Evaluating the Impact of an 8-Week Family-Focused E-Health Lifestyle Program for Adolescents: A Retrospective, Real-World Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

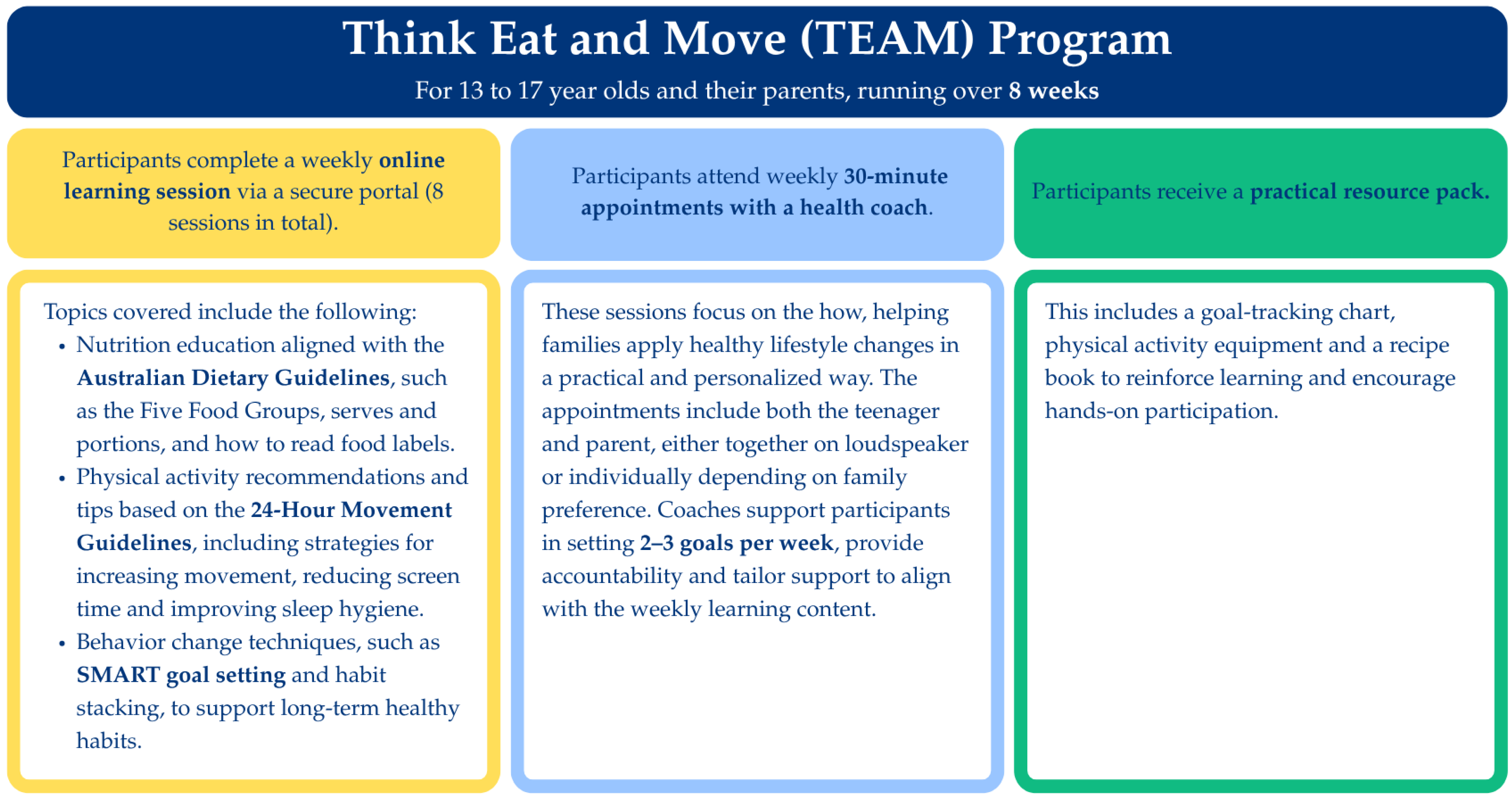

2.2. The TEAM Program

2.3. TEAM Program Participants

2.4. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

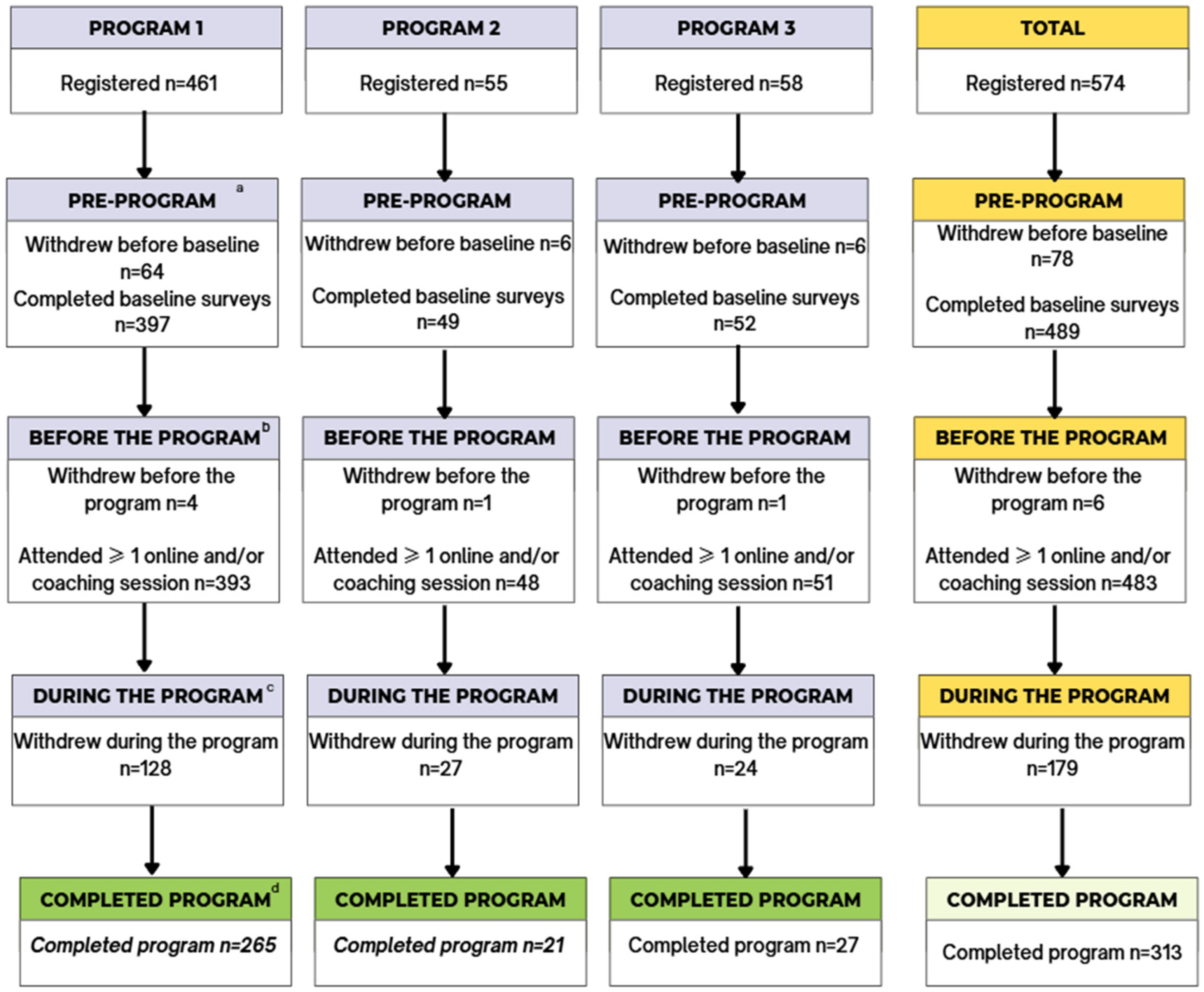

3.2. Program Adherence

3.3. Anthropometry

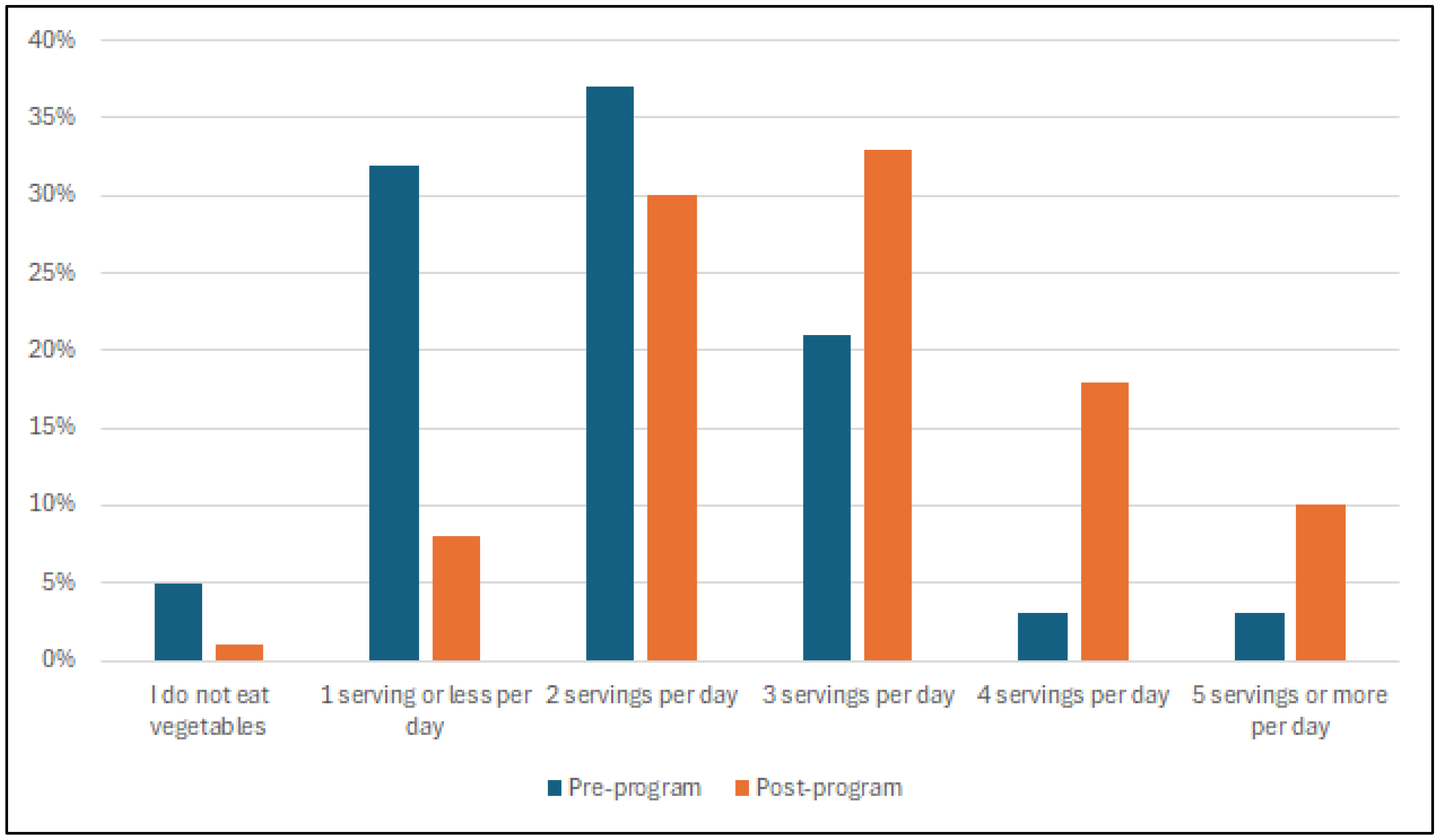

3.4. Eating Behaviors

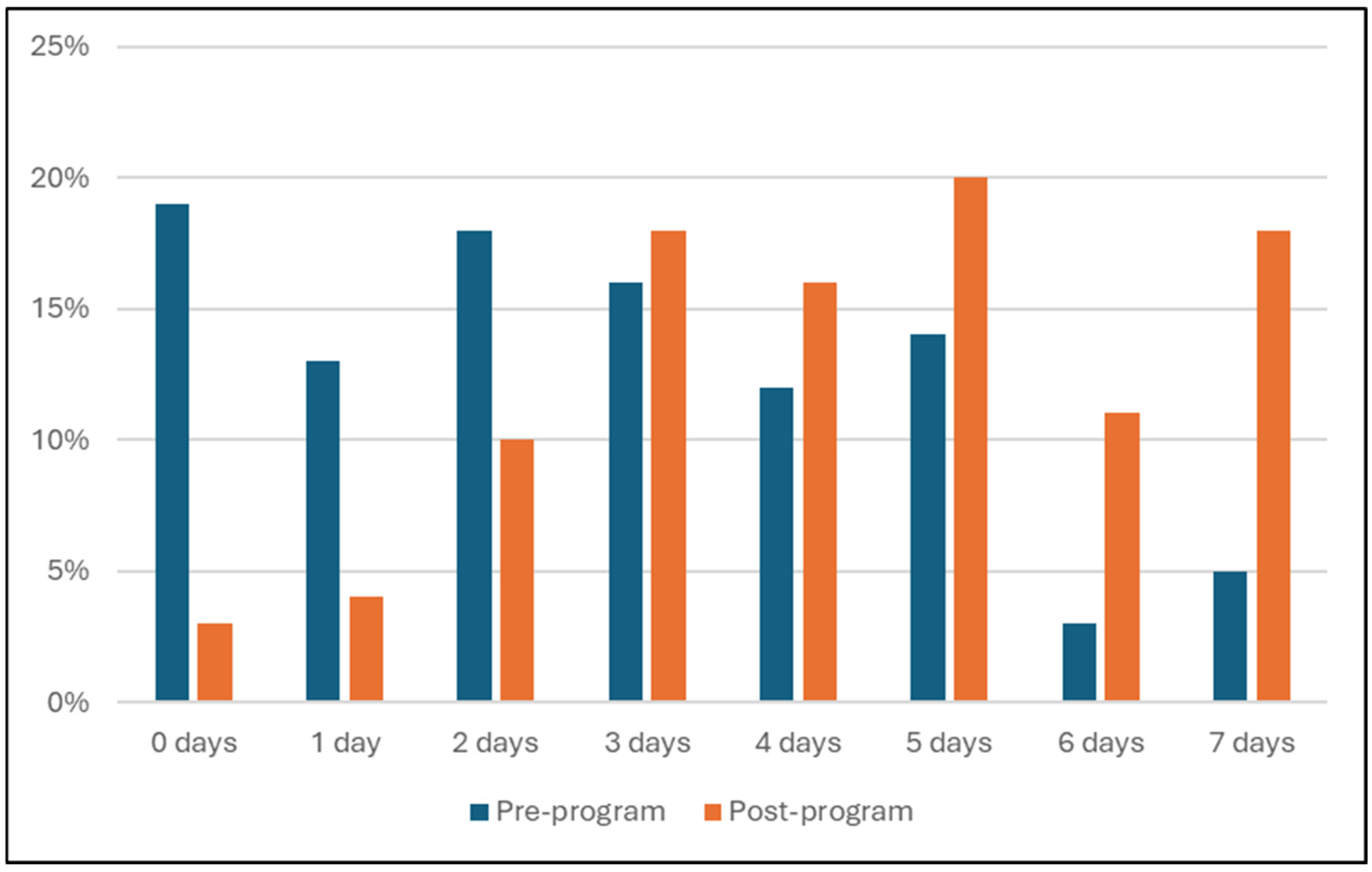

3.5. Physical Activity

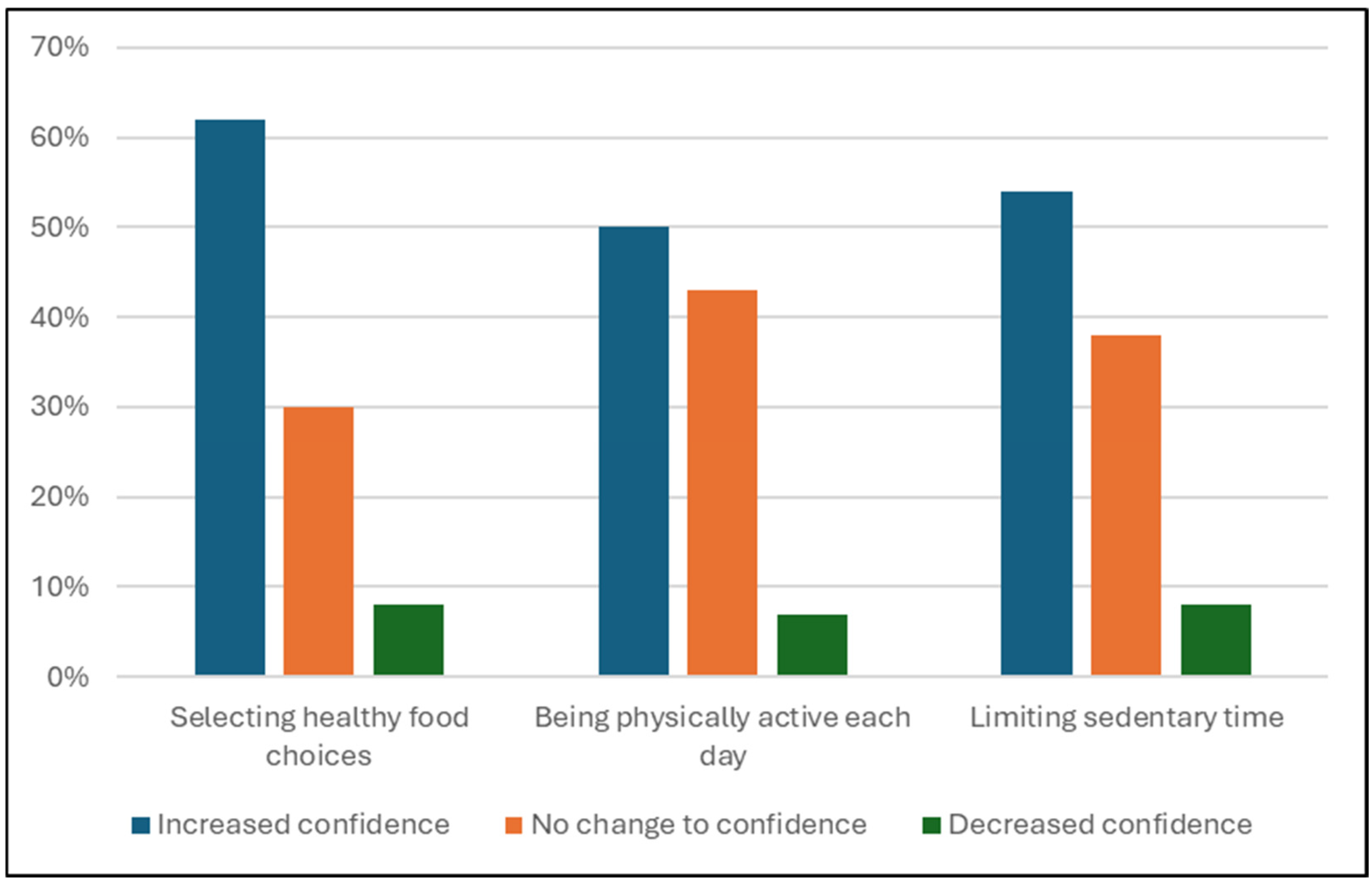

3.6. Knowledge and Confidence

3.7. Wellbeing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEIFA | Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas |

| TEAM | Think Eat And Move (program) |

References

- Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Overweight and Obesity; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2024.

- Rubino, F.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Cohen, R.V.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Brown, W.A.; Stanford, F.C.; Batterham, R.L.; Farooqi, I.S.; Farpour-Lambert, N.J.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 221–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Overweight and Obesity Among Australian Children and Adolescents; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Gangitano, E.; Barbaro, G.; Susi, M.; Rossetti, R.; Spoltore, M.E.; Masi, D.; Tozzi, R.; Mariani, S.; Gnessi, L.; Lubrano, C. Growth Hormone Secretory Capacity Is Associated with Cardiac Morphology and Function in Overweight and Obese Patients: A Controlled, Cross-Sectional Study. Cells 2022, 11, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansra, A.R.; Lakkunarajah, S.; Jay, M.S. Childhood and Adolescent Obesity: A Review. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 8, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendor, C.D.; Bardugo, A.; Pinhas-Hamiel, O.; Afek, A.; Twig, G. Cardiovascular morbidity, diabetes and cancer risk among children and adolescents with severe obesity. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinehr, T. Long-term effects of adolescent obesity: Time to act. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban Mohamed, M.A.; AbouKhatwa, M.M.; Saifullah, A.A.; Hareez Syahmi, M.; Mosaad, M.; Elrggal, M.E.; Dehele, I.S.; Elnaem, M.H. Risk Factors, Clinical Consequences, Prevention, and Treatment of Childhood Obesity. Children 2022, 9, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, M.; Llewellyn, A.; Owen, C.G.; Woolacott, N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastorci, F.; Lazzeri, M.F.L.; Vassalle, C.; Pingitore, A. The Transition from Childhood to Adolescence: Between Health and Vulnerability. Children 2024, 11, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Mills, K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, L.-J.; Vogel, M.; Stein, R.; Hilbert, A.; Breinker, J.L.; Böttcher, M.; Kiess, W.; Poulain, T. Mental health in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethy, G.; Samal, P.; Panda, M. Obesity in Children and Adolescents and its Impact on Mental Health. In Obesity-Current Science and Clinical Approaches; Srivastava, G., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odgers, C.L.; Schueller, S.M.; Ito, M. Screen Time, Social Media Use, and Adolescent Development. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 2, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrello, J. The Role of E-Health Interventions in Treating Adolescent Overweight and Obesity. The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. The Sax Institute. 2023. Available online: https://preventioncentre.org.au/news/the-role-of-e-health-interventions-in-treating-adolescent-overweight-and-obesity/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Shanley, A.; Johnstone, M.; Szewczyk, P.; Crowley, M. An exploration of Australian attitudes towards privacy. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2023, 31, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeside, R. Advancing adolescent health promotion in the digital era. Health Promot. Int. 2025, 40, daae172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, G.L.R.; Santo, R.E.; Mas Clavel, E.; Bosque Prous, M.; Koehler, K.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; van der Waerden, J.; Gobiņa, I.; López-Gil, J.F.; Lima, R.; et al. Digital dietary interventions for healthy adolescents: A systematic review of behavior change techniques, engagement strategies, and adherence. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 45, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Ahmed, M.; Staiano, A.E.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; Gough, C.; Petersen, J.M.; Yin, Z.; Vandelanotte, C.; Kracht, C.; Fiedler, J.; et al. Lifestyle eHealth and mHealth Interventions for Children and Adolescents: Systematic Umbrella Review and Meta–Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e69065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champion, K.E.; Newton, N.C.; Gardner, L.A.; Chapman, C.; Thornton, L.; Slade, T.; Sunderland, M.; Hides, L.; McBride, N.; O’Dean, S.; et al. Health4Life eHealth intervention to modify multiple lifestyle risk behaviours among adolescent students in Australia: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e276–e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Better Health Company. TEAMS Health Professional Information Document. Think, Eat and Move; Better Health Company: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2024; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Better Health Company. Privacy Policy—Better Health Company; Better Health Company: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Belconnen, Australia, 2021.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention. Data file for the Extended CDC BMI-for-age Growth Charts for Children and Adolescents; Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024.

- Mendelson, B.; Mendelson, M.; White, D. The Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults. J. Personal. Assess. 2001, 76, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, S.J.; Blais, M.A.; Gansler, D.A.; Sandberg, E.; Bistis, K.; LoCicero, A. Psychometric properties of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Overall and across demographic groups living within the United States. Eval. Health Prof. 2010, 33, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Educator Guide; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Hampl, S.E.; Hassink, S.G.; Skinner, A.C.; Armstrong, S.C.; Barlow, S.E.; Bolling, C.F.; Avila Edwards, K.C.; Eneli, I.; Hamre, R.; Joseph, M.M.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Obesity Collective. Obesity Evidence Hub: Managing Obesity in Children and Adolescents. Available online: https://www.obesityevidencehub.org.au/collections/treatment/managing-overweight-and-obesity-in-children-and-adolescents (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Overweight and Obesity Management. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng246 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Qiu, L.T.; Sun, G.X.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.D.; Wang, D.; Fan, B.Y. Effectiveness of multiple eHealth-delivered lifestyle strategies for preventing or intervening overweight/obesity among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 3, 999702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, L.B.; Stephenson, J.; Ells, L.; Adu-Ntiamoah, S.; DeSmet, A.; Giles, E.L.; Haste, A.; O’Malley, C.; Jones, D.; Chai, L.K.; et al. The effectiveness of e-health interventions for the treatment of overweight or obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Dordevic, A.L.; Gibson, S.; Davidson, Z.E. The effectiveness of a 10-week family-focused e-Health healthy lifestyle program for school-aged children with overweight or obesity: A randomised control trial. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, M.; Johnson, K.; Gray, V.; Mullur, R.; Gutierrez, E.; Dionico, P. Telehealth-Based Health Coaching Increases m-Health Device Adherence and Rate of Weight Loss in Obese Participants. Telemed. E-Health 2020, 26, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskin, C.J.; Cooper, K.; Stephens, L.D.; Peeters, A.; Salmon, J.; Porter, J. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity published internationally: A scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, L.K.; Farletti, R.; Fathi, L.; Littlewood, R. A Rapid Review of the Impact of Family-Based Digital Interventions for Obesity Prevention and Treatment on Obesity-Related Outcomes in Primary School-Aged Children. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, M. Mobile phone interventions to improve adolescents’ physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nurs. 2019, 36, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonham, M.P.; Dordevic, A.L.; Ware, R.S.; Brennan, L.; Truby, H. Evaluation of a Commercially Delivered Weight Management Program for Adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2017, 185, 73–80.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dietvorst, E.; de Vries, L.P.; van Eijl, S.; Mesman, E.; Legerstee, J.S.; Keijsers, L.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; Vreeker, A. Effective elements of eHealth interventions for mental health and well-being in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241294105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterveen, E.; Tzelepis, F.; Ashton, L.; Hutchesson, M.J. A systematic review of eHealth behavioral interventions targeting smoking, nutrition, alcohol, physical activity and/or obesity for young adults. Prev. Med. 2017, 99, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Knight, A.; Todd, A.; McGill, B.; Wardak, S.; Alston, L.; Livingstone, K.M.; Singleton, A.; Thornton, L.; Jia, S.; et al. Addressing disparities: A systematic review of digital health equity for adolescent obesity prevention and management interventions. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Dordevic, A.L.; Davidson, Z.E.; Gibson, S. Families’ Experiences With Family-Focused Web-Based Interventions for Improving Health: Qualitative Systematic Literature Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e58774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Redfern, J. Strategies to Engage Adolescents in Digital Health Interventions for Obesity Prevention and Management. Healthcare 2018, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umano, G.R.; Masino, M.; Cirillo, G.; Rondinelli, G.; Massa, F.; Mangoni di Santo Stefano, G.S.R.C.; Di Sessa, A.; Marzuillo, P.; Miraglia del Giudice, E.; Buono, P. Effectiveness of Smartphone App for the Treatment of Pediatric Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Children 2024, 11, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvicini, L.; Pingani, I.; Venturelli, F.; Patrignani, N.; Bassi, M.C.; Broccoli, S.; Ferrari, F.; Gallelli, T.; Panza, C.; Vicentini, M.; et al. Effectiveness of mobile health interventions targeting parents to prevent and treat childhood Obesity: Systematic review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 29, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tully, L.; Burls, A.; Sorensen, J.; El-Moslemany, R.; O’Malley, G. Mobile Health for Pediatric Weight Management: Systematic Scoping Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e16214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, L.K.; Collins, C.E.; May, C.; Holder, C.; Burrows, T.L. Accuracy of Parent-Reported Child Height and Weight and Calculated Body Mass Index Compared With Objectively Measured Anthropometrics: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrello, J.; Hayes, A.; Baur, L.A.; Lung, T. Potential cost-effectiveness of e-health interventions for treating overweight and obesity in Australian adolescents. Pediatr. Obes. 2023, 18, e13003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome Measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Anthropometry (Program 1 and 2 only) | Standing height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured either by a caregiver or a health professional using their own scales. BMI was calculated as weight/height(m)2. Measurements were converted into a z-score using reference data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [25]. |

| Eating Habits | Ten-question multiple choice survey assessing weekly dietary intake including drinks, snacks, discretionary food items and meals eaten at night in front of the television (qualitative assessment only). |

| Physical Activity | Six-question survey consisting of four multiple choice and two open-answer questions about physical activity and sedentary habits during the week. |

| Knowledge Questions | Five-question multiple choice survey based on current knowledge and feelings towards nutrition and PA and confidence relating to healthy eating habits and being physically active. |

| Self-Esteem and Body Esteem (Program 1 only) | “Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults” Medelson and White. This tool assesses general feelings about an individual’s current appearance, weight satisfaction and body appearance [26]. The survey consists of 23 questions on a 5-point Likert scale. Each question receives a score between 0 and 4 for a maximum total score of 92. Higher scores indicate a higher level of self- and body esteem. |

| Self-Perception (Program 1 only) | Adaptation of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [27], a validated tool that allows respondents to reflect on self-perception. The tool was altered to suit the age demographic of participants. The survey consists of ten questions on a 4-point Likert scale, each question scoring between 0 and 3 for a maximum score of 30. A higher score indicates a higher level of self- and body esteem. |

| Wellbeing | The Wellbeing survey consists of five questions on a 6-point Likert scale asking respondents to reflect on their quality of life and emotions over the past two weeks. |

| Withdrew Before Pre-Program a | Withdrew Before the Program b | Withdrew During the Program c | Completed Program d | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 574 | 76 | 6 | 179 | 313 | n/a |

| Age at start, median (IQR) | 15.0 (13.8–15.7) | 14.5 (13.3–15.4) | 14.5 (13.6–15.9) | 14.4 (13.7–15.8) | 0.77 e |

| Sex at birth | |||||

| Female | 32 (42) | 3 (50) | 101 (56) | 176 (56) | 0.15 f |

| Male | 44 (58) | 3 (50) | 78 (44) | 137 (44) | |

| Referring Health Professional | |||||

| Dentist | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | n/a |

| Dietitian/nutritionist | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 5 (3) | 8 (3) | |

| GP/doctor | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 10 (6) | 28 (9) | |

| Medical/surgical specialist | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 12 (7) | 18 (6) | |

| Nurse | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 19 (11) | 21 (7) | |

| Other g | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Not specified | 60 (79) | 6 (100) | 132 (73) | 233 (74) | |

| SEIFA decile n = 567 | |||||

| 1 | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 10 (6) | 11 (42) | 0.21 f |

| 2 | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 11 (6) | 10 (3) | |

| 3 | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 14 (8) | 10 (3) | |

| 4 | 7 (9) | 1 (17) | 15 (8) | 15 (5) | |

| 5 | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 7 (2) | |

| 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| 7 | 8 (11) | 1 (17) | 21 (12) | 32 (10) | |

| 8 | 12 (16) | 2 (33) | 20 (11) | 35 (11) | |

| 9 | 13 (17) | 0 (0) | 28 (16) | 83 (27) | |

| 10 | 21 (28) | 2 (33) | 52 (29) | 105 (34) | |

| Withdrawal reason | |||||

| Time/location does not suit the participant | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | - | n/a |

| No longer interested | 7 (9) | 0 (0) | 13 (7) | - | |

| Medical reasons | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | - | |

| Not the right time | 19 (25) | 1 (17) | 32 (18) | - | |

| Ineligible due to BMI criteria h | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 7 (4) | - | |

| Planning to engage in future program | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | - | |

| Reason not specified | 43 (57) | 5 (83) | 118 (66) | - | |

| Attendance (mean ± SD) | n/a | ||||

| Online sessions j | - | - | 3.8 ± 3.1 | 8.6 ± 1.0 | |

| Coaching sessions k | - | - | 4.0 ± 3.2 | 8.8 ± 1.2 | |

| Program 1 (n = 262) | Program 2 (n = 19) a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Program | Post-Program | Change | p-Value | Pre-Program | Post-Program | Change | p-Value | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.6 (25.3, 32.5) | 27.7 (24.2, 31.6) | −0.8 (−1.7, −0.1) | <0.001 | 21.6 (18.5, 28.6) | 22.2 (18.9, 27.7) | 0.0 (−0.6, 0.9) | 0.97 |

| Height (cm) | 164.3 (158.5, 170.5) | 165.0 (160.0, 172.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | <0.001 | 165.0 (156.0, 172.0) | 165.0 (158.0, 172.0) | 0.0 (−1.0, 2.0) | 0.59 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.0 (65.5, 92.0) | 77.0 (64.0, 90.0) | −1.0 (−3.1, 0.5) | <0.001 | 60.0 (50.0, 71.0) | 56.0 (52.0, 73.0) | 0.0 (−1.0, 2.0) | 0.47 |

| BMI z-score | 1.75 (1.4, 2.2) | 1.65 (1.1, 2.1) | −0.10 (−0.2, 0.0) | <0.001 | 0.87 (−0.3, 1.6) | 1.03 (0.1, 1.6) | 0.16 (−0.2, 0.1) | 0.71 |

| Height z-score | 0.22 (−0.5, 1.1) | 0.36 (−0.4, 1.3) | 0.14 (−0.0, 0.2) | <0.001 | 0.71 (−0.2, 1.3) | 0.30 (−0.2, 1.4) | −0.41 (−0.2, 0.1) | 0.98 |

| Weight z-score | 1.79 (1.2, 2.3) | 1.70 (1.0, 2.2) | −0.09 (−0.2, 0.0) | <0.001 | 0.63 (0.2, 1.9) | 0.65 (0.2, 2.1) | 0.02 (−0.2, 0.1) | 0.84 |

| Pre-Program | Post-Program | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit | I do not eat fruit | 16 (5) | 2 (1) | <0.001 |

| 1 serving or less per day | 109 (35) | 36 (12) | ||

| 2 servings per day | 121 (39) | 171 (55) | ||

| 3 servings per day | 51 (17) | 73 (24) | ||

| 4 servings or more per day | 12 (4) | 27 (9) | ||

| Vegetables | I do not eat vegetables | 14 (5) | 2 (1) | <0.001 |

| 1 serving or less per day | 99 (32) | 25 (8) | ||

| 2 servings per day | 113 (37) | 92 (30) | ||

| 3 servings per day | 64 (21) | 103 (33) | ||

| 4 servings per day | 10 (3) | 57 (18) | ||

| 5 servings or more per day | 9 (3) | 30 (10) | ||

| Water | I do not drink water | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Less than 1 cup per day | 9 (3) | 3 (1) | ||

| 1–2 cups per day | 33 (11) | 7 (2) | ||

| 2–3 cups per day | 59 (19) | 29 (9) | ||

| 3–4 cups per day | 66 (21) | 53 (17) | ||

| 4 cups or more | 141 (46) | 217 (70) | ||

| Soft drink | I do not drink soft drink | 70 (23) | 107 (35) | n/a a |

| Less than 1 cup per week | 100 (32) | 112 (36) | ||

| 1–3 cups per week | 95 (31) | 68 (22) | ||

| 4–6 cups per week | 22 (7) | 22 (7) | ||

| 1–2 cups per day | 14 (5) | 6 (2.0) | ||

| 2–3 cups per day | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | ||

| 3 or more cups per day | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | ||

| Fried potato | Never or rarely | 38 (12) | 80 (26) | n/a a |

| Less than once a week | 117 (38) | 129 (42) | ||

| 1–2 times a week | 115 (37) | 89 (29) | ||

| 3–4 times a week | 30 (10) | 10 (3) | ||

| 5–6 times a week | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Once a day | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | ||

| 2 or more times a day | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Take-away | Never or rarely | 64 (21) | 94 (30) | <0.001 |

| Less than once a week | 104 (34) | 143 (46) | ||

| 1–2 times a week | 114 (37) | 65 (21) | ||

| 3–4 times a week | 23 (7) | 7 (2) | ||

| 5–6 times a week | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Once a day | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| 2 or more times a day | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Meal while watching TV | Never or rarely | 179 (58) | 204 (66) | 0.005 |

| 1 day a week | 25 (8) | 32 (10) | ||

| 2 days a week | 14 (5) | 20 (7) | ||

| 3 days a week | 24 (8) | 16 (5) | ||

| 4 days a week | 7 (2) | 9 (3) | ||

| 5 days a week | 10 (3) | 10 (3) | ||

| 6 days a week | 7 (2) | 2 (1) | ||

| 7 days a week | 43 (14) | 16 (5) | ||

| Sweet/savory snacks | Never or rarely | 24 (8) | 47 (15) | <0.001 |

| Less than once a week | 45 (15) | 101 (33) | ||

| 1–2 times a week | 79 (26) | 94 (30) | ||

| 3–4 times a week | 59 (19) | 37 (12) | ||

| 5–6 times a week | 29 (9) | 11 (4) | ||

| Once a day | 34 (11) | 14 (5) | ||

| 2 or more times a day | 39 (13) | 5 (2) | ||

| Confectionery | Never or rarely | 36 (11) | 71 (23) | <0.001 |

| Less than once a week | 71 (23) | 115 (37) | ||

| 1–2 times a week | 102 (33) | 92 (30) | ||

| 3–4 times a week | 22 (7) | 21 (7) | ||

| 5–6 times a week | 55 (18) | 5 (2) | ||

| Once a day | 22 (7) | 4 (1) | ||

| 2 or more times a day | 17 (6) | 1 (0) | ||

| Crisps | Never or rarely | 34 (11) | 74 (24) | <0.001 |

| Less than once a week | 76 (25) | 113 (37) | ||

| 1–2 times a week | 100 (32) | 83 (27) | ||

| 3–4 times a week | 62 (20) | 26 (8) | ||

| 5–6 times a week | 13 (4) | 9 (3) | ||

| Once a day | 14 (5) | 3 (1) | ||

| 2 or more times a day | 10 (3) | 1 (0) |

| Pre-Program | Post-Program | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over the past 7 days, on how many days did you participate in moderate to vigorous exercise? | 0 days | 58 (19 | 10 (3) | <0.001 | |

| 1 day | 38 (13) | 12 (4) | |||

| 2 days | 53 (18) | 30 (10) | |||

| 3 days | 49 (16) | 55 (18) | |||

| 4 days | 36 (12) | 48 (16) | |||

| 5 days | 43 (14) | 60 (20) | |||

| 6 days | 8 (3) | 32 (11) | |||

| 7 days | 15 (5) | 53 (18) | |||

| Time spent using a mobile phone, iPad, tablet, computer, gaming console or watching TV/DVD a | School day | 0–1 h | 18 (6) | 55 (18) | <0.001 |

| 1–2 h | 80 (27) | 133 (44) | |||

| 2–3 h | 73 (24) | 63 (21) | |||

| >3 h | 129 (43) | 49 (16) | |||

| Saturday | 0–1 h | 8 (3) | 23 (8) | <0.001 | |

| 1–2 h | 38 (13) | 87 (29) | |||

| 2–3 h | 68 (23) | 90 (30) | |||

| >3 h | 186 (62) | 100 (33) | |||

| Sunday | 0–1 h | 9 (3) | 30 (10) | <0.001 | |

| 1–2 h | 38 (13) | 93 (31) | |||

| 2–3 h | 85 (28) | 82 (27) | |||

| >3 h | 168 (56) | 95 (32) | |||

| Pre-Program | Post-Program | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Questions a | ||||

| How many meals and snacks should I aim to have each day for healthy, regular eating? | 143 (75) | 172 (91) | 0.001 | |

| How many servings of vegetables are recommended that I eat each day? | 46 (24) | 72 (38) | 0.004 | |

| When reading nutrition information panels, what sort of information should I look out for? | 102 (54) | 165 (87) | <0.001 | |

| How many minutes of physical activity is it recommended that I do each day? | 123 (65) | 162 (85) | <0.001 | |

| How much screen time is it recommended that I stick to each day? | 76 (40) | 108 (57) | 0.001 | |

| Total correct (mean ± SD) b | 2.58 ± 1.2 | 3.58 ± 1.0 | <0.001 c | |

| Confidence | ||||

| I feel confident in selecting healthy food choices | Strongly agree | 24 (13) | 67 (35) | <0.001 |

| Agree | 70 (37) | 99 (52) | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 71 (37) | 20 (11) | ||

| Disagree | 18 (10) | 3 (2) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 7 (4) | 1 (1) | ||

| I feel confident being physically active each day | Strongly agree | 30 (16) | 65 (34) | <0.001 |

| Agree | 69 (36) | 78 (41) | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 47 (25) | 34 (18) | ||

| Disagree | 34 (18) | 11 (6) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 10 (5) | 2 (1) | ||

| I feel confident limiting the amount of time I spend being sedentary | Strongly agree | 13 (7) | 13 (7) | 0.001 |

| Agree | 57 (30) | 75 (40) | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 65 (34) | 53 (28) | ||

| Disagree | 35 (18) | 13 (7) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 20 (11) | 7 (4) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hulland, S.; Obatoki, O.; Giardino, I.; Kirkman, C.; van Dam, M.; Airth, C.; Quin, L.; Goodger, B.; Davidson, Z.E. Evaluating the Impact of an 8-Week Family-Focused E-Health Lifestyle Program for Adolescents: A Retrospective, Real-World Evaluation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223509

Hulland S, Obatoki O, Giardino I, Kirkman C, van Dam M, Airth C, Quin L, Goodger B, Davidson ZE. Evaluating the Impact of an 8-Week Family-Focused E-Health Lifestyle Program for Adolescents: A Retrospective, Real-World Evaluation. Nutrients. 2025; 17(22):3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223509

Chicago/Turabian StyleHulland, Susan, Oluwadurotimi Obatoki, Isabella Giardino, Caley Kirkman, Monica van Dam, Cecilia Airth, Lucy Quin, Brendan Goodger, and Zoe E. Davidson. 2025. "Evaluating the Impact of an 8-Week Family-Focused E-Health Lifestyle Program for Adolescents: A Retrospective, Real-World Evaluation" Nutrients 17, no. 22: 3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223509

APA StyleHulland, S., Obatoki, O., Giardino, I., Kirkman, C., van Dam, M., Airth, C., Quin, L., Goodger, B., & Davidson, Z. E. (2025). Evaluating the Impact of an 8-Week Family-Focused E-Health Lifestyle Program for Adolescents: A Retrospective, Real-World Evaluation. Nutrients, 17(22), 3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223509