Micronutrient Testing, Supplement Use, and Knowledge Gaps in a National Adult Population: Evidence from Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Study Design and Setting

2.3. Study Population and Sampling

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Management and Variable Definition

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Prevalence of Micronutrient Deficiency and Testing

3.3. Associations Between Participant Characteristics and Micronutrient Status

3.4. Knowledge Level Regarding Vitamin D, Vitamin B12, and Iron: Deficiency Symptoms, Sources, and Supplementation

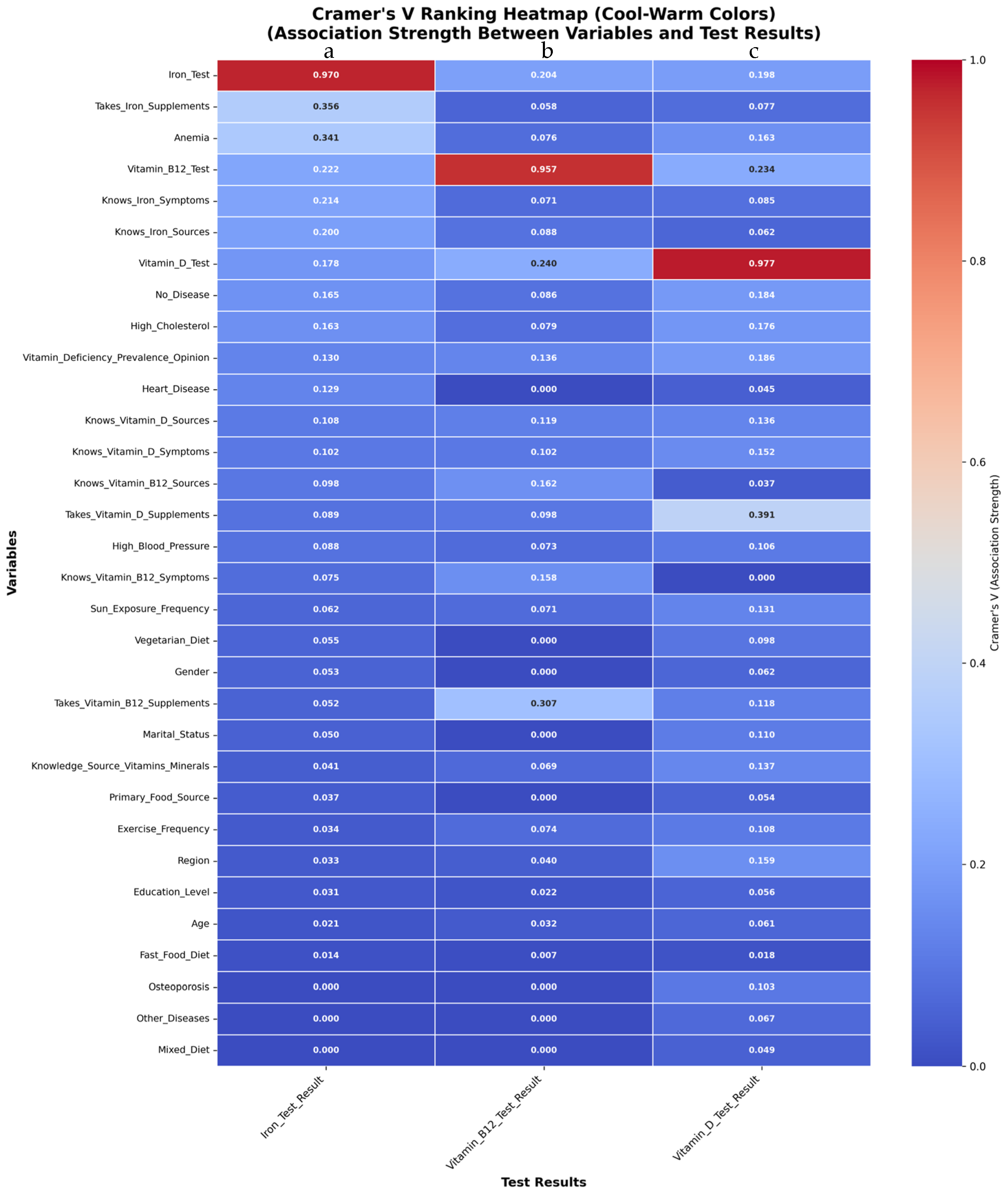

3.5. Associations Between Clinical, Behavioral, and Sociodemographic Variables and Laboratory Findings

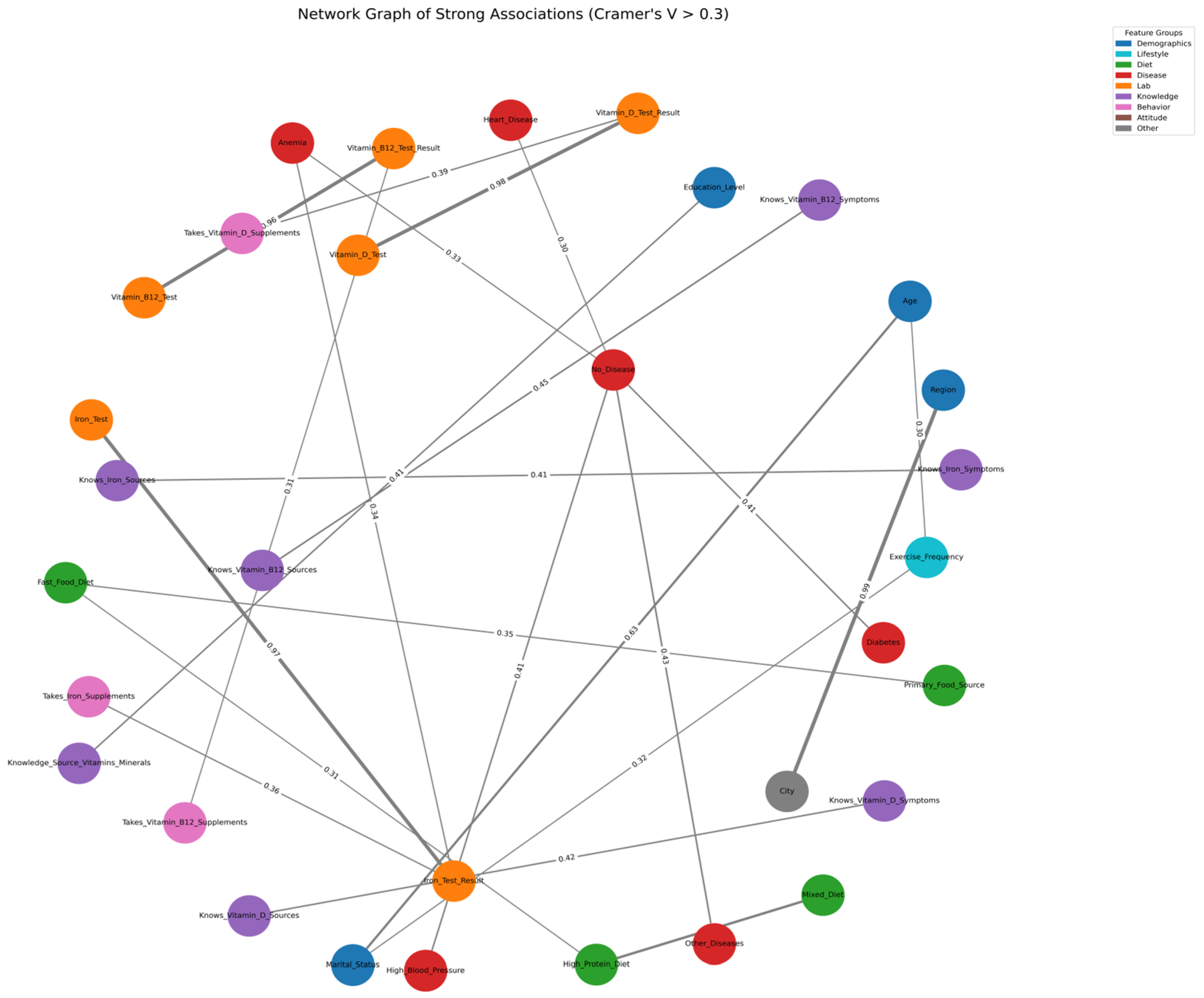

3.6. Network Analysis of Strong Categorical Associations

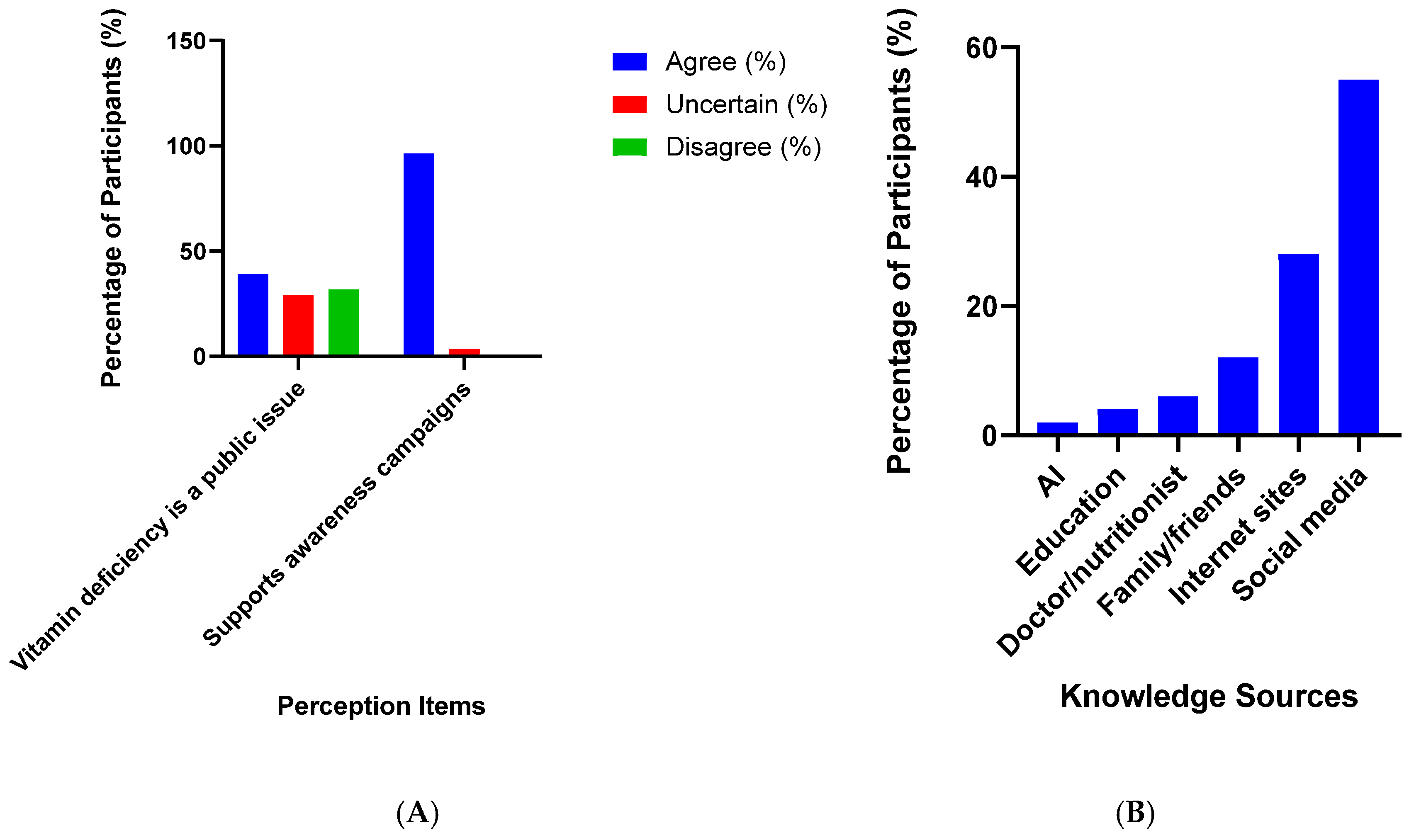

3.7. Sources of Knowledge and Public Perceptions

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biesalski Hans, K.; Jana, T. Micronutrients in the life cycle: Requirements and sufficient supply. NFS J. 2018, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuchi, C.G.; Igwe, V.S.; Amagwula, I.O.; Echeta, C.K. Health benefits of micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) and their associated deficiency diseases: A systematic review. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 3, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G.A.; Beal, T.; Mbuya, M.N.N.; Luo, H.; Neufeld, L.M. Micronutrient deficiencies among preschool-aged children and women of reproductive age worldwide: A pooled analysis of individual-level data from population-representative surveys. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e1590–e1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabler, S.P. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C. Iron-deficiency anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1832–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.K.; Dhuli, K.; Donato, K.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Connelly, S.T.; Bellinato, F.; Gisondi, P.; et al. Main nutritional deficiencies. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63 (Suppl. S3), E93–E101. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, S.N.A.; Anastasiou, E.A.; Adamantidi, T.; Ofrydopoulou, A.; Letsiou, S.; Tsoupras, A. A Comprehensive Review on the Beneficial Roles of Vitamin D in Skin Health as a Bio-Functional Ingredient in Nutricosmetic, Cosmeceutical, and Cosmetic Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wu, X.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Lu, A.; Zhang, G.; Li, F. Disorders of Calcium and Phosphorus Metabolism and the Proteomics/Metabolomics-Based Research. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 576110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.; Silwal, P.; Kim, I.; Modlin, R.L.; Jo, E.K. Vitamin D-Cathelicidin Axis: At the Crossroads between Protective Immunity and Pathological Inflammation during Infection. Immune Netw. 2020, 20, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; You, H.; Kwon, D.H.; Son, Y.; Lee, G.Y.; Han, S.N. Transcriptome analysis of T cells from Ldlr−/− mice and effects of in vitro vitamin D treatment. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2024, 124, 109510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürler, A.; Erbaş, O. The Role of Vitamin D in Cancer Prevention: A Review of Molecular Mechanisms. J. Exp. Basic Med. Sci. 2022, 3, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Xu, X.J.; Zhang, J.S.; Liu, H.M. Association between Vitamin D Deficiency and Levels of Renin and Angiotensin in Essential Hypertension. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2022, 2022, 8975396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchow, E.G.; Sibilska-Kaminski, I.K.; Plum, L.A.; DeLuca, H.F. Vitamin D esters are the major form of vitamin D produced by UV irradiation in mice. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2022, 21, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Schuit, F.; Antonio, L.; Rastinejad, F. Vitamin D binding protein: A historic overview. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K.; Seth, A.; Marwaha, R.K.; Dhanwal, D.; Aneja, S.; Singh, R.; Sonkar, P. A Randomized controlled trial on safety and efficacy of single intramuscular versus staggered oral dose of 600,000IU Vitamin D in treatment of nutritional rickets. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2014, 60, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PMC. Osteomalacia and Vitamin D Status: A Clinical Update 2020. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7839817/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Moslemi, E.; Musazadeh, V.; Kavyani, Z.; Naghsh, N.; Shoura, S.M.S.; Dehghan, P. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation as an adjunct therapy for improving inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers: An umbrella meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 186, 106484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Amin, A.S.M.; Gupta, V. Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, A.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, V.; Yadav, M. Homocysteine, vitamin B12 and folate level: Possible risk factors in the progression of chronic heart and kidney disorders. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2023, 19, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boachie, J.; Adaikalakoteswari, A.; Samavat, J.; Saravanan, P. Low vitamin B12 and lipid metabolism: Evidence from pre-clinical and clinical studies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Xu, K.; Liu, L.; Zhang, K.; Xia, L.; Zhang, M.; Teng, C.; Tong, H.; He, Y.; Xue, Y.; et al. Vitamin B12 Enhances Nerve Repair and Improves Functional Recovery After Traumatic Brain Injury by Inhibiting ER Stress-Induced Neuron Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umekar, M.; Premchandani, T.; Tatode, A.; Qutub, M.; Raut, N.; Taksande, J.; Hussain, U.M. Vitamin B12 deficiency and cognitive impairment: A comprehensive review of neurological impact. Brain Disord. 2025, 18, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankar, A.; Kumar, A. Vitamin B12 Deficiency. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441923/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Andrès, E.; Terrade, J.E.; Alonso Ortiz, M.B.; Méndez-Bailón, M.; Ghiura, C.; Habib, C.; Lavigne, T.; Jannot, X.; Lorenzo-Villalba, N. Unraveling the Enigma: Food Cobalamin Malabsorption and the Persistent Shadow of Cobalamin Deficiency. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LLacombe, V.; Vinatier, E.; Roquin, G.; Copin, M.-C.; Delattre, E.; Hammi, S.; Lavigne, C.; Annweiler, C.; Blanchet, O.; de la Barca, J.M.C.; et al. Oral vitamin B12 supplementation in pernicious anemia: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 120, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendjayeva, K.; Alieva, A.; Khaydarova, F. What is the minimum dose of vitamin B 12 required to correct the deficiency during long -term metformin use? In Endocrine Abstracts; Bioscientifica: Rignano Flaminio, Italy, 2025; Volume 110, Available online: https://www.endocrine-abstracts.org/ea/0110/ea0110ep899 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Sil, R.; Chakraborti, A.S. Major heme proteins hemoglobin and myoglobin with respect to their roles in oxidative stress—A brief review. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1543455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, B.; Cassagnol, M. Biochemistry, Cytochrome P450. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557698/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Gaur, K.; Pérez Otero, S.C.; Benjamín-Rivera, J.A.; Rodríguez, I.; Loza-Rosas, S.A.; Vázquez Salgado, A.M.; Akam, E.A.; Hernández-Matias, L.; Sharma, R.K.; Alicea, N.; et al. Iron Chelator Transmetalative Approach to Inhibit Human Ribonucleotide Reductase. JACS Au 2021, 1, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, S.; Ripamonti, M.; Moro, A.S.; Cozzi, A. Iron imbalance in neurodegeneration. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbaspour, N.; Hurrell, R.; Kelishadi, R. Review on iron and its importance for human health. J. Res. Med. Sci. Off. J. Isfahan Univ. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Moustarah, F.; Daley, S.F. Dietary Iron. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK540969/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Živanović, N.; Lesjak, M. The influence of plant-based food on bioavailability of iron. Biol. Serbica 2024, 46. Available online: https://ojs.pmf.uns.ac.rs/index.php/dbe_serbica/article/view/18085 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Alhaidari, H.M.; Babtain, F.; Alqadi, K.; Bouges, A.; Baeesa, S.; Al-Said, Y.A. Association between serum vitamin D levels and age in patients with epilepsy: A retrospective study from an epilepsy center in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2022, 42, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alolayan, A.; Al-Wutayd, O. Association between vitamin D status and asthma control levels among children and adolescents: A retrospective cross sectional study in Saudi Arabia. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, M.; Nagy, E.; Abdalbary, M.; Alsayed, M.A.; Ali, A.A.S.; Ahmed, R.M.; Alsuliamany, A.S.M.; Alyami, A.H.; Althaqafi, R.M.; Alsaqqa, R.M.; et al. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Vitamin D Deficiency in High Altitude Region in Saudi Arabia: Three-Year Retrospective Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qahtani, S.M.; Shati, A.A.; Alqahtani, Y.A.; Dawood, S.A.; Siddiqui, A.F.; Zaki, M.S.A.; Khalil, S.N. Prevalence and Correlates of Vitamin D Deficiency in Children Aged Less than Two Years: A Cross-Sectional Study from Aseer Region, Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussaini, A.A.; Alshehry, Z.; AlDehaimi, A.; Bashir, M.S. Vitamin D and iron deficiencies among Saudi children and adolescents: A persistent problem in the 21st Century. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daghri, N.M.; Hussain, S.D.; Ansari, M.G.; Khattak, M.N.; Aljohani, N.; Al-Saleh, Y.; Al-Harbi, M.Y.; Sabico, S.; Alokail, M.S. Decreasing prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the central region of Saudi Arabia (2008–2017). J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 212, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.H.; Elfargani, F.R.; Mohamed, N.; Alhamdi, F.A. Impact of Metformin Therapy on Vitamin B12 Levels in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2025, 8, e70049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zahab, Z.A.; Qureshi, H.; Adham, G.M.; Elzefzafy, W.M.; Zalam, S.S.; Rehan, A.M.; Abdelhameed, M.F.; Bayoumy, A.A.; AlKarkosh, S.K.; Fakhouri, W.G.; et al. Frequency of comorbid diseases with high serum Vitamin B12 levels in patients attending King Salman Medical City (KSAMC), at Madinah. Int. J. Health Sci. 2025, 19, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bin Abdulrahman, K.A.; Alshehri, A.F.; Almutairi, F.M.; Almahyawi, F.A.; Alzahrani, R.S.; Al-Ahmari, O.T.; Alshammari, K.; Aljuhani, T.A.; Alkadi, Y.Y.; Alisi, M.A. Assessing the neurological impact of vitamin B12 deficiency among the population of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1635075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamali, H.A. An Overview of the Incidence, Causes, and Impact of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Saudi Arabia. Clin. Lab. 2025, 71, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlTuraiki, M.A.; Alhabbad, A.S.; Almuyidi, R.M.; AlAtni, B.A.A.; Adnan, A.M.A.; Alammar, D.M.; Almaghrabi, S.F.; Alshammari, S.M.N.; Alshammari, A.M.; Mahmoud Alrihimy, B.; et al. Association of anemia among children and adolescents and childhood complications in Saudi Arabia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. Deporte 2025, 20, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hamali, H.A. Anemia Among Women and Children in Saudi Arabia: Is it a Public Health Burden? Clin. Lab. 2025, 71, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albar, H.T.; Zakri, A.Y.; Ali, A.E.; Labban, S.; Mattar, D.; Azmat, A.; Khan, W.A.; Elamin, M.O.; Osman, A.A. Prevalence of Anemia in Saudi Women of Reproductive Age and its Association with a Family History of Anemia in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Glob. J. Med. Pharm. Biomed. Update 2025, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, M.; Malik, M.; Purohit, A.; Jain, L.; Kaur, K.; Pradhan, P.; Mathew, J.L. Association of iron deficiency and anemia with obesity among children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2025, 26, e13892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugis, A.A.; Bugis, B.; Alzahrani, A.; Alamri, A.H.; Almalki, H.H.; Alshehri, J.H.; Alqarni, A.A.; Turkestani, F. The Associations of Anaemia Status and Body Mass Index with Asthma Severity in Saudi Arabia: A Comparative Study. J. Asthma Allergy 2025, 18, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkalash, S.H.; Odah, M.; Alkenani, H.H.; Hibili, N.H.; Al-Essa, R.S.; Almowallad, R.T.; Aldabali, S. Public knowledge, attitude, and practice toward vitamin D deficiency in Al-Qunfudhah Governorate, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e33756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafiz, M.N.; Agarwal, A.; Suhail, N.; Mohammed, Z.M.; Mohammed, S.A.; Almasmoum, H.A.; Jawad, M.M.; Nofal, W. Awareness and Attitudes Toward Iron Deficiency Anemia Among the Adult Population in the Northern Border Region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study. Hemato 2025, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, I.; Qashqari, H.A.; Alabdali, S.F.; Binsiddiq, Z.H.; Felimban, S.A.; Bahakeem, R.F.; Alansari, A.H. Awareness of iron deficiency anemia among the adult population in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2025, 8, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuair, A.A. Assessment of a school-based, nursing-lead program to combat iron deficiency anemia among Saudi female adolescents: A pilot exploratory study. Discov. Public Health 2025, 22, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–25 | 213 | 12.9 |

| 25–35 | 359 | 21.7 | |

| 35–45 | 535 | 32.4 | |

| 45–55 | 414 | 25.1 | |

| 55+ | 131 | 7.9 | |

| Gender | Female | 869 | 52.6 |

| Male | 783 | 47.4 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 1359 | 82.3 |

| Other | 82 | 5.0 | |

| Single | 211 | 12.8 | |

| Education Level | High School | 168 | 10.2 |

| Less than High School | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Postgraduate | 265 | 16.0 | |

| University | 1217 | 73.7 | |

| Saudi Provinces | Makkah Province | 356 | 21.5 |

| Eastern Province | 327 | 19.8 | |

| Al-Jawf Province | 200 | 12.1 | |

| Asir Province | 159 | 9.6 | |

| Al-Qassim Province | 118 | 7.1 | |

| Tabuk Province | 94 | 5.7 | |

| Riyadh Province | 90 | 5.4 | |

| Al-Madinah Province | 68 | 4.1 | |

| Jazan Province | 64 | 3.9 | |

| Hail Province | 62 | 3.8 | |

| Najran Province | 54 | 3.3 | |

| Northern Borders Province | 49 | 3.0 | |

| Al-Bahah Province | 11 | 0.7 | |

| Self-Reported of Laboratory Testing | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D Test Result | Below Normal | 126 | 7.6% |

| Normal | 383 | 23.2% | |

| Not Tested | 1143 | 69.2% | |

| Vitamin B12 Test Result | Below Normal | 91 | 5.5% |

| Normal | 423 | 25.6% | |

| Not Tested | 1138 | 68.9% | |

| Iron Test Result | Below Normal | 116 | 7.0% |

| Don’t Know | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Normal | 464 | 28.1% | |

| Not Tested | 1071 | 64.8% | |

| (a) | |||||||||||

| Characteristics | Vitamin D Status | ||||||||||

| Below Normal | Normal | Not Tested | χ2 | p-Value | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Age | 18–25 | 21 | 1.3 | 37 | 2.2 | 155 | 9.4 | 21.166 | 0.020 | ||

| 25–35 | 30 | 1.8 | 99 | 6.0 | 230 | 13.9 | |||||

| 35–45 | 47 | 2.8 | 111 | 6.7 | 377 | 22.8 | |||||

| 45–55 | 17 | 1.0 | 101 | 6.1 | 296 | 17.9 | |||||

| 55+ | 11 | 0.7 | 35 | 2.1 | 85 | 5.1 | |||||

| Gender | Female | 71 | 4.3 | 177 | 10.7 | 621 | 37.6 | 8.348 | 0.015 | ||

| Male | 55 | 3.3 | 206 | 12.5 | 522 | 31.6 | |||||

| Marital Status | Married | 79 | 4.8 | 329 | 19.9 | 951 | 57.6 | 43.639 | <0.001 | ||

| Other | 8 | 0.5 | 17 | 1.0 | 57 | 3.5 | |||||

| Single | 39 | 2.4 | 37 | 2.2 | 135 | 8.2 | |||||

| Education Level | High School | 17 | 1.0 | 47 | 2.8 | 104 | 6.3 | 16.290 | 0.012 | ||

| <High School | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | |||||

| Postgraduate | 25 | 1.5 | 71 | 4.3 | 169 | 10.2 | |||||

| University | 83 | 5.0 | 265 | 16.0 | 869 | 52.6 | |||||

| Exercise Frequency | 3–5 days/week | 43 | 2.6 | 163 | 9.9 | 378 | 22.9 | 44.371 | <0.001 | ||

| Daily | 7 | 0.4 | 38 | 2.3 | 78 | 4.7 | |||||

| I do not exercise | 34 | 2.1 | 40 | 2.4 | 140 | 8.5 | |||||

| <3 days/week | 42 | 2.5 | 142 | 8.6 | 547 | 33.1 | |||||

| Smoking Status | No | 110 | 6.7 | 326 | 19.7 | 1035 | 62.7 | 9.106 | 0.011 | ||

| Yes | 16 | 1.0 | 57 | 3.5 | 108 | 6.5 | |||||

| Primary Food Source | Home-cooked food | 43 | 2.6 | 121 | 7.3 | 276 | 16.7 | 13.687 | 0.008 | ||

| Mix of both | 75 | 4.5 | 243 | 14.7 | 814 | 49.3 | |||||

| Restaurants/fast food | 8 | 0.5 | 19 | 1.2 | 53 | 3.2 | |||||

| Meat Diet | No | 28 | 1.7 | 105 | 6.4 | 359 | 21.7 | 5.915 | 0.052 | ||

| Yes | 98 | 5.9 | 278 | 16.8 | 784 | 47.5 | |||||

| Vegetarian Diet | No | 113 | 6.8 | 365 | 22.1 | 1110 | 67.2 | 17.738 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 13 | 0.8 | 18 | 1.1 | 33 | 2.0 | |||||

| High Protein Diet | No | 91 | 5.5 | 264 | 16.0 | 763 | 46.2 | 1.910 | 0.385 | ||

| Yes | 35 | 2.1 | 119 | 7.2 | 380 | 23.0 | |||||

| Fast Food Diet | No | 96 | 5.8 | 311 | 18.8 | 937 | 56.7 | 2.513 | 0.285 | ||

| Yes | 30 | 1.8 | 72 | 4.4 | 206 | 12.5 | |||||

| Diabetes | No | 115 | 7.0 | 351 | 21.2 | 1081 | 65.4 | 5.432 | 0.066 | ||

| Yes | 11 | 0.7 | 32 | 1.9 | 62 | 3.8 | |||||

| Anemia | No | 106 | 6.4 | 373 | 22.6 | 1103 | 66.8 | 46.071 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 20 | 1.2 | 10 | 0.6 | 40 | 2.4 | |||||

| Osteoporosis | No | 122 | 7.4 | 380 | 23.0 | 1141 | 69.1 | 19.370 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | |||||

| Heart Disease | No | 118 | 7.1 | 365 | 22.1 | 1109 | 67.1 | 5.317 | 0.070 | ||

| Yes | 8 | 0.5 | 18 | 1.1 | 34 | 2.1 | |||||

| High Cholesterol | No | 111 | 6.7 | 369 | 22.3 | 1129 | 68.3 | 53.239 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 15 | 0.9 | 14 | 0.8 | 14 | 0.8 | |||||

| Other Diseases | No | 110 | 6.7 | 365 | 22.1 | 1061 | 64.2 | 9.423 | 0.009 | ||

| Yes | 16 | 1.0 | 18 | 1.1 | 82 | 5.0 | |||||

| High Blood Pressure | No | 108 | 6.5 | 352 | 21.3 | 1089 | 65.9 | 20.695 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 18 | 1.1 | 31 | 1.9 | 54 | 3.3 | |||||

| (b) | |||||||||||

| Characteristics | Vitamin B12 Status | ||||||||||

| Below Normal | Normal | Not Tested | χ2 | p-Value | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Age | 18–25 | 9 | 0.5 | 43 | 2.6 | 161 | 9.7 | 11.676 | 0.307 | ||

| 25–35 | 14 | 0.8 | 98 | 5.9 | 247 | 15.0 | |||||

| 35–45 | 36 | 2.2 | 133 | 8.1 | 366 | 22.2 | |||||

| 45–55 | 21 | 1.3 | 114 | 6.9 | 279 | 16.9 | |||||

| 55+ | 11 | 0.7 | 35 | 2.1 | 85 | 5.1 | |||||

| Gender | Female | 53 | 3.2 | 221 | 13.4 | 595 | 36.0 | 1.228 | 0.541 | ||

| Male | 38 | 2.3 | 202 | 12.2 | 543 | 32.9 | |||||

| Marital Status | Married | 71 | 4.3 | 358 | 21.7 | 930 | 56.3 | 3.747 | 0.441 | ||

| Other | 7 | 0.4 | 19 | 1.2 | 56 | 3.4 | |||||

| Single | 13 | 0.8 | 46 | 2.8 | 152 | 9.2 | |||||

| Education Level | High School | 14 | 0.8 | 45 | 2.7 | 109 | 6.6 | 7.654 | 0.265 | ||

| <High School | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.1 | |||||

| Postgraduate | 15 | 0.9 | 79 | 4.8 | 171 | 10.4 | |||||

| University | 62 | 3.8 | 299 | 18.1 | 856 | 51.8 | |||||

| Exercise Frequency | 3–5 days/week | 38 | 2.3 | 173 | 10.5 | 373 | 22.6 | 24.119 | <0.001 | ||

| Daily | 7 | 0.4 | 31 | 1.9 | 85 | 5.1 | |||||

| I do not exercise | 21 | 1.3 | 48 | 2.9 | 145 | 8.8 | |||||

| <3 days/week | 25 | 1.5 | 171 | 10.4 | 535 | 32.4 | |||||

| Smoking Status | No | 82 | 5.0 | 363 | 22.0 | 1026 | 62.1 | 6.073 | 0.048 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 0.5 | 60 | 3.6 | 112 | 6.8 | |||||

| Primary Food Source | Home-cooked food | 29 | 1.8 | 123 | 7.4 | 288 | 17.4 | 3.959 | 0.412 | ||

| Mix of both | 59 | 3.6 | 279 | 16.9 | 794 | 48.1 | |||||

| Restaurants/fast food | 3 | 0.2 | 21 | 1.3 | 56 | 3.4 | |||||

| Meat Diet | No | 29 | 1.8 | 127 | 7.7 | 336 | 20.3 | 0.237 | 0.888 | ||

| Yes | 62 | 3.8 | 296 | 17.9 | 802 | 48.5 | |||||

| Vegetarian Diet | No | 87 | 5.3 | 404 | 24.5 | 1097 | 66.4 | 0.725 | 0.696 | ||

| Yes | 4 | 0.2 | 19 | 1.2 | 41 | 2.5 | |||||

| High Protein Diet | No | 50 | 3.0 | 282 | 17.1 | 786 | 47.6 | 7.948 | 0.019 | ||

| Yes | 41 | 2.5 | 141 | 8.5 | 352 | 21.3 | |||||

| Fast Food Diet | No | 70 | 4.2 | 339 | 20.5 | 935 | 56.6 | 2.077 | 0.354 | ||

| Yes | 21 | 1.3 | 84 | 5.1 | 203 | 12.3 | |||||

| Diabetes | No | 79 | 4.8 | 403 | 24.4 | 1065 | 64.5 | 9.024 | 0.011 | ||

| Yes | 12 | 0.7 | 20 | 1.2 | 73 | 4.4 | |||||

| Anemia | No | 81 | 4.9 | 404 | 24.5 | 1097 | 66.4 | 11.420 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 0.6 | 19 | 1.2 | 41 | 2.5 | |||||

| Osteoporosis | No | 90 | 5.4 | 420 | 25.4 | 1133 | 68.6 | 0.960 | 0.619 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.3 | |||||

| Heart Disease | No | 88 | 5.3 | 405 | 24.5 | 1099 | 66.5 | 0.635 | 0.728 | ||

| Yes | 3 | 0.2 | 18 | 1.1 | 39 | 2.4 | |||||

| High Cholesterol | No | 85 | 5.1 | 406 | 24.6 | 1118 | 67.7 | 12.270 | 0.002 | ||

| Yes | 6 | 0.4 | 17 | 1.0 | 20 | 1.2 | |||||

| Other Diseases | No | 82 | 5.0 | 392 | 23.7 | 1062 | 64.3 | 1.413 | 0.493 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 0.5 | 31 | 1.9 | 76 | 4.6 | |||||

| High Blood Pressure | No | 82 | 5.0 | 385 | 23.3 | 1082 | 65.5 | 10.907 | 0.004 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 0.5 | 38 | 2.3 | 56 | 3.4 | |||||

| (c) | |||||||||||

| Characteristics | Iron Status | ||||||||||

| Below Normal | Don’t Know | Normal | Not Tested | χ2 | p-Value | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Age | 18–25 | 21 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 44 | 2.7 | 148 | 9.0 | 16.133 | 0.373 |

| 25–35 | 22 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 100 | 6.1 | 237 | 14.3 | |||

| 35–45 | 41 | 2.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 163 | 9.9 | 330 | 20.0 | |||

| 45–55 | 22 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 119 | 7.2 | 273 | 16.5 | |||

| 55+ | 10 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 38 | 2.3 | 83 | 5.1 | |||

| Gender | Female | 67 | 4.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 263 | 15.9 | 539 | 32.6 | 7.667 | 0.053 |

| Male | 49 | 3.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 201 | 12.2 | 532 | 32.2 | |||

| Marital Status | Married | 86 | 5.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 388 | 23.5 | 885 | 53.6 | 14.280 | 0.027 |

| Other | 6 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 22 | 1.3 | 54 | 3.3 | |||

| Single | 24 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 54 | 3.3 | 132 | 8.0 | |||

| Education Level | High School | 17 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 47 | 2.8 | 104 | 6.3 | 13.831 | 0.128 |

| <High School | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | |||

| Postgraduate | 18 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 89 | 5.4 | 157 | 9.5 | |||

| University | 81 | 4.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 327 | 19.8 | 809 | 49.0 | |||

| Exercise Frequency | 3–5 days/week | 36 | 2.2 | 1 | 0.1 | 187 | 11.3 | 360 | 21.8 | 14.601 | 0.102 |

| Daily | 8 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 36 | 2.2 | 79 | 4.8 | |||

| I do not exercise | 22 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 60 | 3.6 | 132 | 8.0 | |||

| <3 days/week | 50 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 181 | 11.0 | 500 | 30.3 | |||

| Smoking Status | No | 105 | 6.4 | 1 | 0.1 | 412 | 24.9 | 953 | 57.7 | 0.415 | 0.937 |

| Yes | 11 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 52 | 3.1 | 118 | 7.1 | |||

| Primary Food Source | Home-cooked food | 34 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 137 | 8.3 | 269 | 16.3 | 10.461 | 0.107 |

| Mix of both | 76 | 4.6 | 1 | 0.1 | 296 | 17.9 | 759 | 45.9 | |||

| Restaurants/fast food | 6 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 31 | 1.9 | 43 | 2.6 | |||

| Meat Diet | No | 31 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 144 | 8.7 | 317 | 19.2 | 1.308 | 0.727 |

| Yes | 85 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 320 | 19.4 | 754 | 45.6 | |||

| Vegetarian Diet | No | 110 | 6.7 | 1 | 0.1 | 437 | 26.5 | 1040 | 63.0 | 8.038 | 0.045 |

| Yes | 6 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 27 | 1.6 | 31 | 1.9 | |||

| High Protein Diet | No | 78 | 4.7 | 1 | 0.1 | 307 | 18.6 | 732 | 44.3 | 1.193 | 0.755 |

| Yes | 38 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 157 | 9.5 | 339 | 20.5 | |||

| Fast Food Diet | No | 89 | 5.4 | 1 | 0.1 | 371 | 22.5 | 883 | 53.5 | 3.308 | 0.347 |

| Yes | 27 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 93 | 5.6 | 188 | 11.4 | |||

| Diabetes | No | 108 | 6.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 437 | 26.5 | 1001 | 60.6 | 0.408 | 0.939 |

| Yes | 8 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 27 | 1.6 | 70 | 4.2 | |||

| Anemia | No | 82 | 5.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 448 | 27.1 | 1051 | 63.6 | 195.296 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 34 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.0 | 20 | 1.2 | |||

| Osteoporosis | No | 115 | 7.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 460 | 27.8 | 1067 | 64.6 | 1.663 | 0.645 |

| Yes | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.2 | |||

| Heart Disease | No | 108 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 448 | 27.1 | 1036 | 62.7 | 30.516 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 8 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 16 | 1.0 | 35 | 2.1 | |||

| High Cholesterol | No | 112 | 6.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 444 | 26.9 | 1053 | 63.7 | 46.675 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 4 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | 20 | 1.2 | 18 | 1.1 | |||

| Other Diseases | No | 107 | 6.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 425 | 25.7 | 1003 | 60.7 | 2.274 | 0.517 |

| Yes | 9 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 39 | 2.4 | 68 | 4.1 | |||

| High Blood Pressure | No | 107 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 437 | 26.5 | 1005 | 60.8 | 15.646 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 9 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 27 | 1.6 | 66 | 4.0 | |||

| Q | Do You Know the Symptoms of Deficiency? | |||||

| Yes | May Be | No | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Vitamin D | 700 | 42.4 | 706 | 42.7 | 246 | 14.9 |

| Vitamin B12 | 765 | 46.3 | 362 | 21.9 | 525 | 31.8 |

| Iron | 691 | 41.8 | 473 | 28.6 | 488 | 29.5 |

| Q | Do You Know the Food Sources of These Micronutrients? | |||||

| Yes | May Be | No | ||||

| n | % | N | % | n | % | |

| Vitamin D | 719 | 43.5 | 533 | 32.3 | 400 | 24.2 |

| Vitamin B12 | 744 | 45 | 307 | 18.6 | 601 | 36.4 |

| Iron | 863 | 52.2 | 331 | 20 | 458 | 27.7 |

| Q | Do You Take Supplements? | |||||

| Yes | No | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Vitamin D | 331 | 20 | 1321 | 80 | ||

| Vitamin B12 | 299 | 18.1 | 1353 | 81.9 | ||

| Iron | 371 | 22.5 | 1281 | 77.5 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alrefaei, A.F.; Kabrah, S.M. Micronutrient Testing, Supplement Use, and Knowledge Gaps in a National Adult Population: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243897

Alrefaei AF, Kabrah SM. Micronutrient Testing, Supplement Use, and Knowledge Gaps in a National Adult Population: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243897

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlrefaei, Abdulmajeed Fahad, and Saeed M. Kabrah. 2025. "Micronutrient Testing, Supplement Use, and Knowledge Gaps in a National Adult Population: Evidence from Saudi Arabia" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243897

APA StyleAlrefaei, A. F., & Kabrah, S. M. (2025). Micronutrient Testing, Supplement Use, and Knowledge Gaps in a National Adult Population: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Nutrients, 17(24), 3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243897