A Scoping Review on Nutrition Knowledge and Nutrition Literacy Among Pregnant Women and the Prevalence of Pregnancy Complications and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Peer-reviewed articles;

- Written in English;

- Pregnant study participants;

- Studies assessing NK or NL in pregnant women;

- Exploratory studies;

- Studies using surveys with a list of items measuring NK or NL;

- Assessment of NK or NL, either as an outcome or an independent variable;

- Studies reported how NK or NL was scored.

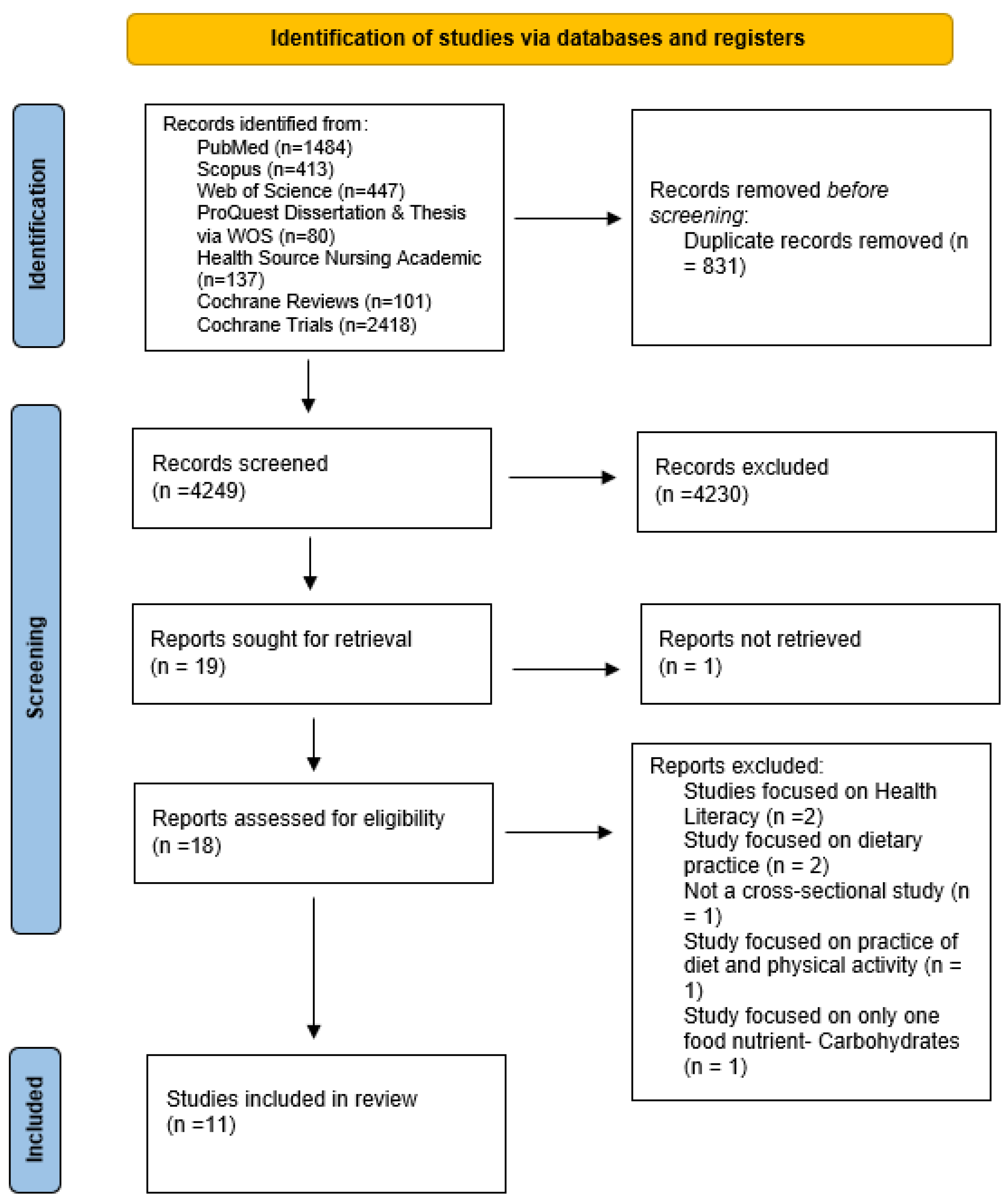

2.3. Literature Search and Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Summarizing

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Findings from the Reading

3.2.1. Education

3.2.2. Income

3.2.3. Occupation

3.2.4. Age

3.2.5. Health Insurance

3.2.6. Language and Culture

3.2.7. Family Influence

3.2.8. Parity

3.2.9. Pregnancy Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Study Strength and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GDM | Gestational Diabetics Mellitus |

| GNKQ | General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire |

| HDP | Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy |

| NK | Nutrition Knowledge |

| NL | Nutrition Literacy |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| US | United States |

| WIC | Women, Infants, and Children |

Appendix A

- #1.

- ((premature birth [mesh] OR “preterm birth*” [tiab] OR “early birth” [tiab] OR prematurity [tiab] OR “preterm delivery” [tiab] OR “preterm labor” [tiab]) OR (pregnancy complications [mesh] OR (hypertension [mesh] AND pregnancy [mesh])OR “preeclampsia” [tiab] OR “pre-eclampsia” [tiab] OR eclampsia [tiab] OR “hellp syndrome” [tiab] OR “gestational hypertension” [tiab] OR “hypertensive disorders of pregnancy” [tiab] OR “gestational diabetes” [tiab])) AND ((“nutritional literacy” [tiab:~2] OR “food literacy” [tiab:~2] OR “nutrition literacy” [tiab:~2] OR “food agency” [tiab] OR “nutri* education” [tiab] OR “diet* education” [tiab] OR “nutrition* awareness” [tiab] OR dietetics [mesh] OR ((“health literacy” [mesh] OR literacy [mesh]) AND (nutrition [mesh] OR nutrition [tiab] OR “feeding behavior” [mesh] OR food [mesh] OR food [tiab] OR diet [mesh] OR “eating pattern*” [tiab] OR diet [tiab] OR nutrients [mesh] OR nutrients [tiab]))

- #2.

- ((prenatal care [mesh] OR “prenatal care” [tiab] OR “maternal health” [tiab] OR “perinatal care” [tiab] OR “pregnancy care” [tiab] OR “prenatal period” [tiab] OR “perinatal period” [tiab] OR “gestation* period” [tiab])) AND (((“nutritional literacy” [tiab:~2] OR “food literacy” [tiab:~2] OR “nutrition literacy” [tiab:~2] OR “food agency” [tiab] OR “nutri* education” [tiab] OR “diet* education” [tiab] OR “nutrition* awareness” [tiab] OR dietetics [mesh] OR ((“health literacy” [mesh] OR literacy [mesh]) AND (nutrition [mesh] OR nutrition [tiab] OR “feeding”

- #3.

- (“Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice” [Mesh] OR “Health education” [Mesh] OR “health literacy” [tiab]) AND (nutrition [mesh] OR “Prenatal Nutritional Physiological Phenomena” [Mesh] OR nutritional status [mesh] nutrition [tiab] OR “feeding behavior” [mesh] OR diet [mesh] OR “eating pattern*” [tiab] OR diet [tiab] OR “diet* pattern*” [tiab] OR nutrients [mesh] OR nutrients [tiab] OR food [mesh] OR food* [tiab])) OR (“nutri* literacy” [tiab] OR “nutri* education” [tiab] OR “nutri* knowledge” [tiab] OR “nutri* counsel*” [tiab] OR “nutrition education and counselling” [tiab] OR “food literacy” [tiab] OR “food knowledge” [tiab] OR “food education” [tiab] OR “diet* knowledge” [tiab] OR “diet* education” [tiab] OR “food education” [tiab])) AND (“pregnancy complications” [MeSH Terms] OR “pregnan* complicat*” [Title/Abstract] OR “abnorm* pregnan*” [tiab] OR “pregnan* abnorm*” [tiab] OR “fetal abnorm*” [tiab] OR “neonatal abnorm*” [tiab] OR “birth defect*” [tiab] OR “gestational diabetes” [Title/Abstract] OR “eclampsia” [Title/Abstract] OR “pre-eclampsia” [Title/Abstract] OR “preterm birth” [Title/Abstract] OR “premature birth” [Title/Abstract] OR “fetal growth restriction” [Title/Abstract] OR “low birth weight” [Title/Abstract] OR “hellp syndrome” [Title/Abstract] OR “hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count” [tiab] OR “stillbirth” [Title/Abstract] OR “abortion” [Title/Abstract] OR “reproductive complication*” [tiab] OR “obstet* complicat*” [Title/Abstract] OR “birth complicat*” [Title/Abstract] OR “perinatal complicat*” [Title/Abstract] OR “labor complicat*” [Title/Abstract] OR “pregnancy induced hypertension” [Title/Abstract] OR “hypertensive disorders of pregnancy” [Title/Abstract] OR “fetal growth retardation” [Title/Abstract] OR “macrosomia” [Title/Abstract] OR “miscarriage*” [Title/Abstract] OR “pregnancy loss*” [tiab] OR “maternal mortality” [Title/Abstract] OR “fetal mortality” [Title/Abstract] OR “neonatal mortality” [Title/Abstract])behavior” [mesh] OR food [mesh] OR food [tiab] OR diet [mesh] OR “eating pattern*” [tiab] OR diet [tiab] OR nutrients [mesh] OR nutrients [tiab])))

References

- Demisew, M.; Fekadu Gemede, H.; Ayele, K. Prevalence of undernutrition and its associated factors among pregnant women in north Shewa, Ethiopia: A multi-center cross-sectional study. Womens Health 2024, 20, 17455057241290884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.T.; Ramirez, M.; Gajewski, B.J.; Sullivan, D.K.; Carlson, S.E.; Gibbs, H.D. Nutrition Literacy Among Latina/x People During Pregnancy Is Associated with Socioeconomic Position. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2022, 122, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Tan, B.; Murtaza, G.; Metwally, E.; Yang, H.; Kalhoro, M.S.; Kalhoro, D.H.; Chughtai, M.I.; Yin, Y. Role of Dietary Amino Acids and Nutrient Sensing System in Pregnancy Associated Disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 586979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmer, D.A.; Wallace, J.M.; Reynolds, L.P. Effect of nutrient intake during pregnancy on fetal and placental growth and vascular development. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2004, 27, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddana, T.Z. Factors associated with dietary practice and nutritional status of pregnant women in Dessie town, northeastern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaron BCaughey, M.P.; MTMD. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, N.D.; Cox, S.; Ko, J.Y.; Ouyang, L.; Romero, L.; Colarusso, T.; Ferre Cynthia, D.; Kroelinger Charlan, D.; Hayes Donald, K.; Barfield Wanda, D. Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy and Mortality at Delivery Hospitalization—United States, 2017–2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papežová, K.; Kapounová, Z.; Zelenková, V.; Riad, A. Nutritional Health Knowledge and Literacy among Pregnant Women in the Czech Republic: Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanlier, N.; Kocaay, F.; Kocabas, S.; Ayyildiz, P. The Effect of Sociodemographic and Anthropometric Variables on Nutritional Knowledge and Nutrition Literacy. Foods 2024, 13, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves Cdos, S.; Camargo, J.T.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Nakano, E.Y.; Ginani, V.C. Nutrition Literacy Level in Bank Employees: The Case of a Large Brazilian Company. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah Katherine Owens, B.; Barkley, R.; Paula Cupertino, A. Translation of a Nutrition Literacy Assessment Instrument for Use in the Latino Population of Greater Kansas City. Master’s Thesis, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’Oladebo, T. Assessing Nutrition Knowledge, Nutrition Literacy and the Prevalence of Pregnancy Complications and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Among Pregnant People. 2024. Available online: https://osf.io/6z5k2/overview (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Zelalem, T.; Mikyas, A.; Erdaw, T. Nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices among pregnant women who attend antenatal care at public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2018, 10, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezimu, W.; Bekele, F.; Habte, G. Pregnant mothers’ knowledge, attitude, practice and its predictors towards nutrition in public hospitals of Southern Ethiopia: A multicenter cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121221085843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei, E.A.; Afrifa, S.K.; Munkaila, A.; Gaa, P.K.; Kuugbee, E.D.; Mogre, V. Income Level but Not Nutrition Knowledge Is Associated with Dietary Diversity of Rural Pregnant Women from Northern Ghana. J. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 2021, 5581445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.N.; Jamil, R.; Tariq, S. Impact of Education on Knowledge of Women Regarding Food Intake During Pregnancy: A Hospital Based Study. Ann. Abbasi Shaheed Hosp. Karachi Med. Dent. Coll. 2020, 25, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Zein, M.M.; Sherif, A.; Essam, B.; Mahmoud, H. Nutrition and diet myths, knowledge and practice during pregnancy and lactation among a sample of Egyptian pregnant women: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, E.K.; Ní Riada, C.; O’Brien, R.; Minogue, H.; McCarthy, F.P.; Kiely, M.E. Access to nutrition advice and knowledge, attitudes and practices of pregnant women in Ireland: A cross-sectional study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 37, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagi, R.; Sahu, S.; Nagaraju, R. Oral health, nutritional knowledge, and practices among pregnant women and their awareness relating to adverse pregnancy outcomes. J. Indian Acad. Oral Med. Radiol. 2016, 28, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, N.; Cole, D.C.; Ouédraogo, H.Z.; Sindi, K.; Loechl, C.; Low, J.; Levin, C.; Kiria, C.; Kurji, J.; Oyunga, M. Health and nutrition knowledge, attitudes and practices of pregnant women attending and not-attending ANC clinics in Western Kenya: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heri, R.; Malqvist, M.; Yahya-Malima, K.I.; Mselle, L.T. Dietary diversity and associated factors among women attending antenatal clinics in the coast region of Tanzania. BMC Nutr. 2024, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aynaci, G. Nutrition perspective from the view of pregnant women: Their understanding of fetal well-being relative to their diet. Prog. Progress. Nutr. 2019, 21, 356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, H.D.; Ellerbeck, E.F.; Gajewski, B.; Zhang, C.; Sullivan, D.K. The Nutrition Literacy Assessment Instrument is a Valid and Reliable Measure of Nutrition Literacy in Adults with Chronic Disease. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 247–257.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmenter, K.; Wardle, J. Development of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 53, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beulen, Y.H.; Super, S.; Rothoff, A.; van der Laan, N.M.; de Vries, J.H.; Koelen, M.A.; Feskens, E.J.; Wagemakers, A. What is needed to facilitate healthy dietary behaviours in pregnant women: A qualitative study of Dutch midwives’ perceptions of current versus preferred nutrition communication practices in antenatal care. Midwifery 2021, 103, 103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasha, V.C.; Gerchow, L.; Lyndon, A.; Clark-Cutaia, M.; Wright, F. Understanding Food Insecurity as a Determinant of Health in Pregnancy Within the United States: An Integrative Review. Health Equity 2024, 8, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, A.; Parks, C.; Yaroch, A.; McKay, F.H.; Stern, K.; van der Pligt, P.; McNaughton, S.A.; Lindberg, R. Factors Associated with Food Insecurity among Pregnant Women and Caregivers of Children Aged 0–6 Years: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Sanghvi, T.; Tran, L.M.; Afsana, K.; Mahmud, Z.; Aktar, B.; Haque, R.; Menon, P. The nutrition and health risks faced by pregnant adolescents: Insights from a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbers, S. Functional health literacy in Spanish-speaking Latinas seeking breast cancer screening through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Program. Int. J. Womens Health 2009, 21, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentell, T.; Braun, K.L. Low Health Literacy, Limited English Proficiency, and Health Status in Asians, Latinos, and Other Racial/Ethnic Groups in California. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17 (Suppl. S3), 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutner, M.; Greenburg, E.; Jin, Y.; Paulsen, C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy; NCES 2006-483; National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, K.L.; Gibney, E.R.; McAuliffe, F.M. Maternal nutrition among women from Sub-Saharan Africa, with a focus on Nigeria, and potential implications for pregnancy outcomes among immigrant populations in developed countries. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 25, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.C.; Senekal, M.; Dodge, N.C.; Bechard, L.J.; Meintjes, E.M.; Molteno, C.D.; Duggan, C.P.; Jacobson, J.L.; Jacobson, S.W. Maternal Alcohol Use and Nutrition During Pregnancy: Diet and Anthropometry. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 41, 2114–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoms-Young, A.; Brown, A.G.M.; Agurs-Collins, T.; Glanz, K. Food Insecurity, Neighborhood Food Environment, and Health Disparities: State of the Science, Research Gaps and Opportunities. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.; St John, M.; Defranco, E.; Kelly, E. Food Insecurity in an Urban Pregnancy Cohort. Am. J. Perinatol. 2023, 40, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.; Elliott, S.; Hardison-Moody, A. The structural roots of food insecurity: How racism is a fundamental cause of food insecurity. Sociol Compass 2021, 15, e12846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.; Olander, E.K.; Salmon, D. Healthcare professionals’ views on supporting young mothers with eating and moving during and after pregnancy: An interview study using the COM-B framework. Health Soc Care Community 2020, 28, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, B.S.Q.; Vadakekut, E.S.; Mahdy, H. Gestational Diabetes. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024; Volume 14, p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Ibikunle, H.A.; Okafor, I.P.; Adejimi, A.A. Pre-natal nutrition education: Health care providers’ knowledge and quality of services in primary health care centres in Lagos, Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smorti, M.; Ginobbi, F.; Simoncini, T.; Pancetti, F.; Carducci, A.; Mauri, G.; Gemignani, A. Anxiety and depression in women hospitalized due to high-risk pregnancy: An integrative quantitative and qualitative study. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 5570–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, W.; Shih, T.; Incerti, D.; Ton, T.G.; Lee, H.C.; Peneva, D.; Macones, G.A.; Sibai, B.M.; Jena, A.B. Short-term costs of preeclampsia to the United States health care system. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 237–248.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, K.A.; Briss, P.A. An Ounce of Prevention Is Still Worth a Pound of Cure, Especially in the Time of COVID-19. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, E03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.; Lupton, D. The New Public Health: Health and Self in the Age of Risk. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.; Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D.; Hannan-Jones, M. Validation of a revised General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Title and Year | Years Study Was Conducted | Study Aim | Study Design and Methodology | Sample Size | Study’s Primary Focus | Country | Study’s Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant mothers’ knowledge, attitude, practice and its predictors towards nutrition in public hospitals of Southern Ethiopia: A multicenter cross-sectional study [15] | 2021–2022 | To assess pregnant women’s nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and practices, as well as the factors that influence them | Cross-Sectional Survey | 378 | Nutrition Knowledge | Ethiopia | Pregnant women’s nutritional knowledge (39.1% have low levels), attitude (40.5% have unfavorable attitudes), and practice (47.7% have poor practices) are low and are significantly associated with their educational status; various sociodemographic factors like occupation, parity, and income, as well as attitude itself, influence these outcomes, suggesting a need for enhanced nutritional counseling. |

| Nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices among pregnant women who attend antenatal care at public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [14] | 2015–2018 | To assess the nutritional knowledge, attitudes, and practices of pregnant women who attend antenatal care at public hospitals | Cross-Sectional Survey | 322 | Nutrition knowledge | Ethiopia | The study revealed low nutritional knowledge (27%), poor attitudes (48.4%), and poor practices (34.5%) among pregnant women. Educational status, family income, and attitude were significantly associated with nutritional knowledge. |

| Income Level but Not Nutrition Knowledge Is Associated with Dietary Diversity of Rural Pregnant Women from Northern Ghana [16] | 2020–2021 | To evaluate the nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and dietary diversity of pregnant women and to investigate the sociodemographic factors that determine their dietary diversity | Cross-Sectional Survey | 130 | Nutrition knowledge | Ghana | The study found that pregnant women’s nutrition knowledge was limited (mean score: 2.65 out of 5) but it is not a significant determinant of dietary diversity. |

| Impact of Education on Knowledge of Women Regarding Food Intake During Pregnancy: A Hospital Based Study [17] | 2016–2020 | To evaluate the nutritional knowledge of pregnant women concerning their food intake during pregnancy and to determine if there is an association between their level of education and their nutritional knowledge | Cross-Sectional Survey | 378 | Nutrition Knowledge | Pakistan | The study’s major findings indicate that the nutritional knowledge of pregnant women is generally limited. NK was found to be associated with education level and socioeconomic status. |

| Nutrition and diet myths, knowledge and practice during pregnancy and lactation among a sample of Egyptian pregnant women: a cross-sectional study [18] | 2022–2024 | To assess the nutritional knowledge, belief in nutritional myths, and practices of pregnant women | Cross-Sectional Survey | 468 | Nutrition Knowledge | Egypt | This study found that the nutrition knowledge among older pregnant women was higher than that of younger pregnant women. |

| Access to nutrition advice and knowledge, attitudes and practices of pregnant women in Ireland: A cross—sectional study [19] | 2024 | To explore the relationship between pregnant women’s access to nutrition advice, their nutrition knowledge, and their attitudes and practices regarding nutrition | Cross-Sectional Survey | 446 | Nutrition Knowledge | Ireland | This study found that pregnant women with previous nutrition counseling had significantly better NK scores than those without (80.0% vs. 73.3%). |

| Oral health, nutritional knowledge, and practices among pregnant women and their awareness relating to adverse pregnancy outcomes [20] | 2015–2016 | To assess the nutritional knowledge of pregnant women and to evaluate their oral health-related awareness and practices | Cross-Sectional Survey | 112 | Nutrition Knowledge | India | The study’s findings indicate that pregnant women had limited specific nutritional knowledge. A minority of participants correctly knew the meaning of food (40.1%), the importance of food during pregnancy (45.5%), what a balanced diet is (47%), and the difference between healthy and unhealthy foods (43.9%). |

| Nutrition Literacy Among Latina/x People During Pregnancy Is Associated With Socioeconomic Position [2] | 2018–2022 | To assess the nutrition literacy level of Latina/x people during pregnancy and to explore the association between nutrition literacy and socioeconomic position (SEP) | Cross-Sectional Survey | 979 | Nutrition Literacy | United States | The study found that a majority of the 112 participating pregnant Latina/x people had a low nutrition literacy level, with a mean score of 24.7 (a score ≤ 28 indicates low nutrition literacy). |

| Health and nutrition knowledge, attitudes and practices of pregnant women attending and not-attending ANC clinics in Western Kenya: a cross-sectional analysis [21] | 2011–2013 | To compare the nutrition knowledge and health knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of pregnant women who attended antenatal care clinics versus those who did not | Cross-Sectional Survey | 338 | Nutrition Knowledge | Kenya | The study found no significant difference in NK between pregnant women who attended antenatal care clinics and those who did not, with a mean Nutrition Knowledge Score (NKS) of 4.6 out of 11 for both groups. |

| Dietary diversity and associated factors among women attending antenatal clinics in the coast region of Tanzania [22] | 2020–2024 | To assess dietary diversity and its associated factors, which explicitly included nutrition knowledge, among pregnant women attending antenatal care | Cross-Sectional Survey | 369 | Nutrition Knowledge | Tanzania | The study found that the overall level of nutrition knowledge among pregnant women was low, with only 18% (number = 59) considered to have a high level of nutrition knowledge. |

| Nutrition perspective from the view of pregnant women: their understanding of fetal well-being relative to their diet [23] | 2019 | To assess the nutritional habits and the levels of nutritional knowledge among pregnant women | Cross-Sectional Survey | 338 | Nutrition Knowledge | Turkey | The study found that NK was significantly lower in women with pregnancy complications like preeclampsia (total score of 51.89) and higher in those with more education (total score of 63.04 for those with undergraduate/graduate degrees). |

| Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| Nutrition Knowledge | NK refers to the factual understanding a pregnant woman has about nutrition, including awareness of dietary guidelines, sources of nutrients, everyday food choices, and the relationship between diet and disease. It also includes the ability to recognize, recall, and apply food- and nutrition-related terminology [8,9]. The GNKQ is an instrument used to assess an individual’s level of nutrition knowledge [25]. |

| Nutrition Literacy | NL is the ability to interpret and use NK to make informed food choices and maintain a healthy diet. It includes practical skills and decision-making beyond basic knowledge [2,9,10]. It is assessed with the NLit instrument used to assign a score for an individual’s nutrition literacy level [24] |

| Health Literacy | Health literacy is the ability of individuals to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make informed decisions about their overall well-being. It encompasses a broad range of topics beyond nutrition, including physical activity, disease prevention, medication management, and navigating healthcare systems [11]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oladebo, T.; Bobholz, F.; Folivi, K.; Dickson-Gomez, J.; Anguzu, R.; Lopez, A.A.; Akinola, I.; Olson, J.; Palatnik, A. A Scoping Review on Nutrition Knowledge and Nutrition Literacy Among Pregnant Women and the Prevalence of Pregnancy Complications and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213488

Oladebo T, Bobholz F, Folivi K, Dickson-Gomez J, Anguzu R, Lopez AA, Akinola I, Olson J, Palatnik A. A Scoping Review on Nutrition Knowledge and Nutrition Literacy Among Pregnant Women and the Prevalence of Pregnancy Complications and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Nutrients. 2025; 17(21):3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213488

Chicago/Turabian StyleOladebo, Tinuola, Faith Bobholz, Kevin Folivi, Julia Dickson-Gomez, Ronald Anguzu, Alexa A. Lopez, Idayat Akinola, Jessica Olson, and Anna Palatnik. 2025. "A Scoping Review on Nutrition Knowledge and Nutrition Literacy Among Pregnant Women and the Prevalence of Pregnancy Complications and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes" Nutrients 17, no. 21: 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213488

APA StyleOladebo, T., Bobholz, F., Folivi, K., Dickson-Gomez, J., Anguzu, R., Lopez, A. A., Akinola, I., Olson, J., & Palatnik, A. (2025). A Scoping Review on Nutrition Knowledge and Nutrition Literacy Among Pregnant Women and the Prevalence of Pregnancy Complications and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Nutrients, 17(21), 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213488