Highly Processed Food and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: The Preventive Challenge—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection Process

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

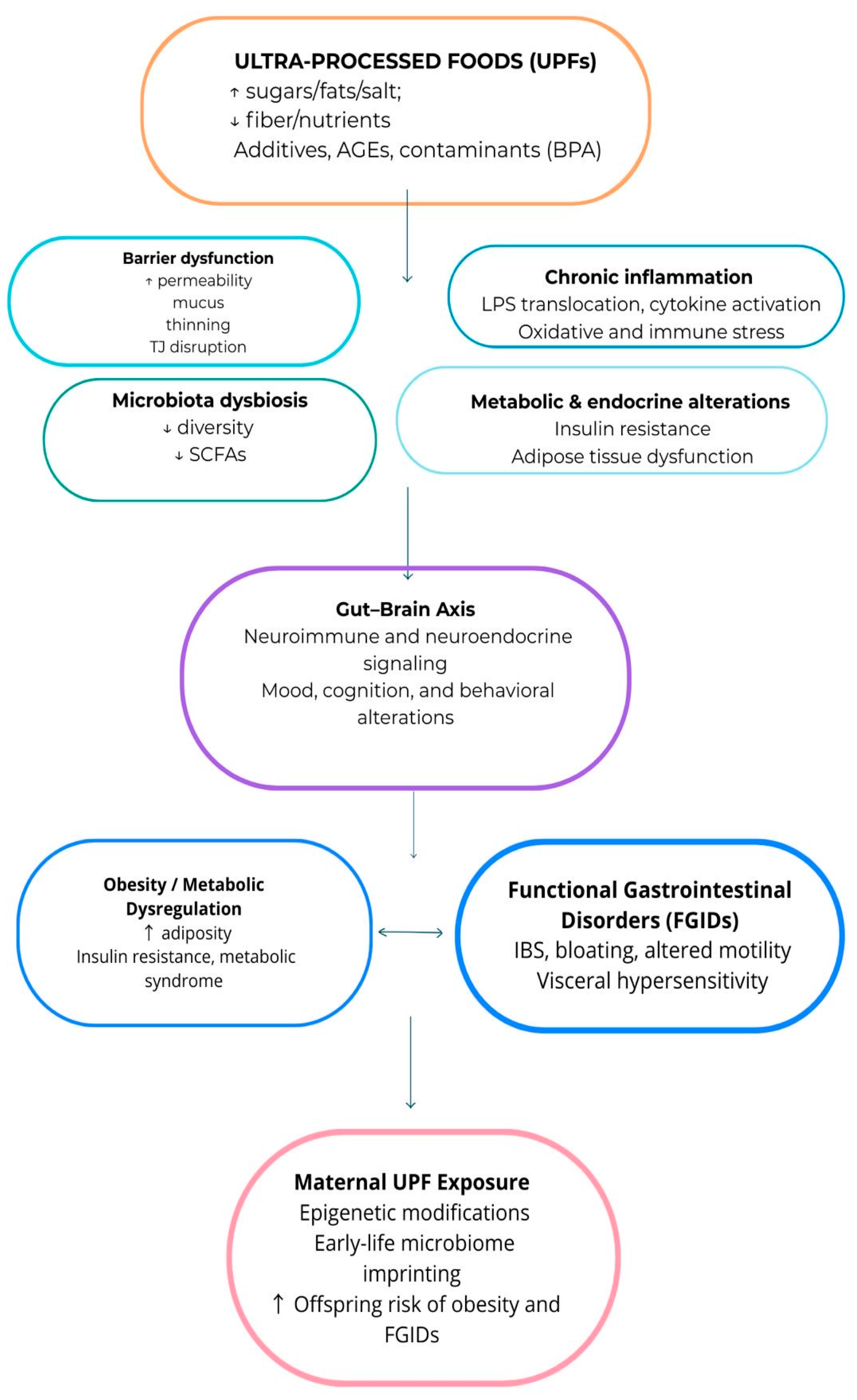

3.1. Ultra-Processed Foods

3.1.1. UPF Classification Systems

3.1.2. Dietary Patterns and Nutrient Deficiency Issues

3.2. Pediatric Obesity and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

3.2.1. Epidemiology of Pediatric Obesity

3.2.2. Pediatric FGIDs: Definitions and Prevalence

3.2.3. Association Between Obesity and FGIDs

3.2.4. Mechanisms Linking Obesity to FGIDs

3.3. Relationship Between UPF and FGIDs

4. Prevention and Management Strategies

5. Future Perspectives

6. Limitations of the Reviewed Studies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calcaterra, V.; Cena, H.; Loperfido, F.; Porri, D.; Basilico, S.; Gazzola, C.; Ricciardi Rizzo, C.; Conti, M.V.; Luppino, G.; Wasniewska, M.G.; et al. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and Childhood Obesity: The Role of Diet and Its Impact on Microbiota. Nutrients 2024, 17, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth, L.; Machado, P.; Zinöcker, M.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M. Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridi, E.; Karatzi, K.; Magriplis, E.; Charidemou, E.; Philippou, E.; Zampelas, A. The Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Obesity and Cardiometabolic Comorbidities in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 82, 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mescoloto, S.B.; Pongiluppi, G.; Domene, S.M.Á. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Children and Adolescents’ Health. J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, S18–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaFata, E.M.; Allison, K.C.; Audrain-McGovern, J.; Forman, E.M. Ultra-Processed Food Addiction: A Research Update. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesan, A.; Kamila, G.; Gulati, S. Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. J. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2024, 2, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyak, U.; Urganci, N.; Usta, M. Assesment of Functional Gastrointestinal Diseases in Obese Children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 4949–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgio, V.; Margiotta, G.; Stella, G.; Di Cicco, F.; Leoni, C.; Proli, F.; Zampino, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Onesimo, R. Intestinal Permeability in Children with Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: The Effects of Diet. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashankar, D.S.; Loening-Baucke, V. Increased Prevalence of Obesity in Children with Functional Constipation Evaluated in an Academic Medical Center. Pediatrics 2005, 116, e377–e380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galai, T.; Moran-Lev, H.; Cohen, S.; Ben-Tov, A.; Levy, D.; Weintraub, Y.; Amir, A.; Segev, O.; Yerushalmy-Feler, A. Higher Prevalence of Obesity among Children with Functional Abdominal Pain Disorders. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambucci, R.; Quitadamo, P.; Ambrosi, M.; De Angelis, P.; Angelino, G.; Stagi, S.; Verrotti, A.; Staiano, A.; Farello, G. Association Between Obesity/Overweight and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyams, J.S.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Saps, M.; Shulman, R.J.; Staiano, A.; Van Tilburg, M. Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Child/Adolescent. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1456–1468.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ciaula, A.; Wang, D.Q.; Portincasa, P. Gallbladder and Gastric Motility in Obese Newborns, Pre-adolescents and Adults. J. Gastro Hepatol. 2012, 27, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, K.; Kim, N. Roles of Sex Hormones and Gender in the Gut Microbiota. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 27, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassaing, B.; Van de Wiele, T.; De Bodt, J.; Marzorati, M.; Gewirtz, A.T. Dietary Emulsifiers Directly Alter Human Microbiota Composition and Gene Expression Ex Vivo Potentiating Intestinal Inflammation. Gut 2017, 66, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Dang, Y. Roles of Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in Overweight and Obesity of Children. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 994930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Sierra, A.; Milagro, F.I.; Aranaz, P.; Martínez, J.A.; Riezu-Boj, J.I. Gut Microbiota Differences According to Ultra-Processed Food Consumption in a Spanish Population. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.; Moazzami, K.; Wittbrodt, M.; Nye, J.; Lima, B.; Gillespie, C.; Rapaport, M.; Pearce, B.; Shah, A.; Vaccarino, V. Diet, Stress and Mental Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinella, D.; Raoul, P.C.; Valeriani, E.; Venturini, I.; Cintoni, M.; Severino, A.; Galli, F.S.; Mora, V.; Mele, M.C.; Cammarota, G.; et al. The Detrimental Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on the Human Gut Microbiome and Gut Barrier. Nutrients 2025, 17, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perler, B.K.; Friedman, E.S.; Wu, G.D. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in the Relationship Between Diet and Human Health. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2023, 85, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Sierra, A.; Ramos-Lopez, O.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Milagro, F.I.; Martinez, J.A. Diet, Gut Microbiota, and Obesity: Links with Host Genetics and Epigenetics and Potential Applications. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S17–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz, J. Nutrition, Microbiota and Noncommunicable Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, F.; Magkos, F.; Fava, F.; Milani, G.P.; Agostoni, C.; Astrup, A.; Saguy, I.S. A Multidisciplinary Perspective of Ultra-Processed Foods and Associated Food Processing Technologies: A View of the Sustainable Road Ahead. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Puppo, F.; Del Bo’, C.; Vinelli, V.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M.; Martini, D. A Systematic Review of Worldwide Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods: Findings and Criticisms. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimani, N.; Deharveng, G.; Southgate, D.A.T.; Biessy, C.; Chajès, V.; Van Bakel, M.M.E.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; McTaggart, A.; Grioni, S.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; et al. Contribution of Highly Industrially Processed Foods to the Nutrient Intakes and Patterns of Middle-Aged Populations in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, S206–S225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidou, S.; Christodoulou, A.; Fardet, A.; Frank, K. The Holistico-Reductionist Siga Classification According to the Degree of Food Processing: An Evaluation of Ultra-Processed Foods in French Supermarkets. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 2026–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, E.; Esposito, S.; Costanzo, S.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; De Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; Bonaccio, M. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Its Correlates among Italian Children, Adolescents and Adults from the Italian Nutrition & Health Survey (INHES) Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 6258–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okkio Alla SALUTE. Epicentro-ISS Istituto Superiore Di Sanità Sistema Di Sorveglianza; Higher Institute of Health: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: www.epicentro.iss.it/okkioallasalute (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Aramburu, A.; Alvarado-Gamarra, G.; Cornejo, R.; Curi-Quinto, K.; Díaz-Parra, C.D.P.; Rojas-Limache, G.; Lanata, C.F. Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption and Health-Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1421728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Qiu, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, J.; Nie, J. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madalosso, M.M.; Martins, N.N.F.; Medeiros, B.M.; Rocha, L.L.; Mendes, L.L.; Schaan, B.D.; Cureau, F.V. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Brazilian Adolescents: Results from ERICA. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 77, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaha, N.D. Prevalence and Determinants of Unhealthy Food and Beverage Consumption Among Children Aged 6–23 Months in Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, E.M.D.A.; Bertoni, N.; Alves-Santos, N.H.; Carneiro, L.B.V.; Schincaglia, R.M.; Boccolini, C.S.; Castro, I.R.R.D.; Anjos, L.A.D.; Berti, T.L.; Kac, G.; et al. Minimum Dietary Diversity and Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods among Brazilian Children 6-23 Months of Age. Cad. Saúde Pública 2023, 39, e00081422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kulchar, R.J.; Khadka, N.; Smith, C.; Mukherjee, P.; Rizal, E.; Sokal-Gutierrez, K. Maternal–Child Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Informal Settlements in Mumbai, India. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmpourtzidou, A.; Boussetta, S.; Maccarini, B.; Al-Naqeb, G.; De Giuseppe, R.; D’Addezio, L.; Mistura, L.; Cena, H. Higher Dietary Species Richness Is Associated with Better Diet Quality in Adults: Results from the Italian IV-SCAI Survey. Food Res. Int. 2025, 221, 117483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIPO Mediation Rules. Available online: http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/rules (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Hamilton, H.A.; Chaput, J.-P. Movement Behaviours, Breakfast Consumption, and Fruit and Vegetable Intake among Adolescents. J. Act. Sedentary Sleep Behav. 2022, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugars Intake for Adults and Children. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/4be74f01-de93-4596-bbd1-02a97afb1221/content?utm_medium=email&utm_source=transaction (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Maldonado-Pereira, L.; Barnaba, C.; De Los Campos, G.; Medina-Meza, I.G. Evaluation of the Nutritional Quality of Ultra-processed Foods (Ready to Eat + Fast Food): Fatty Acids, Sugar, and Sodium. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 3659–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Amicis, R.; Mambrini, S.P.; Pellizzari, M.; Foppiani, A.; Bertoli, S.; Battezzati, A.; Leone, A. Ultra-Processed Foods and Obesity and Adiposity Parameters among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 2297–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handakas, E.; Chang, K.; Khandpur, N.; Vamos, E.P.; Millett, C.; Sassi, F.; Vineis, P.; Robinson, O. Metabolic Profiles of Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Their Role in Obesity Risk in British Children. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 2537–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Leung, A.K.C.; Wong, A.H.C.; Hon, K.L. Childhood Obesity: An Updated Review. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2024, 20, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebeile, H.; Kelly, A.S.; O’Malley, G.; Baur, L.A. Obesity in Children and Adolescents: Epidemiology, Causes, Assessment, and Management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kelly, A.S.; Armstrong, S.C.; Michalsky, M.P.; Fox, C.K. Obesity in Adolescents: A Review. JAMA 2024, 332, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, B. Epidemiology of Childhood Obesity in Europe. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2000, 159, S14–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förster, L.-J.; Vogel, M.; Stein, R.; Hilbert, A.; Breinker, J.L.; Böttcher, M.; Kiess, W.; Poulain, T. Mental Health in Children and Adolescents with Overweight or Obesity. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Latner, J.D. Stigma, Obesity, and the Health of the Nation’s Children. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quitadamo, P.; Buonavolontà, R.; Miele, E.; Masi, P.; Coccorullo, P.; Staiano, A. Total and Abdominal Obesity Are Risk Factors for Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms in Children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 55, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaunak, M.; Byrne, C.D.; Davis, N.; Afolabi, P.; Faust, S.N.; Davies, J.H. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Childhood Obesity. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koebnick, C.; Smith, N.; Black, M.H.; Porter, A.H.; Richie, B.A.; Hudson, S.; Gililland, D.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Longstreth, G.F. Pediatric Obesity and Gallstone Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 55, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, M.; Kułaga, Z.; Niewiadomska, O.; Jankowska, I.; Lebensztejn, D.; Więcek, S.; Socha, P. Are Children with Gallstone Disease More Overweight? Results of a Matched Case-Control Analysis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2023, 47, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devanarayana, N.M.; Rajindrajith, S. Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Children: Current Knowledge, Challenges and Opportunities. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2211–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitelbaum, J.E.; Sinha, P.; Micale, M.; Yeung, S.; Jaeger, J. Obesity Is Related to Multiple Functional Abdominal Diseases. J. Pediatr. 2009, 154, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla, S.; Wang, D.; Saps, M. Obesity Predicts Persistence of Pain in Children with Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajindrajith, S.; Devanarayana, N.M.; Benninga, M.A. Obesity and Functional Gastrointestinal Diseases in Children. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 20, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phatak, U.P.; Pashankar, D.S. Prevalence of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Obese and Overweight Children. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 1324–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, J.K.; Lenhart, A.; Yang, P.-L.; Heitkemper, M.M.; Baker, J.; Keefer, L.; Saps, M.; Cuff, C.; Hungria, G.; Videlock, E.J.; et al. Risk Factors for Abdominal Pain–Related Disorders of Gut–Brain Interaction in Adults and Children: A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 995–1023.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslick, G.D. Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Obesity: A Meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.N.; Zhang, K.; Xiong, Y.Y.; Liu, S. The Relationship between Functional Constipation and Overweight/Obesity in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 94, 1878–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicken, S.J.; Batterham, R.L. Ultra-Processed Food and Obesity: What Is the Evidence? Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2024, 13, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, O.; Goyal, M.K.; Gupta, A.; Batta, S.; Singh, A.; Goyal, P.; Mehta, V.; Sood, A. Self-Reported Food Triggers and Food Fears Impact Nutrient Intake and Quality of Life in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Functional Dyspepsia. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 85, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Steele, E.; Juul, F.; Neri, D.; Rauber, F.; Monteiro, C.A. Dietary Share of Ultra-Processed Foods and Metabolic Syndrome in the US Adult Population. Prev. Med. 2019, 125, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassaing, B.; Compher, C.; Bonhomme, B.; Liu, Q.; Tian, Y.; Walters, W.; Nessel, L.; Delaroque, C.; Hao, F.; Gershuni, V.; et al. Randomized Controlled-Feeding Study of Dietary Emulsifier Carboxymethylcellulose Reveals Detrimental Impacts on the Gut Microbiota and Metabolome. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, D.L.; Sintusek, P. Functional Constipation in Children: What Physicians Should Know. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 1261–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, S.J.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Gibson, P.R. Short-Chain Carbohydrates and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, A.; Preidis, G.A.; Shulman, R.; Kashyap, P.C. The Gut Microbiome in Adult and Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut Microbiota in Human Metabolic Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Jiao, F.-Y. Link between Childhood Obesity and Gut Microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 3560–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canakis, A.; Haroon, M.; Weber, H.C. Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Gut Microbiota. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2020, 27, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolte, L.A.; Vich Vila, A.; Imhann, F.; Collij, V.; Gacesa, R.; Peters, V.; Wijmenga, C.; Kurilshikov, A.; Campmans-Kuijpers, M.J.E.; Fu, J.; et al. Long-Term Dietary Patterns Are Associated with pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Features of the Gut Microbiome. Gut 2021, 70, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, W.; Alkhouri, R.; Baker, R.D.; Bard, J.E.; Quigley, E.M.; Baker, S.S. Structural Changes in the Gut Microbiome of Constipated Patients. Physiol. Genom. 2014, 46, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.C.F.; Lederman, H.M.; Fagundes-Neto, U.; de Morais, M.B. Breath Methane Associated with Slow Colonic Transit Time in Children with Chronic Constipation. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2005, 39, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaluri, A.; Jackson, M.; Valestin, J.; Rao, S.S.C. Methanogenic Flora Is Associated with Altered Colonic Transit but Not Stool Characteristics in Constipation without IBS. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1407–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanping, W.; Gao, X.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, M.; Liao, S.; Zhou, J.; Hao, J.; Jiang, G.; Lu, Y.; Qu, T.; et al. The Interaction between Obesity and Visceral Hypersensitivity. J. Gastro. Hepatol. 2023, 38, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut Microbiota, Intestinal Permeability, and Systemic Inflammation: A Narrative Review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, D.; Man, S.C.; Farcău, D. Anxiety and Depression in Children with Irritable Bowel Syndrome—A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, S.; Sharma, A. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children: What Is New? J. Paediatr. Child Health 2020, 56, 1724–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, J.S.; Silva, A.C.A.D.; Santos, B.L.B.D.; Reinaldo, T.S.; Oliveira, A.M.D.; Lima, R.S.P.; Torres-Leal, F.L.; Santos, A.A.D.; Silva, M.T.B.D. Physical Exercise as a Therapeutic Approach in Gastrointestinal Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Al-Ani, O.; Al-Ani, F. Children’s Behaviour and Childhood Obesity. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2024, 30, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driessen, L.M.; Jong, J.C.K.; Wijtzes, A.; De Vries, S.I.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Hofman, A.; Raat, H.; Moll, H.A. Preschool Physical Activity and Functional Constipation: The Generation R Study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 57, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, C.S. Eating Habits, Lifestyle and Intestinal Constipation in Children Aged Four to Seven Years. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 36, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alum, E.U. Circadian Nutrition and Obesity: Timing as a Nutritional Strategy. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, T.; Choudhury, S.; Taheri, S. The Relationships Among Sleep, Nutrition, and Obesity. Curr. Sleep. Med. Rep. 2015, 1, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reytor-González, C.; Simancas-Racines, D.; Román-Galeano, N.M.; Annunziata, G.; Galasso, M.; Zambrano-Villacres, R.; Verde, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Frias-Toral, E.; Barrea, L. Chrononutrition and Energy Balance: How Meal Timing and Circadian Rhythms Shape Weight Regulation and Metabolic Health. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Hasak, S.; Cassell, B.; Ciorba, M.A.; Vivio, E.E.; Kumar, M.; Gyawali, C.P.; Sayuk, G.S. Effects of Disturbed Sleep on Gastrointestinal and Somatic Pain Symptoms in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messa, R.M.; Benfica, M.A.; Ribeiro, L.F.P.; Williams, C.M.; Davidson, S.R.E.; Alves, E.S. The Effect of Total Sleep Deprivation on Autonomic Nervous System and Cortisol Responses to Acute Stressors in Healthy Individuals: A Systematic Review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2024, 168, 107114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haapala, E.A.; Leppänen, M.H.; Kosola, S.; Appelqvist-Schmidlechner, K.; Kraav, S.-L.; Jussila, J.J.; Tolmunen, T.; Lubans, D.R.; Eloranta, A.-M.; Schwab, U.; et al. Childhood Lifestyle Behaviors and Mental Health Symptoms in Adolescence. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2460012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-Processed Food Exposure and Adverse Health Outcomes: Umbrella Review of Epidemiological Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Ugalde, I.Y.; De Vocht, F.; Jago, R.; Adams, J.; Ong, K.K.; Forouhi, N.G.; Colombet, Z.; Ricardo, L.I.C.; Van Sluijs, E.; Toumpakari, Z. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption in UK Adolescents: Distribution, Trends, and Sociodemographic Correlates Using the National Diet and Nutrition Survey 2008/09 to 2018/19. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 2709–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, S.; Wu, S. Ultra-Processed Foods and Risk of All-Cause Mortality: An Updated Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Syst. Rev. 2025, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.M.; Buffarini, R.; Domingues, M.R.; Barros, F.C.L.F.; Silveira, M.F.D. Consumo de Alimentos Ultraprocessados Por Crianças de Uma Coorte de Nascimentos de Pelotas. Rev. Saúde Pública 2022, 56, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Du, M.; Khandpur, N.; Rossato, S.L.; Lo, C.-H.; VanEvery, H.; Kim, D.Y.; Zhang, F.F.; Chavarro, J.E.; et al. Maternal Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Subsequent Risk of Offspring Overweight or Obesity: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. BMJ 2022, 379, e071767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reales-Moreno, M.; Tonini, P.; Escorihuela, R.M.; Solanas, M.; Fernández-Barrés, S.; Romaguera, D.; Contreras-Rodríguez, O. Ultra-Processed Foods and Drinks Consumption Is Associated with Psychosocial Functioning in Adolescents. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, D.C.; Gupta, S.K. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition—The Highlights of 2021. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. nutr. 2022, 74, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Blanco, L.; de la O, V.; Santiago, S.; Pouso, A.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Martín-Calvo, N. High Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods Is Associated with Increased Risk of Micronutrient Inadequacy in Children: The SENDO Project. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 3537–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.F.D.; Conceição-Machado, M.E.P.D.; Costa, P.R.D.F.; Cunha, C.D.M.; Queiroz, V.A.D.O.; Santana, M.L.P.D.; Leite, L.D.O.; Assis, A.M.D.O. Degree of Food Processing and Association with Overweight and Abdominal Obesity in Adolescents. Einstein 2022, 20, eAO6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, K.; Bancil, A.S.; Lindsay, J.O.; Chassaing, B. Ultra-Processed Foods and Food Additives in Gut Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 406–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Cena, H.; Rossi, V.; Santero, S.; Bianchi, A.; Zuccotti, G. Ultra-Processed Food, Reward System and Childhood Obesity. Children 2023, 10, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Blanco, L.; De La O Pascual, V.; Berasaluce, A.; Moreno-Galarraga, L.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Martín-Calvo, N. Individual and Family Predictors of Ultra-Processed Food Consumption in Spanish Children: The SENDO Project. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicken, S.J.; Batterham, R.L.; Brown, A. Nutrients or Processing? An Analysis of Food and Drink Items from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey Based on Nutrient Content, the NOVA Classification and Front of Package Traffic Light Labelling. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 1619–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umano, G.R.; Bellone, S.; Buganza, R.; Calcaterra, V.; Corica, D.; De Sanctis, L.; Di Sessa, A.; Faienza, M.F.; Improda, N.; Licenziati, M.R.; et al. Early Roots of Childhood Obesity: Risk Factors, Mechanisms, and Prevention Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, I.; Berridge, K.C. ‘Liking’ and ‘Wanting’ in Eating and Food Reward: Brain Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Physiol. Behav. 2020, 227, 113152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, R.B.; Barata, M.F.; Leite, M.A.; Andrade, G.C. How and Why Ultra-Processed Foods Harm Human Health. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2024, 83, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; Buso, P.; Mata, A.; Abdelkarim, O.; Aly, M.; Pinilla, J.; Fernandez, A.; Mendez, R.; Alvarez, A.; Valdes, N.; et al. Understanding Consumer Food Choices & Promotion of Healthy and Sustainable Mediterranean Diet and Lifestyle in Children and Adolescents through Behavioural Change Actions: The DELICIOUS Project. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 75, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaught, K.; Sjepcevich, G. Rural Food Forward: An Appetite for Change. Aust. J. Rural Health 2025, 33, e70091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, F.; Dello Russo, M.; Formisano, A.; De Henauw, S.; Hebestreit, A.; Hunsberger, M.; Krogh, V.; Intemann, T.; Lissner, L.; Molnar, D.; et al. Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption and Diet Quality of European Children, Adolescents and Adults: Results from the I.Family Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 3031–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giuseppe, R.; Loperfido, F.; Cerbo, R.M.; Monti, M.C.; Civardi, E.; Garofoli, F.; Angelini, M.; Maccarini, B.; Sommella, E.; Campiglia, P.; et al. LIMIT: LIfestyle and Microbiome InTeraction Early Adiposity Rebound in Children, a Study Protocol. Metabolites 2022, 12, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesareo, M.; Sorgente, A.; Labra, M.; Palestini, P.; Sarcinelli, B.; Rossetti, M.; Lanz, M.; Moderato, P. The Effectiveness of Nudging Interventions to Promote Healthy Eating Choices: A Systematic Review and an Intervention among Italian University Students. Appetite 2022, 168, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, C.M.; Hardy-Johnson, P.L.; Inskip, H.M.; Morris, T.; Parsons, C.M.; Barrett, M.; Hanson, M.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Baird, J. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of School-Based Interventions with Health Education to Reduce Body Mass Index in Adolescents Aged 10 to 19 Years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basilico, S.; Conti, M.V.; Ardoino, I.; Breda, C.; Loperfido, F.; Orsini, F.; Fernandez, M.L.O.; Pierini, L.; Bonizzoni, S.C.; Modena, E.; et al. Lights and Shadows of a Primary School-Based Nutrition Education Program in Italy: Insights from the LIVELY Project. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lo, B.K.; Park, I.Y.; Bauer, K.W.; Davison, K.K.; Haines, J.; Coley, R.L. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Fathers’ Food Parenting Practices and Children’s Diets. Child. Dev. 2025, 96, 1718–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Rodrigues, A.M.; Padez, C.; Rodrigues, D.; Dos Santos, E.A.; Baptista, L.C.; Liz Martins, M.; Fernandes, H.M. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Its Association with Risk of Obesity, Sedentary Behaviors, and Well-Being in Adolescents. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konieczynski, E.M.; Sahni, S.; Jacques, P.F.; Naumova, E.N. Ultra-Processed Food and Frailty: Evidence from a Prospective Cohort Study and Implications for Future Research. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year) | Study Design/Population | Main Findings | Notes/Mechanistic Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teitelbaum et al. (2020) [54] | Cross-sectional, pediatric gastroenterology population n = 757 patients + 255 matched controls | 23% of children with functional constipation (FC) and 24.8% with IBS were obese—significantly higher than controls. | Indicates strong association between obesity and FGIDs, particularly FC and IBS. |

| Galai et al. (2020) [10] | Cross-sectional, adolescents n = 173 patients | 39.5% of adolescents with functional abdominal pain (FAP) were overweight or obese, compared to 30% of controls. | Suggests excess weight may predispose to abdominal pain syndromes. |

| Tambucci et al. (2019) [11] | Observational, children/adolescents n = 103 patients + 115 matched controls | FGIDs were more common in youths with obesity (47.6%) than in normal-weight peers (17.4%). FC, FD, and IBS more frequent in obese group. | Highlights differential prevalence of FGID subtypes by weight status. |

| Phatak et al. (2014) [57] | Cross-sectional, school-age children n = 450 children (191 with obesity/overweight and 259 normal weight) | Overall prevalence of FGIDs: 16.1% in overweight/obese vs. 6.9% in normal-weight children. | Nearly half of obese children had ≥1 FGID, showing frequent coexistence of these conditions. |

| Zia JK et al. (2023) [58] | Systematic review n = 348 studies | Confirmed consistent link between obesity and FGIDs, particularly constipation; less consistent for IBS. | Suggests overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms involving gut motility and diet. |

| Eslick et al. (2012) [59] | Meta-analysis, adults n = 21 studies | Obesity associated with multiple GI symptoms, especially upper-abdominal symptoms (reflux, bloating). | Indicates similar trends across age groups; shared metabolic and mechanical mechanisms. |

| Bonilla et al. (2011) [55] | Prospective cohort study n = 188 patients | Obesity is associated with poor outcome and disability at long-term follow-up in children with abdominal pain-related FGIDs. | Highlights a strong association between persistence of GI symptoms at long-term follow-up and obesity and evidences that obese patients experienced higher intensity and frequency of FAP in patients without obesity. |

| Author (Year) | Study Design/Population | Main Findings | Mechanistic Insights/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cuevas-Sierra et al. (2019) [21] | Cross-sectional, adults (Spain, n = 186) | Higher UPF intake (>5 servings/day) associated with altered gut microbiota composition. | Reduced microbial diversity; sex-related differences; potential link with GI symptoms. |

| Mescoloto et al. (2024) [4] | Review, global pediatric data | UPFs provide 40–60% of daily energy in youth; correlated with obesity and GI discomfort. | Diets low in fiber and high in additives predispose to dysbiosis and inflammation. |

| Petridi et al. (2024) [3] | Systematic review (17 studies, children/adolescents) | 14 studies reported positive association between UPFs and overweight/obesity; FGIDs frequently co-occur. | Suggests common pathways via microbiota disruption and low-grade inflammation. |

| Reales-Moreno M. et al. (2022) [94] | Observational study; adolescents (n = 560) | High UPF consumption correlates with greater GI symptom burden and psychosocial impairment. | Suggests involvement of the gut–brain axis in diet-related FGID manifestations. |

| Belli D.C. & Gupta S.K. (2022) [95] | Narrative review summarizing key pediatric gastroenterology findings of 2021 | Highlights growing concern regarding UPF exposure in children due to its association with GI disturbances, obesity, and metabolic dysregulation. | Reinforces clinical relevance of diet–gut interactions, supporting UPFs as contributors to functional GI symptoms and broader digestive health burden in pediatrics. |

| García-Blanco L. et al. (2023) [96] | Prospective cohort study; 806 Spanish children (SENDO project) | High UPF consumption was associated with an increased risk of micronutrient inadequacy and poorer overall diet quality. | Nutrient deficiencies linked to UPF intake may impair gut barrier integrity and microbiota composition, favoring inflammation and functional GI disturbances. |

| Souza S.F. et al. (2022) [97] | Observational study; adolescents (n = 576) | UPF-rich diets correlate with abdominal obesity and GI symptoms. | Shared mechanisms include inflammation and microbiota dysbiosis. |

| Chen X. et al. (2020) [30] | Systematic review; general population (~334,114 participants total across studies) | UPF intake is consistently associated with GI complaints and functional symptoms. | Reduced microbial diversity, chronic inflammation, and increased gut permeability are key mechanisms. |

| De Amicis R. et al. (2022) [40] | Observational studies; children and adolescents | UPF intake is associated with GI dysfunction and metabolic alterations. | Combined effects on gut microbiota, barrier function, and systemic inflammation likely underlie FGIDs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calcaterra, V.; Cena, H.; Ferrara, C.; Magenes, V.C.; Boussetta, S.; Zambon, I.; Zuccotti, G. Highly Processed Food and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: The Preventive Challenge—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3744. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233744

Calcaterra V, Cena H, Ferrara C, Magenes VC, Boussetta S, Zambon I, Zuccotti G. Highly Processed Food and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: The Preventive Challenge—A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3744. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233744

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalcaterra, Valeria, Hellas Cena, Chiara Ferrara, Vittoria Carlotta Magenes, Sara Boussetta, Ilaria Zambon, and Gianvincenzo Zuccotti. 2025. "Highly Processed Food and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: The Preventive Challenge—A Narrative Review" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3744. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233744

APA StyleCalcaterra, V., Cena, H., Ferrara, C., Magenes, V. C., Boussetta, S., Zambon, I., & Zuccotti, G. (2025). Highly Processed Food and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: The Preventive Challenge—A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 17(23), 3744. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233744