Anthocyanins Modulation of Gut Microbiota to Reverse Obesity-Driven Inflammation and Insulin Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

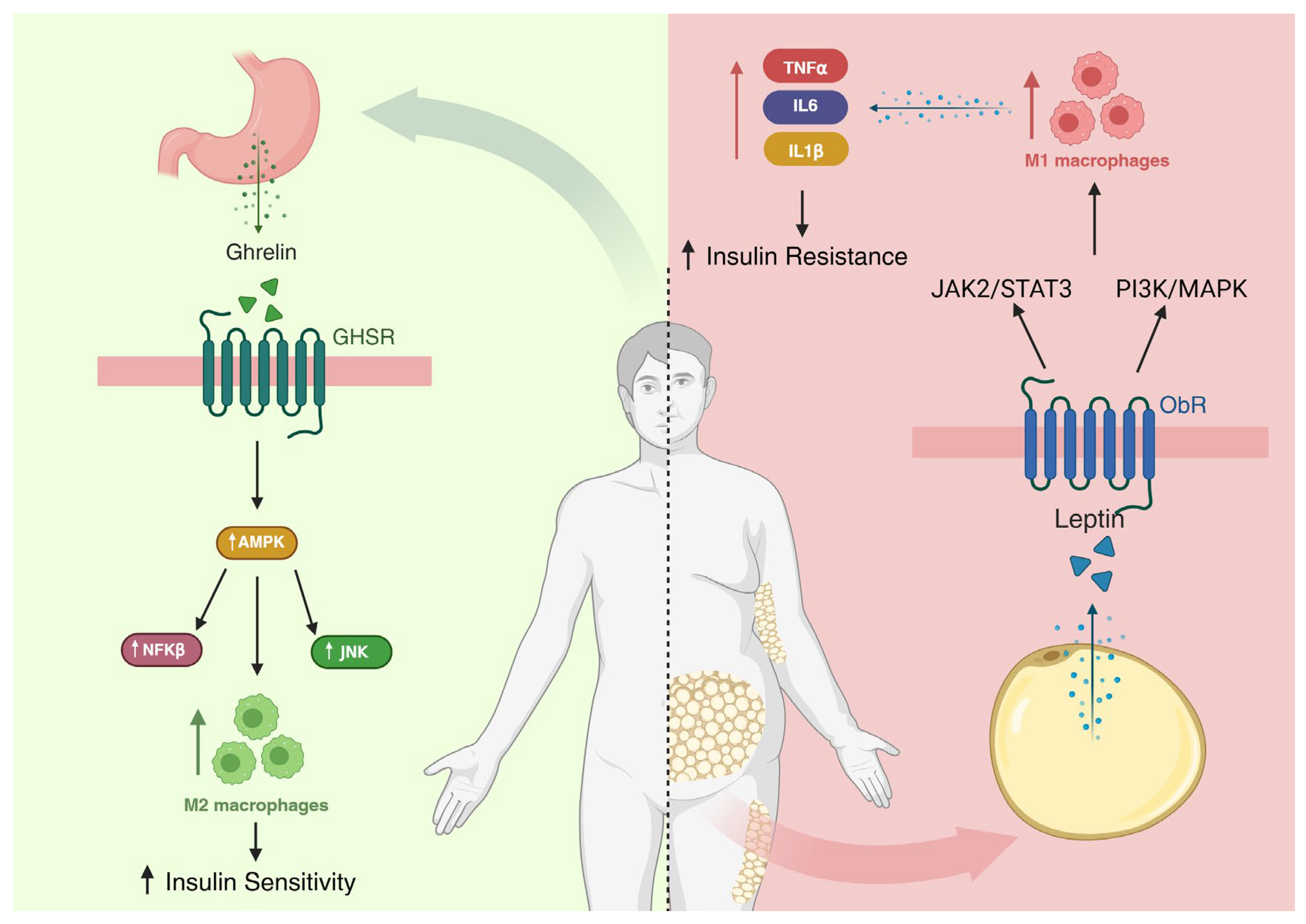

2. Energy Homeostasis and Neuroendocrine Regulation

3. Inflammation-Driven Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance in Obesity

4. Cardiometabolic and Hepatic Consequences of Insulin Resistance

5. Intestinal Barrier Integrity, Microbiota Shifts, and Their Role in Obesity-Related Inflammation

6. Bioactive Phytochemicals and Microbiota-Targeted Interventions: Dual Strategies Against Obesity-Associated Inflammation

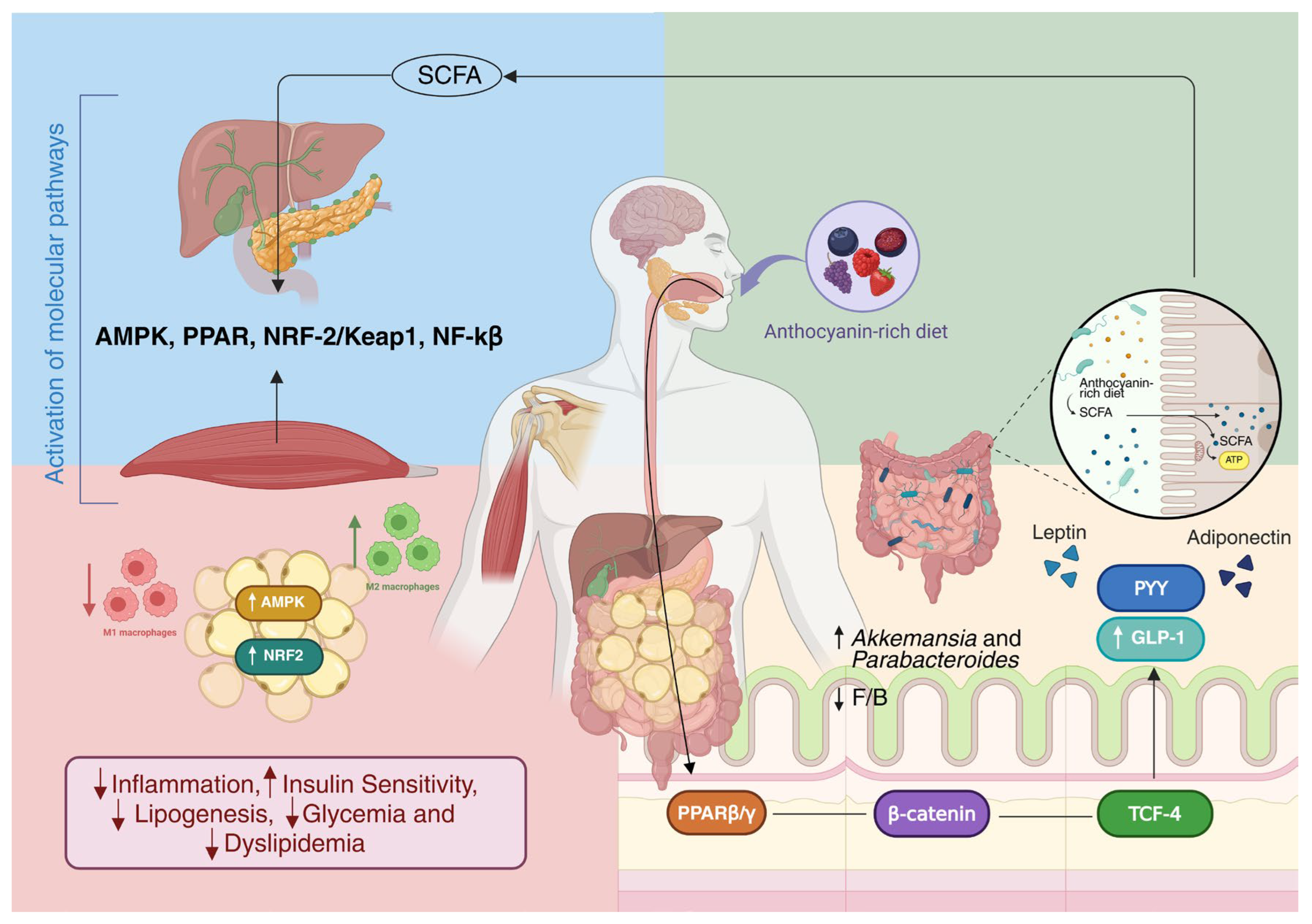

7. Anthocyanins: Chemical Characteristics, Bioavailability, Biological Effects, and Clinical Potential

8. Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Anthocyanins and Their Potential Synergistic Effects with Semaglutide and Tirzepatide

9. Anthocyanins: In Vitro, In Vivo and Clinical Evidence

| Anthocyanins | Food Source | Main Metabolic Effects | Molecular Mechanisms | Evidence (In vitro/In vivo/Human) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G) | Blueberry, Blackcurrant | ↑ GLP-1, ↑ Insulin, ↓ Lipotoxicity | PPARβ/δ–β-catenin–TCF-4, ER stress attenuation | In vitro [280,314,317] In vivo [282,289] Human [281,284] |

| Delphinidin | Blackcurrant, Elderberry | ↓ Inflammation, ↑ Antioxidant status | NF-κB inhibition, Nrf2 activation | In vitro [283,303,304,305] In vivo [283,288,302] Human [306] |

| Malvidin | Blueberry, Grape | ↓ Lipogenesis, ↓ Cholesterol | AMPK activation, PPARα/γ modulation | In vitro [301] In vivo [293,294,301] Human [292] |

| Pelargonidin | Strawberry, Raspberry | ↓ Postprandial glycaemia, ↓ LDL | NF-κB, LXR modulation | In vitro [296,297] In vivo [290,291,296,297,298] Human [254] |

| Petunidin | Blueberry, Purple star apple | ↑ Fat acid oxidation, ↓ TG | AMPK/Nrf2, SREBP-1c inhibition | In vitro [299,301] In vivo [300,301] Human [285,286] |

10. Anthocyanins, Microbiota and Gut–Liver Interactions

11. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Shafiee, A.; Nakhaee, Z.; Bahri, R.A.; Amini, M.J.; Salehi, A.; Jafarabady, K.; Seighali, N.; Rashidian, P.; Fathi, H.; Esmaeilpur Abianeh, F.; et al. Global prevalence of obesity and overweight among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, C.; Xiong, J.; Zhu, R.; Hong, Z.; He, Y. The global burden of high BMI among adolescents between 1990 and 2021. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Mohammed, R.A. Obesity: Prevalence, causes, consequences, management, preventive strategies and future research directions. Metab. Open 2025, 27, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCDRF. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliaki, C.; Dalamaga, M.; Liatis, S. Update on the Obesity Epidemic: After the Sudden Rise, Is the Upward Trajectory Beginning to Flatten? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Rodrigues, A.M.; Padez, C.; Rodrigues, D.; Dos Santos, E.A.; Baptista, L.C.; Liz Martins, M.; Fernandes, H.M. Ultra-processed food consumption and its association with risk of obesity, sedentary behaviors, and well-being in adolescents. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Quesada, R.; Monge-Rojas, R.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, S.; Araneda-Flores, J.; Cacau, L.T.; Cediel, G.; Gaitán-Charry, D.; Pizarro Quevedo, T.; Pinheiro Fernandes, A.C.; Rovirosa, A.; et al. Adherence to the EAT-Lancet Diet Among Urban and Rural Latin American Adolescents: Associations with Micronutrient Intake and Ultra-Processed Food Consumption. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.O.; Akinnusi, E.; Ottu, P.O.; Bridget, K.; Oyubu, G.; Ajiboye, S.A.; Waheed, S.A.; Collette, A.C.; Adebimpe, H.O.; Nwokafor, C.V.; et al. The impact of ultra-processed foods on cardiovascular diseases and cancer: Epidemiological and mechanistic insights. Asp. Mol. Med. 2025, 5, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Imran, L.; Banatwala, U.E.S.S. Unleashing the power of retatrutide: A possible triumph over obesity and overweight: A correspondence. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, S.; Rizza, S.; Federici, M. Microbiota-gut-brain axis: Relationships among the vagus nerve, gut microbiota, obesity, and diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2023, 60, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Núñez, S.; Rubín-García, M.; Martín-Sánchez, V.; Álvarez-Álvarez, L.; Molina, A.J. Mediterranean Diet, Obesity-Related Metabolic Cardiovascular Disorders, and Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzamil, H. Elevated Serum TNF-α Is Related to Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Is Associated with Glycemic Control and Insulin Resistance. J. Obes. 2020, 2020, 5076858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A.M.; Hicks, S.B.; Mara, K.C.; Larson, J.J.; Therneau, T.M. The risk of incident extrahepatic cancers is higher in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease than obesity—A longitudinal cohort study. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Park, H.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Jung, K.S.; Lee, M.H.; Jhee, J.H.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, B.S.; et al. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and coronary calcification depending on sex and obesity. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H. Promotion and selection by serum growth factors drive field cancerization, which is anticipated in vivo by type 2 diabetes and obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13927–13931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemat Jouy, S.; Mohan, S.; Scichilone, G.; Mostafa, A.; Mahmoud, A.M. Adipokines in the Crosstalk between Adipose Tissues and Other Organs: Implications in Cardiometabolic Diseases. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, H.J., Jr. The adipocyte as an endocrine organ in the regulation of metabolic homeostasis. Neuropharmacology 2012, 63, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, Y.; Sarkar, D. Association of Adipose Tissue and Adipokines with Development of Obesity-Induced Liver Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.S.; Supriya, R.; Dutheil, F.; Gao, Y. Obesity: Treatments, conceptualizations, and future directions for a growing problem. Biology 2022, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasikiewicz, N.; Myrissa, K.; Hoyland, A.; Lawton, C. Psychological benefits of weight loss following behavioural and/or dietary weight loss interventions. A systematic research review. Appetite 2014, 72, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaseth, J.; Ellefsen, S.; Alehagen, U.; Sundfør, T.M.; Alexander, J. Diets and drugs for weight loss and health in obesity–An update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Quintanar, L.; López Roa, R.I.; Quintero-Fabián, S.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.A.; Vizmanos, B.; Ortuño-Sahagún, D. Phytochemicals That Influence Gut Microbiota as Prophylactics and for the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 9734845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, Z.; Ma, N.; Chen, Z.Y. Beneficial Effects of Dietary Polyphenols on High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity Linking with Modulation of Gut Microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingeo, G.; Brito, A.; Samouda, H.; Iddir, M.; La Frano, M.R.; Bohn, T. Phytochemicals as modifiers of gut microbial communities. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 8444–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.S.; Nayak, A.; Shah, S.; Aich, P. A Systematic Review on the Association between Obesity and Mood Disorders and the Role of Gut Microbiota. Metabolites 2023, 13, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzi, A.; Hassan, A.M.; Zenz, G.; Holzer, P. Diabesity and mood disorders: Multiple links through the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2019, 66, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau-Rodriguez, M.; Tulipani, S.; Isabel Queipo-Ortuño, M.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Tinahones, F.J.; Andres-Lacueva, C. Metabolomic insights into the intricate gut microbial-host interaction in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.X.; Tschöp, M.H. Brain-gut-adipose-tissue communication pathways at a glance. Dis. Model Mech. 2012, 5, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, L.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Knauf, C.; Cani, P.D. Gut microbiota controls adipose tissue expansion, gut barrier and glucose metabolism: Novel insights into molecular targets and interventions using prebiotics. Benef. Microbes 2014, 5, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, J.C.; Matheus, V.A.; Oliveira, R.B.; Tada, S.F.S.; Collares-Buzato, C.B. High-Fat Diet Induces Disruption of the Tight Junction-Mediated Paracellular Barrier in the Proximal Small Intestine Before the Onset of Type 2 Diabetes and Endotoxemia. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 3359–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosy-Westphal, A.; Hägele, F.A.; Müller, M.J. What is the impact of energy expenditure on energy intake? Nutrients 2021, 13, 3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosy-Westphal, A.; Müller, M.J. Diagnosis of obesity based on body composition-associated health risks—Time for a change in paradigm. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Smith, B.; Dahle, J.; Kennedy, S.; Fearnbach, N.; Thomas, D.M.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Müller, M.J. Resting energy expenditure: From cellular to whole-body level, a mechanistic historical perspective. Obesity 2021, 29, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, B.Ø.; Sanchez-Delgado, G.; John, L.M.; Ryan, D.H.; Raun, K.; Ravussin, E. Beyond appetite regulation: Targeting energy expenditure, fat oxidation, and lean mass preservation for sustainable weight loss. Obesity 2022, 30, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Verdejo, R.; Galgani, J. Predictive equations for energy expenditure in adult humans: From resting to free-living conditions. Obesity 2022, 30, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, V.B.I.; Petersen, J.; Lund, J.; Mathiesen, C.V.; Fenselau, H.; Clemmensen, C. Brain control of energy homeostasis: Implications for anti-obesity pharmacotherapy. Cell 2025, 188, 4178–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.K.; Chang, R.B.; Strochlic, D.E.; Umans, B.D.; Lowell, B.B.; Liberles, S.D. Sensory Neurons that Detect Stretch and Nutrients in the Digestive System. Cell 2016, 166, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, B.; Yuan, Y.; Rong, Y.; Pang, R.; Li, Q. Neural and hormonal mechanisms of appetite regulation during eating. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1484827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, A.; Śniegocki, M.; Ziółkowska, E.A. Vagal Oxytocin Receptors as Molecular Targets in Gut–Brain Signaling: Implications for Appetite, Satiety, Obesity, and Esophageal Motility—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, H.R.; Weninger, S.N.; Duca, F.A. Role of the gut–brain axis in energy and glucose metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Martínez-Guardado, I.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Laborde-Cárdenas, C.C.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. The Role of Adipokines in Health and Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, G. Role of hypothalamus function in metabolic diseases and its potential mechanisms. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Castro, F.; Morselli, E.; Claret, M. Interplay between the brain and adipose tissue: A metabolic conversation. EMBO Rep. 2024, 25, 5277–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, L.T.; Park, S.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, K.W.; Kwon, O. Hypothalamic control of energy expenditure and thermogenesis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Bridging inflammation and obesity-associated adipose tissue. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1381227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Assaad, W.; Joly, E.; Barbeau, A.; Sladek, R.; Buteau, J.; Maestre, I.; Pepin, E.; Zhao, S.; Iglesias, J.; Roche, E.; et al. Glucolipotoxicity alters lipid partitioning and causes mitochondrial dysfunction, cholesterol, and ceramide deposition and reactive oxygen species production in INS832/13 ss-cells. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 3061–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opazo-Ríos, L.; Mas, S.; Marín-Royo, G.; Mezzano, S.; Gómez-Guerrero, C.; Moreno, J.A.; Egido, J. Lipotoxicity and Diabetic Nephropathy: Novel Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B.; Tripathy, A.; Archana, P.R.; Kamath, S.U. Unraveling the complexities of diet induced obesity and glucolipid dysfunction in metabolic syndrome. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Vicente, M.; Herranz-López, M. The Interplay Between Oxidative Stress and Lipid Composition in Obesity-Induced Inflammation: Antioxidants as Therapeutic Agents in Metabolic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, G.d.O.; Torrinhas, R.S.; Waitzberg, D.L. Nutrients, physical activity, and mitochondrial dysfunction in the setting of metabolic syndrome. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, D.; Zauli, E.; Celeghini, C.; Previati, M.; Zauli, G. Ceramides as the molecular link between impaired lipid metabolism, saturated fatty acid intake and insulin resistance: Are all saturated fatty acids to be blamed for ceramide-mediated lipotoxicity? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2024, 38, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.-P.; Chan, S.M.; Zeng, X.-Y.; Laybutt, D.R.; Iseli, T.J.; Sun, R.-Q.; Kraegen, E.W.; Cooney, G.J.; Turner, N.; Ye, J.-M. Differing endoplasmic reticulum stress response to excess lipogenesis versus lipid oversupply in relation to hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreckley, E.; Murphy, K.G. The L-Cell in Nutritional Sensing and the Regulation of Appetite. Front. Nutr. 2015, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo-Silgado, M.L.; McRae, A.; Acosta, A. Role of Enteroendocrine Hormones in Appetite and Glycemia. Obes. Med. 2021, 23, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccari, M.C.; Vannucchi, M.G.; Idrizaj, E. The Possible Involvement of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 in the Regulation of Food Intake through the Gut–Brain Axis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriaenssens, A.E.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Distribution and stimulus secretion coupling of enteroendocrine cells along the intestinal tract. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 8, 1603–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, G.; Netto, B.D.M.; Bettini, S.C.; Dâmaso, A.R.; de Freitas, A.C.T. Neuroendocrine regulation of energy balance: Implications on the development and surgical treatment of obesity. Nutr. Health 2017, 23, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, A.; Horner, K.; Johnson, K.O.; Dagbasi, A.; Crabtree, D.R. Appetite-related Gut Hormone Responses to Feeding Across the Life Course. J. Endocr. Soc. 2025, 9, bvae223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumer, J.; Geurts, M.H.; Geurts, V.; Andersson-Rolf, A.; Akkerman, N.; Völlmy, F.; Krueger, D.; Busslinger, G.A.; Martínez-Silgado, A.; Boot, C.; et al. Description and functional validation of human enteroendocrine cell sensors. Science 2024, 386, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, V.B.; Gribble, F.M.; Reimann, F. Nutrient-Induced Cellular Mechanisms of Gut Hormone Secretion. Nutrients 2021, 13, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Zhang, B.; Wu, B.; Xiao, H.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Xu, X.; Li, T. Signaling pathways in obesity: Mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portincasa, P.; Bonfrate, L.; Khalil, M.; Angelis, M.; Calabrese, F.M.; D’Amato, M.; Wang, D.Q.; Di Ciaula, A. Intestinal Barrier and Permeability in Health, Obesity and NAFLD. Biomedicines 2021, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Wang, H.; Du, M.; Zhu, M.J. Maternal obesity induces gut inflammation and impairs gut epithelial barrier function in nonobese diabetic mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMarzooqi, S.K.; Almarzooqi, F.; Sadida, H.Q.; Jerobin, J.; Ahmed, I.; Abou-Samra, A.B.; Fakhro, K.A.; Dhawan, P.; Bhat, A.A.; Al-Shabeeb Akil, A.S. Deciphering the complex interplay of obesity, epithelial barrier dysfunction, and tight junction remodeling: Unraveling potential therapeutic avenues. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolińska, K.; Hułas-Stasiak, M.; Dobrowolska, K.; Sobczyński, J.; Szopa, A.; Tomaszewska, E.; Muszyński, S.; Smoliński, K.; Dobrowolski, P. Effects of an Innovative High-Fat Diet on Intestinal Structure, Barrier Integrity, and Inflammation in a Zebrafish Model of Visceral Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Chen, S.; Lin, L. Research progress of gut microbiota and obesity caused by high-fat diet. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1139800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Barbara, G.; Buurman, W.; Ockhuizen, T.; Schulzke, J.-D.; Serino, M.; Tilg, H.; Watson, A.; Wells, J.M. Intestinal permeability—A new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolfi, C.; Maresca, C.; Monteleone, G.; Laudisi, F. Implication of Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Gut Dysbiosis and Diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Chi, M.M.; Scull, B.P.; Rigby, R.; Schwerbrock, N.M.; Magness, S.; Jobin, C.; Lund, P.K. High-fat diet: Bacteria interactions promote intestinal inflammation which precedes and correlates with obesity and insulin resistance in mouse. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.D.; Franca, E.L.; Fujimori, M.; Silva, S.M.C.; de Marchi, P.G.F.; Deluque, A.L.; Honorio-Franca, A.C.; de Abreu, L.C. Relationship between Proinflammatory Cytokines/Chemokines and Adipokines in Serum of Young Adults with Obesity. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2018, 18, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachliotis, I.D.; Polyzos, S.A. The Intriguing Roles of Cytokines in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Narrative Review. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cybulska, A.M.; Rachubińska, K.; Grochans, E.; Bosiacki, M.; Simińska, D.; Korbecki, J.; Lubkowska, A.; Panczyk, M.; Kuczyńska, M.; Schneider-Matyka, D. Systemic Inflammation Indices, Chemokines, and Metabolic Markers in Perimenopausal Women. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Kaminga, A.C.; Wen, S.W.; Liu, A. Chemokines in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 622438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatterale, F.; Longo, M.; Naderi, J.; Raciti, G.A.; Desiderio, A.; Miele, C.; Beguinot, F. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ballantyne, C.M. Metabolic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J. Mechanisms of insulin resistance in obesity. Front. Med. 2013, 7, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkrinia, E.M.M.; Belančić, A. The Mechanisms of Chronic Inflammation in Obesity and Potential Therapeutic Strategies: A Narrative Review. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabandehloo, H.; Gorgani-Firuzjaee, S.; Panahi, G.; Meshkani, R. Molecular and cellular mechanisms linking inflammation to insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. Transl. Res. 2016, 167, 228–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohallem, R.; Aryal, U.K. Regulators of TNFα mediated insulin resistance elucidated by quantitative proteomics. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mansoori, L.; Al-Jaber, H.; Prince, M.S.; Elrayess, M.A. Role of Inflammatory Cytokines, Growth Factors and Adipokines in Adipogenesis and Insulin Resistance. Inflammation 2022, 45, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragheb, R.; Shanab, G.M.; Medhat, A.M.; Seoudi, D.M.; Adeli, K.; Fantus, I.G. Free fatty acid-induced muscle insulin resistance and glucose uptake dysfunction: Evidence for PKC activation and oxidative stress-activated signaling pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 389, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimu, S.J.; Mahir, J.U.K.; Shakib, F.A.F.; Ridoy, A.A.; Samir, R.A.; Jahan, N.; Hasan, M.F.; Sazzad, S.; Akter, S.; Mohiuddin, M.S.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming Through Polyphenol Networks: A Systems Approach to Metabolic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Lopez, T. Peripheral Inflammation and Insulin Resistance: Their Impact on Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity and Glia Activation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Akash, M.S.H. Mechanisms of inflammatory responses and development of insulin resistance: How are they interlinked? J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, H.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Effects of Des-acyl Ghrelin on Insulin Sensitivity and Macrophage Polarization in Adipose Tissue. J. Transl. Int. Med. 2021, 9, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, Y.; He, S.; Tan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zheng, W. Macrophages, Chronic Inflammation, and Insulin Resistance. Cells 2022, 11, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglov, V.; Jang, I.H.; Camell, C.D. Inflammaging and fatty acid oxidation in monocytes and macrophages. Immunometabolism 2024, 6, e00038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.A.D.S.; da Silva, F.C.; de Moraes-Vieira, P.M.M. The Impact of Ghrelin in Metabolic Diseases: An Immune Perspective. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 4527980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.B.; Prodonoff, J.S.; Favero de Aguiar, C.; Correa-da-Silva, F.; Castoldi, A.; Bakker, N.V.T.; Davanzo, G.G.; Castelucci, B.; Pereira, J.A.D.S.; Curtis, J.; et al. Leptin Signaling Suppression in Macrophages Improves Immunometabolic Outcomes in Obesity. Diabetes 2022, 71, 1546–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, L.; Pereira, J.A.D.S.; Palhinha, L.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M.M. Leptin in the regulation of the immunometabolism of adipose tissue-macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 106, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wan, R.; Hu, C. Leptin/obR signaling exacerbates obesity-related neutrophilic airway inflammation through inflammatory M1 macrophages. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Yan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Yu, S.; Fu, J.; Liu, Y.; Su, J. Macrophage Polarization Mediated by Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induces Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, H.; Sun, W.; Yi, Q. The role of AMPK in macrophage metabolism, function and polarisation. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witcoski Junior, L.; de Lima, J.D.; Somensi, A.G.; de Souza Santos, L.B.; Paschoal, G.L.; Uada, T.S.; Bastos, T.S.B.; de Paula, A.G.P.; Dos Santos Luz, R.B.; Czaikovski, A.P.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming of macrophages in the context of type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Huang, Y.; He, B. New Insights into Adipose Tissue Macrophages in Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Cells 2022, 11, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galic, S.; Fullerton, M.D.; Schertzer, J.D.; Sikkema, S.; Marcinko, K.; Walkley, C.R.; Izon, D.; Honeyman, J.; Chen, Z.P.; van Denderen, B.J.; et al. Hematopoietic AMPK β1 reduces mouse adipose tissue macrophage inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4903–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, K.; Lehrke, M.; Parhofer, K.G.; Broedl, U.C. Adipokines and insulin resistance. Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; He, C.; Li, L.; You, M.; Wang, L.; Cao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; et al. Cx43 acts as a mitochondrial calcium regulator that promotes obesity by inducing the polarization of macrophages in adipose tissue. Cell. Signal 2023, 105, 110606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Saha, A.; An, S.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, H.; Noh, M.; Lee, Y.H. Macrophage-Specific Connexin 43 Knockout Protects Mice from Obesity-Induced Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 925971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Casanova, J.E.; Durán-Agüero, S.; Caro-Fuentes, N.J.; Gamboa-Arancibia, M.E.; Bruna, T.; Bermúdez, V.; Rojas-Gómez, D.M. New Insights on the Role of Connexins and Gap Junctions Channels in Adipose Tissue and Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.K.; Steinberg, G.R. AMPK and the Endocrine Control of Metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 910–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmas, C.E.; Bousvarou, M.D.; Kostara, C.E.; Papakonstantinou, E.J.; Salamou, E.; Guzman, E. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 3000605231164548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormazabal, V.; Nair, S.; Elfeky, O.; Aguayo, C.; Salomon, C.; Zuñiga, F.A. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, M.M.; Jeelani, M.; Alharthi, M.H.; Rizvi, S.F.; Sohail, S.K.; Wani, J.I.; Sabah, Z.U.; BinAfif, W.F.; Nandi, P.; Alshahrani, A.M.; et al. Unraveling the Mystery of Insulin Resistance: From Principle Mechanistic Insights and Consequences to Therapeutic Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Xie, Q.; Pan, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Peng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Tong, N. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: Pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, P.; Pratima, P.; Gaidhane, A.M.; Vadia, N.; Menon, S.V.; Chennakesavulu, K.; Panigrahi, R.; Shabil, M.; Jena, D.; Kumar, H.; et al. Prevalence and impact of microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus on cognitive impairment and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Diabetes-Induced Macrovascular and Microvascular Complications: The Role of Oxidative Stress. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, M.; Singh, J. Endothelial dysfunction and platelet hyperactivity in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Molecular insights and therapeutic strategies. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Bui, H.D.; Jing, X.; Lu, R.; Chen, J.; Ngo, V.; Cui, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Ma, J. Prevalence of and factors related to microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Tianjin, China: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.V.; Shaw, L.C.; Grant, M.B. Inflammation in the pathogenesis of microvascular complications in diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2012, 3, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruhashi, T.; Higashi, Y. Pathophysiological Association between Diabetes Mellitus and Endothelial Dysfunction. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brie, A.D.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Popescu, R.; Adam, O.; Tîrziu, A.; Brie, D.M. Atherosclerosis and Insulin Resistance: Is There a Link Between Them? Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, W.B.; Love, K.M.; Gregory, J.M.; Liu, Z.; Barrett, E.J. Metabolic and vascular insulin resistance: Partners in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease in diabetes. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2025, 328, H1218–H1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornfeldt, K.E.; Tabas, I. Insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Shruthi, N.R.; Banerjee, A.; Jothimani, G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Pathak, S. Endothelial dysfunction, platelet hyperactivity, hypertension, and the metabolic syndrome: Molecular insights and combating strategies. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1221438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, S.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Husain, M.; Ahima, R.; Arca, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Diehl, A.M.; Fontana, L.; Foo, R.; Frühbeck, G.; et al. Clinical staging to guide management of metabolic disorders and their sequelae: A European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 3685–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripuram, C.; Gunde, A.K.; Hegde, S.V.; Ghetia, K.S.; Kandimalla, R.; Ghetia, K. Exploring Cardiovascular Health: The Role of Dyslipidemia and Inflammation. Cureus 2025, 17, e78818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hefnawy, K.A.; Elsaid, H.H. Assessment of some inflammatory markers and lipid profile as risk factors for atherosclerosis in subclinical hypothyroid patients. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 31, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, A.; De Michele, G.; Fimiani, F.; Acerbo, V.; Scherillo, G.; Signore, G.; Rotolo, F.P.; Scialla, F.; Raucci, G.; Panico, D.; et al. Visceral adipose tissue and residual cardiovascular risk: A pathological link and new therapeutic options. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1187735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutheil, F.; Gordon, B.A.; Naughton, G.; Crendal, E.; Courteix, D.; Chaplais, E.; Thivel, D.; Lac, G.; Benson, A.C. Cardiovascular risk of adipokines: A review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 2082–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Fuster, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines: A link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feijóo-Bandín, S.; Aragón-Herrera, A.; Moraña-Fernández, S.; Anido-Varela, L.; Tarazón, E.; Roselló-Lletí, E.; Portolés, M.; Moscoso, I.; Gualillo, O.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; et al. Adipokines and Inflammation: Focus on Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuster, J.J.; Ouchi, N.; Gokce, N.; Walsh, K. Obesity-Induced Changes in Adipose Tissue Microenvironment and Their Impact on Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1786–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis, G. Epicardial adipose tissue in contemporary cardiology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancusi, C.; Izzo, R.; di Gioia, G.; Losi, M.A.; Barbato, E.; Morisco, C. Insulin Resistance the Hinge Between Hypertension and Type 2 Diabetes. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2020, 27, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.S.; Wang, A.; Yu, H. Link between insulin resistance and hypertension: What is the evidence from evolutionary biology? Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2014, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Haque, M. Insulin Resistance Is Cheerfully Hitched with Hypertension. Life 2022, 12, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornstad, P.; Eckel, R.H. Pathogenesis of Lipid Disorders in Insulin Resistance: A Brief Review. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2018, 18, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Ginsberg, H.N. Increased very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 22, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, J.; Scheja, L. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and lipoprotein metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2021, 50, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, H.; Adachi, H.; Hakoshima, M.; Katsuyama, H. Postprandial Hyperlipidemia: Its Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Atherogenesis, and Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergès, B.; Vantyghem, M.-C.; Reznik, Y.; Duvillard, L.; Rouland, A.; Capel, E.; Vigouroux, C. Hypertriglyceridemia Results From an Impaired Catabolism of Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins in PLIN1-Related Lipodystrophy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergès, B. Pathophysiology of diabetic dyslipidaemia: Where are we? Diabetologia 2015, 58, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, H.E.; Kirkpatrick, C.F.; Maki, K.C.; Toth, P.P.; Morgan, R.T.; Tondt, J.; Christensen, S.M.; Dixon, D.L.; Jacobson, T.A. Obesity, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease: A joint expert review from the Obesity Medicine Association and the National Lipid Association 2024. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2024, 18, e320–e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcover, S.; Ramos-Regalado, L.; Girón, G.; Muñoz-García, N.; Vilahur, G. HDL-Cholesterol and Triglycerides Dynamics: Essential Players in Metabolic Syndrome. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, L.; Wang, X.M. The link between hyperuricemia and diabetes: Insights from a quantitative analysis of scientific literature. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1441503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deji-Oloruntoba, O.O.; Balogun, J.O.; Elufioye, T.O.; Ajakwe, S.O. Hyperuricemia and Insulin Resistance: Interplay and Potential for Targeted Therapies. Int. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma Sakalli, A.; Küçükerdem, H.S.; Aygün, O. What is the relationship between serum uric acid level and insulin resistance?: A case-control study. Medicine 2023, 102, e36732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Lan, L.; Qu, R.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, R.; Na, L.; Sun, C. Temporal Relationship Between Hyperuricemia and Insulin Resistance and Its Impact on Future Risk of Hypertension. Hypertension 2017, 70, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Xie, L.; Yang, B.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, Z.; Gao, J. Hyperuricemia and its related diseases: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.W.; Ahn, I.S.; Wang, S.S.; Majid, S.; Diamante, G.; Cely, I.; Zhang, G.; Cabanayan, A.; Komzyuk, S.; Bonnett, J.; et al. Multitissue single-cell analysis reveals differential cellular and molecular sensitivity between fructose and high-fat high-sucrose diets. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Du, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, C. Association of serum uric acid with indices of insulin resistance: Proposal of a new model with reference to gender differences. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 3783–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Rong, S.; Wang, Q.; Sun, T.; Bao, W.; Chen, L.; Liu, L. Association between plasma uric acid and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: A Mendelian randomization analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 171, 108542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armandi, A.; Rosso, C.; Caviglia, G.P.; Bugianesi, E. Insulin Resistance across the Spectrum of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Metabolites 2021, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grander, C.; Grabherr, F.; Tilg, H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathophysiological concepts and treatment options. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Vachher, M.; Arora, T.; Kumar, B.; Burman, A. Visceral fat: A key mediator of NAFLD development and progression. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 33, 200210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiseler, M.; Schwabe, R.; Hampe, J.; Kubes, P.; Heikenwaelder, M.; Tacke, F. Immune mechanisms linking metabolic injury to inflammation and fibrosis in fatty liver disease–novel insights into cellular communication circuits. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1136–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wal, P.; Yadav, S.; Jha, S.K.; Singh, A.; Bhargavi, B.; Shivaram, R.; Imran, M.; Aziz, N. Role of natural compounds in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD): A mechanistic approach. Egypt. Liver J. 2025, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, A.; Negrea, M.O.; Cipăian, C.R.; Boicean, A.; Mihaila, R.; Rezi, C.; Cristinescu, B.A.; Berghea-Neamtu, C.S.; Popa, M.L.; Teodoru, M.; et al. Interactions between Metabolic Syndrome, MASLD, and Arterial Stiffening: A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecani, M.; Andreozzi, P.; Cangemi, R.; Corica, B.; Miglionico, M.; Romiti, G.F.; Stefanini, L.; Raparelli, V.; Basili, S. Metabolic Syndrome and Liver Disease: Re-Appraisal of Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment Through the Paradigm Shift from NAFLD to MASLD. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Heterogeneous pathomechanisms and effectiveness of metabolism-based treatment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacke, F.; Horn, P.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Ratziu, V.; Bugianesi, E.; Francque, S.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Valenti, L.; Roden, M.; Schick, F.; et al. EASL–EASD–EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 492–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, A.A.; Ahmad, M.N.; Ghabashi, M.A.; Alazzeh, A.Y.; Habib, S.M.; Abu Al-Haijaa, D.; Azzeh, F.S. Developmental Trends of Metabolic Syndrome in the Past Two Decades: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Matos, A.F.; Valério, C.M.; Júnior, W.S.S.; de Araujo-Neto, J.M.; Sposito, A.C.; Suassuna, J.H.R. CARDIAL-MS (CArdio-Renal-DIAbetes-Liver-Metabolic Syndrome): A new proposition for an integrated multisystem metabolic disease. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyüncü, N.; Erol, Ç. From Metabolic Syndrome to Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Syndrome and Systemic Metabolic Disorder: A Call to Recognize the Progressive Multisystemic Dysfunction. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2025, 29, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, S.; Pheiffer, C.; Johnson, R.; Louw, J.; Muller, C.J.F. Intestinal Barrier Function and Immune Homeostasis Are Missing Links in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Development. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 833544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebi, M.; Yilmaz, Y. Epithelial barrier hypothesis in the context of nutrition, microbial dysbiosis, and immune dysregulation in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1575770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondinella, D.; Raoul, P.C.; Valeriani, E.; Venturini, I.; Cintoni, M.; Severino, A.; Galli, F.S.; Mora, V.; Mele, M.C.; Cammarota, G.; et al. The Detrimental Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on the Human Gut Microbiome and Gut Barrier. Nutrients 2025, 17, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti; Dey, P. Mechanisms and implications of the gut microbial modulation of intestinal metabolic processes. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2025, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Riva, A. Intestinal Barrier Function in Health and Disease—Any Role of SARS-CoV-2? Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifarelli, V.; Peche, V.S.; Abumrad, N.A. Vascular and lymphatic regulation of gastrointestinal function and disease risk. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2022, 1867, 159207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yu, X.; Novák, P.; Gui, Q.; Yin, K. Enhancing intestinal barrier efficiency: A novel metabolic diseases therapy. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1120168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.S.; Ghosh, S. Intestinal Barrier Function—A Novel Target to modulate Diet-induced Metabolic Diseases. Arch. Gastroenterol. Res. 2020, 1, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, K.; Seo, J.; Yeun, J.; Choi, H.; Kim, Y.I.; Chang, S.Y. The role of mucosal barriers in human gut health. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2021, 44, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemtov, S.J.; Emani, R.; Bielska, O.; Covarrubias, A.J.; Verdin, E.; Andersen, J.K.; Winer, D.A. The intestinal immune system and gut barrier function in obesity and ageing. FEBS J. 2023, 290, 4163–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.S.; Wang, J.; Yannie, P.J.; Ghosh, S. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction, LPS Translocation, and Disease Development. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvz039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso, N.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Intestinal Barrier in Human Health and Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohr, M.W.; Narasimhulu, C.A.; Rudeski-Rohr, T.A.; Parthasarathy, S. Negative Effects of a High-Fat Diet on Intestinal Permeability: A Review. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, J.; Connolly, L.; Stewart, L.D. Increased Intestinal Permeability: An Avenue for the Development of Autoimmune Disease? Expo. Health 2024, 16, 575–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytriv, T.R.; Storey, K.B.; Lushchak, V.I. Intestinal barrier permeability: The influence of gut microbiota, nutrition, and exercise. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1380713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollander, D.; Kaunitz, J.D. The “Leaky Gut”: Tight Junctions but Loose Associations? Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, T.P.M.; Rampanelli, E.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Vallance, B.A.; Verchere, C.B.; van Raalte, D.H.; Herrema, H. Gut Microbiota as a Trigger for Metabolic Inflammation in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 571731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulangé, C.L.; Neves, A.L.; Chilloux, J.; Nicholson, J.K.; Dumas, M.E. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Durán, E.; García-Galindo, J.J.; López-Murillo, L.D.; Huerta-Huerta, A.; Balleza-Alejandri, L.R.; Beltrán-Ramírez, A.; Anaya-Ambriz, E.J.; Suárez-Rico, D.O. Microbiota and Inflammatory Markers: A Review of Their Interplay, Clinical Implications, and Metabolic Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciarino, A.; Diwakarla, S.; Handreck, J.; Bergola, C.; Sahakian, L.; McQuade, R.M. The role of the gastrointestinal barrier in obesity-associated systemic inflammation. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohm, T.V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelc, A.; Fic, W.; Typrowicz, T.; Polak-Szczybyło, E. Physiological Mechanisms of and Therapeutic Approaches to the Gut Microbiome and Low-Grade Inflammation in Obesity. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portincasa, P.; Khalil, M.; Graziani, A.; Frühbeck, G.; Baffy, G.; Garruti, G.; Di Ciaula, A.; Bonfrate, L. Gut microbes in metabolic disturbances. Promising role for therapeutic manipulations? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 119, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patloka, O.; Komprda, T.; Franke, G. Review of the Relationships Between Human Gut Microbiome, Diet, and Obesity. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakaroun, R.M.; Massier, L.; Kovacs, P. Gut Microbiome, Intestinal Permeability, and Tissue Bacteria in Metabolic Disease: Perpetrators or Bystanders? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.N.; Barber, T.; Renshaw, D.; Farnaud, S.; Oduro-Donkor, D.; Turner, M.C. Associations between the gut microbiome and metabolic, inflammatory, and appetitive effects of sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cong, Y. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites in the regulation of host immune responses and immune-related inflammatory diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks, M.G.; Garrett, W.S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yang Lee, B.J.; Wang, T.; Xiang, X.; Tan, Y.; Han, Y.; Bi, Y.; Zhi, F.; Wang, X.; He, F.; et al. Microbiota, chronic inflammation, and health: The promise of inflammatome and inflammatomics for precision medicine and health care. hLife 2025, 3, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.S.; Mak, W.Q.; Tan, L.K.S.; Ng, C.X.; Chan, H.H.; Yeow, S.H.; Foo, J.B.; Ong, Y.S.; How, C.W.; Khaw, K.Y. Microbiota–gut–brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pi, Y.; Fang, M.; Li, Y.; Cai, L.; Han, R.; Sun, W.; Jiang, X.; Chen, L.; Du, J.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Interactions between Gut Microbiota and Natural Bioactive Polysaccharides in Metabolic Diseases: Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, M.; Madsen, K.L. Immunometabolism and microbial metabolites at the gut barrier: Lessons for therapeutic intervention in inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2023, 16, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tang, X.; He, X.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, L. A Comprehensive Review of the Role of the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis via Neuroinflammation: Advances and Therapeutic Implications for Ischemic Stroke. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, H.; Chen, P.; Xie, H.; Tao, Y. Demystifying the manipulation of host immunity, metabolism, and extraintestinal tumors by the gut microbiome. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.; Robinson, B.L.; Houston, K.; Sangay, A.R.V.; Saadeh, M.; D’Souza, S.; Johnson, D.A. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites and chronic inflammatory diseases. Explor. Med. 2025, 6, 1001275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasaly, N.; De Vos, P.; Hermoso, M.A. Impact of bacterial metabolites on gut barrier function and host immunity: A focus on bacterial metabolism and its relevance for intestinal inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 658354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-A.; Gu, W.; Lee, I.-A.; Joh, E.-H.; Kim, D.-H. High fat diet-induced gut microbiota exacerbates inflammation and obesity in mice via the TLR4 signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, S.; Thiemermann, C. Role of Metabolic Endotoxemia in Systemic Inflammation and Potential Interventions. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 594150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.R.; Arthur, S.; Haynes, J.; Butts, M.R.; Nepal, N.; Sundaram, U. The Role of Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in Obesity-Associated Chronic Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, E.E.; Jocken, J.W.; Blaak, E.E. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Gut microbiome and health: Mechanistic insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Van Hul, M. Gut microbiota in overweight and obesity: Crosstalk with adipose tissue. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-T.; Mills, D.A. Exploring the gut microbiome: Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics as key players in human health and disease improvement. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 2065–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Tang, C.; Hu, G.; Gao, Z. Targeting gut microbiota as a therapeutic target in T2DM: A review of multi-target interactions of probiotics, prebiotics, postbiotics, and synbiotics with the intestinal barrier. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 210, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, M.K.; Kumari, I.; Singh, B.; Sharma, K.K.; Tiwari, S.K. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics: Safe options for next-generation therapeutics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-González, C.; Alonso-Peña, M.; Argos Vélez, P.; Crespo, J.; Iruzubieta, P. Unraveling MASLD: The Role of Gut Microbiota, Dietary Modulation, and AI-Driven Lifestyle Interventions. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Borromeo, S.; Cavioni, A.; Gasparri, C.; Gattone, I.; Genovese, E.; Lazzarotti, A.; Minonne, L.; Moroni, A.; Patelli, Z.; et al. Therapeutic Strategies to Modulate Gut Microbial Health: Approaches for Chronic Metabolic Disorder Management. Metabolites 2025, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Cui, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. The oral-gut microbiota axis: A link in cardiometabolic diseases. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiners, F.; Fuellen, G.; Barrantes, I. Gut microbiome-mediated health effects of fiber and polyphenol-rich dietary interventions. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1647740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, O.; Proczko-Stepaniak, M.; Mika, A. Short-Chain Fatty Acids-A Product of the Microbiome and Its Participation in Two-Way Communication on the Microbiome-Host Mammal Line. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.A.; Inniss, S.; Kumagai, T.; Rahman, F.Z.; Smith, A.M. The Role of Diet and Gut Microbiota in Regulating Gastrointestinal and Inflammatory Disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 866059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münte, E.; Hartmann, P. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Other Metabolic Diseases. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.K.; Macia, L.; Mackay, C.R. Dietary fiber and SCFAs in the regulation of mucosal immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Montero, C.; Fraile-Martínez, O.; Gómez-Lahoz, A.M.; Pekarek, L.; Castellanos, A.J.; Noguerales-Fraguas, F.; Coca, S.; Guijarro, L.G.; García-Honduvilla, N.; Asúnsolo, A.; et al. Nutritional Components in Western Diet Versus Mediterranean Diet at the Gut Microbiota–Immune System Interplay. Implications for Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Jian, Y.-P.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.-T.; Sun, H.-H.; Liu, M.-D.; Zhou, H.-L.; Wang, Y.-S.; Xu, Z.-X. Short-chain fatty acids in diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, E.R.; Lam, Y.K.; Uhlig, H.H. Short-chain fatty acids: Linking diet, the microbiome and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Su, Z.; Wang, S. The anti-obesity effects of polyphenols: A comprehensive review of molecular mechanisms and signal pathways in regulating adipocytes. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1393575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deledda, A.; Annunziata, G.; Tenore, G.C.; Palmas, V.; Manzin, A.; Velluzzi, F. Diet-Derived Antioxidants and Their Role in Inflammation, Obesity and Gut Microbiota Modulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randeni, N.; Luo, J.; Xu, B. Critical Review on Anti-Obesity Effects of Anthocyanins Through PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathways. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Lei, J.; Zhong, J.; Wang, B.; Wan, Y.; Li, J.; Liao, C.; He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ito, K. Kaempferol reduces obesity, prevents intestinal inflammation, and modulates gut microbiota in high-fat diet mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 99, 108840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, J.; Abraão, A.; Gouvinhas, I.; Granato, D.; Barros, A.N. Advances in Leaf Plant Bioactive Compounds: Modulation of Chronic Inflammation Related to Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cardoso, K.; Ginés, I.; Pinent, M.; Ardévol, A.; Blay, M.; Terra, X. Effects of flavonoids on intestinal inflammation, barrier integrity and changes in gut microbiota during diet-induced obesity. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2016, 29, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, A.; Samuel, S.M.; Mohamed, A.; Wani, M.Y.; Ghorbel, S.; Miled, N.; Büsselberg, D.; Chaari, A. Role of flavonoids in controlling obesity: Molecular targets and mechanisms. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1177897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, H.; Olaolu, O.A.; Ibrahim, S.; Ibrahim, S.; Wang, S. Natural Products: A Dependable Source of Therapeutic Alternatives for Inflammatory Bowel Disease through Regulation of Tight Junctions. Molecules 2023, 28, 6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.X.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, Z.J.; Wang, J.F. Quercetin effectively improves LPS-induced intestinal inflammation, pyroptosis, and disruption of the barrier function through the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway in vivo and in vitro. Food Nutr. Res. 2022, 66, 10-29219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, C.; Min, S.; Li, B.; Lu, Y.; Cao, B.; Su, H.; He, Y. Recent advances in flavonoids benefiting intestinal homeostasis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 165, 105311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Gomes, C.; Nunes, F.M.; Silva, A.M. Natural Products as Dietary Agents for the Prevention and Mitigation of Oxidative Damage and Inflammation in the Intestinal Barrier. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho-Wolino, K.S.; Almeida, P.P.; Mafra, D.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B. Bioactive compounds modulating Toll-like 4 receptor (TLR4)-mediated inflammation: Pathways involved and future perspectives. Nutr. Res. 2022, 107, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F.; Artis, D.; Becker, C. The intestinal barrier: A pivotal role in health, inflammation, and cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 10, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, R.; Ke, R.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y. Intestinal Barrier in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms and Treatment. J. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2025, 3, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, S. Chinese Medicine-Derived Natural Compounds and Intestinal Regeneration: Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. SAA1 Promotes Ulcerative Colitis and Activating Colonic TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 Signaling Pathway. Inflammation 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Zhong, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, P.; Liu, Z. Rhein protects against barrier disruption and inhibits inflammation in intestinal epithelial cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 71, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; Zheng, B.; Shi, D.; Qiu, F. Glycyrol Relieves Ulcerative Colitis by Promoting the Fusion of ZO-1 with the Cell Membrane through the Enteric Glial Cells GDNF/RET Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 14653–14662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakadate, K.; Ito, N.; Kawakami, K.; Yamazaki, N. Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Plant-Derived Compounds and Prevention of Chronic Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizadeh, F.; Karav, S.; Sahebkar, A. Phytochemicals as Modulators of NETosis: A Comprehensive Review on Their Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Phytother. Res. 2025, 39, 3545–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; C, M.; Kumarasamy, M. Natural products as potential modulators of pro-inflammatory cytokines signalling in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. Integr. 2024, 5, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.; Yang, J.; Cao, M.; Xu, T.; He, J.; Hong, H.; Jiang, L.; Peng, S.; Xiong, P. Advancements in nasal drug delivery system of natural products. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1667517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Li, N. Research Progress on Natural Products Alleviating Liver Inflammation and Fibrosis via NF-κB Pathway. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202402248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahomoodally, M.F.; Aumeeruddy, M.Z.; Legoabe, L.J.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Zengin, G. Plants’ bioactive secondary metabolites in the management of sepsis: Recent findings on their mechanism of action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1046523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, J.; Luo, W.; Kuang, T. Natural products for intervertebral disc degeneration: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic potentials. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1605764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sitarek, P.; Śliwiński, T.; Zajdel, R. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Extracts and Pure Compounds Derived from Plants via Modulation of Signaling Pathways, Especially PI3K/AKT in Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, W.; Duan, C.; Sheng, J.; Tian, Y.; Peng, L.; Gao, X. Amomum tsaoko flavonoids attenuate ulcerative colitis by inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway and modulating gut microbiota in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1557778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Ma, N.; Gao, Y.F.; Sun, L.L.; Zhang, J.G. Therapeutic effects of 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, and 10-gingerol on dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute ulcerative colitis in rats. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Noh, E.-M.; Kim, S.-Y. Anti-inflammatory effect and signaling mechanism of 8-shogaol and 10-shogaol in a dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis mouse model. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, J.Y. Ginger attenuates inflammation in a mouse model of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 1493–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayvaz, H.; Cabaroglu, T.; Akyildiz, A.; Pala, C.U.; Temizkan, R.; Ağçam, E.; Ayvaz, Z.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Direito, R.; et al. Anthocyanins: Metabolic Digestion, Bioavailability, Therapeutic Effects, Current Pharmaceutical/Industrial Use, and Innovation Potential. Antioxidants 2022, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaru, B.; Drețcanu, G.; Pop, T.D.; Stǎnilǎ, A.; Diaconeasa, Z. Anthocyanins: Factors Affecting Their Stability and Degradation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Z.; Tang, S.; Li, Z.; Chou, S.; Shu, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Tian, J.; et al. An updated review on the stability of anthocyanins regarding the interaction with food proteins and polysaccharides. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4378–4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiloglu, S.; Capanoglu, E.; Grootaert, C.; Van Camp, J. Anthocyanin Absorption and Metabolism by Human Intestinal Caco-2 Cells—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 21555–21574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tian, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y. Anthocyanins, Anthocyanin-Rich Berries, and Cardiovascular Risks: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 44 Randomized Controlled Trials and 15 Prospective Cohort Studies. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 747884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.H.; Hwang, I.G.; Lee, Y.M. Effects of anthocyanin supplementation on blood lipid levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1207751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Liang, J.; Xue, Z.; Meng, X.; Jia, L. Effect of dietary anthocyanins on the risk factors related to metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0315504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Li, J. Association of dietary anthocyanidins intake with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular diseases mortality in USA adults: A prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Ling, W.; Du, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Deng, S.; Liu, Z. Effects of Anthocyanins on Cardiometabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eker, M.E.; Aaby, K.; Budic-Leto, I.; Brnčić, S.R.; El, S.N.; Karakaya, S.; Simsek, S.; Manach, C.; Wiczkowski, W.; Pascual-Teresa, S. A Review of Factors Affecting Anthocyanin Bioavailability: Possible Implications for the Inter-Individual Variability. Foods 2019, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ferrars, R.M.; Czank, C.; Zhang, Q.; Botting, N.P.; Kroon, P.A.; Cassidy, A.; Kay, C.D. The pharmacokinetics of anthocyanins and their metabolites in humans. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 3268–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. Some anthocyanins could be efficiently absorbed across the gastrointestinal mucosa: Extensive presystemic metabolism reduces apparent bioavailability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3904–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speciale, A.; Cimino, F.; Saija, A.; Canali, R.; Virgili, F. Bioavailability and molecular activities of anthocyanins as modulators of endothelial function. Genes Nutr. 2014, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavéra, S.; Felgines, C.; Texier, O.; Besson, C.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Lamaison, J.L.; Rémésy, C. Anthocyanin metabolism in rats and their distribution to digestive area, kidney, and brain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3902–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W. Anthocyanins and Their C. Molecules 2019, 24, 4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W.; Blumberg, J.B.; McDonald, J.E.; Vinqvist-Tymchuk, M.R.; Fillmore, S.A.; Graf, B.A.; O’Leary, J.M.; Milbury, P.E. Identification of anthocyanins in the liver, eye, and brain of blueberry-fed pigs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiyanagi, T.; Shida, Y.; Rahman, M.M.; Hatano, Y.; Konishi, T. Bioavailability and tissue distribution of anthocyanins in bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) extract in rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6578–6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyimba, T.; Yiga, P.; Bamuwamye, M.; Ogwok, P.; Van der Schueren, B.; Matthys, C. Efficacy of Dietary Polyphenols from Whole Foods and Purified Food Polyphenol Extracts in Optimizing Cardiometabolic Health: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.M.; Hobden, M.R.; Brown, K.D.; Farrimond, J.; Targett, D.; Corpe, C.P.; Ellis, P.R.; Todorova, Y.; Socha, K.; Bahsoon, S.; et al. Acute effects of drinks containing blackcurrant and citrus (poly)phenols and dietary fibre on postprandial glycaemia, gut hormones, cognitive function and appetite in healthy adults: Two randomised controlled trials. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 10163–10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favari, C.; Rinaldi de Alvarenga, J.F.; Sánchez-Martínez, L.; Tosi, N.; Mignogna, C.; Cremonini, E.; Manach, C.; Bresciani, L.; Del Rio, D.; Mena, P. Factors driving the inter-individual variability in the metabolism and bioavailability of (poly)phenolic metabolites: A systematic review of human studies. Redox Biol. 2024, 71, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitali Čepo, D.; Radić, K.; Turčić, P.; Anić, D.; Komar, B.; Šalov, M. Food (Matrix) Effects on Bioaccessibility and Intestinal Permeability of Major Olive Antioxidants. Foods 2020, 9, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verediano, T.A.; Stampini Duarte Martino, H.; Dias Paes, M.C.; Tako, E. Effects of Anthocyanin on Intestinal Health: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igwe, E.O.; Charlton, K.E.; Probst, Y.C.; Kent, K.; Netzel, M.E. A systematic literature review of the effect of anthocyanins on gut microbiota populations. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 32, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tang, Z.; Herrera-Balandrano, D.D.; Qiu, Z.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W. In vitro fermentation characteristics of blueberry anthocyanins and their impacts on gut microbiota from obese human. Food Res. Int. 2024, 176, 113761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, E.; Day-Walsh, P.; Kellingray, L.; Narbad, A.; Kroon, P.A. Spontaneous and Microbiota-Driven Degradation of Anthocyanins in an In Vitro Human Colon Model. Mol. Nutr. Food. Res. 2023, 67, e2300036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Zhang, L.; Liao, Y.; Lin, Z.; Guo, C.; Luo, S.; Wang, F.; Zou, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, C.; et al. Semaglutide alleviates gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by a high-fat diet. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 969, 176440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Gong, W.; Yang, F.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, G.; Gan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide alleviates hepatic steatosis and modulates gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism in diabetic mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 147, 113937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lin, Z.; He, M.; Liao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, C.; Duan, X.; Jiang, X.; Qiu, J. The role of gut microbiota in Tirzepatide-mediated alleviation of high-fat diet-induced obesity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1002, 177827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Teng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, S. Effects of semaglutide on gut microbiota, cognitive function and inflammation in obese mice. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, C.; Wu, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Ding, X. Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Gut Microbiota in Dehydroepiandrosterone-Induced Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Mice: Compared Evaluation of Liraglutide and Semaglutide Intervention. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 865–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, P.; Tiwari, A.; Sharma, S.; Tiwari, V.; Sheoran, B.; Ali, U.; Garg, M. Effect of anthocyanins on gut health markers, Firmicutes-Bacteroidetes ratio and short-chain fatty acids: A systematic review via meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Akshit, F.N.U.; Mohan, M.S. Effects of anthocyanin supplementation in diet on glycemic and related cardiovascular biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1199815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, K.S.; den Hartigh, L.J. Modulation of Adipocyte Metabolism by Microbial Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.R.; Singh, S.; Hwang, H.S.; Seo, S.O. Using Gut Microbiota Modulation as a Precision Strategy Against Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.W.; Lü, H.; Du, L.L.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H.F.; Wu, W.L.; Chen, J.; Li, W.L. Five blueberry anthocyanins and their antioxidant, hypoglycemic, and hypolipidemic effects in vitro. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1172982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Acosta, M.L.; Smith, L.; Miller, R.J.; McCarthy, D.I.; Farrimond, J.A.; Hall, W.L. Drinks containing anthocyanin-rich blackcurrant extract decrease postprandial blood glucose, insulin and incretin concentrations. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 38, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Mathai, M.L.; Xu, G.; Su, X.Q.; McAinch, A.J. The effect of dietary supplementation with blueberry, cyanidin-3-O-β-glucoside, yoghurt and its peptides on gene expression associated with glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle obtained from a high-fat-high-carbohydrate diet induced obesity model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Vargas, M.; Sandoval-Rodriguez, A.; Rodriguez-Echevarria, R.; Dominguez-Rosales, J.A.; Santos-Garcia, A.; Armendariz-Borunda, J. Delphinidin Ameliorates Hepatic Triglyceride Accumulation in Human HepG2 Cells, but Not in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teparak, C.; Uriyapongson, J.; Phoemsapthawee, J.; Tunkamnerdthai, O.; Aneknan, P.; Tong-Un, T.; Panthongviriyakul, C.; Leelayuwat, N.; Alkhatib, A. Diabetes Therapeutics of Prebiotic Soluble Dietary Fibre and Antioxidant Anthocyanin Supplement in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Randomised Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumuzachi, O.; Mocan, A.; Rohn, S.; Gavrilaș, L. Impact of a Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa (Michx.) Elliott) Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Critical Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyestani, T.R.; Yari, Z.; Rasekhi, H.; Nikooyeh, B. How effective are anthocyanins on healthy modification of cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Conesa, M.-T.; Chambers, K.; Combet, E.; Pinto, P.; Garcia-Aloy, M.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; de Pascual-Teresa, S.; Mena, P.; Konic Ristic, A.; Hollands, W.J. Meta-analysis of the effects of foods and derived products containing ellagitannins and anthocyanins on cardiometabolic biomarkers: Analysis of factors influencing variability of the individual responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Vital, D.; Luzardo-Ocampo, I.; Cuellar-Nuñez, M.L.; Loarca-Piña, G.; de Mejia, E.G. Maize extract rich in ferulic acid and anthocyanins prevents high-fat-induced obesity in mice by modulating SIRT1, AMPK and IL-6 associated metabolic and inflammatory pathways. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 79, 108343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFuria, J.; Bennett, G.; Strissel, K.J.; James, W.P.; Milbury, P.E.; Greenberg, A.S.; Obin, M.S. Dietary Blueberry Attenuates Whole-Body Insulin Resistance in High Fat-Fed Mice by Reducing Adipocyte Death and Its Inflammatory Sequelae. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1510–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Wu, X.; Gu, L.; Hager, T.J.; Hager, A.; Howard, L.R. Whole Berries versus Berry Anthocyanins: Interactions with Dietary Fat Levels in the C57BL/6J Mouse Model of Obesity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhena, R.; Figueiredo, I.; Baviera, A.; Silva, D.; Marson, B.; Oliveira, J.; Peccinini, R.; Borges, I.; Pontarolo, R. Antidiabetic activity of Musa x paradisiaca extracts in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and chemical characterization by HPLC-DAD-MS. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 254, 112666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremonini, E.; Daveri, E.; Iglesias, D.E.; Kang, J.; Wang, Z.; Gray, R.; Mastaloudis, A.; Kay, C.D.; Hester, S.N.; Wood, S.M.; et al. A randomized placebo-controlled cross-over study on the effects of anthocyanins on inflammatory and metabolic responses to a high-fat meal in healthy subjects. Redox Biol. 2022, 51, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W.; Foote, K.; Fillmore, S.A.E.; Lyon, M.; Van Lunen, T.A.; McRae, K.B. Effect of blueberry feeding on plasma lipids in pigs. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.; Hoffman, J.; Martinez, K.; Grace, M.; Lila, M.A.; Cockrell, C.; Nadimpalli, A.; Chang, E.; Chuang, C.C.; Zhong, W.; et al. A polyphenol-rich fraction obtained from table grapes decreases adiposity, insulin resistance and markers of inflammation and impacts gut microbiota in high-fat-fed mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 31, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Avila, J.A.; González-Aguilar, G.A.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E.; de la Rosa, L.A. Modulation of PPAR Expression and Activity in Response to Polyphenolic Compounds in High Fat Diets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.-C.; Bae, J.-S. Suppressive effects of pelargonidin on PolyPhosphate-mediated vascular inflammatory responses. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2017, 40, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagioli, M.; Carino, A.; Fiorucci, C.; Annunziato, G.; Marchianò, S.; Bordoni, M.; Roselli, R.; Giorgio, C.D.; Castiglione, F.; Ricci, P.; et al. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) Mediates the Counter-Regulatory Effects of Pelargonidins in Models of Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunctions. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghattamaneni, N.K.R.; Sharma, A.; Panchal, S.K.; Brown, L. Pelargonidin 3-glucoside-enriched strawberry attenuates symptoms of DSS-induced inflammatory bowel disease and diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 2905–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, S.; Rendine, M.; Marino, M.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Riso, P.; Del Bo, C. Differential Effects of Wild Blueberry (Poly)Phenol Metabolites in Modulating Lipid Metabolism and Oxidative Stress in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e70101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E.S.; Lim, J.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Chung, S.; Shin, S.J.; Choi, B.S.; Kim, H.W.; Hwang, S.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Park, C.W.; et al. Anthocyanin-rich Seoritae extract ameliorates renal lipotoxicity via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in diabetic mice. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Balandrano, D.D.; Chai, Z.; Hutabarat, R.P.; Beta, T.; Feng, J.; Ma, K.; Li, D.; Huang, W. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of blueberry anthocyanins by AMPK activation: In vitro and in vivo studies. Redox Biol. 2021, 46, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daveri, E.; Cremonini, E.; Mastaloudis, A.; Hester, S.N.; Wood, S.M.; Waterhouse, A.L.; Anderson, M.; Fraga, C.G.; Oteiza, P.I. Cyanidin and delphinidin modulate inflammation and altered redox signaling improving insulin resistance in high fat-fed mice. Redox Biol. 2018, 18, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Park, Y.J.; Song, M.G.; Kim, D.R.; Zada, S.; Kim, D.H. Cytoprotective Effects of Delphinidin for Human Chondrocytes against Oxidative Stress through Activation of Autophagy. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.D.; Wu, R.; Li, S.; Yang, A.Y.; Kong, A.N. Anthocyanin Delphinidin Prevents Neoplastic Transformation of Mouse Skin JB6 P+ Cells: Epigenetic Re-activation of Nrf2-ARE Pathway. AAPS J. 2019, 21, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, G.; Yang, R.; Chen, J.; Xiang, X.; Qin, H.; Chen, J. Inhibitory Effect of Delphinidin on Oxidative Stress Induced by H(2)O(2) in HepG2 Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 4694760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassellund, S.S.; Flaa, A.; Kjeldsen, S.E.; Seljeflot, I.; Karlsen, A.; Erlund, I.; Rostrup, M. Effects of anthocyanins on cardiovascular risk factors and inflammation in pre-hypertensive men: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled crossover study. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2013, 27, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, R.; Nishimura, N.; Hoshino, H.; Isa, Y.; Kadowaki, M.; Ichi, T.; Tanaka, A.; Nishiumi, S.; Fukuda, I.; Ashida, H.; et al. Cyanidin 3-glucoside ameliorates hyperglycemia and insulin sensitivity due to downregulation of retinol binding protein 4 expression in diabetic mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 74, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Chen, W.; Huang, X.F.; Yan, F.J.; Deng, S.G.; Zheng, X.D.; Shan, P.F. Anti-diabetic effect of anthocyanin cyanidin-3-O-glucoside: Data from insulin resistant hepatocyte and diabetic mouse. Nutr. Diabetes 2024, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay; Shin, J.H.; Park, M.; Lee, H.J. Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside Regulates the M1/M2 Polarization of Microglia via PPARγ and Aβ42 Phagocytosis Through TREM2 in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 5135–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamsamer, C.; Sirivarasai, J.; Sutjarit, N. The Benefits of Anthocyanins against Obesity-Induced Inflammation. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Sun, X. The molecular mechanism of macrophage-adipocyte crosstalk in maintaining energy homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1378202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Shu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, L. AMPK Regulates M1 Macrophage Polarization through the JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway to Attenuate Airway Inflammation in Obesity-Related Asthma. Inflammation 2025, 48, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.M.; Lee, J.H.; Pan, Q.; Han, H.W.; Shen, Z.; Eshghjoo, S.; Wu, C.S.; Yang, W.; Noh, J.Y.; Threadgill, D.W.; et al. Nutrient-sensing growth hormone secretagogue receptor in macrophage programming and meta-inflammation. Mol. Metab. 2024, 79, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]