Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strain 06CC2 Attenuates Fat Accumulation and Modulates the Gut Microbiota in a Mouse Model of Early-Stage Diet-Induced Obesity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of LP06CC2

2.2. Experimental Animals and Dietary Intervention Protocol

2.3. Feeding Termination and Biological Sample Collection

2.4. Biochemical Analysis of Plasma and Liver Samples

2.5. Histological Evaluation of Adipose and Liver Tissues

2.6. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.7. Microbiota Analysis via 16S Ribosomal Ribonucleic Acid Sequencing

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physiological Parameters and Tissue Masses

3.2. Plasma and Hepatic Lipid Profiles

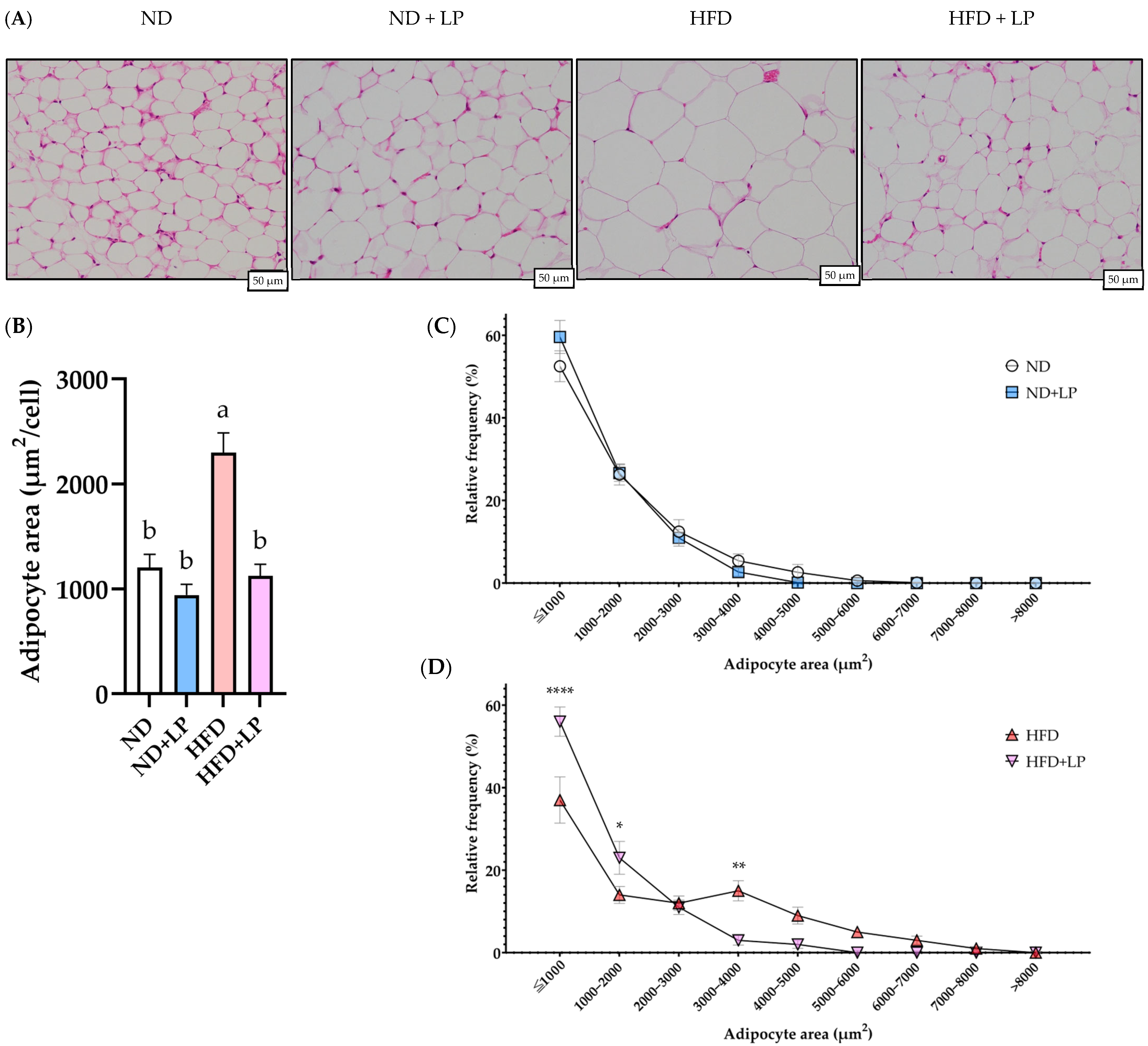

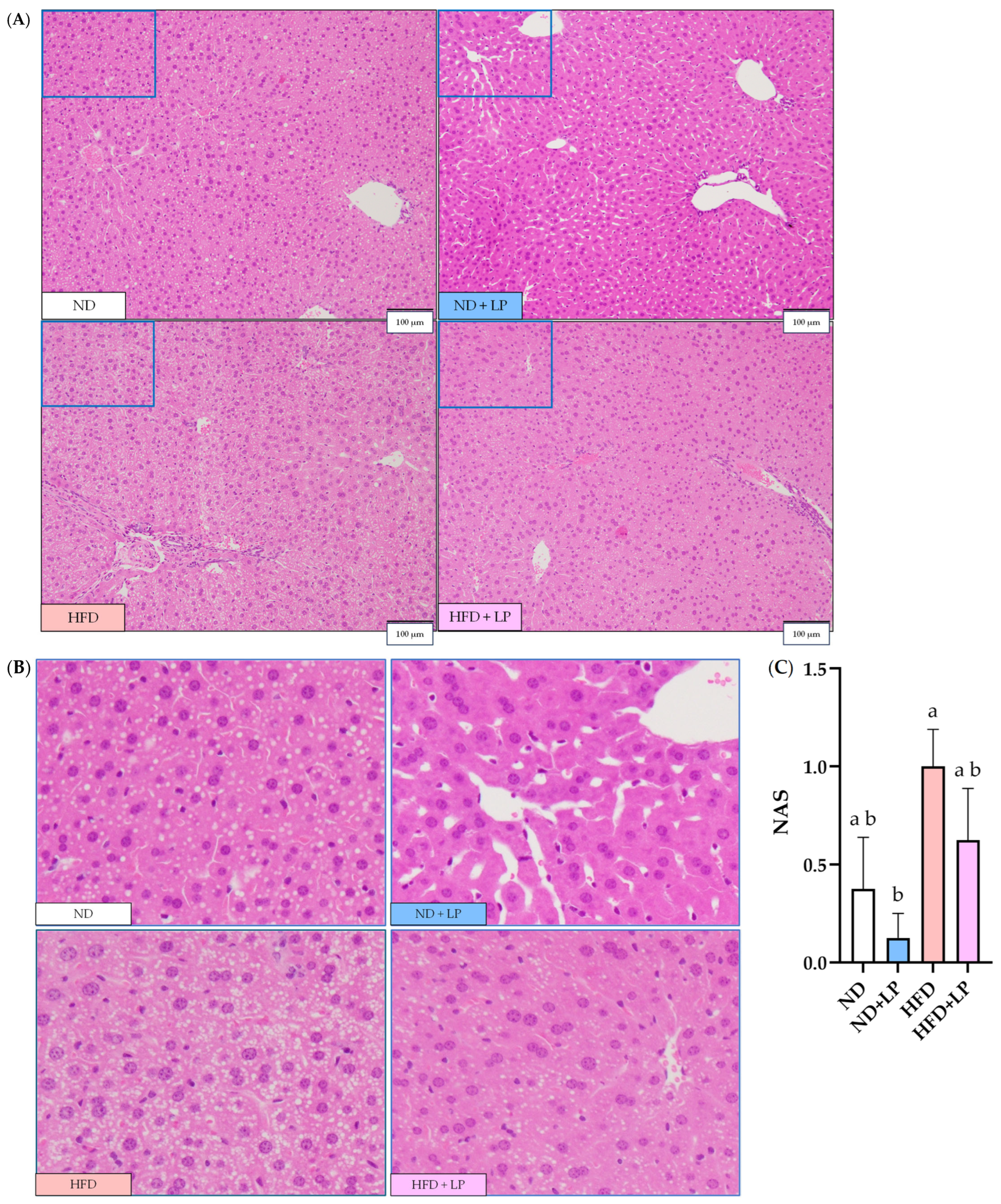

3.3. Histopathological Changes in the Epididymal Fat and Liver

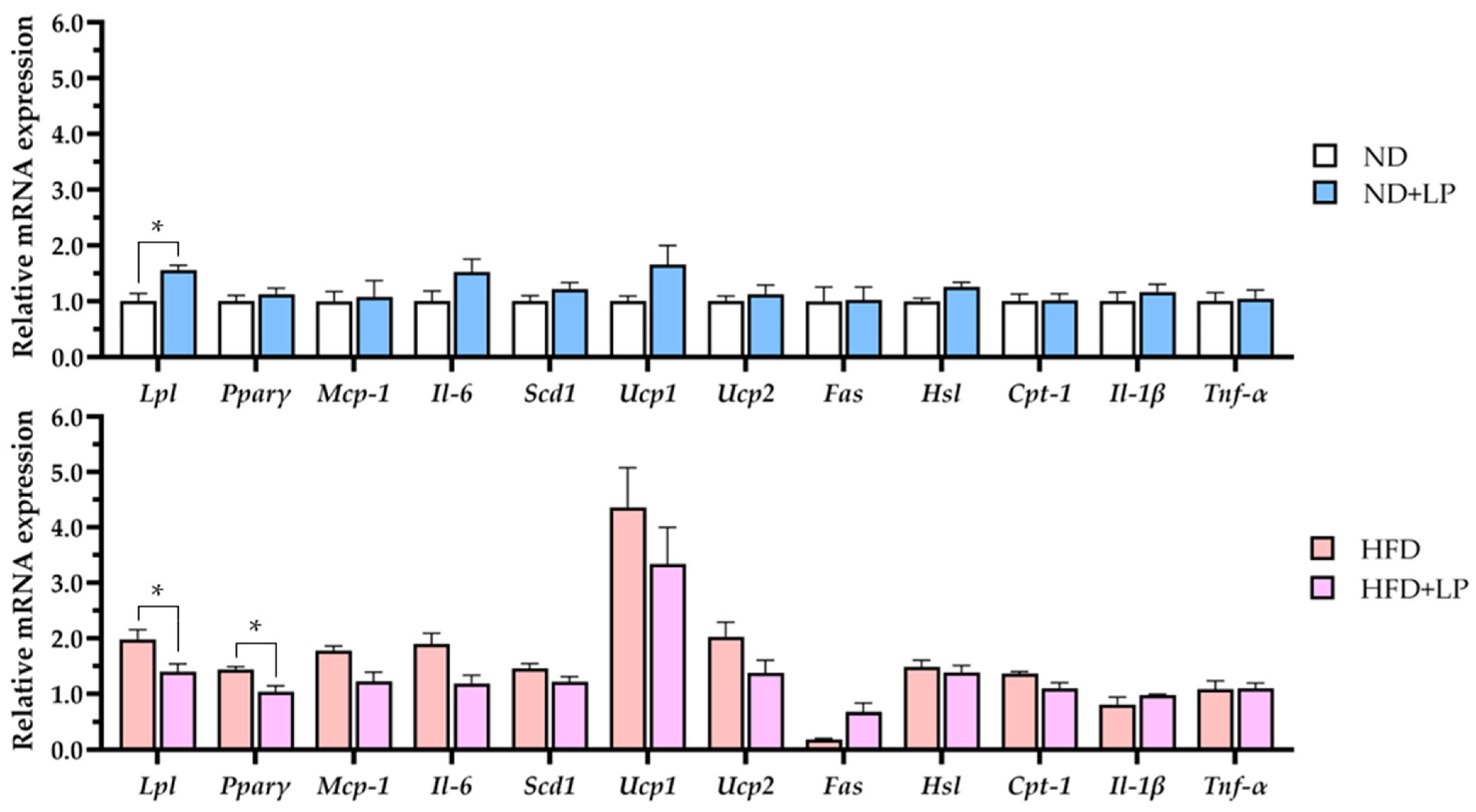

3.4. Modulation of Lipid Metabolism-Related Gene Expression in Epididymal Fat by Diet and LP06CC2 Treatment

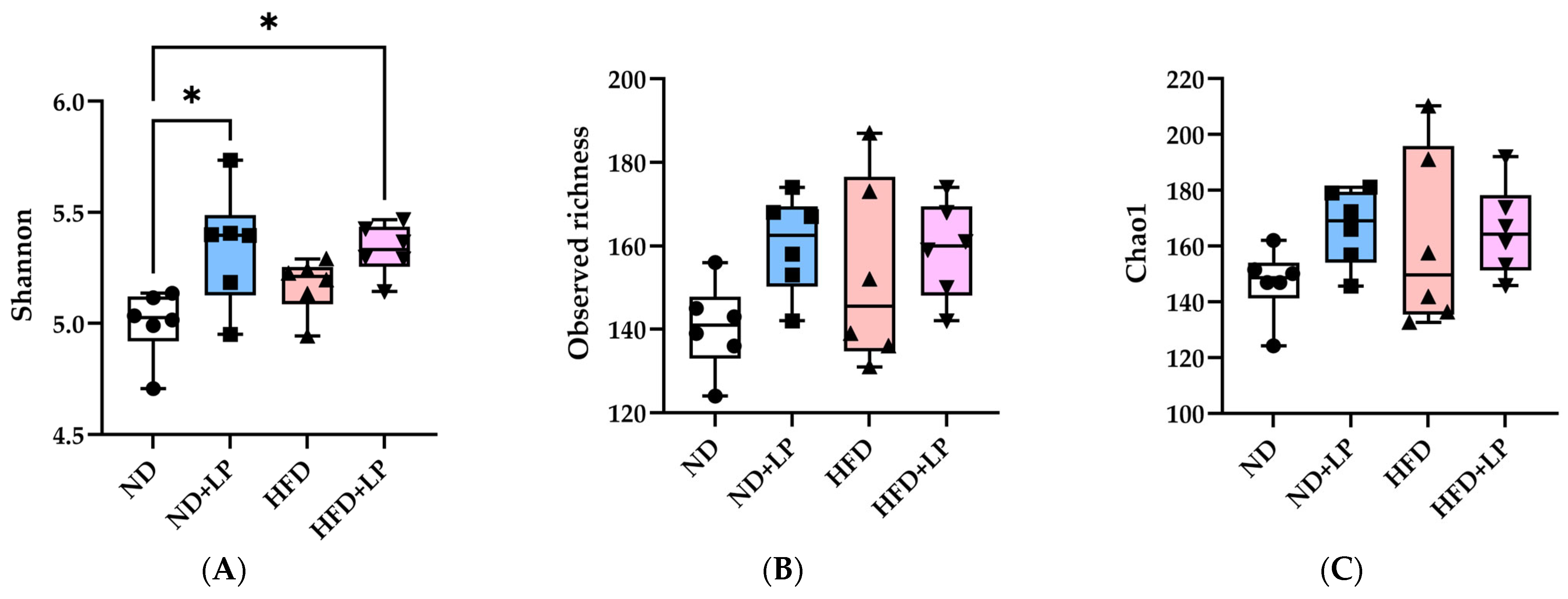

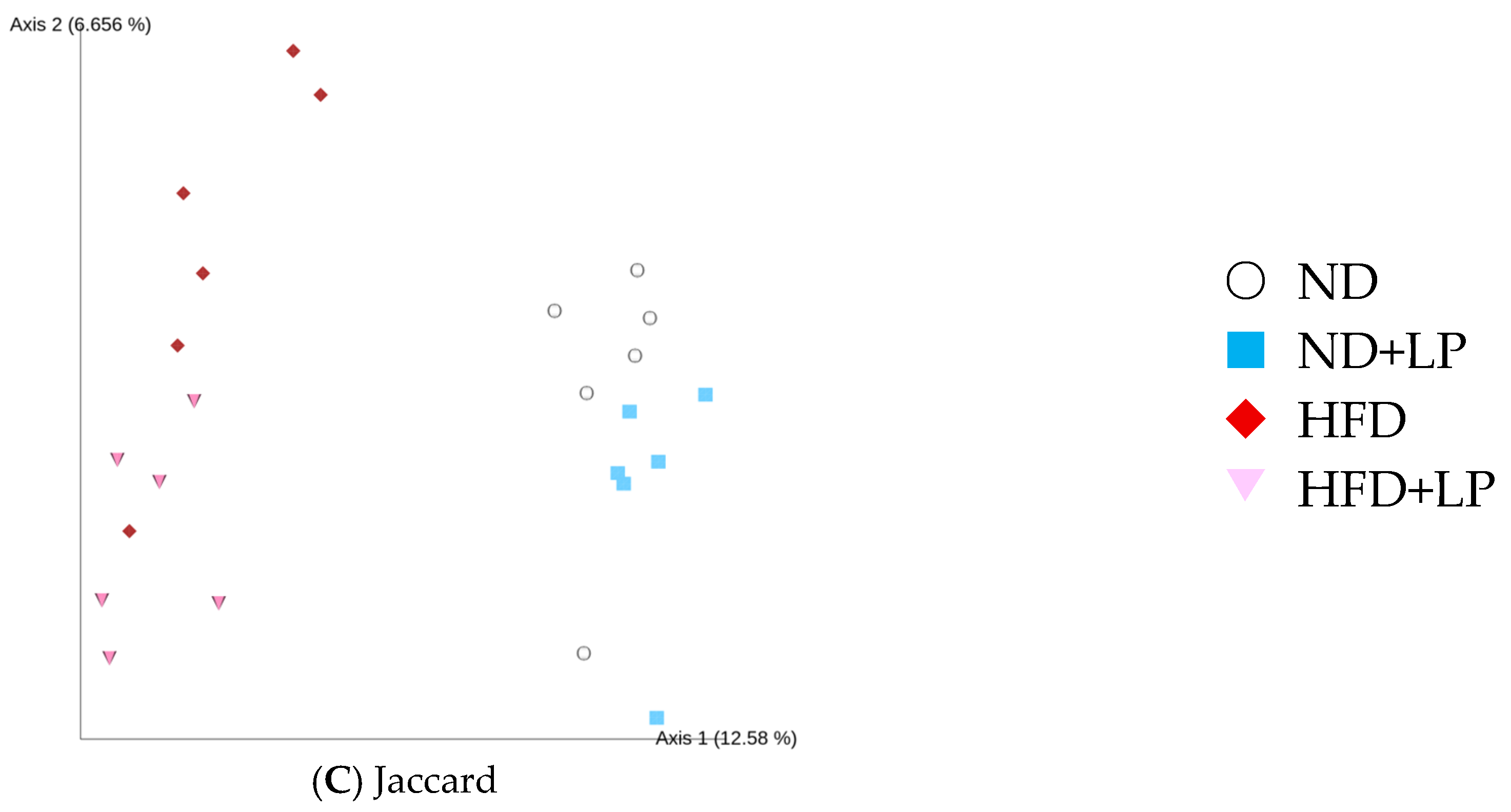

3.5. Changes in Fecal Microbiota in Response to Diet and LP06CC2 Treatment

3.6. Correlation Between Epididymal Fat Parameters and Fecal Microbiota According to Diet and LP06CC2 Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Bluher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—A global public health perspective. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delzenne, N.M.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Backhed, F.; Cani, P.D. Targeting gut microbiota in obesity: Effects of prebiotics and probiotics. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011, 7, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.J.; Santos, A.; Prada, P.O. Linking gut microbiota and inflammation to obesity and insulin resistance. Physiology 2016, 31, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Shen, H. Microbes in Health and Disease: Human Gut Microbiota. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D.; Bibiloni, R.; Knauf, C.; Waget, A.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Burcelin, R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 2006, 444, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Liu, X. Modulatory effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on chronic metabolic diseases. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpi, F.M.; Coman, M.M.; Silvi, S.; Picciolini, M.; Verdenelli, M.C.; Napolioni, V. Comprehensive pan-genome analysis of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum complete genomes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Echegaray, N.; Yilmaz, B.; Sharma, H.; Kumar, M.; Pateiro, M.; Ozogul, F.; Lorenzo, J.M. A novel approach to Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: From probiotic properties to the omics insights. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 268, 127289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, B.; Bangar, S.P.; Echegaray, N.; Suri, S.; Tomasevic, I.; Manuel Lorenzo, J.; Melekoglu, E.; Rocha, J.M.; Ozogul, F. The Impacts of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on the Functional Properties of Fermented Foods: A Review of Current Knowledge. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takeda, S.; Yamasaki, K.; TAkeshita, M.; Kikuchi, Y.; Tsend-Ayush, C.; Dashnyam, B.; Ahhmed, A.M.; Kawahara, S.; Muguruma, M. The investigation of probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Mongolian dairy products. Anim. Sci. J. 2011, 82, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Kanmura, S.; Morinaga, Y.; Kawabata, K.; Arima, S.; Sasaki, F.; Nasu, Y.; Tanoue, S.; Hashimoto, S.; Takeshit, M.; et al. Oral administration of Lactobacillus plantarum 06CC2 prevents experimental colitis in mice via an anti-inflammatory response. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yamasaki, M.; Minesaki, M.; Iwakiri, A.; Miyamoto, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Nishiyama, K.; Tsend-Ayush, C.; Oyunsuren, T.; Li, Y.; Nakano, T.; et al. Lactobacillus plantarum 06CC2 reduces hepatic cholesterol levels and modulates bile acid deconjugation in Balb/c mice fed a high-cholesterol diet. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 6164–6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nei, S.; Matsusaki, T.; Kawakubo, H.; Ogawa, K.; Nishiyama, K.; Tsend-Ayush, C.; Nakano, T.; Takeshita, M.; Shinyama, T.; Yamasaki, M. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 06CC2 Enhanced the Expression of Intestinal Uric Acid Excretion Transporter in Mice. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yamasaki, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Nishiyama, K.; Tsend-Ayush, C.; Li, Y.; Matsusaki, T.; Nakano, T.; Takeshita, M.; Arima, Y. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 06CC2 upregulates intestinal ZO-1 protein and bile acid metabolism in Balb/c mice fed high-fat diet. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2024, 43, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, L.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A.; et al. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Tomita, J.; Nishioka, K.; Hisada, T.; Nishijima, M. Development of a prokaryotic universal primer for simultaneous analysis of Bacteria and Archaea using next-generation sequencing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0252-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Molano, L.-A.G.; Vega-Abellaneda, S.; Manichanh, C. GSR-DB: A manually curated and optimized taxonomical database for 16S rRNA amplicon analysis. mSystems 2024, 9, e0095023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chao, A. Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand. J. Stat. 1984, 11, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.; Lladser, M.E.; Knights, D.; Stombaugh, J.; Knight, R. UniFrac: An effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J. 2011, 5, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, P. The distribution of the flora in the alpine zone. N. Phytol. 1912, 11, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhou, X.R.; Chu, L.L.; Ran, W.T.; Tan, F.; Zhao, X. Regulating effect of Lactobacillus plantarum CQPC03 on lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemura, N.; Okubo, T.; Sonoyama, K. Lactobacillus plantarum strain No. 14 reduces adipocyte size in mice fed high-fat diet. Exp. Biol. Med. 2010, 235, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siersbæk, M.S.; Ditzel, N.; Hejbøl, E.K.; Præstholm, S.M.; Markussen, L.K.; Avolio, F.; Li, L.; Lehtonen, L.; Hansen, A.K.; Schrøder, H.D.; et al. C57BL/6J substrain differences in response to high-fat diet intervention. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L. High fat diet induced obesity model using four strains of mice: Kunming, C57BL/6, BALB/c and ICR. Exp. Anim. 2020, 69, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Okubo, T.; Takemura, N.; Yoshida, A.; Sonoyama, K. KK/Ta Mice Administered Lactobacillus plantarum Strain No. 14 Have Lower Adiposity and Higher Insulin Sensitivity. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2013, 32, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sakai, T.; Taki, T.; Nakamoto, A.; Shuto, E.; Tsutsumi, R.; Toshimitsu, T.; Makino, S.; Ikegami, S. Lactobacillus plantarum OLL2712 regulates glucose metabolism in C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat diet. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2013, 59, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.J.; Dong, H.J.; Jeong, H.U.; Ryu, D.W.; Song, S.M.; Kim, Y.R.; Jung, H.H.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, Y.H. Lactobacillus plantarum LMT1-48 exerts anti-obesity effect in high-fat diet-induced obese mice by regulating expression of lipogenic genes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, C.C.; Weng, W.L.; Lai, W.L.; Tsai, H.P.; Liu, W.H.; Lee, M.H.; Tsai, Y.C. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum Strain K21 on High-Fat Diet-Fed Obese Mice. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 391767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cai, H.; Wen, Z.; Li, X.; Meng, K.; Yang, P. Lactobacillus plantarum FRT10 alleviated high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice through regulating the PPARα signal pathway and gut microbiota. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 5959–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, F.M.; Chui, P.C.; Antonellis, P.J.; Bina, H.A.; Kharitonenkov, A.; Flier, J.S.; Maratos-Flier, E. Obesity is a fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21)-resistant state. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2781–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Torrez Lamberti, M.F.; Thompson, S.; Harrison, N.A.; Gardner, C.L.; da Silva, D.R.; Teixeira, L.D.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Gonzalez, C.F.; Chukkapalli, S.S.; Lorca, G.L. Lactobacillus johnsonii N6.2 improves glycemia and reduces diabetes-induced organ injury in the db/db mice model. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 267, e250184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Rodríguez, A.M.; Beresford, T. Bile salt hydrolase and lipase inhibitory activity in reconstituted skim milk fermented with lactic acid bacteria. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 77, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Fu, Q.; Jiang, H.M.; Shen, M.; Zhao, R.L.; Qian, Y.; He, Y.Q.; Xu, K.F.; Xu, X.Y.; Chen, H.; et al. Temporal metabolic and transcriptomic characteristics crossing islets and liver reveal dynamic pathophysiology in diet-induced diabetes. iScience 2021, 24, 102265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Varghese, J.; James, J.V.; Anand, R.; Narayanasamy, M.; Rebekah, G.; Ramakrishna, B.; Nellickal, A.J.; Jacob, M. Development of insulin resistance preceded major changes in iron homeostasis in mice fed a high-fat diet. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 84, 108441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, Y.S.; Park, E.J.; Park, G.S.; Ko, S.H.; Park, J.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, D.; Kang, J.; Lee, H.J. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ATG-K2 Exerts an Anti-Obesity Effect in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice by Modulating the Gut Microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, J.; Jang, J.Y.; Kwon, M.S.; Lim, S.K.; Kim, N.; Lee, J.; Park, H.K.; Yun, M.; Shin, M.Y.; Jo, H.E.; et al. Mixture of Two Lactobacillus plantarum Strains Modulates the Gut Microbiota Structure and Regulatory T Cell Response in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, D.W.; He, Y.; Reitman, M.L. Genomic organization and regulation by dietary fat of the uncoupling protein 3 and 2 genes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 256, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surwit, R.S.; Wang, S.; Petro, A.E.; Sanchis, D.; Raimbault, S.; Ricquier, D.; Collins, S. Diet-induced changes in uncoupling proteins in obesity-prone and obesity-resistant strains of mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 4061–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fromme, T.; Klingenspor, M. Uncoupling protein 1 expression and high-fat diets. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 300, R1–R8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; Huang, J.; Yu, T.; Guan, X.; Sun, M.; Zhao, D.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Q. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum BXM2 Treatment Alleviates Disorders Induced by a High-Fat Diet in Mice by Improving Intestinal Health and Modulating the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2025, 17, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Werlinger, P.; Nguyen, H.T.; Gu, M.; Cho, J.H.; Cheng, J.; Suh, J.W. Lactobacillus reuteri MJM60668 Prevent Progression of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease through Anti-Adipogenesis and Anti-inflammatory Pathway. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hou, S.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, P.; Yang, H.; He, H.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Jin, T.; Liu, Z.; et al. Supplementation of mixed Lactobacillus alleviates metabolic impairment, inflammation, and dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in an obese mouse model. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1554996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vacca, M.; Celano, G.; Calabrese, F.M.; Portincasa, P.; Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M. The Controversial Role of Human Gut Lachnospiraceae. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabot, S.; Membrez, M.; Blancher, F.; Berger, B.; Moine, D.; Krause, L.; Bibiloni, R.; Bruneau, A.; Gérard, P.; Siddharth, J.; et al. High fat diet drives obesity regardless the composition of gut microbiota in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakova, I.; Smirnova, Y.; Gryaznova, M.; Syromyatnikov, M.; Chizhkov, P.; Popov, E.; Popov, V. The Effect of Short-Term Consumption of Lactic Acid Bacteria on the Gut Microbiota in Obese People. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khateeb, S.; Albalawi, A.; Alkhedaide, A. Diosgenin Modulates Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2022, 15, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Woo, G.H.; Kwon, T.-H.; Jeon, J.-H. Obesity-Driven Metabolic Disorders: The Interplay of Inflammation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component (g/kg) | ND | ND + LP | HFD | HFD + LP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | 200 | 200 | 187 | 187 |

| Corn starch | 529.5 | 528.5 | 212.5 | 211.5 |

| Sucrose | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Soybean oil | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Lard | 0 | 0 | 330 | 330 |

| Cellulose | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Choline bitartrate | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| L-Cystine | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mineral mix | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Vitamin mix | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| tert-Butylhydroquinone | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| LP06CC2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| ND | ND + LP | HFD | HFD + LP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final body weight (g) | 27.80 ± 0.82 | 29.00 ± 0.87 | 30.20 ± 0.78 | 29.70 ± 0.91 |

| Food intake (g/day) | 4.57 ± 0.07 a | 4.62 ± 0.11 a | 2.53 ± 0.06 b | 2.64 ± 0.06 b |

| Calorie intake (kcal/day) | 18.40 ± 0.25 a | 18.20 ± 0.42 a | 14.20 ± 0.34 b | 14.80 ± 0.33 b |

| (mg/g Body Weight) | ND | ND + LP | HFD | HFD + LP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 30.40 ± 0.59 | 30.40 ± 0.98 | 27.50 ± 0.97 | 27.10 ± 1.01 |

| Small intestine | 20.70 ± 1.70 | 21.10 ± 1.61 | 20.70 ± 0.76 | 21.00 ± 0.97 |

| Cecum | 8.95 ± 1.75 | 7.26 ± 0.64 | 5.97 ± 0.62 | 6.17 ± 0.45 |

| Large intestine | 4.83 ± 0.69 | 3.80 ± 0.15 | 5.25 ± 1.08 | 4.10 ± 0.15 |

| Epididymal fat | 16.90 ± 2.37 ac | 13.80 ± 2.08 a | 29.70 ± 4.26 b | 25.60 ± 3.83 bc |

| Perirenal fat | 2.91 ± 0.59 ab | 1.79 ± 0.53 b | 3.88 ± 0.72 a | 3.24 ± 0.81 ab |

| ND | ND + LP | HFD | HFD + LP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 132.60 ± 10.60 | 122.90 ± 9.40 | 122.90 ± 5.53 | 107.70 ± 6.50 |

| TGs (mg/dL) | 15.50 ± 1.89 | 14.30 ± 1.85 | 16.60 ± 2.13 | 13.30 ± 1.22 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 65.50 ± 4.20 | 72.30 ± 2.80 | 57.80 ± 3.08 | 63.60 ± 2.50 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 47.10 ± 1.58 | 47.90 ± 1.08 | 47.10 ± 3.36 | 46.60 ± 3.12 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 2.00 ± 0.00 ab | 1.63 ± 0.18 b | 2.50 ± 0.27 a | 1.88 ± 0.13 ab |

| HDL-C/LDL-C | 23.60 ± 0.79 | 30.80 ± 4.51 | 20.30 ± 2.35 | 26.30 ± 3.35 |

| NEFA (µEq/dL) | 790.30 ± 67.70a | 824.10 ± 87.2 ab | 1013.60 ± 69.40 b | 994.40 ± 66.50 b |

| AST (IU/L) | 85.70 ± 12.40 | 92.90 ± 13.00 | 72.30 ± 3.40 | 82.30 ± 6.85 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 15.70 ± 1.21 | 16.90 ± 1.24 | 17.90 ± 0.58 | 18.40 ± 1.80 |

| UA (mg/dL) | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 0.90 ± 0.10 | 0.91 ± 0.12 | 0.84 ± 0.05 |

| TBA (µmol/L) | 1.29 ± 0.18 | 1.43 ± 0.30 | 14.50 ± 8.79 | 7.71 ± 6.38 |

| FGF21 (pg/mL) | 115.60 ± 33.20 a | 675.50 ± 268.40 b | 531.90 ± 111.20 b | 777.40 ± 331.30 ab |

| Liver | ||||

| TGs (mg/g) | 13.47 ± 1.37 | 12.10 ± 0.94 | 16.94 ± 2.91 | 12.88 ± 1.09 |

| TC (mg/g) | 6.33 ± 0.13 | 6.53 ± 0.14 | 6.59 ± 0.16 | 6.84 ± 0.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matsusaki, T.; Takakura, C.; Ichitani, K.; Tsend-Ayush, C.; Kataoka, H.; Fukushima, T.; Kurogi, J.; Nishiyama, K.; Ogawa, K.; Shinyama, T.; et al. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strain 06CC2 Attenuates Fat Accumulation and Modulates the Gut Microbiota in a Mouse Model of Early-Stage Diet-Induced Obesity. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3855. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243855

Matsusaki T, Takakura C, Ichitani K, Tsend-Ayush C, Kataoka H, Fukushima T, Kurogi J, Nishiyama K, Ogawa K, Shinyama T, et al. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strain 06CC2 Attenuates Fat Accumulation and Modulates the Gut Microbiota in a Mouse Model of Early-Stage Diet-Induced Obesity. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3855. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243855

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatsusaki, Tatsuya, Chisato Takakura, Kaho Ichitani, Chuluunbat Tsend-Ayush, Hiroaki Kataoka, Tsuyoshi Fukushima, Junko Kurogi, Kazuo Nishiyama, Kenjirou Ogawa, Takuo Shinyama, and et al. 2025. "Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strain 06CC2 Attenuates Fat Accumulation and Modulates the Gut Microbiota in a Mouse Model of Early-Stage Diet-Induced Obesity" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3855. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243855

APA StyleMatsusaki, T., Takakura, C., Ichitani, K., Tsend-Ayush, C., Kataoka, H., Fukushima, T., Kurogi, J., Nishiyama, K., Ogawa, K., Shinyama, T., Nakano, T., & Yamasaki, M. (2025). Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strain 06CC2 Attenuates Fat Accumulation and Modulates the Gut Microbiota in a Mouse Model of Early-Stage Diet-Induced Obesity. Nutrients, 17(24), 3855. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243855