Association Between Exposure to Age Discrimination and Nutritional Risk: Findings from a Nationwide Sample of Older Adults in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Age Discrimination

2.3. Nutritional Risk

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analyses

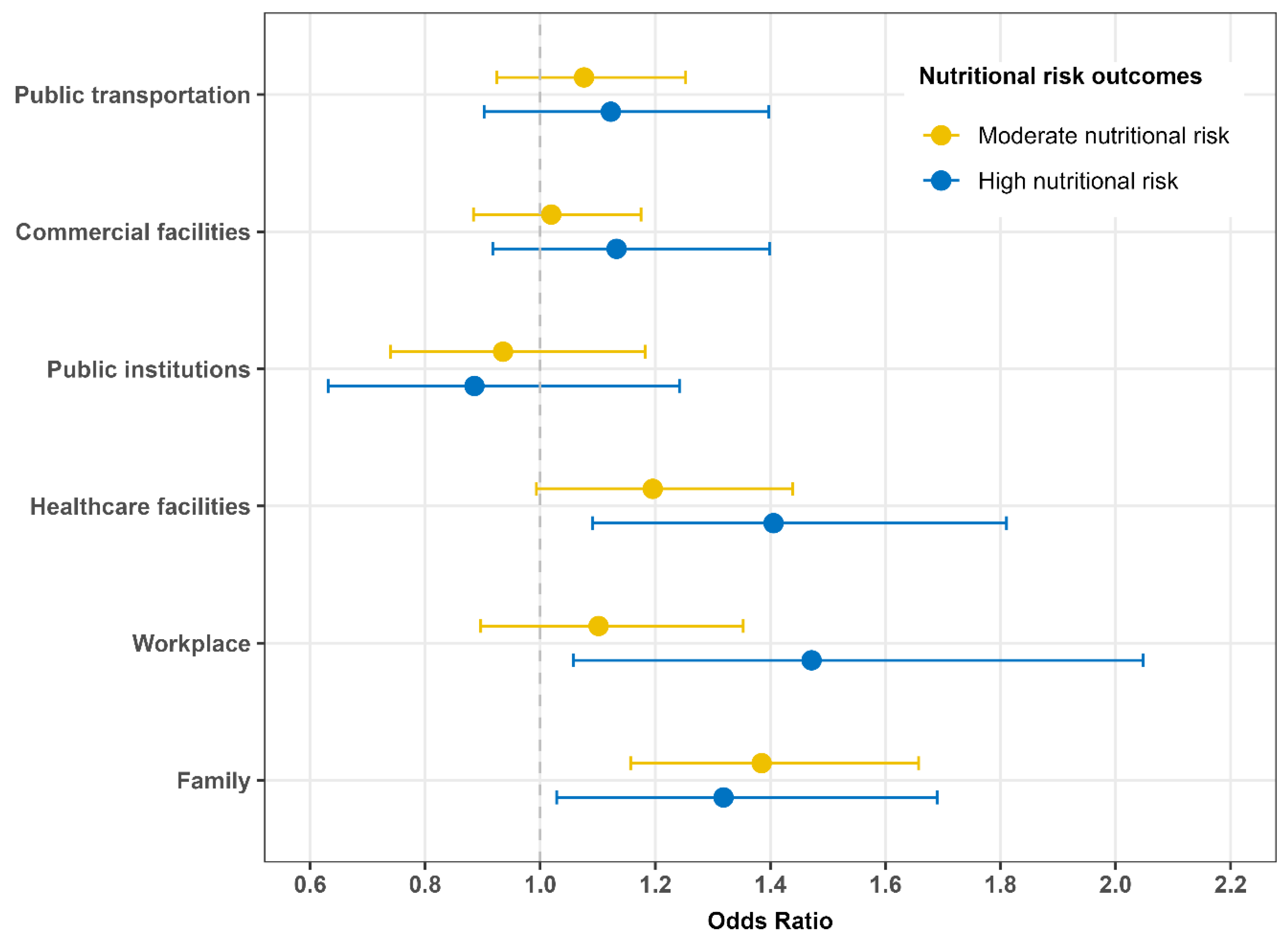

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iversen, T.N.; Larsen, L.; Solem, P.E. A conceptual analysis of Ageism. Nord. Psychol. 2009, 61, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Roy, S. Combatting ageism in the Western Pacific region. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2023, 35, 100593. [Google Scholar]

- Mikton, C.; de la Fuente-Nunez, V.; Officer, A.; Krug, E. Ageism: A social determinant of health that has come of age. Lancet 2021, 397, 1333–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Report on Ageism. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240016866 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Rudnicka, E.; Napierala, P.; Podfigurna, A.; Meczekalski, B.; Smolarczyk, R.; Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas 2020, 139, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Coundouris, S.P.; Nangle, M.R. Breaking the links between ageism and health: An integrated perspective. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 95, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.E.; Hackett, R.A.; Steptoe, A. Associations between age discrimination and health and wellbeing: Cross-sectional and prospective analysis of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e200–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminu, A.Q.; Torrance, N.; Grant, A.; Kydd, A. Is age discrimination a risk factor for frailty progression and frailty development among older adults? A prospective cohort analysis of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 118, 105282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Ihara, E.S. Age discrimination and depression among older adults in South Korea: Moderating effects of exercise. Aging Health Res. 2025, 5, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.; Han, S.Y.; Jang, H.Y. Factors Influencing Suicidal Ideation and Attempts among Older Korean Adults: Focusing on Age Discrimination and Neglect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1852. [Google Scholar]

- Kydd, A.; Fleming, A. Ageism and age discrimination in health care: Fact or fiction? A narrative review of the literature. Maturitas 2015, 81, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, K.; Kim, Y.; Woo, S.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, I.; Song, J.; Lee, S.J.; Min, J. The impact of long working hours on daily sodium intake. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024, 36, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Ju, K.; Kim, J.; Song, J.; Lee, S.J.; Min, J. Differences of nutritional intake habits and Dietary Inflammatory Index score between occupational classifications in the Korean working population. Ann. Occup Environ. Med. 2024, 36, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayal, D. Gender inequality, reproductive rights and food insecurity in Sub-Saharan Africa—A panel data study. Int. J. Dev. Issues 2019, 18, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, K.J.; Larranaga, D.; Jabson Tree, J.M. Discrimination and microaggressions as mediators of food insecurity among transgender college students. J. Am. Coll Health 2025, 73, 2054–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, Y.E.; Fanton, M.; Novossat, R.S.; Canuto, R. Perceived racial discrimination and eating habits: A systematic review and conceptual models. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1769–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, K.A.; Shrivastava, S. Discrimination as social exclusion. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2024, 82, 476–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odumegwu, J.N.; Bather, J.R.; Cuevas, A.G.; Rhodes-Bratton, B.; Goodman, M.S. Perceived racial discrimination over the life course and financial stress. Discov. Soc. Sci. Health 2025, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Kilpatrick, L.A.; Dong, T.S.; Gee, G.C.; Labus, J.S.; Osadchiy, V.; Beltran-Sanchez, H.; Wang, M.C.; Vaughan, A.; et al. Discrimination exposure impacts unhealthy processing of food cues: Crosstalk between the brain and gut. Nat. Ment. Health 2023, 1, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M. Prediction model for identifying a high-risk group for food insecurity among elderly South Koreans. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, B.M.; Jette, A.M.; Smith, K.W.; Miller, D.R. Nutrition and health risks in the elderly: The nutrition screening initiative. Am. J. Public Health 1993, 83, 972–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.-K.; Kong, J.E. Reliability of Nutritional Screening Using DETERMINE Checklist for Elderly in Korean Rural Areas by Season. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2009, 14, 340–353. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.S.; Lee, J. Nutrients intake, zinc status and health risk factors in elderly Korean women as evaluated by the Nutrition Screening Inistiative (NSI) checklist. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2002, 7, 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, S.; Cho, S.S.; Kim, J.I.; Ryu, H.; Kim, H. Association between discrimination in the workplace and insomnia symptoms. Ann Occup Environ. Med. 2023, 35, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santha, A.; Tóth-Batizán, E.E. Age Discrimination of Senior Citizens in European Countries. Societies 2024, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, R.; Toosi, N.; Wood, L.; Correia, A.; Medina, N.; Pritchard, M.; Venerable, J.; Lee, M.; Santillan, J.K.A. Racial discrimination is associated with food insecurity, stress, and worse physical health among college students. BMC Public Health 2024, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Yesildemir, O.; Akbulut, G. Gender-Affirming Nutrition: An Overview of Eating Disorders in the Transgender Population. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.J.; Veale, J.F.; Saewyc, E.M. Disordered eating behaviors among transgender youth: Probability profiles from risk and protective factors. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 50, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Rojas, D.M.; Velasquez-Huaman, P.F.; Hernandez-Vasquez, A.; Azanedo, D. Perception of discrimination by the head of the household and household food insecurity in Venezuelan migrants in Peru: Cross-sectional analysis of a population-based survey. Prev. Med. Rep. 2025, 53, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Cohn-Schwartz, E. The Relationship Between Perceived Age Discrimination in the Healthcare System and Health: An Examination of a Multi-Path Model in a National Sample of Israelis Over the Age of 50. J. Aging Health 2021, 34, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; Scharf, T.; Keating, N. Social exclusion of older persons: A scoping review and conceptual framework. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teran-Mendoza, O.; Cancino, V. Ageism and Loneliness in People Over 50: Understanding the Role of Self-Perception of Aging and Social Isolation in a Chilean Sample. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2025, 44, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Lee, D.W.; Kang, M.Y. Exploring the impact of age and socioeconomic factors on health-related unemployment using propensity score matching: Results from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2015–2017). Ann. Occup Environ. Med. 2024, 36, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, R.; Reid, K. Supporting each other: Older adults’ experiences empowering food security and social inclusion in rural and food desert communities. Appetite 2024, 198, 107353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locher, J.L.; Ritchie, C.S.; Roth, D.L.; Baker, P.S.; Bodner, E.V.; Allman, R.M. Social isolation, support, and capital and nutritional risk in an older sample: Ethnic and gender differences. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, K.; Cross, J.; Nicholls, A.; Gallegos, D. The association between loneliness or social isolation and food and eating behaviours: A scoping review. Appetite 2023, 191, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, U.S.; Miller, E.R.; Hegde, R.R. Experiences of Discrimination Are Associated With Greater Resting Amygdala Activity and Functional Connectivity. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.; Liu, S.; Heim, C.; Heinz, A. The effects of social isolation stress and discrimination on mental health. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengton, R.; Schoenmakers, M.; Penninx, B.; Boon, M.R.; van Rossum, E.F.C. Glucocorticoids and HPA axis regulation in the stress-obesity connection: A comprehensive overview of biological, physiological and behavioural dimensions. Clin. Obes. 2025, 15, e12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, V. From telomeres and senescence to integrated longevity medicine: Redefining the path to extended healthspan. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, N.; Biro, E.; Piko, P.; Ungvari, Z.; Adany, R. Attitudes towards healthy eating and its determinants among older adults in a deprived region of Hungary: Implications for the National Healthy Aging Program. Geroscience 2025, 47, 5695–5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamzadeh, S.; Shaygan, M.; Naderi, Z.; Hosseini, F.A. Age discrimination perceived by hospitalized older adult patients in Iran: A qualitative study. Health Promot. Perspect. 2022, 12, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, I.H.; Cho, L.-J. Confucianism and the Korean family. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 1995, 26, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark, D. Strengthen Age Discrimination Protections to Help Confront the Challenge of Population Aging. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2022, 34, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braude, P.; Lewis, E.G.; Broach Kc, S.; Carlton, E.; Rudd, S.; Palmer, J.; Walker, R.; Carter, B.; Benger, J. Frailism: A scoping review exploring discrimination against people living with frailty. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2025, 6, 100651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall | Dimensions of Age Discrimination Experienced | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | One | Two | Three or More | ||

| n = 9951 | n = 7333 | n = 1537 | n = 598 | n = 483 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 3824 (38.4%) | 2807 (38.3%) | 583 (37.9%) | 238 (39.8%) | 196 (40.6%) |

| Female | 6127 (61.6%) | 4526 (61.7%) | 954 (62.1%) | 360 (60.2%) | 287 (59.4%) |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 74.0 (6.8) | 74.2 (6.7) | 73.6 (6.7) | 73.7 (6.8) | 73.6 (7.1) |

| Educational level | |||||

| No education | 1435 (14.4%) | 1088 (14.8%) | 208 (13.5%) | 76 (12.7%) | 63 (13.0%) |

| Elementary school | 2920 (29.3%) | 2212 (30.2%) | 412 (26.8%) | 175 (29.3%) | 121 (25.1%) |

| Middle school | 2114 (21.2%) | 1562 (21.3%) | 332 (21.6%) | 133 (22.2%) | 87 (18.0%) |

| High school | 2860 (28.7%) | 1977 (27.0%) | 515 (33.5%) | 185 (30.9%) | 183 (37.9%) |

| College or higher | 622 (6.3%) | 494 (6.7%) | 70 (4.6%) | 29 (4.8%) | 29 (6.0%) |

| Income level | |||||

| Lowest | 2107 (21.2%) | 1699 (23.2%) | 250 (16.3%) | 83 (13.9%) | 75 (15.5%) |

| Low | 2167 (21.8%) | 1645 (22.4%) | 321 (20.9%) | 116 (19.4%) | 85 (17.6%) |

| Medium | 2026 (20.4%) | 1467 (20.0%) | 335 (21.8%) | 119 (19.9%) | 105 (21.7%) |

| High | 1910 (19.2%) | 1384 (18.9%) | 317 (20.6%) | 121 (20.2%) | 88 (18.2%) |

| Highest | 1741 (17.5%) | 1138 (15.5%) | 314 (20.4%) | 159 (26.6%) | 130 (26.9%) |

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed | 3942 (39.6%) | 2846 (38.8%) | 634 (41.2%) | 257 (43.0%) | 205 (42.4%) |

| Unemployed | 6009 (60.4%) | 4487 (61.2%) | 903 (58.8%) | 341 (57.0%) | 278 (57.6%) |

| Functional limitation | |||||

| Yes | 1648 (16.6%) | 1087 (14.8%) | 308 (20.0%) | 125 (20.9%) | 128 (26.5%) |

| No | 8303 (83.4%) | 6246 (85.2%) | 1229 (80.0%) | 473 (79.1%) | 355 (73.5%) |

| Depressive symptoms | |||||

| Yes | 7893 (79.3%) | 6021 (82.1%) | 1149 (74.8%) | 422 (70.6%) | 301 (62.3%) |

| No | 2058 (20.7%) | 1312 (17.9%) | 388 (25.2%) | 176 (29.4%) | 182 (37.7%) |

| K-MMSE~2 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 24.5 (4.8) | 24.8 (4.4) | 23.6 (5.8) | 23.7 (5.2) | 23.6 (5.0) |

| Body mass index | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 23.6 (2.6) | 23.7 (2.7) | 23.6 (2.5) | 23.4 (2.5) | 23.7 (2.5) |

| Nutritional risk | |||||

| Low risk | 4243 (42.6%) | 3266 (44.5%) | 602 (39.2%) | 220 (36.8%) | 155 (32.1%) |

| Moderate risk | 4463 (44.8%) | 3253 (44.4%) | 706 (45.9%) | 279 (46.7%) | 225 (46.6%) |

| High risk | 1245 (12.5%) | 814 (11.1%) | 229 (14.9%) | 99 (16.6%) | 103 (21.3%) |

| Unadjusted Model | Fully Adjusted Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Risk Outcomes | Nutritional Risk Outcomes | |||

| Moderate Risk | High Risk | Moderate Risk | High Risk | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age discrimination | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| One dimension | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | 1.50 (1.28–1.77) | 1.17 (1.04–1.32) | 1.40 (1.17–1.69) |

| Two dimensions | 1.16 (0.98–1.38) | 1.79 (1.43–2.25) | 1.20 (1.00–1.43) | 1.46 (1.13–1.89) |

| Three or more dimensions | 1.51 (1.25–1.82) | 2.67 (2.11–3.39) | 1.53 (1.25–1.88) | 1.89 (1.44–2.48) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, S.-U.; Yoon, J.-H. Association Between Exposure to Age Discrimination and Nutritional Risk: Findings from a Nationwide Sample of Older Adults in South Korea. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3643. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233643

Baek S-U, Yoon J-H. Association Between Exposure to Age Discrimination and Nutritional Risk: Findings from a Nationwide Sample of Older Adults in South Korea. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3643. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233643

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Seong-Uk, and Jin-Ha Yoon. 2025. "Association Between Exposure to Age Discrimination and Nutritional Risk: Findings from a Nationwide Sample of Older Adults in South Korea" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3643. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233643

APA StyleBaek, S.-U., & Yoon, J.-H. (2025). Association Between Exposure to Age Discrimination and Nutritional Risk: Findings from a Nationwide Sample of Older Adults in South Korea. Nutrients, 17(23), 3643. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233643