.A. The Effect of Chronic Intermittent Hypobaric Hypoxia on Sleep Quality and Melatonin Serum Levels in Chilean Miners. Front. Physiol. 2022, 12, 809360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedreros-Lobos, A.; Calderón-Jofré, R.; Moraga, D.; Moraga, F.A. Cardiovascular Risk Is Increased in Miner’s Chronic Intermittent Hypobaric Hypoxia Exposure from 0 to 2500 m? Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 647976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscor, G.; Torrella, J.R.; Corral, L.; Ricart, A.; Javierre, C.; Pages, T.; Ventura, J.L. Physiological and Biological Responses to Short-Term Intermittent Hypobaric Hypoxia Exposure: From Sports and Mountain Medicine to New Biomedical Applications. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Chen, D.; Xiao, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.-J.; Peng, H.; Han, C.; Yao, H. High-altitude-induced alterations in intestinal microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1369627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, B.; Ghosh, T.S.; Kedia, S.; Rampal, R.; Saxena, S.; Bag, S.; Mitra, R.; Dayal, M.; Mehta, O.; Surendranath, A.; et al. Analysis of the Gut Microbiome of Rural and Urban Healthy Indians Living in Sea Level and High Altitude Areas. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleessen, B.; Schroedl, W.; Stueck, M.; Richter, A.; Rieck, O.; Krueger, M. Microbial and immunological responses relative to high-altitude exposure in mountaineers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, J.P.; Berryman, C.E.; Young, A.J.; Radcliffe, P.N.; Branck, T.A.; Pantoja-Feliciano, I.G.; Rood, J.C.; Pasiakos, S.M. Associations between the gut microbiota and host responses to high altitude. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2018, 315, G1003–G1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Xie, Y.; Xu, C. Association analysis of gut microbiota-metabolites-neuroendocrine changes in male rats acute exposure to simulated altitude of 5500 m. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Cantabrana, C.; Delgado, S.; Ruiz, L.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Sánchez, B.; Margolles, A. Bifidobacteria and Their Health-Promoting Effects. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Un-Nisa, A.; Khan, A.; Zakria, M.; Siraj, S.; Ullah, S.; Tipu, M.K.; Ikram, M.; Kim, M.O. Updates on the Role of Probiotics Against Different Health Issues: Focus on Lactobacillus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Zhang, S.; Xu, H.; Kong, F.; Yu, X.; Wang, P.; Yang, M.; Li, D.; Zhang, M.; Ni, Q.; et al. Gut microbiota of Tibetans and Tibetan pigs varies between high and low altitude environments. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 235, 126447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, P.; Hosseini, S.A.; Ghaffari, S.; Tutunchi, H.; Ghaffari, S.; Mosharkesh, E.; Asghari, S.; Roshanravan, N. Role of Butyrate, a Gut Microbiota Derived Metabolite, in Cardiovascular Diseases: A comprehensive narrative review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 837509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, W.; Chen, G.; Hu, G.; Jia, J. Faecalibacterium duncaniae Mitigates Intestinal Barrier Damage in Mice Induced by High-Altitude Exposure by Increasing Levels of 2-Ketoglutaric Acid. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karl, J.P.; Fagnant, H.S.; Radcliffe, P.N.; Wilson, M.; Karis, A.J.; Sayers, B.; Wijeyesekera, A.; Gibson, G.R.; Lieberman, H.R.; Giles, G.E.; et al. Gut microbiota-targeted dietary supplementation with fermentable fibers and polyphenols prevents hypobaric hypoxia-induced increases in intestinal permeability. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2025, 329, R378–R399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, J.V.; Byrne-Quinn, E.; Sodal, I.E.; Friesen, W.O.; Underhill, B.; Filley, G.F.; Grover, R.F. Hypoxic ventilatory drive in normal man. J. Clin. Investig. 1970, 49, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bärtsch, P.; Maggiorini, M.; Ritter, M.; Noti, C.; Vock, P.; Oelz, O. Prevention of high-altitude pulmonary edema by nifedipine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 325, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parati, G.; Agostoni, P.; Basnyat, B.; Bilo, G.; Brugger, H.; Coca, A.; Festi, L.; Giardini, G.; Lironcurti, A.; Luks, A.M.; et al. Clinical recommendations for high altitude exposure of individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions: A joint statement by the European Society of Cardiology, the Council on Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology, the European Society of Hypertension, the International Society of Mountain Medicine, the Italian Society of Hypertension and the Italian Society of Mountain Medicine. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, I.; Aravena, R.; Soza, D.; Morales, A.; Riquelme, S.; Calderon-Jofré, R.; Moraga, F.A. Comparison Between Pressure Swing Adsorption and Liquid Oxygen Enrichment Techniques in the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array Facility at the Chajnantor Plateau (5050 m). Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 775240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.B. Commuting to high altitude: Value of oxygen enrichment of room air. High. Alt. Med. Biol. 2002, 3, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matamala Pizarro, J.; Aguayo Fuenzalida, F. Mental health in mine workers: A literature review. Ind. Health 2021, 59, 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, R.T.; Burtscher, J.; Richalet, J.P.; Millet, G.P.; Burtscher, M. Impact of High Altitude on Cardiovascular Health: Current Perspectives. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayser, B.; Verges, S. Hypoxia, energy balance, and obesity: An update. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.M.; Lin, H.Y.; Kuo, C.H. Altitude training improves glycemic control. Chin. J. Physiol. 2013, 56, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, G.; Leyton, B.; Aguirre, C.; Anziani, A.; Weisstaub, G.; Corvalán, C. Anthropometric and bioimpedance equations for fat and fat-free mass in Chilean children 7-9 years of age. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llames, L.; Baldomero, V.; Iglesias, M.L.; Rodota, L.P. Valores del ángulo de fase por bioimpedancia eléctrica; estado nutricional y valor pronóstico [Values of the phase angle by bioelectrical impedance; nutritional status and prognostic value]. Nutr. Hosp. 2013, 28, 286–295. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, V.S.; Vieira, M.F.S. International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK) Global: International accreditation scheme of the competent anthropometrist. Rev. Bras. Cineantropometria Desempenho Humano 2020, 22, 70517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Nguo, K.; Boneh, A.; Truby, H. The Validity of Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis to Measure Body Composition in Phenylketonuria. JIMD Rep. 2018, 42, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottawea, W.; Sultan, S.; Landau, K.; Bordenave, N.; Hammami, R. Evaluation of the Prebiotic Potential of a Commercial Synbiotic Food Ingredient on Gut Microbiota in an Ex Vivo Model of the Human Colon. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Palencia, N.M.; Solera-Martínez, M.; Gracia-Marco, L.; Silva, P.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Cañete-García-Prieto, J.; Sánchez-López, M. Levels and Patterns of Objectively Assessed Physical Activity and Compliance with Different Public Health Guidelines in University Students. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarkowski, M. Kolejna nowelizacja Deklaracj Helsińskiej [Helsinki Declaration–next version]. Pol. Merkur. Lekarski. 2014, 36, 295–297. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, Y.; Joki, N.; Yamazaki, K.; Kawamura, T.; Tai, R.; Oguchi, H.; Yuasa, R.; Sakai, K. Changes in the fluid volume balance between intra- and extracellular water in a sample of Japanese adults aged 15–88 yr old: A cross-sectional study. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2018, 314, F614–F622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.C.; Alves Junior, C.A.S.; Silva, A.M.; Silva, D.A.S. Phase angle and body composition: A scoping review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 56, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Mejías, J.; Rivarola, E.; Diaz, E.; Salazar, G.; Toro, D.; Villegas, F.; Gómez, R.; Cossio, M.; López, M.A.; Merellano-Navarro, E. Somatotype and body composition of porters and guides on Mount Aconcagua, Argentina. Rev. Fac. Cien Med. Univ. Nac. Córdoba 2018, 44, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, B.; Katch, F.; Katch, V. Physical activity at medium and high altitudes. In Fisiología del Ejercicio, Nutrición, Rendimiento y Salud; Wolters Kluwer Healt/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 598–600. [Google Scholar]

- Brunser, T.O. The role of bifidobacteria in the functioning of the human body. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2013, 40, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Zhuang, D.H.; Li, Y.C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Ge, M.X.; Xue, T.Y.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Yin, F.Q.; et al. Gut microbiota contributes to high-altitude hypoxia acclimatization of human populations. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres-Mejías, J.; Arriaza, K.; Mena, F.; Rivarola, E.; Paredes, P.; Ahmad, H.; López, I.; Soza, D.; Pino-Villalón, J.L.; López-Espinoza, M.Á.; et al. Body Composition, Microbiome and Physical Activity in Workers Under Intermittent Hypobaric Hypoxia. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3919. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243919

Torres-Mejías J, Arriaza K, Mena F, Rivarola E, Paredes P, Ahmad H, López I, Soza D, Pino-Villalón JL, López-Espinoza MÁ, et al. Body Composition, Microbiome and Physical Activity in Workers Under Intermittent Hypobaric Hypoxia. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3919. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243919

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres-Mejías, Jorge, Karem Arriaza, Francisco Mena, Evangelina Rivarola, Patricio Paredes, Husam Ahmad, Iván López, Daniel Soza, José Luis Pino-Villalón, Miguel Ángel López-Espinoza, and et al. 2025. "Body Composition, Microbiome and Physical Activity in Workers Under Intermittent Hypobaric Hypoxia" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3919. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243919

APA StyleTorres-Mejías, J., Arriaza, K., Mena, F., Rivarola, E., Paredes, P., Ahmad, H., López, I., Soza, D., Pino-Villalón, J. L., López-Espinoza, M. Á., Duran-Agüero, S., & Merellano-Navarro, E. (2025). Body Composition, Microbiome and Physical Activity in Workers Under Intermittent Hypobaric Hypoxia. Nutrients, 17(24), 3919. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243919