Maternal Adiposity, Milk Production and Removal, and Infant Milk Intake During Established Lactation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Anthropometric and Body Composition Measurements

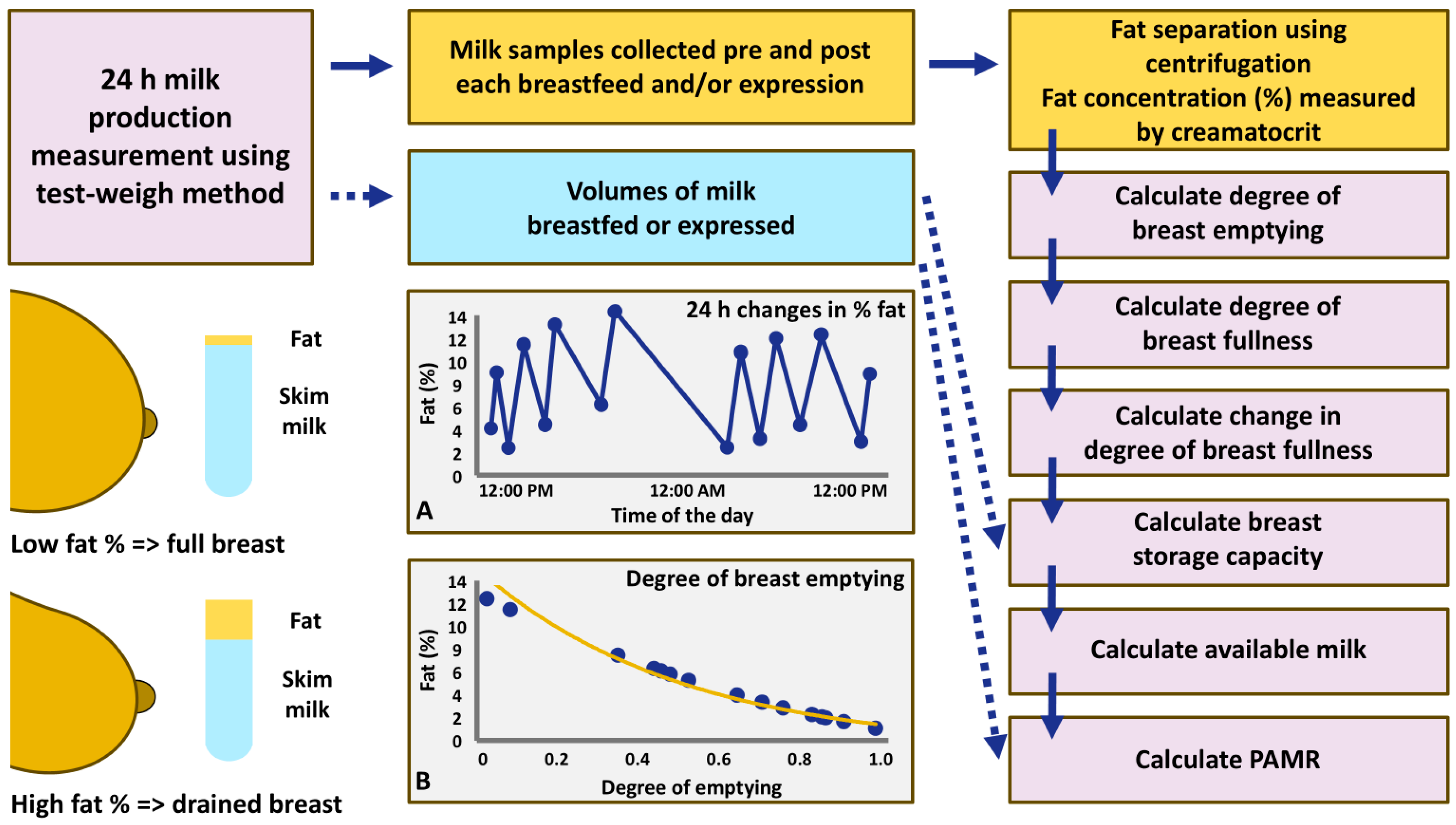

2.3. 24 h Milk Profile Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analyses

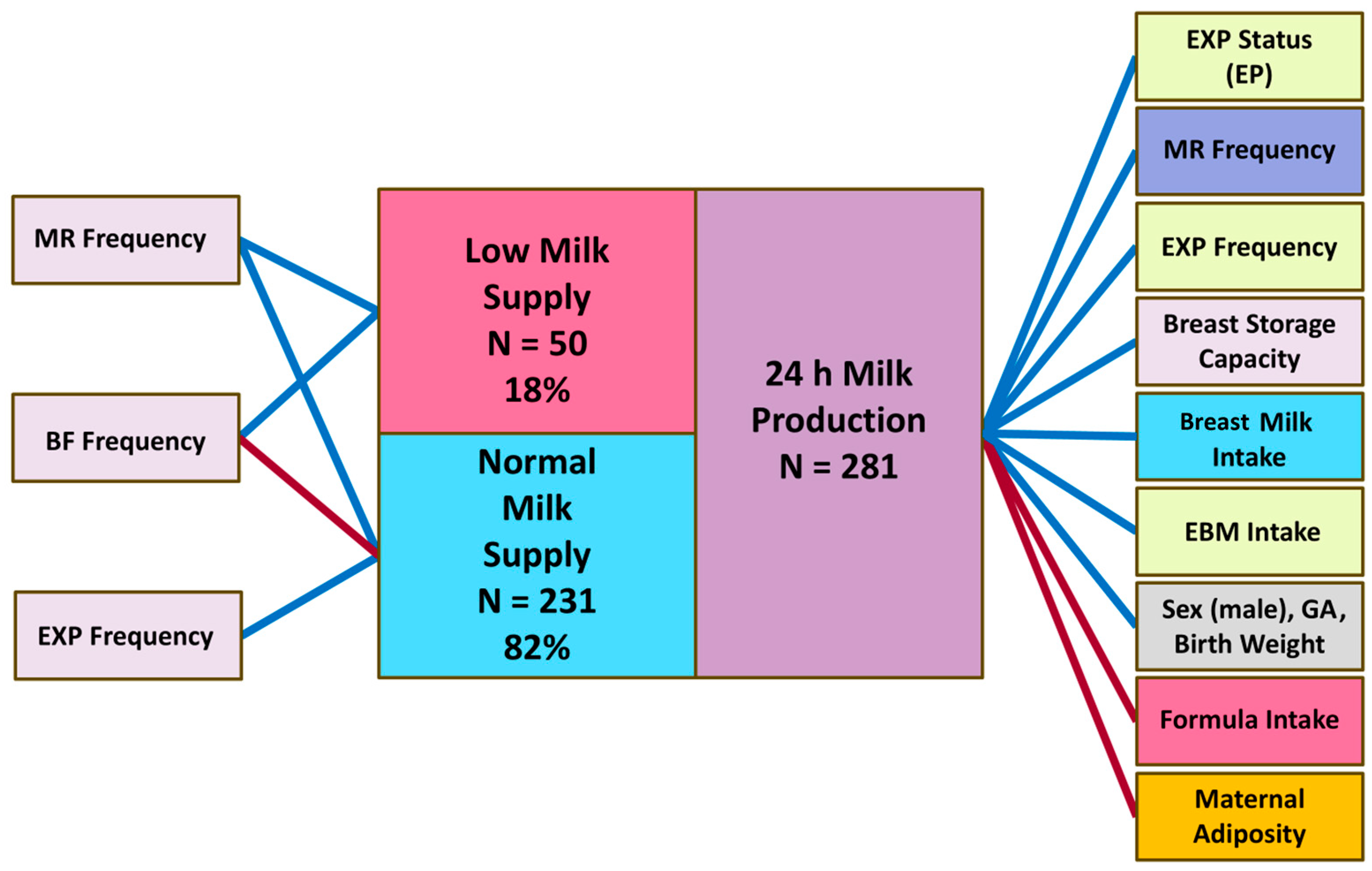

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographics and Body Composition

3.2. 24 h Milk Production Parameters, Breast Storage Capacity and PAMR

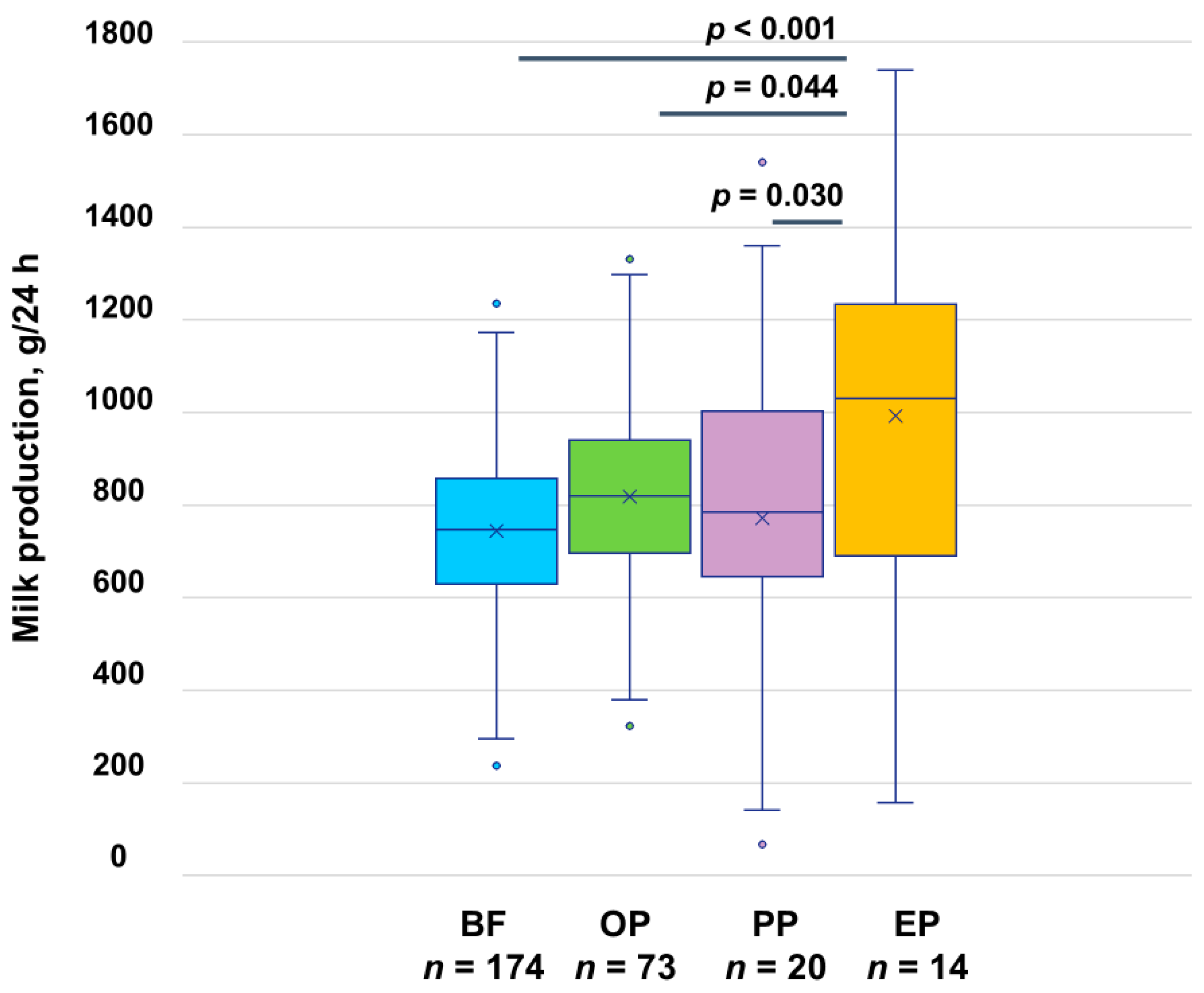

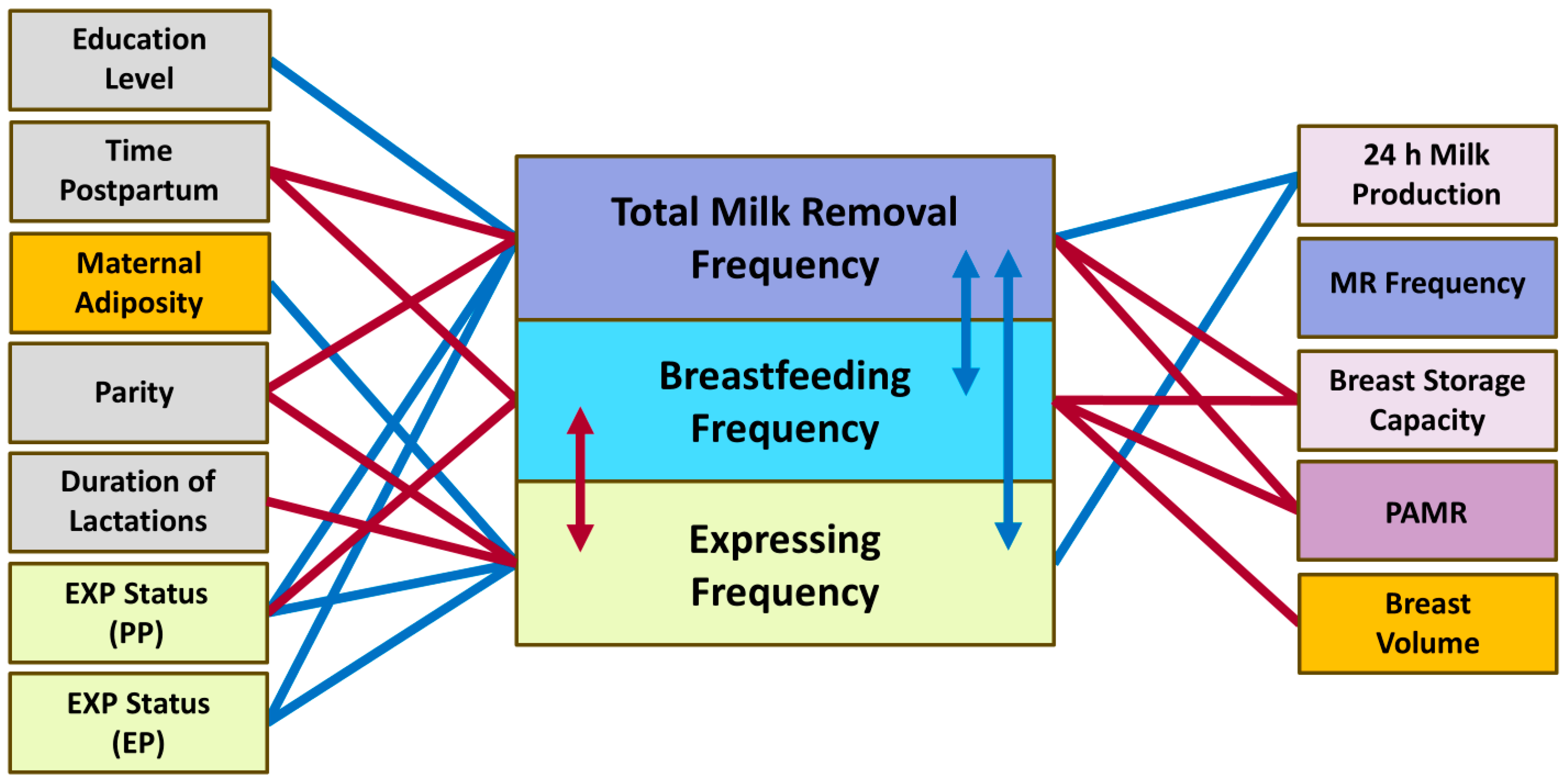

3.3. Milk Production

3.4. Infant Milk Intake

3.4.1. Breast Milk Intake

3.4.2. Expressed Breast Milk Intake

3.4.3. Commercial Milk Formula Intake

3.4.4. Total Milk Intake

3.5. Milk Removal Frequencies

3.5.1. Breastfeeding Frequency

3.5.2. Expressing Frequency

3.5.3. Milk Removal Frequency

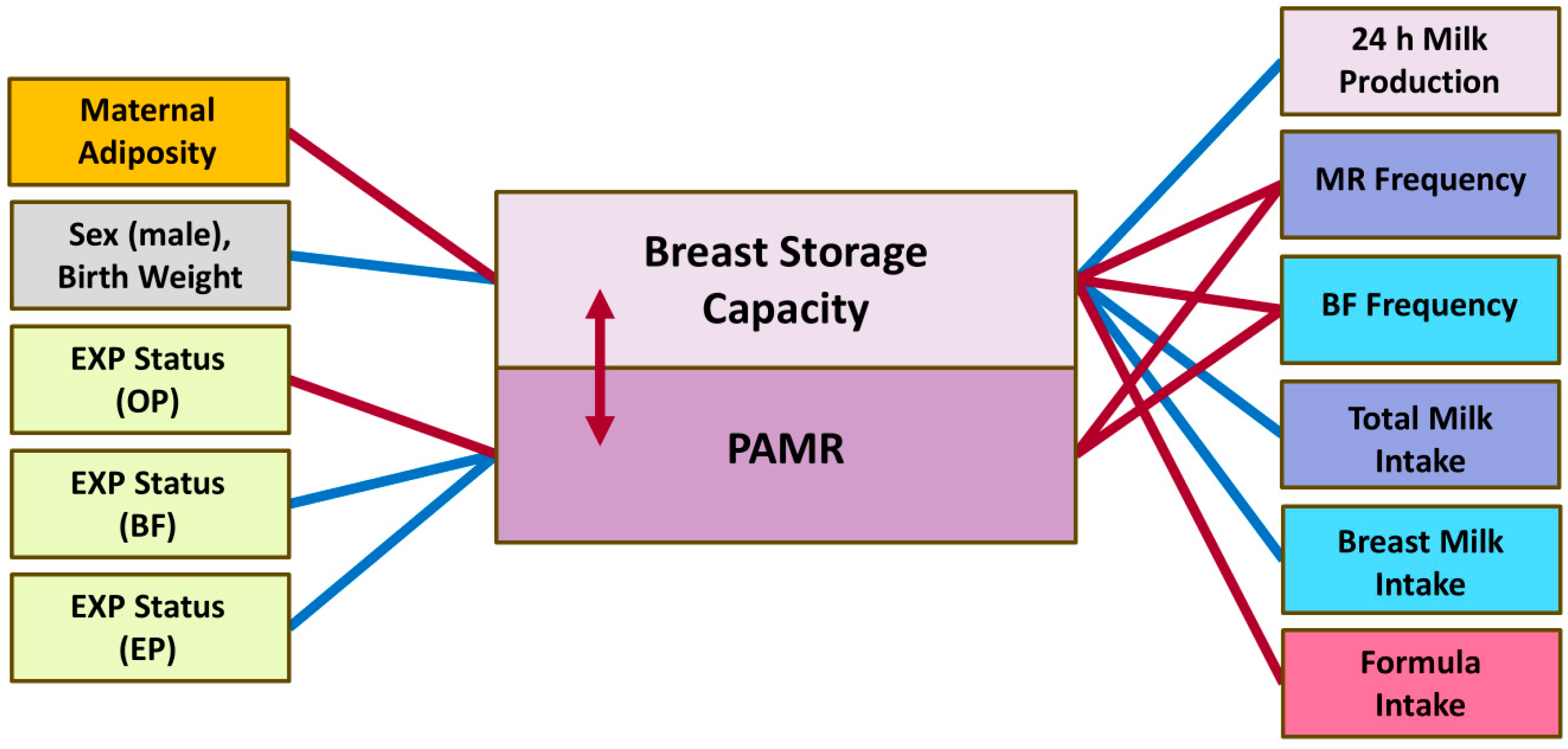

3.6. Breast Storage Capacity and PAMR

3.7. Breast Volume

4. Discussion

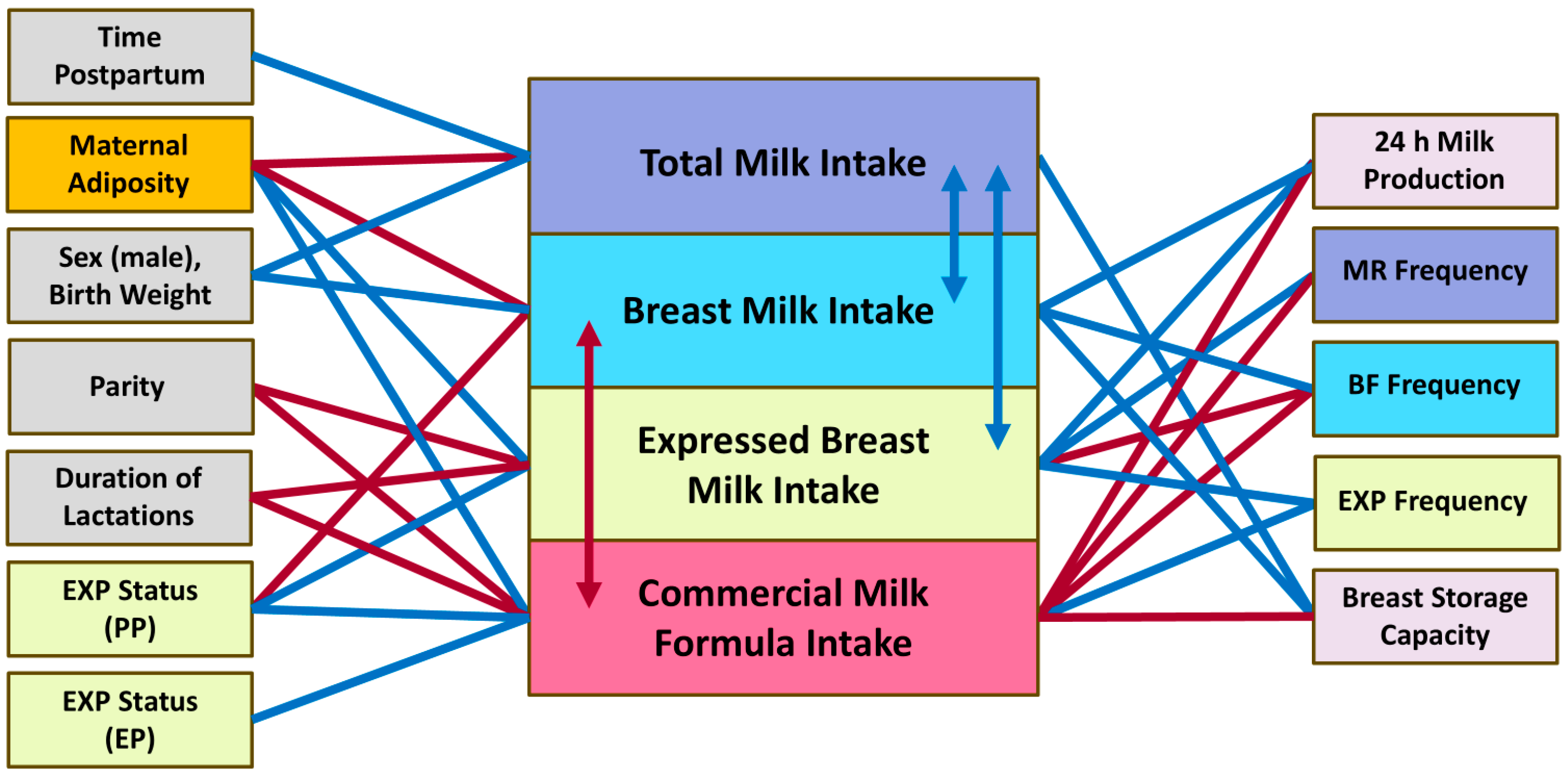

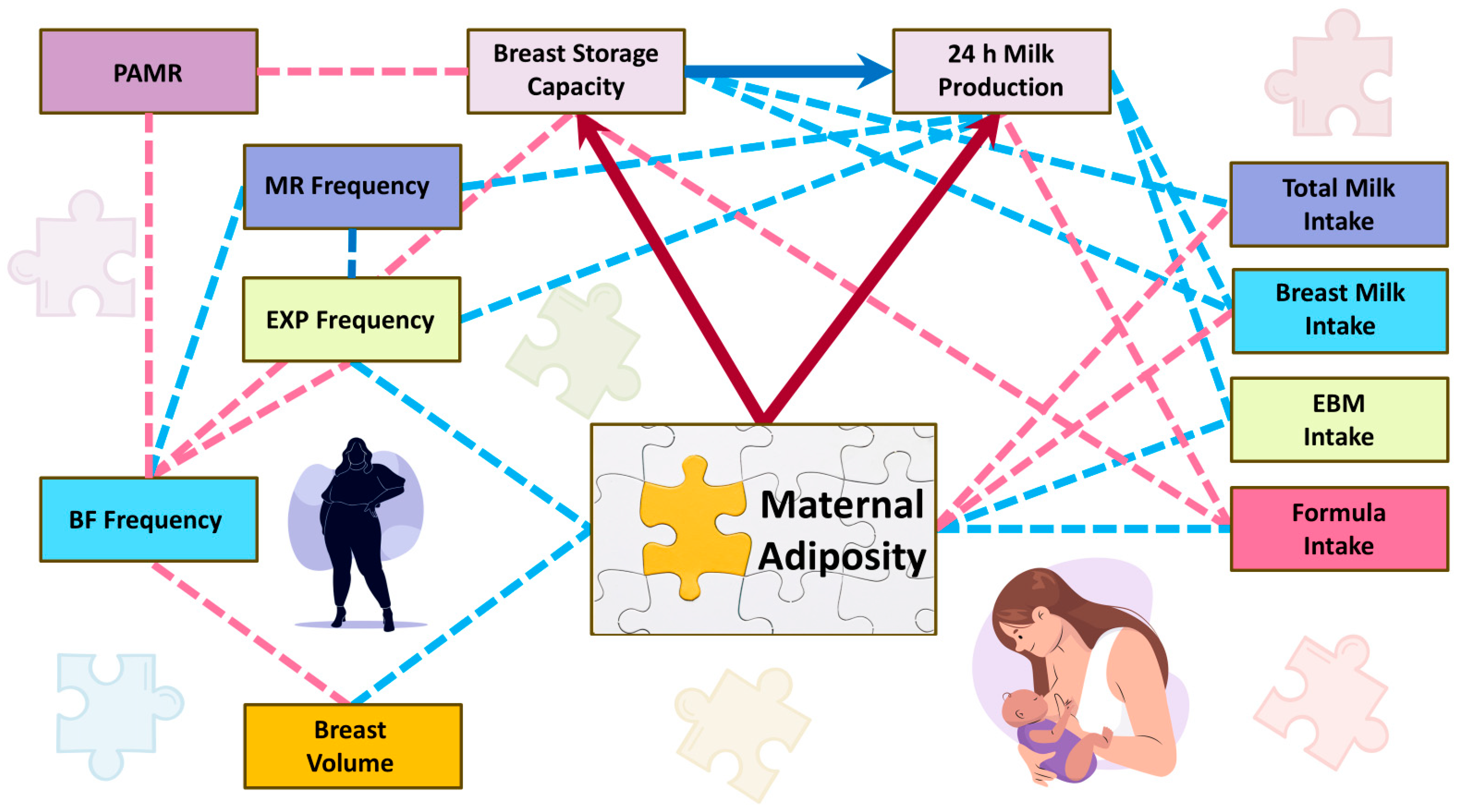

4.1. Milk Production, Milk Intake and Maternal Adiposity

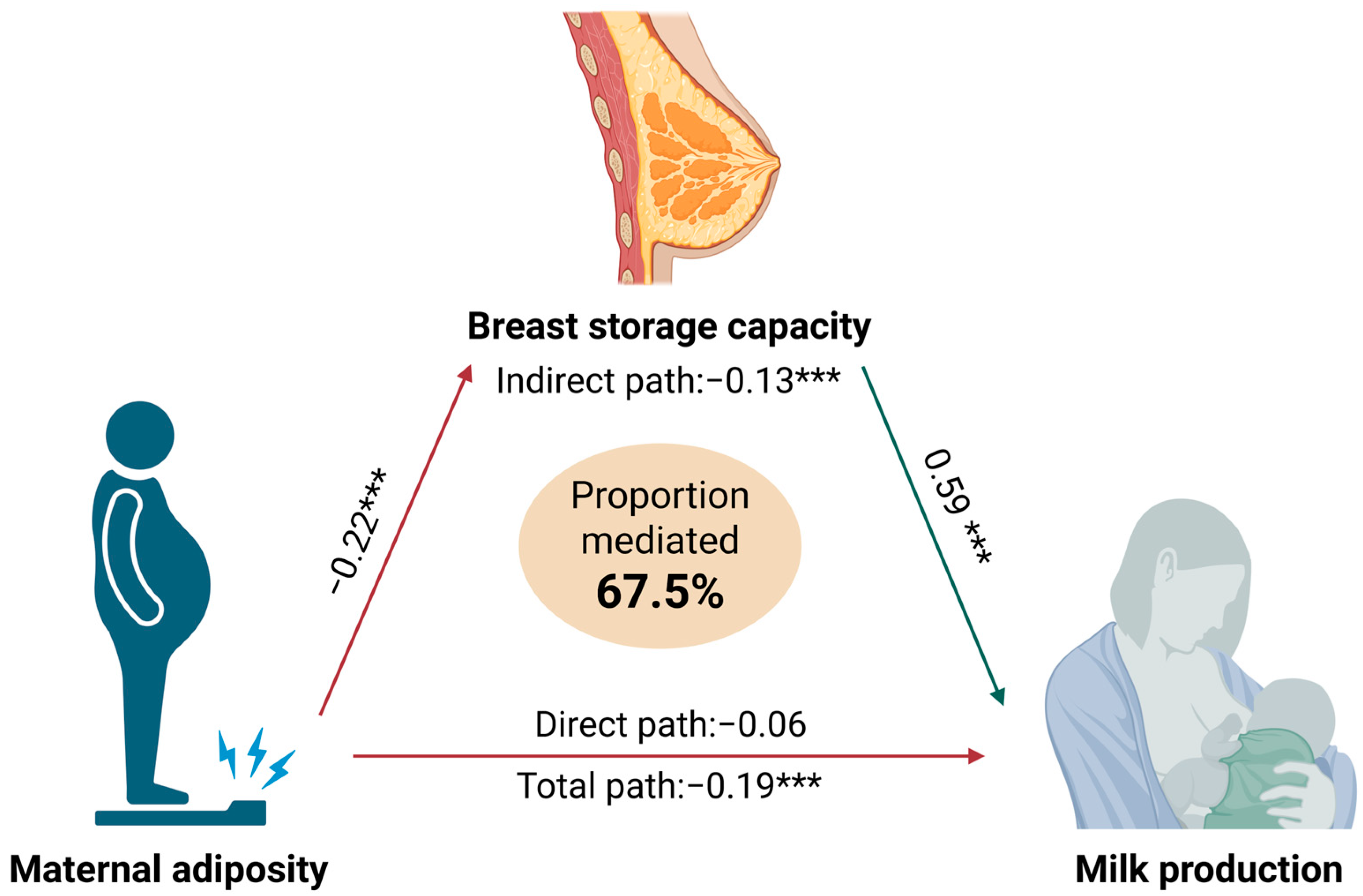

4.2. Breast Storage Capacity as a Mediator of Maternal Adiposity and Milk Production Relationships

4.3. Milk Removal Frequencies and Breast Storage Capacity

4.4. Expressing Status and Milk Removal Efficacy

4.5. Infant and Maternal Characteristics

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Breast Milk Intake 4 | Expressed Breast Milk Intake | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable Models | Adjusted Models | Univariable Models | Adjusted Models | |||||||

| Parameters (n = 281) | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | Birth Weight p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | Birth Weight p-Value |

| Time postpartum (months) | 19.07 ± 12.15 1 | 0.12 | 21.47 ± 11.91 2 | 0.073 | <0.001 | 5.53 ± 11.64 1 | 0.64 | 4.77 ± 11.65 2 | 0.68 | 0.25 |

| Birth mode 5 | NA | 0.46 | NA | 0.44 | <0.001 | NA | 0.31 | NA | 0.31 | 0.25 |

| Infant factors | ||||||||||

| Infant birth gestation (weeks) | 17.23 ± 11.46 | 0.13 | NA | NA | NA | −4.18 ± 10.98 | 0.70 | NA | NA | NA |

| Infant birth weight (g) | 98.30 ± 28.12 | <0.001 | NA | NA | NA | −32.58 ± 27.36 | 0.24 | NA | NA | NA |

| Infant sex (male) | 67.17 ± 24.59 | 0.007 | NA | NA | NA | 23.78 ± 23.75 | 0.32 | NA | NA | NA |

| Maternal factors | ||||||||||

| Maternal age (years) | −1.97 ± 2.97 | 0.51 | −1.92 ± 2.91 | 0.51 | <0.001 | −2.39 ± 2.83 | 0.40 | −2.41 ± 2.83 | 0.39 | 0.23 |

| Education level | NA | 0.89 | NA | 0.89 | <0.001 | NA | 0.10 | NA | 0.10 | 0.31 |

| Parity | 11.65 ± 15.84 | 0.46 | 5.75 ± 15.64 | 0.71 | <0.001 | −48.15 ± 14.86 | 0.001 | −46.73 ± 14.96 | 0.002 | 0.39 |

| Duration of previous lactations (months) | 1.98 ± 1.15 | 0.085 | 0.88 ± 1.16 | 0.45 | <0.001 | −3.00 ± 1.11 | 0.007 | −2.85 ± 1.15 | 0.014 | 0.63 |

| Breast volume (cm3) 6 | −0.0004 ± 0.04 | 0.99 | −0.01 ± 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.002 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 0.085 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.065 | 0.080 |

| Height (cm) | 3.37 ± 1.81 | 0.064 | 2.11 ± 1.82 | 0.25 | 0.002 | −1.19 ± 1.74 | 0.49 | −0.78 ± 1.78 | 0.66 | 0.29 |

| Weight (kg) | −1.53 ± 0.82 | 0.064 | −1.97 ± 0.81 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.23 ± 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.38 ± 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.21 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −7.15 ± 2.55 | 0.005 | −7.83 ± 2.49 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 1.17 ± 2.46 | 0.64 | 1.39 ± 2.47 | 0.58 | 0.22 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 0.26 ± 1.79 | 0.88 | −1.26 ± 1.81 | 0.49 | <0.001 | −1.84 ± 1.71 | 0.28 | −1.43 ± 1.76 | 0.42 | 0.34 |

| Fat-free mass index (kg/m2) | −5.12 ± 5.91 | 0.39 | −8.32 ± 5.85 | 0.16 | <0.001 | −5.33 ± 5.64 | 0.35 | −4.42 ± 5.70 | 0.44 | 0.29 |

| Fat mass (kg) | −3.86 ± 1.27 | 0.003 | −4.12 ± 1.24 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.53 ± 1.23 | 0.21 | 1.62 ± 1.23 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| Fat mass (%) | −7.21 ± 1.94 | <0.001 | −6.83 ± 1.91 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 3.74 ± 1.88 | 0.048 | 3.62 ± 1.88 | 0.056 | 0.28 |

| Fat mass index (kg/m2) | −13.41 ± 3.71 | <0.001 | −13.59 ± 3.63 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 4.79 ± 3.61 | 0.19 | 4.85 ± 3.61 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| Fat mass to fat-free mass ratio | −296.8 ± 73.9 | <0.001 | −282.5 ± 72.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 146.56 ± 72.03 | 0.043 | 141.98 ± 72.13 | 0.050 | 0.28 |

| 24 h milk production parameters | ||||||||||

| 24 h milk production (g) | 0.75 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.74 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.086 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.032 |

| Breastfeeding frequency 7 | 9.12 ± 2.96 | 0.002 | 8.54 ± 2.92 | 0.004 | <0.001 | −26.68 ± 2.39 | <0.001 | −26.57 ± 2.40 | <0.001 | 0.44 |

| Expressing frequency 7 | −6.18 ± 3.61 | 0.088 | −4.73 ± 3.57 | 0.19 | 0.001 | 47.85 ± 1.93 | <0.001 | 48.07 ± 1.95 | <0.001 | 0.36 |

| Milk removal frequency 7 | 5.62 ± 3.23 | 0.083 | 6.15 ± 3.16 | 0.053 | <0.001 | 7.37 ± 3.07 | 0.017 | 7.21 ± 3.07 | 0.019 | 0.28 |

| Mean breast storage capacity (g) 8 | 2.23 ± 0.20 | <0.001 | 2.14 ± 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.029 | −0.10 ± 0.29 | 0.72 | −0.07 ± 0.30 | 0.82 | 0.54 |

| Mean PAMR (%) 9 | 0.31 ± 1.10 | 0.78 | 0.18 ± 1.07 | 0.87 | <0.001 | 0.63 ± 1.25 | 0.62 | 0.66 ± 1.25 | 0.60 | 0.50 |

| Maternal expressing status | ||||||||||

| Expressing status | NA | 0.037 | NA | <0.001 | 0.002 | NA | <0.001 | NA | <0.001 | 0.81 |

| EP 10 vs. BF 11 | −96.25 ± 61.39 3 | 0.38 | −87.57 ± 60.43 | 0.45 | 0.002 | 678.51 ± 32.70 3 | <0.001 | 678.85 ± 32.79 | <0.001 | 0.81 |

| OP 12 vs. BF 11 | −16.57 ± 28.68 | 0.93 | −15.69 ± 28.21 | 0.94 | 0.002 | 81.00 ± 15.28 | <0.001 | 81.04 ± 15.30 | <0.001 | 0.81 |

| PP 13 vs. BF 11 | −126.18 ± 48.56 | 0.043 | −109.87 ± 48.03 | 0.094 | 0.002 | 412.93 ± 25.87 | <0.001 | 413.58 ± 26.06 | <0.001 | 0.81 |

| OP 12 vs. EP 10 | 79.68 ± 64.07 | 0.58 | 71.88 ± 63.06 | 0.65 | 0.002 | −597.51 ± 34.13 | <0.001 | −597.82 ± 34.21 | <0.001 | 0.81 |

| PP 13 vs. EP 10 | −29.93 ± 75.10 | 0.98 | −22.30 ± 73.90 | 0.99 | 0.002 | −265.58 ± 40.01 | <0.001 | −265.28 ± 40.09 | <0.001 | 0.81 |

| PP 13 vs. OP 12 | −109.62 ± 51.91 | 0.14 | −94.18 ± 51.28 | 0.24 | 0.002 | 331.92 ± 27.65 | <0.001 | 332.54 ± 27.82 | <0.001 | 0.81 |

| Commercial Milk Formula Intake | Total Milk Intake 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable Models | Adjusted Models | Univariable Models | Adjusted Models | |||||||

| Parameters (n = 281) | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | Birth Weight p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | Birth Weight p-Value |

| Time postpartum (months) | 0.96 ± 7.56 1 | 0.90 | 0.52 ± 7.57 2 | 0.95 | 0.29 | 20.29 ± 9.74 1 | 0.038 | 22.23 ± 9.55 2 | 0.021 | <0.001 |

| Birth mode 5 | NA | 0.46 | NA | 0.46 | 0.32 | NA | 0.51 | NA | 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Infant factors | ||||||||||

| Infant birth gestation (weeks) | −7.88 ± 7.12 | 0.27 | NA | NA | NA | 9.51 ± 9.24 | 0.30 | NA | NA | NA |

| Infant birth weight (g) | −19.23 ± 17.86 | 0.28 | NA | NA | NA | 79.13 ± 22.62 | <0.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Infant sex (male) | 12.90 ± 15.47 | 0.41 | NA | NA | NA | 80.42 ± 19.46 | <0.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Maternal factors | ||||||||||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.89 ± 1.85 | 0.63 | 0.88 ± 1.85 | 0.64 | 0.28 | −1.11 ± 2.39 | 0.64 | −1.06 ± 2.34 | 0.65 | <0.001 |

| Education level | NA | 0.38 | NA | 0.38 | 0.33 | NA | 0.88 | NA | 0.87 | <0.001 |

| Parity | −23.79 ± 9.76 | 0.016 | −22.90 ± 9.83 | 0.021 | 0.41 | −12.33 ± 12.74 | 0.33 | −17.36 ± 12.54 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| Duration of previous lactations (months) | −1.73 ± 0.73 | 0.019 | −1.62 ± 0.76 | 0.034 | 0.56 | 0.24 ± 0.90 | 0.79 | −0.75 ± 0.91 | 0.41 | <0.001 |

| Breast volume (cm3) 6 | −0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.34 | −0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.62 | −0.03 ± 0.04 | 0.45 | −0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | −1.31 ± 1.13 | 0.25 | −1.10 ± 1.15 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 2.01 ± 1.46 | 0.17 | 0.96 ± 1.47 | 0.51 | 0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | −0.16 ± 0.52 | 0.75 | −0.08 ± 0.52 | 0.87 | 0.30 | −1.69 ± 0.66 | 0.011 | −2.06 ± 0.65 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.04 ± 1.61 | 0.98 | 0.17 ± 1.61 | 0.92 | 0.28 | −7.09 ± 2.03 | <0.001 | −7.64 ± 1.99 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | −2.03 ± 1.11 | 0.069 | −1.85 ± 1.14 | 0.11 | 0.51 | −1.78 ± 1.44 | 0.22 | −3.12 ± 1.44 | 0.032 | <0.001 |

| Fat-free mass index (kg/m2) | −5.45 ± 3.67 | 0.14 | −4.97 ± 3.71 | 0.18 | 0.39 | −10.53 ± 4.72 | 0.026 | −13.26 ± 4.65 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 0.67 ± 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.72 ± 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.26 | −3.19 ± 1.02 | 0.002 | −3.41 ± 1.00 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fat mass (%) | 2.25 ± 1.23 | 0.068 | 2.18 ± 1.23 | 0.078 | 0.33 | −4.94 ± 1.57 | 0.002 | −4.64 ± 1.54 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Fat mass index (kg/m2) | 2.37 ± 2.36 | 0.32 | 2.41 ± 2.36 | 0.31 | 0.28 | −11.00 ± 2.98 | <0.001 | −11.15 ± 2.92 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fat mass to fat-free mass ratio | 99.06 ± 46.96 | 0.036 | 96.41 ± 47.04 | 0.041 | 0.34 | −197.30 ± 59.99 | 0.001 | −185.61 ± 59.01 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| 24 h milk production parameters | ||||||||||

| 24 h milk production (g) | −0.28 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.28 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.62 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.049 |

| Breastfeeding frequency 7 | −8.45 ± 1.79 | <0.001 | −8.37 ± 1.79 | <0.001 | 0.40 | 0.38 ± 2.42 | 0.87 | −0.11 ± 2.38 | 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Expressing frequency 7 | 6.79 ± 2.19 | 0.002 | 6.60 ± 2.21 | 0.003 | 0.47 | 0.95 ± 2.92 | 0.75 | 2.21 ± 0.77 | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Milk removal frequency 7 | −4.42 ± 2.00 | 0.028 | −4.53 ± 2.00 | 0.025 | 0.24 | 1.20 ± 2.61 | 0.65 | 1.62 ± 2.56 | 0.53 | <0.001 |

| Mean breast storage capacity (g) 8 | −0.78 ± 0.13 | <0.001 | −0.77 ± 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 1.45 ± 0.20 | <0.001 | 1.37 ± 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.063 |

| Mean PAMR (%) 9 | −0.04 ± 0.63 | 0.95 | −0.004 ± 0.62 | 0.99 | 0.12 | 0.27 ± 0.95 | 0.77 | 0.17 ± 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.004 |

| Maternal expressing status | ||||||||||

| Expressing status | NA | <0.001 | NA | <0.001 | 0.57 | NA | 0.45 | NA | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| EP 10 vs. BF 11 | 147.83 ± 35.36 3 | <0.001 | 147.01 ± 35.43 | <0.001 | 0.57 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| OP 12 vs. BF 11 | −0.35 ± 17.15 | 1.00 | −0.44 ± 17.17 | 1.00 | 0.57 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| PP 13 vs. BF 11 | 117.67 ± 29.03 | <0.001 | 115.91 ± 29.23 | <0.001 | 0.57 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| OP 12 vs. EP 10 | −148.17 ± 37.02 | <0.001 | −147.45 ± 37.09 | <0.001 | 0.57 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| PP 13 vs. EP 10 | −30.16 ± 43.81 | 0.89 | −31.10 ± 43.89 | 0.89 | 0.57 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| PP 13 vs. OP 12 | 118.01 ± 31.04 | <0.001 | 116.35 ± 31.21 | 0.001 | 0.57 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mediation Effects | Standardised Regression Estimate (Standard Error) | p-Value | Fit Statistics 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | −0.19 (0.05) | <0.001 | CFI: | 0.98 |

| Direct | −0.06 (0.04) | 0.15 | TLI: | 0.95 |

| Indirect | −0.13 (0.04) | <0.001 | RMSEA: | 0.05 |

| %Mediated | 67.5% | SRMR: | 0.04 | |

References

- Geddes, D.T.; Gridneva, Z.; Perrella, S.L.; Mitoulas, L.R.; Kent, J.C.; Stinson, L.F.; Lai, C.T.; Sakalidis, V.; Twigger, A.J.; Hartmann, P.E. 25 years of research in human lactation: From discovery to translation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oken, E.; Fields, D.A.; Lovelady, C.A.; Redman, L.M. TOS Scientific Position Statement: Breastfeeding and Obesity. Obesity 2017, 25, 1864–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzorou, M.; Papandreou, D.; Vasios, G.K.; Pavlidou, E.; Antasouras, G.; Psara, E.; Taha, Z.; Poulios, E.; Giaginis, C. Exclusive breastfeeding for at least four months is associated with a lower prevalence of overweight and obesity in mothers and their children after 2–5 years from delivery. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, G.; Wang, P.P. The association between breastfeeding and childhood obesity: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuoyire, D.A.; Tampah-Naah, A.M. Association of breastfeeding duration with overweight and obesity among women in Ghana. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2024, 5, 1251849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nommsen-Rivers, L.A.; Wagner, E.A.; Roznowski, D.M.; Riddle, S.W.; Ward, L.P.; Thompson, A. Measures of maternal metabolic health as predictors of severely low milk production. Breastfeed. Med. 2022, 17, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, J.C.; Mitoulas, L.R.; Cregan, M.D.; Ramsay, D.T.; Doherty, D.A.; Hartmann, P.E. Volume and frequency of breastfeedings and fat content of breast milk throughout the day. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e387–e395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianni, M.L.; Bettinelli, M.E.; Manfra, P.; Sorrentino, G.; Bezze, E.; Plevani, L.; Cavallaro, G.; Raffaeli, G.; Crippa, B.L.; Colombo, L.; et al. Breastfeeding difficulties and risk for early breastfeeding cessation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, L. Maternal perceptions of insufficient milk supply in breastfeeding. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2008, 40, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galipeau, R.; Dumas, L.; Lepage, M. Perception of not having enough milk and actual milk production of first-time breastfeeding mothers: Is there a difference? Breastfeed. Med. 2017, 12, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Perrella, S.L.; Lai, C.T.; Taylor, N.L.; Geddes, D.T. Causes of low milk supply: The roles of estrogens, progesterone, and related external factors. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 15, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonfiglio, D.C.; Ramos-Lobo, A.M.; Freitas, V.M.; Zampieri, T.T.; Nagaishi, V.S.; Magalhães, M.; Cipolla-Neto, J.; Cella, N.; Donato, J., Jr. Obesity impairs lactation performance in mice by inducing prolactin resistance. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, J.A.; Rasmussen, K.M.; Kjolhede, C.L. Maternal obesity and breast-feeding success in a rural population of white women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 66, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesta-Castillejos, A.; Gomez-Salgado, J.; Rodriguez-Almagro, J.; Ortiz-Esquinas, I.; Hernandez-Martinez, A. Relationship between maternal body mass index with the onset of breastfeeding and its associated problems: An online survey. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2020, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepe, M.; Bacardi Gascon, M.; Castaneda-Gonzalez, L.M.; Perez Morales, M.E.; Jimenez Cruz, A. Effect of maternal obesity on lactation: Systematic review. Nutr. Hosp. 2011, 26, 1266–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, L.H.; Donath, S. A systematic review of maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2007, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi-Nazari, S.S.; Hasani, J.; Izadi, N.; Najafi, F.; Rahmani, J.; Naseri, P.; Rajabi, A.; Clark, C. The effect of pre-pregnancy body mass index on breastfeeding initiation, intention and duration: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, J.A.; Rasmussen, K.M.; Kjolhede, C.L. High prepregnant body mass index is associated with poor lactation outcomes among white, rural women independent of psychosocial and demographic correlates. J. Hum. Lact. 2004, 20, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bever Babendure, J.; Reifsnider, E.; Mendias, E.; Moramarco, M.W.; Davila, Y.R. Reduced breastfeeding rates among obese mothers: A review of contributing factors, clinical considerations and future directions. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, K.M.; Hilson, J.A.; Kjolhede, C.L. Obesity may impair lactogenesis II. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 3009S–3011S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.R.; de Castro, L.S.; Chang, Y.S.; Sañudo, A.; Marcacine, K.O.; Amir, L.; Ross, M.G.; Coca, K.P. Breastfeeding practices and problems among obese women compared with nonobese women in a Brazilian hospital. Women’s Health Rep. 2021, 2, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauff, L.E.; Leonard, S.A.; Rasmussen, K.M. Associations of maternal obesity and psychosocial factors with breastfeeding intention, initiation, and duration. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalrymple, K.V.; Briley, A.L.; Tydeman, F.A.S.; Seed, P.T.; Singh, C.M.; Flynn, A.C.; White, S.L.; Poston, L.; UPBEAT Consortium. Breastfeeding behaviours in women with obesity; associations with weight retention and the serum metabolome: A secondary analysis of UPBEAT. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 1472–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C. Commentary: The paradox of body mass index in obesity assessment: Not a good index of adiposity, but not a bad index of cardio-metabolic risk. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuebe, A. Associations among lactation, maternal carbohydrate metabolism, and cardiovascular health. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 58, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddulph, C.; Holmes, M.; Kuballa, A.; Carter, R.J.; Maher, J. Beyond the BMI: Validity and practicality of postpartum body composition assessment methods during lactation: A scoping review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, A.V.; Mildon, A.; Daniel, A.I.; Pitino, M.A.; Baxter, J.B.; Beggs, M.R.; Unger, S.L.; O’Connor, D.L.; Walton, K. Is maternal body weight or composition associated with onset of lactogenesis II, human milk production, or infant consumption of mother’s own milk? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lai, C.T.; Perrella, S.L.; McEachran, J.L.; Gridneva, Z.; Geddes, D.T. Maternal breast growth and body mass index are associated with low milk production in women. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridneva, Z.; Rea, A.; Weight, D.; McEachran, J.L.; Lai, C.T.; Perrella, S.L.; Geddes, D.T. Maternal factors, breast anatomy, and milk production during established lactation—An ultrasound investigation. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, D.T.; Sakalidis, V.S.; Hepworth, A.R.; McClellan, H.L.; Kent, J.C.; Lai, C.T.; Hartmann, P.E. Tongue movement and intra-oral vacuum of term infants during breastfeeding and feeding from an experimental teat that released milk under vacuum only. Early Hum. Dev. 2012, 88, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, C.D.; McKenzie, S.A.; Devine, C.M.; Thornburg, L.L.; Rasmussen, K.M. Obese women experience multiple challenges with breastfeeding that are either unique or exacerbated by their obesity: Discoveries from a longitudinal, qualitative study. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2017, 13, e12344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenberg Weisband, Y.; Keim, S.A.; Keder, L.M.; Geraghty, S.R.; Gallo, M.F. Early breast milk pumping intentions among postpartum women. Breastfeed. Med. 2017, 12, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.D.; Gay, M.C.L.; Wlodek, M.E.; Geddes, D.T. Breastfeeding a small for gestational age infant, complicated by maternal gestational diabetes: A case report. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwaydi, M.A.; Wlodek, M.E.; Lai, C.T.; Prosser, S.A.; Geddes, D.T.; Perrella, S.L. Delayed secretory activation and low milk production in women with gestational diabetes: A case series. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirakittidul, P.; Panichyawat, N.; Chotrungrote, B.; Mala, A. Prevalence and associated factors of breastfeeding in women with gestational diabetes in a University Hospital in Thailand. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2019, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, H.; Arden, M. Factors associated with breastfeeding up to 6 months postpartum in mothers with diabetes. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2009, 38, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Quijano, M.E.; Pérez-Nieves, V.; Sámano, R.; Chico-Barba, G. Gestational diabetes mellitus, breastfeeding, and progression to type 2 diabetes: Why is it so hard to achieve the protective benefits of breastfeeding? A narrative review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calculating Cup Volume and Breast Weight. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bra_size#cite_note-Plussize_Chart-103 (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Kent, J.; Mitoulas, L.; Cox, D.B.; Owens, R.; Hartmann, P. Breast volume and milk production during extended lactation in women. Exp. Physiol. 1999, 84, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridneva, Z.; Rea, A.; Hepworth, A.R.; Ward, L.C.; Lai, C.T.; Hartmann, P.E.; Geddes, D.T. Relationships between breastfeeding patterns and maternal and infant body composition over the first 12 months of lactation. Nutrients 2018, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.C.; Isenring, E.; Dyer, J.M.; Kagawa, M.; Essex, T. Resistivity coefficients for body composition analysis using bioimpedance spectroscopy: Effects of body dominance and mixture theory algorithm. Physiol. Meas. 2015, 36, 1529–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridneva, Z.; Hepworth, A.; Ward, L.; Lai, C.T.; Hartmann, P.; Geddes, D.T. Bioimpedance spectroscopy in the infant: Effect of milk intake and extracellular fluid reservoirs on resistance measurements in term breastfed infants. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanItallie, T.B.; Yang, M.U.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Funk, R.C.; Boileau, R.A. Height-normalized indices of the body’s fat-free mass and fat mass: Potentially useful indicators of nutritional status. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 52, 953–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.; Hepworth, A.; Sherriff, J.; Cox, D.; Mitoulas, L.; Hartmann, P. Longitudinal changes in breastfeeding patterns from 1 to 6 months of lactation. Breastfeed. Med. 2013, 8, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, M.C.; Keller, R.; Seacat, J.; Lutes, V.; Neifert, M.; Casey, C.; Allen, J.; Archer, P. Studies in human lactation: Milk volumes in lactating women during the onset of lactation and full lactation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1988, 48, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.C.; Mitoulas, L.R.; Cregan, M.D.; Geddes, D.T.; Larsson, M.; Doherty, D.A.; Hartmann, P.E. Importance of vacuum for breastmilk expression. Breastfeed. Med. 2008, 3, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, W.J.; Kent, J.C.; Lai, C.T.; Rea, A.; Hepworth, A.R.; Murray, K.; Geddes, D.T. Reproducibility of the creamatocrit technique for the measurement of fat content in human milk. Food Chem. 2021, 356, 129708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, S.E.J.; Di Rosso, A.; Owens, R.A.; Hartmann, P.E. Degree of breast emptying explains changes in the fat content, but not fatty acid composition, of human milk. Exp. Physiol. 1993, 78, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.C.; Ramsay, D.T.; Doherty, D.; Larsson, M.; Hartmann, P.E. Response of breasts to different stimulation patterns of an electric breast pump. J. Hum. Lact. 2003, 19, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausell, R.B.; Li, Y.-F. Power Analysis for Experimental Research; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 363. [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidian, M.; Mata, M. 2—Advances in Analysis of Mean and Covariance Structure when Data are Incomplete. In Handbook of Computing and Statistics with Applications; Lee, S.-Y., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, D.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Heo, M.; Jebb, S.A.; Murgatroyd, P.R.; Sakamoto, Y. Healthy percentage body fat ranges: An approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girchenko, P.; Lahti-Pulkkinen, M.; Hämäläinen, E.; Laivuori, H.; Villa, P.; Kajantie, E.; Räikkönen, K. Associations of polymetabolic risk of high maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index with pregnancy complications, birth outcomes, and early childhood neurodevelopment: Findings from two pregnancy cohorts. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuebe, A. The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 2, 222–231. [Google Scholar]

- Munblit, D.; Crawley, H.; Hyde, R.; Boyle, R.J. Health and nutrition claims for infant formula are poorly substantiated and potentially harmful. BMJ 2020, 369, m875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.; Hauck, Y.; Mabbott, K.; Officer, K.; Ashton, L.; Bradfield, Z. Influencers of women’s choice and experience of exclusive formula feeding in hospital. Midwifery 2021, 103, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, D.T.; Kent, J.C.; Hartmann, R.A.; Hartmann, P.E. Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. J. Anat. 2005, 206, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.E.; Owens, R.A.; Cox, D.B.; Kent, J.C. Breast development and control of milk synthesis. Food Nutr. Bull. 1996, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roznowski, D.M.; Wagner, E.A.; Riddle, S.W.; Nommsen-Rivers, L.A. Validity of a 3-hour breast milk expression protocol in estimating current maternal milk production capacity and infant breast milk intake in exclusively breastfeeding dyads. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kelleher, S.L. Biological underpinnings of breastfeeding challenges: The role of genetics, diet, and environment on lactation physiology. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 311, E405–E422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holowko, N.; Jones, M.; Koupil, I.; Tooth, L.; Mishra, G. High education and increased parity are associated with breast-feeding initiation and duration among Australian women. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2551–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Breastfeeding; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Khanal, V. Influence of breastfeeding education and support on predominant breastfeeding: Findings from a community-based prospective cohort study in Western Nepal. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, K.E.; Braveman, P.; Cubbin, C.; Chavez, G.F.; Kiely, J.L. Socioeconomic status and breastfeeding initiation among California mothers. Public Health Rep. 2006, 121, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, P.A.R.; Barros, A.J.D.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Vaz, J.S.; Baker, P.; Lutter, C.K. Maternal education and equity in breastfeeding: Trends and patterns in 81 low- and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2019. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, D.B.; Roberts, K.J.; Grosskopf, N.A.; Basch, C.H. An evaluation of the effectiveness of school-based breastfeeding education. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singletary, N.; Chetwynd, E.; Goodell, L.S.; Fogleman, A. Stakeholder views of breastfeeding education in schools: A systematic mixed studies review of the literature. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2017, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridneva, Z.; Warden, A.H.; McEachran, J.L.; Perrella, S.L.; Lai, C.T.; Geddes, D.T. Maternal and infant characteristics and pumping profiles of women that predominantly pump milk for their infants. Nutrients 2025, 17, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.A.; Labiner-Wolfe, J.; Geraghty, S.R.; Rasmussen, K.M. Associations between high prepregnancy body mass index, breast-milk expression, and breast-milk production and feeding. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, A.H.; Sakalidis, V.S.; McEachran, J.L.; Lai, C.T.; Perrella, S.L.; Geddes, D.T.; Gridneva, Z. Consecutive lactation, infant birth weight and sex do not associate with milk production and infant milk intake in breastfeeding women. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, M.; Robertson, S.; Merkatz, R.; Klaus, M. Milk intake and frequency of feeding in breast-fed infants. Early Hum. Dev. 1982, 7, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrom, J.L.; Meier, P.P.; Jegier, B.; Motykowski, J.E.; Zuleger, J.L. Comparison of milk output from the right and left breasts during simultaneous pumping in mothers of very low birthweight infants. Breastfeed. Med. 2007, 2, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olga, L.; Vervoort, J.; van Diepen, J.A.; Gross, G.; Petry, C.J.; Prentice, P.M.; Chichlowski, M.; van Tol, E.A.F.; Hughes, I.A.; Dunger, D.B.; et al. Associations between breast milk intake volume, macronutrient intake and infant growth in a longitudinal birth cohort: The Cambridge Baby Growth and Breastfeeding Study (CBGS-BF). Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 130, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, T.H.; Haisma, H.; Wells, J.C.; Mander, A.P.; Whitehead, R.G.; Bluck, L.J. How much human milk do infants consume? Data from 12 countries using a standardized stable isotope methodology. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 2227–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.C.; Gardner, H.; Geddes, D.T. Breastmilk production in the first 4 weeks after birth of term infants. Nutrients 2016, 8, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, M.; Robertson, S.; Friedman, A.; Klaus, M. Effect of frequent breast-feeding on early milk production and infant weight gain. Pediatrics 1983, 72, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.C.; Prime, D.K.; Garbin, C.P. Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 41, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabek, A.; Li, C.; Du, C.; Nan, L.; Ni, J.; Elgazzar, E.; Ma, Y.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Zhang, S. Effects of parity and days in milk on milk composition in correlation with β-hydroxybutyrate in tropic dairy cows. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, K.; Power, M.L.; Oftedal, O.T. Rhesus macaque milk: Magnitude, sources, and consequences of individual variation over lactation. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2009, 138, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, C.O.; Dolzhenko, E.; Hodges, E.; Smith, A.D.; Hannon, G.J. An epigenetic memory of pregnancy in the mouse mammary gland. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.C.; Ashton, E.; Hardwick, C.M.; Rea, A.; Murray, K.; Geddes, D.T. Causes of perception of insufficient milk supply in Western Australian mothers. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2021, 17, e13080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.C.; Woolridge, M.W.; Greenwood, R.J.; McGrath, L. Maternal predictors of early breast milk output. Acta Paediatr. 1999, 88, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Woolridge, M.; Greenwood, R. Breastfeeding: It is worth trying with the second baby. Lancet 2001, 358, 986–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butte, N.F.; Garza, C.; Stuff, J.E.; Smith, E.O.; Nichols, B.L. Effect of maternal diet and body composition on lactational performance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984, 39, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, K.G.; Lönnerdal, B. Infant self-regulation of breast milk intake. Acta Paediatr. 1986, 75, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattigan, S.; Ghisalberti, A.V.; Hartmann, P.E. Breast-milk production in Australian women. Br. J. Nutr. 1981, 45, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialich, M.S.; Sicchieri, J.M.F.; Jordao, A.A., Jr. Analysis of body composition: A critical review of the use of bioelectrical impedance analysis. Int. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, K.S.; Alexander, M.P.; Serdula, M.K.; Davis, M.K.; Bowman, B.A. Assessment of infant feeding: The validity of measuring milk intake. Nutr. Rev. 2002, 60, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Mean ± SD or n (%) and Min–Max |

|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | n = 281 |

| Age (years) | 32.7 ± 4.2 (23–44) 1 |

| Parity (primiparous) | 155 (55.2) (1–4) |

| Highest education level | n = 281 |

| High school | 17 (6.0) |

| Certificate/apprenticeship | 71 (25.3) |

| Tertiary degree | 193 (68.7) |

| Race | n = 278 |

| Australian | 251 (90.3) |

| Asian | 21 (7.6) |

| Other | 6 (2.1) |

| Infant characteristics | n = 281 |

| Sex (Male) | 139 (49.5) |

| Birth gestation (weeks) | 39.5 ± 1.1 (37.0–43.0) |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.498 ± 433 (2.540–5.045) |

| Birth mode | n = 278 |

| Spontaneous vaginal | 138 (49.6) |

| Assisted vaginal | 38 (13.7) |

| Elective caesarean | 60 (21.6) |

| Non-elective caesarean | 42 (15.1) |

| Maternal Characteristics (n = 281) | Mean ± SD or n (%) | Min–Max |

|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 73.6 ± 15.1 1 | 42.6–122.0 2 |

| Height (cm) | 166.4 ± 6.9 | 143.0–185.0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (n = 281) | ||

| Overall | 26.5 ± 4.8 | 17.3–41.9 |

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 7 (2.5) | 17.3–18.4 |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 114 (40.6) | 18.8–24.9 |

| 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 95 (33.8) | 25.0–29.9 |

| >30 kg/m2 | 65 (23.1) | 30.0–41.9 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 45.3 ± 6.9 | 29.9–74.8 |

| Fat-free mass index (kg/m2) | 16.3 ± 2.1 | 11.6–24.0 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 28.3 ± 9.6 | 10.2–58.4 |

| Fat mass index (kg/m2) | 10.2 ± 3.3 | 3.7–19.8 |

| Fat mass (%) (n = 281) | ||

| Overall | 37.6 ± 6.3 | 19.2–53.3 |

| <21.0% | 2 (0.7) | 19.2–20.4 |

| 21.0–32.9% | 64 (22.8) | 23.2–32.8 |

| 33.0–38.9% | 94 (33.5) | 33.0–38.9 |

| >39% | 121 (43.1) | 39.0–53.4 |

| Fat mass to fat-free mass ratio | 0.56 ± 0.17 | 0.24–1.14 |

| Breast volume (cm3) 3 | 780.8 ± 304.0 | 180–1580 |

| Parameters (n = 281) | Mean ± SD | Min–Max |

|---|---|---|

| Total 24 h milk production (g) | 778 ± 238 1 | 67–1739 2 |

| Milk removal frequency (per breast) | 12.3 ± 3.8 | 4–25 |

| Breastfeeding frequency (per breast) | 10.3 ± 4.2 | 0–22 |

| Milk intake from the breast (g) | 672 ± 280 | 0–1344 |

| Expressing frequency (per breast) | 2.0 ± 3.5 | 0–16 |

| Pumping session frequency | 1.2 ± 2.1 | 0–11 |

| Breast milk expressed (g) | 131 ± 282 | 0–1870 |

| Expressed breast milk intake (g) 3 | 86 ± 198 | 0–1200 |

| Intake of breast milk (g) 3,4 | 763 ± 208 | 0–1344 |

| Commercial milk formula intake (g) 5 | 42 ± 129 | 0–775 |

| Total milk intake (g) 3,6 | 805 ± 167 | 348–1344 |

| Mean breast storage capacity (g) 7 | 160.8 ± 55.3 | 36.3–354.9 |

| Pooled mean PAMR (%) 8 | 74.3 ± 12.8 | 34.9–125.9 |

| Parameters | Mean ± SD | Min–Max |

|---|---|---|

| All mothers | n = 281 | |

| 24 h milk production (g) | 778 ± 238 1 | 67–1739 2 |

| 24 h milk breastfed (g) | 672 ± 280 | 0–1344 |

| 24 h milk expressed (g) | 131 ± 282 | 0–1870 |

| Left breast storage capacity (g) 3 | 159.7 ± 64.3 | 24.0–404.1 |

| Right breast storage capacity (g) 3 | 162.3 ± 70.4 | 32.5–416.6 |

| Mean breast storage capacity (g) 4 | 160.8 ± 55.3 | 36.3–354.9 |

| Left breast mean PAMR (%) 5 | 74.1 ± 16.6 | 39.1–167.4 |

| Right breast mean PAMR (%) 4 | 74.9 ± 17.9 | 25.2–190.6 |

| Pooled mean PAMR (%) 6 | 74.3 ± 12.8 | 34.9–125.9 |

| Breastfeeding only mothers | n = 174 | |

| 24 h milk production (g) | 744 ± 181 | 238–1236 |

| 24 h milk breastfed (g) | 775 ± 188 | 230–1344 |

| 24 h milk expressed (g) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | NA |

| Left breast mean PAMR (%) 7 | 75.6 ± 17.5 | 39.1–167.4 |

| Right breast mean PAMR (%) 8 | 76.9 ± 19.2 | 25.2–190.6 |

| Pooled mean PAMR (%) 7 | 75.8 ± 13.2 | 34.9–125.9 |

| Occasionally pumping mothers | n = 73 | |

| 24 h milk production (g) | 818 ± 223 | 324–1331 |

| 24 h milk breastfed (g) | 675 ± 215 | 266–1156 |

| 24 h milk expressed (g) | 167 ± 94 | 15–448 |

| Left breast mean PAMR (%) 9 | 69.4 ± 12.2 | 44.2–99.2 |

| Right breast mean PAMR (%) 10 | 69.9 ± 16.2 | 26.8–135.3 |

| Pooled mean PAMR (%) 9 | 70.0 ± 10.9 | 41.3–104.9 |

| Predominantly pumping mothers | n = 20 | |

| 24 h milk production (g) | 772 ± 406 | 67–1540 |

| 24 h milk breastfed (g) | 236 ± 166 | 18–538 |

| 24 h milk expressed (g) | 539 ± 284 | 48–1060 |

| Left breast mean PAMR (%) 11 | 70.5 ± 18.2 | 47.5–118.9 |

| Right breast mean PAMR (%) 12 | 72.6 ± 13.9 | 48.3–93.9 |

| Pooled mean PAMR (%) 12 | 72.0 ± 13.7 | 51.0–96.6 |

| Exclusively pumping mothers | n = 14 | |

| 24 h milk production (g) | 993 ± 444 | 158–1739 |

| 24 h milk breastfed (g) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | NA |

| 24 h milk expressed (g) | 991 ± 502 | 173–1870 |

| Left breast mean PAMR (%) 13 | 82.2 ± 11.4 | 62.2–99.2 |

| Right breast mean PAMR (%) 13 | 83.9 ± 8.1 | 72.5–95.6 |

| Pooled mean PAMR (%) 13 | 83.0 ± 8.4 | 69.2–91.8 |

| Predictors (n = 281) | Univariable Models | Adjusted Models | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | Birth Weight p-Value | |

| Time postpartum (months) | 19.58 ± 13.82 1 | 0.16 | 22.09 ± 13.62 2 | 0.11 | 0.001 |

| Birth mode 4 | NA | 0.37 | NA | 0.35 | 0.001 |

| Infant factors | |||||

| Infant birth gestation (weeks) | 22.67 ± 13.03 | 0.083 | NA | NA | NA |

| Infant birth weight (g) | 101.42 ± 32.26 | 0.002 | NA | NA | NA |

| Infant sex (male) | 77.54 ± 28.03 | 0.006 | NA | NA | NA |

| Maternal factors | |||||

| Maternal age (years) | −3.40 ± 3.39 | 0.32 | 2.0 ± 3.5 | 0.32 | 0.002 |

| Education level | NA | 0.64 | NA | 0.63 | 0.002 |

| Parity | −10.16 ± 18.09 | 0.58 | −16.33 ± 17.90 | 0.36 | 0.001 |

| Duration of previous lactations (months) | 1.49 ± 1.32 | 0.26 | 0.43 ± 1.34 | 0.75 | 0.003 |

| Breast volume (cm3) 5 | 0.03 ± 0.05 | 0.62 | 0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.77 | 0.007 |

| Height (cm) | 2.05 ± 2.07 | 0.32 | 0.71 ± 2.09 | 0.73 | 0.003 |

| Weight (kg) | −2.05 ± 0.94 | 0.030 | −2.51 ± 0.93 | 0.007 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −7.97 ± 2.91 | 0.007 | −8.69 ± 2.87 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | −1.19 ± 2.05 | 0.56 | −2.83 ± 2.07 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| Fat-free mass index (kg/m2) | −7.86 ± 6.75 | 0.25 | −11.25 ± 6.70 | 0.095 | <0.001 |

| Fat mass (kg) | −4.37 ± 1.45 | 0.003 | −4.65 ± 1.43 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fat mass (%) | −7.06 ± 2.23 | 0.002 | −6.68 ± 2.20 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Fat mass index (kg/m2) | −14.05 ± 4.26 | 0.001 | −14.26 ± 4.2 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Fat mass to fat-free mass ratio | −290.63 ± 85.18 | <0.001 | −275.96 ± 84.13 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| 24 h milk production parameters | |||||

| Breast milk fed (g) 6,7 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.88 |

| Expressed breast milk fed (g) 6 | 0.33 ± 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Commercial milk formula fed (g) 8 | −0.91 ± 0.09 | <0.001 | −0.90 ± 0.09 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Total milk fed (g) 6,9 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.92 ± 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.33 |

| Breastfeeding frequency (each breast) | −0.80 ± 3.37 | 0.81 | −1.31 ± 3.32 | 0.69 | 0.002 |

| Expressing frequency (each breast) | 15.93 ± 3.94 | <0.001 | 17.53 ± 3.87 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Milk removal frequency (each breast) | 12.41 ± 3.63 | <0.001 | 12.98 ± 31.61 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mean breast storage capacity (g) 10 | 2.67 ± 0.24 | <0.001 | 2.59 ± 0.24 | <0.001 | 0.12 |

| Pooled mean PAMR (%) 11 | 0.51 ± 1.33 | 0.70 | 0.34 ± 1.30 | 0.79 | 0.003 |

| Expressing status | |||||

| Expressing status | NA | <0.001 | NA | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| EP 12 vs. BF 13 | 248.90 ± 64.33 3 | <0.001 | 254.47 ± 63.19 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| OP 14 vs. BF 13 | 73.68 ± 32.29 | 0.096 | 74.71 ± 31.71 | 0.080 | <0.001 |

| PP 15 vs. BF 13 | 28.26 ± 54.67 | 0.95 | 47.39 ± 53.99 | 0.80 | <0.001 |

| OP 14 vs. EP 12 | −175.22 ± 67.56 | 0.044 | −179.76 ± 66.36 | 0.033 | <0.001 |

| PP 15 vs. EP 12 | −220.64 ± 80.69 | 0.030 | −207.08 ± 79.34 | 0.042 | <0.001 |

| PP 15 vs. OP 14 | −45.42 ± 58.44 | 0.86 | −27.31 ± 57.64 | 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Predictors (n = 281) | 24 h Breastfeeding Frequency | 24 h Expressing Frequency | 24 h Milk Removal Frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | |

| Time postpartum (months) | −0.60 ± 0.24 1 | 0.015 | −0.13 ± 0.21 | 0.51 | −0.73 ± 0.22 | 0.001 |

| Birth mode 3 | NA | 0.63 | NA | 0.064 | NA | 0.48 |

| Infant factors | ||||||

| Infant birth gestation (weeks) | 0.03 ± 0.23 | 0.90 | −0.08 ± 0.19 | 0.67 | −0.05 ± 0.21 | 0.80 |

| Infant birth weight (g) | 0.47 ± 0.58 | 0.42 | −0.90 ± 0.48 | 0.064 | −0.42 ± 0.53 | 0.43 |

| Infant sex (male) | −0.30 ± 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.46 ± 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.16 ± 0.46 | 0.72 |

| Maternal factors | ||||||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.05 ± 0.06 | 0.42 | −0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.64 | 0.03 ± 0.06 | 0.65 |

| Education level | NA | 0.70 | NA | 0.081 | *** | 0.012 |

| Parity | 0.18 ± 0.32 | 0.59 | −1.09 ± 0.26 | <0.001 | −0.91 ± 0.29 | 0.002 |

| Duration of previous lactations (months) | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.30 | −0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.004 | −0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.13 |

| Breast volume (cm3) 4 | −0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.073 | −0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.19 |

| Height (cm) | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.004 | −0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.059 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Weight (kg) | −0.0002 ± 0.02 | 0.99 | −0.004 ± 0.01 | 0.78 | −0.004 ± 0.02 | 0.79 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 0.68 | −0.04 ± 0.05 | 0.37 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 0.39 | −0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.047 | −0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.39 |

| Fat-free mass index (kg/m2) | −0.08 ± 0.12 | 0.50 | −0.12 ± 0.10 | 0.23 | −0.20 ± 0.11 | 0.063 |

| Fat mass (kg) | −0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.53 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.81 |

| Fat mass (%) | −0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.030 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 0.37 |

| Fat mass index (kg/m2) | −0.10 ± 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 0.16 | −0.01 ± 0.07 | 0.93 |

| Fat mass to fat-free mass ratio | −1.76 ± 1.54 | 0.25 | 2.94 ± 1.27 | 0.022 | 1.18 ± 1.40 | 0.40 |

| 24 h milk production parameters | ||||||

| 24 h milk production (g) | −0.0003 ± 0.001 | 0.81 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Breastfeeding frequency 5 | NA | NA | −0.43 ± 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Expressing frequency 5 | −0.63 ± 0.06 | <0.001 | NA | NA | 0.38 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Milk removal frequency 5 | 0.69 ± 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | <0.001 | NA | NA |

| Mean breast storage capacity (g) 6 | −0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.037 | −0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.20 | −0.02 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Pooled mean PAMR (%) 7 | −0.12 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | −0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.57 | −0.13 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Expressing status | ||||||

| Expressing status | NA | <0.001 | NA | <0.001 | NA | <0.001 |

| EP 8 vs. BF 9 | −11.21 ± 0.88 2 | <0.001 | 11.29 ± 0.43 | <0.001 | 0.08 ± 0.97 | 1.00 |

| OP 10 vs. BF 9 | 0.40 ± 0.44 | 0.79 | 3.22 ± 0.21 | <0.001 | 3.62 ± 0.49 | <0.001 |

| PP 11 vs. BF 9 | −5.81 ± 0.74 | <0.001 | 8.30 ± 0.36 | <0.001 | 2.49 ± 0.83 | 0.013 |

| OP 10 vs. EP 8 | 11.60 ± 0.92 | <0.001 | −8.07 ± 0.45 | <0.001 | 3.54 ± 1.02 | 0.003 |

| PP 11 vs. EP 8 | 5.40 ± 1.10 | <0.001 | −2.99 ± 0.53 | <0.001 | 2.41 ± 1.22 | 0.18 |

| PP 11 vs. OP 10 | −6.20 ± 0.80 | <0.001 | 5.08 ± 0.39 | <0.001 | −1.12 ± 0.88 | 0.56 |

| Predictors (n = 281) | Univariable Models | Adjusted Models | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | PE ± SE | Predictor p-Value | Birth Weight p-Value | |

| Time postpartum (months) | 2.15 ± 3.60 1 | 0.55 | 2.84 ± 3.53 2 | 0.42 | 0.003 |

| Birth mode 4 | NA | 0.54 | NA | 0.52 | 0.005 |

| Infant factors | |||||

| Infant birth gestation (weeks) | 3.28 ± 3.73 | 0.38 | −0.55 ± 3.91 | 0.89 | 0.006 |

| Infant birth weight (g) | 27.41 ± 9.30 | 0.004 | NA | NA | NA |

| Infant sex (male) | 21.03 ± 7.71 | 0.007 | 17.33 ± 7.76 | 0.027 | 0.013 |

| Maternal factors | |||||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.05 ± 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.10 ± 091 | 0.92 | 0.004 |

| Education level | NA | 0.95 | NA | 0.95 | 0.004 |

| Parity | 0.56 ± 5.04 | 0.91 | −1.61 ± 5.00 | 0.75 | 0.004 |

| Duration of previous lactations (months) | 0.39 ± 0.34 | 0.25 | −0.03 ± 0.35 | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| Breast volume (cm3) 5 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.061 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.096 | 0.032 |

| Height (cm) | 1.01 ± 0.56 | 0.076 | 0.63 ± 0.58 | 0.28 | 0.011 |

| Weight (kg) | −0.07 ± 0.26 | 0.79 | −0.24 ± 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.003 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.79 ± 0.82 | 0.34 | −1.09 ± 0.81 | 0.18 | 0.002 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 0.99 ± 0.55 | 0.071 | 0.59 ± 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.012 |

| Fat-free mass index (kg/m2) | 2.10 ± 1.80 | 0.24 | 1.20 ± 1.80 | 0.51 | 0.006 |

| Fat mass (kg) | −0.75 ± 0.41 | 0.072 | −0.90 ± 0.41 | 0.028 | 0.002 |

| Fat mass (%) | −1.93 ± 0.62 | 0.002 | −1.92 ± 0.61 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| Fat mass index (kg/m2) | −2.74 ± 1.21 | 0.025 | −2.97 ± 1.19 | 0.013 | 0.002 |

| Fat mass to fat-free mass ratio | −79.21 ± 23.64 | <0.001 | −78.12 ± 23.18 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| 24 h milk production parameters | |||||

| Breast milk fed (g) 6,7 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.38 |

| Expressed breast milk fed (g) 6 | −0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.72 | −0.004 ± 0.02 | 0.82 | 0.006 |

| Commercial milk formula fed (g) 8 | −0.19 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.18 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.018 |

| Total milk fed (g) 6,9 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.10 |

| Breastfeeding frequency (each breast) | −1.91 ± 0.91 | 0.037 | −2.05 ± 0.89 | 0.023 | 0.002 |

| Expressing frequency (each breast) | −1.36 ± 1.05 | 0.20 | −0.96 ± 1.04 | 0.36 | 0.006 |

| Milk removal frequency (each breast) | −3.64 ± 0.99 | <0.001 | −3.44 ± 0.98 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| Pooled mean PAMR (%) | −0.36 ± 0.31 | 0.24 | −0.40 ± 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.003 |

| Expressing status 10 | NA | 0.89 3 | NA | 0.98 | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gridneva, Z.; Warden, A.H.; Jin, X.; McEachran, J.L.; Lai, C.T.; Perrella, S.L.; Geddes, D.T. Maternal Adiposity, Milk Production and Removal, and Infant Milk Intake During Established Lactation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3726. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233726

Gridneva Z, Warden AH, Jin X, McEachran JL, Lai CT, Perrella SL, Geddes DT. Maternal Adiposity, Milk Production and Removal, and Infant Milk Intake During Established Lactation. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3726. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233726

Chicago/Turabian StyleGridneva, Zoya, Ashleigh H. Warden, Xuehua Jin, Jacki L. McEachran, Ching Tat Lai, Sharon L. Perrella, and Donna T. Geddes. 2025. "Maternal Adiposity, Milk Production and Removal, and Infant Milk Intake During Established Lactation" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3726. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233726

APA StyleGridneva, Z., Warden, A. H., Jin, X., McEachran, J. L., Lai, C. T., Perrella, S. L., & Geddes, D. T. (2025). Maternal Adiposity, Milk Production and Removal, and Infant Milk Intake During Established Lactation. Nutrients, 17(23), 3726. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233726