Decoding Picky Eating in Children: A Temporary Phase or a Hidden Health Concern?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Definition

- Mild PE: Suboptimal dietary variety or quality without evidence of nutrient deficiencies or growth faltering.

- Moderate PE: Similar restrictive patterns accompanied by laboratory markers of under- or overnutrition or micronutrient insufficiency.

- Severe PE: Extreme food rejection leading to significant nutritional deficiencies, impaired growth trajectories, or marked psychosocial distress.

4. Epidemiology and Prevalence

5. Developmental Considerations and Feeding Milestones

5.1. Infancy (0–6 Months)

5.2. 6–12 Months

5.3. 12–24 Months

5.4. 2–5 Years

6. ARFID and Other Feeding Disorders

7. Contributing Factors

7.1. Genetic Factors

7.2. The Immune Mechanisms

7.3. Psychological and Sensory Processing Issues and Temperament

7.4. Family and Environmental Factors

7.5. Early Feeding Experiences and Trauma

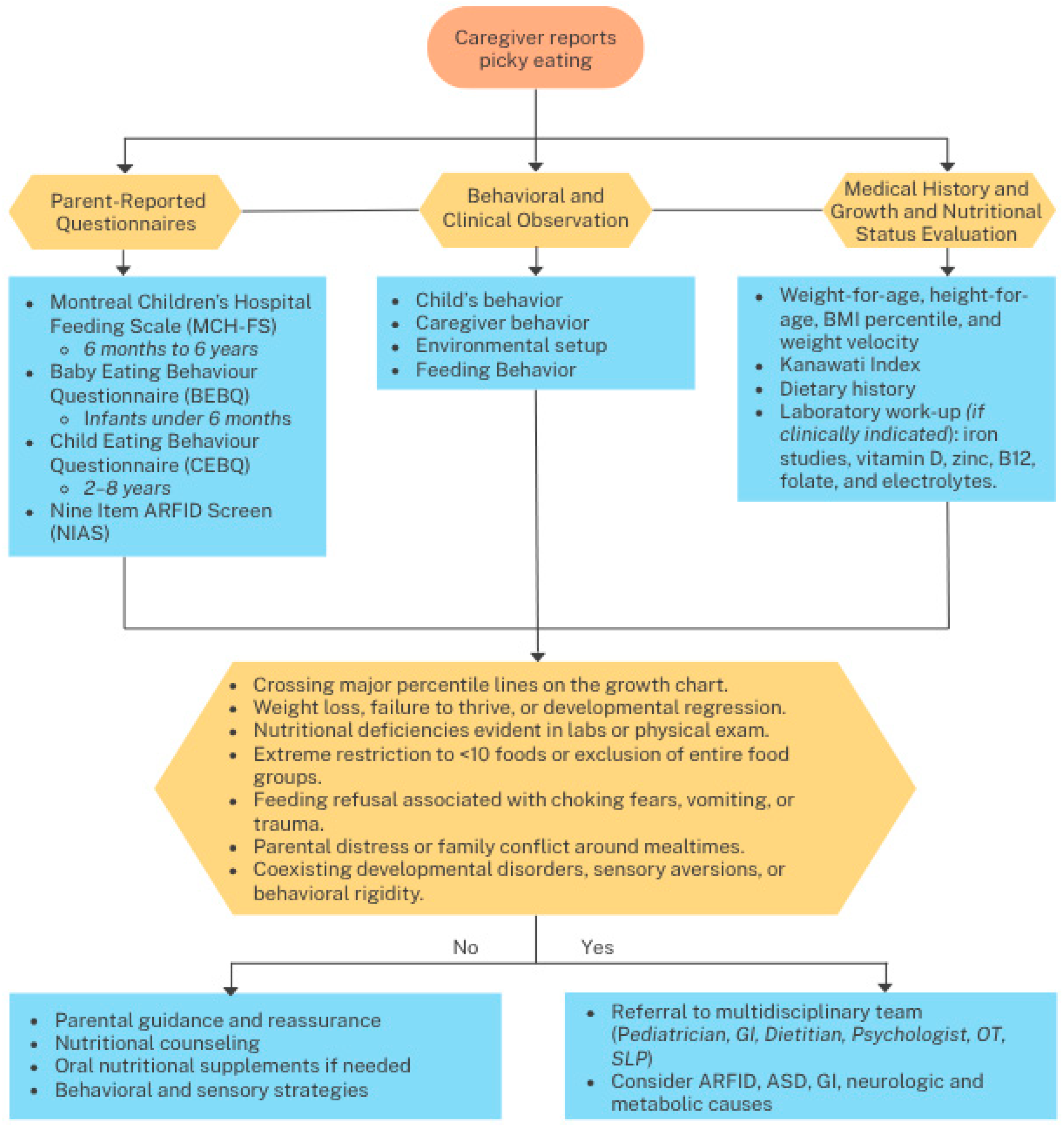

8. Clinical Assessment Tools

9. Diagnostic Considerations and Red Flags for Organic Disease

10. Management Strategies

10.1. Parental Guidance and Psychoeducation Intervention

10.2. Nutritional Interventions

10.3. Sensory Integration and Behavioral Therapy

11. Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

12. Research Gaps and Future Directions

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAP | American Academy of Pediatrics |

| ABA | Applied Behavior Analysis |

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| AN | Anorexia Nervosa |

| ARFID | Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| BEBQ | Baby Eating Behaviour Questionnaire |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CEBQ | Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| EoE | Eosinophilic Esophagitis |

| FED | Feeding and Eating Disorder |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| LD | Linear Dichroism (remove if not relevant; appears in template placeholder) |

| MCH-FS | Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale |

| NIAS | Nine Item ARFID Screen |

| ONS | Oral Nutritional Supplements |

| OT | Occupational Therapist |

| PARDI | Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview |

| PCIT | Parent–Child Interaction Therapy |

| PFD | Pediatric Feeding Disorder |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SLP | Speech–Language Pathologist |

| SIT | Sensory Integration Therapy |

| SOS | Sequential Oral Sensory (approach) |

| UFED | Unspecified Feeding and Eating Disorder |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Fisher, M.; Zimmerman, J.; Bucher, C.; Yadlosky, L.B. ARFID at 10 Years: A Review of Medical, Nutritional and Psychological Evaluation and Management. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2023, 25, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.; Donovan, S.M.; Lee, S. Considering Nature and Nurture in the Etiology and Prevention of Picky Eating: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovey, T.M.; Staples, P.; Gibson, E.L.; Halford, J.C.G. Food Neophobia and ‘Picky/Fussy’ Eating in Children: A Review. Appetite 2007, 50, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, A.T.; Fiorito, L.M.; Lee, Y.; Birch, L.L. Parental Pressure, Dietary Patterns, and Weight Status among Girls Who Are “Picky Eaters”. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.M.; Wernimont, S.M.; Northstone, K.; Emmett, P. Picky/Fussy Eating in Children: Review of Definitions, Assessment, Prevalence and Dietary Intakes. Appetite 2015, 95, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascola, A.J.; Bryson, S.W.; Agras, W.S. Picky Eating during Childhood: A Longitudinal Study to Age 11years. Eat. Behav. 2010, 11, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstein, S.; Laniado, D.; Glick, B.S. Does Picky Eating Affect Weight-for-Length Measurements in Young Children? Clin. Pediatr. 2009, 49, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruth, B.R.; Ziegler, P.; Gordon, A.; Barr, S.I. Prevalence of Picky Eaters among Infants and Toddlers and Their Caregivers’ Decisions about Offering a New Food. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 104, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.L.; Pesch, M.H.; Perrin, E.M.; Appugliese, D.P.; Miller, A.L.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Lumeng, J.C. Maternal Concern for Child Undereating. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofholz, A.; Schulte, A.; Berge, J.M. How Parents Describe Picky Eating and Its Impact on Family Meals: A Qualitative Analysis. Appetite 2016, 110, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, L.; Coulthard, H.; Williamson, I. The Lived Experience of Parenting a Child with Sensory Sensitivity and Picky Eating. Matern. Child Nutr. 2022, 18, e13330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.M.; Emmett, P. Picky Eating in Children: Causes and Consequences. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 78, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, M.S.; Heo, M.; Keller, K.; Pietrobelli, A. Child Food Neophobia Is Heritable, Associated with Less Compliant Eating, and Moderates Familial Resemblance for BMI. Obesity 2013, 21, 1650–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.C.; Holub, S.C. Maternal Feeding Practices Associated with Food Neophobia. Appetite 2012, 59, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, C.; Lafraire, J.; Picard, D.; Blissett, J. Food Rejection in Young Children: Validation of the Child Food Rejection Scale in English and Cross-Cultural Examination in the UK and France. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 73, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Beltagi, M.; Choueiry, E.; Alahmadi, N.; Demerdash, Z.; Ayesh, W.; Al-Said, K.; Al-Haddad, F.; Shaaban, S.Y.; Tawfik, E. Diet Fortification for Mild and Moderate Picky Eating in Typically Developed Children: Opinion Review of Middle East Consensus. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2024, 14, 101769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, V.; Markowitz, G. Picky Eater or Feeding Disorder? Strategies for Determining the Difference. PubMed 2013, 4, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Steinsbekk, S.; Bonneville-Roussy, A.; Fildes, A.; Llewellyn, C.; Wichstrøm, L. Child and Parent Predictors of Picky Eating from Preschool to School Age. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, B.C.; Dias, P.; Lima, V.S.; Campos, J.; Gonçalves, S. Prevalence and Correlates of Picky Eating in Preschool-Aged Children: A Population-Based Study. Eat. Behav. 2016, 22, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, P.; Ek, A.; Somaraki, M.; Hammar, U.; Eli, K.; Nowicka, P. Picky Eating in Swedish Preschoolers of Different Weight Status: Application of Two New Screening Cut-Offs. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, L.; Bryant-Waugh, R.; Mandy, W.; Solmi, F. Investigating the Prevalence and Risk Factors of Picky Eating in a Birth Cohort Study. Eat. Behav. 2023, 50, 101780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, N.; An, R.; Lee, S.; Donovan, S.M. Correlates of Picky Eating and Food Neophobia in Young Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł-Kozakowska, A.; Piórecka, B.; Schlegel-Zawadzka, M. Prevalence of Food Neophobia in Pre-School Children from Southern Poland and Its Association with Eating Habits, Dietary Intake and Anthropometric Parameters: A Cross-Sectional Study. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 21, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, A.; Golding, J.; Macleod, J.; Lawlor, D.A.; Fraser, A.; Henderson, J.; Molloy, L.; Ness, A.; Ring, S.M.; Smith, G.D. Cohort Profile: The ‘Children of the 90s’—The Index Offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 42, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.; McCaffery, H.; Miller, A.L.; Kaciroti, N.; Lumeng, J.C.; Pesch, M.H. Trajectories of Picky Eating in Low-Income US Children. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20192018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theresa, L.; Mary, T.; Kendra, H.; Heather, J.; Rachel, L.; Sydney, N. Picky Eating and the Associated Nutritional Consequences. J. Food Nutr. Disord. 2017, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljakainen, H.; Figueiredo, R.A.O.; Rounge, T.B.; Weiderpass, E. Picky Eating—A Risk Factor for Underweight in Finnish Preadolescents. Appetite 2018, 133, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, D.V.; Emmett, P.M.; Taylor, C.M. Effect of Being a Persistent Picky Eater on Feeding Difficulties in School-Aged Children. Appetite 2023, 183, 106483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroshko, I.; Brennan, L. Maternal Controlling Feeding Behaviours and Child Eating in Preschool-aged Children. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 70, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, D.Y.T.; Jacob, A. Perception of Picky Eating among Children in Singapore and Its Impact on Caregivers: A Questionnaire Survey. Asia Pac. Fam. Med. 2012, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.; Chang, H. Picky Eating Behaviors Linked to Inappropriate Caregiver–Child Interaction, Caregiver Intervention, and Impaired General Development in Children. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2016, 58, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alkazemi, D.; Zafar, T.A.; Ahmad, G.J. The Association of Picky Eating among Preschoolers in Kuwait with Mothers’ Negative Attitudes and Weight Concerns. Appetite 2025, 208, 107931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; van der Horst, K.; Fries, L.R.; Yu, K.; You, L.; Zhang, Y.; Vinyes-Parès, G.; Wang, P.; Ma, D.; Yang, X.; et al. Perceptions of Food Intake and Weight Status among Parents of Picky Eating Infants and Toddlers in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Appetite 2016, 108, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Lee, E.; Ning, K.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, D.; Gao, H.; Yang, B.; Bai, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y. Prevalence of Picky Eating Behaviour in Chinese School-Age Children and Associations with Anthropometric Parameters and Intelligence Quotient. A Cross-Sectional Study. Appetite 2015, 91, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubler, J.; Wiggins, L.D.; Macias, M.M.; Whitaker, T.M.; Shaw, J.S.; Squires, J.; Pajek, J.A.; Wolf, R.B.; Slaughter, K.; Broughton, A.S.; et al. Evidence-Informed Milestones for Developmental Surveillance Tools. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021052138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiner, C.E.; Knedgen, M.M.; Proctor, K.B.; Zickgraf, H.F. Relation between ARFID Symptomatology and Picky Eating Onset and Duration. Eat. Behav. 2024, 54, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnick, D.L.; Bell, E.M.; Ghassabian, A.; Robinson, S.L.; Sundaram, R.; Yeung, E. Feeding Problems as an Indicator of Developmental Delay in Early Childhood. J. Pediatr. 2021, 242, 184–191.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolk, A. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Waugh, R. Feeding and Eating Disorders in Children. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 42, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hail, L.; Grange, D.L. Bulimia Nervosa in Adolescents: Prevalence and Treatment Challenges. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2018, 11, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, V.; Tavolacci, M.; Bargiacchi, A.; Leblanc, V.; Déchelotte, P.; Stordeur, C.; Bellaïche, M. Analysis of Feeding and Eating Disorders in 191 Children According to Psychiatric or Gastroenterological Recruitment: The PEDIAFED Cohort Study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2024, 32, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zickgraf, H.F.; Ellis, J.M. Initial Validation of the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (NIAS): A Measure of Three Restrictive Eating Patterns. Appetite 2017, 123, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.J.; Lawson, E.A.; Micali, N.; Misra, M.; Deckersbach, T.; Eddy, K.T. Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: A Three-Dimensional Model of Neurobiology with Implications for Etiology and Treatment. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak, A.; Czepczor-Bernat, K.; Modrzejewska, J.; Modrzejewska, A.; Matusik, E.; Matusik, P. Avoidant/Restrictive Food Disorder (ARFID), Food Neophobia, Other Eating-Related Behaviours and Feeding Practices among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and in Non-Clinical Sample: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvers, E.; Erlich, K. Picky Eating or Something More? Dif Ferentiating ARFID from Typical Childhood Development. Nurse Pract. 2023, 48, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goday, P.S.; Huh, S.Y.; Silverman, A.H.; Lukens, C.T.; Dodrill, P.; Cohen, S.S.; Delaney, A.L.; Feuling, M.B.; Noel, R.J.; Gisel, E.G.; et al. Pediatric Feeding Disorder. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 68, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrem, H.; Park, J.; Thoyre, S.M.; McComish, C.; McGlothen-Bell, K. Mapping the Gaps: A Scoping Review of Research on Pediatric Feeding Disorder. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 48, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrem, H.; Pederson, J.; Dodrill, P.; Romeo, C.; Thompson, K.; Thomas, J.J.; Zucker, N.; Noel, R.J.; Zickgraf, H.F.; Menzel, J.E.; et al. A US-Based Consensus on Diagnostic Overlap and Distinction for Pediatric Feeding Disorder and Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 58, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Herle, M.; Fildes, A.; Cooke, L.; Steinsbekk, S.; Llewellyn, C. Food Fussiness and Food Neophobia Share a Common Etiology in Early Childhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 58, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, L.; Haworth, C.M.A.; Wardle, J. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Children’s Food Neophobia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenders, E.A.; Wesseldijk, L.W.; Boomsma, D.I.; Larsen, J.K.; Vink, J.M. Heritability of Adult Picky Eating in the Netherlands. Appetite 2024, 195, 107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Szczepańska, E.; Szymańska, D.; Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Kowalski, O. Neophobia—A Natural Developmental Stage or Feeding Difficulties for Children? Nutrients 2022, 14, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothenberg, M.E. The Immunology That Underlies Picky Eating. Nature 2023, 620, 497–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plum, T.; Binzberger, R.; Thiele, R.; Shang, F.; Postrach, D.; Fung, C.; Fortea, M.; Stakenborg, N.; Wang, Z.; Tappe-Theodor, A.; et al. Mast Cells Link Immune Sensing to Antigen-Avoidance Behaviour. Nature 2023, 620, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florsheim, E.; Bachtel, N.D.; Cullen, J.L.; Lima, B.C.; Godazgar, M.; de Carvalho, F.; Chatain, C.P.; Zimmer, M.R.; Zhang, C.; Gautier, G.; et al. Immune Sensing of Food Allergens Promotes Avoidance Behaviour. Nature 2023, 620, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederkoorn, C.; Jansen, A.; Havermans, R.C. Feel Your Food. The Influence of Tactile Sensitivity on Picky Eating in Children. Appetite 2014, 84, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthmann, J.; Jansen, A.; Havermans, R.C.; Nederkoorn, C.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Roefs, A. Bits and Pieces. Food Texture Influences Food Acceptance in Young Children. Appetite 2014, 84, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaïche, M.; Leblanc, V.; Viala, J.; Jung, C. Oral Exploration and Food Selectivity: A Case-Control Study Conducted in a Multidisciplinary Outpatient Setting. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1115787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennerød, F.F.F.; Nicklaus, S.; Lien, N.; Almli, V.L. The Development of Basic Taste Sensitivity and Preferences in Children. Appetite 2018, 127, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.V.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Hyldig, G. The Importance of Liking of Appearance, -Odour, -Taste and -Texture in the Evaluation of Overall Liking. A Comparison with the Evaluation of Sensory Satisfaction. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 71, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, A.H.; Pick, S.; Lev-Ari, L.; Bachner-Melman, R. A Longitudinal Study of Maternal Feeding and Children’s Picky Eating. Appetite 2020, 154, 104804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohar, A.H.; Lev-Ari, L.; Bachner-Melman, R. Child and Maternal Correlates of Picky Eating in Young Children. Psychology 2019, 10, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, E.; Roefs, A.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Jansen, A.; Gubbels, J.S.; Sleddens, E.F.C.; Thijs, C. Picky Eating and Child Weight Status Development: A Longitudinal Study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 29, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, N.; Musaad, S.; Lee, S.; Donovan, S.M. Home Feeding Environment and Picky Eating Behavior in Preschool-Aged Children: A Prospective Analysis. Eat. Behav. 2018, 30, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.M.; Galloway, A.T.; Webb, R.M.; Martz, D.M.; Farrow, C. Recollections of Pressure to Eat during Childhood, but Not Picky Eating, Predict Young Adult Eating Behavior. Appetite 2015, 97, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Appugliese, D.P.; Miller, A.L.; Lumeng, J.C.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Pesch, M.H. Maternal Prompting Types and Child Vegetable Intake: Exploring the Moderating Role of Picky Eating. Appetite 2019, 146, 104518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutbi, H.A. Picky Eating in School-Aged Children: Sociodemographic Determinants and the Associations with Dietary Intake. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzow, M.; Canfield, C.F.; Gross, R.S.; Messito, M.J.; Cates, C.B.; Weisleder, A.; Johnson, S.B.; Mendelsohn, A.L. Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Perceived Picky Eating in a Low-Income, Primarily Hispanic Sample. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2019, 40, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalçın, S.; Oflu, A.; Akturfan, M.; Yalçın, S.S. Characteristics of Picky Eater Children in Turkey: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galloway, A.T.; Watson, P.; Pitama, S.; Farrow, C. Socioeconomic Position and Picky Eating Behavior Predict Disparate Weight Trajectories in Infancy. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.L.; Perrin, E.M.; Peterson, K.E.; Brophy-Herb, H.E.; Horodynski, M.A.; Contreras, D.; Miller, A.L.; Appugliese, D.P.; Ball, S.; Lumeng, J.C. Association of Picky Eating With Weight Status and Dietary Quality Among Low-Income Preschoolers. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 18, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutbi, H.A. The Relationships between Maternal Feeding Practices and Food Neophobia and Picky Eating. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandstra, N.F.; Huston, P.; Zvonek, K.; Heinz, C.; Piccione, E. Outcomes for Feeding Tube-Dependent Children With Oral Aversion in an Intensive Interdisciplinary Treatment Program. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2020, 63, 2497–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, H.J.; Bakula, D.M.; Wallisch, A.; Romine, R.S.; Fleming, K.; Edwards, S.; Bruce, A.S.; Chang, C.; Mousa, H.; Davis, A.M. Pediatric Tube Weaning: A Meta-Analysis of Factors Contributing to Success. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2023, 30, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmeister, J.D.; Zaborek, N.; Thibeault, S.L. Postextubation Dysphagia in Pediatric Populations: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes. J. Pediatr. 2019, 211, 126–133.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąbik, K.; Patro-Gołąb, B.; Zalewski, B.; Wojtyniak, K.; Ostaszewski, P.; Horvath, A. Infant Feeding Practices and Later Parent-Reported Feeding Difficulties: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 79, 1236–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinat, S.; Mackay, M.; Synnes, A.; Holsti, L.; Zwicker, J.G. Early Feeding Behaviours of Extremely Preterm Infants Predict Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. Early Hum. Dev. 2022, 173, 105647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boswell, N. Complementary Feeding Methods—A Review of the Benefits and Risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.W.; Williams, S.; Fangupo, L.J.; Wheeler, B.J.; Taylor, B.; Daniels, L.; Fleming, E.; McArthur, J.; Morison, B.; Erickson, L.W.; et al. Effect of a Baby-Led Approach to Complementary Feeding on Infant Growth and Overweight. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Kowalski, O. Complementary Feeding Methods, Feeding Problems, Food Neophobia, and Picky Eating among Polish Children. Children 2023, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Ramírez, A.D.; Maneschy, I.; Miguel-Berges, M.L.; Pastor-Villaescusa, B.; Leis, R.; Babio, N.; Navas-Carretero, S.; Portolés, O.; Moreira, A.S.P.; Jurado-Castro, J.M.; et al. Early Feeding Practices and Eating Behaviour in Preschool Children: The CORALS Cohort. Matern. Child Nutr. 2024, 20, e13672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Guthrie, C.A.; Sanderson, S.C.; Rapoport, L. Development of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, M.; Martel, C.; Porporino, M.; Zygmuntowicz, C. The Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale: A Brief Bilingual Screening Tool for Identifying Feeding Problems. Paediatr. Child Health 2011, 16, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llewellyn, C.; van Jaarsveld, C.H.M.; Johnson, L.; Carnell, S.; Wardle, J. Development and Factor Structure of the Baby Eating Behaviour Questionnaire in the Gemini Birth Cohort. Appetite 2011, 57, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanawati, A.A.; McLaren, D.S. Assessment of Marginal Malnutrition. Nature 1970, 228, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant-Waugh, R.; Micali, N.; Cooke, L.; Lawson, E.A.; Eddy, K.T.; Thomas, J.J. Development of the Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview, a Multi-informant, Semi-structured Interview of Feeding Disorders across the Lifespan: A Pilot Study for Ages 10–22. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 52, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, K.; Adams, D.; Alston-Knox, C.; Heussler, H.; Keen, D. Exploring the Sensory Profiles of Children on the Autism Spectrum Using the Short Sensory Profile-2 (SSP-2). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 2069–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiong, T.; Tan, M.L.; Lim, T.; Quak, S.H.; Aw, M.M. Selective Feeding—An Under-Recognised Contributor to Picky Eating. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Vandenplas, Y.; Singendonk, M.; Cabana, M.D.; DiLorenzo, C.; Gottrand, F.; Gupta, S.K.; Langendam, M.; Staiano, A.; Thapar, N.; et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, 516–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.A.; Oliva, S.; Παπαδοπούλου, A.; Thomson, M.; Gutiérrez-Junquera, C.; Kalach, N.; Orel, R.; Auth, M.K.; Nijenhuis-Hendriks, D.; Strisciuglio, C.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children: An Update from the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 79, 394–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Verdú, E.F.; Bai, J.C.; Lionetti, E. Coeliac Disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, M.S.; Shahril, M.R.; Haron, H.; Kadar, M.; Safii, N.S.; Hamzaid, N.H. Interventions for Picky Eaters among Typically Developed Children—A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, K.; Lloyd-Puryear, M.A.; Huntington, K. Nutritional Treatment for Inborn Errors of Metabolism: Indications, Regulations, and Availability of Medical Foods and Dietary Supplements Using Phenylketonuria as an Example. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012, 107, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommel, N.; Meyer, A.D.; Feenstra, L.; Veereman-Wauters, G. The Complexity of Feeding Problems in 700 Infants and Young Children Presenting to a Tertiary Care Institution. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2003, 37, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, M.; Jones, N.; Bontems, P.; Carroll, M.; Czinn, S.J.; Gold, B.D.; Goodman, K.J.; Harris, P.; Jerris, R.; Kalach, N.; et al. Updated Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN Guidelines for Management of Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Children and Adolescents (2023). J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 79, 758–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godny, L.; Dotan, I. Avoiding Food Avoidance in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2023, 11, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, F.; Bouin, M.; D’Aoust, L.; Lemoyne, M.; Presse, N. Food Avoidance in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: What, When and Who? Clin. Nutr. 2017, 37, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehade, M.; Meyer, R.; Beauregard, A. Feeding Difficulties in Children with Non–IgE-Mediated Food Allergic Gastrointestinal Disorders. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 122, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reche-Olmedo, L.; Torres-Collado, L.; Compañ-Gabucio, L.; Hera, M.G. de la The Role of Occupational Therapy in Managing Food Selectivity of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Scoping Review. Children 2021, 8, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilman, L.B.; Meredith, P.; Kennedy-Behr, A.; Campbell, G.; Frakking, T.; Swanepoel, L.; Verdonck, M. Picky Eating in Children: Current Clinical Trends, Practices, and Observations within the Australian Health-care Context. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2023, 70, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilman, L.B.; Meredith, P.; Southon, N.; Kennedy-Behr, A.; Frakking, T.; Swanepoel, L.; Verdonck, M. A Qualitative Inquiry of Parents of Extremely Picky Eaters: Experiences, Strategies and Future Directions. Appetite 2023, 190, 107022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 10 Tips for Parents of Picky Eaters. Available online: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/toddler/nutrition/Pages/Picky-Eaters.aspx (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Chen, J.-L.; Doong, J.-Y.; Tu, M.; Huang, S.-C. Impact of Dietary Coparenting and Parenting Strategies on Picky Eating Behaviors in Young Children. Nutrients 2024, 16, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, C.; Copello, A.; Jones, C.A.; Blissett, J. Children Overcoming Picky Eating (COPE)—A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. Appetite 2020, 154, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskin, A.; Barth, A.; Mansoor, E.; Farias, A.; Rothenberg, W.A.; Garcia, D.; Jent, J. Impact of Parent Child Interaction Therapy on Child Eating Behaviors. Appetite 2024, 200, 107544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.C.; Roberts, L.T.; Musher-Eizenman, D.R. Mindful Feeding: A Pathway between Parenting Style and Child Eating Behaviors. Eat. Behav. 2019, 36, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saati, A.A.; Adly, H.M. Assessing the Correlation between Blood Trace Element Concentrations, Picky Eating Habits, and Intelligence Quotient in School-Aged Children. Children 2023, 10, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, H.; Lu, J.; Yang, C.-Y.; Yeh, P.; Chu, S. Serum Trace Element Levels and Their Correlation with Picky Eating Behavior, Development, and Physical Activity in Early Childhood. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, F.; Yalawar, M.; Suryawanshi, P.; Ghosh, A.; Jog, P.; Khadilkar, A.; Kishore, B.; Paruchuri, A.K.; Pote, P.D.; Ravi, M.D.; et al. Effect of Oral Nutritional Supplementation on Adequacy of Nutrient Intake among Picky-Eating Children at Nutritional Risk in India: A Randomized Double Blind Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira-de-Almeida, C.A.; Ciampo, L.A.D.; Martínez, E.Z.; Contini, A.A.; Nogueira-de-Almeida, M.E.; Ferraz, I.S.; Epifânio, M.; Ued, F.d.V. Clinical Evolution of Preschool Picky Eater Children Receiving Oral Nutritional Supplementation during Six Months: A Prospective Controlled Clinical Trial. Children 2023, 10, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwańska, J.; Pskit, Ł.; Stróżyk, A.; Horvath, A.; Statuch, S.; Szajewska, H. Effect of Oral Nutritional Supplements Administration on the Management of Children with Picky Eating and Underweight: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 67, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Kishore, B.; Shaikh, I.A.; Satyavrat, V.; Kumar, A.; Shah, T.; Pote, P.; Shinde, S.; Berde, Y.; Low, Y.L.; et al. Effect of Oral Nutritional Supplementation on Growth and Recurrent Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in Picky Eating Children at Nutritional Risk: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 2186–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronica, S.-W.M. How Picky Eating Becomes an Illness—Marketing Nutrient-Enriched Formula Milk in a Chinese Society. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2016, 56, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, R.; Turriziani, L.; Suraniti, S.; Graziano, M.; Patanè, S.; Randazzo, A.; Passantino, C.; Cara, M.D.; Quartarone, A.; Cucinotta, F. Case Report: Multicomponent Intervention for Severe Food Selectivity in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Single Case Study. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1455356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.-R.; Kwon, J.; Yi, S.; Kim, E. Sensory Based Feeding Intervention for Toddlers With Food Refusal: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 45, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoen, S.; Balderrama, R.; Dopheide, E.; Harris, A.; Hoffman, L.; Sasse, S. Methodological Components for Evaluating Intervention Effectiveness of SOS Feeding Approach: A Feasibility Study. Children 2025, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, H.; Williamson, I.; Palfreyman, Z.; Lyttle, S. Evaluation of a Pilot Sensory Play Intervention to Increase Fruit Acceptance in Preschool Children. Appetite 2017, 120, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nederkoorn, C.; Theiβen, J.; Tummers, M.; Roefs, A. Taste the Feeling or Feel the Tasting: Tactile Exposure to Food Texture Promotes Food Acceptance. Appetite 2017, 120, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.; Kennedy, O.; Hill, C.; Houston-Price, C. Peas, Please! Food Familiarization through Picture Books Helps Parents Introduce Vegetables into Preschoolers’ Diets. Appetite 2018, 128, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, C.; Lafraire, J.; Picard, D. Visual Exposure and Categorization Performance Positively Influence 3- to 6-Year-Old Children’s Willingness to Taste Unfamiliar Vegetables. Appetite 2017, 120, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rompay, T.J.L.; Kramer, L.-M.; Saakes, D. The Sweetest Punch: Effects of 3D-Printed Surface Textures and Graphic Design on Ice-Cream Evaluation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Cox, S.; Swenny, C.; Mogren, C.; Walbert, L.; Fraker, C. Food Chaining: A Systematic Approach for the Treatment of Children With Feeding Aversion. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2006, 21, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, É.; Jansen, A.; Duker, P.C.; Seys, D.M.; Broers, N.J.; Mulkens, S. Feeding/Eating Problems in Children: Who Does (Not) Benefit after Behavior Therapy? A Retrospective Chart Review. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1108185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.L.; Schaaf, E.B.V.; Cohen, G.M.; Irby, M.B.; Skelton, J.A. Association of Picky Eating and Food Neophobia with Weight: A Systematic Review. Child. Obes. 2016, 12, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, R.; Irwin, C.; Rigby, R.R.; Byrne, R.; Love, P.; Khan, F.; Larach, C.; Yang, W.Y.; Mandalika, S.; Knight-Agarwal, C.R.; et al. Association Between Picky Eating, Weight Status, Vegetable, and Fruit Intake in Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child. Obes. 2024, 20, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, P.K.; Hohman, E.E.; Marini, M.E.; Savage, J.S.; Birch, L.L. Girls’ Picky Eating in Childhood Is Associated with Normal Weight Status from Ages 5 to 15 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1577–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.M.; Northstone, K.; Wernimont, S.M.; Emmett, P. Macro- and Micronutrient Intakes in Picky Eaters: A Cause for Concern? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandvik, P.; Ek, A.; Eli, K.; Somaraki, M.; Bottai, M.; Nowicka, P. Picky Eating in an Obesity Intervention for Preschool-Aged Children—What Role Does It Play, and Does the Measurement Instrument Matter? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Horst, K.; Deming, D.M.; Lesniauskas, R.; Carr, B.T.; Reidy, K. Picky Eating: Associations with Child Eating Characteristics and Food Intake. Appetite 2016, 103, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tine, M.L.V.; McNicholas, F.; Safer, D.L.; Agras, W.S. Follow-up of Selective Eaters from Childhood to Adulthood. Eat. Behav. 2017, 26, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, M.H.; Bauer, K.W.; Christoph, M.J.; Larson, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Young Adult Nutrition and Weight Correlates of Picky Eating during Childhood. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 23, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereboom, J.; Thijs, C.; Eussen, S.J.P.M.; Mommers, M.; Gubbels, J.S. Association of Picky Eating around Age 4 with Dietary Intake and Weight Status in Early Adulthood: A 14-Year Follow-up Based on the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Appetite 2023, 188, 106762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzlose, R.F.; Hennefield, L.; Hoyniak, C.P.; Luby, J.L.; Gilbert, K. Picky Eating in Childhood: Associations With Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 47, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolstenholme, H.; Kelly, C.; Hennessy, M.; Heary, C. Childhood Fussy/Picky Eating Behaviours: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, N.; Copeland, W.; Franz, L.; Carpenter, K.L.H.; Keeling, L.A.; Angold, A.; Egger, H.L. Psychological and Psychosocial Impairment in Preschoolers With Selective Eating. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e582–e590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zickgraf, H.F.; Elkins, A.R. Sensory Sensitivity Mediates the Relationship between Anxiety and Picky Eating in Children/ Adolescents Ages 8–17, and in College Undergraduates: A Replication and Age-Upward Extension. Appetite 2018, 128, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foinant, D.; Lafraire, J.; Thibaut, J. Relationships between Executive Functions and Food Rejection Dispositions in Young Children. Appetite 2022, 176, 106102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gent, V.; Marshall, J.; Weir, K.A.; Trembath, D. Caregiver Perspectives Regarding the Impact of Feeding Difficulties on Mealtime Participation for Primary School-Aged Autistic Children and Their Families. Int. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2025, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, L.E.; Gosliner, W.; Olarte, D.A.; Zuercher, M.D.; Ritchie, L.D.; Orta-Aleman, D.; Schwartz, M.B.; Polacsek, M.; Hecht, C.E.; Hecht, K.; et al. Impact of Mealtime Social Experiences on Student Consumption of Meals at School: A Qualitative Analysis of Caregiver Perspectives. Public Health Nutr. 2025, 28, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Picky Eating (PE) | Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) | Pediatric Feeding Disorder (PFD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Developmentally influenced selective eating with preference for limited foods | DSM-5 disorder characterized by restrictive intake due to sensory factors, fear of aversive consequences, or lack of interest | WHO 2019: Impairment in medical, nutritional, feeding skill, or psychosocial domains |

| Key Characteristics | Rejects familiar and unfamiliar foods; often improves with age | Restricted intake + significant weight/nutritional impairment | Feeding difficulties lasting ≥2 weeks with functional impact |

| Psychosocial Impact | Mild–moderate, family stress | Significant, often requiring multidisciplinary intervention | Significant; often overlaps with ARFID |

| Prevalence | 13–50% | 3–5% in pediatric population | 5–25% depending on population |

| Red Flags | Limited variety but adequate growth | Weight loss, nutritional deficiencies, dependence on supplements | Medical instability, dysphagia, oral-motor impairment |

| Category | Description | Impact on Feeding |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic | Heritability of neophobia and taste sensitivity | Shapes preference for sweet/bitter, increases selectivity |

| Immune/Neuroimmune | Allergy-driven aversion pathways (IL-4, IgE, GDF15) | Conditioned aversion to foods causing immune activation |

| Sensory Processing | Over-responsivity to taste, texture, smell | Strong aversion to non-preferred sensory properties |

| Temperament | Negative emotionality, shyness | Heightened refusal, more mealtime conflict |

| Family Environment | Pressure, restriction, parental anxiety | Reinforces maladaptive feeding patterns |

| Early Feeding Experiences | Tube feeding, medical trauma, delayed oral exposure | Long-term oral aversion, narrowed diet |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pjetraj, D.; Pjetraj, A.; Sayed, D.; Severini, M.; Falcioni, L.; Svarca, L.E.; Gatti, S.; Lionetti, M.E. Decoding Picky Eating in Children: A Temporary Phase or a Hidden Health Concern? Nutrients 2025, 17, 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243884

Pjetraj D, Pjetraj A, Sayed D, Severini M, Falcioni L, Svarca LE, Gatti S, Lionetti ME. Decoding Picky Eating in Children: A Temporary Phase or a Hidden Health Concern? Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243884

Chicago/Turabian StylePjetraj, Dorina, Amarildo Pjetraj, Dalia Sayed, Michele Severini, Ludovica Falcioni, Lucia Emanuela Svarca, Simona Gatti, and Maria Elena Lionetti. 2025. "Decoding Picky Eating in Children: A Temporary Phase or a Hidden Health Concern?" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243884

APA StylePjetraj, D., Pjetraj, A., Sayed, D., Severini, M., Falcioni, L., Svarca, L. E., Gatti, S., & Lionetti, M. E. (2025). Decoding Picky Eating in Children: A Temporary Phase or a Hidden Health Concern? Nutrients, 17(24), 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243884