Human Milk Electrolytes as Nutritional Biomarkers of Mammary Gland Integrity: A Study Across Ductal Conditions and Donor Milk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Sample Collection and Handling

2.3. Electrolyte Analysis and Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Groups

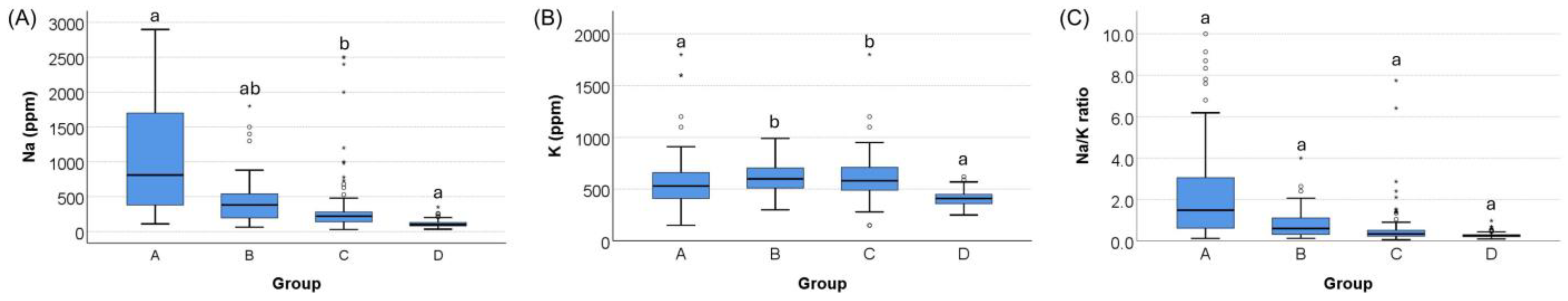

3.2. Na, K, and the Na/K Ratio Concentrations Across Groups

3.3. Group Comparison After Adjusting for Covariates

3.4. Discrimination Between Ductal Obstruction and Non-Obstructed Groups

3.5. Correlations with Maternal and Infant Characteristics

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Na | Sodium |

| K | Potassium |

| Na/K | Sodium-to-Potassium |

| GA | Gestational Age |

| BW | Birth Weight |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristics |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

Appendix A

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | B (SE) | 95% CI (Lower to Upper) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank Sodium (Na) | Group A vs. C + D | 196.86 (16.51) | 164.43 to 229.29 | <0.001 |

| Maternal age | 4.95 (1.20) | 2.59 to 7.31 | <0.001 | |

| Gestational age at birth | −1.18 (3.33) | −7.73 to 5.37 | 0.724 | |

| Infant birth weight | 0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 to 0.06 | 0.201 | |

| Infant age at milk expression | −4.98 (1.33) | −7.59 to −2.37 | <0.001 | |

| Storage duration | −0.83 (0.09) | −1.00 to −0.65 | <0.001 | |

| Rank Potassium (K) | Group A vs. C + D | 24. 67 (21.10) | −16.77 to 66.11 | 0.243 |

| Maternal age | 5.20 (1.53) | 2.18 to 8.22 | 0.001 | |

| Gestational age at birth | 10.69 (4.26) | 2.32 to 19.05 | 0.012 | |

| Infant birth weight | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.069 to 0.016 | 0.225 | |

| Infant age at milk expression | −5.74 (1.70) | −9.08 to −2.41 | 0.001 | |

| Storage duration | −0.59 (0.11) | −0.82 to −0.37 | <0.001 | |

| Rank Na/K ratio | Group A vs. C + D | 192.37 (18.43) | 156.17 to 228.57 | <0.001 |

| Maternal age | 2.66 (1.34) | 0.03 to 5.30 | 0.048 | |

| Gestational age at birth | −7.20 (3.72) | −14.51 to 0.11 | 0.053 | |

| Infant birth weight | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.003 to 0.08 | 0.033 | |

| Infant age at milk expression | −2.48 (1.48) | −5.39 to 0.44 | 0.095 | |

| Storage duration | −0.73 (0.10) | −0.93 to −0.54 | <0.001 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | B (SE) | 95% CI (Lower to Upper) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank Sodium (Na) | Group A vs. B + C + D | 172.89 (16.34) | 140.80 to 204.99 | <0.001 |

| Maternal age | 5.12 (1.20) | 2.77 to 7.47 | <0.001 | |

| Gestational age at birth | −0.25 (3.30) | −6.74 to 6.24 | 0.940 | |

| Infant birth weight | 0.02 (0.02) | −0.02 to 0.05 | 0.354 | |

| Infant age at milk expression | −4.35 (1.25) | −6.81 to −1.89 | 0.001 | |

| Storage duration | −0.99 (0.09) | −1.16 to −0.82 | <0.001 | |

| Rank Potassium (K) | Group A vs. B + C + D | 5.87 (20.64) | −34.66 to 46.40 | 0.776 |

| Maternal age | 5.91 (1.51) | 2.93 to 8.88 | <0.001 | |

| Gestational age at birth | 9.15 (4.17) | 0.96 to 17.34 | 0.029 | |

| Infant birth weight | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.06 to 0.02 | 0.365 | |

| Infant age at milk expression | −4.86 (1.58) | −7.97 to −1.75 | 0.002 | |

| Storage duration | −0.72 (0.11) | −0.93 to −0.51 | <0.001 | |

| Rank Na/K ratio | Group A vs. B + C + D | 174.17 (18.30) | 138.23 to 210.12 | <0.001 |

| Maternal age | 2.60 (1.34) | −0.03 to 5.24 | 0.053 | |

| Gestational age at birth | −5.52 (3.70) | −12.79 to 1.74 | 0.136 | |

| Infant birth weight | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.006 to 0.07 | 0.099 | |

| Infant age at milk expression | −2.15 (1.40) | −4.90 to 0.61 | 0.127 | |

| Storage duration | −0.86 (0.10) | −1.05 to −0.67 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Na (r) | Na (p-Value) | K (r) | K (p-Value) | Na/K (r) | Na/K (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | 0.172 | <0.001 | 0.147 | <0.001 | 0.109 | 0.006 |

| Gestational age at birth | 0.228 | <0.001 | 0.318 | <0.001 | 0.110 | 0.006 |

| Infant birth weight | 0.206 | <0.001 | 0.228 | <0.001 | 0.133 | 0.001 |

| Infant age at milk expression | −0.427 | <0.001 | −0.300 | <0.001 | −0.323 | <0.001 |

| Storage duration * | −0.237 | <0.001 | −0.025 | 0.612 | −0.309 | <0.001 |

References

- Ballard, O.; Morrow, A.L. Human milk composition: Nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2013, 60, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelwagen, K.; Farr, V.C.; McFadden, H.A. Alteration of the sodium to potassium ratio in milk and the effect on milk secretion in goats. J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, H.; Li, C.; Solomons, N.; Chomat, A.M.; Scott, M.; Koski, K. Comparison of breast milk sodium-potassium ratio, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and somatic cell count as potential biomarkers of subclinical mastitis (623.21). FASEB J. 2014, 28, 623.21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, M.; Wagner, E.A.; Chantry, C.J.; Dewey, K.G.; Nommsen-Rivers, L.A. The Relation between Breast Milk Sodium to Potassium Ratio and Maternal Report of a Milk Supply Concern. J. Pediatr. 2017, 181, 294–297.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, R.M.; Pace, C.D.W.; Fehrenkamp, B.D.; Price, W.J.; Lewis, M.; Williams, J.E.; McGuire, M.A.; McGuire, M.K. Sodium and Potassium Concentrations and Somatic Cell Count of Human Milk Produced in the First Six Weeks Postpartum and Their Suitability as Biomarkers of Clinical and Subclinical Mastitis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquerra-Zwiers, A.L.; Mulder, C.; Czmer, L.; Perecki, A.; Goris, E.D.; Lai, C.T.; Geddes, D. Associations of Secretory Activation Breast Milk Biomarkers with Breastfeeding Outcome Measures. J. Pediatr. 2023, 253, 259–265.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivlighan, K.T.; Schneider, S.S.; Browne, E.P.; Pentecost, B.T.; Anderton, D.L.; Arcaro, K.F. Mammary epithelium permeability during established lactation: Associations with cytokine levels in human milk. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1258905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, M.C.; Allen, J.C.; Archer, P.C.; Casey, C.E.; Seacat, J.; Keller, R.P.; Lutes, V.; Rasbach, J.; Neifert, M. Studies in human lactation: Milk volume and nutrient composition during weaning and lactogenesis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.P. Management of mastitis in breastfeeding women. Am. Fam. Physician 2008, 78, 727–731. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Mastitis: Causes and Management. Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development. 2000. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FCH-CAH-00.13 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Perrella, S.L.; Anderton-May, E.L.; McLoughlin, G.; Lai, C.T.; Simmer, K.N.; Geddes, D.T. Human Milk Sodium and Potassium as Markers of Mastitis in Mothers of Preterm Infants. Breastfeed. Med. 2022, 17, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Tanaka, M.; Date, M.; Miura, K.; Mizuno, K. Immunological Factors and Macronutrient Content in Human Milk From Women With Subclinical Mastitis. J. Hum. Lact. 2025, 41, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, K.; Mizuno, K.; Azuma, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Den, H.; Iyoda, M.; Nagao, S.; Tsujimori, Y. Reliability of an Ion-Selective Electrode as a Simple Diagnostic Tool for Mastitis. J. Hum. Lact. 2022, 38, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.T.; Gardner, H.; Geddes, D. Comparison of Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry with an Ion Selective Electrode to Determine Sodium and Potassium Levels in Human Milk. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Z.; Nguyen, T.D.D.; Ingebrandt, S.; Vu, X.T. Real-time and multiplexed detection of sodium and potassium ions using PEDOT:PSS OECT microarrays integrated with ion-selective membranes. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 507, 145111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquerra-Zwiers, A.; Vroom, A.; Geddes, D.; Lai, C.T. Use of a Portable Point-of-Care Instrumentation to Measure Human Milk Sodium and Potassium Concentrations. Breastfeed. Med. 2022, 17, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katrina, B.M.; Helen, M.J. Breast Conditions in the Breastfeeding Mother. In Breastfeeding: A Guide for the Medical Profession, 9th ed.; Ruth, A.L., Robert, M.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 572–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelwagen, K.; Singh, K. The role of tight junctions in mammary gland function. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2014, 19, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomo, E.; Filteau, S.M.; Tomkins, A.M.; Ndhlovu, P.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Friis, H. Subclinical mastitis among HIV-infected and uninfected Zimbabwean women participating in a multimicronutrient supplementation trial. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 97, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryeetey, R.N.; Marquis, G.S.; Brakohiapa, L.; Timms, L.; Artey, A. Subclinical mastitis may not reduce breastmilk intake during established lactation. Breastfeed. Med. 2009, 4, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.A. The clinical usefulness of breast milk sodium in the assessment of lactogenesis. Pediatrics 1994, 93, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willumsen, J.F.; Filteau, S.M.; Coutsoudis, A.; Newell, M.L.; Rollins, N.C.; Coovadia, H.M.; Tomkins, A.M. Breastmilk RNA viral load in HIV-infected South African women: Effects of subclinical mastitis and infant feeding. AIDS 2003, 17, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, M.C.; Morton, J. Physiology and endocrine changes underlying human lactogenesis II. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 3005S–3008S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, M.C.; Morton, J.; Umemura, S. Lactogenesis. The transition from pregnancy to lactation. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 48, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semba, R.D.; Kumwenda, N.; Hoover, D.R.; Taha, T.E.; Quinn, T.C.; Mtimavalye, L.; Biggar, R.J.; Broadhead, R.; Miotti, P.G.; Sokoll, L.J.; et al. Human immunodeficiency virus load in breast milk, mastitis, and mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 180, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza, C.; Johnson, C.A.; Harrist, R.; Nichols, B.L. Effects of methods of collection and storage on nutrients in human milk. Early Hum. Dev. 1982, 6, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Group A (Obstructed) n = 94 | Group B (Mixed) n = 39 | Group C (Normal) n = 102 | Group D (Donor Milk) n = 400 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, years | 35 (33–38) a | 35 (33–38) ab | 36 (34–38) a | 33 (29–38) b | <0.001 |

| GA at birth, weeks | 39 (38–39) a | 39 (38–39 )a | 39 (37–40) a | 38 (29–39) b | <0.001 |

| Infant BW, g | 2911 (2763–3258) a | 2966 (2708–3274) ab | 2968 (2763–3245) a | 2874 (904–3204) b | 0.001 |

| Infant age, months | 3 (1–5) a | 2 (1–4) a | 2 (1–3) b | 5 (3–7) c | <0.001 |

| Storage duration, days | 0 (fresh sample) a | 0 (fresh sample) a | 0 (fresh sample) a | 124 (82–150) b | <0.001 |

| Na, ppm | 810 (368–1725) a | 380 (190–550) b | 220 (140–283) c | 98 (80–130) d | <0.001 |

| K, ppm | 530 (410–663) a | 600 (500–710) a | 580 (488–710) a | 410 (360–450) b | <0.001 |

| Na/K ratio | 1.5 (0.6–3.1) a | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) b | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) c | 0.3 (0.2–0.3) d | <0.001 |

| Dependent Variable | Group Effect (F) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium (Na) | 6.049 | <0.001 |

| Potassium (K) | 19.429 | <0.001 |

| Na/K ratio | 2.157 | 0.092 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | B (SE) | 95% CI (Lower to Upper) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank Sodium (Na) | Group A vs. C | 145.56 (17.87) | 110.47 to 180.65 | <0.001 |

| Group B vs. C | 78.34 (23.25) | 32.68 to 124.01 | 0.001 | |

| Group D vs. C | −123.39 (19.24) | −161.17 to −85.61 | <0.001 | |

| Maternal age | 2.67 (1.18) | 0.36 to 4.98 | 0.024 | |

| Gestational age at birth | −1.99 (3.13) | −8.13 to 4.15 | 0.524 | |

| Infant birth weight | 0.03 (0.02) | −0.006 to 0.06 | 0.119 | |

| Infant age at milk expression | −3.96 (1.19) | −6.29 to −1.63 | <0.001 | |

| Storage duration | −0.40 (0.11) | −0.61 to −0.18 | <0.001 | |

| Rank Potassium (K) | Group A vs. C | −72.24 (22.05) | −115.53 to −28.95 | 0.001 |

| Group B vs. C | 4.01 (28.69) | −52.33 to 60.34 | 0.889 | |

| Group D vs. C | −232.37 (23.73) | −278.98 to −185.77 | <0.001 | |

| Maternal age | 1.83 (1.45) | −1.02 to 4.68 | 0.208 | |

| Gestational age at birth | 6.60 (3.86) | −0.98 to 14.18 | 0.088 | |

| Infant birth weight | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.05 to 0.03 | 0.753 | |

| Infant age at milk expression | −3.94 (1.47) | −6.82 to −1.07 | 0.007 | |

| Storage duration | 0.23 (0.14) | −0.04 to 0.49 | 0.095 | |

| Rank Na/K ratio | Group A vs. C | 189.45 (20.96) | 148.28 to 230.61 | <0.001 |

| Group B vs. C | 95.61 (27.28) | 42.05 to 149.17 | <0.001 | |

| Group D vs. C | −7.27 (22.57) | −51.59 to 37.04 | 0.747 | |

| Maternal age | 2.12 (1.38) | −0.59 to 4.83 | 0.125 | |

| Gestational age at birth | −6.09 (3.67) | −13.30 to 1.11 | 0.097 | |

| Infant birth weight | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.002 to 0.07 | 0.066 | |

| Infant age at milk expression | −2.24 (1.39) | −4.98 to 0.50 | 0.109 | |

| Storage duration | −0.71 (0.13) | −0.97 to −0.46 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsieh, P.-Y.; Tanaka, M.; Himi, T.; Mizuno, K. Human Milk Electrolytes as Nutritional Biomarkers of Mammary Gland Integrity: A Study Across Ductal Conditions and Donor Milk. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203283

Hsieh P-Y, Tanaka M, Himi T, Mizuno K. Human Milk Electrolytes as Nutritional Biomarkers of Mammary Gland Integrity: A Study Across Ductal Conditions and Donor Milk. Nutrients. 2025; 17(20):3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203283

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsieh, Po-Yu, Miori Tanaka, Tomoko Himi, and Katsumi Mizuno. 2025. "Human Milk Electrolytes as Nutritional Biomarkers of Mammary Gland Integrity: A Study Across Ductal Conditions and Donor Milk" Nutrients 17, no. 20: 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203283

APA StyleHsieh, P.-Y., Tanaka, M., Himi, T., & Mizuno, K. (2025). Human Milk Electrolytes as Nutritional Biomarkers of Mammary Gland Integrity: A Study Across Ductal Conditions and Donor Milk. Nutrients, 17(20), 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203283