Effects of Caffeine Dose and Administration Method on Time-Trial Performance: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

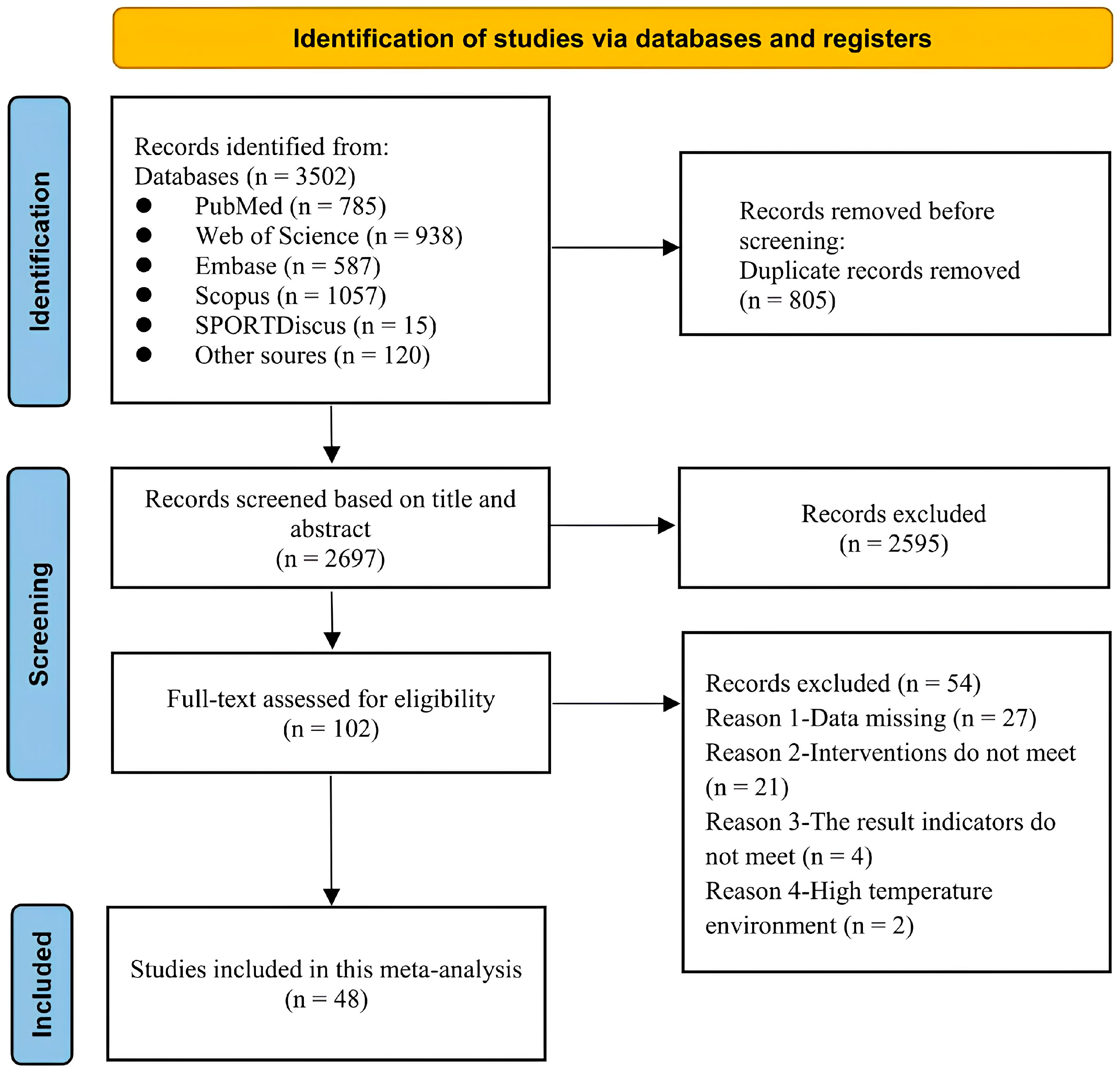

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Risk of Bias

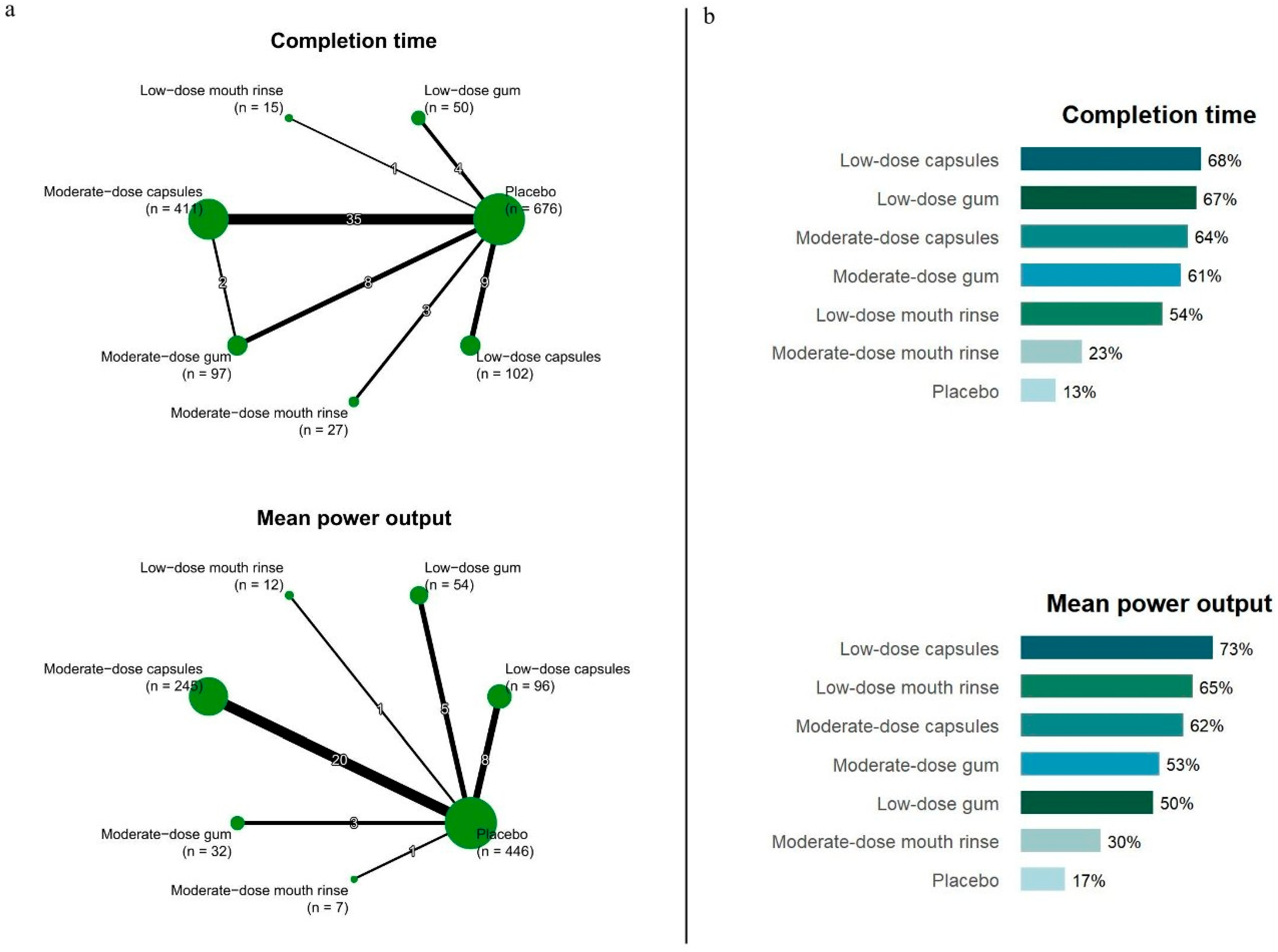

3.3. Network Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Practical Implications

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doherty, M.; Smith, P.M. Effects of caffeine ingestion on exercise testing: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2004, 14, 626–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganio, M.S.; Klau, J.F.; Casa, D.J.; Armstrong, L.E.; Maresh, C.M. Effect of caffeine on sport-specific endurance performance: A systematic review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J. Exploring the minimum ergogenic dose of caffeine on resistance exercise performance: A meta-analytic approach. Nutrition 2022, 97, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya-González, J.; Rendo-Urteaga, T.; Domínguez, R.; Castillo, D.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Grgic, J. Acute Effects of Caffeine Supplementation on Movement Velocity in Resistance Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Silva, J.P.; Choo, H.C.; Franchini, E.; Abbiss, C.R. Isolated ingestion of caffeine and sodium bicarbonate on repeated sprint performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, A.; Garriga-Alonso, L.; Montalvo-Alonso, J.J.; Val-Manzano, M.D.; Valades, D.; Vila, H.; Ferragut, C. Sex differences in the acute effect of caffeine on repeated sprint performance: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2025, 25, e12233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Coso, J.; Muñoz, G.; Muñoz-Guerra, J. Prevalence of caffeine use in elite athletes following its removal from the World Anti-Doping Agency list of banned substances. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Schabort, E.J.; Hawley, J.A. Reliability of power in physical performance tests. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ding, L.; Qin, Q.; Lei, T.H.; Girard, O.; Cao, Y. Effect of caffeine ingestion on time trial performance in cyclists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2024, 21, 2363789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilding, A.E.; Overton, C.; Gleave, J. Effects of caffeine, sodium bicarbonate, and their combined ingestion on high-intensity cycling performance. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2012, 22, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinlivan, A.; Irwin, C.; Grant, G.D.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Skinner, T.; Leveritt, M.; Desbrow, B. The effects of Red Bull energy drink compared with caffeine on cycling time-trial performance. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.L.; Sim, M.; Landers, G.; Peeling, P. A comparison of caffeine versus pseudoephedrine on cycling time-trial performance. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2013, 23, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, G.; Loureiro, L.M.R.; Reis, C.E.G.; Saunders, B. Effects of caffeine chewing gum supplementation on exercise performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalley, P.J.; Dearing, C.G.; Paton, C.D. The Effects of Different Forms of Caffeine Supplement on 5-km Running Performance. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2020, 15, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Liu, J.; Yao, Y.; Guo, L.; Chen, B.; Cao, Y.; Girard, O. Caffeinated chewing gum enhances maximal strength and muscular endurance during bench press and back squat exercises in resistance-trained men. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1540552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, A.; Shaw, C.; Sorsby, A.C.; Ashworth, P.; Hanif, F.; Williams, C.E.; Ranchordas, M.K. Caffeine gum improves 5 km running performance in recreational runners completing parkrun events. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, T.L.; Jenkins, D.G.; Coombes, J.S.; Taaffe, D.R.; Leveritt, M.D. Dose response of caffeine on 2000-m rowing performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, M.P.; O’Brien, B.J.; Knez, W.L.; Paton, C.D. Caffeine has a small effect on 5-km running performance of well-trained and recreational runners. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2008, 11, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, J.; Bottoms, L. The Effects of Carbohydrate and Caffeine Mouth Rinsing on Arm Crank Time-Trial Performance. J. Sports Res. 2014, 1, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottoms, L.; Hurst, H.; Scriven, A.; Lynch, F.; Bolton, J.; Vercoe, L.; Shone, Z.; Barry, G.; Sinclair, J.K. The effect of caffeine mouth rinse on self-paced cycling performance. Comp. Exerc. Physiol. 2014, 10, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, B.; Salanti, G.; Caldwell, D.M.; Chaimani, A.; Schmid, C.H.; Cameron, C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Straus, S.; Thorlund, K.; Jansen, J.P.; et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: Checklist and explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2023. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Spriet, L.L. Exercise and sport performance with low doses of caffeine. Sports Med. 2014, 44 (Suppl. S2), S175–S184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southward, K.; Rutherfurd-Markwick, K.J.; Ali, A. The Effect of Acute Caffeine Ingestion on Endurance Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1913–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, A.; Kocić, M.; Trajković, N.; Popa, C.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A.; Padulo, J. Acute Effects of Caffeine on Overall Performance in Basketball Players-A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevon, D.; Fursa, S.R.; Malcolm, A.L. Intercoder Reliability and Validity of WebPlotDigitizer in Extracting Graphed Data. Behav. Modif. 2017, 41, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efthimiou, O.; Debray, T.P.; van Valkenhoef, G.; Trelle, S.; Panayidou, K.; Moons, K.G.; Reitsma, J.B.; Shang, A.; Salanti, G. GetReal in network meta-analysis: A review of the methodology. Res. Synth. Methods 2016, 7, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rücker, G. Network meta-analysis, electrical networks and graph theory. Res. Synth. Methods 2012, 3, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Bujkiewicz, S.; Law, M.; Riley, R.D.; White, I.R. A matrix-based method of moments for fitting multivariate network meta-analysis models with multiple outcomes and random inconsistency effects. Biometrics 2018, 74, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. Resolve conflicting rankings of outcomes in network meta-analysis: Partial ordering of treatments. Res. Synth. Methods 2017, 8, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.; White, I.R.; Riley, R.D. Quantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analyses. Stat. Med. 2012, 31, 3805–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahn, U.; Binder, H.; König, J. A graphical tool for locating inconsistency in network meta-analyses. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimori, G.H.; Karyekar, C.S.; Otterstetter, R.; Cox, D.S.; Balkin, T.J.; Belenky, G.L.; Eddington, N.D. The rate of absorption and relative bioavailability of caffeine administered in chewing gum versus capsules to normal healthy volunteers. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 234, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalley, P.; Paton, C.; Dearing, C.G. Caffeine metabolites are associated with different forms of caffeine supplementation and with perceived exertion during endurance exercise. Biol. Sport 2021, 38, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boat, R.; Williamson, O.; Read, J.; Jeong, Y.H.; Cooper, S.B. Self-control exertion and caffeine mouth rinsing: Effects on cycling time-trial performance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 53, 101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doering, T.M.; Fell, J.W.; Leveritt, M.D.; Desbrow, B.; Shing, C.M. The effect of a caffeinated mouth-rinse on endurance cycling time-trial performance. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, N.; Queiroz, M.; Felício, F.P.; Ferreira, J.; Gerosa-Neto, J.; Mota, J.F.; da Silva, C.R.; Ghedini, P.C.; Saunders, B.; Pimentel, G.D. Acute caffeine mouth rinsing does not improve 10-km running performance in CYP1A2 C-allele carriers. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 42, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesniak, A.Y.; Davis, S.E.; Moir, G.L.; Sauers, E.J. The effects of carbohydrate, caffeine, and combined rinses on cycling performance. J. Sport Hum. Perform. 2016, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, C. Are caffeine’s performance-enhancing effects partially driven by its bitter taste? Med. Hypotheses 2019, 131, 109301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, S.; Tan, M.; Guelfi, K.J.; Fournier, P.A. Mouth rinsing with a bitter solution without ingestion does not improve sprint cycling performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 115, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, R.; McDonald, K.; Hurst, P.; Pickering, C. Can taste be ergogenic? Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marticorena, F.M.; Carvalho, A.; Oliveira, L.F.; Dolan, E.; Gualano, B.; Swinton, P.; Saunders, B. Nonplacebo Controls to Determine the Magnitude of Ergogenic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 1766–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredholm, B.B. Adenosine actions and adenosine receptors after 1 week treatment with caffeine. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1982, 115, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikodijević, O.; Jacobson, K.A.; Daly, J.W. Locomotor activity in mice during chronic treatment with caffeine and withdrawal. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1993, 44, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, B.; Ruiz-Moreno, C.; Salinero, J.J.; Del Coso, J. Time course of tolerance to the performance benefits of caffeine. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, R.; Cordery, P.; Funnell, M.; Mears, S.; James, L.; Watson, P. Chronic ingestion of a low dose of caffeine induces tolerance to the performance benefits of caffeine. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 1920–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, P.M.; Shirai, Y.; Ritz, C.; Nordsborg, N.B. Caffeine and Bicarbonate for Speed. A Meta-Analysis of Legal Supplements Potential for Improving Intense Endurance Exercise Performance. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris 2024 Olympic Games—Cycling Road—Men’s Individual Time Trial Results. Available online: https://www.olympics.com/zh/olympic-games/paris-2024/results/cycling-road/men-individual-time-trial (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Abernethy, D.R.; Todd, E.L. Impairment of caffeine clearance by chronic use of low-dose oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1985, 28, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.G.; Kang, J.H.; Park, C.S.; Cho, M.H.; Cha, Y.N. Effect of age and smoking on in vivo CYP1A2, flavin-containing monooxygenase, and xanthine oxidase activities in Koreans: Determination by caffeine metabolism. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 67, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, B.; Szabo, A. Placebo and Nocebo Effects on Sports and Exercise Performance: A Systematic Literature Review Update. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Saito, T.; Klosterhoff, R.; de Oliveira, L.F.; Barreto, G.; Perim, P.; Pinto, A.J.; Lima, F.; de Sá Pinto, A.L.; Gualano, B. “I put it in my head that the supplement would help me”: Open-placebo improves exercise performance in female cyclists. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, L. Caffeine and the Elderly. Drugs Aging 1998, 13, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.L.; Liu, X.; Yang, M.Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Yin, F.Q.; Zhang, Z.T.; Zhang, C. Association between caffeine intake and fat free mass index: A retrospective cohort study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2025, 22, 2445607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Palmer, A.A.; de Wit, H. Genetics of caffeine consumption and responses to caffeine. Psychopharmacology 2010, 211, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domaszewski, P.; Konieczny, M.; Pakosz, P.; Matuska, J.; Poliwoda, A.; Skorupska, E.; Santafe, M. Body fat percentage is a key factor in elevated plasma levels of caffeine and its metabolite in women. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachse, C.; Brockmöller, J.; Bauer, S.; Roots, I. Functional significance of a C→A polymorphism in intron 1 of the cytochrome P450 CYP1A2 gene tested with caffeine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999, 47, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghotbi, R.; Christensen, M.; Roh, H.K.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Aklillu, E.; Bertilsson, L. Comparisons of CYP1A2 genetic polymorphisms, enzyme activity and the genotype-phenotype relationship in Swedes and Koreans. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 63, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, N.; Ghotbi, R.; Jankovic, S.; Aklillu, E. Induction of CYP1A2 by heavy coffee consumption is associated with the CYP1A2-163C>A polymorphism. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 66, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Completion Time | ||||||

| Low-dose capsules | −0.34 (−0.62, −0.06) | |||||

| 0.00 (−0.48, 0.48) | Low-dose gum | −0.34 (−0.74, 0.05) | ||||

| −0.03 (−0.34, 0.28) | −0.03 (−0.45, 0.39) | Moderate-dose capsules | −0.00 (−0.52, 0.51) | −0.31 (−0.44, −0.17) | ||

| −0.05 (−0.43, 0.34) | −0.05 (−0.53, 0.43) | −0.01 (−0.31, 0.28) | Moderate-dose gum | −0.28 (−0.57, −0.01) | ||

| −0.08 (−0.85, 0.69) | −0.08 (−0.90, 0.74) | −0.05 (−0.78, 0.68) | −0.03 (−0.80, 0.73) | Low-dose mouth rinse | −0.26 (−0.98, 0.46) | |

| −0.34 (−0.94, 0.26) | −0.34 (−1.00, 0.33) | −0.31 (−0.86, 0.25) | −0.29 (−0.89, 0.31) | −0.26 (−1.15, 0.64) | Moderate-dose mouth rinse | −0.00 (−0.54, 0.53) |

| −0.34 (−0.62, −0.06) | −0.34 (−0.74, 0.05) | −0.31 (−0.45, −0.17) | −0.30 (−0.57, −0.02) | −0.26 (−0.98, 0.46) | −0.00 (−0.54, 0.53) | Placebo |

| Mean power output | ||||||

| Low-dose capsules | 0.38 (0.09, 0.67) | |||||

| −0.01 (−0.86, 0.85) | Low-dose mouth rinse | 0.39 (−0.42, 1.19) | ||||

| 0.08 (−0.26, 0.42) | 0.09 (−0.74, 0.91) | Moderate-dose capsules | 0.30 (0.12, 0.48) | |||

| 0.14 (−0.43, 0.71) | 0.15 (−0.80, 1.09) | 0.06 (−0.47, 0.58) | Moderate-dose gum | 0.24 (−0.25, 0.73) | ||

| 0.16 (−0.32, 0.63) | 0.16 (−0.73, 1.05) | 0.08 (−0.34, 0.49) | 0.02 (−0.60, 0.64) | Low-dose gum | 0.22 (−0.15, 0.60) | |

| 0.43 (−0.65, 1.52) | 0.44 (−0.88, 1.76) | 0.35 (−0.71, 1.41) | 0.29 (−0.86, 1.45) | 0.28 (−0.84, 1.39) | Moderate-dose mouth rinse | −0.05 (−1.10, 1.00) |

| 0.38 (0.09, 0.67) | 0.39 (−0.42, 1.19) | 0.30 (0.12, 0.48) | 0.24 (−0.25, 0.73) | 0.22 (−0.15, 0.60) | −0.05 (−1.10, 1.00) | Placebo |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, R.; Huang, J.; Chen, B.; Ding, L.; Guo, L.; Cao, Y.; Girard, O. Effects of Caffeine Dose and Administration Method on Time-Trial Performance: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3792. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233792

Xue R, Huang J, Chen B, Ding L, Guo L, Cao Y, Girard O. Effects of Caffeine Dose and Administration Method on Time-Trial Performance: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3792. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233792

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Ruiguo, Jin Huang, Bin Chen, Li Ding, Li Guo, Yinhang Cao, and Olivier Girard. 2025. "Effects of Caffeine Dose and Administration Method on Time-Trial Performance: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3792. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233792

APA StyleXue, R., Huang, J., Chen, B., Ding, L., Guo, L., Cao, Y., & Girard, O. (2025). Effects of Caffeine Dose and Administration Method on Time-Trial Performance: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 17(23), 3792. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233792