Is Vitamin D Fortification of Dairy Products Effective for Improving Vitamin D Status? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Certainty of Evidence

3. Results

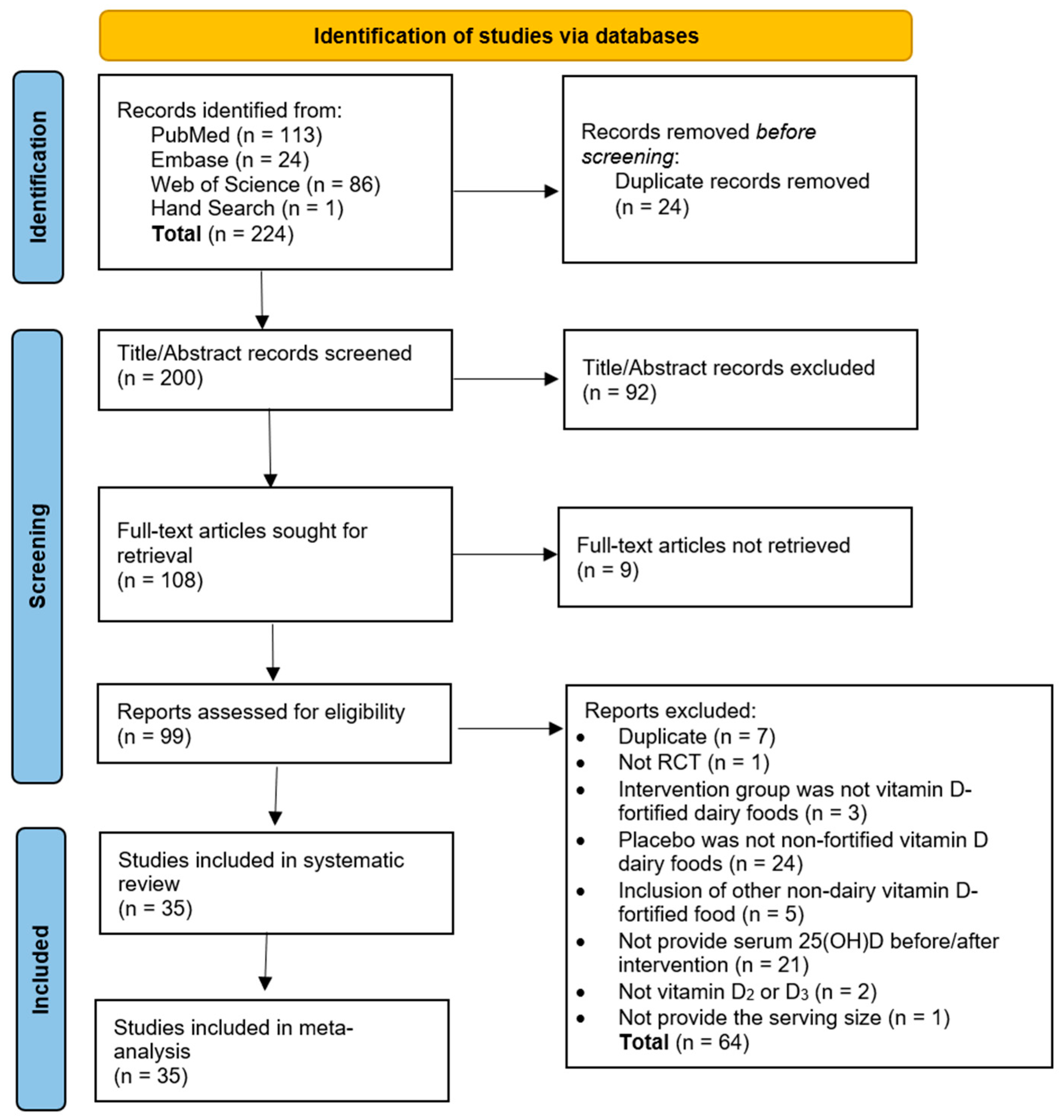

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.4. Efficacy of Vitamin D-Fortified Dairy Products in Improving Serum 25(OH)D Concentration

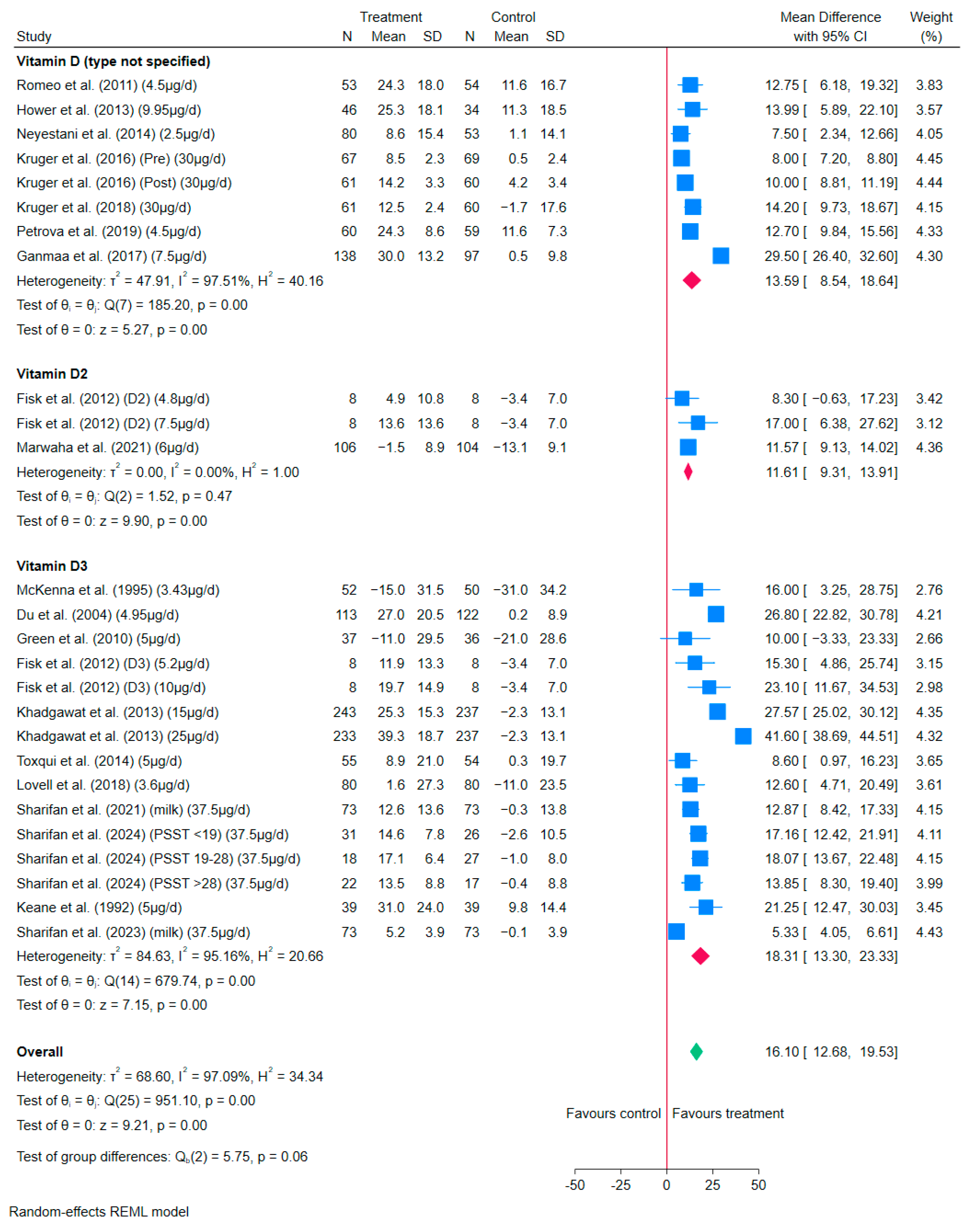

3.4.1. Vitamin D-Fortified Milk/Milk Powder

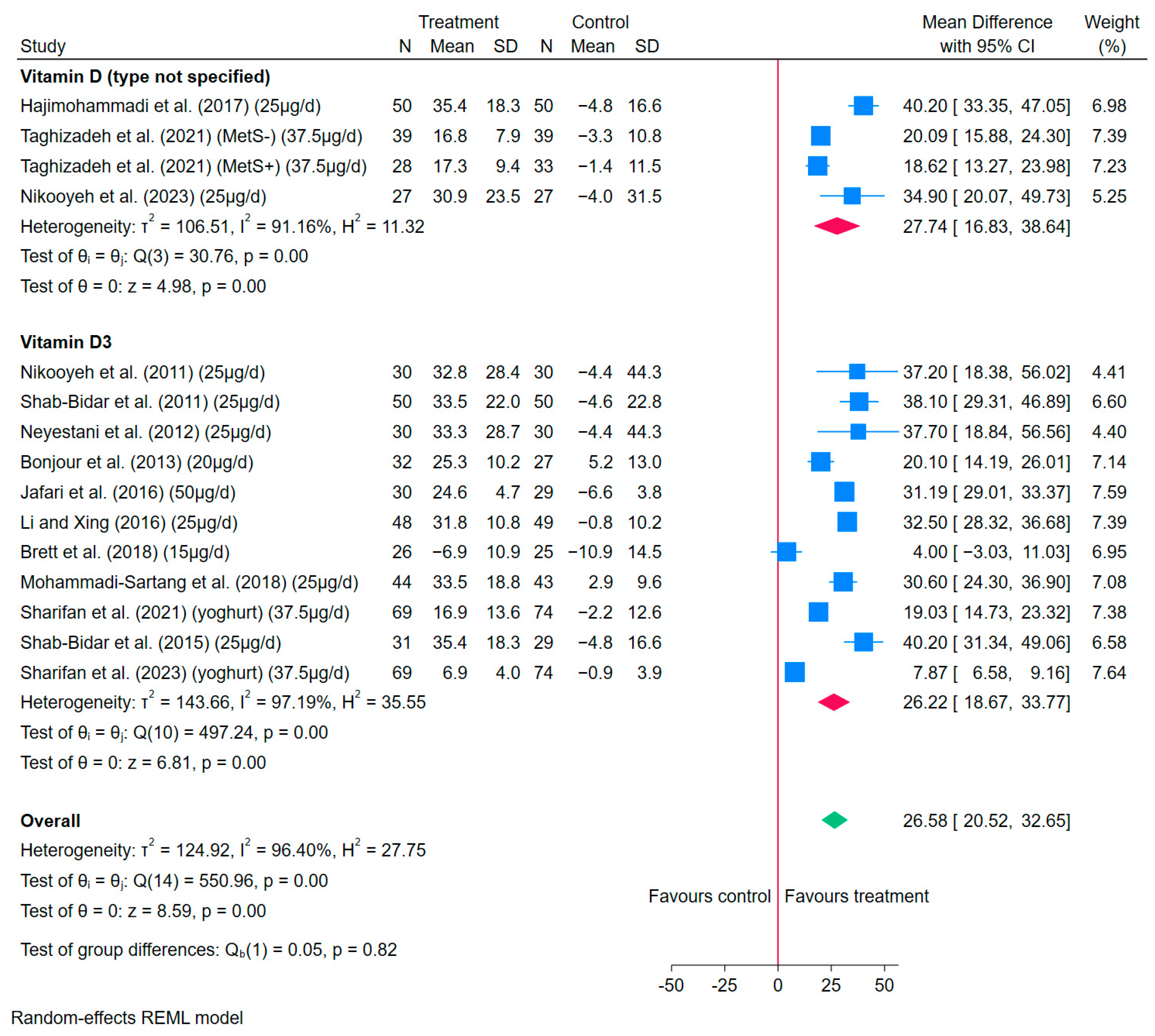

3.4.2. Vitamin D-Fortified Yoghurt and Yoghurt Drinks

3.4.3. Vitamin D-Fortified Cheese

3.5. Meta-Regression

3.6. Publication Bias

3.7. Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SACN. Vitamin D and Health. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a804e36ed915d74e622dafa/SACN_Vitamin_D_and_Health_report.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Santos, H.O.; Martins, C.E.C.; Forbes, S.C.; Delpino, F.M. A Scoping Review of Vitamin D for Nonskeletal Health: A Framework for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice. Clin. Ther. 2023, 45, e127–e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probosari, E.; Subagio, H.W.; Heri-Nugroho; Rachmawati, B.; Muis, S.F.; Tjandra, K.C.; Adiningsih, D.; Winarni, T.I. The Impact of Vitamin D Supplementation on Fasting Plasma Glucose, Insulin Sensitivity, and Inflammation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SACN. Fortifying Foods and Drinks with Vitamin D: Main Report. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/fortifying-food-and-drink-with-vitamin-d-a-sacn-rapid-review/fortifying-foods-and-drinks-with-vitamin-d-main-report#background (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- NDNS. National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme, Years 9 to 11 (2016/2017 to 2018/2019). A Survey Carried out on Behalf of Public Health England and the Food Standards Agency. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ndns-results-from-years-9-to-11-2016-to-2017-and-2018-to-2019 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- NDNS. National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) Results on the Diet, Nutrient Intake and Nutritional Status of Adults and Children in the UK for 2019 to 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-diet-and-nutrition-survey-2019-to-2023?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=govuk-notifications-topic&utm_source=491c9b58-0a08-409e-a954-8ab21506bc5c&utm_content=immediately (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Stewart, C.; McNeill, G.; Runions, R.; Comrie, F.; McDonald, A.; Jaacks, L.M. Meat and dairy consumption in Scottish adults: Insights from a national survey. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 37, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lovegrove, J.A.; Givens, D.I. Food fortification and biofortification as potential strategies for prevention of vitamin D deficiency. Nutr. Bull. 2019, 44, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEFRA. Accredited Official Statistics Family Food FYE 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/family-food-fye-2023/family-food-fye-2023#introduction (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Clark, B.; Doyle, J.; Bull, O.; McClean, S.; Hill, T. Knowledge and attitudes towards vitamin D food fortification. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 49, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DHSC. Guidance Fortified Foods: Guidance to Compliance on European Regulation (EC) No. 1925/2006 on the Addition of Vitamins and Minerals and Certain Other Substances to Food. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/fortified-foods-guidance-to-compliance-with-european-regulation-ec-no-1925-2006-on-the-addition-of-vitamins-and-minerals-and-certain-other-substances-to-food/fortified-foods-guidance-to-compliance-on-european-regulation-ec-no-19252006-on-the-addition-of-vitamins-and-minerals-and-certain-other-substance?utm_source=chatgpt.com#section-4 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Cashman, K.D.; O’Neill, C.M. Strategic food vehicles for vitamin D fortification and effects on vitamin D status: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 238, 106448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.J.; Seamans, K.M.; Cashman, K.D.; Kiely, M. An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Vitamin D Food Fortification. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlop, E.; Kiely, M.E.; James, A.P.; Singh, T.; Pham, N.M.; Black, L.J. Vitamin D Food Fortification and Biofortification Increases Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations in Adults and Children: An Updated and Extended Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2622–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brett, N.R.; Gharibeh, N.; Weiler, H.A. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation, Food Fortification, or Bolus Injection on Vitamin D Status in Children Aged 2–18 Years: A Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikooyeh, B.; Neyestani, T.R. The effects of vitamin D-fortified foods on circulating 25(OH)D concentrations in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 1821–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparri, C.; Perna, S.; Spadaccini, D.; Alalwan, T.; Girometta, C.; Infantino, V.; Rondanelli, M. Is vitamin D-fortified yogurt a value-added strategy for improving human health? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 8587–8603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5 (Updated August 2024). Available online: https://www.cochrane.org/authors/handbooks-and-manuals/handbook/current/chapter-06 (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health. Vitamin D Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/#:~:text=*Serum%20concentrations%20of%2025(OH,mL%20%3D%202.5%20nmol%2FL (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- NHS. Vitamin D. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vitamins-and-minerals/vitamin-d/#:~:text=A%20microgram%20(mcg)%20is%201%2C000,is%20equal%20to%2040%20IU (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Green, T.J.; Skeaff, C.M.; Rockell, J.E. Milk fortified with the current adequate intake for vitamin D (5 microg) increases serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D compared to control milk but is not sufficient to prevent a seasonal decline in young women. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 19, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kedlaya, K. Proof of a Mixed Arithmetic-Mean, Geomertic-Mean Inequality. Am. Math. Mon. 1994, 101, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. Available online: https://www.stata.com/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS. Overview Obesity. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/obesity/#:~:text=index%20(BMI).-,Body%20mass%20index%20(BMI),in%20the%20severely%20obese%20range (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Brett, N.R.; Parks, C.A.; Lavery, P.; Agellon, S.; Vanstone, C.A.; Kaufmann, M.; Jones, G.; Maguire, J.L.; Rauch, F.; Weiler, H.A. Vitamin D status and functional health outcomes in children aged 2-8 y: A 6-mo vitamin D randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. A Nonparametric “Trim and Fill” Method of Accounting for Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2000, 95, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M. Introduction to the GRADE tool for rating certainty in evidence and recommendations. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 25, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhu, K.; Trube, A.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, G.; Hu, X.; Fraser, D.R.; Greenfield, H. School-milk intervention trial enhances growth and bone mineral accretion in Chinese girls aged 10–12 years in Beijing. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikooyeh, B.; Neyestani, T.R.; Farvid, M.; Alavi-Majd, H.; Houshiarrad, A.; Kalayi, A.; Shariatzadeh, N.; Gharavi, A.; Heravifard, S.; Tayebinejad, N.; et al. Daily consumption of vitamin D- or vitamin D + calcium-fortified yogurt drink improved glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shab-Bidar, S.; Neyestani, T.R.; Djazayery, A.; Eshraghian, M.R.; Houshiarrad, A.; Gharavi, A.; Kalayi, A.; Shariatzadeh, N.; Zahedirad, M.; Khalaji, N.; et al. Regular consumption of vitamin D-fortified yogurt drink (Doogh) improved endothelial biomarkers in subjects with type 2 diabetes: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyestani, T.R.; Nikooyeh, B.; Alavi-Majd, H.; Shariatzadeh, N.; Kalayi, A.; Tayebinejad, N.; Heravifard, S.; Salekzamani, S.; Zahedirad, M. Improvement of vitamin D status via daily intake of fortified yogurt drink either with or without extra calcium ameliorates systemic inflammatory biomarkers, including adipokines, in the subjects with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadgawat, R.; Marwaha, R.K.; Garg, M.K.; Ramot, R.; Oberoi, A.K.; Sreenivas, V.; Gahlot, M.; Mehan, N.; Mathur, P.; Gupta, N. Impact of vitamin D fortified milk supplementation on vitamin D status of healthy school children aged 10-14 years. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 2335–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyestani, T.R.; Hajifaraji, M.; Omidvar, N.; Nikooyeh, B.; Eshraghian, M.R.; Shariatzadeh, N.; Kalayi, A.; Khalaji, N.; Zahedirad, M.; Abtahi, M.; et al. Calcium-vitamin D-fortified milk is as effective on circulating bone biomarkers as fortified juice and supplement but has less acceptance: A randomised controlled school-based trial. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shab-Bidar, S.; Neyestani, T.; Djazayery, A. Response of central obesity to vitamin D intake in the subjects with type-2 diabetes. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 1, 416. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, T.; Faghihimani, E.; Feizi, A.; Iraj, B.; Javanmard, S.H.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Fallah, A.A.; Askari, G. Effects of vitamin D-fortified low fat yogurt on glycemic status, anthropometric indexes, inflammation, and bone turnover in diabetic postmenopausal women: A randomised controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.C.; Chan, Y.M.; Kuhn-Sherlock, B.; Lau, L.T.; Lau, C.; Chin, Y.S.; Todd, J.M.; Schollum, L.M. Differential effects of calcium- and vitamin D-fortified milk with FOS-inulin compared to regular milk, on bone biomarkers in Chinese pre- and postmenopausal women. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 1911–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Xing, B. Vitamin D3-Supplemented Yogurt Drink Improves Insulin Resistance and Lipid Profiles in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Double Blinded Clinical Trial. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 68, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganmaa, D.; Stuart, J.J.; Sumberzul, N.; Ninjin, B.; Giovannucci, E.; Kleinman, K.; Holick, M.F.; Willett, W.C.; Frazier, L.A.; Rich-Edwards, J.W. Vitamin D supplementation and growth in urban Mongol school children: Results from two randomized clinical trials. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajimohammadi, M.; Shab-Bidar, S.; Neyestani, T.R. Consumption of vitamin D-fortified yogurt drink increased leptin and ghrelin levels but reduced leptin to ghrelin ratio in type 2 diabetes patients: A single blind randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.C.; Chan, Y.M.; Lau, L.T.; Lau, C.C.; Chin, Y.S.; Kuhn-Sherlock, B.; Todd, J.M.; Schollum, L.M. Calcium and vitamin D fortified milk reduces bone turnover and improves bone density in postmenopausal women over 1 year. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2785–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi-Sartang, M.; Bellissimo, N.; de Zepetnek, J.O.T.; Brett, N.R.; Mazloomi, S.M.; Fararouie, M.; Bedeltavana, A.; Famouri, M.; Mazloom, Z. The effect of daily fortified yogurt consumption on weight loss in adults with metabolic syndrome: A 10-week randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marwaha, R.K.; Dabas, A.; Puri, S.; Kalaivani, M.; Dabas, V.; Yadav, S.; Dang, A.; Pullakhandam, R.; Gupta, S.; Narang, A. Efficacy of Daily Supplementation of Milk Fortified with Vitamin D2 for Three Months in Healthy School Children: A Randomized Placebo Controlled Trial. Indian. Pediatr. 2021, 58, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifan, P.; Ziaee, A.; Darroudi, S.; Rezaie, M.; Safarian, M.; Eslami, S.; Khadem-Rezaiyan, M.; Tayefi, M.; Mohammadi Bajgiran, M.; Ghazizadeh, H.; et al. Effect of low-fat dairy products fortified with 1500IU nano encapsulated vitamin D(3) on cardiometabolic indicators in adults with abdominal obesity: A total blinded randomized controlled trial. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2021, 37, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, N.; Sharifan, P.; Toosi, M.S.E.; Doust, F.N.S.; Darroudi, S.; Afshari, A.; Rezaie, M.; Safarian, M.; Vatanparast, H.; Eslami, S.; et al. The effects of consuming a low-fat yogurt fortified with nano encapsulated vitamin D on serum pro-oxidant-antioxidant balance (PAB) in adults with metabolic syndrome; a randomized control trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 102332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikooyeh, B.; Zahedirad, M.; Kalayi, A.; Shariatzadeh, N.; Hollis, B.W.; Neyestani, T.R. Improvement of vitamin D status through consumption of either fortified food products or supplement pills increased hemoglobin concentration in adult subjects: Analysis of pooled data from two randomized clinical trials. Nutr. Health 2023, 29, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifan, P.; Darroudi, S.; Rafiee, M.; Geraylow, K.R.; Hemmati, R.; Rashidmayvan, M.; Safarian, M.; Eslami, S.; Vatanparast, H.; Zare-Feizabadi, R.; et al. The effects of low-fat dairy products fortified with 1500 IU vitamin D3 on serum liver function biomarkers in adults with abdominal obesity: A randomized controlled trial. J. Heatlh Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifan, P.; Sahranavard, T.; Rashidmayvan, M.; Darroudi, S.; Fard, M.V.; Mohammadhasani, K.; Mansoori, A.; Eslami, S.; Safarian, M.; Afshari, A.; et al. Effect of dairy products fortified with vitamin d(3) on restless legs syndrome in women with premenstrual syndrome, abdominal obesity and vitamin d deficiency: A pilot study. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, E.M.; Rochfort, A.; Cox, J.; McGovern, D.; Coakley, D.; Walsh, J.B. Vitamin-D-fortified liquid milk—A highly effective method of vitamin D administration for house-bound and institutionalised elderly. Gerontology 1992, 38, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M.J.; Freaney, R.; Byrne, P.; McBrinn, Y.; Murray, B.; Kelly, M.; Donne, B.; O’Brien, M. Safety and efficacy of increasing wintertime vitamin D and calcium intake by milk fortification. QJM 1995, 88, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Romeo, J.; Wärnberg, J.; García-Mármol, E.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, M.; Diaz, L.E.; Gomez-Martínez, S.; Cueto, B.; López-Huertas, E.; Cepero, M.; Boza, J.J.; et al. Daily consumption of milk enriched with fish oil, oleic acid, minerals and vitamins reduces cell adhesion molecules in healthy children. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisk, C.M.; Theobald, H.E.; Sanders, T.A. Fortified malted milk drinks containing low-dose ergocalciferol and cholecalciferol do not differ in their capacity to raise serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in healthy men and women not exposed to UV-B. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1286–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonjour, J.P.; Benoit, V.; Payen, F.; Kraenzlin, M. Consumption of yogurts fortified in vitamin D and calcium reduces serum parathyroid hormone and markers of bone resorption: A double-blind randomized controlled trial in institutionalized elderly women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 2915–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hower, J.; Knoll, A.; Ritzenthaler, K.L.; Steiner, C.; Berwind, R. Vitamin D fortification of growing up milk prevents decrease of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations during winter: A clinical intervention study in Germany. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 172, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxqui, L.; Pérez-Granados, A.M.; Blanco-Rojo, R.; Wright, I.; de la Piedra, C.; Vaquero, M.P. Low iron status as a factor of increased bone resorption and effects of an iron and vitamin D-fortified skimmed milk on bone remodelling in young Spanish women. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manios, Y.; Moschonis, G.; Mavrogianni, C.; van den Heuvel, E.; Singh-Povel, C.M.; Kiely, M.; Cashman, K.D. Reduced-fat Gouda-type cheese enriched with vitamin D(3) effectively prevents vitamin D deficiency during winter months in postmenopausal women in Greece. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2367–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, D.; Bernabeu Litran, M.A.; Garcia-Marmol, E.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, M.; Cueto-Martin, B.; Lopez-Huertas, E.; Catena, A.; Fonolla, J. IEffects of fortified milk on cognitive abilities in school-aged children: Results from a randomized-controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L.; Mistry, V.V.; Vukovich, M.D.; Hogie-Lorenzen, T.; Hollis, B.W.; Specker, B.L. Bioavailability of vitamin D from fortified process cheese and effects on vitamin D status in the elderly. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 2295–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.; Sidhom, G.; Whiting, S.J.; Rousseau, D.; Vieth, R. The Bioavailability of Vitamin D from Fortified Cheeses and Supplements Is Equivalent in Adults12. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Lucas, T.S.; Duncan, A.M.; Rabasa-Lhoret, R.; Vieth, R.; Gibbs, A.; Badawi, A.; Wolever, T.M.S. Effect of Vitamin D Fortified Cheese on Oral Glucose Tolerance in Individuals Exhibiting Marginal Vitamin D Status and an Increased Risk for Developing Type 2 Diabetes: A Double-Blind, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 917.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, A.L.; Davies, P.S.W.; Hill, R.J.; Milne, T.; Matsuyama, M.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, R.X.; Wouldes, T.A.; Heath, A.M.; Grant, C.C.; et al. Compared with Cow Milk, a Growing-Up Milk Increases Vitamin D and Iron Status in Healthy Children at 2 Years of Age: The Growing-Up Milk-Lite (GUMLi) Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1570–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandar, R.; Pullakhandam, R.; Kulkarni, B.; Sachdev, H.S. Relative Efficacy of Vitamin D2 and Vitamin D3 in Improving Vitamin D Status: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Jackson, K.G.; Che Taha, C.S.B.; Li, Y.; Givens, D.I.; Lovegrove, J.A. A 25-Hydroxycholecalciferol-Fortified Dairy Drink Is More Effective at Raising a Marker of Postprandial Vitamin D Status than Cholecalciferol in Men with Suboptimal Vitamin D Status. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 2076–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.D.; Seamans, K.M.; Lucey, A.J.; Stöcklin, E.; Weber, P.; Kiely, M.; Hill, T.R. Relative effectiveness of oral 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and vitamin D3 in raising wintertime serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in older adults1234. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efsa Panel on Nutrition, N.F.; Food, A.; Turck, D.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Kearney, J.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; et al. Safety of calcidiol monohydrate produced by chemical synthesis as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, E.B.; Barbano, D.M.; Drake, M. Vitamin Fortification of Fluid Milk. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfakianakis, P.; Tzia, C. Conventional and Innovative Processing of Milk for Yogurt Manufacture; Development of Texture and Flavor: A Review. Foods 2014, 3, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, A.G.; Pimentel, T.C.; Esmerino, E.A.; Verruck, S. Dairy Foods Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mazahery, H.; von Hurst, P.R. Factors Affecting 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration in Response to Vitamin D Supplementation. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5111–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorde, R.; Sneve, M.; Emaus, N.; Figenschau, Y.; Grimnes, G. Cross-sectional and longitudinal relation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and body mass index: The Tromsø study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2010, 49, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, W.; Barnett-Griness, O.; Rennert, G. The relationship between obesity and the increase in serum 25(OH)D levels in response to vitamin D supplementation. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashi, P.G.; Lammersfeld, C.A.; Braun, D.P.; Gupta, D. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is inversely associated with body mass index in cancer. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscemi, S.; Buscemi, C.; Corleo, D.; De Pergola, G.; Caldarella, R.; Meli, F.; Randazzo, C.; Milazzo, S.; Barile, A.M.; Rosafio, G.; et al. Obesity and Circulating Levels of Vitamin D Before and After Weight Loss Induced by a Very Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Food Additives Permitted for Direct Addition to Food for Human Consumption; Vitamin D2 and Vitamin D3. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/07/18/2016-16738/food-additives-permitted-for-direct-addition-to-food-for-human-consumption-vitamin-d2-and-vitamin-d3 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Batman, A.; Saygili, E.S.; Yildiz, D.; Sen, E.C.; Erol, R.S.; Canat, M.M.; Ozturk, F.Y.; Altuntas, Y. Risk of hypercalcemia in patients with very high serum 25-OH vitamin D levels. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoušek, J.; Pilařová, V.; Macáková, K.; Nomura, A.; Veiga-Matos, J.; Silva, D.D.d.; Remião, F.; Saso, L.; Malá-Ládová, K.; Malý, J.; et al. Vitamin D: Sources, physiological role, biokinetics, deficiency, therapeutic use, toxicity, and overview of analytical methods for detection of vitamin D and its metabolites. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2022, 59, 517–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galior, K.; Grebe, S.; Singh, R. Development of Vitamin D Toxicity from Overcorrection of Vitamin D Deficiency: A Review of Case Reports. Nutrients 2018, 10, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and FoodAllergens; Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.-I.; Knutsen, H.K.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the Tolerable Upper Intake Level of vitamin D. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Abrams, S.A.; Aloia, J.F.; Brannon, P.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What Clinicians Need to Know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.E.; Dangour, A.D.; Tedstone, A.E.; Chalabi, Z. Does fortification of staple foods improve vitamin D intakes and status of groups at risk of deficiency? A United Kingdom modeling study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, R.R.; Johnston, M.; Lowis, C.; Fearon, A.M.; Stewart, S.; Strain, J.J.; Pourshahidi, L.K. Vitamin D3 content of cows’ milk produced in Northern Ireland and its efficacy as a vehicle for vitamin D fortification: A UK model. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 72, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itkonen, S.T.; Erkkola, M.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.J.E. Vitamin D Fortification of Fluid Milk Products and Their Contribution to Vitamin D Intake and Vitamin D Status in Observational Studies—A Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashman, K.D. Vitamin D fortification of foods—Sensory, acceptability, cost, and public acceptance considerations. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 239, 106494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BNF. Your Balanced Diet Get Portion Wise! Available online: https://www.nutrition.org.uk/media/pwdjfvj5/your-balanced-diet_16pp_final_web.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Characteristics of Participants | Intervention Group | Placebo Group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Int (n); Ctrl (n) | Trial Duration; Season | Health Status | Age (Years) | BMI at Baseline (kg/m2) | Ethnicity | Dairy Type; Vit D (µg/d) | Serum 25(OH)D at Baseline (nmol/L) | Serum 25(OH)D at Endpoint (nmol/L) | Placebo | Serum 25(OH)D at Baseline (nmol/L) | Serum 25(OH)D at Endpoint (nmol/L) | |

| McKenna et al. (1995) [53] | Ireland | 52; 50 | 6 months; Winter | Healthy | Median: 22.6, range: 17–54 | NA | NA | Vit D3-fortified milk (Ca: 1525 mg/L); 3.4 | 77 ± 35 | 62 ± 26 | Unfortified milk; | 85 ± 39 | 54 ± 25 |

| Du et al. (2004) [32] | China | 113; 122 | 2 years; NA | Healthy | 10 | Int: 16.8 ± 2.6 Ctrl: 16.8 ± 2.6 | Chinese | Vit D3-fortified milk (with Ca); 5.0 | 20.6 ± 8.8 | 47.6 ± 23.4 | Unfortified milk; | 17.7 ± 8.7 | 17.9 ± 9.0 |

| Green et al. (2010) [22] | New Zealand | 37; 36 | 12 weeks; Summer to Autumn | Healthy | Int: 28.0 (95% CI: 25.5–30.6) Ctrl: 28.8 (95% CI: 26.3–31.3) | Int: 23.3 (95% CI: 22.9–25.8) Ctrl: 23.7 (95% CI: 22.4–25.0) | European: Int (78.4%) Ctrl (91.7%); Asian: Int (16.2%) Ctrl (5.6%); Indian: Int (5.4%) Ctrl (2.8%) | Vit D3-fortified milk powder, dissolved in 200 mL of water; 5 | ≤76 ± 32.6 1 | ≤65 ± 24.8 1 | Unfortified milk; | ≤74 ± 30.6 1 | ≤53 ± 26.0 1 |

| Romeo et al. (2011) [54] | Spain | 53; 54 | 5 months; NA | Healthy | Boys: 11.4 ± 2.17; Girls: 11.5 ± 2.30 | Int: 19.3 ± 3.88; Ctrl: 20.29 ± 3.30 | NA | Vit D-fortified milk *; 4.5 | 68.98 ± 15.13 | 93.33 ± 19.85 | Standard whole milk | 68.7 ± 13.58 | 80.3 ± 18.65 |

| Fisk et al. (2012) [55] | United Kingdom | D2 (5 µg): 8 D3 (5 µg): 8 D2 (10 µg): 8 D3 (10 µg): 8; Ctrl: 8 | 4 weeks; Winter | Healthy | Median (range): Int: 3.8 (2.0–6.8) Ctrl: 3.7 (2.0–6.2) | Median (range): Int: 15.6 (13.0–22.1) Ctrl: 15.4 (14.1–20.0) | Light skinned: Int (n = 46) Ctrl (n = 32); Dark skinned: Int (n = 0) Ctrl (n = 2) | Vit D2/D3-fortified malted milk drink; Vit D2: 4.8 and 7.5 Vit D3: 5.2 and 10 | D2 (5 µg): 48.0 ± 26.6 3 D3 (5 µg): 31.3 ± 22.1 3 D2 (10 µg): 41.9 ± 14.1 3 D3 (10 µg): 30.9 ± 29.1 3 | D2 (5 µg): 52.9 ± 20.53 4 D3 (5 µg): 43.2 ± 15.924 * D2 (10 µg): 55.5 ± 10.75 4 D3 (10 µg): 50.6 ± 21.48 4 | Unfortified malted milk drink; | 33.5 ± 13.3 3 | 30.1 ± 9.78 4 |

| Hower et al. (2013) [57] | Germany | 46; 34 | 9 months; Winter to summer | Healthy | Median (range): Int: 3.8 (2.0–6.8) Ctrl: 3.7 (2.0–6.2) | Median (range): Int: 15.6 (13.0–22.1) Ctrl: 15.4 (14.1–20.0) | Light skinned: Int: n = 46 Ctrl: n = 32 Dark skinned: Int: n = 0 Ctrl: n = 2 | Vit D-fortified growing-up milk; 9.975 | 60.23 ± 20.55 2 | 71.63 ± 13.58 2 | Unfortified semi-skimmed cow’s milk | 58.30 ± 21.2 2 | 69.61 ± 13.08 2 |

| Khadgawat et al. (2013) [36] | India | 15 µg: 243 25 µg: 233; 237 | 12 weeks; NA | Healthy | 15 µg: 11.75 ± 1.08 25 µg: 11.75 ± 1.14 Ctrl: 11.74 ± 1.05 | 15 µg: 18.84 ± 3.66 25 µg: 18.62 ± 3.50 Ctrl: 18.94 ± 3.33 | Indian | Vit D-fortified milk; 15 and 25 | 15 µg: 28.55 ± 13.1 25 µg: 29.85 ± 14.05 | 15 µg: 57.18 ± 16.88 25 µg: 69.18 ± 21.18 | Unfortified milk; NA | 29.35 ± 13.08 | 27.08 ± 13.1 |

| Neyestani et al. (2014) [37] | Iran | 80; 53 | 12 weeks; Winter | Healthy | 10–12 | Mean (SEM): Int: 18.3 (0.4) Ctrl: 18.3 (0.4) | Iranian | Vit D-fortified milk (with 500 mg of Ca); 2.5 | 25(OH)D3: 24.9 ± 12.5 5 | 25(OH)D3: 33.5 ± 16.1 5 | Plain milk (with 240 mg/200 mL of calcium); non-detectable | 25(OH)D3: 27.4 ± 13.8 5 | 25(OH)D3: 28.5 ± 13.1 5 |

| Toxqui et al. (2014) [58] | Spain | 55; 54 | 16 weeks; Winter | Healthy | Fe + vit D: 24.7 ± 4.6 Ctrl: 24.8 ± 4.1 | Fe + vit D: 21.4 ± 3.0 Ctrl: 21.9 ± 3.0 | Caucasian | Vit D3-fortified skimmed flavoured milk fortified (with 15 mg of Fe); 5 | 62.3 ± 20.8 | 71.2 ± 21.1 | Skimmed flavoured milk with fortified iron (15 mg/500 mL) | 62.9 ± 20.8 | 63.2 ± 18.3 |

| Kruger et al. (2016) [40] | Malaysia | Pre: 67 Post: 61; Pre: 69 Post: 60 | 12 weeks; NA | Postmenopausal and premenopausal | Pre: Int 42 ± 5.1 Ctrl 41 ± 5.1 Post: Int 60 ± 3.9 Ctrl 59 ± 4.3 | Pre: Int 23.0 ± 3.28 Ctrl 22.3 ± 3.21 Post: Int 23.4 ± 2.85 Ctrl 24.4 ± 2.88 | Malaysian Chinese | Pre: Vit D-fortified milk (1000 mg of Ca) Post: Vit D-fortified milk (1200 mg of Ca); 30 | Pre: 54.6 ± 2.49 Post: 57.3 ± 3.54 | Pre: 63.1 ± 2.03 Post: 71.5 ± 2.98 | Regular milk with 500 mg of calcium | Pre: 52.0 ± 2.72 Post: 59.3 ± 3.66 | Pre: 52.5 ± 2.00 Post: 63.5 ± 3.03 |

| Kruger et al. (2018) [44] | Malaysia | 61; 60 | 12 months; NA | Healthy | Int: 59 ± 3.9 Ctrl: 60 ± 4.3 | Int: 23.4 ± 2.94 Ctrl: 24.5 ± 2.94 | Malaysian Chinese | Vit D-fortified milk powder (1200 mg of calcium, 96 mg of magnesium, 2.4 mg of zinc, and 4 g of FOS-inulin); 30 | 25(OH)D3: 62.3 ± 1.89 | 25(OH)D3: 74.8 ± 2.74 | Regular milk | 25(OH)D3: 64.8 ± 18.89 | 25(OH)D3: 63.1 ± 2.87 |

| Lovell et al. (2018) [64] | New Zealand, Australia | 80; 80 | 12 months; All season | Healthy | 1 year ± 2 week | NA | NA | Vit D3-fortified growing-up milk-lite (fortified with 1.7 mg/100 mL of iron, probiotics and prebiotics); 3.6 | 90.4 ± 28.8 | 92.0 ± 25.5 | Unfortified cow milk | 85.9 ± 23.4 | 74.9 ± 23.5 |

| Petrova et al. (2019) [60] | Spain | 60; 59 | 5 months; winter | Healthy | 11 ± 2.14 | BMI (square root transformation) in mean (SE): Int: 4.34 (0.06) Ctrl: 4.51 (0.06) | NA | Vit D-fortified milk beverage (with vit A, B complex, C, and E, Ca, P, Zn, and fish oils) 4.5 | 66.0 ± 9.37 5 | 90.3 ± 7.44 5 | Regular full milk | 67.9 ± 7.30 5 | 79.5 ± 7.30 5 |

| Marwaha et al. (2021) [46] | India | 106; 104 | 3 months; winter | Healthy | Int: 10.3 ± 0.5 Ctrl: 10.4 ± 0.8 | Int: 16.7 ± 3.3 Ctrl: 16.8 ± 3.2 | Indian | Vit D2-fortified milk; 6 | 28.55 ± 9.075 | 27.025 ± 8.75 | Unfortified milk | 29.925 ± 9.475 | 16.825 ± 8.75 |

| Sharifan et al. (2021) [47] | Iran | Milk: 73 Yoghurt: 69; Milk: 73 Yoghurt: 74 | 10 weeks; winter | Abdominal obesity | Int: Milk 40.42 ± 8.03 Yoghurt: 43.47 ± 7.21; Ctrl: Milk 40.26 ± 8.27 Yoghurt: 43.19 ± 7.21 | Int: Milk 22.95 ± 2.96 Yoghurt: 23.8 ± 3.65 Ctrl: Milk 23.11 ± 3.16 Yoghurt: 23.27 ± 3.27 | NA | Vit D3-fortified low-fat milk and Vit D3-fortified low-fat yoghurt; Milk: 37.5 Yoghurt: 37.5 | Milk: 35.2 ± 12.875 Yoghurt: 35.35 ± 12.6 | Milk: 47.75 ± 14.225 Yoghurt: 52.2 ± 14.4 | Unfortified low-fat milk and yoghurt | Milk: 35.05 ± 12.9 Yoghurt: 38.35 ± 14.2 | Milk: 34.725 ± 14.625 Yoghurt: 36.175 ± 9.825 |

| Nikooyeh et al. (2011) [33] | Iran | 30; 30 | 12 weeks; autumn and winter | T2DM patient | 50.7 ± 6.1 | Int: 29.2 ± 4.4 Ctrl: 29.9 ± 4.7 | NA | Vit D3-fortified yoghurt drink; 25 | 25(OH)D3: 44.4 ± 28.7 | 25(OH)D3: 77.7 ± 28.6 | Plain yoghurt | 25(OH)D3: 41.6 ± 44.5 | 25(OH)D3: 37.2 ± 44 |

| Wagner et al. (2008) [62] | Canada | DC: 20 DLF: 10; 10 | 8 weeks; winter | Healthy | DC: 28.7 ± 11.4 DLF: 30.6 ± 11.7 | DC: 25.2 ± 5.0 DLF: 24.2 ± 3.3 | NA | DC: Vit D3-fortified regular-fat cheddar cheese DLF: Vit D3-fortified low-fat cheddar cheese; DC: 100 DLF: 100 | DC: 50.7 ± 18.9 DLF: 57.5 ± 18.4 | DC: 65.3 ± 24.1 DLF: 69.4 ± 21.7 | Unfortified cheddar cheese | 55.0 ± 25.3 | 50.7 ± 24.2 |

| Taghizadeh et al. (2021) [48] | Iran | MetS−: 39 MetS+: 28; MetS−: 39 MetS+: 33 | 10 weeks; winter | With MetS and without MetS | MetS−: 9.67 ± 7.15 MetS+: 1.6 ± 8.2 | MetS−: 2.87 ± 3.12 MetS+: 4.72 ± 3.25 | NA | Vit D-fortified yoghurt; 37.5 | MetS−: 34.925 ± 10.675 MetS+: 36.175 ± 15.175 | MetS−: 51.75 ± 12.925 MetS+: 53.475 ± 16.35 | Plain yoghurt | MetS−: 38.75 ± 14.175 MetS+: 38.125 ± 14.55 | MetS−: 35.5 ± 9.975 MetS+: 36.75 ± 9.825 |

| Ganmaa et al. (2017) [42] | Mongolia | 138; 97 | 7 weeks; winter | Healthy | Int: 10.0 ± 0.8 Ctrl: 9.7 ± 0.9 | Int: 16.4 ± 1.9 Ctrl: 16.3 ± 1.8 | Mongol | Vit D-fortified cow’s milk; 7.52 | 19.25 ± 10 | 49.25 ± 15.25 | Unfortified cow’s milk | 18 ± 9.5 | 18.75 ± 9 |

| Sharifan et al. (2024) [51] | Iran | PSST score <19: 31 19–28:18 >28: 22; PSST score <19: 26 19–28:27 >28: 27 | 10 weeks; winter | Abdominal obesity | Int: PSST <19: 43.26 ± 7.94 19–28: 41.52 ± 8.15 >28: 38.75 ± 5.37 Ctrl: PSST <19: 42.34 ± 7.13 19–28: 41.33 ± 9.22 >28: 39.01 ± 4.44 | NA | NA | Vit D3-fortified low-fat milk and vit D3-fortified low-fat yoghurt; Milk: 37.5 Yoghurt: 37.5 | PSST score: <19: 35.25 ± 14.875 19–28: 35.8 ± 11.3 >28: 39.025 ± 11.7 | PSST score: <19: 49.85 ± 16.525 19–28: 52.9 ± 13.075 >28: 52.525 ± 11.45 | Unfortified low-fat milk and yoghurt | PSST score: <19: 42.825 ± 12 19–28: 41.875 ± 11.375 >28: 35.85 ± 15.125 | PSST score: <19: 40.25 ± 11.1 19–28: 40.85 ± 11.75 >28: 35.5 ± 16.7 |

| Johnson et al. (2005) [61] | US | 35; 37 | 2 months; Winter | Healthy | ≥60 | NA | NA | Vit D3-fortified process cheese; 15 | 57.5 ± 3.5 | 52.5 ± 3.5 | Unfortified cheese | 50 ± 3.0 | 55 ± 2.75 |

| Shab-Bidar et al. (2011) [34] | Iran | 50; 50 | 12 weeks; Autumn to winter | T2DM patient | 52.5 ± 7.4 | Int: 28.6 ± 4.0 Ctrl: 30.0 ± 4.2 | NA | Vit D3-fortified doogh **; 25 | 38.5 ± 20.2 | 72.0 ± 23.5 | Plain doogh ** | 38.0 ± 22.8 | 33.4 ± 22.8 |

| Neyestani et al. (2012) [35] | Iran | 30; 30 | 12 weeks; autumn and winter | T2DM patient | Int: 51.5 ± 5.4 Ctrl: 50.8 ± 6.7 | Int: 29.2 ± 4.4 Ctrl: 29.9 ± 4.7 | NA | Vit D3-fortified doogh **; 25 | 44.4 ± 28.7 | 77.7 ± 28.6 | Plain doogh ** | 41.6 ± 44.5 | 37.2 ± 44 |

| Bonjour et al. (2013) [56] | France | 32; 27 | 56 days; Winter | Healthy | Int: 85.8 ± 1.2 Ctrl: 85.1 ± 1.3 | Int: 26.2 ± 0.7 Ctrl: 26.6 ± 1.0 | NA | Vit D3-fortified yoghurt (with 800 mg of Ca); 20 | 19.2 ± 1.2 | 39.5 ± 3.3 | Yoghurt (fortified with 280 mg of calcium only) | 16.2 ± 0.6 | 21.4 ± 2.7 |

| Jafari et al. (2016) [39] | Iran | 30; 29 | 12 weeks; late autumn to winter | T2DM patient, postmenopausal | Int: 57.8 ± 5.5 Ctrl: 56.8 ± 5.7 | Int: 28.00 ± 0.82 Ctrl: 29.30 ± 0.72 | Iranian | Vit D-fortified yoghurt; 50 | 62.23 ± 4.52 | 86.83 ± 4.87 | Plain yoghurt | 62.72 ± 4.27 | 56.13 ± 2.89 |

| Li and Xing (2016) [41] | China | 48; 49 | 16 weeks; Winter | Women with GDM | 24–32 | Int: 24.61 Ctrl: 25.5 | Chinese | Vit D3-fortified yoghurt; 25 | 42 ± 11.5 | 73.75 ± 14.23 | Plain yoghurt | 40.5 ± 8.5 | 39.75 ± 11.25 |

| Hajimohammadi et al. (2017) [43] | Iran | 50; 50 | 12 weeks; NA | T2DM patient | Int: 52.4 ± 8.4 Ctrl: 52.6 ± 6.3 | Int: 28.6 ± 4.0 Ctrl: 30.0 ± 4.2 | Iranian | Vit D-fortified yoghurt drink; 25 | 38.5 ± 20.2 | 72.0 ± 23.5 | Unfortified yoghurt drink | 38.0 ± 22.8 | 33.4 ± 22.8 |

| Manios et al. (2017) [59] | Greece | 40; 39 | 8 weeks; Winter | Postmenopausal women | Int: 62.6 ± 6.0 Ctrl: 63.2 ± 5.9 | Int: 28.0 ± 3.8 Ctrl: 29.0 ± 2.9 | NA | Vit D3-fortified Gouda-type cheese (fat reduced); 5.7 | 47.3 ± 15.2 | 52.5 ± 12.0 | Unfortified, fat-reduced Gouda-type cheese | 42.9 ± 17.7 | 38.3 ± 18.9 |

| Brett et al. (2018) [28] | Canada | 26; 25 | 6 months; autumn to spring | Healthy | Int: 5.0 ± 1.8 Ctrl: 5.4 ± 2.0 | z score: Int: 0.55 ± 0.98 Ctrl: 0.81 ± 0.88 | White: Int: n = 18 Ctrl: n = 13 | Vit D3-fortified cheddar cheese and Vit D3-fortified yoghurt; 15 | 25(OH)D3: 65.3 ± 12.2 | 25(OH)D3: At 3 months, 64.7 ± 12.2 At 6 months: 58.4 ± 8.7 | Unfortified cheddar cheese or drinkable yoghurts | 25(OH)D3: 67.5 ± 15.1 | 25(OH)D3: At 3 months: 58.3 ± 15.3 At 6 months: 56.6 ± 13.9 |

| Mohammadi-Sartang et al. (2018) [45] | Iran | 44; 43 | 10 weeks; NA | With MetS | Int: 45.4 ± 8.9 Ctrl: 45.6 ± 8.7 | Int: 30.1 ± 2.6 Ctrl: 30.8 ± 2.2 | NA | Vit D3-fortified yoghurt (with calcium and inulin); 25 | 65.1 ± 34.9 | 98.6 ± 28.8 | Plain yoghurt | 65.2 ± 32.6 | 70.2 ± 32.6 |

| Shab-Bidar et al. (2015) [38] | Iran | 31; 29 | 12 weeks; NA | Fasting blood glucose > 7 mmol/L | Int: 54.1 ± 8 Ctrl: 51.3 ± 7.7 | NA | Iranian | Vit D-fortified doogh ** (with 170 mg calcium) | 41.6 ± 15.9 | 77.1 ± 19.7 | Unfortified doogh ** (170 mg Calcium) | 41.1 ± 20.5 | 36.2 ± 23.6 |

| Moreira-Lucas et al. (2016) [63] | Canada | 35; 36 | 24 weeks; NA | With serum 25(OH)D ≤ 65 nmol/L, impaired fasting glucose and elevated glycated haemoglobin | Int: 49.1 ± 13.9 Ctrl: 45.6 ± 14.3 | Int: 30.1 ± 3.9 Ctrl: 31.7 ± 4.9 | White: Int n = 12 Ctrl n = 19 | Vit D3-fortified low-fat cheddar cheese; 100 | 48.1 ± 14.3 | 98.7 ± 37.1 | Unfortified low-fat cheddar cheese | 47.6 ± 14.3 | 45.5 ± 14.3 |

| Keane et al. (1992) [52] | Ireland | 39; 39 | 3 months; NA | Elderly long-stay patients | Int: 85 Ctrl: 84 | NA | NA | Vit D-fortified milk; 5 | 6.0 ± 6.4 3 | 37.0 ± 23.1 3 | Unfortified milk | 7.8 ± 9.2 3 | 17.5 ± 11.2 3 |

| Nikooyeh et al. (2023) [49] | Iran | 27; 27 | 8–12 weeks; Autumn and winter | T2DM patient | Int 45.0 ± 5.6 Ctrl: 44.1 ± 6.6 | Int: 28.4 ± 4.0 Ctrl: 28.2 ± 3.7 | NA | Vit D-fortified yoghurt drink; 25 | 39.7 ± 13.6 | 70.6 ± 19.2 | Unfortified yoghurt drink | 36.9 ± 18.9 | 32.9 ± 25.2 |

| Sharifan et al. (2023) [50] | Iran | Int: Milk: 73 Yoghurt: 69; Ctrl: Milk: 73 Yoghurt: 74 | 10 weeks; winter | Abdominally obese | Int: Milk 40.42 ± 8.03 Yoghurt: 43.47 ± 7.21; Ctrl: Milk 40.26 ± 8.27 Yoghurt: 43.19 ± 7.21 | Int: Milk 22.95 ± 2.96 Yoghurt: 23.8 ± 3.65 Ctrl: Milk 23.11 ± 3.16 Yoghurt: 23.27 ± 3.27 | NA | Vit D3-fortified milk and Vit D3-fortified yoghurt; Milk and yoghurt: 37.5 | Milk: 34.675 ± 13.05 Yoghurt: 35.5 ± 12.625 | Milk: 47.825 ± 14.5 Yoghurt: 52.775 ± 14.225 | Plain milk and yoghurt | Milk: 35.65 ± 12.6 Yoghurt: 38.55 ± 14.35 | Milk: 35.4 ± 14.225 Yoghurt: 36.175 ± 9.925 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, C.L.; Givens, D.I.; Turpeinen, A.M.; Liu, X.; Guo, J. Is Vitamin D Fortification of Dairy Products Effective for Improving Vitamin D Status? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3757. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233757

Wong CL, Givens DI, Turpeinen AM, Liu X, Guo J. Is Vitamin D Fortification of Dairy Products Effective for Improving Vitamin D Status? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3757. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233757

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Cheuk Lun, D. Ian Givens, Anu M. Turpeinen, Xinyue Liu, and Jing Guo. 2025. "Is Vitamin D Fortification of Dairy Products Effective for Improving Vitamin D Status? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3757. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233757

APA StyleWong, C. L., Givens, D. I., Turpeinen, A. M., Liu, X., & Guo, J. (2025). Is Vitamin D Fortification of Dairy Products Effective for Improving Vitamin D Status? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients, 17(23), 3757. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233757