Ocular Manifestations of Celiac Disease: Current Evidence and Clinical Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- (a)

- studies conducted in experimental animals or in vitro;

- (b)

- publications not reporting ophthalmic outcomes;

- (c)

- studies without a confirmed CD diagnosis or with insufficient diagnostic criteria;

- (d)

- duplicate datasets;

- (e)

- non-original publications (editorials, commentaries, conference abstracts without full data);

- (f)

- non-English full texts or studies where the full text was not available.

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.4. Critical Appraisal

3. Results

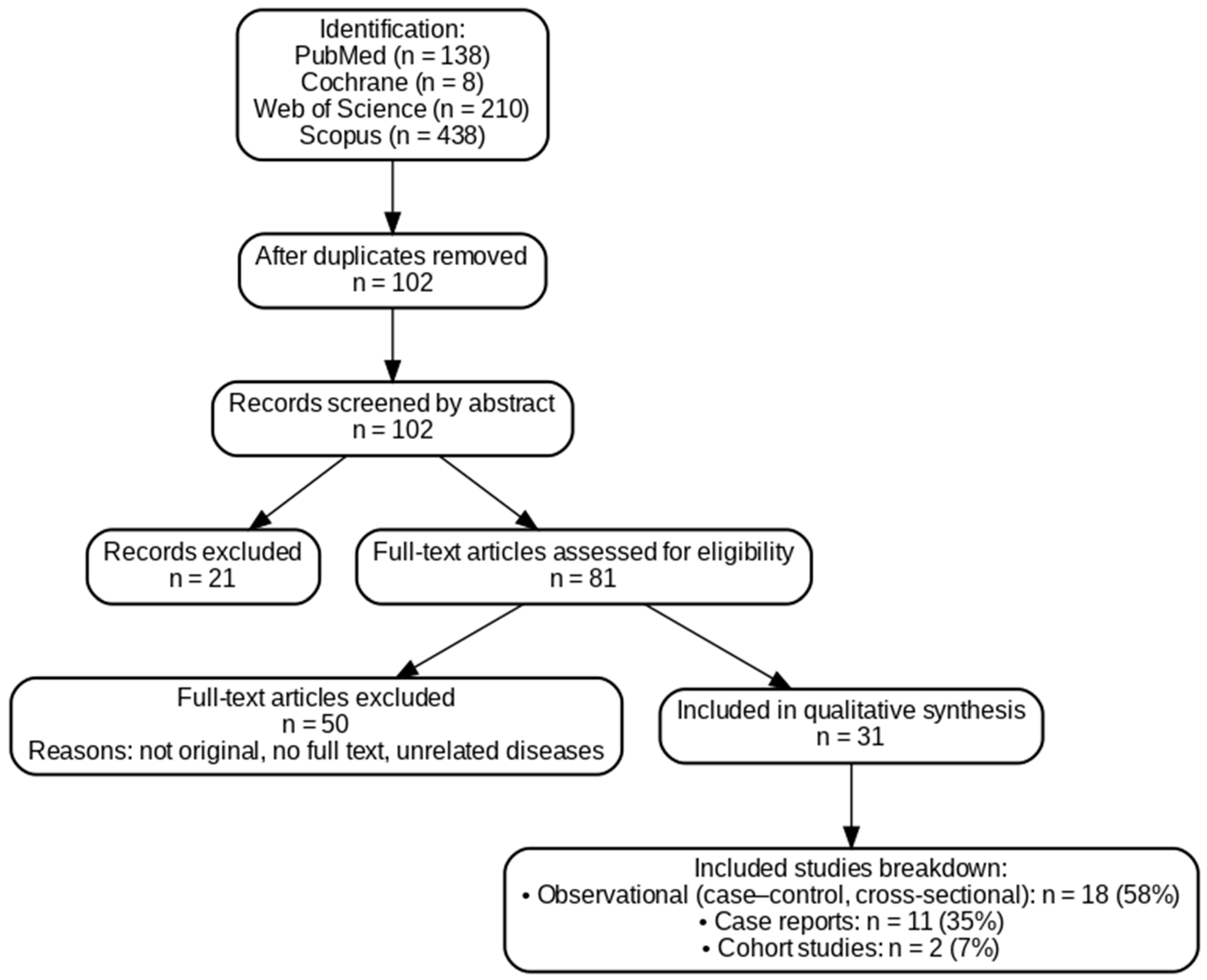

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Characteristic of Inculded Studies

3.3. Summary of Findings from Included Studies

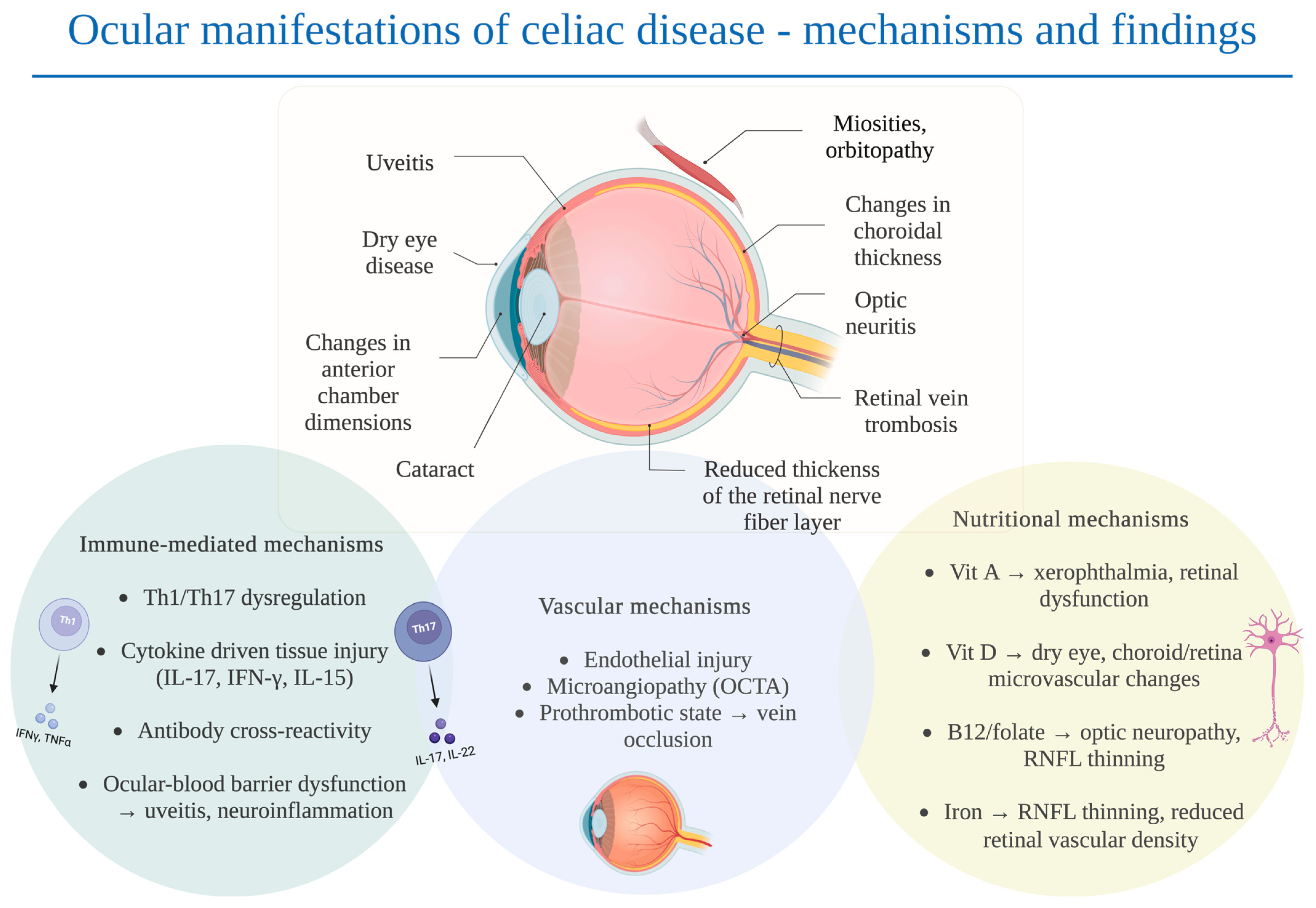

4. Discussion

4.1. Immunological Mechanisms

4.2. Nutritional Mechanisms and Gut Barrier Dysfunction

4.3. Vascular Mechanisms

4.4. Limitations of the Study

4.5. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Practical Recommendations for Clinicians

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Celiac disease |

| GFD | Gluten-free diet |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| OCTA | Optical coherence tomography angiography |

| RNFL | Retinal nerve fiber layer |

| TBUT | Tear break-up time |

| SD-OCT | Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography |

| EDI-OCT | Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography |

| GCC | Ganglion cell complex |

| FAZ | Foveal avascular zone |

| CRVO | Central retinal vein occlusion |

| VD | Vascular density |

References

- Lebwohl, B.; Sanders, D.S.; Green, P.H.R. Coeliac Disease. Lancet 2018, 391, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Arora, A.; Strand, T.A.; Leffler, D.A.; Catassi, C.; Green, P.H.; Kelly, C.P.; Ahuja, V.; Makharia, G.K. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo, M.; Koskimaa, S.; Paavola, S.; Kurppa, K. Serological Testing for Celiac Disease in Children. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 19, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jericho, H.; Sansotta, N.; Guandalini, S. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Celiac Disease: Effectiveness of the Gluten-Free Diet. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaflarska-Popławska, A.; Dolińska, A.; Kuśmierek, M. Nutritional Imbalances in Polish Children with Coeliac Disease on a Strict Gluten-Free Diet. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, G.; Villa, M.P.; Conti, L.; Ranucci, G.; Pacchiarotti, C.; Principessa, L.; Raucci, U.; Parisi, P. Nutritional Deficiencies in Children with Celiac Disease Resulting from a Gluten-Free Diet: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, M.; Dolinsek, J.; Castillejo, G.; Donat, E.; Riznik, P.; Roca, M.; Valitutti, F.; Veenvliet, A.; Mearin, M.L. Follow-up Practices for Children and Adolescents with Celiac Disease: Results of an International Survey. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl, B.; Green, P.H.R.; Söderling, J.; Roelstraete, B.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Association Between Celiac Disease and Mortality Risk in a Swedish Population. JAMA 2020, 323, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caio, G.; Volta, U.; Sapone, A.; Leffler, D.A.; De Giorgio, R.; Catassi, C.; Fasano, A. Celiac Disease: A Comprehensive Current Review. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Leffler, D.A.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Fasano, A.; Green, P.H.R.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Kelly, C.P.; Leonard, J.N.; et al. The Oslo Definitions for Coeliac Disease and Related Terms. Gut 2013, 62, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jericho, H.; Guandalini, S. Extra-Intestinal Manifestation of Celiac Disease in Children. Nutrients 2018, 10, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez Castro, P.; Harkin, G.; Hussey, M.; Christopher, B.; Kiat, C.; Liong Chin, J.; Trimble, V.; McNamara, D.; MacMathuna, P.; Egan, B.; et al. Changes in Presentation of Celiac Disease in Ireland from the 1960s to 2015. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 864–871.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volta, U.; Caio, G.; Stanghellini, V.; De Giorgio, R. The Changing Clinical Profile of Celiac Disease: A 15-Year Experience (1998–2012) in an Italian Referral Center. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fousekis, F.S.; Katsanos, A.; Katsanos, K.H.; Christodoulou, D.K. Ocular Manifestations in Celiac Disease: An Overview. Int. Ophthalmol. 2020, 40, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Martins, T.G.; de Azevedo Costa, A.L.F.; Oyamada, M.K.; Schor, P.; Sipahi, A.M. Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Celiac Disease. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujosevic, S.; Parra, M.M.; Hartnett, M.E.; O’Toole, L.; Nuzzi, A.; Limoli, C.; Villani, E.; Nucci, P. Optical Coherence Tomography as Retinal Imaging Biomarker of Neuroinflammation/Neurodegeneration in Systemic Disorders in Adults and Children. Eye 2022, 37, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, M.; Esteban-Ortega, M.d.M.; Muñoz-Fernández, S. Choroidal and Retinal Thickness in Systemic Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases: A Review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2019, 64, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumus, M.; Eker, S.; Karakucuk, Y.; Ergani, A.C.; Emiroglu, H.H. Retinal and Choroidal Vascular Changes in Newly Diagnosed Celiac Disease: An Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Study. Indian. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 866–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, B.; Sahin, Y. Impact of Adherence to Gluten-Free Diet in Paediatric Celiac Patients on Optical Coherence Tomography Findings: Ocular Imaging Based Study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 42, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dereci, S.; Asik, A.; Direkci, I.; Karadag, A.S.; Hizli, S. Evaluation of Eye Involvement in Paediatric Celiac Disease Patients. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Pachón, S.; Perilla-Soto, S.; Ruiz-Sarmiento, K.; Niño-García, J.A.; Sánchez-Rosso, M.J.; Ordóñez-Caro, M.C.; Camacho-Páez, D.S.; García-Lozada, D. Prevalence of Ocular Manifestations of Vitamin A Deficiency in Children: A Systematic Review. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2025, 100, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Y. Vitamin D Deficiency Is Associated with Dry Eye Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020, 98, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jue, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yuen, V.L.; Chan, O.D.S.; Yam, J.C. Association between Vitamin D Level and Cataract: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2025, 263, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, T.; Dulkadiroglu, R.; Yilmaz, M.; Polat, O.A.; Gunes, A. Evaluation of Macular, Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer and Choroidal Thickness by Optical Coherence Tomography in Children and Adolescents with Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Int. Ophthalmol. 2021, 41, 2399–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Ghasemi, A.; Khorasani, S.; Zare, S.; Sazgar, A.K.; Nikkhah, H. Characteristics of Optical Coherence Tomography in Patients with Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollazadegan, K.; Kugelberg, M.; Tallstedt, L.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Increased Risk of Uveitis in Coeliac Disease: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 96, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krifa, F.; Knani, L.; Sakly, W.; Ghedira, I.; Essoussi, A.S.; Boukadida, J.; Ben Hadj Hamida, F. Uveitis Responding on Gluten Free Diet in a Girl with Celiac Disease and Diabetes Mellitus Type 1. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 2010, 34, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klack, K.; Pereira, R.M.R.; De Carvalho, J.F. Uveitis in Celiac Disease with an Excellent Response to Gluten-Free Diet: Third Case Described. Rheumatol. Int. 2011, 31, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milstein, Y.; Haiimov, E.; Slae, M.; Davidovics, Z.; Millman, P.; Birimberg-Schwartz, L.; Benson, A.; Wilschanski, M.; Amer, R. Increased Risk of Celiac Disease in Patients with Uveitis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2023, 32, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzel, M.M.; Citirik, M.; Kekilli, M.; Cicek, P. Local Ocular Surface Parameters in Patients with Systemic Celiac Disease. Eye 2017, 31, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe Hashas, A.S.; Altunel, O.; Sevınc, E.; Duru, N.; Alabay, B.; Torun, Y.A. The Eyes of Children with Celiac Disease. J. AAPOS 2017, 21, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazar, L.; Oyur, G.; Atay, K. Evaluation of Ocular Parameters in Adult Patients with Celiac Disease. Curr. Eye Res. 2021, 46, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodžić, N.; Banjari, I.; Mušanović, Z.; Nadarević-Vodenčarević, A.; Pilavdžić, A.; Kurtćehajić, A. Accidental Exposure to Gluten Is Linked with More Severe Dry Eye Disease in Celiac Disease Patients on a Gluten-Free Diet. New Armen. Med. J. 2024, 18, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardo, M.; Vitiello, L.; Gagliardi, M.; Capasso, L.; Rosa, N.; Ciacci, C. Ocular Anterior Segment and Corneal Parameters Evaluation in Celiac Disease. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, H.; Saraswathi, S.; Al-Jarrah, B.; Petropoulos, I.N.; Ponirakis, G.; Khan, A.; Singh, P.; Khodor, S.A.; Elawad, M.; Almasri, W.; et al. Corneal Confocal Microscopy Demonstrates Minimal Evidence of Distal Neuropathy in Children with Celiac Disease. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, I.; Yaprak, L.; Yaprak, A.; Akbulut, U. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Findings of Retinal Vascular Structures in Children with Celiac Disease. J. AAPOS 2022, 26, e1–e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, G.; Şen, S.; Çavdar, E.; Mayalı, H.; Cengiz Özyurt, B.; Kurt, E.; Kasırga, E. Should We Worry about the Eyes of Celiac Patients? Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 30, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolukbasi, S.; Erden, B.; Cakir, A.; Bayat, A.H.; Elcioglu, M.N.; Yurttaser Ocak, S.; Gokden, Y.; Adas, M.; Asik, Z.N. Pachychoroid Pigment Epitheliopathy and Choroidal Thickness Changes in Coeliac Disease. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 2019, 6924191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardo, M.; Vitiello, L.; Battipaglia, M.; Mascolo, F.; Iovino, C.; Capasso, L.; Ciacci, C.; Rosa, N. Choroidal Structural Evaluation in Celiac Disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, R.; Dhami, A.; Malhi, N.; Soni, A.; Dhami, G. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion Revealing Celiac Disease: The First Report of Two Cases from India. Indian. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 66, 1315–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoubeidi, H.; Ben Salem, T.; Ben Ghorbel, I.; Houman, M.H. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion Revealing Coeliac Disease. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2016, 3, 000492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Pulido, J.S. Nonischemic Central Retinal Vein Occlusion Associated with Celiac Disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2005, 80, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, S.; Ucmak, F.; Karahan, M.; Ava, S.; Dursun, M.E.; Dursun, B.; Hazar, L.; Yolaçan, R.; Keklikci, U. Evaluation of Retinal Microvascular Perfusion Changes in Patients with Celiac Disease. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30, 1876–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerman, E.; Esen, F.; Eraslan, M.; Kazokoglu, H. Orbital Myositis Associated with Celiac Disease. Int. Ophthalmol. 2014, 34, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, S.; Yeniad, B.; Peksayar, G. Regression of Conjunctival Tumor during Dietary Treatment of Celiac Disease. Indian. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 58, 433–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatansever, M.; Dursun, Ö.; Tezol, Ö.; Dinç, E.; Vatansever, E.; Sari, A.; Usta, Y. Effects of Laboratory Parameters on Tear Tests and Optical Coherence Tomography Findings in Pediatric Celiac Disease. Duzce Med. J. 2022, 24, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.G.d.S.; Miranda Sipahi, A.; dos Santos, F.M.; Schor, P.; Anschütz, A.; Mendes, L.G.A.; Silva, R. Eye Disorders in Patients with Celiac Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Study Using Clinical Data Warehouse. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 32, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Aggarwal, S.; Sharma, V. Bitot’s Spots: Look at the Gut. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 1058–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Witherspoon, S.R.; Callanan, D. Celiac Disease Presenting as a Xerophthalmic Fundus. Retina 2008, 28, 525–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.; Wright, T.; Weisbrod, D.; Ballios, B.G. Vitamin A Deficiency Retinopathy in the Setting of Celiac Disease and Liver Fibrosis. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2024, 149, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollazadegan, K.; Kugelberg, M.; Lindblad, B.E.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Increased Risk of Cataract among 28,000 Patients with Celiac Disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, U.K.; Goel, N.; Sud, R.; Thakar, M.; Ghosh, B. Bilateral Total Cataract as the Presenting Feature of Celiac Disease. Int. Ophthalmol. 2011, 31, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozates, S.; Doguizi, S.; Hosnut, F.O.; Sahin, G.; Sekeroglu, M.A.; Yilmazbas, P. Assessment of Corneal and Lens Density in Children with Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2019, 56, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, K.; Mishra, D.; Singh, T.R.R. Epidemiology of Ocular Manifestations in Autoimmune Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 744396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonicola, A.; Wieser, H.; Gizzi, C.; Soldaini, C.; Ciacci, C. Associations between Celiac Disease, Extra-Gastrointestinal Manifestations, and Gluten-Free Diet: A Narrative Overview. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshirfar, M.; Melanson, D.G.; Pandya, S.; Moin, K.A.; Talbot, C.L.; Hoopes, P.C. Implications of Celiac Disease in Prospective Corneal Refractive Surgery Patients: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, T.; Nie, L.; Wang, Y. Role of CD4+ T Cell-Derived Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Uveitis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 25, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnoli, L.I.M.; Varesi, A.; Barbieri, A.; Marchesi, N.; Pascale, A. Targeting the Gut-Eye Axis: An Emerging Strategy to Face Ocular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pytrus, W.; Akutko, K.; Pytrus, T.; Turno-Kręcicka, A. A Review of Ophthalmic Complications in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayar, K.; Tunç, R.; Pekel, H.; Esen, H.H.; Küçük, A.; Çifçi, S.; Ataseven, H.; Özdemir, M. Prevalence of Sicca Symptoms and Sjögren’s Syndrome in Coeliac Patients and Healthy Controls. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 49, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beas, R.; Altamirano-Farfan, E.; Izquierdo-Veraza, D.; Norwood, D.A.; Riva-Moscoso, A.; Godoy, A.; Montalvan-Sanchez, E.E.; Ramirez, M.; Guifarro, D.A.; Kitchin, E.; et al. Prevalence of Celiac Disease in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Sjögren Syndrome and Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Pardeshi, A.A.; Burkemper, B.; Apolo, G.; Cho, A.; Jiang, X.; Torres, M.; McKean-Cowdin, R.; Varma, R.; Xu, B.Y. Refractive Error and Anterior Chamber Depth as Risk Factors in Primary Angle Closure Disease: The Chinese American Eye Study. J. Glaucoma 2023, 32, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millington, R.S.; James-Galton, M.; Barbur, J.L.; Plant, G.T.; Bridge, H. Severe, Persistent Visual Impairment Associated with Occipital Calcification and Coeliac Disease. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 2056–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, H.A.; De Rosa, S.; Ruggieri, V.; de Dávila, M.T.G.; Fejerman, N. Epilepsy, Occipital Calcifications, and Oligosymptomatic Celiac Disease in Childhood. J. Child. Neurol. 2002, 17, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaender, M.; D’Souza, W.J.; Trost, N.; Litewka, L.; Paine, M.; Cook, M. Visual Disturbances Representing Occipital Lobe Epilepsy in Patients with Cerebral Calcifications and Coeliac Disease: A Case Series. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2004, 75, 1623–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Steinemann, T.L. Vitamin A Deficiency and the Eye. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2000, 40, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.; Dillon, A.; Watson, S. Vitamin A Deficiency and Xerophthalmia in Children of a Developed Country. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2016, 52, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.N.; Zhang, X.J.; Ling, X.T.; Bui, C.H.T.; Wang, Y.M.; Ip, P.; Chu, W.K.; Chen, L.J.; Tham, C.C.; Yam, J.C.; et al. Vitamin D and Ocular Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, E.; Hazar, L.; Çağlayan, M.; Şeker, Ö.; Çelebi, A.R.C. Peripapillary Choroidal Thickness in Patients with Vitamin D Deficiency. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbostan Soysal, G.; Berhuni, M.; Özer Özcan, Z.; Tıskaoğlu, N.S.; Kaçmaz, Z. Decreased Choroidal Vascularity Index and Subfoveal Choroidal Thickness in Vitamin D Insufficiency. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 44, 103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öncül, H.; Alakus, M.F.; Çağlayan, M.; Öncül, F.Y.; Dag, U.; Arac, E. Changes in Choroidal Thickness after Vitamin D Supplementation in Patients with Vitamin D Deficiency. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 55, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, E.; Ilhan, C.; Aksoy Aydemir, G.; Bayat, A.H.; Bolu, S.; Asik, A. Evaluation of Retinal Structure in Pediatric Subjects with Vitamin D Deficiency. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 233, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Icel, E.; Ucak, T.; Ugurlu, A.; Erdol, H. Changes in Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Patients with Vitamin D Deficiency. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 32, 3514–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkasap, S.; Türkyilmaz, K.; Dereci, S.; Öner, V.; Calapoǧlu, T.; Cüre, M.C.; Durmuş, M. Assessment of Peripapillary Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in Children with Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2013, 29, 2281–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Icel, E.; Ucak, T. The Effects of Vitamin B12 Deficiency on Retina and Optic Disk Vascular Density. Int. Ophthalmol. 2021, 41, 3145–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, S.; Bozkurt, E.; Dogan, M.; Yavasoglu, F.; Erogul, Ö.; Bulut, A.K. Effects of B12 Deficiency Anemia on Radial Peripapillary and Macular Vessel Density: An Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography (OCTA) Study. Klin. Monbl. Augenheilkd. 2023, 240, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fousekis, F.S.; Beka, E.T.; Mitselos, I.V.; Milionis, H.; Christodoulou, D.K. Thromboembolic Complications and Cardiovascular Events Associated with Celiac Disease. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 190, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, N.; Pantic, I.; Jevtic, D.; Mogulla, V.; Oluic, S.; Durdevic, M.; Nordin, T.; Jecmenica, M.; Milovanovic, T.; Gavrancic, T.; et al. Celiac Disease and Thrombotic Events: Systematic Review of Published Cases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccio, E.J.; Lewis, S.K.; Biviano, A.B.; Iyer, V.; Garan, H.; Green, P.H. Cardiovascular Involvement in Celiac Disease. World J. Cardiol. 2017, 9, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subtype of Celiac Disease | Definition | Typical Clinical Presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Classical | Intestinal mucosal damage with positive celiac-specific serology and symptoms resulting from malabsorption | Diarrhea, abdominal distension, poor growth in children, anemia, nutrient deficiencies, failure to thrive, delayed puberty; may include extraintestinal manifestations |

| Non-classical | Intestinal mucosal damage with positive serology but without overt malabsorption symptoms | Extraintestinal manifestations, such as iron deficiency anemia, osteoporosis, liver enzyme elevation, neurologic symptoms, infertility, dental enamel defects, and gastrointestinal symptoms, may be mild or absent |

| Subclinical | Positive serology and intestinal damage without clinical symptoms | Often discovered through screening (family members, associated autoimmune diseases, type 1 diabetes, Down syndrome); symptoms below the threshold of clinical detection, often having clinical (enamel defects…) and/or laboratory signs (iron deficiency anemia, liver function abnormalities) |

| Asymptomatic | Positive serology with intestinal injury in patients with no clinical or laboratory signs or symptoms | Often discovered through screening; no response to gluten withdrawal |

| Potential | Positive celiac-specific antibodies and genetic susceptibility, but a normal intestinal biopsy | May be symptomatic or asymptomatic; some progress to overt celiac disease, especially if persistently exposed to gluten |

| Authors and Year | Aim of Studies | Types of Studies Included | Number of Eyes/Patients Included | Summary of Results | Level of Evidence | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gumus et al., 2022 | Retinal and choroidal vasculature in newly diagnosed CD | Cross-sectional case–control OCTA study (DRI-OCT Triton, Topcon) | 44 right eyes of patients newly diagnosed with CD and 44 healthy patients | ↑ central section of the superficial and deep vascular plexuses; reduced temporal and nasal vessel density for choriocapillaris; thinner choroid in CD, more evident in females | Moderate | [18] |

| Bilgin & Sahin, 2023 | OCT findings in pediatric CD with adherence to GFD | Cross-sectional pediatric OCT study (Optovue RTVue OCT) | 68 eyes of 34 patients (14 patients who adhere to GFD, 20 who do not adhere to GFD) | Adhering to a GFD does not make any difference in choroidal, GCC, RNFL, and foveal thicknesses in pediatric CD patients | Moderate | [19] |

| Dereci et al., 2021 | OCT findings in pediatric CD | Cross-sectional case–control study SD-OCT (Spectralis, Heidelberg) | 43 CD patients and 48 healthy children | After 1 year of GFD in CD patients: thinning of the subfoveal, nasal, and temporal areas of the choroid | Moderate | [20] |

| Mollazadegan et al., 2012 | Risk of uveitis in CD | Nationwide cohort study | >28,000 CD patients vs. controls | CD associated with ↑ the risk of uveitis, even 5 years after CD diagnosis | High | [26] |

| Krifa et al., 2010 | Case: uveitis in a child with CD and diabetes mellitus type 1 | Case report | 1 patient | Uveitis resolved with GFD | Low | [27] |

| Klack et al., 2011 | Case: uveitis in an adult with CD | Case report | 1 patient | Uveitis remission after GFD | Low | [28] |

| Milstein et al., 2023 | Risk of CD in uveitis patients | Multicenter observational study | 112 patients with non-infectious uveitis | Increased risk of CD in uveitis patients | Moderate | [29] |

| Uzel et al., 2017 | Ocular surface parameters in adult CD | Cross-sectional case–control study | 56 eyes of 28 CD patients and 58 eyes of 29 healthy adults | Tear-film functions and conjunctival surface epithelial morphology altered in CD patients | Moderate | [30] |

| Karatepe Hashas et al., 2017 | Ocular involvement in children with CD | Cross-sectional case–control pediatric study SD-OCT (Spectralis, Heidelberg) | 31 CD children and 34 children in the control group | ↓ in RNFL thickness; anterior chamber shallowing; qualitative and quantitative reduction in tears | Moderate | [31] |

| Hazar et al., 2021 | Ocular parameters in adult CD patients | Cross-sectional case–control study (Optovue RTVue OCT) | 58 eyes of 31 CD patients and 50 eyes of 50 controls | In CD group: lower tear film parameters, changed segmental RNFL thickness, and larger anterior chamber depth | Moderate | [32] |

| Hodžić et al., 2024 | Dry eye in CD | Observational study (research for a randomized clinical trial) | 100 CD patients | Subjective and objective measures of dry eye were lower in CD patients who consumed food that may contain gluten | Moderate | [33] |

| De Bernardo et al., 2022 | Anterior segment and corneal parameters in CD | Observational case–control study (IOL Master, Pentacam HR) | 70 CD patients and 70 healthy controls | No major corneal and anterior segment changes between the two groups | Moderate | [34] |

| Gad et al., 2020 | Corneal nerves in pediatric CD | Cross-sectional case–control study (confocal microscopy) | 20 CD pediatric patients and 20 healthy controls | Minimal evidence of neuropathy in children with CD | Moderate | [35] |

| Isik et al., 2022 | Retinal vasculature of the retina and choroid in children with CD | Cross-sectional case–control OCTA study | 60 CD pediatric patients and 71 healthy controls | No statistically significant differences in vessel density, FAZ, and choroidal thickness | Moderate | [36] |

| Doğan et al., 2020 | Choroidal thickness and adherence to GFD | Cross-sectional case–control OCT study (SD-OCT, Retinascan RS-3000, Nidek) | 42 CD patients and 42 healthy controls | Longer duration of GFD was associated with adherence difficulty and thinner choroidal thickness | Moderate | [37] |

| Bolukbasi et al., 2019 | Choroidal thickness and pachychoroid in CD | Cross-sectional case–control SD-OCT study (Spectralis, Heidelberg) | 70 CD patients and 70 healthy controls | ↑ choroidal thickness in CD patients | Moderate | [38] |

| De Bernardo et al., 2021 | Choroidal structure in CD | Cross-sectional case–control EDI-OCT study (Spectralis, Heidelberg) | 74 CD patients and 67 healthy patients | ↑ choroidal thickness in CD patients (increased vascular and stromal components) | Moderate | [39] |

| Malhi et al., 2018 | CRVO in CD | Case reports | 2 patients | CRVO led to CD diagnosis | Low | [40] |

| Zoubeidi et al., 2016 | CRVO in CD | Case report | 1 patient | Non-ischemic CRVO as the first sign of CD | Low | [41] |

| Lee & Pulido, 2005 | CRVO in CD | Case report | 1 patient | Non-ischemic CRVO in the CD patient | Low | [42] |

| Erdem et al., 2022 | Retinal microvascular changes in CD | Cross-sectional case–control study (Optovue AngioVue OCT) | 30 CD patients and 30 controls | Reduced vessel density of the optic nerve head and radial peripapillary capillary; | Moderate | [43] |

| Cerman et al., 2014 | Orbital myositis in CD | Case report | 1 patient | Myositis improved with GFD and immunosuppression | Low | [44] |

| Tuncer et al., 2010 | Regression of conjunctival tumor with GFD in CD | Case report | 1 pediatric patient | Tumor regressed after GFD—presumed diagnosis of conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma | Low | [45] |

| Vatansever et al., 2022 | Lab parameters and ocular findings in pediatric CD | Cross-sectional case–control study (SD-OCT, Retinascan RS-3000, Nidek) | 100 eyes of 50 pediatric CD patients and 110 eyes of 55 healthy controls | ↓ Schirmer test and TBUT results in the CD group, positively correlated with Vit D; ↓ macular and RNFL thickness in the CD group | Moderate | [46] |

| Martins dos Santos et al., 2022 | Eye disorders in CD/IBD (data warehouse) | Cross-sectional retrospective data study | 272,873 patients with eye disease were evaluated between 2003 and 2019 | ↑ prevalence of anterior uveitis, cataract, dry eye, diabetic retinopathy, pathological myopia, and AMD in CD | Moderate | [47] |

| Sharma et al., 2014 | Bitot’s spots and CD | Case report | 1 child | Bitot’s spots → Vit A deficiency → CD | Low | [48] |

| Witherspoon & Callanan, 2008 | Xerophthalmic fundus in CD | Case report | 1 patient | Vit A deficiency fundus improved with Vit A + GFD | Low | [49] |

| Pereira et al., 2024 | Vit A deficiency retinopathy in CD + liver fibrosis | Case report | 1 patient | Severe retinopathy in a CD patient from Vit A deficiency | Low | [50] |

| Mollazadegan et al., 2011 | Risk of cataract in CD | Population cohort study | 28,756 CD patients | ↑ risk of cataract (HR ~1.3) | High | [51] |

| Raina et al., 2011 | Bilateral cataract as the first sign of CD | Case report | 1 patient | Bilateral, total, subluxated cataract in a young CD patient | Low | [52] |

| Ozates et al., 2019 | Corneal and lens density in pediatric CD | Cross-sectional case–control study (Pentacam HR) | 50 CD patients and 51 healthy controls | ↑ maximum lens density in patients with CD; ↑ peripheral corneal density in female patients with CD | Moderate | [53] |

| Nutrient Deficiency | Ocular Manifestations | Proposed Mechanism | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | Xerophthalmia Bitot’s spots Nyctalopia Conjunctival keratinization Keratomalacia | Loss of goblet cells, Squamous metaplasia Rod dysfunction | Systematic review [21] Narrative review [66] Observational study [67] Case reports, anecdotal observations [48,49,50] |

| Vitamin D | Dry eye disease Cataract Myopia Age-related macular degeneration Glaucoma Diabetic retinopathy, Thyroid eye disease Uveitis Increased choroidal thickness RNFL thinning | Immunomodulation (Th1/Th17 regulation), Calcium homeostasis, Endothelial function | Systematic reviews [22,23,68]; Cross-sectional and small case–control OCT studies [69,70,71,72,73] |

| Iron | RNFL thinning Smaller foveal avascular zone (OCTA) Reduced capillary plexus density (OCTA) | Disrupted neuronal metabolism Ischemia | Systematic review and meta-analysis [25], Case–control and OCT study [46] |

| Folate and vitamin B12 | Cataract Optic neuropathy RNFL thinning Reduced retinal vascular density (OCTA) Increased risk of central retinal vein occlusion | Neurodegeneration Retinal microcirculation impairment | Case–control and OCT studies [24,46,74,75,76]; Epidemiology (cataract risk) [51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Senterkiewicz, M.; Szaflarska-Popławska, A.; Kałużny, B.J. Ocular Manifestations of Celiac Disease: Current Evidence and Clinical Implications. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3781. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233781

Senterkiewicz M, Szaflarska-Popławska A, Kałużny BJ. Ocular Manifestations of Celiac Disease: Current Evidence and Clinical Implications. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3781. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233781

Chicago/Turabian StyleSenterkiewicz, Monika, Anna Szaflarska-Popławska, and Bartłomiej J. Kałużny. 2025. "Ocular Manifestations of Celiac Disease: Current Evidence and Clinical Implications" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3781. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233781

APA StyleSenterkiewicz, M., Szaflarska-Popławska, A., & Kałużny, B. J. (2025). Ocular Manifestations of Celiac Disease: Current Evidence and Clinical Implications. Nutrients, 17(23), 3781. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233781