AI-BASED Tool to Estimate Sodium Intake in STAGE 3 to 5 CKD Patients—The UniverSel Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

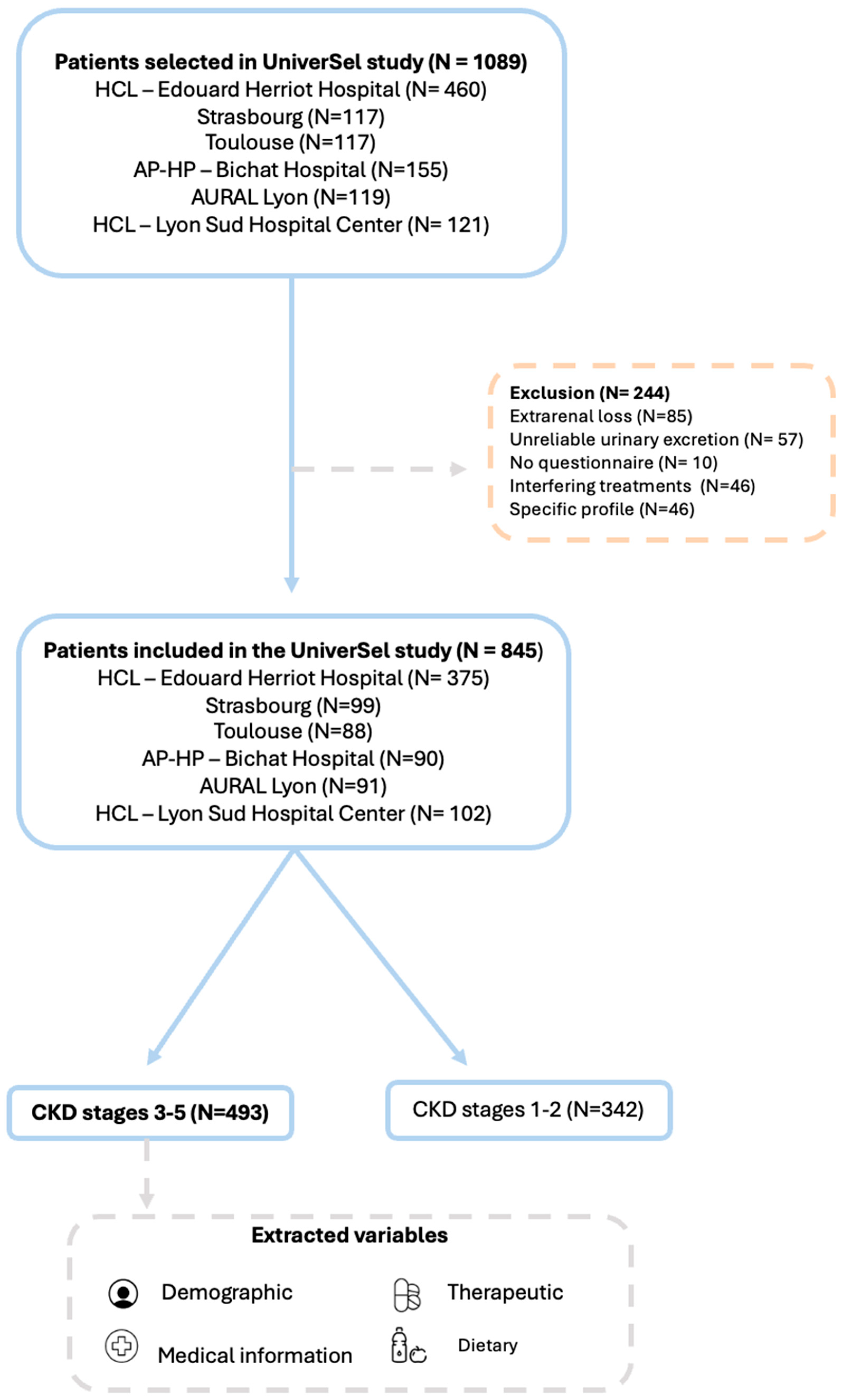

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

- Hôpital Lyon Sud—Hospices Civils de Lyon, Department of Nephrology;

- AURAL Lyon—Association for the Use of Artificial Kidney in the Lyon Region;

- Strasbourg University Hospitals, Department of Nephrology;

- Toulouse University Hospitals—CHU Rangueil, Department of Hypertension and Therapeutics;

- Assistance Publique—Hôpitaux de Paris, Bichat Claude Bernard Hospital, Department of Physiology and Functional Explorations;

- Hôpital Edouard Herriot—Hospices Civils de Lyon, Department of Nephrology, Hypertension, and Dialysis.

- Male or female aged 18 years or older, not opposed to participating in the study;

- Outpatient or day-hospital patient in a nephrology or hypertension unit;

- Having completed a 24-h urine collection within one month prior to inclusion as part of routine care, including urinary sodium analysis.

- (i)

- use of medications likely to interfere with 24-h natriuresis (e.g., sodium polystyrene sulfonate, locally acting antacids containing sodium, dietary supplements);

- (ii)

- extrarenal sodium losses due to intense sweating, intensive physical exercise, vomiting, diarrhea, or breastfeeding;

- (iii)

- individuals under legal protection (e.g., guardianship or curatorship).

2.3. Predictors and Outcome

2.4. Dietary Self-Questionnaire

- (i)

- the frequency of consumption of the following foods: bread, sandwich bread, pastries, cakes, breakfast cereals and/or biscuits, salted butter, cheese, processed meats, canned or smoked fish (e.g., tuna, sardines, smoked salmon, anchovies, mussels, or salted cod), pizzas, French fries, fast food and/or sandwiches, chips and/or salty snacks, ready-made meals, canned foods and/or industrial soups, salt added to cooking water, salt added at the table, meat or vegetable stock, commercial sauces, restaurant meals, and commercial carbonated mineral water;

- (ii)

- portion size, self-assessed by patients in comparison to peers of the same age, categorized as “less than,” “more than,” or “about the same as” peers.

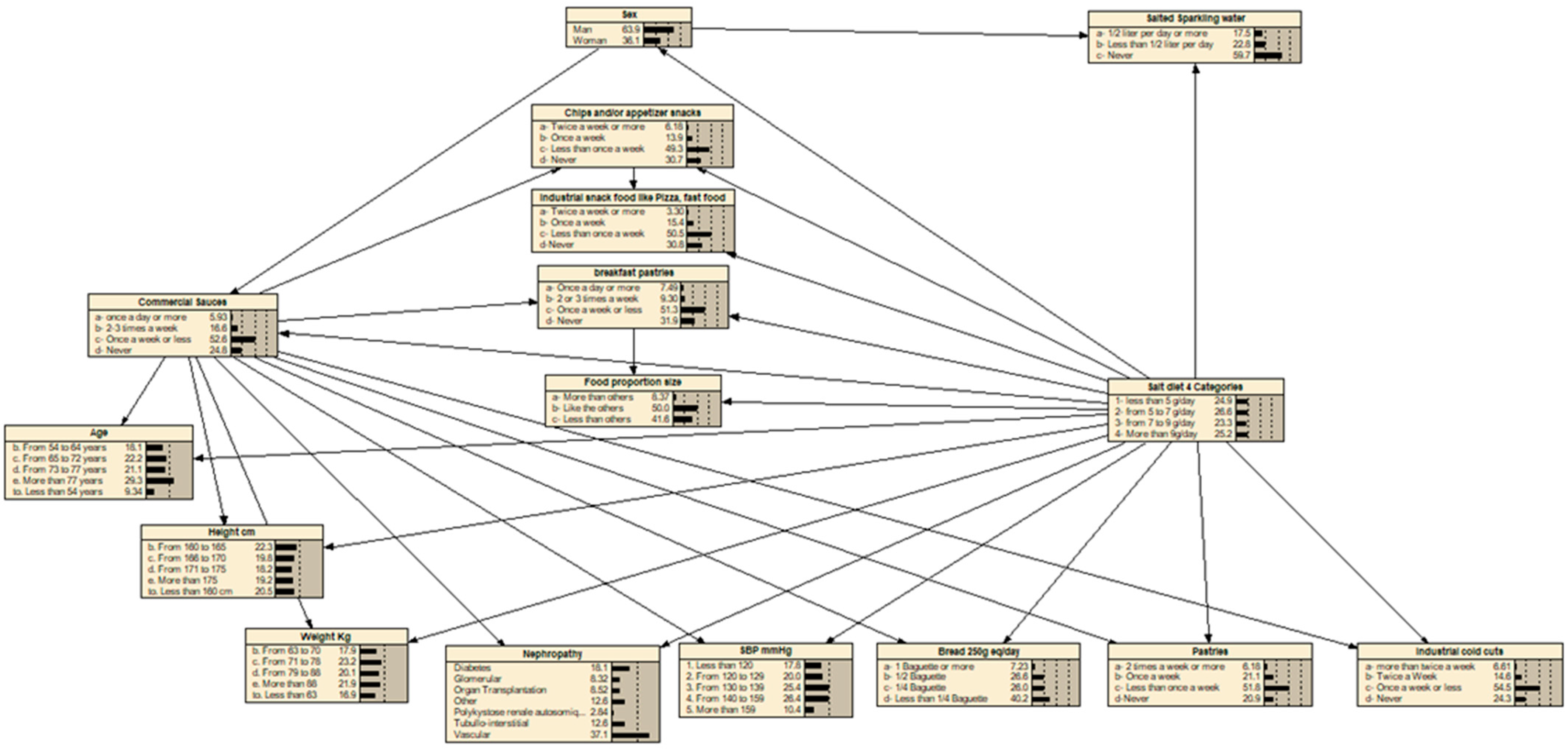

2.5. Prediction Model—Bayesian Network

- (i)

- each explanatory variable is directly connected to the target variable (i.e., 24-h urinary sodium excretion);

- (ii)

- each explanatory variable may also be connected to one other explanatory variable, through a single parent node;

- (iii)

- the final structure is the one that maximizes the total mutual information between the explanatory variables and the target, thereby optimizing predictive performance without increasing model complexity.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Variables Selected for the Development of the Sodium Intake Estimation Tool and Internal Validation to Estimate Sodium Intake

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADPKD | Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| eGFR | Estimation glomerular Filtration |

| EM | Expectation-Maximization |

| FFQ | Food frequency questionnaire |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TAN | Tree-Augmented Naive Bayes |

References

- Burnier, M.; Damianaki, A. Hypertension as Cardiovascular Risk Factor in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, J.; Floege, J.; Fliser, D.; Böhm, M.; Marx, N. Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathophysiological Insights and Therapeutic Options. Circulation 2021, 143, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameer, O.Z. Hypertension in chronic kidney disease: What lies behind the scene. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 949260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inserm. Hypertension Artérielle (HTA). Une Affection Cardiovasculaire Fréquente aux Conséquences Sévères. November 2, 2018. Available online: https://www.inserm.fr/dossier/hypertension-arterielle-hta/#:~:text=L'%C3%A2ge%20n'est%20pas%20le%20seul%20facteur%20de%20risque&text=Mais%20d'autres%20facteurs%20de,tabac%20ou%20encore%20l'alcool (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Vakilzadeh, N.; Phan, O.; Forni Ogna, V.; Wuerzner, G.; Burnier, M. Nouveaux aspects de la prise en charge de l’hypertension artérielle chez le patient insuffisant rénal chronique. Rev. Médicale Suisse 2014, 10, 1668–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Report on Sodium Intake Reduction, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, K.; Mullan, J.; Mansfield, K. An integrative review of the methodology and findings regarding dietary adherence in end stage kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginos, B.N.R.; Engberink, R.H.G.O. Estimation of Sodium and Potassium Intake: Current Limitations and Future Perspectives. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N.R.; He, F.J.; Tan, M.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Neal, B.; Woodward, M.; Cogswell, M.E.; McLean, R.; Arcand, J.; MacGregor, G.; et al. The International Consortium for Quality Research on Dietary Sodium/Salt (TRUE) position statement on the use of 24-h, spot, and short duration (<24 h) timed urine collections to assess dietary sodium intake. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2019, 21, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, R.M. Métodos de evaluación de la ingesta actual: Registro o diario dietético. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 21, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girerd, X.; Villeneuve, F.; Deleste, F.; Giral, P.; Rosenbaum, D. Mise au point et évaluation de l’ExSel Test pour dépister une consommation excessive de sel chez les patients hypertendus. Ann. Cardiol. D’Angéiol. 2015, 64, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villeneuve, F.; Lim, H.; Girerd, X. Conséquences de la réalisation du test ExSel® sur la consommation excessive de sel chez des patients hypertendus suivis en médecine générale. Ann. Cardiol. D’Angéiol. 2016, 65, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monntoya, L.M.; Ducher, M.; Florens, N.; Fauvel, J.P. Évaluation de l’autoquestionnaire ExSel® pour dépister une consommation excessive de sel chez les patients consultant en néphrologie. Ann. Cardiol. D’Angéiol. 2019, 68, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcand, J.; Abdulaziz, K.; Bennett, C.; L’Abbé, M.R.; Manuel, D.G. Developing a Web-based dietary sodium screening tool for personalized assessment and feedback. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granal, M.; Slimani, L.; Florens, N.; Sens, F.; Pelletier, C.; Pszczolinski, R.; Casiez, C.; Kalbacher, E.; Jolivot, A.; Dobourg, L.; et al. Prediction Tool to Estimate Potassium Diet in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Developed Using a Machine Learning Tool: The UniverSel Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robard Martin, C. Evaluation de la Consommation de sel en Pratique Medicale: Mise au Point d’un Auto-Questionnaire. Université de Limoges. 2011. Available online: https://cdn.unilim.fr/files/theses-exercice/M20113172.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Jallet, C. Evaluation de la Consommation de sel en Pratique Médicale: Validation d’un Auto-Questionnaire. Ph.D. Thesis, Universite de Limoges, Limofes, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Iwelomene, O.; Gougeon, A.; Burnier, M.; Belot, L.; Sourd, V.; Fauvel, J.P.; Granal, M. Dietary sodium reduction and blood pressure: A dose-response meta-analysis. Clin. Kidney J. accepted.

| All Centers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 493 | ||

| Sodium Intake | Percentage (%) | ||

| Less than 5 g/day | 24.9 | ||

| 5 to 6.9 g/day | 26.6 | ||

| 7 to 9 g/day | 23.3 | ||

| More than 9 g/day | 25.2 | ||

| Patient Characteristics | Mean | SD | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | |||

| M | 64 | ||

| F | 36 | ||

| Age (years) | 70 | 11 | |

| a. Less than 54 | 9.3 | ||

| b. 54 to 64 | 18.1 | ||

| c. 65 to 72 | 22.1 | ||

| d. 73 to 77 | 21.1 | ||

| e. More than 77 | 29.2 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 77 | 15 | |

| a. Less than 63 | 20.1 | ||

| b. 63 to 70 | 21.7 | ||

| c. 71 to 78 | 19.3 | ||

| d. 79 to 88 | 17.8 | ||

| e. More than 88 | 18.9 | ||

| Height (cm) | 167 | 9 | |

| a. Less than 160 | 16.8 | ||

| b. 160 to 165 | 17.8 | ||

| c. 166 to 170 | 23.1 | ||

| d. 171 to 175 | 20.1 | ||

| e. More than 175 | 21.9 | ||

| Nephropathy | |||

| Vascular | 37.1 | ||

| Diabetes | 18.1 | ||

| Tubulointerstitial | 12.6 | ||

| Other | 12.4 | ||

| Glomerular | 8.3 | ||

| Organ transplantation (liver, heart, pulmonary) | 8.2 | ||

| Autosomic dominant polycystic kidney disease | 2.8 | ||

| Stage of CKD | |||

| IIIa (45–59 mL/min) | 36.9 | ||

| IIIb (30–44 mL/min) | 39.1 | ||

| IV (15–29 mL/min) | 20.9 | ||

| V (<15 mL/min) | 3.0 | ||

| SBP (mmHg) | 137 | 21 | |

| 1. Less than 120 | 17.7 | ||

| 2. 120 to 129 | 20.0 | ||

| 3. 130 to 139 | 25.4 | ||

| 4. 140 to 159 | 26.3 | ||

| 5. More than 159 | 10.4 | ||

| DBP (mmHg) | 73 | 12 | |

| 1. Less than 80 | 70.5 | ||

| 2. 80 to 84 | 11.5 | ||

| 3. 85 to 89 | 9.6 | ||

| 4. More than 89 | 8.2 | ||

| Oedema (Yes) | 3.6 | ||

| Diabetes (Yes) | 33.5 | ||

| Heart failure | 9.9 | ||

| Biology | Mean | SD | Percentage (%) |

| CKD-EPI (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 39 | 12 | |

| 24-h Diuresis (L/24 h) | 2.0 | 0.7 | |

| 24-h Creatininuria (mmol/24 h) | 10.9 | 3.8 | |

| 24-h Natriuresis (mmol/24 h) | 123.5 | 49.5 | |

| Plasma Bicarbonates (mmol/L) | 24.5 | 3.2 | |

| Plasma creatinine (µmol/L) | 159.5 | 67.0 | |

| Plasma sodium (mmol/L) | 140 | 2.5 | |

| Variables | Percentage of Variance of Beliefs | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables included in the optimized Bayesian network | ||

| 1 | Weight | 4.94 |

| 2 | Height | 3.77 |

| 3 | Sex | 3.03 |

| 4 | Bread consumption | 2.22 |

| 5 | Nephropathy | 2.18 |

| 6 | Food Portion Size | 2.01 |

| 7 | Breakfast pastries consumption | 1.87 |

| 8 | Age | 1.85 |

| 9 | Commercial sauces consumption | 1.08 |

| 10 | Salted sparkling water consumption | 0.998 |

| 11 | Systolic blood pressure | 0.954 |

| 12 | Chips and/or appetizer snacks consumption | 0.947 |

| 13 | Pastries consumption | 0.893 |

| 14 | Industrial snack food like pizza, fast food consumption | 0.842 |

| 15 | Industrial cold cuts consumption | 0.818 |

| Variables not included in the optimized Bayesian network | ||

| 16 | Oedema | 0.791 |

| 17 | Mushrooms consumption | 0.63 |

| 18 | Kalemia | 0.613 |

| 19 | Heart Failure | 0.599 |

| 20 | Nephrotic syndrome | 0.583 |

| 21 | Chocolate consumption | 0.574 |

| 22 | Thiazides use | 0.497 |

| 23 | Furosemide use | 0.472 |

| 24 | Renin angiotensin system blockers use | 0.457 |

| 25 | Dry vegetables consumption | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Granal, M.; Florens, N.; Younes, M.; Fouque, D.; Koppe, L.; Vidal-Petiot, E.; Duly-Bouhanick, B.; Cartelier, S.; Sens, F.; Fauvel, J.-P. AI-BASED Tool to Estimate Sodium Intake in STAGE 3 to 5 CKD Patients—The UniverSel Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213398

Granal M, Florens N, Younes M, Fouque D, Koppe L, Vidal-Petiot E, Duly-Bouhanick B, Cartelier S, Sens F, Fauvel J-P. AI-BASED Tool to Estimate Sodium Intake in STAGE 3 to 5 CKD Patients—The UniverSel Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(21):3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213398

Chicago/Turabian StyleGranal, Maelys, Nans Florens, Milo Younes, Denis Fouque, Laetitia Koppe, Emmanuelle Vidal-Petiot, Béatrice Duly-Bouhanick, Sandrine Cartelier, Florence Sens, and Jean-Pierre Fauvel. 2025. "AI-BASED Tool to Estimate Sodium Intake in STAGE 3 to 5 CKD Patients—The UniverSel Study" Nutrients 17, no. 21: 3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213398

APA StyleGranal, M., Florens, N., Younes, M., Fouque, D., Koppe, L., Vidal-Petiot, E., Duly-Bouhanick, B., Cartelier, S., Sens, F., & Fauvel, J.-P. (2025). AI-BASED Tool to Estimate Sodium Intake in STAGE 3 to 5 CKD Patients—The UniverSel Study. Nutrients, 17(21), 3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213398