Guide for Selecting Experimental Models to Study Dietary Fat Absorption

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

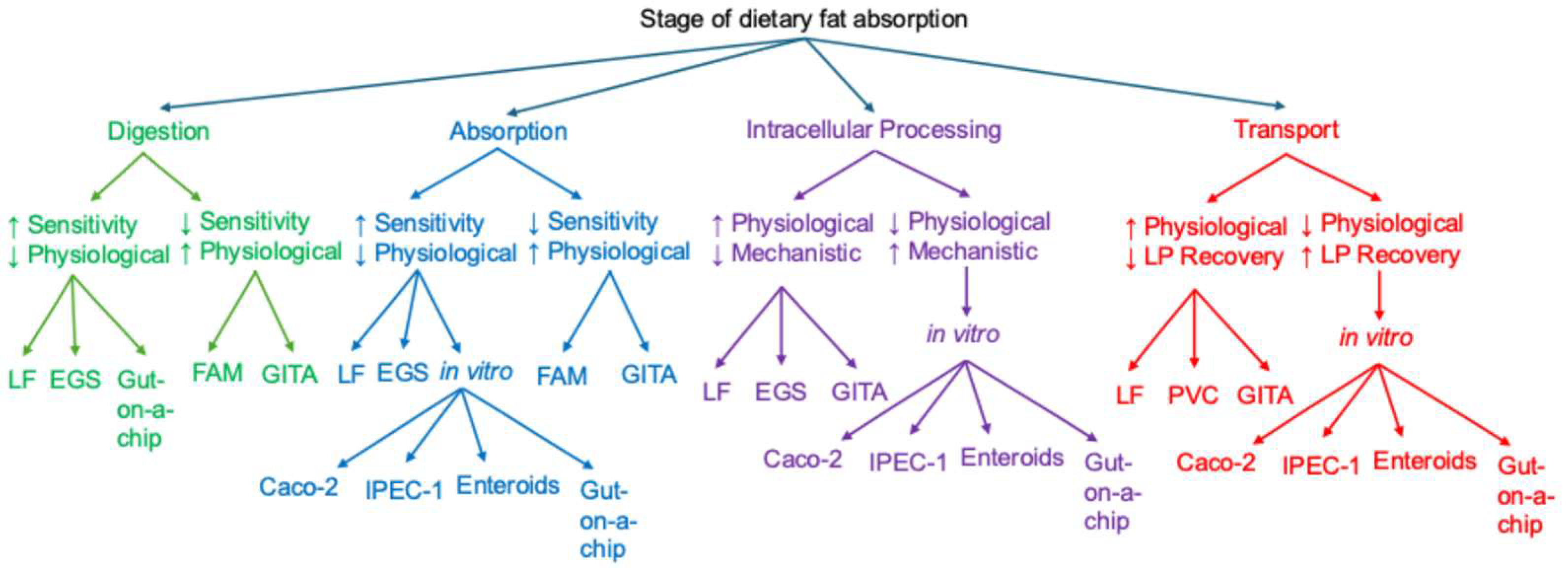

3. Experimental Models

- In vivo, which best replicate physiological conditions

- Ex vivo, which enable controlled studies of intact intestinal segments

- In vitro, which offer high experimental control for mechanistic studies

3.1. In Vivo Models

3.1.1. Lymph Duct Cannulation

3.1.2. Portal Vein Cannulation

3.1.3. Isotope Labeling

3.1.4. Fecal Analysis

3.1.5. Analysis of Peripheral Blood

3.1.6. Analysis of Intestinal Tissues

3.1.7. The Utility of Pharmacological Agents

3.2. Ex Vivo Models

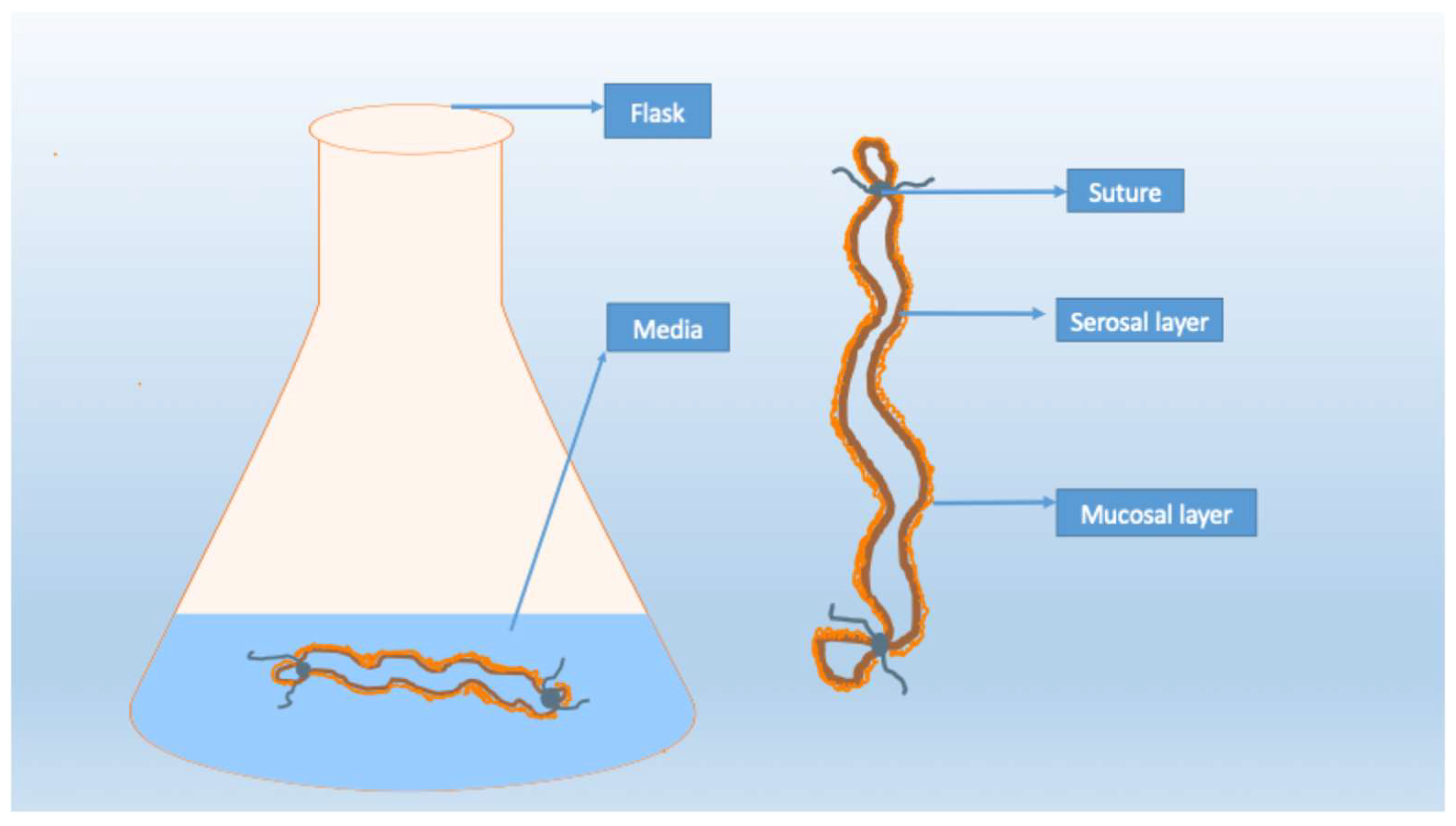

3.2.1. Everted Gut Sac

3.2.2. Human Fetal Gut

3.3. In Vitro Models

3.3.1. Caco-2 Cells

3.3.2. IPEC-1 Cells

3.3.3. Enteroids

3.3.4. Gut-on-a-Chip

4. Integration of Experimental Models

4.1. In Vivo Models: Unmatched Physiological Relevance, Limited Mechanistic Resolution

4.1.1. Transport Between Lymphatic and Portal Route

4.1.2. Digestion and Absorption

4.2. Ex Vivo Models: Preserved Tissue Structure with Limited Functional Scope

4.3. In Vitro Models: Highest Mechanistic Resolution, Lowest Physiological Relevance

4.4. Future Directions: Integrating Systems to Bridge Physiological and Mechanistic Gaps

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Caco-2 | Cancer Coli-2 |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| IPEC-1 | intestinal porcine epithelial cells |

| VEGF-A | vascular endothelia growth factor A |

| VLDL | very low-density lipoprotein |

References

- Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Pan, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, Y. New insights into the role of dietary triglyceride absorption in obesity and metabolic diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1097835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, P.; Nauli, A.; Lo, C.M. Enterocyte fatty acid uptake and intestinal fatty acid-binding protein. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2004, 32, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauli, A.M.; Nauli, S.M. Intestinal transport as a potential determinant of drug bioavailability. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 8, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, N.; Simionescu, M.; Palade, G.E. Permeability of intestinal capillaries. Pathway followed by dextrans and glycogens. J. Cell Biol. 1972, 53, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauli, A.M.; Matin, S. Why Do Men Accumulate Abdominal Visceral Fat? Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Daniels, S.R.; Donato, K.A.; Eckel, R.H.; Franklin, B.A.; Gordon, D.J.; Krauss, R.M.; Savage, P.J.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005, 112, 2735–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Shen, L.; Yang, Q.; Nauli, A.M.; Bingamon, M.; Wang, D.Q.; Ulrich-Lai, Y.M.; Tso, P. Sexual dimorphism in intestinal absorption and lymphatic transport of dietary lipids. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 5015–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauli, A.M.; Phan, A.; Tso, P.; Nauli, S.M. The effects of sex hormones on the size of intestinal lipoproteins. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1316982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansbach, C.M., 2nd; Dowell, R.F. Portal transport of long acyl chain lipids: Effect of phosphatidylcholine and low infusion rates. Am. J. Physiol. 1993, 264, G1082–G1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansbach, C.M., II; Dowell, R.F.; Pritchett, D. Portal transport of absorbed lipids in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1991, 261, G530–G538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahara, E.; Mantani, Y.; Udayanga, K.G.; Qi, W.M.; Tanida, T.; Takeuchi, T.; Yokoyama, T.; Hoshi, N.; Kitagawa, H. Ultrastructural demonstration of the absorption and transportation of minute chylomicrons by subepithelial blood capillaries in rat jejunal villi. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2013, 75, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, N.; Proulx, S.T.; Karaman, S.; Dillard, M.E.; Johnson, N.; Detmar, M.; Oliver, G. Restoration of lymphatic function rescues obesity in Prox1-haploinsufficient mice. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e85096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.L.; Srinivasan, R.S.; Dillard, M.E.; Johnson, N.C.; Witte, M.H.; Boyd, K.; Sleeman, M.W.; Oliver, G. Lymphatic vascular defects promoted by Prox1 haploinsufficiency cause adult-onset obesity. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Qiu, X.; Ma, H.; Geng, Q. Incidence and long-term specific mortality trends of metabolic syndrome in the United States. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1029736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuvarox, T.; Goosenberg, E.; Belletieri, C. Malabsorption Syndromes. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, E.; Beaulieu, J.F.; Spahis, S. From Congenital Disorders of Fat Malabsorption to Understanding Intra-Enterocyte Mechanisms Behind Chylomicron Assembly and Secretion. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 629222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwich, A.S.; Aslam, U.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A. Meta-analysis of the turnover of intestinal epithelia in preclinical animal species and humans. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014, 42, 2016–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutton, J.S.; Hinman, S.S.; Kim, R.; Wang, Y.; Allbritton, N.L. Primary Cell-Derived Intestinal Models: Recapitulating Physiology. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 744–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Votruba, S.B.; Jensen, M.D. Sex-specific differences in leg fat uptake are revealed with a high-fat meal. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 291, E1115–E1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votruba, S.B.; Mattison, R.S.; Dumesic, D.A.; Koutsari, C.; Jensen, M.D. Meal fatty acid uptake in visceral fat in women. Diabetes 2007, 56, 2589–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.M.; Nordskog, B.K.; Nauli, A.M.; Zheng, S.; Vonlehmden, S.B.; Yang, Q.; Lee, D.; Swift, L.L.; Davidson, N.O.; Tso, P. Why does the gut choose apolipoprotein B48 but not B100 for chylomicron formation? Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 294, G344–G352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauli, A.M.; Nassir, F.; Zheng, S.; Yang, Q.; Lo, C.M.; Vonlehmden, S.B.; Lee, D.; Jandacek, R.J.; Abumrad, N.A.; Tso, P. CD36 is important for chylomicron formation and secretion and may mediate cholesterol uptake in the proximal intestine. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, J.B.; Jorgensen, H.; Mu, H. Diacylglycerol oil does not affect portal vein transport of nonesterified fatty acids but decreases the postprandial plasma lipid response in catheterized pigs. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1800–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, M.A.; Diane, A.; Singh, V.P.; Mangat, R.; Krysa, J.A.; Nelson, R.; Willing, B.P.; Proctor, S.D. Low birth weight causes insulin resistance and aberrant intestinal lipid metabolism independent of microbiota abundance in Landrace-Large White pigs. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 9250–9262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peachey, S.E.; Dawson, J.M.; Harper, E.J. The effect of ageing on nutrient digestibility by cats fed beef tallow-, sunflower oil- or olive oil-enriched diets. Growth Dev. Aging 1999, 63, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jensen, G.L.; McGarvey, N.; Taraszewski, R.; Wixson, S.K.; Seidner, D.L.; Pai, T.; Yeh, Y.Y.; Lee, T.W.; DeMichele, S.J. Lymphatic absorption of enterally fed structured triacylglycerol vs physical mix in a canine model. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 60, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, J.S.; Crouse, J.R. Reduction of cholesterol absorption by dietary oleinate and fish oil in African green monkeys. J. Lipid Res. 1992, 33, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magubane, M.M.; Lembede, B.W.; Erlwanger, K.H.; Chivandi, E.; Donaldson, J. Fat absorption and deposition in Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) fed a high fat diet. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2013, 84, E1–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Semova, I.; Carten, J.D.; Stombaugh, J.; Mackey, L.C.; Knight, R.; Farber, S.A.; Rawls, J.F. Microbiota regulate intestinal absorption and metabolism of fatty acids in the zebrafish. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, T.O.C.; Farber, S.A. Zebrafish ApoB-Containing Lipoprotein Metabolism: A Closer Look. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.C.; Coschigano, K.T. ApoB48 as an Efficient Regulator of Intestinal Lipid Transport. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollman, J.L.; Cain, J.C.; Grindlay, J.H. Techniques for the collection of lymph from the liver, small intestine, or thoracic duct of the rat. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1948, 33, 1349–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, C.J.; Charman, W.N. Model systems for intestinal lymphatic transport studies. Pharm. Biotechnol. 1996, 8, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, P.; Simmonds, W.J. The absorption of lipid and lipoprotein synthesis. Lab. Res. Methods Biol. Med. 1984, 10, 191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, C.W.; Qu, J.; Liu, M.; Black, D.D.; Tso, P. Use of Isotope Tracers to Assess Lipid Absorption in Conscious Lymph Fistula Mice. Curr. Protoc. Mouse Biol. 2019, 9, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedousis, N.; Teng, L.; Kanshana, J.S.; Kohan, A.B. A single-day mouse mesenteric lymph surgery in mice: An updated approach to study dietary lipid absorption, chylomicron secretion, and lymphocyte dynamics. J. Lipid Res. 2022, 63, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedousis, N.L.; Teng, L.; Kohan, A.B. The Isolation of Flowing Mesenteric Lymph in Mice to Quantify In Vivo Kinetics of Dietary Lipid Absorption and Chylomicron Secretion. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 189, e64338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansbach, C.M., 2nd; Arnold, A. Steady-state kinetic analysis of triacylglycerol delivery into mesenteric lymph. Am. J. Physiol. 1986, 251, G263–G269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drover, V.A.; Ajmal, M.; Nassir, F.; Davidson, N.O.; Nauli, A.M.; Sahoo, D.; Tso, P.; Abumrad, N.A. CD36 deficiency impairs intestinal lipid secretion and clearance of chylomicrons from the blood. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoving, J.; Wilson, J.H.; Valkema, A.J.; Woldring, M.G. Estimation of fat absorption from single fecal specimens using 131I-triolein and 75Se-triether. A study in rats with and without induced steatorrhea. Gastroenterology 1977, 72, 406–412. [Google Scholar]

- Jandacek, R.J.; Heubi, J.E.; Tso, P. A novel, noninvasive method for the measurement of intestinal fat absorption. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, C.; Ikeda, S.; Uchida, T.; Yamashita, K.; Ichikawa, T. Triton WR1339, an inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase, decreases vitamin E concentration in some tissues of rats by inhibiting its transport to liver. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blom, D.J.; Marais, A.D.; Raal, F.J. Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia Treatment: New Developments. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2025, 27, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrick, T.W.; Camilleri, M.; Acosta, A. Pharmacotherapy for Obesity: Recent Updates. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 17, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, T.H.; Wiseman, G. The use of sacs of everted small intestine for the study of the transference of substances from the mucosal to the serosal surface. J. Physiol. 1954, 123, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Al-Jenoobi, F.I.; Al-Mohizea, A.M. Everted gut sac model as a tool in pharmaceutical research: Limitations and applications. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, B.E. Insights into digestion and absorption of major nutrients in humans. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2010, 34, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiela, P.R.; Ghishan, F.K. Physiology of Intestinal Absorption and Secretion. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelberg, H.B. Comparative anatomy, physiology, and mechanisms of disease production of the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. Toxicol. Pathol. 2014, 42, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, E.W. Electron microscopic study of intestinal fat absorption in vitro from mixed micelles containing linolenic acid, monoolein, and bile salt. J. Lipid Res. 1966, 7, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, E.W. Effects of calcium and magnesium ions upon fat absorption by sacs of everted hamster intestine. Gastroenterology 1977, 73, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.L.; Lanz, H.C.; Senior, J.R. Bile salt regulation of fatty acid absorption and esterification in rat everted jejunal sacs in vitro and into thoracic duct lymph in vivo. J. Clin. Investig. 1969, 48, 1587–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampone, A.J. The effects of bile salt and raw bile on the intestinal absorption of micellar fatty acid in the rat in vitro. J. Physiol. 1972, 222, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampone, A.J. The effect of lecithin on intestinal cholesterol uptake by rat intestine in vitro. J. Physiol. 1973, 229, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, J.B.; O’Connor, P.J. Effect of phosphatidylcholine on fatty acid and cholesterol absorption from mixed micellar solutions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1975, 409, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noben, M.; Vanhove, W.; Arnauts, K.; Santo Ramalho, A.; Van Assche, G.; Vermeire, S.; Verfaillie, C.; Ferrante, M. Human intestinal epithelium in a dish: Current models for research into gastrointestinal pathophysiology. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2017, 5, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R.J.; Koldovsky, O.; Hoskova, J.; Jirsova, V.; Uher, J. Electrical activity across human foetal small intestine associated with absorption processes. Gut 1968, 9, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yissachar, N.; Zhou, Y.; Ung, L.; Lai, N.Y.; Mohan, J.F.; Ehrlicher, A.; Weitz, D.A.; Kasper, D.L.; Chiu, I.M.; Mathis, D.; et al. An Intestinal Organ Culture System Uncovers a Role for the Nervous System in Microbe-Immune Crosstalk. Cell 2017, 168, 1135–1148.e1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, E.; Thibault, L.; Delvin, E.; Menard, D. Apolipoprotein synthesis in human fetal intestine: Regulation by epidermal growth factor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 204, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, E.; Stan, S.; Garofalo, C.; Delvin, E.E.; Seidman, E.G.; Menard, D. Immunolocalization, ontogeny, and regulation of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in human fetal intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2001, 280, G563–G571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loirdighi, N.; Menard, D.; Levy, E. Insulin decreases chylomicron production in human fetal small intestine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1992, 1175, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantret, I.; Barbat, A.; Dussaulx, E.; Brattain, M.G.; Zweibaum, A. Epithelial polarity, villin expression, and enterocytic differentiation of cultured human colon carcinoma cells: A survey of twenty cell lines. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 1936–1942. [Google Scholar]

- Nauli, A.M.; Zheng, S.; Yang, Q.; Li, R.; Jandacek, R.; Tso, P. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase release is not associated with chylomicron formation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003, 284, G583–G587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traber, M.G.; Kayden, H.J.; Rindler, M.J. Polarized secretion of newly synthesized lipoproteins by the Caco-2 human intestinal cell line. J. Lipid Res. 1987, 28, 1350–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Greevenbroek, M.M.; van Meer, G.; Erkelens, D.W.; de Bruin, T.W. Effects of saturated, mono-, and polyunsaturated fatty acids on the secretion of apo B containing lipoproteins by Caco-2 cells. Atherosclerosis 1996, 121, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, E.; Yotov, W.; Seidman, E.G.; Garofalo, C.; Delvin, E.; Menard, D. Caco-2 cells and human fetal colon: A comparative analysis of their lipid transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1439, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchoomun, J.; Hussain, M.M. Assembly and secretion of chylomicrons by differentiated Caco-2 cells. Nascent triglycerides and preformed phospholipids are preferentially used for lipoprotein assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 19565–19572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauli, A.M.; Sun, Y.; Whittimore, J.D.; Atyia, S.; Krishnaswamy, G.; Nauli, S.M. Chylomicrons produced by Caco-2 cells contained ApoB-48 with diameter of 80–200 nm. Physiol. Rep. 2014, 2, e12018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauli, A.M.; Whittimore, J.D. Using Caco-2 Cells to Study Lipid Transport by the Intestine. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 102, e53086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theile, D.; Staffen, B.; Weiss, J. ATP-binding cassette transporters as pitfalls in selection of transgenic cells. Anal. Biochem. 2010, 399, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Vallina, R.; Wang, H.; Zhan, R.; Berschneider, H.M.; Lee, R.M.; Davidson, N.O.; Black, D.D. Lipoprotein and apolipoprotein secretion by a newborn piglet intestinal cell line (IPEC-1). Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 271, G249–G259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Yao, Y.; Cheng, X.; Mitchell, S.; Leng, S.; Meng, S.; Gallagher, J.W.; Shelness, G.S.; Morris, G.S.; Mahan, J.; et al. Overexpression of apolipoprotein A-IV enhances lipid secretion in IPEC-1 cells by increasing chylomicron size. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 3473–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Yao, Y.; Meng, S.; Cheng, X.; Black, D.D. Overexpression of apolipoprotein A-IV enhances lipid transport in newborn swine intestinal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 31929–31937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Lu, S.; Huang, Y.; Beeman-Black, C.C.; Lu, R.; Pan, X.; Hussain, M.M.; Black, D.D. Regulation of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein by apolipoprotein A-IV in newborn swine intestinal epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011, 300, G357–G363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, K.; Blutt, S.E.; Ettayebi, K.; Zeng, X.L.; Broughman, J.R.; Crawford, S.E.; Karandikar, U.C.; Sastri, N.P.; Conner, M.E.; Opekun, A.R.; et al. Human Intestinal Enteroids: A New Model To Study Human Rotavirus Infection, Host Restriction, and Pathophysiology. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Dong, H.; Kohan, A.B. The Isolation, Culture, and Propagation of Murine Intestinal Enteroids for the Study of Dietary Lipid Metabolism. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1576, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jattan, J.; Rodia, C.; Li, D.; Diakhate, A.; Dong, H.; Bataille, A.; Shroyer, N.F.; Kohan, A.B. Using primary murine intestinal enteroids to study dietary TAG absorption, lipoprotein synthesis, and the role of apoC-III in the intestine. J. Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, G.; Rodia, C.; Li, D.; Johnson, Z.; Dong, H.; Kohan, A.B. Key differences between apoC-III regulation and expression in intestine and liver. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 491, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bein, A.; Shin, W.; Jalili-Firoozinezhad, S.; Park, M.H.; Sontheimer-Phelps, A.; Tovaglieri, A.; Chalkiadaki, A.; Kim, H.J.; Ingber, D.E. Microfluidic Organ-on-a-Chip Models of Human Intestine. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 5, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, R.; Kim, H. Characterization of a microfluidic in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier (muBBB). Lab Chip 2012, 12, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauke, N.; Smith, G.; Cooper, J.M. Microfluidic systems to examine intercellular coupling of pairs of cardiac myocytes. Lab Chip 2007, 7, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martewicz, S.; Michielin, F.; Serena, E.; Zambon, A.; Mongillo, M.; Elvassore, N. Reversible alteration of calcium dynamics in cardiomyocytes during acute hypoxia transient in a microfluidic platform. Integr. Biol. 2012, 4, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Barrile, R.; van der Meer, A.D.; Mammoto, A.; Mammoto, T.; De Ceunynck, K.; Aisiku, O.; Otieno, M.A.; Louden, C.S.; Hamilton, G.A.; et al. Primary Human Lung Alveolus-on-a-chip Model of Intravascular Thrombosis for Assessment of Therapeutics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 103, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, D.; Leslie, D.C.; Matthews, B.D.; Fraser, J.P.; Jurek, S.; Hamilton, G.A.; Thorneloe, K.S.; McAlexander, M.A.; Ingber, D.E. A human disease model of drug toxicity-induced pulmonary edema in a lung-on-a-chip microdevice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 159ra147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S. Kidney-on-a-Chip: A New Technology for Predicting Drug Efficacy, Interactions, and Drug-induced Nephrotoxicity. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torisawa, Y.S.; Spina, C.S.; Mammoto, T.; Mammoto, A.; Weaver, J.C.; Tat, T.; Collins, J.J.; Ingber, D.E. Bone marrow-on-a-chip replicates hematopoietic niche physiology in vitro. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon No, D.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.H. 3D liver models on a microplatform: Well-defined culture, engineering of liver tissue and liver-on-a-chip. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 3822–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodkowic, D.; Cooper, J.M. Tumors on chips: Oncology meets microfluidics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Midwoud, P.M.; Merema, M.T.; Verpoorte, E.; Groothuis, G.M. A microfluidic approach for in vitro assessment of interorgan interactions in drug metabolism using intestinal and liver slices. Lab Chip 2010, 10, 2778–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasendra, M.; Tovaglieri, A.; Sontheimer-Phelps, A.; Jalili-Firoozinezhad, S.; Bein, A.; Chalkiadaki, A.; Scholl, W.; Zhang, C.; Rickner, H.; Richmond, C.A.; et al. Development of a primary human Small Intestine-on-a-Chip using biopsy-derived organoids. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, P.; Ianovska, M.A.; Mathwig, K.; van Lieshout, G.A.A.; Triantis, V.; Bouwmeester, H.; Verpoorte, E. Digestion-on-a-chip: A continuous-flow modular microsystem recreating enzymatic digestion in the gastrointestinal tract. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeres, G.; Bogicevic, B.; Buri, C.; Carrara, S.; Chollet, M.; Corbino-Giunta, L.; Egger, L.; Gille, D.; Kopf-Bolanz, K.; Laederach, K.; et al. The NutriChip project--translating technology into nutritional knowledge. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wan, L.; Li, T.; Yao, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J. Linoelaidic acid gavage has more severe consequences on triglycerides accumulation, inflammation and intestinal microbiota in mice than elaidic acid. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Analysis | Purpose | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal matter | Measurement of fecal lipid content | Detect fat malabsorption | Provide little information on intestinal lipoprotein transport |

| Lymph | Lipid and apolipoprotein quantification (VLDL, chylomicron, or total fractions); electron microscopy | Analyze intestinal lipoprotein transport and particle size | Smaller intestinal VLDLs may be excluded |

| Peripheral blood | Lipid and apolipoprotein quantification from VLDL and chylomicron fractions | Provide indirect information on intestinal lipoprotein transport | Data affected by metabolic variability; difficult to distinguish intestinal from hepatic VLDLs |

| Portal blood | Lipid and apolipoprotein quantification from VLDL fraction | Assess transport of smaller intestinal VLDLs | Larger intestinal lipoproteins are excluded |

| Intestinal tissues | Microscopy; mRNA and protein expression analyses; mucosal lipid composition profiling | Detect morphological and molecular changes; assess intestinal lipoprotein size and lipid re-esterification | Require complementary data from other sample types to confirm findings |

| Other tissues (e.g., adipose, muscle) | Lipid quantification (often using isotope labeling) | Determine uptake of dietary lipids by peripheral tissues | Provide limited information on intestinal absorption and lipoprotein transport |

| Model/Source | Condition or Treatment | Average Lipoprotein Diameter and Range (nm) | Approximate % VLDLs and % Chylomicrons [References] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 cells | Control (not stimulated with lipid) | 28 (mostly 10–40) | 96% VLDLs and 4% chylomicrons [68] |

| Caco-2 cells | Fatty acid/lecithin/bile salt mixture | 54 (mostly 10–140) | 79% VLDLs and 21% chylomicrons [68] |

| IPEC-1 cells | Fatty acid-albumin complex without ApoA-IV overexpression | 54.3 (mostly 30–80) | 99% VLDLs and 1% chylomicrons [72] |

| IPEC-1 cells | Fatty acid-albumin complex with ApoA-IV overexpression | 87.0 (mostly 30–180) | 47% VLDLs and 53% chylomicrons [72] |

| Enteroids | Control (not stimulated with lipid) | 100 (mostly 50–250) | 38% VLDLs and 62% chylomicrons [77] |

| Enteroids | Fatty acid-albumin complex | 125 (mostly 50–250) | 15% VLDLs and 85% chylomicrons [77] |

| Enteroids | Oleic acid-containing mixed micelles | 110 (mostly 50–175) | 33% VLDLs and 67% chylomicrons [77] |

| Mouse lymph fistula | Preprandial female | 63.16 (mostly 20–140) | 86.58% VLDLs and 13.42% chylomicrons [8] |

| Mouse lymph fistula | Preprandial male | 79.74 (mostly 40–180) | 70.63% VLDLs and 29.37% chylomicrons [8] |

| Mouse lymph fistula | Postprandial female | 83.35 (mostly 20–220) | 69.37% VLDLs and 30.63% chylomicrons [8] |

| Mouse lymph fistula | Postprandial male | 128.41 (mostly 40–260) | 32.54% VLDLs and 67.46% chylomicrons [8] |

| Model | Strengths | Limitations | Utilities | Validation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph fistula | Considered the gold standard due to its ability to study digestion, absorption, intracellular processing, and transport | Smaller intestinal VLDLs may get excluded; require extensive surgical procedure | High physiological relevance overall but may not be ideal for studying female animals | Recovery of fed fatty acid dose is typically 55–75% (the other 25–45% may bypass the lymph and enter the portal vein) [7,21,22] |

| Portal vein cannulation | Ideal for studying portal transport of dietary lipids | Larger intestinal lipoproteins get excluded; require extensive surgical procedure | Rarely used except for studying the physiology of portal transport | Recovery of fed fatty acid dose in portal vein should be around 39% [10] |

| Fecal analysis | Non-invasive and ideal for studying enterocyte uptake of dietary lipids (absorption) | Not generally used to study intracellular processing and transport | High physiological relevance for studying digestion and absorption | Less sensitive; 90% or more of fed fatty acid dose is absorbed [22,40,41] |

| Gavage + intestinal tissue analysis | No surgery involved; ability to provide morphological, molecular, and biochemical information | Require complementary data from other sample types to confirm findings | Provide some mechanical insights but isolation of intestinal lipoproteins is not possible | Complementary data from other sample types are often required; check for regurgitation [93] |

| Everted gut sac | Relatively easy to handle and less expensive | Short viability; not ideal for studying transport | Provide some mechanical insights; minimal isolation of intestinal lipoproteins | Tissue viability is a concern; experiments may need to be conducted within a day [50,51,52,53,54,55,56] |

| Human fetal gut | Ideal for studying the ontogeny of dietary fat absorption | Short viability; require special approval | Rarely used except for studying the development aspect of dietary fat absorption | Tissue viability is a concern; experiments may need to be conducted within a day [59,60,61] |

| Caco-2 | Commercially available and well characterized; cost-effective; complete lipoprotein recovery | Lack physiological complexity; chylomicron production is less robust | Can be used for detailed mechanistic studies | Isolated lipoproteins should be confirmed biochemically and microscopically [8,68,69] |

| IPEC-1 | Cost effective; complete lipoprotein recovery | Lack physiological complexity; require ApoA-IV overexpression to achieve robust chylomicron production | Can be used for detailed mechanistic studies | Isolated lipoproteins should be confirmed biochemically and microscopically [71,72,73,74] |

| Enteroids | Cells can be from any donor; robust chylomicron production; complete lipoprotein recovery | Lack physiological complexity; absence of physical separation between apical and basolateral compartments | Can be used for detailed mechanistic studies; allow donor cells to be used in the experiments | Isolated lipoproteins should be confirmed biochemically and microscopically [77,78] |

| Gut-on-a-chip | Can be designed to address a specific research question | Lack physiological complexity; not widely used yet for studying dietary fat absorption | Can be designed to study the mechanistic interaction of dietary fat absorption and other process | Isolated lipoproteins should be confirmed biochemically and microscopically [91,92] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nauli, A.M.; Phan, A.; Mai, K.; Tran, K.; Nauli, S.M. Guide for Selecting Experimental Models to Study Dietary Fat Absorption. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233644

Nauli AM, Phan A, Mai K, Tran K, Nauli SM. Guide for Selecting Experimental Models to Study Dietary Fat Absorption. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233644

Chicago/Turabian StyleNauli, Andromeda M., Ann Phan, Karen Mai, Kathleen Tran, and Surya M. Nauli. 2025. "Guide for Selecting Experimental Models to Study Dietary Fat Absorption" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233644

APA StyleNauli, A. M., Phan, A., Mai, K., Tran, K., & Nauli, S. M. (2025). Guide for Selecting Experimental Models to Study Dietary Fat Absorption. Nutrients, 17(23), 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233644